Abstract

In response to the expressed need for more sophisticated and multidisciplinary data concerning ageing of the Australian population, the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ALSA) was established some two decades ago in Adelaide, South Australia. At Baseline in 1992, 2087 participants living in the community or in residential care (ranging in age from 65 to 103 years) were interviewed in their place of residence (1031 or 49% women), including 565 couples. By 2013, 12 Waves had been completed; both face-to-face and telephone personal interviews were conducted. Data collected included self-reports of demographic details, health, depression, morbid conditions, hospitalization, gross mobility, physical performance, activities of daily living, lifestyle activities, social resources, exercise, education and income. Objective performance data for physical and cognitive function were also collected. The ALSA data are held at the Flinders Centre for Ageing Studies, Flinders University. Procedures for data access, information on collaborations, publications and other details can be found at [http://flinders.edu.au/sabs/fcas/].

Key Messages

The population-based ALSA is one of the longest-running cohort studies of older people in the world. The frequency of data collection, spanning some 12 waves over 22 years, has allowed insights about ageing rarely possible from other longitudinal studies of ageing.

While the majority of participants at every wave appear to be experiencing ageing as a positive process, with preservation of cognitive, affective and functional health, wide interindividual differences, including in intra-individual change, were also observed.

Many of the identified factors that promote longevity and quality of life are aspects of lifestyle that are amenable to change. Early screening could identify risk factors. Intervention strategies that encourage regular exercise, support social networks and engender a positive state of mind may help promote survival and a good quality of life.

A loyal participant “Sheila” is shown on three occasions over her 21 years of continuous involvement in the ALSA. She was 80 years of age at Wave 3, shown doing the Clinical Assessment; 95 at Wave 11 doing her home interview and 99 years at Wave 12. In 2014 she celebrated her 100th birthday.

Why was the ALSA cohort set up?

The proportion of Australians over 65 years old is projected to increase from 14% in 2012 to 27.1% by 2101, with South Australia having the second oldest population in Australia.1

In response to the need for more sophisticated data concerning ageing of the Australian population, the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ALSA) was established two decades ago in Adelaide, capital of South Australia. The ALSA is multidisciplinary and designed to improve understanding of how a broad range of individual and structural factors are associated with age-related changes in health and well-being. Following an extensive pilot study2 in 1988, ALSA Wave 1 (Baseline) commenced in 1992.

Needs for comprehensive information on ageing still exist, and a strength of the study is that the surviving ALSA cohort are now aged 85 years or older: the most rapidly growing portion of the older population.

What does ALSA cover?

The overarching aim was to investigate how social, biomedical, behavioural, economic, and environmental factors affect ageing. Specific objectives of ALSA were to:

determine health and functional status and track changes in these characteristics over time;

identify risk factors for major chronic conditions and normative age-related changes;

assess effects of disease processes and lifestyle choices on functional status, and the demand for acute and longer-term aged care services; and

examine mortality outcomes.

Who is in the cohort?

The ALSA is a population-based cohort of older men and women who resided in the Adelaide Statistical Division and were aged 70 years or more on 31 December 1992. Both community-dwelling and people living in residential care were eligible and were randomly selected from the South Australian Electoral Roll. The primary sample was stratified by age groups (70-74, 75-79, 80-84 and 85 years or more), gender and local government area.

Letters of introduction and invitation were sent to 3263 people; 560 were not eligible (210 were deceased, 88 had no translator available, 189 could not be contacted at the address, 37 were out of the geographical scope and 36 were ineligible for other reasons, e.g. for incorrect date of birth). Of the 2703 eligible persons, 1477 consented and completed an interview (response fraction: 54.6%).

In addition to the primary sample, spouses and other household members of eligible persons were invited to take part. The age requirement for spouses was relaxed to age 65 years. An additional 597 spouses and 13 household members were recruited. In total, 2087 people took part in a Wave 1 interview, including 565 couples. Key Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of the ALSA participants at Baseline

| Characteristics | Summary |

|---|---|

| Gender, n = 2087 (%) | |

| Male | 1056 (51) |

| Female | 1031 (49) |

| Age (mean years, SD) | 78.3 (6.7) |

| Age in 5-year bands, n = 2087 (%) | |

| 65–69 | 140 (7) |

| 70–74 | 562 (27) |

| 75–79 | 524 (25) |

| 80–84 | 429 (21) |

| ≥85 | 432 (21) |

| Marital status, n = 2086 (%) | |

| Married/de facto | 1367 (65.0) |

| Widowed | 594 (28.6) |

| Never married | 76 (3.6) |

| Divorced/separated | 49 (2.4) |

| Self-rated health, n = 2081 (%) | |

| Excellent / very good, | 790 (38) |

| Good | 633 (30.4) |

| Fair/poor | 658 (31.6) |

| Education: age left school, n = 2061 (%) | |

| ≤14 years | 1155 (55.3) |

| >15 years | 906 (43.4) |

| Annual income, n = 1930 (%) | |

| $AUD <$12,000 | 686 (35.5) |

| $AUD $12,000-<$30,000 | 1083 (56.1) |

| $AUD $30,000-<$50,000 | 136 (7.1) |

| $AUD ≥$50,000 | 25 (1.3) |

After consenting, arrangements were made for the structured personal interview to be conducted at the participant's usual place of residence. Then participants were invited to take part in a detailed clinical assessment and complete self-administered questionnaires. To minimize participant attrition, at each wave members of the cohort were asked to provide contact details of three people who could provide information about their whereabouts should their residential location change.

Birthday and Christmas cards, and periodic newsletters, were sent to participants between waves. To assess the representativeness of the Baseline sample, we compared them on a range of health-related markers to the overall over-70 population in South Australia.3 Weights were applied to the data to adjust for age and sex stratification, and the probability of selection of respondents within each local government area sampled. The percentages for the weighted and unweighted values showed high correspondence on activities of daily living, self-ratings of health, number of health professionals consulted and hospital stays in the previous year. At Baseline, 14% of participants used formal services, comparing favourably to 12% of the over-70 population.

Attrition was examined at Wave 3 in relation to partaking in the clinical assessment.4 Those who did not complete the clinical assessment at Wave 3 had had poorer health and cognitive function at Wave 1, independently of age and gender. Rates of possible dementia were also higher in participants who did not undertake Wave 3 clinical assessment, compared with both those who did so and population data. Possible sample selectivity was also assessed by Luszcz et al.5 using Baseline data to explain age-related differences in memory. We compared the target community-dwelling sample who met inclusion criteria with all community-dwellers who completed the structured interview. Table 2 shows a high degree of similarity between the groups; differences were in all cases a small fraction of the standard deviation. The target sample was slightly younger, healthier and more cognitively able.

Table 2.

Summary of target sample characteristics and differences compared with full sample residing in community

| Sub-sample |

Differencea |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % | M | SD | % | M |

| Age | 77.6 | 5.5 | −0.65 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 54.2 | 515 | +0.1 | ||

| Female | 45.8 | 436 | −0.1 | ||

| Married | 70 | +3.5 | |||

| School (left ≥16 years) | 29 | +4.2 | |||

| Illnesses | 5.5 | 2.8 | −0.18 | ||

| Medications | 2.6 | 1.9 | +0.02 | ||

| Self-rated health (≥good) | 74 | +5.0 | |||

| Activities of daily living (≥1) | 11 | −5.0 | |||

| Instrumental activities of | |||||

| daily living (≥1) | 32 | −3.0 | |||

| Depressive symptoms | 7.4 | 6.7 | −0.53 | ||

| Adelaide Activities Profileb | |||||

| Home maintenance | 52.5 | 18.7 | +2.5 | ||

| Domestic | 52.2 | 18.5 | +2.2 | ||

| Social | 51.3 | 19.8 | +1.3 | ||

| Service to others | 52.3 | 20.3 | +2.3 | ||

| NART errors | 22.2 | 8.4 | −0.27 | ||

| IQ estimatec | 102.0 | 9.5 | +0.32 | ||

| Processing accuracy | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.00 | ||

| Processing speed | 29.9 | 10.9 | +0.68 | ||

| Picture naming | 13.7 | 1.6 | +0.18 | ||

| Recall | |||||

| Address | 8.60 | 1.6 | +0.20 | ||

| Symbol | 6.28 | 2.0 | +0.06 | ||

| Picture | 5.62 | 2.3 | +0.17 | ||

More generally, missing data resulting from attrition have been analysed using maximum likelihood estimation, e.g. growth curve modelling,6 which produces estimates based on all available data under missing-at-random assumptions.7

How often have they been followed up?

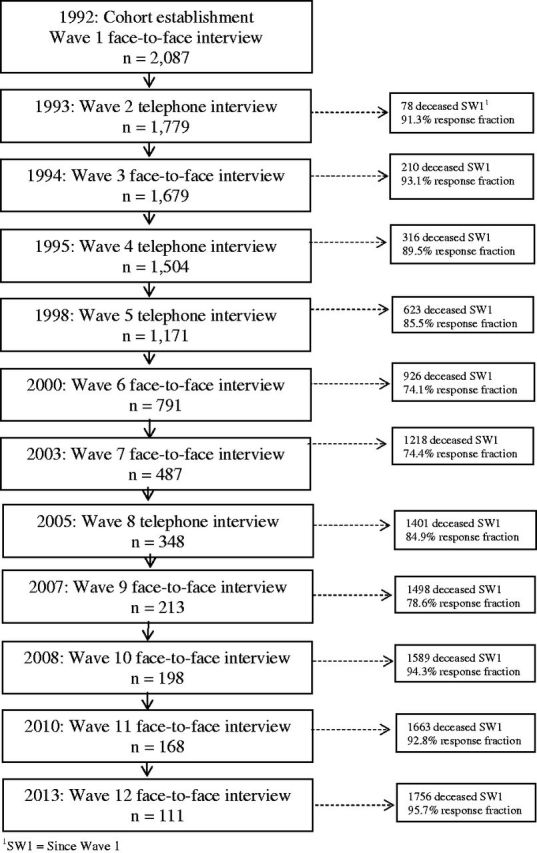

There have been 12 waves of data collection. Wave 1 took place from September 1992 to March 1993. The next three waves took place 1, 2 or 3 years thereafter. Subsequent waves were approximately 6, 8, 11, 13, 15, 16, 18 and 21 years after baseline, with funding secured for a 22-year follow-up. Unequal intervals reflect funding availability for follow-up.

There were two key modalities of data collection: in person and by telephone. Waves 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 11 and 12 involved multiple components including structured interviews, clinical assessment (each of these components took 1.5-2 hours/hrs), and self-administered questionnaires (an additional 30-60 min). Waves 2, 4, 5 and 8 were shorter telephone interviews that focused on major life events since the previous wave. To accommodate increasing sensory frailty of the surviving participants, Wave 10 was conducted in person.

Figure 1 presents a schema of timing and response fractions.

Figure 1.

Mode of interview and number of participants over time in the ALSA study. SW11, since Wave 1.

What has been measured?

Measures included in each wave are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of ALSA domains, Waves 1 through 12

| Study wave |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QUESTIONNAIRE DOMAINS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Residence and household structure | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Socio-demographic information | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Family composition | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Health status of spouse | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Carer role | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Self-rated health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Depression | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Chronic conditions and symptoms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Medications | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Falls/injuries | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fractures/surgery | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hearing and vision | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Continence | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Health service utilization | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Dental health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Quality of life | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Weight history | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Personal growth | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Purpose in life | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Reproductive history (females) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Cognitive status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Sleep | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Memory Impairment Screen/Executive Function | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| ADL Physical Performance and Physical Aids | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| IADL Physical Performance and Physical Aids | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gross mobility | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Social support and interaction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| General life satisfaction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Significant life events | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Tobacco and alcohol consumption | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Exercise and activity levels | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Social activities and religion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Adelaide Activities Profile | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Driving | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CLINICAL ASSESSMENT DOMAINS | ||||||||||||

| Boston Naming Task | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Digit Symbol Subtest (of the WAIS-R) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Digit Symbol Recall | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| National Adult Reading Test (NART) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Initial Letter Fluency Task (FAS) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Flinders Fluency Task | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Uses for Common Objects | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Quality of Life (Hopes and Fears for the Future) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Audiometry | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Visual acuity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Sitting, standing blood pressure | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Weight and height | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Girths | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Skinfold thickness | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Lower leg length | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Arm span (demispan) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Functional reach | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Grip strength | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Physical signs, ecchymoses, pitting oedema | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Physical performance evaluation (EPESE) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Abnormalities of gait and posture | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| SELF-COMPLETE QUESTIONNAIRES DOMAINS | ||||||||||||

| Nutrition: You and Your Diet (2 versions) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Nutrition | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Dental: Oral Health Impact Profile | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Psychological: attitudes and views (control, morale, self-esteem, metamemory)a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Emotional Health Questionnaire | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Sexual activity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| ANCILLARY CLINICAL STUDIES DOMAINS | ||||||||||||

| Bone densitometry | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Nerve conduction studies | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Spirometry | ✓ | |||||||||||

| LABORATORY STUDIES DOMAINS | ||||||||||||

| Haematology: fasting blood | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Biochemistry: fasting blood | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Blood sample: blotted onto FTA GeneCard | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

EPESE, Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies for the Elderly (USA); WAIS-R, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

aSome of these instruments appeared in the household interview at later waves.

Structured interviews

The interview content was informed by other international longitudinal studies of ageing.8–14 Domains included demographic details, health, depression, morbid conditions, hospitalization, cognition, gross mobility and physical performance, activities of daily living, lifestyle activities, social factors, exercise, education and income.

Clinical assessments

These assessments objectively measured physical and cognitive functioning. The physical examination included blood pressure, anthropometry, visual acuity, audiometry, grip strength, balance and gait. The cognitive assessment included memory, information processing efficiency, verbal ability and executive function. All clinical assessments were conducted by graduates trained in standard administration.

Self-administered questionnaires

Self-administered questionnaires, to be mailed back to the study co-ordinating centre or collected at the clinical assessment, encompassed nutrition, dental health, sexual activity and psychological measures of self-esteem, morale, control beliefs and metamemory.

Biochemical analysis

Fasting blood samples (Waves 1, 3 and 9) and urine specimens (Wave 1) were collected on the morning following the clinical assessment. Basic haematology measures, 20-channel biochemical analysis and lipid profiles have been conducted for blood, and standard assays for the urine samples. At Wave 1, selected hormone assays were carried out.

Qualitative interviews

The study incorporated qualitative sub-studies, on sleep15 and widowhood.16 In 2013 qualitative interviews were conducted with 20 Wave 12 participants aged 90 and older, to gain a unique perspective on lived experiences that may be indicative of resilient ageing.

Data linkage

Information about use of community services in the preceding year was collected at Wave 1 from participants’ personal physicians and three community nursing and personal care services. Supplementary administrative data spanning Waves 6 through 8 were gathered from the Australian Health Insurance Commission (HIC), the federal government entity that manages and delivers publicly funded medical and pharmaceutical services. HIC data captured the use, nature, timing, charge and benefit paid for medical services and included prescriptions funded through the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Deaths have been monitored systematically each year through the state-based Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages and from relatives or other informants on deaths between reports. If participants could not be located, informants were contacted and they supplied date of death if a participant died outside of South Australia.17 At January 2014, 1806 (86%) of the original participants had died.

What has the ALSA found? Key findings and publications

As of 31 December 2013, 114 peer-reviewed papers, 1 book, and 6 book chapters have been published, with a listing available at the ALSA website [http://www.flinders.edu.au/sabs/fcas/alsa/bibliography.cfm]. The range of publication outlets encompasses biomedicine, epidemiology, gerontology and psychology, highlighting the interdisciplinary nature of the findings.

Successful ageing

Using MacArthur criteria developed in the USA18, Andrews et al.19 identified three distinct groups of ALSA participants who were ageing with varying degrees of success at Baseline. Groups were compared on functioning across a range of psychological, physical and social domains, and mortality. Results showed risk and protective effects for successful ageing from physical functioning and performance, lifestyle, cognition, affect and personality. Eight-year mortality was highest in the group ageing with least success. Baseline interindividual differences showed that those ageing most successfully not only live longer, but also experience a better quality of life.

Psychological functioning

Seeking to understand factors, other than age, that contribute to cognitive functioning has been a major focus of our work.5 We examined the common cause hypothesis of cognitive ageing, according to which decline in cognition and sensory functioning go hand in hand, due to shared neurophysiological underpinnings associated with brain ageing. Unlike initial work showing a strong relationship between cognitive and sensory (hearing and vision) functioning,20 we found evidence for both specific and common factors underlying changes in them.21 This was confirmed in a study showing that neither processing efficiency nor sensory abilities entirely explained cognitive change over the first 8 years in the ALSA.22 Relatedly, we examined de-differentiation of cognitive functions with ageing,23 with results suggesting that common factors play a smaller role than previously thought in explaining age-related changes in cognitive and sensory performance.24

We have used some of the cognitive data, e.g. the naming of simple line drawings25 and the National Adult Reading Test,26 to provide norms against which cognitive performance can be compared to distinguish individuals’ normal patterns of cognitive ageing from those with possible cognitive impairment. The contribution of cognitive functioning to health and functional outcomes has also been demonstrated in, for example, studies of mortality,17 driving cessation27 and self-esteem.6

The Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE28) was included in all major ALSA waves. Graham et al.29 used Bayesian hierarchical modelling with a joint tobit distribution to examine serial measurements of MMSE and informative dropout or death. Results suggested that higher levels of physical activity, more education and higher income were associated with higher MMSE at baseline, and a slower rate of decline.

Other psychological research has considered aspects of affective functioning, encompassing mood and emotional well-being, and subjective perceptions of ageing. A particular focus has been on depressive symptoms, as outcomes, mediators or explanatory variables. We have provided prevalence figures for depression in both community-dwellers (14%) and persons living in residential aged care (32%).30 Extending our work concerning falls,31,32 depressive symptoms, along with cognitive functioning, are linked to driving cessation.27,33 Following driving cessation, the stronger an individual's perceived control, the less likely they are to experience depressive symptoms.33 Another investigation34 showed that depressive symptoms predict declining cognitive processing, rather than the converse.

A recent study6 examined trajectories of change in self-esteem over chronological age and time-to-death, indicating remarkable stability until very late in life when minor declines emerged. Poorer perceived control was associated with poorer self-esteem, as was poorer cognition, which also related to steeper age-related and mortality-related declines. Another psychological construct, self-perceptions of one's own ageing, appears to play a powerful role in predicting health35 and survival.36 It is plausible that those with better perceptions of ageing are more likely to engage in positive health behaviours.

Physical functioning

The average number of chronic health conditions at Wave 1 was 5.3 [standard deviation (SD) = 3.0], with 6% reporting ≥10. The majority of older adults have multiple chronic conditions (64% had ≥2 chronic conditions, 40% reporting ≥337). Arthritis was the most common condition experienced in conjunction with another condition: arthritis and cardiovascular disease (21%), hypertension (19%), gastrointestinal disease (18%) and mental health problems (17%) were most prevalent. Over a 14-year period, participants with 3 or 4 chronic conditions at Wave 1 had a 25% increased risk of mortality compared with those with no chronic disease, whereas those with ≥5 chronic diseases had an 80% increased risk of mortality, after adjusting for age, sex and place of residence.38

Physical functioning has been variously considered as both an exposure and outcome in analyses using ALSA data. Sargent-Cox et al.39 established that self-perceptions of ageing predicted 16-year change in physical functioning over lags of 1 year. However, the converse did not hold: changes in physical functioning did not predict changes in self-perceptions of ageing. A range of studies has also examined vision and hearing.40,41

Social functioning

Different aspects of ALSA participants’ social milieu have been demonstrated to contribute across a range of health and well-being outcomes. Larger overall social networks were associated with reduced residential care admission, risk of disability and 10-year mortality,42–44 as well as memory decline.45 Specifically, larger friends’ social networks were of benefit for survival across a decade43 and for memory preservation across 15 years.45

After widowhood, trajectories of social engagement across 15 years increased, and frequency of phone contact with children and participation in social activities were higher for widowed than for married ALSA participants.16 Baseline data showed that informal and formal social support jointly buffered the effects of disability on depressive symptoms in later life.

Couples in Alsa

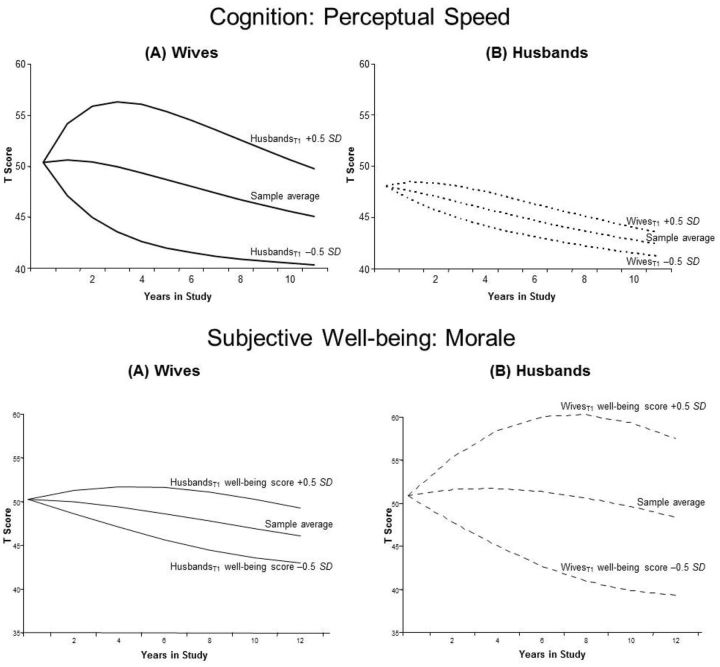

A distinguishing feature of ALSA is the inclusion of couples. We have examined the dynamic relationships between spouses over time in cognition and in subjective well-being. Figure 2 shows spousal interdependencies in trajectories of cognition and well-being. Spousal interrelations in level and change of cognitive functioning across 11 years showed that perceptual speed, a robust marker of cognitive functioning, of husbands predicted subsequent perceptual speed decline for wives (time lags of 1 year),47 but the opposite unidirectional effect (i.e. wives scores predicting husbands’ decline) did not hold. In analyses of subjective well-being (morale) across 11 years, wives’ changes in morale were shown to predict subsequent changes among husbands, but not the reverse. Husbands whose wives reported higher initial subjective well-being showed a relatively shallower decline over time relative to husbands whose wives reported lower initial subjective well-being, which had little effect on husbands.48

Figure 2.

Illustration of the differential magnitude of dynamic partner effects between wives’ and husbands’ perceptual speed47 (Top Panel) and subjective well-being48 (Bottom Panel) Top Panel A represents model-implied sample (of average age and education) means on wives’ cognition (perceptual speed) from a bivariate Dual Change Score Model (Full Dynamics) for the hypothetical case that the initial sample means for husbands’ cognition were varied by half a standard deviation (i.e., 5 T-score units). Under the assumption of comparable wives’ cognition at T1, wives with cognitively fit husbands (husbandsT1 +0.5 SD) showed relatively shallow perceptual speed decline, whereas those with cognitively less fit husbands (husbandsT1 –0.5 SD) showed relatively steeper perceptual speed decline. In contrast, the lines in Top Panel B indicate that husbands’ cognitive trajectories of change over time were minimally changed as a function of different initial levels of wives’ perceptual speed. Bottom Panel B shows model-implied change in subjective well-being (SWB: morale) for participants (of average age and education, adjusted also for health constraints, length of marriage, and number of children) assuming that all husbands reported similar morale at T1, but their wives differed in initial morale. On average, morale declined for husbands; but husbands whose wives reported low SWB (wivesT1 –0.5 SD) showed relatively stronger SWB decline, whereas those husbands whose wives reported high SWB (husbandsT1 +0.5 SD) showed relatively shallow decline. In contrast, Bottom Panel A shows wives’ decline was altered modestly as a result of varying initial husbands’ SWB.

Adopting a different approach, the interdependence of spousal social activity trajectories over the same span was examined. Joint spousal activities depend not only on individual resources, but also on spousal cognitive, physical and affective resources at baseline.49 Wives performed more social activities and displayed different associations between depression and social activity than did husbands. Stronger within-couple associations were more evident in social activities than in cognition. Together, these studies suggest that the impact of one spouse on the other varies depending on the domain of inquiry.

What are the main strengths and weaknesses of the study?

The main strengths of ALSA are the population-based sample, frequent data collections and the duration of the study. ALSA was unprecedented in the southern hemisphere at the time of its establishment. There has been a low rate of experimental attrition across the two decades of follow-up. The range and multidisciplinary nature of the domains included in the ALSA means that it has been pivotal in informing practice and policy on healthy ageing and establishing collaborations.50 Using measures common to international studies (e.g.10,11) has assisted in undertaking comparative studies.

The main limitations pertain to the varying intervals between data collection and the use of a single panel, with no replenishment. Attrition from wave to wave contributes to positive selection effects inherent in most longitudinal studies of older adults. The breadth of the study, although an overall strength, also means that interrogation in many areas is somewhat limited. Financial constraints and vagaries of the availability of external funding dictated the frequency of study occasions and prohibited inclusion of non-English speakers in the sample.

Can I get hold of the data? Where can I find out more?

Enquiries regarding the use of collected data are welcome. All proposals for specific analyses are reviewed by a scientific committee. The ALSA data are held at the Flinders Centre for Ageing Studies, Flinders University. Procedures for data access, information on collaborations and other details can be found at [http://flinders.edu.au/sabs/fcas/].

Acknowledgements

All of the participants and the ALSA team of collaborators, research assistants, graduate and postgraduate students are thanked for their involvement in the project. The late Gary Andrews and the late George Myers began the study, and the late Michael Clark was one of the founding study chief investigators. They helped to build a dedicated team of researchers, in addition to the authors. We wish to acknowledge the ongoing commitment and involvement at various points during the project of Lynne Cobiac, Debbie Faulkner, Denis Gerstorf, Andy Gilbert, James Harrison, Christiane Hoppmann, Konrad Pseudovs and Linnett Sanchez.

Funding

The first four ALSA waves were funded by the US National Institute on Aging (AG 08523-02). Other funding sources have included the Australian Research Council (DP0879152 and DP130100428; LP 0669272; LP 100200413; Future Fellowship FT100100228 to T.D.W.) and the National Health and Medical Research Council (Project Grants 179839; 229922; Early Career Fellowships 987100 to K.J.A. and 627033 to L.C.G.).

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population Projections, Australia, 2012 (Base) to 2101, catalogue no. 3222.0 .Canberra, ACT: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andrews G, Cheok F, Carr S. The Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Aust J Ageing 1989;8:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mawby L, Clark MS, Kalucy ER, Hobbin ER, Andrews GR. Determinants of formal service use in an aged population. Aust J Age 1996;15:177–81. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA. Selective non-response to clinical assessment in the longitudinal study of ageing: Implications for estimating population levels of cognitive function and dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;17:704–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luszcz M, Bryan J, Kent P. Predicting episodic memory performance of very old men and women: Contributions from age, depression, activity, cognitive ability and speed. Psychol Aging 1997;12:340–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wagner J, Gerstorf D, Hoppmann C, Luszcz MA. The nature and correlates of self-esteem trajectories in late life. J Pers Social Psychol 2013;105:139–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Little T, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. New York: Wiley, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Palmore E. Normal Ageing: Reports From the Duke Longitudinal Study, 1955-1969. Durham, NC; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palmore E. Normal ageing II: Reports from the Duke Longitudinal Study, 1955-1969. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Institute on Aging. Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly Resource Data Book. Washington, DC: National Institute of Health, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Center for Health Statistics (HCHS). The Supplement on Aging to the 1984 National Health Interview Survey Vital and Health Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Center for Health Statistics. A Description of NHANES III. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Svanborg A. Seventy-year-old people in Gothenburg: A population study in an industrialized Swedish city, general presentation of social and medical conditions. Acta Med Scand Suppl 1977;611:5–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Svanborg A. The health of the elderly population: Results from longitudinal studies with age-cohort comparisons. Ciba Found Symp 1988;134:3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walker RB, Luszcz MA, Hislop J, Moore V. A gendered life course examination of sleep difficulties among older women. Ageing Soc 2012;32:219–38. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Isherwood L, King D, Luszcz MA. A longitudinal analysis of social engagement in late-life widowhood. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2012;74:211–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA, Giles LC, Andrews GR. Demographic, health, cognitive, and sensory variables as predictors of mortality in very old adults. Psychol Aging 2001;16:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berkman LF, Seeman TE, Albert M, et al. High, usual and impaired functioning in community-dwelling older men and women: Findings from the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Aging. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andrews GR, Clark MS, Luszcz MA. Successful ageing in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing: Applying the MacArthur Model cross-nationally. J Soc Issues 2002;58:749–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindenberger U, Baltes PB. Sensory functioning and intelligence in old age: A strong connection. Psychol Aging 1994;9:339–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA, Sanchez L. Two-year decline in vision but not hearing is associated with memory decline in very old adults in a population based sample. Gerontol 2001;47:289–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anstey KJ, Hofer SM, Luszcz MA. A latent growth curve analysis of late-life sensory and cognitive function over 8 years: Evidence for specific and common factors underlying change. Psychol Aging 2003;18:714–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Balinsky B. An analysis of the mental factors of various age groups from nine to sixty. Genetic Psychol Monogr 1941;23:191–234. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Anstey KJ, Hofer SM, Luszcz MA. Cross-sectional and longitudinal patterns of dedifferentiation in late-life cognitive and sensory function: The effects of age, ability, attrition, and occasion of measurement. J Exp Psychol: General 2003;132:470–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kent PS, Luszcz MA. A review of the Boston Naming Test and Multiple-Occasion Normative Data for older adults on 15-item versions. Clin Neuropsychol 2002;16:555–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kiely KM, Luszcz MA, Piguet O, Christensen H, Bennett H, Anstey KJ. Functional equivalence of the National Adult Reading Test (NART) and Schonell reading tests and NART norms in the Dynamic Analyses to Optimise Ageing (DYNOPTA) project. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2011;33:410–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anstey KJ, Windsor TD, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR. Predicting driving cessation over 5 years in very old adults: Psychological wellbeing and cognitive competence are stronger predictors than physical health. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:121–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Graham PL, Ryan LM, Luszcz MA. Joint modelling of survival and cognitive decline in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat 2011;60:221–38. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Sargent-Cox K, Luszcz MA. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in a longitudinal, population-based study including individuals in the community and residential care. Am J Geriatr Psych 2007;15:497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Anstey KJ, Burns R, von Sanden C, Luszcz MA. Psychological well-being is an independent predictor of falling in an 8-year follow-up of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2008;63B:249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Luszcz MA. An 8-year prospective study of the relationship between cognitive performance and falling in very old adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Windsor TD, Anstey KJ, Butterworth P, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR. The role of perceived control in explaining depressive symptoms associated with driving cessation in a longitudinal study. Gerontologist 2007;47:215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bielak AAM, Gerstorf D, Kiely KM, Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA. Depressive symptoms predict decline in perceptual speed in older adulthood. Psychol Aging 2011;26:576–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sargent-Cox KA, Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA. Change in health and self-perceptions of ageing over 16 years: the role of psychological resource. Health Psychol 2012;31:423–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sargent-Cox KA, Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA. Longitudinal change of self-perceptions of ageing and mortality. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2014;69:168–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Caughey GE, Ramsay EN, Vitry AI, et al. Comorbid chronic diseases, discordant impact on mortality in the elderly: A 14 year longitudinal population study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;57:180–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gilbert AL, Caughey GE, Vitry AI, et al. Ageing well: improving the management of patients with multiple chronic health problems. Aust J Ageing 2011;30:32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sargent-Cox KA, Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA. The relationship between change in self-perceptions of ageing and physical functioning in older adults. Psychol Aging 2012;27:750–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kiely KM, Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA. Dual sensory loss and depressive symptoms: The importance of hearing, daily functioning and activity engagement. Front Hum Neurosci 2013;7:837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kiely KM, Gopinath B, Mitchell P, Luszcz MA, Anstey KJ. Cognitive, health, and sociodemographic predictors of longitudinal decline in hearing acuity among older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012;67:997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Giles LC, Glonek GFV, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR. Do social networks affect the use of residential aged care among older Australians? BMC Geriatr 2007;7:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Giles LC, Glonek GFV, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR. Effect of social networks on 10 year survival in very old Australians: The Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005, 2005;59:574–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Giles LC, Metcalf PA, Glonek GFV, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR. The effects of social networks on disability in older Australians. J Aging Health 2004;16:517–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Giles LC, Anstey KJ, Walker RB, Luszcz MA. Social networks and memory over 15 years of followup in a cohort of older Australians: Results from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Ageing Res 2012;2012:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chan N, Anstey KJ, Windsor T, Luszcz MA. Disability and depressive symptoms in later life: the stress-buffering role of informal and formal support. Gerontology 2011;57:180–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gerstorf D, Hoppmann CA, Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA. Dynamic links of cognitive functioning among married couples: Longitudinal evidence from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychol Aging 2009;24:296–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Walker RA, Luszcz MA, Gerstorf D, Hoppmann CA. Subjective well-being dynamics in couples from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Gerontology 2011;57:153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hoppmann CA, Gerstorf D, Luszcz M. Spousal social activity trajectories in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing in the context of cognitive, physical, and affective resources. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2008;63:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Luszcz M, Giles L, Eckermann S, et al. The Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing: 15 Years ofAageing in South Australia: Adelaide, SA: South Australian Department of Families and Communities, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Clark MS, Bond MJ. The Adelaide Activities Profile: A measure of the lifestyle activities of elderly people. Aging: Clin Exp Res 1995;7:174–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]