OsFBK1 mediates the turnover of OsCCR14 via the 26S proteasome pathway, resulting in changes in secondary cell wall content in anthers and roots, without changes in auxin signaling.

Abstract

Regulated proteolysis by the ubiquitin-26S proteasome system challenges transcription and phosphorylation in magnitude and is one of the most important regulatory mechanisms in plants. This article describes the characterization of a rice (Oryza sativa) auxin-responsive Kelch-domain-containing F-box protein, OsFBK1, found to be a component of an SCF E3 ligase by interaction studies in yeast. Rice transgenics of OsFBK1 displayed variations in anther and root secondary cell wall content; it could be corroborated by electron/confocal microscopy and lignification studies, with no apparent changes in auxin content/signaling pathway. The presence of U-shaped secondary wall thickenings (or lignin) in the anthers were remarkably less pronounced in plants overexpressing OsFBK1 as compared to wild-type and knockdown transgenics. The roots of the transgenics also displayed differential accumulation of lignin. Yeast two-hybrid anther library screening identified an OsCCR that is a homolog of the well-studied Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) IRX4; OsFBK1-OsCCR interaction was confirmed by fluorescence and immunoprecipitation studies. Degradation of OsCCR mediated by SCFOsFBK1 and the 26S proteasome pathway was validated by cell-free experiments in the absence of auxin, indicating that the phenotype observed is due to the direct interaction between OsFBK1 and OsCCR. Interestingly, the OsCCR knockdown transgenics also displayed a decrease in root and anther lignin depositions, suggesting that OsFBK1 plays a role in the development of rice anthers and roots by regulating the cellular levels of a key enzyme controlling lignification.

The mechanism of anther dehiscence has been largely studied in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), where a number of key players involved in the process and their regulation has been described (Yang et al., 2007; Song et al., 2011). However, anther dehiscence in rice (Oryza sativa) was paid little attention until recent years, even though pollination is an irrefutable process for the fructification of grain crops. Poor dehiscence of anthers has been a causative factor for depleting yield of grain crops and, moreover, the mechanism of dehiscence is highly prone to temperature stress in rice (Matsui et al., 1999).

Toward the end of anther maturation, the degeneration of the middle layer and tapetum signals the lignification of the cellulosic microfibrils in the endothecial cell walls (Dawson et al., 1999). The presence of U-shaped cell wall lignified thickenings in the apical and basal parts of the locules is instrumental in anther dehiscence. The process of thickening is triggered by the increasing levels of auxin and the activation of auxin responsive genes (Cecchetti et al., 2008, 2013). The mechanism of anther dehiscence in rice has been described in great detail earlier (Matsui et al., 1999); at the onset of anthesis, pollen grains swell rapidly in response to the opening of the floret, causing the theca to bulge under the increasing pressure of the pollens. During this stage, the inward buckling of the locule walls adjacent to the stomium accompanied by the pollen pressure causes the stomium to split at the apical portion of each theca. Similarly, in the large locules, the split in the septum runs along the longitudinal line to the bottom. Due to the uneven distribution of wall thickenings and subsequent dehydration of these structures, the locule walls adjacent to the splits straighten and widen the openings in the apical and basal parts of the anther. This full opening of the stomium allows the pollen grains to overflow and cause pollination. The splitting of the stomium and pollen maturation have been found to be under the influence of jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis (Sanders et al., 2000; Ishiguro et al., 2001).

In Arabidopsis, mutant studies have demonstrated the presence of multiple factors regulating the anther dehiscence pathway such as transcription factors MYB26/MALE STERILE35, MYB21, MYB24 (Yang et al., 2007; Song et al., 2011), and F-box proteins RMF (Kim et al., 2010) and SAF1 (Kim et al., 2012), to name a few. In rice, a few genes encoding proteins like ANTHER INDEHISCENCE1 (Zhu et al., 2004), PSS1 kinesin1-like protein (Zhou et al., 2011), SIZ1 SUMO E3 ligase (Thangasamy et al., 2011), OsJAR1 (Xiao et al., 2014), and F-box protein ADF (Li et al., 2015) have been studied for their roles in controlling anther development and dehiscence. F-box proteins (FBPs), as part of the SCF E3 ligase, have an important role to play in the identification and preparation of target proteins poised for degradation via the ubiquitin-26S proteasome pathway (Vierstra, 2009). In recent years, since the studies on FBPs gained momentum in different plant species (Jain et al., 2007; Hua et al., 2011), myriad functions have been attributed to this superfamily of proteins, including hormone perception and synthesis (McGinnis et al., 2003; Ariizumi et al., 2011), control of plant morphogenesis (Samach et al., 1999; Sawa et al., 2007), roles in self-incompatibility and host-pathogen interaction (Kim and Delaney, 2002; Hua and Vierstra, 2011), among others. Since FBPs comprise one of the largest gene families in all plant genome examined (McGinnis et al., 2003), many more diverse roles are likely to be unraveled as the work advances on their functional characterization.

In this study, we have identified and characterized a Kelch domain containing FBP, OsFBK1, that is a part of a putative SCFOsFBK1 E3 ligase, and have elucidated the role it plays in regulating levels of endothecium U-shaped thickenings in the anther cell wall by controlling the cellular levels of one of the key enzymes involved in the lignification processes in plants. In a preliminary study, we have also shown that rice transgenics with altered OsFBK1 expression exhibit drought tolerance (Borah et al., 2017).

RESULTS

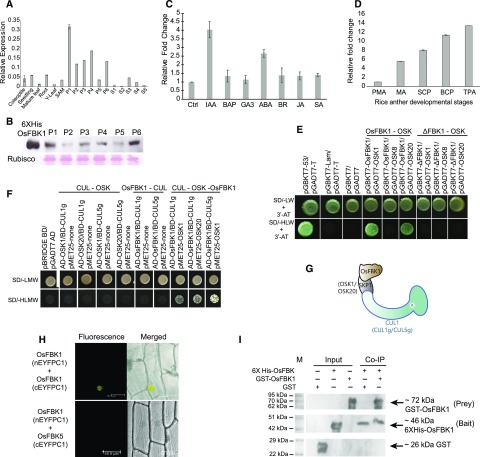

Expression and Structural Analyses of OsFBK1

The gene OsFBK1 (Oryza sativa F-box Kelch 1, LOC_Os01g47050) was identified in an earlier study in our laboratory (Jain et al., 2007), wherein comprehensive phylogenetic analysis and microarray-based genome-wide expression profiling of FBP coding genes in rice was carried out. This gene was found to express during various stages of panicle development with a comparatively higher expression in the early stages as well as in root tissues of 7-d-old seedlings of IR64 variety of rice. The microarray data were verified by qPCR analysis in all the stages analyzed earlier (Jain et al., 2007) using Pusa Basmati1 (PB1; Fig. 1A) since it is more amenable for transformation work. Antibodies raised against the whole protein were used to determine the protein profile of OsFBK1 in the rice tissues corresponding to various panicle stages (P1 to P6; Fig. 1B). Its response to various hormones was also examined by qPCR (Fig. 1C). OsFBK1 transcript levels were higher in the seedlings treated with indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and abscisic acid (ABA) as compared to the other hormones. The expression of OsFBK1 was further checked in the available Rice Atlas Database (GSE13988, GSE14298, GSE14299, and GSE14300) using the Rice Oligonucleotide Array Database and was found to have high transcript abundance in the late anther developmental stages also (bicellular pollen stage, equivalent to anther P2; Fujita et al., 2010; data not shown). The microarray data were confirmed by real-time PCR analyses using anther tissues of different developmental stages (Fig. 1D), where the transcripts accumulated in increasing order of anther development (see Fig. 1D legend). The response of OsFBK1 to abiotic stresses was also explored in our laboratory. In a rice cultivar, IR20, that is susceptible to drought, the expression of OsFBK1 was enhanced considerably in young seedlings exposed to drought stress and on treatment with ABA (Borah et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Expression profile of OsFBK1 and structural analysis. A, OsFBK1 expression as quantitated by real-time PCR analysis in vegetative (coleoptile, mature leaf, root, and shoot apical meristem), panicle, and seed stages of development in IR64 (P1, 0–3 cm; P2, 3–5 cm; P3, 5–10 cm; P4, 10–15 cm; P5, 15–22 cm; P6, 22–30 cm; S1, 0–2 days after pollination [dap]; S2, 3–4 dap; S3, 5–10 dap; S4, 11–20 dap; S5, 21 to 29 dap). Standard bars denote se. B, Western blot showing the levels of the protein in the different stages of panicle development. Bottom, equal loading of samples by the visualization of Rubisco after Ponceau staining of the membrane. C, Real-time PCR analysis of OsFBK1 in different hormone stresses. IAA, Indole-3-acetic acid; BAP, benzylaminopurine; GA3, gibberellic acid 3; ABA, abscisic acid; BR, epibrassinolide; JA, jasmonic acid; SA, salicylic acid. Error bars denote sd. D, qPCR of OsFBK1 in the anther development stages (PMA, premeiotic anther; MA, meiotic anther; SCP, single-cell pollen; BCP, bicellular pollen; TPA, tricellular pollen anther). Error bars denote sd. E, Y2H assay showing the interaction of OsFBK1 with OSKs. Positive control, pGBKT7-53/pGADT7-T; negative control, pGBKT7-Lam/pGADT7-T; vector control, pGBKT7/pGADT7. F, Modified Y2H assay demonstrating the three-way interactions of CULLIN, OSK, and OsFBK1 (lanes 8–10). Direct interaction between CULLIN and OSK (lanes 2–5) and CULLIN and OsFBK1 (lanes 6–7) was not visible. Y2H using pBRIDGE does not have standard controls. G, Graphical representation of a putative SCFOsFBK1 complex (minus RBX1). H, BiFC showing the presence of a homodimer in the nucleus of onion epidermal peel cells. Negative control, OsFBK1-OsFBK5 BiFC. I, Co-IP of OsFBK1 homodimerization. The second, third, and fourth lanes are the unpurified input bacterial extracts of GST, GST-OsFBK1, and 6XHis-OsFBK1, respectively. GST wash was used as a negative control for co-IP with 6XHis-OsFBK1 (lane five). GST-OsFBK1 was probed by rabbit anti-GST mAb, while 6XHis-OsFBK1 was detected by using mouse anti-His mAb. These blots were parallelly processed with the same samples. M, Marker lane. See also Supplemental Figures S1, S2, and S5.

To determine the structure of OsFBK1, ab initio modeling using the Robetta server (http://robetta.bakerlab.org/) was carried out. The predicted models were validated by Ramachandran plot analyses, and it was found that OsFBK1 contains a ligase domain (F-box domain and other adjoining sequences) at its N-terminal end and a protein-binding domain consisting of a 6-bladed Kelch β-propeller toward the C-terminal end (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Further, multiple sequence alignment of the F-box domain of OsFBK1 (aa positions 52–92) along with its closest orthologs across 31 species of monocots, dicots, and animals was carried out by using the MAFFT server (Katoh et al., 2002). The domain formed a tight group with monocots while sharing a strong homology to the canonical F-box sequence described previously in humans (Schulman et al., 2000; Supplemental Fig. S1B).

Since FBPs are part of the SCF complex, it was imperative to know whether OsFBK1 can interact with the other components of the SCF complex. Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) analysis was employed to see the interaction between OsFBK1 (bait) and three rice Skp1s; OSK1, OSK8, and OSK20 (prey), as these expressed ubiquitously in all the tissues of the rice plant (Kong et al., 2007). It was found that OsFBK1 interacted with OSK1 and OSK20, but not with OSK8 (Fig. 1E). At the same time, ΔFBK1 construct (bait) lacking the entire F-box domain was found to be incapable of interacting with the OSKs, confirming that OsFBK1 and Skp1 interaction takes place via the conserved F-box domain (Fig. 1E). To determine whether the OsFBK1-OSK1/20 complex can interact with Cullin component of the SCF E3 ligase, a modified yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) approach was employed. Two Cullin genes, designated CUL1g and CUL5g in our study, were cloned in MCS I of pBRIDGE bait vector with OSK1 and OSK20 cloned in MCS II of the vector, respectively, so that OSK forms a bridge between CUL and OsFBK1. Figure 1F clearly shows that OsFBK1-OSK1/20 can interact with CUL1g and CUL5g and form two SCF complexes (minus the Rbx1 component). The interactions among OsFBK1, OSK1/20, and CUL1g/5g proved that OsFBK1 is an integral part of a SCFOsFBK1 E3 ligase (Fig. 1G). The cellular localization studies revealed that OsFBK1 is distributed throughout the cell, including the nucleus (Supplemental Fig. S2).

FBPs are known to form both hetero- and homodimers resulting in various substrate-recognizing conformations. To check whether OsFBK1 homodimerizes, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay was performed. In the particle-bombarded onion-peel epidermal cells, the YFP fluorescence was detected in the nucleus with negligible detectable fluorescence in the rest of the cell (Fig. 1H); another OsFBK served as negative control for this BiFC assay. Dimerization of OsFBK1 was further confirmed by coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP; Fig. 1I; Supplemental Fig. S5A).

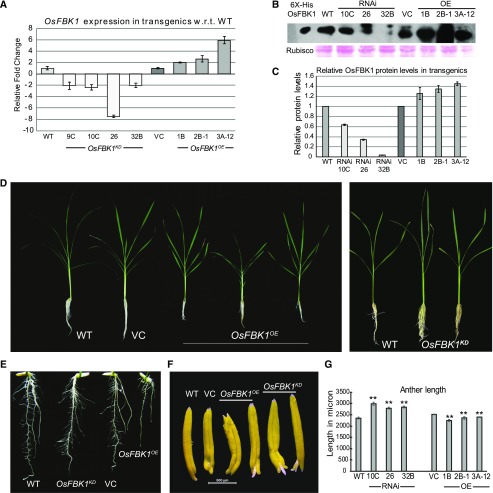

Rice Transgenics of OsFBK1 Display Distinct Morphological Changes

Transgenics of rice cultivar PB1 overexpressing OsFBK1 under the maize (Zea mays) ubiquitin promoter (OsFBK1OE), and those expressing RNAi construct (OsFBK1KD) were raised. Four independent OsFBK1OE lines were obtained and confirmed by Southern blotting (Supplemental Fig. S3A). The level of gene expression in the homozygous transgenic plants was checked by qPCR using root tissue (Fig. 2A), out of which three lines with elevated expression of OsFBK1 expression were selected for further analyses. The protein levels of OsFBK1 in these transgenics were also investigated by western blotting (Fig. 2B). While all three overexpression lines had elevated protein levels of OsFBK1 vis-à-vis wild type and vector control (VC), as corroborated by the real-time analysis, the RNAi lines demonstrated variations (albeit reduced than wild type) in the OsFBK1 protein levels as compared to wild type (Fig. 2C). Morphological changes observed in the OsFBK1 transgenics are shown in Supplemental Figure S3, B to H. However, the changes in morphology of anther and root in the OsFBK1 transgenics were distinct vis-à-vis wild type and VC and provided essential clues to narrow down the functions of this F-box protein (Fig. 2). A striking observation was made in the morphology of roots in the transgenics (Fig. 2, D and E). At 60 d postgermination, the root proliferation was more pronounced in the OsFBK1KD plants (Fig. 2D), whereas the length of roots of OsFBK1OE were reduced (with an apparent difference in root proliferation) as compared to wild-type and VC plants. This was also evident in the 7-d-old seedlings of OsFBK1KD, which displayed more numbers of lateral roots as compared to wild type and VC, while OsFBK1OE had the least number (Fig. 2E). On examining the length of the mature anthers of the controls and OsFBK1 transgenic lines, we observed that although the anthers of OsFBK1OE plants displayed >10% reduction in length as compared to wild-type and VC, the differences were marginal as they were within the normal range of mature anther length of 2.25 to 2.59 mm in rice (Raghavan, 1988). However, they were longer in the OsFBK1KD plants (Fig. 2, F and G), with an increase of ∼30% in anther length, which is well above the normal range. As anthers are known to continue their growth till the time of anthesis (Raghavan, 1988), the samples of each line were collected just before the onset of anthesis to prevent any discrepancies in sizes. As opposed to the anthers, the lemma, palea, and ovary tissues of OsFBK1OE were smaller in size, and changes in these organs of OsFBK1KD plants were not apparent (Supplemental Fig. S3E). These observations strongly indicated the role of OsFBK1 in the development of anther and roots. Interestingly, lateral root proliferation is known to be an auxin-mediated response (Overvoorde et al., 2010), and OsFBK1 expression was also found to be up-regulated on exposure to externally applied IAA, suggesting that auxin might influence the functions of this gene.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic and molecular analyses of OsFBK1 rice transgenics. A, Real-time PCR analysis of transgenic lines: OsFBK1OE (lines 1B, 2B-1, and 3A-12) and OsFBK1KD (lines RNAi 10C, 26, and 32B). B, Western-blot analysis of the protein levels of OsFBK1 in the transgenics using polyclonal antibodies against OsFBK1. C, Graphical representation of the band intensities of OsFBK1 protein levels in the transgenics, wild type, and VC. Error bars denote sd. D, Sixty-day-old plants of wild type and OsFBK1 transgenics showing differences in root growth. E, Roots of 7-d-old wild-type and transgenic seedlings. F, Morphological differences observed in the predehiscent anthers of OsFBK1 transgenics. Bar = 500 μm. G, Graphical representation of the lengths of the anthers of the transgenics wild-type (WT) and VC as measured by ImageJ software. Normal length of mature anthers, 2.25 to 2.59 mm. Error bars denote sd. VC, Vector control. Statistical significance (*P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.005) was calculated by ANOVA t test where wild type was the control for the OsFBK1KD lines and VC as control for OsFBK1OE plants. See also Supplemental Figure S3.

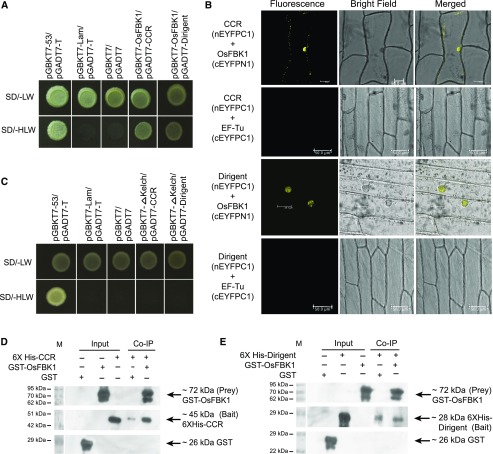

Identification of Interacting Factors/Putative Substrates of OsFBK1

For identifying the interacting partners/substrates of OsFBK1, screening of Y2H library made using anther tissues from late panicle stages P5 (15–22 cm) and P6 (22–30 cm) was undertaken. Of the six interacting partners identified (Supplemental Table S2), cinnamoyl coA reductase (CCR; LOC_Os08g34280) and dirigent (LOC_Os11g42500) were of particular interest. CCR is the first committing enzyme in lignin formation. Lignin, after cellulose, is the most naturally abundant and important biopolymeric substance in plant cell walls and provides rigidity to the plant structure (Weng and Chapple, 2010). On the other hand, the role of dirigent is mostly attributed to lignan (a large group of chemical compounds found in plants such as pinoresinol, podophyllotoxin, and steganacin) production, and its role in lignin formation is still debatable (Davin and Lewis, 2000, 2005; Weng and Chapple, 2010; Hosmani et al., 2013). The interactions between OsFBK1 and CCR/dirigent were verified by both Y2H screening and BiFC analyses (Fig. 3, A and B). Positive BiFC signals were observed in the nuclei of onion peel epidermal cells (Fig. 3B), with weak and punctuated cytoplasmic fluorescence for OsFBK1-CCR interaction and nondetectable fluorescence in the cytoplasm for interaction with dirigent. Negative control assays were carried out with an EF-Tu that has a similar cytoplasmic localization pattern to that of CCR (see Supplemental Fig. S7 for localization).

Figure 3.

Y2H library screening. A, Confirmation of OsFBK1 interactions with the identified partners by Y2H assay. B, BiFC analysis for the interacting partners and their location in the cell (OsFBK1 prey, CCR/Dirigent bait). Negative controls, CCR-EF-Tu BiFC and Dirigent-EF-Tu BiFC. C, Y2H interaction between ΔKelch and the protein partners of OsFBK1. D, OsFBK1-CCR co-IP. E, Pull-down of GST-OsFBK1 by 6XHis-tagged Dirigent. In both the co-IPs, crude GST wash was used as a negative control. The first three lanes are input westerns, while the last two lanes are co-IPs. The GST-tagged proteins were probed with rabbit anti-GST mAb, and the His-tagged proteins were detected by mouse anti-His mAb. These blots were parallelly processed with the same samples. M, Marker lane. See also Supplemental Figures S4, S5, and S7.

The Kelch β-propeller is known to be the substrate recognition domain of FBP. The blades of the propeller function as a rigid platform from where the loops containing the protein interacting residues emerge from the top (and narrower) surface of the propeller (Supplemental Fig. S1; Hudson and Cooley, 2008). Deletion of the blades and hence, any disruption in its structure, would affect the loop formation of the propeller, thereby diminishing the interactions between the F-box and its substrates. To test this hypothesis, the region from 290 to 338 amino acids of OsFBK1 was deleted (Supplemental Fig. S4A). The deleted protein (ΔKelch) was modeled by using the Robetta server, and it was evident from the model that one of the blades of OsFBK1 was removed and the overall structure of the β-propeller considerably disrupted (Supplemental Fig. S4B). When Y2H experiments using ΔKelch and CCR/dirigent were carried out, it was found that no positive colonies were visible, indicating that the deleted fragment of OsFBK1 was involved in interacting with the partner proteins (Fig. 3C). Finally, CCR and dirigent interactions with OsFBK1 were validated by co-IP experiments (Fig. 3, D and E; Supplemental Fig. S5, B and C).

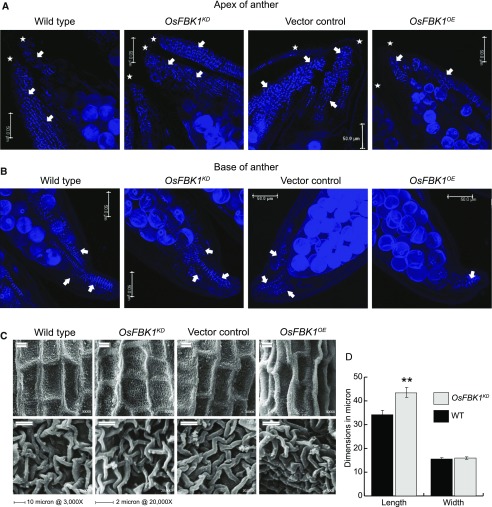

Rice CCR Is Orthologous to Arabidopsis CCR1 and OsFBK1 Transgenics Display Altered Anther Cell Wall Structure

In Arabidopsis, the irx class of mutants are known to exhibit various cell wall deformities, including collapse of the xylem vessels and loss of anther dehiscence (Turner and Somerville, 1997; Mitsuda et al., 2005). The irx4 mutant plants of Arabidopsis are lignin deficient and lack the functional CCR encoding gene, ATCCR1 (Jones et al., 2001). Until date two CCRs (ATCCR1 and ATCCR2) have been studied in detail in relation to their roles in lignification (Patten et al., 2005; Laskar et al., 2006; Ruel et al., 2009). The role of a CCR has also been established in defense signaling in rice (Kawasaki et al., 2006), and the authors had also identified a list of 26 putative OsCCR genes. However, in our study, we found that out of the 26 genes, six had duplicated locus IDs whereas four genes coded for dihydroflavonol-4-reductase (Supplemental Table S3). Further, by BLAST and reverse BLAST hits, we found four additional OsCCR genes, and all 21 genes were renamed alphabetically per their TIGR locus IDs (Supplemental Table S3). Thus, OsCCR1 characterized earlier (Kawasaki et al., 2006) has been redesignated as OsCCR5 in this study, while the CCR identified as interacting partner of OsFBK1 in our study was renamed OsCCR14 as opposed to OsCCR20 (Kawasaki et al., 2006) and will be henceforth referred to as OsCCR14 (Supplemental Table S3). Phylogenetic analysis to identify orthologs of ATCCR1/ATCCR2 in rice revealed that OsCCR14 and OsCCR18 formed a tight cluster with ATCCR1/IRX4 and ATCCR2 (Supplemental Fig. S6A). Thus, OsCCR14 is the rice ortholog of ATCCR1/IRX4 and bears a close sequence similarity with OsCCR18. OsCCR14 has been found to be localized throughout the cell, including the nucleus (Supplemental Fig. S7), and the cytoplasmic localization of OsCCR14 conforms to that reported earlier by Kawasaki et al. (2006). On the other hand, we could not find any close ortholog of the rice dirigent partner in Arabidopsis.

A detailed study on the cell wall ultrastructure of the Atccr1 mutant floral stems showed that they exhibited a reduction in their lignin content and a distinct disorganization of the lignified secondary walls accompanied with their loosening (Ruel et al., 2009). If OsCCR14 was indeed a substrate for OsFBK1, then its turnover mediated by OsFBK1 would result in the reduction of its protein levels in the OsFBK1OE plants, whereas in the OsFBK1KD transgenics the degradation of OsCCR14 should be less. The expression levels of OsCCR14 (Supplemental Fig. S6B) were also found to be higher in the late-anther developmental stages of the rice plant. Since lignification (formation of U-shaped thickenings concentrated at the apex and base of anthers) of the endothecium of anthers is an important prerequisite for dehiscence, the wall morphology of the anthers of transgenics was observed. Predehiscent anthers of OsFBK1 transgenics, wild type, and VC were cleared in 70% lactic acid and secondary wall thickenings (that fluoresce under UV) were observed in a confocal microscope (Fig. 4, A and B). The OsFBK1OE lines had a comparatively reduced amount of the U-shaped thickenings (highlighted by arrows) as compared to the others at both the apex (Fig. 4A) and base (Fig. 4B) of the locules (asterisk) of the anthers (see also Supplemental Fig. S8 for other lines). The OsFBK1KD lines appeared to have a slight increase in the lignified contents in their anthers. Scanning electron microscopy of the surface of the predehiscent anthers (3,000×) revealed the differences in the cell-surface morphology (Fig. 4C) of the transgenics vis-à-vis wild type and VC. The overall cell shape was preserved in the OsFBK1KD anthers and resembled those of wild type, except appearing slightly longer at 3,000× magnification (Fig. 4C, top). On the other hand, the OsFBK1OE anthers exhibited a disorganization of the cell wall boundaries, appearing puckered with a global collapsed structure. Even on higher magnification (20,000×), the ultrastructure of the cell walls of the OsFBK1OE anthers appeared to be more tightly packed (Fig. 4C, bottom). Interestingly, there were little negative effects on the dehiscent properties of the OsFBK1OE anthers, and these plants did not suffer from sterility issues, possibly due to the compensatory actions of OsCCR18 (except for line 1B, which exhibited reduced sterility probably due to high copy number of the transgene; Supplemental Fig. S3A). The measured cell wall dimensions of OsFBK1KD anthers (Fig. 4D) showed these were slightly longer than wild type while having no apparent changes in its breadth. These results strongly suggested that OsCCR14 could be a possible substrate of OsFBK1 and its turnover might affect regulation of secondary cell wall formation in rice anthers.

Figure 4.

Observation of anther wall morphology in transgenics. Confocal microscopy of cleared anther apices (A) and bases (B) of transgenics and wild-type (WT) showing the differences in the dispersal of the wall thickenings in the endothecium. The presence of the U-shaped thickenings is shown by arrows. Bar = 50 µm. Asterisk denotes separate locules in the same frame. The globular structures are pollen grains. C, Scanning electron microscopy images of the ridged anther cuticle of wild-type and transgenics at 3,000× (top) and at 20,000× (bottom) magnifications. D, Graphical representation of the dimensions of the anther surface cells as measured by using ImageJ software. Error bars denote se. Statistical significance has been calculated by ANOVA t test (**P ≤ 0.005). See also Supplemental Figure S8.

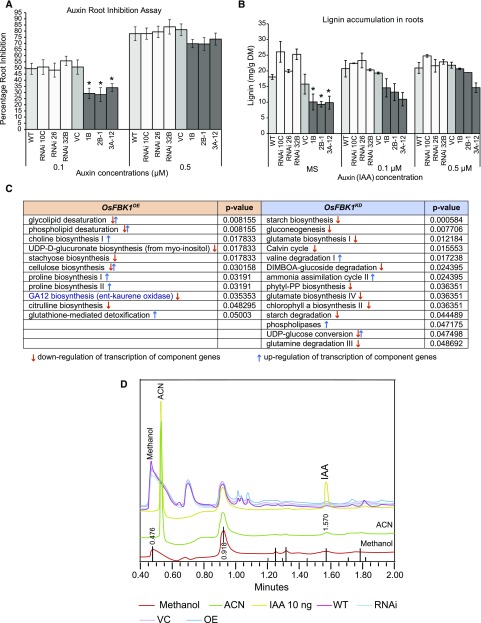

OsFBK1 and OsCCR14 Are Auxin-Responsive Genes and Regulate Lignification in Roots

In Arabidopsis, genes mediating cellulose remodeling are regulated by auxin (Osato et al., 2006). Both OsFBK1 and OsCCR14 have been found to have higher transcript abundance in roots of 7-d-old rice seedlings as well as when treated with auxin (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S6, B and C). Therefore, to determine whether OsFBK1 transgenics are altered in any way in their auxin sensitivity, 7-d-old seedlings of transgenics and wild type were subjected to auxin-mediated root inhibition assay (RIA) for 3 d (Fig. 5A). Standardization was done using a wide range of auxin concentrations, and we found that 0.1 and 0.5 µm IAA gave the best calculable results. As evident from Figure 5A, seedlings of OsFBK1OE lines were less sensitive to root inhibition (significantly at 0.1 µm IAA), while the sensitivities of the OsFBK1KD seedlings were comparable to wild type and VC. Secondary thickenings in roots can be assessed by the amount of lignin deposition in the cell walls; hence, the lignification of roots of OsFBK1 transgenics was also analyzed. The 7-d-old seedlings were grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with IAA (same as in case of root inhibition assay), and the roots were harvested after 7 d of treatment (maximum IAA exposure). Hypothetically, OsCCR14 being degraded by OsFBK1 would be unavailable for carrying out lignification in the roots of the OsFBK1OE plants, while in the OsFBK1KD lines the amount of lignin in the roots should be comparable to that of wild type and VC. As expected, when untreated the OsFBK1OE lines had the least amount of lignin content among the transgenics examined, whereas the untreated OsFBK1KD plants accumulated slightly more lignin than did wild type (Fig. 5B), clearly showing that the process of secondary cell wall thickenings of the roots is affected in the transgenics. However, as auxin concentration increased, the OsFBK1OE plants also started accumulating more lignin than in normal conditions, possibly as a response to the increasing inhibitory action of auxin against root growth (Sharma et al., 2015), and the activation of the other CCR genes already present in the plant’s repository to carry out secondary cell wall development for stress alleviation.

Figure 5.

Effect of externally applied auxin (IAA) on root growth in transgenics. A, Root inhibition assay using increasing concentrations of auxin. Error bars denote se. B, Quantification of lignin in the roots of 14-d-old seedlings exposed to auxin concentrations. DM, Dry mass. Error bars denote sd. C, Pathways highlighted in the roots of 14-d-old OsFBK1 transgenics seedlings after comparison with their respective controls. The P value cutoff was set at ≤0.05. D, UPLC profile of IAA in roots of 14-d-old seedlings of transgenics and controls. Auxin standard is 10 ng. Statistically significant differences were identified using ANOVA t test (*P ≤ 0.05), where wild type is the control for the RNAi lines and VC is the control for the overexpression lines.

Further, a question remains whether the changes in lignification in the transgenic lines reflect some indirect effect of altered auxin levels/signaling. To answer this query, microarray analyses of the roots of 14-d-old seedlings of transgenics and wild type were carried out. Pathway analysis of the differentially expressed genes revealed that the auxin signaling pathway was unaffected in the transgenics (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the GA12 biosynthesis pathway, especially the ent-kaurene oxidase gene was found to be down-regulated in the overexpression of transgenic plants (Fig. 5C). This could explain the partial stunting of the OsFBK1OE plants, but further experimentation is required to substantiate this observation. Auxin levels were also examined by UPLC (Fig. 5D) and it was found that there were no measurable differences in the transgenics and wild type, implying the possible turnover of OsCCR14 mediated by OsFBK1 controls lignification of roots.

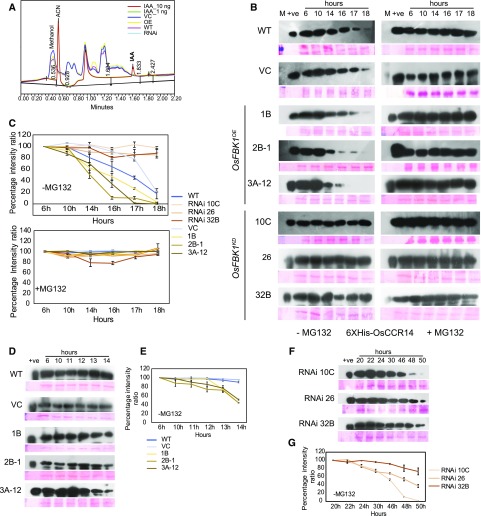

OsCCR14 Is a Substrate of the SCFOsFBK1 Complex, and Its Degradation Is Mediated by the 26S Proteasome

The expression of OsCCR14 was first checked in the transgenics of OsFBK1 by qPCR (Supplemental Fig. S6D), where the data obtained clearly show that there is no change in the transcript abundance of OsCCR14 in the transgenics, indicating that regulation of OsCCR14 takes place at the protein level. To establish whether OsCCR14 is a substrate of OsFBK1, its degradation in the transgenics was examined in a cell-free environment. Also, to determine whether auxin aids in this process, 5-d-old coleoptiles (leaf emergence, high OsFBK1-, OsCCR14-expressing tissue; Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S6B) were first examined for auxin content by UPLC. Figure 6A shows that measurable IAA is negligible in these tissues (this is expected as auxin levels are said to diminish after leaf emergence) and hence might not be available endogenously during the process of degradation. As evident from Figure 6B, the degradation of externally added 6XHis OsCCR14 (competitive degradation) to the total protein extracted from OsFBK1OE seedlings commenced earlier than wild type and VC, while in the OsFBK1KD extracts, degradation was not apparent during the experimental time period, implying that the turnover of OsCCR14 is mediated by OsFBK1. However, degradation was not seen in the transgenics and the wild type when MG132 was added to the reactions, further confirming that degradation of OsCCR14 is mediated by the 26S proteasome and does not require the presence of auxin. The kinetics of degradation of OsCCR14 in the OsFBK1 transgenics and controls have been graphically represented in Figure 6C, and it is evident that degradation of OsCCR14 commences earlier in the overexpression lines vis-à-vis wild type and VC for the present experimental time frame. Since it seems from Figure 6C that OsCCR14 is completely stable between 6 and 10 h and disappears quickly in the OsFBK1OE lines from 14 h, we have further investigated the degradation kinetics on an hourly basis in these lines during the 10- to 14-h time period. As is clear from Figure 6, D and E, degradation of OsCCR14 initiates from the 12 h of incubation onwards in the OsFBK1OE lines, while it remains stable in the wild-type and VC cell extracts. The faster degradation of OsCCR14 in the overexpression lines could be attributed to accumulation of higher protein levels of OsFBK1 as compared to wild type and VC (Fig. 2, B and C). However, it was also observed in Figure 2, B and C, that the OsFBK1KD line RNAi 10C retained 60% of OsFBK1 protein, much more than the other two lines. Thus, to check if there are any differences in the degradation kinetics among these three knockdown lines, the duration for the cell-free experiment was extended until 50 h. As is evident from Figure 6, F and G, the cellular extract from RNAi line 10C (due to its higher OsFBK1 content than the others) caused faster degradation of OsCCR14 as compared to those from RNAi lines 26 and 32B. Cycloheximide was omitted in the experiment as the target protein (6X His-OsCCR14) is bacterially expressed. Also, it could be concluded that while OsFBK1 expression is influenced by auxin, the function of the protein is probably not affected by auxin, as is evident from the cell-free degradation assays.

Figure 6.

Degradation of OsCCR14 is mediated by OsFBK1. A, Auxin estimation in 5-d-old coleoptiles of OsFBK1 transgenics and wild type by UPLC. Auxin standards, 1 and 10 ng. B, Cell-free degradation of 5 µg 6XHis-OsCCR14 with or without MG132 in the total plant extracts of OsFBK1 transgenics, VC, and wild-type (WT). Ponceau-stained Rubisco band has been depicted as a loading control for each blot. C, Graphical representation of the degradation kinetics of OsCCR14 in all OsFBK1 transgenics and controls in both presence and absence of MG132. Error bars denote sd. D, Cell-free degradation of OsCCR14 in wild-type, VC, and OsFBK1OE lines on an hourly basis (10–14 h) in the absence of MG132. Loading control is the Rubisco band stained by Ponceau. E, Graphical representation of the hourly degradation kinetics of OsCCR14 in OsFBK1OE cell-free extracts without MG132. Error bars represent sd. F, Extended cell-free time-kinetics degradation of OsCCR14 in OsFBK1KD lines in absence of MG132. Loading control, Rubisco. G, Percentage intensity ratio graph of OsCCR14 degradation in the RNAi lines. Error bars denote sd.

OsCCR14 Knockdown Transgenics Display Loss of Lignification in Their Anthers

Finally, as a proof of concept, RNAi rice transgenics of OsCCR14 (OsCCR14KD) were raised in PB1 variety; the expression of the gene in 14-d-old transgenics was checked by qPCR, lignin of roots of 14-d-old seedlings quantified, and the cleared anthers observed under UV. Figure 7A shows that the transgenics had a knockdown expression of OsCCR14, and the roots of the transgenics accumulated much less lignin vis-à-vis wild type (Fig. 7B). As evident from Figure 7C, secondary wall depositions were much less in the apex and base of the anthers of the OsCCR14KD lines as compared to wild type. These changes observed in lignin accumulation in both roots and anthers in OsCCR14KD transgenics correspond to the ones observed for OsFBK1OE plants, thereby providing a direct correlation between the two.

Figure 7.

Expression and lignin analyses of OsCCR14 knockdown lines. A, Real-time PCR of OsCCR14 in OsCCR14KD transgenics. Error bars denote sd. B, Estimation of lignin accumulation in roots of OsCCR14KD transgenics. Error bars denote sd. C, Wall morphology of OsCCR14KD anthers. Confocal microscopy of cleared anther apex and base of OsCCR14KD transgenics. Autofluorescence under UV. Bar = 50 µm. The U-shaped thickenings are denoted by arrows. Asterisk denotes separate locules in the same frame.

DISCUSSION

The FBP OsFBK1 Is a Component of an SCF E3 Ligase

Expression analyses showed that in the reproductive tissues, the transcript abundance of OsFBK1 is high in early panicle stages and anthers, whereas in the vegetative tissues it is the root. This was corroborated in the panicle protein extracts by western analysis using anti-OsFBK1 polyclonal antibodies. At the same time, OsFBK1 is induced by both auxin and ABA. The hormone ABA is a known stress hormone, and its levels are altered under both environmentally and developmentally induced stresses such as abiotic stress and induction of seed dormancy, etc. In recent years, the role of auxin in both abiotic and biotic stresses has also been established (Sharma et al., 2015). Since OsFBK1 is induced under stress and is also expressed during panicle development in a stage-specific manner, it could be coregulated by both developmental and environmental cues.

The rice genome contains close to a thousand FBP genes, out of which it has been postulated that only a couple hundred of them are functional (Hua and Vierstra, 2011; Hua et al., 2011). The mere presence of an F-box domain does not qualify it to be a functioning protein unless it can interact with the Skp1 component of the SCF E3 ligase to form a complex that identifies the substrate and then binds with the cullin scaffold. The positive interactions of OsFBK1 with two ubiquitously expressing Skp1 in rice, OSK1 and OSK20, proved that it has a valid F-box domain. The multiple sequence alignment of the F-box domains found in its closest orthologs in plants and animals showed that it has a high sequence similarity to the canonical F-box domain defined in humans (Schulman et al., 2000), albeit with plant-specific aa substitutions (Supplemental Fig. S1B). By adopting a modified Y2H approach, it was proved that the OsFBK1-OSK1/20 complex is capable of interacting with the rice cullin proteins (CUL1g/CUL5g) to form a putative SCFOSFBK1 E3 ligase. The interaction between CUL and RBX1, however, needs to be verified to generate the complete E3 ligase. The primary function of FBPs, i.e. substrate recognition, is facilitated by the C-terminal domains of FBPs. These domains aid in identifying target proteins after the phosphorylation of a specific sequence in the substrate, to which the FBPs and the E3 ligases bind noncovalently and enable SCF complexes and protein kinase pathways to work in tandem to control substrate abundance (Skowyra et al., 1997; Wu et al., 2003). The vast number of FBPs can be attributed to the presence of a large number of different C-terminal domains. The β-propeller-forming domains like WD40 (less common in plant FBPs than animals) and Kelch (unique to plant FBPs, only six known in humans) exhibit extensive similarities not only in their structures, but also in the types of molecular functions they perform (Hudson and Cooley, 2008). The Kelch motif was discovered in 1993 as a repeat element in the sequence of the Drosophila melanogaster Kelch ORF1 protein. This motif is ancient and has dispersed widely during evolution. Due to the low sequence identity between individual motifs, predictions given by popular sequence-scanning programs are insufficient (Xue and Cooley, 1993; Bork and Doolittle, 1994). Contrary to the predictions given by SMART and Pfam, OsFBK1 has a six-bladed Kelch β-propeller at its C-terminal end. The localization and dimerization experiments showed that while OsFBK1 as a monomer was found to be present throughout the cell, only the dimer was visible in the nucleus.

Manipulation of OsFBK1 Alters the Morphology of Rice Transgenics

The OsFBK1OE lines displayed overall stunting of the plant architecture including the roots with no loss of fertility in the transgenics. On the other hand, the OsFBK1KD lines resembled the wild-type plants in all respects except for the anthers and roots. These transgenics had profuse root growth without any differences in root length. In a separate experiment carried out in our lab using contrasting rice cultivars, the expression of OsFBK1 was found to be higher under drought stress in the susceptible cultivar (Borah et al., 2017). The cultivar also has a shallow root system comparable to the OsFBK1OE lines. Since auxin also plays a role in abiotic stresses, the morphology of the roots of the transgenics could be thus explained based on stress perception possibly mediated by auxin. Although the OsFBK1OE lines had smaller sized organs, the anthers of these lines did not show any apparent size reduction; all falling under the range of 2.25 to 2.5 mm of normal mature anther length. One the other hand, OsFBK1KD line anthers displayed slight increase in their length (>2.5 mm). This experimental evidence suggests the developmental stages where OsFBK1 might function optimally and corroborate the microarray expression data based on which gene was selected for functional analysis. As auxin is known to play a role in the maintenance of root proliferation (Alarcón et al., 2012), the functions of OsFBK1 could be mediated by this hormone. Although OsFBK1 is a single-copy gene, it shares closest protein sequence homology (>50%) to OsFBK5/OsEP3. The gene ERECT PANICLE (EP3) has been reported to play a role in regulating stomatal guard cell development (Yu et al., 2015) and is responsive to cytokinin. Even the previous article that first reported the cloning of this gene had commented on the mutation in the gene that causes an increase in small vascular bundle number and in the thickness of parenchyma in the peduncle, resulting in the eponymous phenotype of erect panicle (Piao et al., 2009). In Arabidopsis, the ortholog identified as Hawaiian Skirt (González-Carranza et al., 2007) plays a role in maintaining the abscission layer in the sepals and petals, the absence of which causes these organs to fuse with the silique. Hawaiian Skirt shares ∼54% identity with OsFBK1, and it is apparent from these studies, including the present one, the functions of these orthologous genes are different from each other.

Regulation of Secondary Thickening in Anthers and Roots by OsCCR14 Turnover

FBPs are known to have dedicated as well as multiple substrates. At the same time, a single substrate might be targeted by more than one FBP (Skowyra et al., 1997; Orlicky et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2003). One of the direct methods of identifying putative partners is by Y2H screening of cDNA libraries. Since it is prudent to use tissues where the expression of the bait gene is highest, it might not always hold true as the site of action of the protein might be different from its site of production. In case of OsFBK1, based on the similarities in the profiles obtained by both qPCR and western analysis, the anther tissues were selected (Fig. 1, B–D). A few putative substrates were identified in the library screening, of which CCR14 was of greater interest keeping in view the phenotype of the rice transgenics developed with altered expression of OsFBK1. Along with dirigent, other proteins were also identified that could play a role in cell wall formation (Supplemental Table S2), indicating strongly that OsFBK1 might play a definitive role in regulation of cell wall components by modulating the protein levels of multiple substrates. The BiFC fluorescence observed in the nucleus indicates that both CCR and dirigent proteins are degraded by the 26S proteasome machinery present in the nucleus. This is not surprising, as many cytosolic proteins and enzymes in animal systems are known to be degraded by the 26S proteasome machinery of the nucleus as protein quality control, where >80% of proteasomes are accounted for in the nucleus at homeostasis in the entire cell cycle (Prasad et al., 2010). However, the biological significance of such a nucleus-specific interaction and degradation remains to be unraveled and is beyond the scope of this study.

The complex aromatic polymer, lignin, deposited in the secondary cell wall of all vascular plants has been touted as a multifaceted component. Apart from development of large amount of biomass and providing physical strength to plants, lignin is known to have profound roles in biotic and abiotic stress tolerance (Wang et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2012). Lignin is synthesized by the polymerization of hydroxycinnamyl alcohols or monolignols (Raes et al., 2003; Weng and Chapple, 2010). CCR and CAD enzymes catalyze the final conversion of hydroxycinnamoyl CoA esters to monolignols, resulting in the formation of H, G, and S lignin by radical coupling (Weng and Chapple, 2010). Recent studies have linked MYB proteins to regulatory roles inducing lignification and affecting other components required for this process (Tamagnone et al., 1998; Patzlaff et al., 2003). The development of lignified secondary walls in anther endothecial cells is the first committing step toward dehiscence. The timing of endothecium lignification greatly contributes to regularizing the timing of anther dehiscence and the role of auxin in negatively regulating this process in Arabidopsis has been reported (Cecchetti et al., 2013). At the meiotic and premeiotic stages, there is an increase in IAA concentration leading to a peak and finally declining when endothecium thickening commences resulting in the formation of a bilocular anther. Premature endothecium lignification results in precocious anther dehiscence while its absence causes sterility due to indehiscence. The IRX family of genes is known to be associated with secondary thickening and xylem tracheary element development including loss of dehiscence (Turner and Somerville, 1997; Mitsuda et al., 2005). The IRX4 gene encodes for a CCR designated as ATCCR1 in Arabidopsis. In an earlier study (Kawasaki et al., 2006), several CCR genes in rice have been identified by sequence-scanning algorithm searches. In our study, we found that a couple of them were redundant and OsCCR14 was the closest homolog to ATCCR1, along with OsCCR18. Since ATCCR1 is found to play a significant role in lignification (Patten et al., 2005; Ruel et al., 2009), it could be assumed that OsCCR14 and OsCCR18 also play important roles in the lignification process, especially in the anthers. Thus, it was imperative to observe the lignification status of OsFBK1 transgenics where the anthers displayed differences in their dimensions. The cleared anthers viewed under UV in a confocal microscope showed the differences in the dispersal of the U-shaped wall thickenings in the endothecium of the transgenics and wild type. The reduction in the amount of these thickenings in OsFBK1OE and the aberrant appearances of the ridged anther cuticle revealed the probable function of OsFBK1 in regulating the production of lignin in the anthers. This could be by the possible turnover of OsCCR14 presumably via the ubiquitin-26S proteasome pathway to maintain a steady-state level of the protein in the anthers.

Similarly, roots also accumulate lignin as they develop to cope with various environmental challenges, including abiotic stresses. Auxin causes root inhibition and triggers secondary wall development as a defense response. The role of auxin in mediating the function of OsFBK1 was tested by root inhibition assay and, as evident from the results, auxin might be directly involved in the transcription of OsFBK1 for facilitating its protein’s involvement in OsCCR14 turnover. Knockdown transgenics displayed greater root inhibition in presence of IAA than overexpression and more lignin accumulation in these tissues, substantiating further the relation between auxin and lignification. This also corroborates with our earlier published data (Borah et al., 2017) where the OsCCR14KD lines (with highest lignin accumulation) are least affected by ABA vis-à-vis wild-type and overexpression lines, thereby providing another evidence of lignin accumulation and stress alleviation. Moreover, since OsCCR14 was expressed more in the presence of auxin and in the late anther development stages and root tissues, it became clear that the combinatorial action of OsFBK1 and auxin in the regulation of OsCCR14 levels in the anthers and roots is responsible for the maintenance of the thickenings in these tissues. As expected, the endogenous auxin signaling pathway in the transgenics was unaffected, as determined by both microarray analysis and UPLC profiling of endogenous IAA concentration. Also, there were no changes in the transcript levels of OsCCR14 in the transgenics of OsFBK1, indicating that the process of regulation commences at the protein level. The faster degradation of OsCCR14 in a competitive manner in the OsFBK1OE cell-free extracts and the absence of such pattern in OsFBK1KD background as compared to wild type and VC shows that OsCCR14 is a substrate of SCFOsFBK1 and its degradation is mediated via the 26S proteasome. The absence of measurable IAA content in the cell extracts also shows that this process of turnover is unaffected by auxin (even after using different amounts of tissues up to 1g), and the differences in lignification in the roots and anthers in the OsFBK1 transgenics is due to the protein-protein interaction between OsFBK1 and OsCCR14, leading to degradation of OsCCR14. To substantiate our claims further, OsCCR14KD plants were also raised, and they too displayed lesser accumulation of lignin in roots and anthers as those observed for the OsFBK1OE lines (Fig. 7, B and C). These inverse phenotypes indicated a direct interaction between OsCCR14 and OsFBK1. However, the absence of sterility in the OsFBK1OE transgenics indicated the involvement of another CCR having a similar function as OsCCR14, and which may not be a preferred target of OsFBK1.

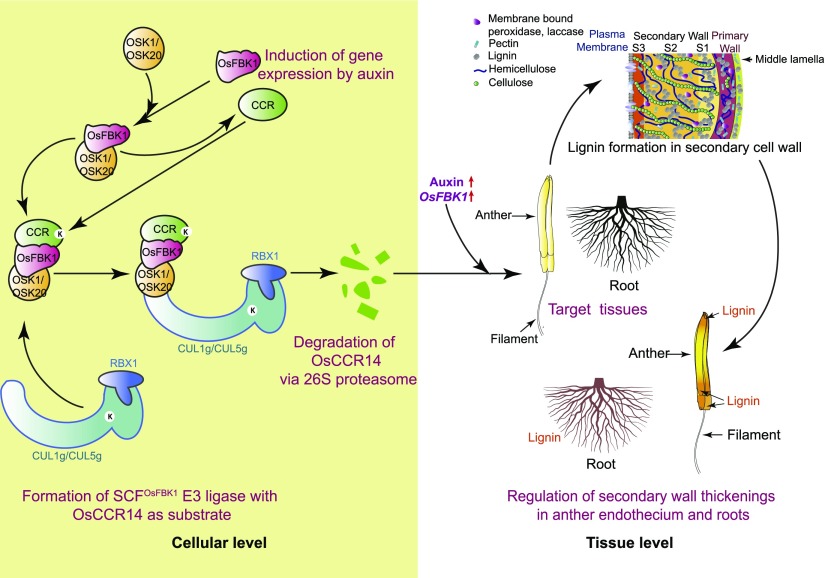

In conclusion, a model depicting the possible role of OsFBK1 in the control of anther lignification could be proposed as follows (Fig. 8): Auxin induces the expression of both OsFBK1 and OsCCR14. Upon induction, OsFBK1 interacts with the ubiquitously expressing Skp1s, OSK1/OSK20, to form the substrate adaptor complex. This complex then identifies OsCCR14 as the substrate to be ubiquitinated by the SCFOsFBK1 E3 ligase (OSK1/20-Cul1g/5g-OsFBK1). This process takes place at the cellular level and, probably, in the nucleus as shown by BiFC and cell-free studies. Turnover of OsCCR14 then takes place via the 26S proteasome. At the tissue level, this process of regulation in turn translates in the control of lignin formation in the secondary cell wall of rice anthers and root. The process of lignification in anthers is initiated by the activation of CCR by auxin and lignin deposition is concentrated in the apex and base of anthers, where optimal accumulation of lignin is important for proper anther dehiscence. Root cells also undergo secondary wall thickenings in response to stress and root growth inhibition in addition to their normal growth. By maintaining the homeostatic levels of OsCCR14, OsFBK1 thereby aids in the regulation of secondary wall thickenings in anther endothecium and roots.

Figure 8.

Model for the putative function of OsFBK1 in regulating anther and root thickenings. OsFBK1 upon being induced by auxin binds with OSK1/20, and this complex identifies OsCCR14 as a substrate. This complex then attaches with CUL1g/5g to form a SCFOsFBK1 E3 ligase that ubiquitinates OsCCR14 to be directed to the 26S proteasome for degradation probably in the nucleus. This cycle of turnover regulates the level of OsCCR14 in the cell, thereby maintaining the secondary cell wall growth of anthers and roots of the rice plant. See text for further details.

Such a regulatory process provides insights into understanding the players involved in secondary wall formation in crop plants, appreciation of the importance of the proteasome-mediated pathway in plant development, as well as having significant applications in wood-softening processes in wood and paper industries following genetic modification of commercially useful plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene Constructs and Plant Transformation

A 1,236-bp BamHI-KpnI fragment of OsFBK1 full-length cDNA KOME clone (AK121359; Rice Genome Resource Center) was cloned in the pB4NU vector for the generation of OsFBK1OE lines. For the generation of OsFBK1KD lines, a 298-bp fragment was amplified from the 3′ UTR region of the CDS of OsFBK1 with a 5′ CACC overhang using Phusion high-fidelity Taq polymerase (Finnzymes). Cloning in pENTR/D-TOPO entry vector was followed by the destination vector pANDA (Miki and Shimamoto, 2004) as per manufacturer’s instructions (pENTR Directional TOPO cloning kit, and LR clonase enzyme mix II kit; Invitrogen). A 349-bp fragment was amplified from the 3′ UTR region of OsCCR14 CDS and cloned into pANDA for the generation of RNAi transgenics. For primer sequences, refer to Supplemental Table S1.

Rice (Oryza sativa) transformation using Pusa Basmati1 indica variety was performed as per the protocol described by Mohanty et al. (1999).

Morphometric Analysis

For the measurement of anthers, predehiscent anthers of wild type and transgenics were harvested and observed under a stereo microscope (Leica S8APO). The measurements of at least 20 anthers of each construct were done using ImageJ software (https://imagej.net/). Root morphology was observed in 7-d-old seedlings and 45-d-old plants of wild type and transgenics and photographed using Nikon D80 camera.

qPCR Analysis

Total RNA isolation from different tissues of rice and after stress assays was carried out by using TRIzol reagent as per manufacturer’s instructions and as described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (1987). For the stress assays, the 7-d-old O. sativa subsp. indica var IR64 seedlings were subjected to the hormone concentrations as described by Jain et al. (2006). qPCR analysis was performed using gene-specific primers as described earlier (Jain et al., 2006). The primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Each sample with two biological replicates and three technical replicates were used for real-time PCR analysis in the LightCycler 480II Real Time system (Roche) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Particle Bombardment

The BiFC Gateway vectors, pSITE-3CA-EYFPC1 and pSITE-3CA-EYFPN1, were used for cloning OsFBK1 while pSITE-3CA-EYFPC1 was used for the cloning of OsCCR14, Dirigent, OsFBK5, and EF-Tu CDS (without stop codon) via the Gateway technology as described earlier. For localization, OsFBK1 was cloned in the pCAMBIA1302 vector (BglII/SpeI); OsCCR14, EF-Tu, OSK1, and OSK20 were cloned in pSITE-3CA destination vector. Particle bombardment for BiFC and intercellular localization in onion epidermal peel cells was carried out using Biolistic PDS-1000/He particle delivery system (Bio-Rad) according to the protocol (Lee et al., 2008) using the following parameters: 27 mm Hg vacuum, 1100 psi He pressure, target distance of 9 cm. The plates were incubated in dark for 16 h at 28°C. The onion peels were observed for GFP and YFP expression under a confocal microscope (Leica TCS, SP5). BiFC analysis was carried out twice for each combination. Negative controls for BiFC were used as per recommendations by Kudla and Bock (2016).

Protein Induction, Western Blotting, and Coimmunoprecipitation

The total protein from each panicle stage (P1–P6) was extracted using protein extraction buffer (200 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 400 mm Suc, 10 mm Na2EDTA, 14 mm β-ME, 10 mm protease inhibitor cocktail, 50 µm MG132, 0.05% v/v Tween 20, and 5% v/v glycerol). The tissue was homogenized in a prechilled mortar-pestle using liquid nitrogen, and the powder was transferred into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes (MCTs), dissolved in 0.75 volumes of extraction buffer, mixed vigorously, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 20 min at 4oC. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh MCT, quantified by Bradford assay (Bradford, 1976), and stored at −80oC for further use. For detection of OsFBK1 in the panicle stages, 10 µg total protein extract was used for western analysis with polyclonal rabbit anti-OsFBK1 antibodies and detected by chemiluminescence. For identifying the protein levels of OsFBK1 in the transgenics, 50 µg of total plant protein extract was used for western analysis, polyclonal rabbit anti-OsFBK1 antibodies were used at a 1° dilution of 1: 10,000 + 1% w/v bovine serum albumin. Secondary antibody detection was carried out using 1: 10,000 anti-rabbit antibody dilution + 1% w/v bovine serum albumin.

For coimmunoprecipitation experiments, OsFBK1 was cloned in pQE30 (Qiagen; BamHI/HindIII) for the generation of His-tagged protein, pGEX-4T-1 (GE; BamHI/EcoRI) for GST tag. OsCCR14 and Dirigent were cloned in pET28a (Novagen; both EcoRI/XhoI; see Supplemental Table S1 for primer sequences). Transformation was done in BL21-(DE3)-RIL and M15 (for pQE30) bacterial strains. In all the co-IPs, unpurified GST-OsFBK1 was used as the prey while the other unpurified 6XHis-tagged protein samples were used as bait. Crude GST extract was used as a control. Ni-NTA slurry was first washed with water and equilibrated in equilibration buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 10 mm Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, 50 µm MG132 and, 20 mm imidazole). The bait sample (70 µg) was then added to 500 µL slurry in an MCT in duplicates and allowed to be adsorbed for 2 h, 4oC, slow rotation. The samples were pelleted at 500g, 1 min, 4oC and supernatant discarded. The slurry with the adsorbed protein was washed with 5 mL of washing buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 10 mm protease inhibitor cocktail, 50 µm MG132, and 50 mm imidazole), then 70 µg of the prey proteins (GST-OsFBK1 and GST) were added and incubated for 16 to 20 h at 4oC under slow rotation. The effluent was collected, and the samples washed with 5 to 10 mL of equilibration buffer. The samples were rinsed with 5 to 10 mL of buffer A (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 10 mm protease inhibitor cocktail, 50 µm MG132, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.5% v/v Tween 20), resuspended in the remaining buffer, and divided into aliquots that were parallelly processed by western blotting using anti-His (catalog no. H1029-5ML; Sigma-Aldrich) and anti-GST (catalog no. G7781-2ML; Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies. Co-IP was carried out at least twice. Prestained markers used for all co-IP blots was Puregene NEX-GEN-PinkADD prestained protein ladder (catalog no. PG500-0500PI; Genetix Asia). Silver staining of the parallel processed gels were carried out as per manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen).

Y2H Analysis

The prey proteins (OsCCR13, Dirigent, and OSK1/20) were cloned in pGADT7 (Clontech Laboratories), while OsFBK1 was cloned in the pGBKT7 (Clontech Laboratories) bait vector. These were cotransformed in Y2H Gold yeast strain (Clontech Laboratories) and selected on SD/-Leu-Trp plates. The ΔKelch OsFBK1 construct (290–338 amino acids of OsFBK1 deleted) was generated by cloning a 1,107-bp amplicon in pGBKT7 (EcoRI/HindIII, HindII/SalI). For the modified three-way Y2H analysis, CUL1g/5g was cloned in MCS I of the pBRIDGE vector (Clontech Laboratories) while OSK1/20 was inserted in MCS II of the same. Y2H Gold competent cells were cotransformed with prey and bait constructs and plated on SD/-Leu-Met-Trp medium. Drop assay was done using 10-µL droplets of serially diluted cultures (10−1, 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4) on selection media (SD/-His-Leu-Trp for pGBKT7 and pGADT7 interactions, SD/-His-Leu-Met-Trp for pBRIDGE, and pGADT7 interactions supplemented with 3 mm 3′-AT) along with the control medium SD/-Leu-Trp or SD/-Leu-Met-Trp. The plates were incubated at 30oC till the formation of colonies.

Anther library was generated using high-quality RNA isolated from anthers of P5 (15–20 cm) and P6 (21–30 cm) stages of PB1 indica variety. Library construction in Y187 (Clontech Make Your Own “Mate and Plate” library system; Clontech Laboratories), mating with the bait (OsFBK1-pGBKT7) in Y2H Gold yeast strain, and screening was done per manufacturer’s directions. The plasmids from blue colonies were isolated as described by Ian Chin-Sang (http://post.queensu.ca/∼chinsang/lab-protocols/recovering-yeast-2-hybrid.html) and back-transformed in DH5α bacterial competent cells for sequencing.

Observation of Anther Cell Wall Thickenings

Anthers of wild type and transgenics prior to dehiscence were harvested in 70% lactic acid and incubated at 60°C for 4 d with daily changes of the solvent. Autofluorescence of the wall thickenings of the cleared anthers was then observed under UV in a confocal microscope at 60× magnification (Leica TCS, SP5). Similarly, predehiscent anthers were harvested in Trumps 4F:1G fixative, vacuum infiltrated at 4°C for half an hour, and sent for fixation and gold coating to the Advance Instrumentation Research Facility (AIRF), Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. Scanning of coated samples were carried out at 3,000× and 20,000× using Zeiss EVO40 scanning electron microscope.

Root Inhibition Assay

Nine seeds of each of wild type and transgenics were dehusked and surface sterilized with 0.1% v/v HgCl2 and plated on MS basal medium. The plates were kept vertically for 7 d under culture room conditions (28°C ± 1°C) for the development of roots. The 7-d-old seedlings were then transferred to MS basal medium supplemented with IAA (0.1 and 0.5 µm) and kept vertically in culture room. Root-length readings were taken on day 3 and root growth inhibition calculated. The experiment was carried out thrice.

Quantification of Lignin

Extraction and quantification of lignin from the roots of 14-d-old wild-type and transgenic seedlings was carried out thrice as per the protocols described by Brinkmann et al. (2002) and De Souza Bido et al. (2010). The calibration curve was generated by dissolving commercial lignin (0.01–1 mg) in 0.5 m NaOH (Aldrich; catalog no. 471003-100G) and measuring the A280.

Microarray Analysis

Seeds of OsFBK1OE, OsFBK1KD, VC, and wild type were surface sterilized and grown for 14 days at 28°C ± 1°C in half-strength MS basal medium. Total RNA was isolated from the roots, and 500 ng of each was used for microarray analysis as per manufacturer’s instructions (3′ IVT Affymetrix). Normalization of data and differential expression analysis at P ≤ 0.05 was done using Expression Console 1.4.1.46 (Affymetrix). Pathway analysis was carried by Plant MetGenMap software (Joung et al., 2009) (P ≤ 0.05). The GEO submission entry is GSE85827.

Auxin Estimation by UPLC

One gram each of 5-d-old coleoptiles/roots of 14-d-old seedlings of transgenics and wild type were homogenized in liquid nitrogen and extracted with methanol:isopropanol (20:80 v/v) with 1% v/v glacial acetic acid for 16 h at 4°C in dark. The crude 2 mL extracts were centrifuged, and the supernatants were completely evaporated at room temperature in vacuum, redissolved in 200 µL methanol, and filtered through a 0.22 µm PVDF filter (Millex). Six microliters of each sample was analyzed by UPLC (Waters) as described by Müller and Munné-Bosch (2011). Gradient elution was carried out in a 50 mm C18 column (Waters) using solvent A (0.05% v/v glacial acetic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile and 0.05% v/v glacial acetic acid) at a constant flow of 0.25 mL min−1 at 25°C for 3 min. IAA standards were of the range: 1–10 ng µL−1 (Indole-3-acetic acid, Merck; catalog no. 1.00353.0010).

Cell-Free Degradation

Total protein was extracted from coleoptiles of 5-d-old dark-grown seedlings of transgenics and wild type in extraction buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8, 10 mm MgCl2, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm DTT, 10 mm ATP, and 10 mm protease inhibitor cocktail). Incubation of purified 5 µg bacterially expressed 6× His-OsCCR14 protein at 30°C in 30 µg total protein/nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts, supplemented with or without 50 µm MG132 (catalog no. C2211-5MG, Sigma) was carried out for the requisite time points. Western analysis was performed using anti-His antibodies and detected by chemiluminescence. For loading control, the same blots were stained with Ponceau for the detection of the Rubisco protein band. For the nuclear extracts, Ponceau-stained histone H3 band was used as loading control. To graphically represent the degradation data, the intensities of the bands of all blots were measured in Image Studio Lite version 5.2 (https://www.licor.com/bio/products/software/image_studio_lite/). The 6-h western band for each blot was considered as the reference band, and observed intensities were normalized against it and multiplied by 100. Data generated were represented as percentage intensity ratio.

Accession Numbers

Microarray data from this article can be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus libraries under accession number GSE85827.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Ab initio modeling of OsFBK1.

Supplemental Figure S2. Localization of OsFBK1 and OSKs.

Supplemental Figure S3. Morphometric analysis of OsFBK1 transgenics.

Supplemental Figure S4. Protein sequence and model of ΔKelch.

Supplemental Figure S5. Silver-stained gels of the co-IPs.

Supplemental Figure S6. Phylogenetic and expression analyses of OsCCR14.

Supplemental Figure S7. Localization of OsCCR14 and EF-Tu in onion peel cells.

Supplemental Figure S8. Confocal microscopy of cleared anther apices and bases of OsFBK1 transgenics.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Table S2. Putative partners of OsFBK1 identified from anther library.

Supplemental Table S3. List of OsCCR genes.

Supplemental Data S1. Microarray analysis of roots of OsFBK1 transgenics compared to wild-type and VC plants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shane W. Rydquist for valuable help in conduct of a few experiments. P.B. thanks Sasanka Raj Deka for valuable input in conducting the statistical analyses. We acknowledge the technical support by Charu and Dr. Sangeeta of the Central Instrumentation Facility of the University of Delhi South Campus. We also thank Dr. A.K. Singh (IARI, New Delhi) for providing seeds of Pusa Basmati1. We thank the Department of Science and Technology, the University Grants Commission, and the University of Delhi for infrastructural/financial support. P.B. thanks the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi, for the award of a Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (BT/PR12394/AGIII/103/891/2014), and the ICAR-National Agriculture Innovation Project (NAIP/Comp-4/C4/C-30033/2008-09).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Alarcón MV, Lloret PG, Iglesias DJ, Talón M, Salguero J (2012) Comparison of growth responses to auxin 1-naphthaleneacetic acid and the ethylene precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxilic acid in maize seedling root. Acta Biol Cracov Ser Bot 54: 16–23 [Google Scholar]

- Ariizumi T, Lawrence PK, Steber CM (2011) The role of two f-box proteins, SLEEPY1 and SNEEZY, in Arabidopsis gibberellin signaling. Plant Physiol 155: 765–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah P, Sharma E, Kaur A, Chandel G, Mohapatra T, Kapoor S, Khurana JP (2017) Analysis of drought-responsive signalling network in two contrasting rice cultivars using transcriptome-based approach. Sci Rep 7: 42131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork P, Doolittle RF (1994) Drosophila kelch motif is derived from a common enzyme fold. J Mol Biol 236: 1277–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann K, Blaschke L, Polle A (2002) Comparison of different methods for lignin determination as a basis for calibration of near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy and implications of lignoproteins. J Chem Ecol 28: 2483–2501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti V, Altamura MM, Brunetti P, Petrocelli V, Falasca G, Ljung K, Costantino P, Cardarelli M (2013) Auxin controls Arabidopsis anther dehiscence by regulating endothecium lignification and jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Plant J 74: 411–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti V, Altamura MM, Falasca G, Costantino P, Cardarelli M (2008) Auxin regulates Arabidopsis anther dehiscence, pollen maturation, and filament elongation. Plant Cell 20: 1760–1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N (1987) Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 162: 156–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davin LB, Lewis NG (2000) Dirigent proteins and dirigent sites explain the mystery of specificity of radical precursor coupling in lignan and lignin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 123: 453–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davin LB, Lewis NG (2005) Lignin primary structures and dirigent sites. Curr Opin Biotechnol 16: 407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J, Sozen E, Vizir I, Van Waeyenberge S, Wilson Z, Mulligan B (1999) Characterization and genetic mapping of a mutation (ms35) which prevents anther dehiscence in Arabidopsis thaliana by affecting secondary wall thickening in the endothecium. New Phytol 144: 213–222 [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Bido G, Ferrarese M, Marchiosi R, Ferrarese-Filho O (2010) Naringenin inhibits the growth and stimulates the lignification of soybean root. Braz Arch Biol Technol 53: 533–542 [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Horiuchi Y, Ueda Y, Mizuta Y, Kubo T, Yano K, Yamaki S, Tsuda K, Nagata T, Niihama M, et al. (2010) Rice expression atlas in reproductive development. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 2060–2081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Carranza ZH, Rompa U, Peters JL, Bhatt AM, Wagstaff C, Stead AD, Roberts JA (2007) Hawaiian skirt: an F-box gene that regulates organ fusion and growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 144: 1370–1382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmani PS, Kamiya T, Danku J, Naseer S, Geldner N, Guerinot ML, Salt DE (2013) Dirigent domain-containing protein is part of the machinery required for formation of the lignin-based Casparian strip in the root. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 14498–14503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Z, Vierstra RD (2011) The cullin-RING ubiquitin-protein ligases. Annu Rev Plant Biol 62: 299–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Z, Zou C, Shiu SH, Vierstra RD (2011) Phylogenetic comparison of F-Box (FBX) gene superfamily within the plant kingdom reveals divergent evolutionary histories indicative of genomic drift. PLoS One 6: e16219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AM, Cooley L (2008) Phylogenetic, structural and functional relationships between WD- and Kelch-repeat proteins. Subcell Biochem 48: 6–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro S, Kawai-Oda A, Ueda J, Nishida I, Okada K (2001) The DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCIENCE gene encodes a novel phospholipase A1 catalyzing the initial step of jasmonic acid biosynthesis, which synchronizes pollen maturation, anther dehiscence, and flower opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13: 2191–2209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Nijhawan A, Arora R, Agarwal P, Ray S, Sharma P, Kapoor S, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP (2007) F-box proteins in rice. Genome-wide analysis, classification, temporal and spatial gene expression during panicle and seed development, and regulation by light and abiotic stress. Plant Physiol 143: 1467–1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Nijhawan A, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP (2006) Validation of housekeeping genes as internal control for studying gene expression in rice by quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 345: 646–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Ennos AR, Turner SR (2001) Cloning and characterization of irregular xylem4 (irx4): A severely lignin-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant J 26: 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung JG, Corbett AM, Fellman SM, Tieman DM, Klee HJ, Giovannoni JJ, Fei Z (2009) Plant MetGenMAP: An integrative analysis system for plant systems biology. Plant Physiol 151: 1758–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T (2002) MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 3059–3066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Koita H, Nakatsubo T, Hasegawa K, Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Umemura K, Umezawa T, Shimamoto K (2006) Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase, a key enzyme in lignin biosynthesis, is an effector of small GTPase Rac in defense signaling in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 230–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Delaney TP (2002) Arabidopsis SON1 is an F-box protein that regulates a novel induced defense response independent of both salicylic acid and systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 14: 1469–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YY, Jung KW, Jeung JU, Shin JS (2012) A novel F-box protein represses endothecial secondary wall thickening for anther dehiscence in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Plant Physiol 169: 212–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim OK, Jung JH, Park CM (2010) An Arabidopsis F-box protein regulates tapetum degeneration and pollen maturation during anther development. Planta 232: 353–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong H, Landherr LL, Frohlich MW, Leebens-Mack J, Ma H, dePamphilis CW (2007) Patterns of gene duplication in the plant SKP1 gene family in angiosperms: evidence for multiple mechanisms of rapid gene birth. Plant J 50: 873–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudla J, Bock R (2016) Lighting the way to protein-protein interactions: Recommendations on best practices for bimolecular fluorescence complementation analyses. Plant Cell 28: 1002–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskar DD, Jourdes M, Patten AM, Helms GL, Davin LB, Lewis NG (2006) The Arabidopsis cinnamoyl CoA reductase irx4 mutant has a delayed but coherent (normal) program of lignification. Plant J 48: 674–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Fang MJ, Kuang LY, Gelvin SB (2008) Vectors for multi-color bimolecular fluorescence complementation to investigate protein-protein interactions in living plant cells. Plant Methods 4: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Li Y, Song S, Deng H, Li N, Fu X, Chen G, Yuan L (2015) An anther development F-box (ADF) protein regulated by tapetum degeneration retardation (TDR) controls rice anther development. Planta 241: 157–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B, Gao L, Zhang H, Cui J, Shen Z (2012) Aluminum-induced oxidative stress and changes in antioxidant defenses in the roots of rice varieties differing in Al tolerance. Plant Cell Rep 31: 687–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Omasa K, Horie T (1999) Mechanism of anther dehiscence in rice (Oryza sativa L). Ann Bot 84: 501–506 [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis KM, Thomas SG, Soule JD, Strader LC, Zale JM, Sun TP, Steber CM (2003) The Arabidopsis SLEEPY1 gene encodes a putative F-box subunit of an SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase. Plant Cell 15: 1120–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki D, Shimamoto K (2004) Simple RNAi vectors for stable and transient suppression of gene function in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 490–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuda N, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Ohme-Takagi M (2005) The NAC transcription factors NST1 and NST2 of Arabidopsis regulate secondary wall thickenings and are required for anther dehiscence. Plant Cell 17: 2993–3006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty A, Sharma N, Tyagi A (1999) Agrobacterium-mediated high frequency transformation of an elite indica rice variety Pusa Basmati and transmission of the transgene to R2 progeny. Plant Sci 147: 127–137 [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Munné-Bosch S (2011) Rapid and sensitive hormonal profiling of complex plant samples by liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Plant Methods 7: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlicky S, Tang X, Willems A, Tyers M, Sicheri F (2003) Structural basis for phosphodependent substrate selection and orientation by the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell 112: 243–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osato Y, Yokoyama R, Nishitani K (2006) A principal role for AtXTH18 in Arabidopsis thaliana root growth: A functional analysis using RNAi plants. J Plant Res 119: 153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overvoorde P, Fukaki H, Beeckman T (2010) Auxin control of root development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a001537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten AM, Cardenas CL, Cochrane FC, Laskar DD, Bedgar DL, Davin LB, Lewis NG (2005) Reassessment of effects on lignification and vascular development in the irx4 Arabidopsis mutant. Phytochemistry 66: 2092–2107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzlaff A, McInnis S, Courtenay A, Surman C, Newman LJ, Smith C, Bevan MW, Mansfield S, Whetten RW, Sederoff RR, et al. (2003) Characterisation of a pine MYB that regulates lignification. Plant J 36: 743–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao R, Jiang W, Ham TH, Choi MS, Qiao Y, Chu SH, Park JH, Woo MO, Jin Z, An G, et al. (2009) Map-based cloning of the ERECT PANICLE 3 gene in rice. Theor Appl Genet 119: 1497–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad R, Kawaguchi S, Ng DT (2010) A nucleus-based quality control mechanism for cytosolic proteins. Mol Biol Cell 21: 2117–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes J, Rohde A, Christensen JH, Van de Peer Y, Boerjan W (2003) Genome-wide characterization of the lignification toolbox in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 133: 1051–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan V. (1988) Anther and pollen development in rice (Oryza sativa). Am J Bot 75: 183–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel K, Berrio-Sierra J, Derikvand MM, Pollet B, Thévenin J, Lapierre C, Jouanin L, Joseleau JP (2009) Impact of CCR1 silencing on the assembly of lignified secondary walls in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 184: 99–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samach A, Klenz JE, Kohalmi SE, Risseeuw E, Haughn GW, Crosby WL (1999) The UNUSUAL FLORAL ORGANS gene of Arabidopsis thaliana is an F-box protein required for normal patterning and growth in the floral meristem. Plant J 20: 433–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]