Abstract

Background: Multimorbidity is a major driver of physical and cognitive impairment, but rates of decline are also related to ageing. We sought to determine trajectories of decline in a large cohort by disease status, and examined their correspondence with biomarkers of ageing processes including growth hormone, sex steroid, inflammation, visceral adiposity and kidney function pathways.

Methods: We have followed the 5888 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) for healthy ageing and longevity since 1989–90. Gait speed, grip strength, modified mini-mental status examination (3MSE) and the digit symbol substitution test (DSST) were assessed annually to 1998–99 and again in 2005–06. Insulin-like growth hormone (IGF-1), dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS), interleukin-6 (IL-6), adiponectin and cystatin-C were assessed 3–5 times from stored samples. Health status was updated annually and dichotomized as healthy vs not healthy. Trajectories for each function measure and biomarker were estimated using generalized estimating equations as a function of age and health status using standardized values.

Results: Trajectories of functional decline showed strong age acceleration late in life in healthy older men and women as well as in chronically ill older adults. Adiponectin, IL-6 and cystatin-C tracked with functional decline in all domains; cystatin-C was consistently associated with functional declines independent of other biomarkers. DHEAS was independently associated with grip strength and IL-6 with grip strength and gait speed trajectories.

Conclusions: Functional decline in late life appears to mark a fundamental ageing process in that it occurred and was accelerated in late life regardless of health status. Cystatin C was most consistently associated with these functional declines.

Keywords: Ageing, disability, gait speed, grip strength, cognitive function, biomarkers

Key messages

Trajectories of functional decline show strong age acceleration late in life in healthy as well as chronically ill older adults.

Grip strength appears to decline earlier than gait, 3MSE or DSST.

IL-6, adiponectin and especially cystatin-C track with functional decline.

Introduction

In clinical and population research, functional impairment is often used as a summary measure of the ageing process because of its face validity and clinical relevance.1–4 Function is strongly related to chronological age and is also influenced by the accumulated effects of many common and often comorbid age-related chronic conditions.5,6 Poor function strongly predicts subsequent disability and mortality.7 Some studies have characterized function into late life with self-report,8 but few have conducted repeated measures of performance over many years in a single cohort into very old age. Risk factors for accelerated decline have been examined9–11 and patterns of recovery have been demonstrated12,13 based on single measures of physical or cognitive function or self-report of disability in old age.

Although several blood-derived biomarkers have been examined as risk factors for functional decline, longitudinal trajectories have not been well characterized with regard to health and function. This provides an incomplete description of the multifactorial and longitudinal process that is ageing. A close correspondence between biomarkers and function would suggest that the biomarkers might be considered as potential targets or intermediate markers to track response to therapeutics designed to modify the ageing process. We selected biomarkers representing key biological ageing processes including growth hormone, sex steroids, inflammation, visceral adiposity and kidney ageing. IGF-1 reflects growth hormone action and declines with age. When deficient in animal models, IGF-1 is associated with longer life.14 However, in older humans, lower levels have been associated with mortality.15 DHEAS is an adrenal androgen and the major source of estrogen in women and testosterone in men later in life and thus reflects sex steroid function. It also declines with age16,17 and its association with mortality may be non-linear.18 IL-6 is a marker of dysregulated inflammatory response. Levels increase with age as well as with obesity and with smoking and strongly predict mortality.19,20 Adiponectin was assessed originally as a measure of low visceral fat. Although it exhibits anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing properties, it has been documented to increase with age and to predict mortality in late life and may be important to muscle function.21 Cystatin–-C is a novel marker of ageing of the kidney. It increases with age and age-related loss of the glomeruli22,23 which can drive other risk factors.24 Few studies of biomarkers have assessed multiple markers in the same cohort and none have measured all of these over time.

In this report, we sought to identify trajectories of both physical and cognitive functions that could characterize relatively healthy ageing into advanced old age. Further, we sought to determine how risk factors for functional decline track with function over time. We describe trajectories of grip strength, gait speed, the modified mini-mental status examination (3MSE) and the digit symbol substitution test (DSST) by age and chronic disease status over time in a cohort with repeated measures for up to 18 years. We hypothesized that trajectories of physical and cognitive decline would be attenuated in older adults without major chronic disease compared with those with or developing disease. We also examined the individual as well as the joint associations of changes in IGF-1, DHEAS, IL-6, adiponectin and cystatin-C with functional decline, hypothesizing that some of these biomarker trajectories would track more closely with functional decline than others.

Methods

Cohort

The CHS All Stars Study follows participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) for healthy ageing and longevity. The original CHS study was established in 1989–90 as a cohort study of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease in 5201 men and women from four US communities enrolled from a random selection of Medicare enrollees and age-eligible household members.25,26 In 1992–93, 687 African American men and women were enrolled with a baseline examination comparable to the 1989–90 examination for a total of 5888 participants. Participants were seen annually for a clinic visit and interviewed 6 months later by telephone through 1999. Thereafter, telephone interviews were conducted every 6 months to the present time. Additionally, the CHS All Stars Study offered a clinic or home visit to surviving participants in 2005–06 in order to re-assess physical and cognitive function.5 The current analysis includes 5846 participants, with 42 excluded for lack of any biomarker or function data.

Definition of healthy

Healthy was defined at each visit as free of any of the following major chronic illnesses. Once any of these diseases was identified for a participant, that participant was assumed to have the chronic illness throughout the rest of follow-up.29

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was defined as coronary heart disease (CHD) [angina, myocardial infarction (MI), bypass surgery or angioplasty], claudication, congestive heart failure (CHF), stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA). CVD events were confirmed at baseline and adjudicated during follow-up.27,28

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was defined by self-report of a current diagnosis of asthma, emphysema or chronic bronchitis confirmed by a doctor at baseline and by hospitalization (ICD-9 codes of 491, 492, 493 or 496 in any position during follow-up).

Cancer, self-reported during follow-up, excluded non-melanoma skin cancer. Being under active treatment for cancer was an exclusion criterion at baseline.

Treated diabetes was defined by self-report of diabetes and use of oral hypoglycaemic medications or insulin.

Kidney disease was identified by self-report of a doctor’s diagnosis.

Poor self-reported health was used to capture severity of illness or other illnesses not already defined and was updated at each visit and not considered chronic.

Function measures

Physical and cognitive function measures included gait speed (15 feet, expressed in m/s), grip strength (average of three attempts in dominant hand) in kg, digit symbol substitution test (DSST)30 and the Modified Mini Mental Status Examination (3MSE).31 3MSE was measured at the first follow-up for the original cohort in 1990–91 and annually through 1998–99 and again in 2005–06. When available, 3MSE was estimated from the telephone instrument of cognitive function (TICS) as previously described.32 DSST and gait speed were measured at every clinic visit (annually from 1989–90 to 1998–99, and in 2005–06). Grip strength was measured at every clinic visit except the first follow-up on the original cohort in 1990–91.

Biomarkers

Based on the biological processes discussed above and previous prospective associations with disability or mortality, five biomarkers were repeated over time to determine their trajectories. The biomarkers were measured less frequently than the function measures. Adiponectin was measured at three time points, IL-6 and cystatin-C at four and IGF-1 and DHEAS up to five over 18 years. Biomarkers assayed by different laboratories or with different assays over time were harmonized by repeating measures using the new assay on a subset of participants with the previous assay and performing a mean shift or regression adjustment if indicated by analyses of the paired measures.

Fasting blood samples were collected and stored at each examination.33 Specific laboratory methods for each biomarker are as follows.

IGF-1 was measured after an extraction step using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Diagnostics Systems Laboratory, Webster, TX).2 IGF-1 assay coefficient of variation was 4–6%.

Plasma DHEAS was measured with a competitive immunoassay kit (Alpco Diagnostics, Windham, NH) with an inter-assay coefficient of variation of 3.8–7.2%.

IL-6 was measured by ultrasensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Quantikine HS Human IL-6 Immunoassay; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 2.9–8.7% and 7.3–9.0%, respectively.

Adiponectin was measured with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in 1992–93 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and in 1996–97 and 2005–06 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 2.5–4.7% and 5.8–6.9%, respectively.

Cystatin-C was measured by means of a particle-enhanced immunonephelometric assay (N Latex Cystatin C, Dade Behring) with a nephelometer (BNII, Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL).34

Potential confounders

Sociodemographic factors were assessed by interview and included race, sex and years of education. Weight was assessed on a calibrated scale with light clothing and no shoes. Height was assessed with a calibrated stadiometer.26

Analysis

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to estimate the mean value of each function measure and each biomarker at each observation time as a function of age, age2, age3 and current health status, separately for men and women. Higher-order age terms were included to allow for non-linear change with age. Interactions of the age terms with health status were assessed to allow for differing rates of change with age between those who remain healthy and those with chronic disease. Coefficients were retained in the model if significant at P < 0.01; this threshold was chosen due to multiple testing. GEE accounts for the correlation among repeated measures on a participant. Missing values of biomarker and function measures were linearly interpolated from previous and future values provided there were no more than three consecutive missing values. Given that decline over time in most of the function and biomarker measures was nonlinear, we did not want to assume a linear relationship over a longer period of time. No imputation was done beyond the last observed measure. Results were illustrated by plotting predicted values of the function measures by age, health status and sex.

In order to simultaneously view function and biomarker trajectories on the same scale for plotting, each measure was standardized by subtracting its overall mean and dividing by its standard deviation. Predicted values, transformed into standardized scales, were plotted together for multiple function and biomarker measures to illustrate the concurrent changes of biomarkers and function with age.

To determine which, if any, biomarkers tracked with the changes in the function measures after accounting for the associations with age and health status, each biomarker was standardized using the year 1992–93 values, then was added to each function measure model. Biomarker values were updated over time to track the simultaneous changes in biomarkers with function as the participants aged. The biomarker coefficient represents the average effect of one standard deviation higher value of the biomarker on the expected value of the function measure, given a participant’s age and health status. All models were adjusted for race, education and clinic site. The model for gait speed was additionally adjusted for height and the model for grip strength was additionally adjusted for weight. To assess the combined association of multiple biomarkers on function, individually significant biomarkers were included together in a model for each outcome.

Results

The cohort characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 72.8 years, 58% were women, and 15.6% were Black. Over one-third had a chronic disease or reported poor health at baseline.

Table 1.

Description of the cohort at baseline*

| Women | Men | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 3372 | N = 2474 | N = 5846 | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 72.5 (5.5) | 73.2 (5.7) | 72.8 (5.6) |

| Black race | 571 (16.9) | 341 (13.8) | |

| Education, years | 12.1 (3.0) | 12.4 (3.4) | 12.2 (3.2) |

| Height, cm | 159 (6.3) | 173 (6.6) | 165 (9.5) |

| Weight, kg | 67.9 (14.2) | 79.3 (12.6) | 72.7 (14.7) |

| Chronic disease | |||

| CVD | 698 (20.7) | 804 (32.5) | 1502 (25.7) |

| COPD | 261 (7.7) | 210 (8.5) | 471 (8.1) |

| Cancer1 | 55 (1.7) | 84 (3.5) | 139 (2.4) |

| Kidney disease1 | 40 (1.2) | 36 (1.5) | 76 (1.3) |

| Treated diabetes | 246 (7.3) | 247 (10.0) | 247 (493) |

| Poor health | 143 (4.2) | 89 (3.6) | 232 (4.0) |

| Any chronic disease | 1052 (31.2) | 1076 (43.5) | 2128 (36.4) |

| Function | |||

| Grip strength, N | 216 (59) | 364 (88) | 279 (103) |

| Gait speed, m/s | 0.83 (0.22) | 0.89 (0.21) | 0.86 (0.22) |

| 3MSE score2 | 90.2 (9.1) | 88.8 (9.9) | 89.6 (9.5) |

| DSST score | 37.9 (13.5) | 34.3 (13.1) | 36.4 (13.5) |

| Biomarkers | |||

| IGF1,3 µg/l | 89.4 (71-113) | 103 (82-127) | 95 (75-119) |

| Adiponectin,4 mg/l | 13.9 (9.9-19.6) | 9.9 (7.14-14.0) | 12.1 (8.4-17.3) |

| DHEAS,4 µg/ml | 0.52 (0.32-0.80) | 0.77 (0.48-1.15) | 0.61 (0.38-0.94) |

| IL-6, pg/ml | 1.74 (1.13-2.72) | 1.91 (1.34-2.94) | 1.83 (1.23-2.80) |

| Cystatin-C, mg/l | 0.97 (0.86-1.12) | 1.02 (0.91-1.19) | 0.99 (0.88-1.15) |

Entries in table are mean (sd) or median (interquartile range) or N (%).

*Total N = 5846; 42 persons excluded for lack of any biomarker or function data.

11 year after baseline.

2First administered 1 year after baseline for original cohort.

31993–94.

41992–93.

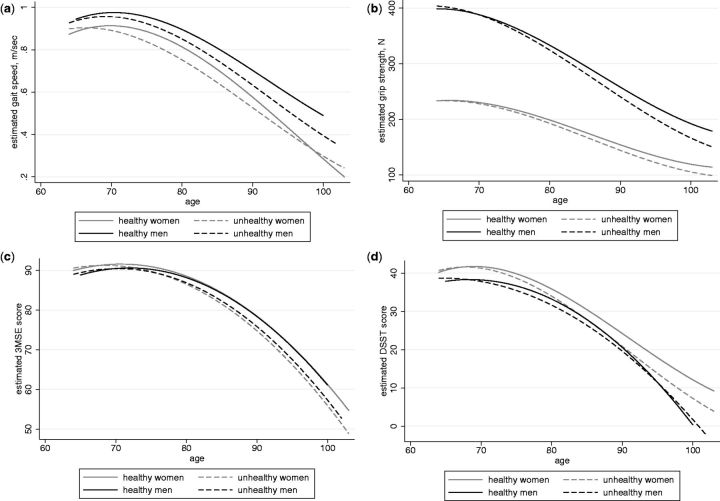

Estimated trajectories of decline with age in physical and cognitive function for men and women who remained healthy and those with chronic disease are shown in Figure 1. It is notable that regardless of health status, the average rates of decline in each of the function measures accelerated in older age in both men and women. Those who remained healthy had somewhat higher function over time than those who developed disease, but only slightly higher with a strong ageing effect accelerating at later ages. Table 2 provides the coefficients for age, age2 and age3 with interaction terms that correspond with these figures. Although some interactions between age terms and chronic disease were statistically significant, Figure 1 illustrates that the differences in the trajectories between those with disease vs without were very small. Grip strength showed the earliest decline with men starting much higher than women but with similar rates of decline. For gait speed and DSST, declines did not begin until after age 70, whereas for 3MSE, declines were not apparent until later in the 70s. Differences between men and women appeared to be minimal for 3MSE and larger for DSST, though all analyses were conducted separately for men and women and sex differences were not tested for statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of functional decline in women and men by health status. a) Gait speed; b) grip strength; c) Modified Mini Mental State Examination (3MSE); d) Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST).

Table 2.

Rates of change in function with age and powers of age stratified by chronic disease status, including test of interaction with chronic disease corresponding to Figure 1 a–d

| Women |

Men |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | Age* | Age2* | Age3* | Age* | Age2* | Age3* |

| Gait speed, m/s | ||||||

| Coefficient no chronic disease | −0.0138 | −0.00081 | 0.00001 | −0.0114 | −0.0007 | 0.000015 |

| Coefficient with chronic disease | −0.0167 | −0.00056 | 0.00001 | −0.0139 | −0.0007 | 0.000015 |

| P-value for interaction with disease | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.208 | < 0.001 | 0.586 | 0.688 |

| Grip strength, N | ||||||

| Coefficient no chronic disease | −3.68 | −0.0998 | 0.00379 | −6.26 | −0.1466 | 0.00498 |

| Coefficient with chronic disease | −4.07 | −0.0998 | 0.00379 | −7.11 | −0.1466 | 0.00498 |

| P-value for interaction with disease | < 0.001 | 0.341 | 0.915 | < 0.001 | 0.431 | 0.29 |

| 3MSE score | ||||||

| Coefficient no chronic disease | −0.444 | −0.0355 | 0 | −0.381 | −0.0374 | 0 |

| Coefficient with chronic disease | −0.609 | −0.0355 | 0 | −0.507 | −0.0374 | 0 |

| P-value for interaction with disease | < 0.001 | 0.789 | 0.182 | < 0.001 | 0.074 | 0.042 |

| DSST score | ||||||

| Coefficient no chronic disease | −0.764 | −0.0369 | 0.00088 | −0.653 | −0.0382 | 0 |

| Coefficient with chronic disease | −0.913 | −0.0369 | 0.00088 | −0.737 | −0.0291 | 0 |

| P-value for interaction with disease | < 0.001 | 0.311 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.723 |

*All of the non-zero age, age2 and age3 terms reported were significant at < 0.001. Age was centred at age = 77. P-values were assessed iteratively, beginning with interactions with age3 and reducing the model to eliminate the interaction if not significant at P < 0.01 before testing the next highest interaction. The final models retained only terms statistically significant at P < 0.01. A 0 coefficient indicates that the power of age was not significant and was dropped from the final model.

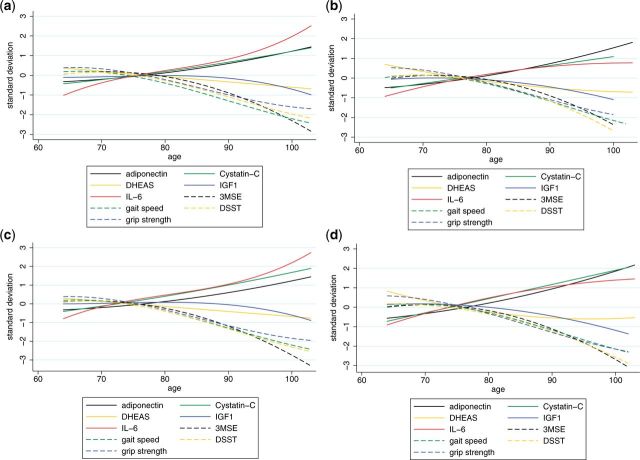

We next examined the trajectories of changes in biomarkers along with changes in function (Figure 2). Patterns of change in biomarkers with age varied, with DHEAS declining gradually with age and IGF-1 remaining stable until later years. IL-6, cystatin-C and adiponectin increased with age with similar magnitude to functional declines though opposite in direction. These patterns were similar among women and men. Again, the overall patterns did not differ in the group of individuals that remained healthy over the time period, compared with those with chronic disease, but levels of IL-6 and cystatin-C were higher in men and women with chronic disease than in those who remained healthy.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of function and biomarkers by health status in women and men. a) Healthy women; b) healthy men; c) unhealthy women; d) unhealthy men. DSST, Digit Symbol Substitution Test; 3MSE, Modified Mini Mental State Examination; IL-6, interleukin-6; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor; DHEAS, dihydroepiandrosterone sulphate.

Finally, we added the individual biomarkers to the functional trajectory models to determine if the changes in biomarkers tracked with the changes in function observed with age (Table 3). Note that the coefficients were expressed in standardized units to allow the relative strength of each association with function to be compared more directly with each other. The coefficients represent the average associations over time of the biomarkers with the function measures. For example, for cystatin-C in women, each standard deviation (34 ug/l) higher value of cystatin-C was associated with a −0.17 lower value of grip strength. Higher levels of adiponectin were associated with lower mean cognitive scores and grip strength over time in both men and women. Greater inflammation, as measured by IL-6, was associated with worse physical performance but not with cognitive performance. Higher levels of cystatin-C were associated with poorer cognitive and physical function across the board. DHEAS trajectory was associated only with grip strength in men and women and with gait speed in men. IGF-1 did not track with functional trajectories in men but there was an association between higher levels and slower gait speed and lower 3MSE scores in women.

Table 3.

Associations of individual standardizeda biomarker levels with function over time, adjusted for age, Black race, years of education and clinic

| Gait speed, m/s |

Grip strength, N |

3MSE |

DSST |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Coefficientc (95% CI) | P b | N | Coefficient*** (95% CI) | P b | N | Coefficient (95% CI) | P b | N | Coefficient (95% CI) | p b | |

| Women | ||||||||||||

| IGF-1, 33 ug/l | 2986 | −0.009 (−0.014, −0.004) | 0.001 | 2954 | 0.51 (−0.69, 1.70) | 0.407 | 2752 | −0.29 (−0.50, −0.08) | 0.007 | 2912 | 0.01 (−0.24, 0.27) | 0.915 |

| Adiponectin, 8 mg/l | 2830 | −0.002 (−0.008, 0.004) | 0.488 | 2813 | −2.33 (−3.77, −0.89) | 0.002 | 2846 | −0.46 (−0.67, −0.24) | < 0.001 | 2770 | −0.40 (−0.69, −0.11) | 0.008 |

| DHEAS, 0.52 ug/ml | 2888 | 0.008 (0.002, 0.015) | 0.016 | 2871 | 2.76 (1.19, 4.34) | 0.001 | 2837 | −0.04 (−0.31, 0.23) | 0.777 | 2841 | 0.18 (−0.16, 0.52) | 0.306 |

| IL-6, 2.2 pg/ml | 3288 | −0.013 (−0.018, −0.009) | < 0.001 | 3254 | −2.86 (−3.81, −1.90) | < 0.001 | 2778 | −0.21 (−0.39, −0.04) | 0.016 | 3249 | 0.04 (−0.16, 0.23) | 0.700 |

| Cystatin-C, 0.34 mg/l | 3300 | −0.026 (−0.031, −0.021) | < 0.001 | 3261 | −1.66 (−2.72, −0.61) | 0.002 | 2872 | −0.45 (−0.63, −0.27) | < 0.001 | 3256 | −0.43 (−0.66, −0.21) | <0.001 |

| Men | ||||||||||||

| IGF-1, 33 ug/l | 2123 | 0.001 (−0.005, 0.007) | 0.762 | 2100 | 0.11 (−1.93, 2.16) | 0.915 | 1943 | −0.17 (−0.41, 0.07) | 0.173 | 2064 | 0.26 (−0.02, 0.54) | 0.064 |

| Adiponectin, 8 mg/l | 2005 | −0.011 (−0.019, −0.002) | 0.016 | 1998 | −6.27 (−9.15, −3.39) | < 0.001 | 2013 | −0.53 (−0.85, −0.20) | 0.001 | 1953 | −0.65 (−0.10, −0.28) | 0.001 |

| DHEAS, 0.52 ug/ml | 2098 | 0.010 (0.004, 0.017) | 0.001 | 2089 | 2.77 (070, 4.84) | 0.009 | 2023 | 0.13 (−0.11, 0.37) | 0.282 | 2045 | 0.25 (−0.02, 0.53) | 0.074 |

| IL-6, 2.2 pg/ml | 2408 | −0.010 (−0.015, −0.005) | < 0.001 | 2385 | −6.27 (−7.80, −4.74) | < 0.001 | 1953 | −0.19 (−0.39, 0.02) | 0.075 | 2365 | −0.10 (−0.31, 0.10) | 0.312 |

| Cystatin-C, 0.34 mg/l | 2356 | −0.024 (−0.029, −0.019) | < 0.001 | 2337 | −6.10 (−7.70, −4.49) | < 0.001 | 2035 | −0.58 (−0.79, −0.38) | < 0.001 | 2305 | −0.68 (−0.90, −0.46) | <0.001 |

aBiomarkers in standard deviation units.

b P-values < 0.01 are in bold type.

cGait speed additionally adjusted for height, and grip strength additionally adjusted for weight.

When significant biomarkers were entered simultaneously in models for each measure of function as an outcome, the biomarkers with inconsistent relationships between men and women were no longer associated with functional trajectories in their respective models (Table 4). Higher levels of IL-6 tracked with lower gait speed and grip strength, DHEAS tracked with grip strength and cystatin-C tracked with poorer performance in almost all functional trajectories, except for grip strength in women. Higher adiponectin tracked with lower grip strength and poorer cognitive function except for DSST in women, with P = 0.015, just above our threshold of 0.01.

Table 4.

Associations of multiple standardizeda biomarker levels with function over time, adjusted for Black race, years of education and clinic

| Gait speed, m/s |

Grip strength, N |

3MSE |

DSST |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Coefficientc (95% CI) | P b | N | Coefficient*** (95% CI) | P b | N | Coefficient (95% CI) | P b | N | Coefficient (95% CI) | Psb | |

| Women | 2598 | 2712 | 2321 | 2769 | ||||||||

| IGF-1, 33 ugl | −0.006 (−0.012, −0.0005) | 0.033 | −0.13 (−0.36, 0.10) | 0.28 | ||||||||

| Adiponectin, 8 mg/l | −2.63 (−4.12, −1.15) | 0.001 | −0.42 (−0.67, −0.18) | 0.001 | −0.36 (−0.66, −0.07) | 0.015 | ||||||

| DHEAS, 0.52 ug/ml | 3.14 (1.38, 4.90) | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| IL-6, 2.2 pg/ml | −0.012 (−0.018, −0.007) | < 0.001 | −4.75 (−5.96, −3.55) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Cystatin-C, 0.34 mg/l | −0.023 (−0.029, −0.017) | < 0.001 | −1.25 (−2.55, 0.06) | 0.062 | −0.45 (−0.67, −0.23) | < 0.001 | −0.70 (−0.96, −0.43) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Men | 2050 | 1912 | 2012 | 1952 | ||||||||

| IGF-1, 33 ug/l | ||||||||||||

| Adiponectin, 8 mg/l | −5.51 (−8.52, −2.51) | < 0.001 | −0.46 (−0.79, −0.14) | 0.005 | −0.53 (−0.91, −0.15) | 0.006 | ||||||

| DHEAS, 0.52 ug/ml | 0.007 (0.0002, 0.013) | 0.043 | 3.45 (1.09, 5.81) | 0.004 | ||||||||

| IL-6, 2.2 pg/ml | −0.013 (−0.019, −0.007) | < 0.001 | −8.53 (−10.5, −6.56) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Cystatin-C, 0.34 mg/l | −0.025 (−0.031, −0.019) | < 0.001 | −4.03 (−6.01, −2.05) | < 0.001 | −0.65 (−0.87, −0.42) | < 0.001 | −0.93 (−1.19, −0.67) | < 0.001 | ||||

aBiomarkers in standard deviation units, model for each function measure included all biomarkers.

b P-values < 0.01 are in bold type; this threshold was chosen due to multiple testing.

cGait speed additionally adjusted for height, and grip strength additionally adjusted for weight.

Discussion

Functional decline with ageing in the Cardiovascular Health Study was substantial and accelerated in later life. The declines related to ageing were far greater than those related to chronic disease, though the healthy ageing group maintained a modestly higher level of function for most parameters with age. The similar accelerations of decline with ageing in those with and without major chronic disease suggest that functional declines are inevitable in late life as they are observed even in the absence of major chronic disease. This finding supports the idea that functional decline marks the underlying ageing process late in life.

Some, but not all, of the biomarkers showed similar trajectories with age. DHEAS and IGF-1, prominent hormonal markers related to key processes of ageing, did not decline as strongly with age as the function measures. Trajectories of IL-6, adiponectin and cystatin-C mirrored the decline in function in that the age acceleration increases were similar in magnitude and pattern but opposite in direction to the trajectories in physical and cognitive function. Cystatin-C was associated with most functional measures independently of the other biomarkers. IL-6 was independently associated only with physical decline. Except for gait speed, the pattern for adiponectin was similar to those in IL-6 and cystatin-C.

These associations suggest that IL-6, adiponectin and especially cystatin-C trajectories might be useful for tracking the ageing process and functional decline. Such measures might be more accessible in cohorts that do not have in-person performance measures or might be useful as intermediate outcome measures that are sensitive to interventions that ultimately target improved function. As an example, IL-6 levels can be reduced with several pharmacological interventions.35 The potential benefits of lowering IL-6 on gait speed or strength decline could be estimated from these data. Such a trial is currently beginning in the USA.36

There were some interesting differences in the functional trajectories that should be noted. First, the trajectory of decline in grip was apparent from age 65, the youngest age in CHS. Grip strength has been shown to predict adverse outcomes from middle age.37 Our data suggest that grip strength is able to detect change at an earlier age than the other function measures of gait speed, 3MSE and DSST. Decline in gait speed was not apparent until after age 70 and was only slightly lower in women. Similarly, DSST decline was not apparent until after age 70, whereas 3MSE did not show much decline until after the late 70s. It should be noted that the 3MSE is known to be inadequately challenging to reveal early decline.38

The biomarkers examined here are strongly age-related. Cystatin-C is more specific for a given organ (kidney) than the other measures although it also has documented relationships with non-renal risk factors that may contribute to its strong prognostic association with cardiovascular disease and death.39 Its strong relationship with function might suggest several hypotheses. One is that kidney function decline may influence other pathways such as elevated inflammation, lower vitamin D metabolism or metabolic acidosis.40,41 This is essentially a cross-sectional association of trajectories that could be related to a common causal factor such as underlying vascular disease,23 which itself is strongly age-related. We have demonstrated many times in CHS that vascular disease is critically important to function9,42,43 and, potentially, vascular trajectories could also track with functional decline. Kidney function is affected strongly by hypertension and diabetes, and could be a biological integrator of cumulative vascular stress from these risk factors over time. The trajectories of adiponectin and IL-6 could also be capturing onset and progression of vascular disease.44

Increases in adiponectin are associated with ageing-related weight loss, and a decrease in adipocyte size, much as is observed in the setting of critical illness.45 Such decrease in adipocyte size, reflecting altered energy homeostasis, has been associated with mortality in older adults independent of weight,45 and could likewise account for the link between adiponectin and functional decline documented here. Yet, although adiponectin is mostly derived from adipose tissue, this peptide may also be released by diseased skeletal muscle, as has been reported in the context of heart failure-related cachexia.21 The extent to which skeletal muscle production contributes to increases in circulating adiponectin with ageing and disease is unclear, but tracking of adiponectin with physical decline could also reflect onset of ageing-associated sarcopenia.45 Whatever its provenance, adiponectin may play an important role in effecting clearance of apoptotic bodies by macrophages,45 and its association with cognitive and physical deterioration is consistent with this view, such that its levels serve as a useful marker of homeostatic deterioration and disease.

Increases in IL-6 are thought to be fundamental to the ageing process but are also driven by inflammatory disease, obesity and smoking.20 Few studies have examined changes in inflammatory markers over time. In a previous analysis of repeated measures of IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP), we noted associations with functional decline as well as CVD events and total mortality in this cohort.19 This analysis extends these findings by showing that IL-6, cystatin-C and adiponectin trajectories have independent associations with decline in physical function.

The lack of much change in DHEAS and IGF-1 might suggest that their trajectories are relatively unrelated to functional decline. DHEAS trajectory was most strongly related to grip strength, perhaps reflecting the role of androgens in maintaining strength.46 We have previously reported that DHEAS instability, not captured in this analysis, was more important as a marker of ageing or disease than other components of the trajectory.18 IGF-1 trajectory was not related to trajectories of function in men. In women, higher IGF-1 levels were related lower 3MSE scores, but this association became non-significant after adjusting for IL-6, adiponectin and cystatin-C. An extensive literature on IGF-1 and cognition has shown neuroprotective effects of IGF-1 but also acceleration of neurodegeneration.47 The cause-and-effect relationship cannot be assessed here. Additionally, IGF-1 levels may not be as strongly related to function as its binding protein, IGFBP-1.2

To date, no single biomarker has proven to be an adequate surrogate for predicting the adverse consequences of ageing, such as functional decline, morbidity or mortality.48,49 More recent discoveries in the biology of ageing highlight the importance of DNA damage related to oxidative stress, radiation damage or telomere shortening.50 Telomere length in peripheral blood leukocytes has been linked to age-related disease and mortality in humans, but current methods are not adequately sensitive to document changes or reliably predict outcomes.51 Other markers of ageing processes such as51 DNA methylation,52–54 gene expression,55,56 advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs)57 and perhaps Klotho58 have recently been shown to predict mortality or disability in human populations and warrant further assessment. However, these measures are currently expensive, especially if repeated over time. Our approach of comparing trajectories of function with biomarker trajectories could be informative in validating these new biomarkers as biomarkers of ageing. Perhaps some of these newer biomarkers of ageing would be more informative across multiple measures of functional decline.

Strengths of this analysis include the large cohort, well-characterized for health events and function with repeated measures over many years. We were limited in the choice of biomarkers with repeated assessments to those initially assessed over 10 years ago. Health status was dichotomized such that the unhealthy group included people with prevalent and incident chronic illnesses, thus it is a heterogeneous group. Trajectories could vary for specific conditions. It is important to recognize that the models estimate trajectories over a wider age span than was observed for any individual participant, with each participant contributing observations over a varying period of time at starting ages ranging from age 65 to over 85 years of age. There is wide variability in individual trajectories that is not captured with this approach.

In summary, trajectories of functional decline showed strong age acceleration late in life in healthy as well as chronically ill older adults. Grip strength appeared to decline earlier than gait, 3MSE or DSST, and adiponectin, IL-6 and especially cystatin-C tracked with functional decline.

Funding

This research was supported by AG023629 from the National Institute on Ageing (NIA) and contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, N01 HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083 and N01HC85086, and grant HL080295, from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional support was provided by the University of Pittsburgh Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center: P30-AG-024827.

Acknowledgements

A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at [CHS-NHLBI.org]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Semba RD, Bandinelli S, Sun K, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Relationship of an advanced glycation end product, plasma carboxymethyl-lysine, with slow walking speed in older adults: the InCHIANTI study. Eur J Appl Physiol 2010;108:191–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaplan RC, McGinn AP, Pollak MN. et al. Total insulinlike growth factor 1 and insulinlike growth factor binding protein levels, functional status, and mortality in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:652–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanders JL, Cappola AR, Arnold AM. et al. Concurrent change in dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and functional performance in the oldest old: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010. ;65:976–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanders JL, Ding V, Arnold AM. et al. Do changes in circulating biomarkers track with each other and with functional changes in older adults? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014. 2014;69A:174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Newman AB, Arnold AM, Sachs MC. et al. Long‐term function in an older cohort—the Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:432–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ryan A, Wallace E, O’Hara P, Smith SM. Multimorbidity and functional decline in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. White DK, Neogi T, Nevitt MC. et al . Trajectories of gait speed predict mortality in well-functioning older adults: the Health, Ageing and Body Composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68:456–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stenholm S, Westerlund H, Head J. et al. Comorbidity and functional trajectories from midlife to old age: the Health and Retirement Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015;70:332–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosano C, Kuller LH, Chung H, Arnold AM, Longstreth WT, Newman AB. Subclinical brain magnetic resonance imageing abnormalities predict physical functional decline in high‐functioning older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:649–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fried LF, Lee JS, Shlipak M. et al. Chronic kidney disease and functional limitation in older people: health, ageing and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:750–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cappola AR, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Volpato S, Fried LP. Insulin-like growth factor I and interleukin-6 contribute synergistically to disability and mortality in older women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:2019–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boyd CM, Ricks M, Fried LP. et al. Functional decline and recovery of activities of daily living in hospitalized, disabled older women: the Women's Health and Ageing Study I. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1757–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, Lipson S, Guralnik JM. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA 2003;289:2387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span - from yeast to humans. Science 2010;328:321–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roubenoff R, Parise H, Payette HA. et al. Cytokines, insulin-like growth factor 1, sarcopenia, and mortality in very old community-dwelling men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Med 2003;115:429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cappola AR, O’Meara ES, Guo W, Bartz TM, Fried LP, Newman AB. Trajectories of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate predict mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:1268–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vermeulen A. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and ageing. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1995;774:121–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cappola AR, Xue Q-L, Walston JD. et al. DHEAS levels and mortality in disabled older women: the Women's Health and Ageing Study I. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:957–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jenny NS, French B, Arnold AM. et al. Long-term assessment of inflammation and healthy ageing in late life: the Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012;67:970–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Singh T, Newman AB. Inflammatory markers in population studies of ageing. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10:319–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Berendoncks AM, Garnier A, Beckers P. et al. Functional adiponectin resistance at the level of the skeletal muscle in mild to moderate chronic heart failure. Circulation 2010;3:185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Odden MC, Tager IB, Gansevoort RT. et al. Age and cystatin C in healthy adults: a collaborative study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:463–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Katz R. et al . Cystatin C and the risk of death and cardiovascular events among elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2049–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kizer JR, Benkeser D, Arnold AM. et al. Associations of total and high-molecular-weight adiponectin with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in older persons: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 2012;126:2951–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tell GS, Fried LP, Hermanson B, Manolio TA, Newman AB, Borhani NO. Recruitment of adults 65 years and older as participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 1993;3:358–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P. et al. The cardiovascular health study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol 1991;1:263–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE. et al. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 1995;5:278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D. et al. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 1995;5:270–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Diehr P, Williamson J, Patrick DL, Bild DE, Burke GL. Patterns of Self‐rated health in older adults before and after sentinel health events. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised. New York, NY: Psychological Corp, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee Teng E, Chang Hui H. The modified mini-mental state (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48:314–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arnold AM, Newman AB, Dermond N, Haan M, Fitzpatrick A. Using telephone and informant assessments to estimate missing Modified Mini-Mental State Exam scores and rates of cognitive decline. Neuroepidemiology 2009;33:55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cushman M, Cornell ES, Howard PR, Bovill EG, Tracy RP. Laboratory methods and quality assurance in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Clin Chem 1995;41:264–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Erlandsen EJ, Randers E, Kristensen JH. Evaluation of the Dade Behring N Latex Cystatin C assay on the Dade Behring Nephelometer II System. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1999;59:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ridker PM, Lüscher TF. Anti-inflammatory therapies for cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1782–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clinical Trials. gov. The ENRGISE (ENabling Reduction of Low-Grade Inflammation in SEniors) Pilot Study, Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT02676466. [Web page]. 2016; ENRGISE Pilot Study will test the ability of anti-inflammatory interventions for preventing major mobility disability by improving or preserving walking ability. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02676466. (10 May 2016, date last accessed).

- 37. Rantanen T, Harris T, Leveille SG. et al. Muscle strength and body mass index as long-term predictors of mortality in initially healthy men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55:M168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lopez OL, Kuller LH, Fitzpatrick A, Ives D, Becker JT, Beauchamp N. Evaluation of dementia in the cardiovascular health cognition study. Neuroepidemiolog 2003;22:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Arnlov J. et al. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med 2013;369:932–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu CK, Lyass A, Massaro JM, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Fox CS, Murabito JM. Chronic kidney disease defined by cystatin C predicts mobility disability and changes in gait speed: the Framingham Offspring Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69:301–07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keller C, Katz R, Sarnak MJ. et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and decline in kidney function in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Newman AB, Arnold AM, Naydeck BL. et al. Successful ageing: effect of subclinical cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fitzpatrick AL, Lopez OL, Kuller LH. (eds). Mid- And Late Life Obesity: Risk of Dementia in the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. Washington, DC: Alzheimers Association, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kizer JR, Arnold AM, Jenny NS. et al. Longitudinal changes in adiponectin and inflammatory markers and relation to survival in the oldest old: the Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:1100–07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kizer JR. Adiponectin, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: Parsing the dual prognostic implications of a complex adipokine. Metabolism 2014;63:1079–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Valenti G, Denti L, Maggio M. et al. Effect of DHEAS on skeletal muscle over the life span: The InCHIANTI Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:M466–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Deak F, Sonntag WE. Ageing, synaptic dysfunction, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012;67:611–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baker GT, Sprott RL. Biomarkers of ageing. Exp Gerontol 1988;23:223–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bürkle A, Moreno-Villanueva M, Bernhard J. et al. MARK-AGE biomarkers of ageing. Mech Ageing Dev 2015;151:2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A. et al. Geroscience: linking ageing to chronic disease. Cell 2014;159:709–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sanders JL, Newman AB. Telomere length in epidemiology: a biomarker of ageing, age-related disease, both, or neither? Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35:112–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Feinberg AP, Fallin MD. Epigenetics at the crossroads of genes and the environment. JAMA 2015;314:1129–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol 2013;14:R115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Marioni RE, Shah S, McRae AF. et al. DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol 2015;16:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Weindruch R, Kayo T, Lee C-K, Prolla TA. Gene expression profiling of ageing using DNA microarrays. Mech Ageing Dev 2002;123:177–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pilling LC, Joehanes R, Melzer D. et al. Gene expression markers of age-related inflammation in two human cohorts. Exp Gerontol 2015;70:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Semba RD, Nicklett EJ, Ferrucci L. Does accumulation of advanced glycation end products contribute to the ageing phenotype? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010;65:963–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Semba RD, Cappola AR, Sun K. et al. Plasma klotho and mortality risk in older community-dwelling adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:794–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]