Abstract

Background: High left ventricular mass (LVM) is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality, but information relating LVM in older age to growth in early life is limited. We assessed the relationship of birthweight, height and body mass index (BMI) and overweight across childhood and adolescence with later life left ventricular (LV) structure.

Methods: We used data from the MRC National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD) on men and women born in 1946 in Britain and followed up ever since. We use regression models to relate prospective measures of birthweight and height and BMI from ages 2–20 years to LV structure at 60–64 years.

Results: Positive associations of birthweight with LVM and LV end diastolic volume (LVEDV) at 60–64 years were largely explained by adult height. Higher BMI, greater changes in BMI and greater accumulation of overweight across childhood and adolescence were associated with higher LVM and LVEDV and odds of concentric hypertrophy. Those who were overweight at two ages in early life had a mean LVM 11.5 g (95% confidence interval: -2.19,24.87) greater, and a mean LVEDV 10.0 ml (3.7,16.2) greater, than those who were not overweight. Associations were at least partially mediated through adult body mass index. Body size was less consistently associated with relative wall thickness (RWT), with the strongest association being observed with pubertal BMI change [0.007 (0.001,0.013) per standard deviation change in BMI 7–15 years]. The relationships between taller childhood height and LVM and LVEDV were explained by adult height.

Conclusions: Given the increasing levels of overweight in contemporary cohorts of children, these findings further emphasize the need for effective interventions to prevent childhood overweight.

Keywords: Birthweight, growth, overweight, left ventricular structure, birth cohort, life course

Key Messages

High left ventricular mass is independently associated with cardiovascular disease, and changes in left ventricular structure have been observed in overweight children.

Associations between increasing birthweight and higher left ventricular mass and end diastolic volume are explained by adult height, and thus largely reflect normal somatic growth.

High BMI and overweight in childhood and adolescence and accumulation of overweight across the life course are associated with greater left ventricular mass and left ventricular end diastolic volume, with associations being at least partially mediated through adult body mass index.

Given the increasing levels of overweight in contemporary cohorts of children, the need for effective interventions to reduce childhood overweight is highlighted, in order to prevent altered left ventricular structure.

Introduction

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and high left ventricular mass (LVM) are independent predictors of adult cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.1 LV structure changes with age and is thus an important intermediate marker of disease risk. Studies have documented tracking of body size and LVM across childhood,2–4 and adiposity in childhood is one of the two major factors [blood pressure (BP) being the other] that lead to excessive cardiac growth beyond that expected to accompany normal somatic growth in children.5 In the Generation R study, overweight and obese children have been found to show cardiac adaptations by the age of 2 years.6 The same study also found higher birthweight, a marker of fetal growth, to be associated with higher LVM at age 2 years.7 Similar associations have been observed in studies with LVM measured at age 9 years8 and 15 years,9 although associations were attenuated after adjustment for current height and weight.

The few existing studies investigating the longer-term associations of prenatal and postnatal growth have found no association between birthweight and LVM in adulthood.10–12 In contrast, another study has reported that being born preterm was associated with higher LVM indexed to body surface area in young adulthood.13 There is also evidence of an association between higher weight in early postnatal life and lower LVM in adulthood.11,12 However, these existing studies included samples of less than 500 and may therefore have lacked the power to detect relatively small associations, and did not assess adiposity development past infancy.

In the Bogalusa Heart Study, adiposity beginning in childhood was related to higher LVM index (LVMI) and LVH in early adulthood.14–16 A few other studies suggest that high body mass index (BMI) in adolescence or early adulthood is associated with higher LVM up to 20 years later.17,18 However, these existing studies have not considered measures of body size from different stages of early life in the same individuals, to investigate possible sensitive periods of development when the accumulation of adiposity may have particularly detrimental effects. Short adult height (and particularly short leg length) represents the impact of environmental factors in early childhood,19 and has consistently been associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes and mortality.20

To our knowledge there are no studies that assess the associations between childhood and adolescent BMI and height change, and echocardiographic measures past mid life. Most research has focussed on BMI and adiposity in early life, and information relating height growth to cardiac structure in adulthood is scarce.

Using data from the MRC National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD), a birth cohort study of men and women born in Britain in 1946, we aimed first to assess the relationship of birthweight and subsequent childhood and adolescent change in height and BMI with LV structure at age 60–64 years, assessing whether height and BMI in earlier life were associated with LV structure over and above the association with current body size. We assessed whether particular periods of growth were more strongly related with the outcomes and whether greater accumulation of overweight across childhood and adolescence was associated with LV structure. Finally, we assessed whether any observed associations were mediated by adult cardiovascular (CV) risk factors.

Methods

The Medical Research Council (MRC) National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD) is based on a nationally representative sample of 5362 births out of all the single births to married mothers that occurred in 1 week in March 1946 in England, Scotland and Wales.21 The cohort has been followed up 23 times, with the most recent data collection in 2006–10 when participants were 60–64 years old.22 Study members still alive and with a known current address in England, Scotland or Wales were invited for an assessment at one of six clinical research facilities (CRF) or to be visited by a research nurse at home. Invitations were not sent to those who had died (N = 778), who were living abroad (N = 570), had previously withdrawn from the study (N = 594) or had been lost to follow-up (N = 564). Of the 2856 invited participants, 2229 (78%) were assessed: 1690 (59%) attended a CRF and the remaining 539 were visited at home. The participating sample remains broadly representative of native-born British men and women of the same age.23

Ethical approval was obtained from the Greater Manchester Local Research Ethics Committee and the Scotland Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from the study members for each component of each data collection.

Echocardiographic measurement

Of the 1690 participants who attended a clinic, 1653 underwent echocardiography using GE Vivid I machines and 1617 had analysable images (96%). Echocardiographic images were obtained from parasternal long axis and short axis, apical 5-chamber, 4-chamber, 3-chamber, 2-chamber and aortic views along with conventional and tissue Doppler in the 4-chamber view. Image analysis was carried out by a cardiologist (A.K.G.) and two experienced cardiac physiologists masked to participant identity, using GE EchoPac software. Wall and chamber measurements were made according to American Society of Echocardiography (ASE)/European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) guidelines. LVM, LV end diastolic volume (LVEDV) and relative wall thickness (RWT) were calculated using the ASE-recommended formulae.24 A categorical variable representing LV remodelling was derived and the normal group [normal LVMI indexed for body surface area (BSA) and normal RWT] was compared with eccentric LVH (increased LVMI and normal RWT), concentric LVH (increased LVMI and increased RWT) and concentric remodelling (normal LVMI and increased RWT).24

Echocardiographers and readers underwent standardized training, periodic review and refresher sessions; phantom scans were performed annually on all machines and a continuous quality control audit of scans with feedback was carried out. A reproducibility study found excellent inter- and intra-reader reproducibility (intra-class correlation coefficients were > 0.9 for most measurements).

Anthropometry and covariates

Birthweights, recorded to the nearest quarter of a pound, were extracted from medical records. Weight and height measured at ages 2, 4, 6, 7, 11, 15 and 60–64 years and self-reported at 20 years were used to calculate BMI. Overweight or obese and underweight at each age was defined according to age-specific cut-offs.25

Childhood socioeconomic position (SEP) was measured by father's occupational social class and categorized according to the Registrar General's classification, and adult SEP by own occupation at age 53 years. Sitting heart rate (HR) and brachial blood pressure (BP) were measured using an Omron HEM-705 with an appropriately sized cuff after a 5-min rest. The second measurement was used in analyses, or the first measure where the second was missing. Type 2 diabetes status was based on self-reports of doctor diagnosis.

Statistical methods

Regression models were used to separately relate birthweight and each pair of childhood and adolescent BMI and height to LVM, RWT and LVEDV. Tests for sex x body size interactions were also carried out; there was no evidence of any sex differences in any association, so all are presented from sex combined models with an adjustment for sex. Childhood and adult SEP were then added to the models and birthweight for the BMI and height models. Additional adjustments for current BMI and height were added; non-linear terms and sex interactions were used where appropriate after investigation in preliminary models including only adult height, BMI and sex.

In order to assess the impact of differential growth over the period of childhood and adolescence, conditional change in BMI and height between the selected ages of 2–4, 4–7, 7–15 and 15–20 years was calculated. The conditional change variables were derived by regressing BMI (or height) at time (t) on BMI (or height) at t-1 for each sex and extracting standardized residuals. Analyses were adjusted for the confounders and then additionally for CV risk factors. In order to assess accumulation of overweight, we selected ages 4 (early childhood), 7 (later childhood) and 15 (adolescence) to represent different stages of early life. We defined the number of times (0–3) that an individual had been recorded as overweight or obese, and related this variable to the outcomes. Adjustments were carried out for confounders, and then current height and overweight were added in order to assess whether overweight in childhood and adolescence is associated with LV outcomes even among normal weight adults. Subsequently, CV risk factors were also adjusted for in a model without current body size.

Sensitivity analyses were carried out, repeating the analyses with LVMI and LVEDVI (indexed first to BSA and second to height2,7) as the outcomes. In these models, adjustment was not made for body size as body size is already accounted for by the indexation.

Finally, analyses were repeated for LV remodelling as the outcome using multinomial logistic regression. There was insufficient statistical power to adequately investigate accumulation of overweight and LV remodelling.

Results

A total of 782 men and 835 women had at least one outcome measure and at least one early life body size measure; adult BMI and height and descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1. In this maximum analytical sample, mean LV measures were all higher in men than women. The percentage of men and women with concentric and eccentric hypertrophy was similar, but a slightly higher percentage of men had concentric remodelling. In the total sample contacted at age 60–64, those included in these analyses were taller throughout life, had lower BMI at age 60–64 and were more likely to be from a non-manual social class in childhood and adulthood compared with those not included.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample from the MRC National Survey of Health and Development with at least one echocardiographic outcome, adult body size and at least one early life body size measure

| Men |

Women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Mean | SD | N (%) | Mean | SD | |

| Left ventricular mass (g) | 700 | 209.2 | 60.3 | 775 | 156.0 | 45.7 |

| Left ventricular end diastolic volume (ml) | 762 | 112.4 | 29.8 | 804 | 84.6 | 20.2 |

| Relative wall thickness | 700 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 775 | 0.41 | 0.09 |

| Left ventricular remodelling | 700 | 775 | ||||

| Normal | 286 (40.9%) | 343 (44.3%) | ||||

| Eccentric hypertrophy | 99 (14.1%) | 113 (14.6%) | ||||

| Concentric hypertrophy | 113 (16.1%) | 126 (16.3%) | ||||

| Concentric remodelling | 202 (28.9%) | 193 (24.9%) | ||||

| BMI at age 60–64y (kg/m2) | 782 | 27.7 | 4.0 | 835 | 27.5 | 5.2 |

| Height 60–64 (cm) | 782 | 175.3 | 6.5 | 835 | 162.1 | 5.8 |

| Birthweight (kg) | 782 | 3.45 | 0.51 | 835 | 3.35 | 0.47 |

| BMI 2y (kg/m2) | 619 | 18.0 | 2.5 | 641 | 17.5 | 2.3 |

| BMI 4y (kg/m2) | 685 | 16.4 | 1.7 | 717 | 16.1 | 1.6 |

| BMI 6y (kg/m2) | 632 | 15.9 | 1.3 | 675 | 15.7 | 1.4 |

| BMI 7y (kg/m2) | 655 | 15.9 | 1.3 | 700 | 15.7 | 1.5 |

| BMI 11y (kg/m2) | 652 | 17.2 | 2.1 | 700 | 17.4 | 2.4 |

| BMI 15y (kg/m2) | 608 | 19.5 | 2.3 | 646 | 20.6 | 2.7 |

| BMI 20y (kg/m2) | 628 | 22.4 | 2.3 | 706 | 21.7 | 2.8 |

| Height 2y (cm) | 639 | 86.1 | 5.1 | 668 | 85.1 | 4.3 |

| Height 4y (cm) | 694 | 103.7 | 4.9 | 734 | 103.5 | 4.9 |

| Height 6y (cm) | 661 | 114.9 | 5.0 | 697 | 114.4 | 5.1 |

| Height 7y (cm) | 675 | 120.7 | 5.3 | 727 | 120.4 | 5.2 |

| Height 11y (cm) | 657 | 141.2 | 6.6 | 709 | 142.0 | 6.8 |

| Height 15y (cm) | 618 | 162.7 | 8.9 | 655 | 159.4 | 6.0 |

| Height 20y (cm) | 642 | 177.4 | 6.5 | 714 | 163.1 | 6.0 |

| SBP 60–64y (mmHg) | 780 | 139 | 18 | 833 | 133 | 18 |

| DBP 60–64y (mmHg) | 780 | 79 | 10 | 833 | 76 | 9 |

| Resting heart rate 60–64y (beats/min) | 780 | 67 | 11 | 833 | 70 | 11 |

| Self-reported type 2 diabetes 60–64y | 704 | 772 | ||||

| No | 667 (94.7%) | 738 (95.6%) | ||||

| Yes | 37 (5.3%) | 34 (4.4%) | ||||

y, years.

Birthweight

Birthweight exhibited a non-linear relationship with LVM such that LVM increased with increasing birthweight, with a levelling off or even slight decrease at higher birthweights (Table 2). The association became more non-linear when adjusting for current BMI and height (Table 2). There was no evidence of an association between birthweight and LVMI indexed to either BSA or height2,7 (Supplementary Data, available as Supplementary Data at IJE online). LVEDV increased with increasing birthweight with the relationship being considerably attenuated after adjustment for current BMI and height (Table 3). Adjusting for BMI and height separately indicated that attenuation was a result of adjustment for height rather than BMI, a finding which is consistent with the null association observed with LVEDVI (Supplementary Data, available as Supplementary Data at IJE online). There was little evidence of a relationship between birthweight and RWT (Table 4).

Table 2.

Mean difference (and 95% confidence interval) in left ventricular mass (g) by birthweight and each pair of BMI and height in childhood and adolescence: models adjusted for: sex only (model 1); sex and confounders (model 2); sex, confounders, and BMI and height at 60–64 years (model 3)

| Adjusted for sex (model 1) |

Model 1 + additionally adjusted for childhood and adult social class and (except#) birthweight (model 2) |

Model 2+ additionally adjusted for BMI, BMI x sex and height at 60–64 years (model 3) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient | (95% CI) | P-value | Regression coefficient | (95% CI) | P-value | Regression coefficient | (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Birthweight# (per kg) (n = 1392) | 6.4 | (0.6,12.1) | 0.03* | 6.4 | (0.7,12.1) | 0.03* | 1.7 | (−3.7,7.0) | 0.5* |

| Categories | |||||||||

| <2.5 kg | −9.1 | (−26.8,8.7) | 0.1 | −11.0 | (−28.7,6.8) | 0.08 | −8.3 | (−24.3,7.8) | 0.5 |

| 2.5–3.0 kg | −5.2 | (−13.3,3.0) | −5.0 | (−3.1,3.1) | −3.3 | (−10.7,4.0) | |||

| 3.0–3.5 kg | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| 3.5–4.0 kg | 6.0 | (−0.7,12.7) | 6.1 | (−0.6,12.8) | 2.2 | (−3.9,8.2) | |||

| 4.0–4.5 kg | 2.6 | (−8.7,13.9) | 2.0 | (−9.2,13.3) | −4.2 | (−14.5,6.1) | |||

| > = 4.5 kg | −2.0 | (−21.7,17.6) | −2.1 | (−21.6,17.5) | −3.5 | (−21.2,14.2) | |||

| BMI (per kg/m2) | |||||||||

| 2 years (n = 1106) | 2.1 | (0.5,3.7) | 0.01 | 2.2 | (0.5,3.9) | 0.01 | 0.5 | (−1.1,2.1) | 0.5 |

| 4 years (n = 1256) | 3.6 | (1.9,5.4) | <0.001* | 3.4 | (1.6,5.2) | <0.001* | 1.5 | (−0.1,1.3) | 0.08* |

| Categories | |||||||||

| Lowest fifth | Ref. | <0.001 | Ref. | <0.001 | Ref. | 0.09 | |||

| 2 | 6.6 | (−2.3,15.5) | 6.0 | (−2.9,14.9) | 0.0 | (−8.1,8.0) | |||

| 3 | 8.9 | (0.2,17.7) | 8.4 | (−0.4,17.2) | 3.0 | (−5.0,11.0) | |||

| 4 | 20.4 | (11.2,29.7) | 19.5 | (10.3,28.8) | 10.4 | (1.9,18.8) | |||

| Highest fifth | 16.2 | (7.2,25.1) | 15.0 | (5.9,24.1) | 5.5 | (−2.9,13.9) | |||

| 6 years (n = 1176) | 4.8 | (2.6,7.0) | <0.001 | 4.5 | (2.2,6.7) | <0.001 | 1.2 | (−0.9,3.3) | 0.3 |

| 7 years (n = 1217) | 4.4 | (2.3,6.4) | <0.001 | 4.2 | (2.1,6.3) | <0.001 | 1.3 | (−0.7,3.3) | 0.2 |

| 11 years (n = 1219) | 2.4 | (1.1,3.7) | <0.001 | 2.1 | (0.8,3.5) | 0.001 | −0.6 | (−1.9,0.7) | 0.4 |

| 15 years (n = 1134) | 3.8 | (2.6,5.0) | <0.001 | 3.6 | (2.4,4.8) | <0.001 | 1.1 | (−0.1,2.4) | 0.07 |

| 20 years (n = 1185) | 4.4 | (3.3,5.6) | <0.001 | 4.2 | (3.0,5.3) | <0.001 | 0.4 | (−0.8,1.6) | 0.5 |

| Height (per cm) | |||||||||

| 2 years (n = 1106) | 1.6 | (0.8,2.4) | <0.001 | 1.8 | (0.1,2.7) | <0.001 | 0.6 | (−0.2,1.5) | 0.2 |

| 4 years (n = 1256) | 1.2 | (0.6,1.8) | <0.001 | 1.4 | (0.8,2.0) | <0.001 | 0.6 | (−0.1,1.3) | 0.1 |

| 6 years (n = 1176) | 1.1 | (0.5,1.7) | <0.001 | 1.4 | (0.8,2.0) | <0.001 | 0.3 | (−0.4,1.0) | 0.5 |

| 7 years (n = 1217) | 1.1 | (0.6,1.7) | <0.001 | 1.3 | (0.8,1.9) | <0.001 | 0.5 | (−0.3,1.2) | 0.2 |

| 11 years (n = 1219) | 0.9 | (0.5,1.3) | <0.001 | 1.0 | (0.6,1.5) | <0.001 | 0.4 | (−0.1,1.0) | 0.1 |

| 15 years (n = 1134) | 0.6 | (0.2,1.0) | 0.005 | 0.6 | (0.2,1.0) | 0.003 | −0.2 | (−0.7,0.4) | 0.5 |

| 20 years (n = 1185) | 1.1 | (0.6,1.5) | <0.001 | 1.3 | (0.8,1.8) | <0.001 | 1.0 | (−0.1,2.0) | 0.08 |

*Evidence of non-linearity.

Table 3.

Mean difference (and 95% confidence interval) in left ventricular end diastolic volume (ml) by birthweight and each pair of BMI and height in childhood and adolescence: models adjusted for sex only (model 1); sex and confounders (model 2); sex, confounders and BMI and height at 60–64 years (model 3)

| Adjusted for sex (model 1) |

Model 1 + additionally adjusted for childhood and adult social class and (except#) birthweight (model 2) |

Model 2 + additionally adjusted for BMI, BMI x sex and height at 60–64 years (model 3) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient | (95% CI) | P-value | Regression coefficient | (95% CI) | P-value | Regression coefficient | (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Birthweight# (per kg) (n = 1474) | 3.4 | (0.8,6.1) | 0.01 | 3.5 | (0.8,6.1) | 0.01 | 0.8 | (−1.8,3.3) | 0.6 |

| BMI (per kg/m2) | |||||||||

| 2 years (n = 1180) | 1.7 | (0.9,2.4) | <0.001 | 1.6 | (0.8,2.4) | <0.001 | 0.8 | (0.1,1.6) | 0.04 |

| 4 years (n = 1330) | 1.4 | (0.6,2.3) | 0.001* | 1.3 | (0.5,2.2) | 0.002* | 0.6 | (−0.2,1.4) | 0.2 |

| Categories | |||||||||

| Lowest fifth | Ref. | 0.004 | Ref. | 0.006 | |||||

| 2 | 3.1 | (−1.1,7.3) | 3.0 | (−1.2,7.2) | |||||

| 3 | 6.1 | (2.0,10.3) | 6.0 | (1.8,10.1) | |||||

| 4 | 7.0 | (2.7,11.4) | 6.8 | (2.5, 11.2) | |||||

| Highest fifth | 6.7 | (2.5,11.0) | 6.6 | (2.3,10.8) | |||||

| 6 years (n = 1240) | 2.1 | (1.1,3.2) | <0.001 | 2.1 | (1.0,3.1) | <0.001 | 1.0 | (−0.1,2.0) | 0.07 |

| 7 years (n = 1285) | 2.2 | (1.2,3.1) | <0.001 | 2.2 | (1.2,3.2) | <0.001 | 1.2 | (0.3,2.2) | 0.01 |

| 11 years (n = 1289) | 1.2 | (0.6,1.9) | <0.001 | 1.2 | (0.6,1.9) | <0.001 | 0.5 | (−0.2,1.1) | 0.2 |

| 15 years (n = 1196) | 1.7 | (1.1,2.2) | <0.001 | 1.7 | (1.1,2.2) | <0.001 | 0.9 | (0.3,1.5) | 0.002 |

| 20 years (n = 1254) | 2.2 | (1.7,2.7) | <0.001 | 2.2 | (1.7,2.7) | <0.001 | 1.1 | (0.5,1.6) | <0.001 |

| Height (per cm) | |||||||||

| 2 years (n = 1180) | 0.9 | (0.5,1.3) | <0.001 | 0.9 | (0.5,1.3) | <0.001 | 0.3 | (−0.2,0.7) | 0.2 |

| 4 years (n = 1330) | 0.6 | (0.4,0.9) | <0.001 | 0.6 | (0.3,0.9) | <0.001 | 0.2 | (−0.2,0.5) | 0.4 |

| 6 years (n = 1240) | 0.7 | (0.5,1.0) | <0.001 | 0.8 | (0.5,1.2) | <0.001 | 0.2 | (−0.2,0.6) | 0.3 |

| 7 years (n = 1285) | 0.7 | (0.4,0.9) | <0.001 | 0.7 | (0.4,1.0) | <0.001 | 0.2 | (−0.2,0.5) | 0.4 |

| 11 years (n = 1289) | 0.5 | (0.3,0.7) | <0.001 | 0.5 | (0.3,0.7) | <0.001 | 0.1 | (−0.2,0.4) | 0.5 |

| 15 years (n = 1196) | 0.4 | (0.2,0.6) | <0.001 | 0.4 | (0.2,0.6) | <0.001 | 0.0 | (−0.2,0.2) | 0.8 |

| 20 years (n = 1254) | 0.6 | (0.4,0.9) | <0.001 | 0.6 | (0.4,0.9) | <0.001 | 0.1 | (−0.4,0.6) | 0.7 |

*Evidence of non-linearity.

Table 4.

Mean difference (and 95% confidence interval) in relative wall thickness by birthweight and each pair of BMI and height in childhood and adolescence: models adjusted for sex only (model 1); sex and confounders (model 2); sex, confounders and BMI and height at 60–64 years (model 3)

| Adjusted for sex (model 1) |

Model 1 + additionally adjusted for childhood and adult social class and (except#) birthweight (model 2) |

Model 2 + additionally adjusted for BMI, BMI x sex and height at 60–64 years (model 3) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient | (95% CI) | P-value | Regression coefficient | (95% CI) | P-value | Regression coefficient | (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Birthweight# (per kg) (n = 1392) | −0.0060 | (−0.0179,0.0007) | 0.2 | −0.0061 | (−0.0156,0.0034) | 0.2 | −0.0046 | (−0.0142,0.0051) | 0.4 |

| BMI (per kg/m2) | |||||||||

| 2 years (n = 1106) | −0.0031 | (−0.0057,-0.0004) | 0.02 | −0.0023 | (−0.0051,0.0005) | 0.1 | −0.0022 | (−0.0050,0.0006) | 0.1 |

| 4 years (n = 1256) | −0.0007 | (−0.0037,0.0023) | 0.7 | −0.0002 | (−0.0033,0.0028) | 0.9 | −0.0001 | (−0.0032,0.0030) | 0.9 |

| 6 years (n = 1176) | 0.0009 | (−0.0028,0.0045) | 0.7 | 0.0016 | (−0.0021,0.0054) | 0.4 | 0.0002 | (−0.0036,0.0040) | 0.9 |

| 7 years (n = 1217) | 0.0019 | (−0.0016,0.0053) | 0.3 | 0.0024 | (−0.0011,0.0060) | 0.2 | 0.0008 | (−0.0028,0.0043) | 0.7 |

| 11 years (n = 1219) | 0.0031 | (0.0009,0.0053) | 0.006 | 0.0033 | (0.0011,0.0055) | 0.004 | 0.0012 | (−0.0012,0.0036) | 0.3 |

| 15 years (n = 1134) | 0.0023 | (0.0003,0.0042) | 0.06 | 0.0024 | (0.0004,0.0044) | 0.02 | 0.0001 | (−0.0021,0.0022) | 0.96 |

| 20 years (n = 1185) | 0.0009 | (−0.0010,0.0028) | 0.4 | 0.0010 | (−0.0009,0.0029) | 0.3 | −0.0011 | (−0.0032,0.0011) | 0.3 |

| Height (per cm) | |||||||||

| 2 years (n = 1151) | −0.0005 | (−0.0019,0.0008) | 0.4 | −0.0001 | (−0.0015,0.0015) | 0.9 | 0.0003 | (−0.0013,0.0018) | 0.7 |

| 4 years (n = 1256) | −0.0007 | (−0.0022,0.0008) | 0.8 | 0.0001 | (−0.0010,0.0012) | 0.8 | 0.0014 | (0.0001,0.0026) | 0.04 |

| 6 years (n = 1176) | −0.0002 | (−0.0011,0.0005) | 0.8 | 0.0001 | (−0.009,0.0012) | 0.8 | 0.0012 | (−0.0002,0.0025) | 0.08 |

| 7 years (n = 1217) | −0.0002 | (−0.0011,0.0007) | 0.7 | −0.0002 | (−0.0011,0.0007) | 0.7 | 0.0015 | (0.0002,0.0027) | 0.02 |

| 11 years (n = 1219) | −0.0003 | (−0.0012,0.0007) | 0.6 | −0.0005 | (−0.0013,0.0003) | 0.7 | 0.0003 | (−0.0007,0.0013) | 0.5 |

| 15 years (n = 1134) | −0.0006 | (−0.0012,0.0001) | 0.1 | −0.0005 | (−0.0012,0.0002) | 0.2 | 0.0003 | (−0.0007,0.0013) | 0.5 |

| 20 years (n = 1185) | −0.0007 | (−0.0015,0.0001) | 0.06 | −0.0007 | (−0.0015,0.0001) | 0.1 | 0.0008 | (−0.0011,0.0027) | 0.4 |

BMI and height at each age

BMI and height at every age were positively associated with LVM (Table 2) and LVEDV (Table 3), with suggestion of non-linear relationships with BMI at age 4. There was little confounding by birthweight or life course SEP (Tables 2 and 3). Weaker and less consistent associations were observed with RWT (Table 4). Increasing BMI at age 2 was associated with decreasing RWT, whereas increasing BMI at ages 11 and 15 was associated with increasing RWT (Table 4). The association with BMI at age 2 was somewhat reduced on addition of the confounding variables, with additional investigation suggesting that there was confounding by birthweight.

Associations of early life BMI with LVM and LVEDV were attenuated after adjustment for current BMI and height, although positive associations remained for LVEDV at most ages (Tables 2 and 3). Consistent with this are the associations observed between BMI at each age and LVEDV indexed to either BSA or to height27 (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Data). BMI at most ages was, however, also positively (or non-linearly) associated with LVMI. The method of indexation had a much greater influence on associations with height than with BMI, probably because the associations between height and LV structure are a reflection of adult height (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Data). For RWT, the negative association with BMI at 2 years was not affected, but the positive associations with adolescent BMI were considerably reduced after adjustment for current BMI and height (Table 4). Associations with childhood and adolescent height were entirely explained by adult height.

Conditional BMI and height change

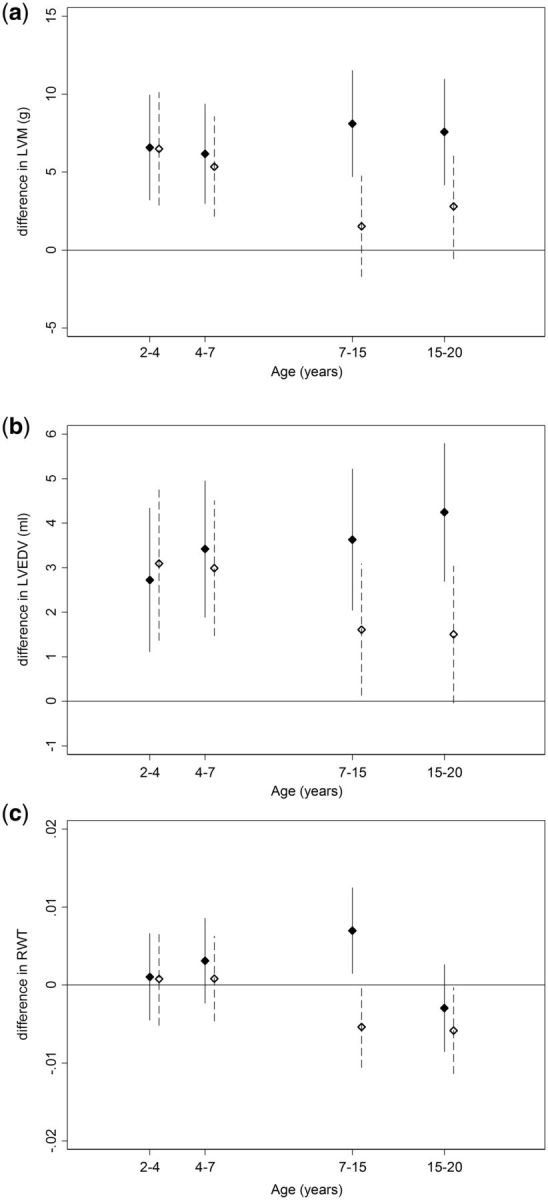

Greater conditional BMI gains during all four age periods considered were associated with higher LVM and LVEDV, with all periods of growth having similar relationships. These associations were only slightly, if at all, attenuated after adjustment for confounders (Figure 1a, b; Supplementary Data, available as Supplementary Data at IJE online). Positive associations with LVMI and LVEDVI were substantially weaker for all periods of change, with BMI change from 7–15 years being stronger than earlier periods of change for LVMI, and change from 15–20 years showing the strongest association with LVEDVI when indexed to BSA (Supplementary Data, available as Supplementary Data at IJE online). Faster height growth during each time period, particularly in the early periods, was associated with higher LVM and LVEVD before and after adjustment for confounders (Figure 1a, b; Supplementary Data). Height growth was not associated with LVMI or LVEDVI when indexed to BSA (Supplementary Data). Higher BMI gain during the pubertal period of 7–15 years was associated with higher RWT (Figure 1c). Higher systolic BP, diastolic BP and doctor-diagnosed type 2 diabetes were associated with higher LVM, LVEDV and RWT, and associations were slightly attenuated after adjustment for these CV risk factors (Supplementary Data).

Figure 1.

Conditional change (per standard deviation) in BMI (solid) and height (dash) for ages 2–4, 4–7, 7–15 and 15–20 years in relation to a) left ventricular mass (LVM), b) left ventricular end diastolic volume (LVEDV) c) relative wall thickness (RWT). Models adjusted for sex, birthweight, childhood and adult social class. Points are means, vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Accumulation of overweight

The more periods during childhood and adolescence that an individual had been overweight, the greater the LVM and LVEDV (Table 5). The association with LVM was attenuated slightly when possible confounders were included and was reduced further towards the null when current overweight and height were added to the model. Associations with LVEDV, although attenuated by adjustment, were not entirely explained (Table 5). These differences were consistent with the findings for outcomes indexed to BSA where an association is seen with LVEDVI but not with LVMI (Supplementary Data, available as Supplementary Data at IJE online). Additional analyses showed that CV risk factors also attenuated the association with LVM, but less so for LVEDV.

Table 5.

Mean difference (and 95% confidence interval) in left ventricular mass (LVM), left ventricular end diastolic volume (LVEDV) and relative wall thickness (RWT) by length of childhood and adolescent overweight: models adjusted for sex only (model 1); sex and confounders (model 2); sex, confounders and overweight and height at 60–64 years (model 3)

| Adjusted for sex (model 1) |

Model 1 +additionally adjusted for childhood and adult social class and birthweight (model 2) |

Model 2 + additionally adjusted for overweight and height at 60–64 years (model 3) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient (95% CI) | P-value trend | Regression coefficient (95% CI) | P-value trend | Regression coefficient (95% CI) | P-value trend | |

| LVM (g) (n = 944) | ||||||

| Number of times overweight | ||||||

| 0 (n = 670) | Reference | 0.02 | Reference | 0.07 | Reference | 0.2 |

| 1 (n = 201) | 3.0 (−5.2,11.1) | 1.3 (−6.9,9.5) | 1.4 (−6.3,9.2) | |||

| 2 (n = 61) | 11.5 (−2.2,24.9) | 8.8 (−4.8,22.4) | 4.7 (−8.2,17.5) | |||

| 3 (n = 12) | 31.9 (2.4,61.4) | 28.9 (−0.5,58.4) | 21.1 (−6.8,48.9) | |||

| LVEDV (ml) (n = 995) | ||||||

| Number of times overweight | ||||||

| 0 (n = 703) | Reference | < 0.001 | Reference | < 0.001 | Reference | 0.001 |

| 1 (n = 212) | 4.5 (0.6,8.3) | 4.3 (0.4,8.2) | 4.2 (0.4,7.9) | |||

| 2 (n = 67) | 10.0 (3.7,16.2) | 9.7 (3.4,16.0) | 8.5 (2.5,14.6) | |||

| 3 (n = 13) | 12.3 (−1.5,26.0) | 11.8 (−1.9,25.6) | 10.2 (−3.1,23.4) | |||

| RWT (n = 944) | ||||||

| Number of times overweight | ||||||

| 0 (n = 670) | Reference | 0.3 | Reference | 0.4 | Reference | 0.2 |

| 1 (n = 201) | −0.007 (−0.020,0.007) | −0.006 (−0.020,0.007) | −0.008 (−0.022,0.006) | |||

| 2 (n = 61) | −0.007 (−0.029,0.016) | −0.006 (−0.029,0.016) | −0.010 (−0.033,0.012) | |||

| 3 (n = 12) | −0.010 (−0.058,0.039) | −0.009 (−0.057,0.040) | −0.015 (−0.063,0.034) | |||

LV remodelling

Birthweight was not associated with LV remodelling category. Higher BMI from 6 years onwards was associated with greater odds of concentric LVH compared with normal (Supplementary Data, available as Supplementary Data at IJE online). A similar pattern of association, although much weaker, was observed for eccentric LVH whereas no associations with BMI were apparent for concentric remodelling. Change in BMI from ages 7 to 15 was most strongly associated with LV remodelling, and in particular concentric LVH (Supplementary Data, available as Supplementary Data at IJE online).

Discussion

In this nationally representative cohort study with over 60 years of follow-up, birthweight was positively associated with LVM and LVEDV at age 60–64, with evidence of a levelling off or decline in the association at higher birthweights for LVM. These associations were explained by adult height. Associations between early life body size and LVM and LVEDV were broadly similar; higher BMI and taller height at all ages, greater changes in BMI and height and a greater accumulation of overweight were associated with higher values. Some of these associations, more notably for LVM, were mediated through adult BMI. All associations with height in childhood were accounted for by adult height. There were less consistent and weaker associations with RWT.

A major strength of the study is the availability of multiple measurements of height and weight throughout childhood and adolescence, together with the standardized measures of cardiac structure using echocardiography in a relatively large sample of people in early old age. This provides a unique opportunity to investigate the relative strengths of associations with BMI at different ages and changes in body size.

The NSHD is representative of the British-born population in 1946, and therefore we are unable to study ethnic differences or to generalize our findings beyond the White British population of similar age. Those included in the analysis were taller and had lower BMI at 60–64 than those who provided data at 60–64 but were not included in the analysis, largely those who had a home visit instead of a clinic visit. Previous analysis shows that those attending clinic were healthier than those who had a home visit, and thus the analysis sample is likely to be healthier than the general population.23 Given the healthier characteristics of the sample and the low levels of childhood overweight and obesity in NSHD, associations with BMI might, if anything, be underestimated in our analyses. BMI was the only measure of adiposity available in childhood; nevertheless. although it does not measure fat mass directly, it has been shown to be a reasonable measure of adiposity in childhood.26(26)

Modelling growth in relation to a subsequent health outcome is challenging.27–29 In the NSHD, heights and weights were measured at fixed ages and were relatively widely spaced. We thus used a conditional change approach, as there is little or nothing to be gained from more complex modelling of the growth trajectory which is more beneficial with age-heterogeneous measurements.30 The conditional change model can be interpreted as the change in body size above or below that expected given earlier BMI or height, and is useful in identifying accelerated or restricted growth.29 LV size is known to scale in proportion to body size but the appropriate mode of indexation remains contentious; indexing LVM to BSA underestimates LVH among those who are obese.31,32 In our primary analyses, we therefore chose not to index LV mass but to include height and BMI as covariates in models, thereby avoiding potential problems with age-related differences in optimal scaling index. However, sensitivity analyses using indexed values supported the conclusions of the primary analyses.

Our findings for birthweight are in contrast to previous studies, which have generally found no association between birthweight and LVM. Our study contains a larger sample size and thus has greater statistical power than most previous studies, particularly to detect a possible non-linear association. That the birthweight association was largely explained by adult height suggests that associations reflect allometric scaling of LV size to body size.33 Prematurity may be a more important risk factor for LVH than birthweight, as a recent study has shown increased LVM and remodelling of the hearts of adults who were born preterm (gestational age 30.3 ± 2.5 weeks; birthweight 1297 ± 287 g).13 Gestational age was not available in the NSHD and thus we could not investigate this. However, in 1946, few premature babies would have survived34 and thus the observed association with birthweight is unlikely to represent, or be confounded by, gestational age. Younger cohorts are thus required, to disentangle the effects of gestational age and birthweight. Previous studies have observed a negative association between higher weight in early postnatal life and lower LVM in adulthood11,12 rather than lower RWT, as in the current study. The association between high BMI at age 2 and lower RWT is a result of the stronger positive relationship between BMI at that age and LVEDV compared with LVM. Infant weight gain may have a different impact on overall LV structure compared with later childhood and adolescent BMI change.

For LVM and particularly for LVEDV, our evidence suggests that high BMI from early childhood onwards has consequences for LV structure in later life. Consistent with our findings, those from the Bogalusa Heart Study suggested that higher childhood BMI was associated with higher LVMI in young adulthood.14 However, that sample was age-heterogeneous, meaning that the measure of childhood BMI used was recorded at ages varying from 4 to 17 years. Consequently, it was not possible to determine whether BMI at all ages was similarly associated with LVMI. For LVM, LVEDV and their indexed values, we showed consistent associations with BMI across childhood and adolescence. More rapid changes in BMI at all ages were positively associated with LVM and LVEDV without evidence of there being a sensitive period in which gain in BMI is particularly detrimental. The most recent of two reports on LV remodelling in the Bogalusa Heart Study showed that a greater cumulative exposure to higher BMI (using the area under the curve for individual study members) was related to higher LVMI and greater odds of LVH.16 This is consistent with our findings, namely that the greater the duration of overweight in childhood and adolescence, the higher the LVM and LVEDV. For LVEDV this was seen even among those currently not overweight and was independent of CV risk factors. For LVM, the association was largely explained by adult height and BMI. The fact that associations were observed between higher BMI in childhood and higher LVM indexed to BSA might suggest mediation through adult adiposity rather than the associations simply reflecting general adult body size.

Studies in childhood and adolescence show that high BMI and overweight are associated with higher LVM.6 A systematic review of cross-sectional studies in children found that those who were obese had an LVM on average 19.12 (12.66,25.59)g greater than children of normal weight.35 The increased LVEDV in those with accumulated exposure to overweight is interpretable as an indicator of elevated preload, and this is consistent with evidence of enhanced recruitment of preload reserve in obesity.36 Our findings for LVM are consistent with studies which suggest that some reversal of elevated LVM is possible with weight loss.37,38 However, it is uncertain whether complete reversibility can be achieved, particularly following more severe overweight or obesity. We showed only weak evidence that associations may explained by adult BP, heart rate and type 2 diabetes. In this cohort, faster rises in midlife BP, as well as contemporaneous BP, are associated with detriments to LV structure and diastolic function.39,40 Childhood overweight is associated with increased levels of CV risk factors such as BP, total cholesterol and glucose in childhood.35 Therefore cumulative exposure to higher BP and other CV risk factors, which the current measures do not reflect, may be one pathway through which accumulation of high BMI from childhood is associated with high LVM and LVEDV in older age.

For the most part, changes in LVM and LVEDV linked with BMI occurred without much effect on RWT. The exception was the stronger effect of pubertal BMI gain and the similar finding that rapid BMI gain from ages 7 to 15 was most strongly related to concentric hypertrophy characterized by an increased RWT and increased LVM. Few studies have investigated the associations of childhood body size with RWT or LVEDV. A small Australian study with echocardiography in young adulthood41 showed that childhood overweight was not related with RWT.

Tracking of body size from childhood to adulthood means that it is difficult to disentangle the impact of early life body size from current body size.42 Adjustment for adult body size in the analyses makes strong assumptions43 which, if they do not hold, may bias the findings. Height growth in childhood does not appear to have an association with later life LV structure over and above that of adult height, and thus is likely to reflect LV scaling to normal somatic growth. Given that in the NSHD cohort fewer children were overweight or obese compared with more contemporary cohorts,44 we might expect associations between childhood BMI and accumulation of overweight with LV structure to be stronger, and of greater public health importance in later-born generations. Even if childhood and adolescent overweight or obesity does not have a large direct effect on later life LV structure, there is an indirect effect through the tracking of BMI from childhood through to adulthood.

Conclusions

High BMI and overweight across childhood and adolescence and accumulation of overweight across the life course was associated with greater LVM and LVEDV. These associations, particularly those with LVM, were partially mediated by adult body size. These findings are of particular public health relevance given the increasing levels of overweight in contemporary cohorts of children and emphasises the need for effective interventions to reduce childhood overweight.

Funding

This work is supported by the UK Medical Research Council which provides core funding for the MRC National Survey of Health and Development and R.H. and D.K. [MC_UU_12019/1,MC_UU_12019/2]. A.D.H. and J.E.D. received support from the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to NSHD study members who took part in the clinic data collection for their continuing support. We thank members of the NSHD scientific and data collection teams at the following centres: MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at UCL; Wellcome Trust (WT) Clinical Research Facility (CRF) Manchester; WTCRF and Medical Physics at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh; WTCRF and Department of Nuclear Medicine at University Hospital Birmingham; WTCRF and the Department of Nuclear Medicine at University College London Hospital; CRF and the Department of Medical Physics at the University Hospital of Wales; CRF and Twin Research Unit at St Thomas’ Hospital London. Data used in this publication are available upon request to the MRC National Survey of Health and Development Data Sharing Committee. Further details can be found at http://www.nshd.mrc.ac.uk/data. doi: 10.5522/NSHD/Q101; doi: 10.5522/NSHD/Q102; doi: 10.5522/NSHD/S102D.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1561–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schieken RM, Schwartz PF, Goble MM. Tracking of left ventricular mass in children: race and sex comparisons–the MCV Twin Study: Medical College of Virginia. Circulation 1998;97:1901–06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dekkers C, Treiber FA, Kapuku G, Van Den Oord EJ, Snieder H. Growth of left ventricular mass in African American and European American youth. Hypertension 2002;39:943–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sivanandam S, Sinaiko AR, Jacobs DR, Steffen LM, Moran A, Steinberger J. Relation of increase in adiposity to increase in left ventricular mass from childhood to young adulthood. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:411–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Urbina EM, Gidding SS, Bao W, Pickoff AS, Berdusis K, Berensen GS. Effect of body size, ponderosity, and blood pressure on left ventricular growth in children and young adults in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Circulation 1995;91:2400–06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Jonge LL, van Osch-Gevers L, Willemsen SP, et al. Growth, obesity, and cardiac structure in early childhood: the Generation R Study. Hypertension 2011;57:934–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Geelhoad JJ, Steegers EA, van Osch-Gevers L, et al. Cardiac structures track during the first 2 years of life and are associated with fetal growth and hemodynamics: the Generation R Study. Am Heart J 2009;158:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiang B, Godfrey KM, Martyn CN, Gale CR. Birthweight and cardiac structure in children. Pediatrics 2006;117:e257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hietalampi H, Pahkala K, Jokinen E, et al. Left ventricular mass and geometry in adolescence: early childhood determinants. Hypertension 2012;60:1266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumaran K, Fall CH, Martyn CN, Vijayakumar M, Stein C, Shier R. Blood pressure, arterial compliance, and left ventricular mass: no relation to small size at birth in south Indian adults. Heart 2000;83:272–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vijayakumar M, Fall CH, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Birthweight, weight at one year, and left ventricular mass in adult life. Br Heart J 1995;73:363–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zureik M, Bonithon-Kopp C, Lecomte E, Siest G, Ducimetirere P. Weights at birth and in early infancy, systolic pressure, and left ventricular structure in subjects aged 8 to 24 years. Hypertension 1996;27:339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lewandowski AJ, Augustine D, Lamata P, et al. Preterm heart in adult life: cardiovascular magnetic resonance reveals distinct differences in left ventricular mass, geometry, and function. Circulation 2013;127:197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li X, Li S, Ulusoy E, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Berensen GS. Childhood adiposity as a predictor of cardiac mass in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Circulation 2004;110:3488–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Toprak A, Wang H, Chen W, Paul T, Srinivasan S, Berensen G. Relation of childhood risk factors to left ventricular hypertrophy (eccentric or concentric) in relatively young adulthood (from the Bogalusa Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2008;101:1621–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lai C-C, Sun D, Cen R, et al. Impact of long-term burden of excessive adiposity and elevated blood pressure from childhood on adulthood left ventricular remodeling patterns. The Bogalusa Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:1580–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reis JP, Allen N, Gibbs BB, et al. Association of the degree of adiposity and duration of obesity with measures of cardiac structure and function: The CARDIA study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:2434–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lorber R, Gidding SS, Daviglus ML, Colangelo LA, Liu K, Gardin JM. Influence of systolic blood pressure and body mass index on left ventricular structure in healthy African-American and white young adults: the CARDIA study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:955–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wadsworth MEJ, Hardy R, Paul AA, Marshall SF, Cole TJ. Leg and trunk length at 43 years in relation to childhood health, diet and family circumstances; evidence from the 1946 national birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paajanen TA, Oksala NK, Kuukasjarvi P, Karhunen PJ. Short stature is associated with coronary heart disease: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1802–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wadsworth MEJ, Butterworth SL, Hardy RJ, et al. The life course prospective design: an example of benefits and problems of study longevity. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:2193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuh D, Pierce M, Deanfield J, et al. Cohort Profile: Updating the cohort profile for the MRC National Survey of Health and Development: a new clinic-based data collection for ageing research. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stafford M, Black S, Shah I, et al. Using a birth cohort to study ageing: representativeness and response rates in the National Survey of Health and Development. Eur J Ageing 2013;10:145–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiol 2005;18:1440–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dietz WH, Robinson TN. Use of the body mass index as a measure of overweight in children and adolescents. J Pediatrics 1998;132:191–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Stavola B, Nitsch D, dos Santos Silva I, et al. Statistical issues in life course epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tu Y-K, Tilling K, Sterne JA, Gilthorpe MS. A critical evaluation of statistical approaches to examining the role of growth in the developmental origins of health and disease. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1327–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wills AK, Silverwood RJ, De Stavola BL. Comment on Tu et al. 2013. A critical evaluation of statistical approaches to examining the role of growth trajectories in the developmental origins of health and disease. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1662–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wills A, Tilling K. Modelling repeat exposures: some examples from life course epidemiology. In: Kuh D, Cooper R, Hardy R, Richards M, Ben-Shlomo Y. (eds). A Life Course Approach to Healthy Ageing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Armstrong AC, Gidding S, Gjesdal O, Wu C, Bluemke DA, Lima JA. LV mass assessed by echocardiography and CMR, cardiovascular outcomes, and medical practice. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;5:837–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pfaffenberger S, Bartko P, Graf A, et al. Size matters! Impact of age, sex, height, and weight on the normal heart size. Circulation 2013;6:1073–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dewey FE, Rosenthal D, Murphy DJ, Froelicher VF, Ashley EA. Does size matter?: Clinical applications of scaling cardiac size and function for body size. Circulation 2008;117:2279–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Iacovidou N, Varsami M, Syggellou A. Neonatal outcome of preterm delivery. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1205:130–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Friedemann C, Heneghan C, Mahtani K, Thompson M, Perera R, Ward AM. Cardiovascular disease risk in healthy children and its association with body mass index: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;345:e4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vasan RS. Cardiac function and obesity. Heart 2003;89:1127–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karason K, Wallentin I, Larsson B, Sjostrom L. Effects of obesity and weight loss on left ventricular mass and relative wall thickness: survey and intervention. BMJ 1997;315:912–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haufe S, Utz W, Engeli S, et al. Left ventricular mass and function with reduced-fat or reduced-carbohydrate hypocaloric diets in overweight and obese subjects. Hypertension 2012;59:70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ghosh AK, Hardy RJ, Francis DP, et al. ; Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development (NHSD) Scientific and Data Collection Team. Midlife blood pressure change and left ventricular mass and remodelling in older age in the 1946 British Birth Cohort Study. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3287–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ghosh AK, Hughes AD, Francis D, et al. ; MRC NSHD Scientific and Data Collection Team. Midlife blood pressure predicts future diastolic dysfunction independently of blood pressure. Heart 2016, April 7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015–308836. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tapp RJ, Venn A, Huynh QL, et al. Impact of adiposity on cardiac structure in adult life: the childhood determinants of adult health (CDAH) study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2014;14:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wills AK, Hardy RJ, Black S, Kuh DJ. Trajectories of overweight and body mass index in adulthood and blood pressure at age 53: the 1946 British birth cohort study. J Hypertens 2010;28:679–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. De Stavola BL, Daniel RM, Ploubidis GB, Micali N. Mediation analysis with intermediate confounding: structural equation modeling viewed through the causal inference lens. Am J Epidemiol 2015;181:64–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Johnson W, Li L, Kuh D, Hardy R. How has the age-related process of oveweight or obesity devlopment changed over time? Co-ordinated analysis of individual participant data from five United Kingdom birth cohorts. PLOS Med 2015;12:e1001828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.