Recovery from N deprivation follows a distinct transcriptional program in Chlamydomonas.

Abstract

Facing adverse conditions such as nitrogen (N) deprivation, microalgae enter cellular quiescence, a reversible cell cycle arrest with drastic changes in metabolism allowing cells to remain viable. Recovering from N deprivation and quiescence is an active and orderly process as we are showing here for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. We conducted comparative transcriptomics on this alga to discern processes relevant to quiescence in the context of N deprivation and recovery following refeeding. A mutant with slow recovery from N deprivation, compromised hydrolysis of triacylglycerols7 (cht7), was included to better define the regulatory processes governing the respective transitions. We identified an ordered set of biological processes with expression patterns that showed sequential reversal following N resupply and uncovered acclimation responses specific to the recovery phase. Biochemical assays and microscopy validated selected inferences made based on the transcriptional analyses. These comprise (1) the restoration of N source preference and cellular bioenergetics during the early stage of recovery; (2) flagellum-based motility in the mid to late stage of recovery; and (3) recovery phase-specific gene groups cooperating in the rapid replenishment of chloroplast proteins. In the cht7 mutant, a large number of programmed responses failed to readjust in a timely manner. Finally, evidence is provided for the involvement of the cAMP-protein kinase A pathway in gating the recovery. We conclude that the recovery from N deprivation represents not simply a reversal of processes directly following N deprivation, but a distinct cellular state.

The ability of cells to withdraw temporarily from the cell division cycle is essential for survival during adverse conditions in unicellular organisms, and for the maintenance of tissue homeostasis in multicellular organisms. This nondividing state is termed quiescence and distinguished from senescence or terminal differentiation by its reversibility (Gray et al., 2004; Valcourt et al., 2012). Signals that promote quiescence can vary across different cell types. For instance, bacteria and yeast enter the stationary phase upon carbon exhaustion or in response to the deprivation from a specific nutrient, such as nitrogen (N), sulfur, or phosphate (Thevelein et al., 2000). Quiescence also occurs in the context of development. In plant root meristems, stem cells surround a small group of organizing cells, referred to as the quiescent center (Wildwater et al., 2005). In mammals, quiescence is seldom induced by starvation; fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and stem cells typically become quiescent unless they are exposed to proliferative signaling molecules (e.g. mitogens and antigens) or situational cues (e.g. tissue wounding; Valcourt et al., 2012). Despite these differences, many quiescence responses appear to be universal, including condensed chromosomes, reduced transcription and translation, reduced synthesis of rRNA and ribosomal proteins, and high catabolism versus low anabolism (Gray et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2004; Coller et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2010; Valcourt et al., 2012; Gifford et al., 2013). A remarkable exception in microbial quiescence is the accumulation of carbon storage compounds. Examples are glycogen, trehalose, and triacylglycerol (TAG) in yeast (Lillie and Pringle, 1980; Hosaka and Yamashita, 1984), wax and polyhydroxyalkanoates in bacteria (Daniel et al., 2004; Kadouri et al., 2005; Sirakova et al., 2012), or starch and TAG in microalgae (Moellering and Benning, 2010). Notably, there is an inverse relationship between growth and the buildup of carbon stores, which has long hampered the advancement of industrial uses of microorganisms as carbon factories. It appears to result from redirection of acetyl-CoA from the tricarboxylic acid cycle to the synthesis of fatty acids (FAs), which are then stored in the form of TAGs (Baek et al., 2011). Yeast mutants unable to produce glycogen or trehalose persist with high tricarboxylic acid fluxes during stationary phase (Silljé et al., 1999). The propensity of microorganisms to channel acetyl-CoA into reduced carbon storage compounds after entering quiescence seems to be an almost universal phenomenon accompanying impaired growth.

During quiescence, a plethora of metabolic adjustments has to take place. For example, because quiescent cells do not grow they cannot dilute out reactive oxygen species (ROS) as readily as actively growing and dividing cells. These are toxic to proteins or other macromolecules that cannot be replaced by rapid resynthesis during quiescence. Therefore, quiescent cells require specialized ROS-dissipating mechanisms to maintain redox homeostasis. Autophagy under most conditions is very limited, but is drastically elevated during quiescence, allowing for degradation and recycling of cellular components (Gray et al., 2004). For photosynthetic organisms, there is an additional challenge when entering quiescence: to reduce the highly redox-susceptible photosynthetic machinery in a way that it can be restored rapidly as conditions improve. These include transcriptional modifications, such as down-regulation of photosynthetic genes, and protein degradation, for example of light-harvesting complexes, but also the degradation of photosynthetic membrane lipids and subsequent storage of acyl groups in TAG. In addition, diverting photosynthate to complex carbohydrates is believed to be a necessary adjustment to avoid harmful ROS production in microalgae (Li et al., 2012b; Juergens et al., 2016). Conversely, it is plausible to expect highly coordinated processes that safeguard the successful recovery from quiescence in photosynthetic organisms. However, our current understanding of these coordinated recovery mechanisms is lacking.

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a unicellular green alga, offers several advantages for researching life cycle transitions in photosynthetic eukaryotes. First, the two states of interest (i.e. quiescence and cell division) can be discretely defined and controlled by N availability. Second, the cell cycle arrest caused by N deprivation has all the hallmarks of quiescence, including reversibility (Bölling and Fiehn, 2005; Miller et al., 2010; Moellering and Benning, 2010; Work et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012b; Blaby et al., 2013; Schmollinger et al., 2014). Third, a mutant showing a delay in recovery from N deprivation, compromised hydrolysis of TAG7 (cht7), has been isolated (Tsai et al., 2014). CHT7 encodes a putative DNA binding protein. In the absence of CHT7, a fraction of transcriptional changes that are characteristic for N deprivation-induced quiescence spontaneously occurs under N-replete conditions, pointing toward a possible role of CHT7 in governing processes relevant during cellular quiescence or during the transition between the regular cell cycle and quiescence and its reverse.

To better understand how photosynthetic cells reinitiate growth and proliferation as they exit quiescence, we applied N deprivation and resupply to induce the entry and subsequent exit from quiescence, respectively. We undertook comparative transcriptomics of the cht7 mutant and its parental line (PL), and conducted metabolite measurements to validate some of the transcriptomics-based findings.

RESULTS

Cytological Parameters for Setting up the RNA-Seq Experiments

Previously, we conducted Illumina RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on the cht7 mutant and the respective PL grown under N-replete (midlog phase of a culture in standard Tris-acetate phosphate [TAP] medium) and N-deprived (48 h in TAP lacking N) conditions under continuous light (70–80 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1; Tsai et al., 2014). Here, we expand this study by including two additional conditions: 6 and 12 h of N resupply following 48 h of N deprivation (abbreviated throughout as NR6 and NR12, respectively; Supplemental Fig. S1). The NR6 and NR12 RNA samples were harvested, prepared, and sequenced alongside with the N-replete and N-deprived samples published previously, allowing for accurate cross comparisons. The timing of sampling during N resupply (i.e. NR6 and NR12) was based on observations of cytological changes, and typically falls into the period of key transitions during the recovery from N deprivation. It is known that mRNAs are rapidly degraded in dying cells (Thomas et al., 2015). To be certain that dying cells potentially arising during N deprivation would not confound subsequent analyses, RNA integrity was examined with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies), and every sample had a similar RNA integrity number >7.0, indicating that these RNA samples likely captured the viable cells.

During N resupply, cell number, cell size distribution, and changes in DNA ploidy were monitored using FACS to test for the uniformity of the cells in culture and particularly during recovery from N deprivation. At 48 h of N deprivation (0 h of N resupply), PL cells had a mean volume of 76.4 μm3, which increased to 106.3 μm3 after 9 h of N resupply and to a peak value of 122.1 μm3 within the first 12 h (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S2). On average, cht7 cells did not enlarge to the same extent as PL cells. Past 12 h post N resupply, PL cells began to divide as indicated by an increase in numbers and concomitant decrease in cell size; after 24 h the cell number increased by 161% for PL, but only by 25% for cht7 (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S2).

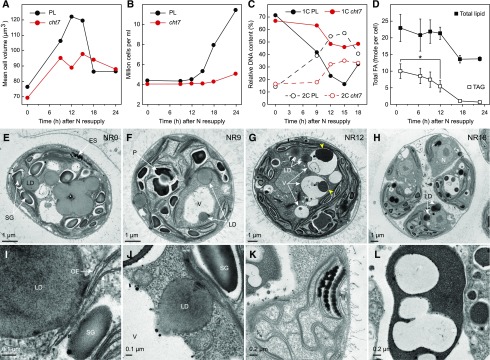

Figure 1.

Cytological parameters of N-resupplied cells. A and B, Size distribution (A) and cell count (B) of the PL and cht7 cells at different times (h) following N resupply. C, Relative DNA content of the PL and cht7 following N resupply. 1C and 2C, one copy and two copies of chromatin content. Five independent biological repeats were examined for (A–C), all showing a similar pattern with one representative result depicted. Results shown here in A and B are from the same experiment. D, Per cell FA content for total lipid and TAG following N resupply of the PL. Averages (n = 3) and sd are indicated. E to H, Transmission electron micrographs showing an overview of wild-type CC-125 cells at the indicated time points (h) during N resupply (NR). The darkly stained vacuole bodies are marked by yellow arrows. I to L, Closer details of subcellular organization of NR12 CC-125 cells. Physical contact of lipid droplets with the chloroplast outer envelope (I); small lipid droplet fused with the vacuole (J); space between thylakoid membranes (K); internal degradation of the unknown vacuole body (L). The scale bar is indicated in each panel. ES, Eyespot; LD, lipid droplet; OE, chloroplast outer envelope; P, pyranoid; SG, starch granule; V, vacuole.

Measurements of DNA content corresponded to the observation of cell growth. After 48 h of N deprivation, PL and cht7 cells had similar distributions of DNA contents (Fig. 1C; NR0). Following N resupply, the fraction of 1C (1× chromatin content) PL cells gradually decreased and the fraction of 2C (2× chromatin content) cells increased; in contrast, within the population of cht7, a greater fraction of cells remained at 1C during the observation period.

C. reinhardtii undergoes multiple rapid divisions bypassing G1 without initially releasing the progeny cells from the mother cell (Bisova et al., 2005), and hence, the DNA content in C. reinhardtii per particle (cell or mother cell) can be >2C (note that the sum of 1C and 2C relative DNA content at any given time point does not equal 100%). In the PL, TAG accumulated during N deprivation began to be degraded between 6 and 9 h after N resupply (Fig. 1D). By 12 h, about one-half of the TAG was gone; intriguingly, total FA content per cell remained unchanged. TAG reached a basal steady state in the next 6 h and the FA content stabilized afterward.

N deprivation drastically changes the ultrastructure of C. reinhardtii cells, causing vacuolization, replacement of stacked thylakoids by starch granules, and the accumulation of lipid droplets (Moellering and Benning, 2010; Yang et al., 2011; Chapman et al., 2012). Transmission electron micrographs (TEMs) were taken over a time course of N resupply to investigate ultrastructural changes occurring during exit from quiescence (Fig. 1, E–H; Supplemental Fig. S3, A–H). During the first 12 h after N resupply, lipid droplets decreased in size while the surface monolayer remained continuous with the chloroplast outer envelope membrane (Fig. 1I; Supplemental Fig. S3, I–M). This apparent membranous continuum between lipid droplet and chloroplast outer envelope membrane forms during lipid droplet formation (Wang et al., 2009), and may enable the transport of proteins and polar lipids back to the chloroplast (Tsai et al., 2015). Nine to twelve hours after N resupply smaller lipid droplets appeared to move toward the vacuole and even entered it (Fig. 1, F, G, and J; Supplemental Fig. S3, N–P). Note that at this stage, there was no longer a clear delineation between lipid droplet and vacuole as compared to the beginning of N resupply (Supplemental Fig. S3Q). This is reminiscent of lipid droplet degradation in plant seeds and in budding yeast, where lipid droplet interaction with vacuoles in a process that resembles microautophagy has been observed (Poxleitner et al., 2006; van Zutphen et al., 2014). Starch granules decreased in quantity and size (Fig. 1, F, G, and K; Supplemental Fig. S3R). Vacuoles of N-resupplied cells were smaller compared with those of N-deprived cells, which often filled the entire cytoplasm (Supplemental Fig. S3, A and B). These vacuoles typically contained darkly stained round-shaped structures (Fig. 1G, yellow arrows; Supplemental Fig. S3, C and D), which strongly resembled the protein bodies found in protein storage vacuoles (Herman and Larkins, 1999). As time proceeded, these structures appeared to break down from the inside (Fig. 1L; Supplemental Fig. S3, S and T). Finally, cells were observed to divide before fully degrading lipid droplets and starch granules as these were found in new daughter cells (Fig. 1H; Supplemental Fig. S3, G and H).

Based on the observations above, the bulk of changes in cell physiology and cell structure of the PL occurred during the first 12 h following N resupply. At NR6 changes in cell structure were clearly visible, therefore representing an early stage of N recovery. At NR12, cells were still undergoing changes, but beginning to resume cell divisions at least in the PL. We therefore chose NR6 as a representative early stage and NR 12 as a representative of a later stage during recovery from N deprivation for subsequent transcriptome analyses.

Transcriptome Dynamics across N-Replete, N-Deprived, and N-Resupplied Conditions

Using a sub-data set, we previously showed that when PL cells transitioned from N-replete to N-deprived conditions, 2,647 genes were up-regulated and 3,346 down-regulated (Tsai et al., 2014). By comparing transcripts of NR6 PL and NR12 PL with those of N-deprived PL (for the complete data set, see Supplemental Data Set S1), we found that in response to N resupply many genes reversed their expression as seen under N deprivation over time. We divided these genes into three different phases: early-, mid-, and late-reverse, respectively (Fig. 2A). Taking the 2,647 up-regulated genes during N deprivation as an example, 1.405 of these reversed at least 2-fold (log2 ≤ −1 with a P value < 0.05) at NR6. These were defined as early-reverse with 1,309 of the 1,405 genes still at least 2-fold reversed at NR12. Another 519 genes reversed only at NR12 and were defined as mid-reverse; 723 genes had not reversed by NR12 and were assumed to reverse at later times and were defined as late-reverse. Likewise, of the 3,346 genes down-regulated during N deprivation, 1,208 (1.136 were still at least 2-fold reversed at NR12), 991, and 1,147 genes were defined as early-, mid-, and late-reverse, respectively (Supplemental Data Set S2).

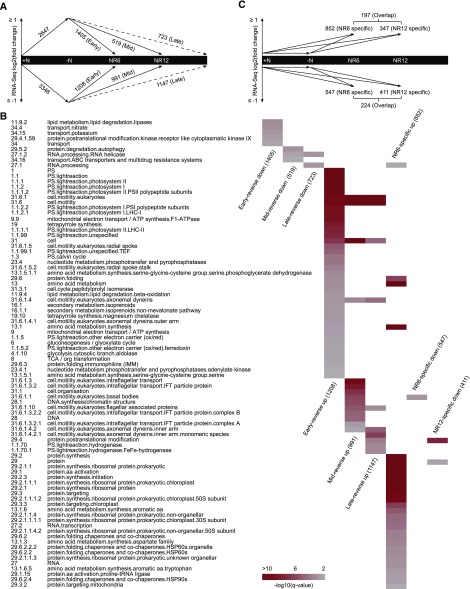

Figure 2.

Summary scheme of transcriptomic analyses across different N regimes. A, Graphic illustration of the early-, mid-, and late-reverse gene groups in the PL. Numbers represent the transcripts whose abundance changed according to the N status using a 2-fold cutoff (log2 fold change equals to 1) and a P value < 0.05. +N, N-replete; -N, N-deprived; NR6 and NR12, 6 and 12 h of N resupply, respectively. Numbers associated with the dashed line were inferred. B, Heat map of the overrepresented MapMan categories in the early-, mid-, late-reverse and NR-specific gene groups. The first column has the bin code of the categories and the second column lists the explanation of each category. The color in the heat map represents the -log10 of the q-value obtained from Fisher’s exact test ranging from 1.3 to 10 (0.05–1E-10). The number of genes in each gene group is given in parentheses near the gene group name in the x axis of the heat map. C, Graphic illustration of the NR-specific gene groups in the PL. Numbers represent the transcripts whose abundance did not vary in the –N over +N RNA-seq comparison (−1 < log2 fold change < 1), but differed over 2-fold (P value < 0.05) in both NR over +N and NR over –N comparisons.

To take a global view of the pathways most highly represented by these data sets, genes were mapped into functional categories based on the MapMan ontology (Thimm et al., 2004; May et al., 2008) and Gene Ontology (GO), and the enrichment within the up- and down-regulated groups was assessed (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Data Set S3). The prediction of gene function by MapMan is considered to be more tailored to plants than the more general GO terms (Klie and Nikoloski, 2012). Indeed, MapMan’s findings portrayed a clear succession of biological processes. Among the 75 functional categories (q value < 0.05) enriched in the early, mid-, and late-reverse gene subsets, 57 were phase-specific (appeared in only one of the subsets; Fig. 2B). Early-reverse categories are grouped as follows: (1) Lipid degradation (lipases and β-oxidation), central metabolism (gluconeogenesis/glyoxylate cycle, glycolysis, and tricarboxylic acid cycle), mitochondrial electron transport/ATP synthesis, nucleotide metabolism (pyrophosphatase and adenylate kinase), and photosynthesis are all related to the restoration of cellular bioenergetics. (2) Transport, amino acid metabolism, and tetrapyrrole synthesis (beginning from Glu), which are processes directly related to N uptake and assimilation. Nitrate transport (MapMan bin code 34.4) was over-represented among the transcripts that decreased in abundance, which seems reasonable since the N deprivation had ended, and is also consistent with the fact that ammonium assimilation–the N source used in this study–suppresses the expression of nitrate reductase genes (Fernández et al., 1989). Notably, genes involved in potassium transport (MapMan bin code 34.15) were synchronously coordinated even though potassium had never been depleted, suggesting a convergent node of nutrient sensing. The nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis (MapMan bin code 16.1.1) was found among the early-reverse up-regulated categories. One possible explanation could be to provide the prenyl moiety for chlorophyll, the primary end-product of the tetrapyrrole pathway in plants (Eisenreich et al., 2001). (3) Motility-related processes (MapMan bin code 31.6 and its subcategories). It is still unclear why transcripts associated with flagellar assembly are reduced during N deprivation, especially because this treatment also induces the formation of gametes, which are flagellated (Tsai et al., 2014). However, it has been hypothesized that the assembly proteins for a primary cilium of vertebrate cells (similar to a flagellum) can also affect cell cycle progression (Pan and Snell, 2007; Snell and Golemis, 2007). Although motility-related categories are present throughout all three phases, there is a clear delineation: genes encoding axonemal outer arm dyneins (MapMan bin code 31.6.1.4.1) and radial spoke (MapMan bin code 31.6.1.5) were restricted to early-reverse, basal bodies (MapMan bin code 31.6.1.1) and intraflagellar transport complex genes (MapMan bin code 31.6.1.3) to mid-reverse, and axonemal inner arm dynein genes (MapMan bin code 31.6.1.4.2) and flagellar associated protein genes (MapMan bin code 31.6.1.10) to mid- and late-reverse. This progression may represent the stepwise formation of a eukaryotic flagellum as was also previously observed during the diurnal cycle (Zones et al., 2015).

The fact that autophagic protein degradation (MapMan bin code 29.5.2) was mid-reverse down-regulated rather than early-reverse is counterintuitive given that protein synthesis occurs immediately after N is resupplied (Tsai et al., 2014), indicating that this process is active not only during N deprivation but also extends to at least the first 6 h following N resupply. It is possible that the autophagic machinery is needed for the degradation of lipid droplets in vacuoles as suggested above (Fig. 1J; Supplemental Fig. S3Q). DNA synthesis (MapMan bin code 28.1) found in mid-reverse up-regulated categories was consistent with the measurement of DNA content (Fig. 1B). Finally, [FeFe]-hydrogenase (MapMan bin code 1.1.70.1) was found in the only non-early-reverse subcategory of photosynthesis.

Transcriptional Changes Specific to the Recovery Phase

Next, we asked whether there were unique transcriptional changes that were only apparent during the N recovery phase, which we called NR-specific. To be counted as an NR-specific gene, its relative RNA abundance must not fluctuate when shifting from N-replete to N-deprived condition (−1 < log2 < 1), but must be either up- or down-regulated in both the NR versus N-replete and the NR versus N-deprived transcriptomes (using a 2-fold cutoff and a P value < 0.05; Fig. 2C). Note that the NR-reverse (Fig. 2A) and NR-specific genes are mutually exclusive by definition, enabling us to further dissect the nature of the transcriptomes. Under these criteria, 852 (NR6-specific) and 347 (NR12-specific) genes were up-regulated after 6 and 12 h of N resupply, respectively, among which 197 genes overlapped (Supplemental Data Set S4). As for the down-regulated genes, there were 547 (NR6-specific) and 411 (NR12-specific) with 224 overlapping. A typical example of an NR-specific gene is the one encoding betaine lipid synthase (BTA1), which synthesizes diacylglyceryl-trimethylhomo-Ser (DGTS), a major lipid component presumed to replace phosphatidylcholine in extraplastidic membranes in C. reinhardtii (Riekhof et al., 2005). Transcript levels of BTA1 remained constant when entering N deprivation, but raised approximately 4-fold after 6 h and 12 h of N resupply.

In comparison to the NR-reverse data set, the enrichment of the NR-specific gene sets was much less diverse. Altogether, 31 of the total 32 categories (30 NR6-specific and 2 NR12-specific) could be attributed to amino acid, RNA, and protein-related processes (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Data Set S5). Only two (MapMan bin code 13: amino acid metabolism and 13.1: amino acid synthesis) were redundant with the NR-reverse categories (excluding those found in the Late-reverse which were beyond the NR6 and NR12 timeline). Apparently, amino acid metabolism is affected in different aspects in the two data sets, that is the NR-reverse set covers Ser (MapMan bin code 13.1.5.1) while the NR-specific set covers more the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids (MapMan bin code 13.1.6) and Asp family amino acids (MapMan bin code 13.1.3). All the NR6-specific protein-related categories came from the up-regulated gene set (852, Fig. 2C). Particularly noteworthy are those involved in protein folding (MapMan bin code 29.6.2: chaperones and cochaperones, 29.6.2.2/4: HSP60 and HSP90-like proteins), prokaryotic ribosomal protein synthesis (e.g. MapMan bin code 29.2.1.1.1.1/2: chloroplast ribosomal 30S/50S subunits), and protein targeting (MapMan bin code 29.3.3: chloroplast targeting and 29.3.3: mitochondria targeting). On the contrary, NR12-specific protein-related categories were overrepresented in the down-regulated gene set (411, Fig. 2C). Collectively, these findings suggest a unique demand for cells to rapidly remake, restructure, and transport the proteins lost during N deprivation, especially those of the chloroplast, to complete the recovery.

Acclimation Responses That Failed to Readjust in cht7 during the Recovery Phase

CHT7 encodes a putative transcription factor and without it cultures are slow to resume growth following N or phosphate deprivation, or rapamycin addition, treatments which all induce quiescence (Tsai et al., 2014). It would be expected to see differences in transcript abundance between cells that undergo orderly progression through the recovery phase and cells that fail to do so. Therefore, to identify specific misregulation of gene expression in cht7 when PL cells would be recovering from N deprivation, we adopted an integrated pairwise comparative approach (González-Ballester et al., 2010; Castruita et al., 2011). Transcripts of the PL after 6 h and 12 h of N resupply were compared with those of the N-deprived PL (Fig. 3, A and B, blue circles); transcripts of the PL after 6 h and 12 h of N resupply were compared with those of cht7 (Fig. 3, A and B, yellow circles). It should be noted that the blue circles in Figure 3A contain all the early-reverse and NR6-specific genes mentioned above, and the blue circles in Figure 3B have all the mid-reverse and NR12-specific genes. Most transcripts responsive to N resupply in the PL were readjusted normally in cht7 (Fig. 3, A and B, blue circles outside the overlap). However, a specific subset of genes did not respond in cht7 and remained at expression levels that were similar to those of N-deprived PL cells (Fig. 3, A and B, overlaps between the blue and yellow circles; Supplemental Data Set S6). It seems possible that these genes are regulated by CHT7 and that a subset of them are specifically needed for the recovery from N deprivation, whereas the changes in expression of other genes (yellow circles outside the overlap) likely reflect secondary or compensatory effects resulting from the impaired growth of cht7. Closer examination of the overlapping gene sets provided supporting evidence. Overall, 60 MapMan categories (35 of NR6 and 25 of NR12) were significantly enriched (Fig. 3C; Supplemental Data Set S7), among which 34 have been defined as NR-reverse (e.g. MapMan bin code 1: photosynthesis and its subcategories, 19: tetrapyrrole synthesis) and 14 as NR-specific (e.g. MapMan bin code 13.1.6: aromatic amino acid, 29.2.1.1: prokaryotic ribosomal protein synthesis).

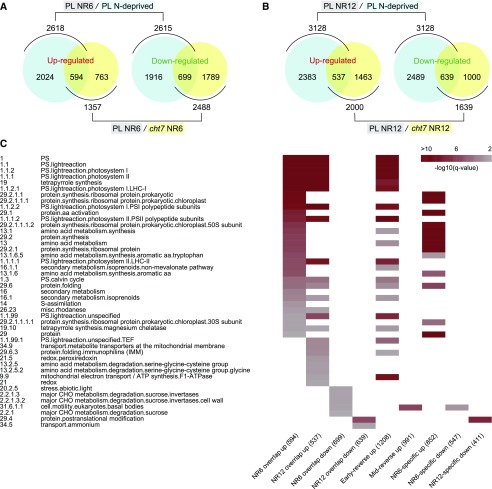

Figure 3.

Comparative transcriptomics of the PL and the cht7 mutant. A and B, Global gene expression analysis of the PL and cht7 following N resupply. Blue circles: total number of genes changed in expression in a comparison of PL after 48 h of N deprivation followed by 6 h (A) or 12 h (B) of N resupply over PL N-deprived for 48 h. Yellow circles: total number of genes changed in expression in a comparison of PL NR6 over cht7 NR6 (A) or PL NR12 over cht7 NR12 (B). NR6 and NR12, 6 and 12 h of N resupply, respectively. C, Heat map of the overrepresented MapMan categories in the overlapping gene groups as depicted in A and B. The first column has the bin code of the categories and the second column lists the explanation of each category. The color in the heat map represents the -log10 of the q-value obtained from Fishers exact test ranging from 1.3 to 10 (0.05–1E-10). The number of genes in each gene group is given in parentheses near the gene group name in the legend of the heat map.

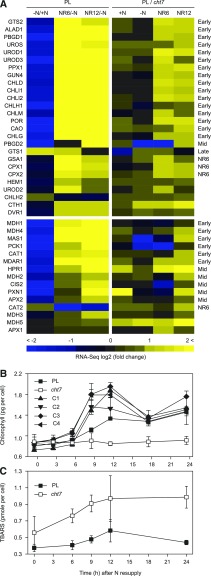

As examples, we focused on two MapMan pathways: tetrapyrrole synthesis, which was among the NR-reverse categories, but unlike photosynthesis, its transcript profile was not affected by the loss of CHT7 before the recovery phase (Tsai et al., 2014), and peroxisomal redox homeostasis (MapMan bin code 21 and 21.5), which was neither NR-reverse nor NR-specific. At 6 and 12 h following N resupply, nearly every tetrapyrrole gene showed lower transcript levels in cht7 compared with PL (Fig. 4A, top right [included here are genes that fall below the 2-fold threshold]; Supplemental Data Set S8). These genes did not greatly differ in expression between cht7 and the PL in N-replete or N-deprived conditions, but upon recovery from N deprivation. The RNA-seq data were confirmed for representative genes by quantitative PCR (qPCR) in PL and cht7 as well as cht7 complemented lines in this analysis (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Genes involved in maintaining redox homeostasis during high demand of β-oxidation were down-regulated in cht7 following N resupply (Fig. 4A, bottom right; Supplemental Fig. S4B; Supplemental Data Set S9). Catalase 1 and 2, ascorbate peroxidase 1 and 2, and monodehydroascorbate reductase are enzymes that detoxify the ROS generated as by-product of β-oxidation within the peroxisomes (Eastmond, 2007). Notably, Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genes encoding homologs of HPR1, MAS1, MDH2, MDH4, monodehydroascorbate reductase 1, and PXN1 (all misregulated in cht7 at NR12) cause mutant phenotypes when disrupted, affecting seed oil breakdown and seedling establishment (Graham, 2008; Theodoulou and Eastmond, 2012), reminiscent of the defects of cht7 in TAG turnover and regrowth. The changes in transcript abundance were corroborated at the metabolite level. Chlorophyll contents of the PL and complementation lines increased after 6 h of N resupply, and decreased after 12 h likely because of cell divisions (Figs. 1C and 4B). In contrast, the chlorophyll content of cht7 remained constant throughout the same period. TBARS, the cellular metabolites reflecting the damage caused by ROS, were accumulating in cht7 after transfer to N-replete medium (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Gene expression and metabolite level for two selected pathways. A, Overview of the expression of genes involved in the tetrapyrrole pathway (top) and in peroxisomal redox homeostasis (bottom). RNA-seq comparisons of the PL at different N status and the comparisons between PL and cht7 at each N status are shown in the heat map. +N, N-replete; -N, N-deprived; NR6 and NR12, 6 and 12 h of N resupply, respectively. For the genes whose expression pattern following N resupply has been classified, the respective categories are indicated on the right of the heat map. Early, Early-reverse; Mid, mid-reverse; Late, late-reverse; NR6, NR6-specific; NR12, NR12-specific. B, Chlorophyll content. C1-C4, 4 independent complemented lines. C, TBARS content. For all quantitative data, averages (n = 3) of biological replicates and sd are indicated.

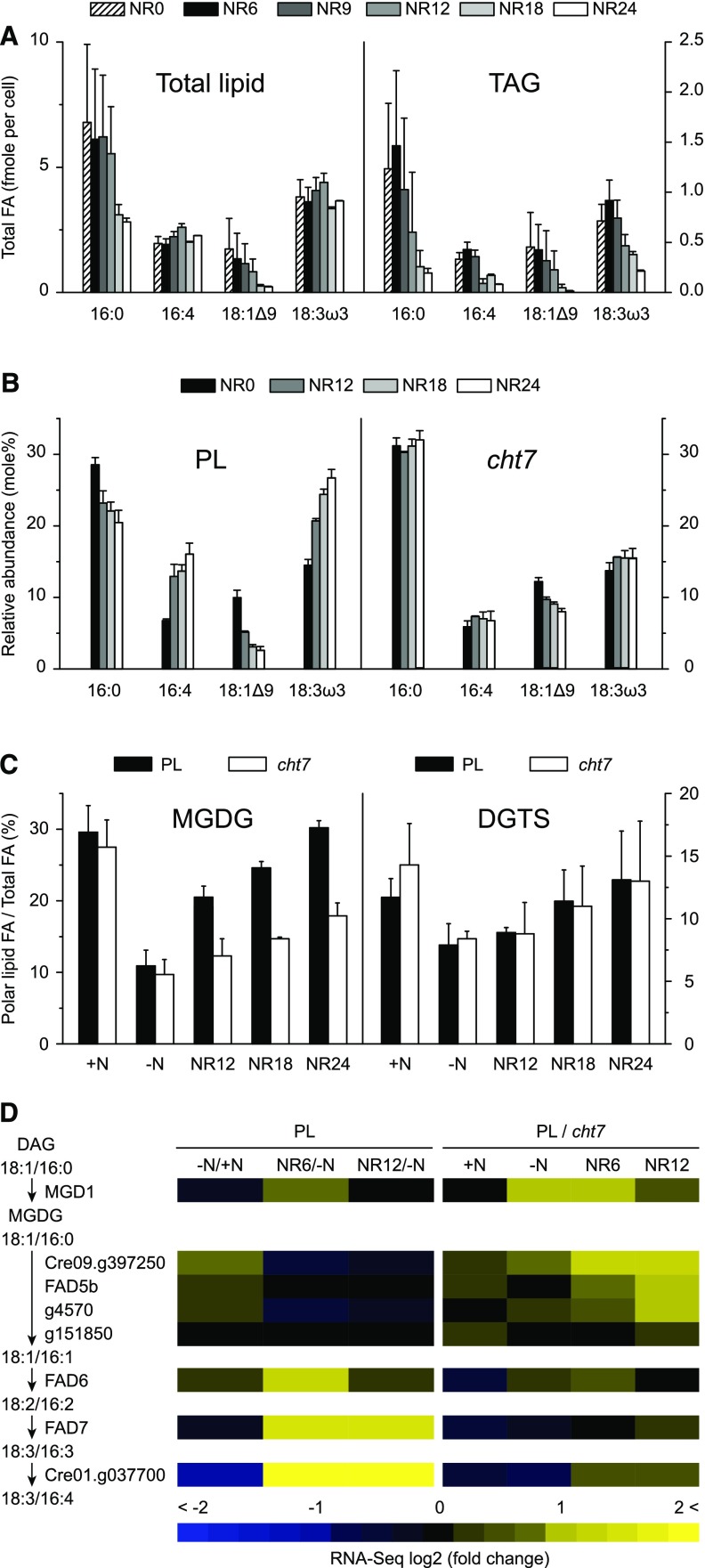

MGDG Is the Sole Polar Lipid Affected in cht7 Following N Resupply

Earlier we had shown that TAG turnover took place after 6 h of N resupply, but total FAs did not change until 12 h (Fig. 1D). A possible explanation for the discrepancy might be that between 6 and 12 h, lipolytic products from TAGs were not subjected to the β-oxidation cycle but used to reassemble membrane lipids, especially the thylakoid lipids enriched in polyunsaturated FAs. Indeed, we found that the absolute quantity of 16:4 (carbons: double bonds) and 18:3ω3 (the two major FAs of monogalactosyldiacylglycerol [MGDG]; Giroud et al., 1988) did not decrease after N resupply, but 18:1Δ9 (the signature FA of TAG; Liu et al., 2013) and other FAs did (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Fig. S5, A and B). About 25% of 16:4 and 18:3ω3 was stored in TAGs during N deprivation. While in the PL the relative abundance of 16:4 and 18:3ω3 increased gradually following N resupply, the FA profile of total lipids remained static in cht7 (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Fig. S5, C and D). Accordingly, among all the polar lipids being tested including DGTS, digalactosyldiacylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, and sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol, the cht7 mutant was unable to restore MGDG following N resupply (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Fig. S6, A–E).

Figure 5.

Lipid analysis and the expression profile of MGDG synthesis genes. A, FA content of total lipid and TAG in the PL following NR at times indicated (h). B, Relative FA compositions of PL and cht7 following N resupply. FAs are designated by the total carbon number followed by the number of double bonds. The position of specific double bonds is indicated either from the carboxyl end “Δ” or from the methyl end “ω.” C, Polar lipid contents in the presence (+N, N-replete) or absence (−N, N-deprived) of N, or following N resupply at times indicated. The y axis is depicted as the ratio of individual polar lipid FAs over total FAs. Averages (n = 4) of biological replicates and sd are indicated. D, Overview of the expression of genes responsible for MGDG synthesis. RNA-seq comparisons of PL at different N status and the comparisons between PL and cht7 at each N status are shown in the heat map. Arrows indicate the sequence of reactants. FAs at the sn-1/sn-2 position of diacylglycerol (DAG) or MGDG are shown.

Data obtained at the transcript level are insufficient to provide a cause for the MGDG phenotype. Responding to N resupply, only the genes encoding MGDG-specific desaturases (FAD6, FAD7, and the C16 Δ4-desaturase) had increased mRNA abundance, and their expression was normal in cht7 (Fig. 5D; Supplemental Data Set S10). Besides, none of the MGDG synthesis genes was a candidate for CHT7-specific regulation (found in the overlaps between the blue and yellow circles in Fig. 3, A and B). The inability of cht7 to readjust MGDG may be, at least in part, a consequence of the delay in TAG turnover, which could normally contribute precursors for chloroplast lipid assembly.

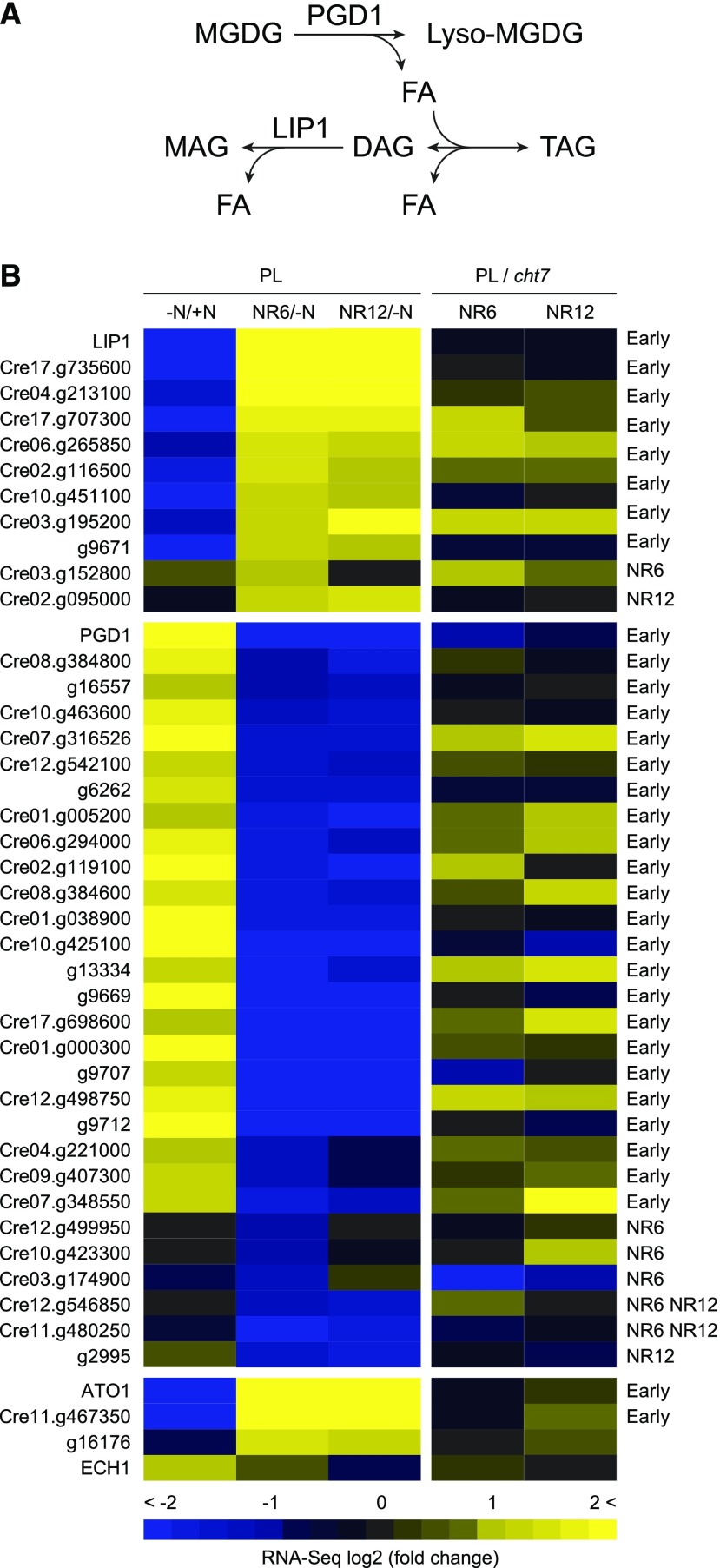

Functional Curation of Lipid Metabolism Genes Based on Expression Patterns

RNA-seq resources generated in this study allow us to filter and classify functionally ambiguous genes. Here we focus on lipid metabolism (Supplemental Data Set S10). Lipases are a subclass of acyl hydrolases that deesterify carboxylic esters, and can affect TAG metabolism both positively (e.g. PGD1; Li et al., 2012b) and negatively (e.g. LIP1; Li et al., 2012a), as illustrated in Figure 6A. Since TAGs increase during N deprivation and decrease following N resupply, we expected that genes encoding TAG-hydrolyzing lipases (e.g. LIP1) would be down-regulated during N deprivation and up-regulated after N resupply (NR-reverse) or just up-regulated after N resupply (NR-specific; Fig. 6B, top left). On the contrary, genes encoding TAG-producing lipases (e.g. PGD1) would respond in an opposite direction (Fig. 6B, middle left). Following this principle, we sorted through 131 genes predicted to encode a lipase, phospholipase, or patatin based on the GXSXG motif common to hydrolases, and assigned 9 TAG-hydrolyzing lipases and 23 TAG-producing lipases with LIP1 and PGD1 defining their respective class. Candidate genes encoding β-oxidation enzymes such as ATO1 and acyl-CoA oxidases were coordinated with those encoding TAG-hydrolyzing lipases (Fig. 6B, bottom left), with the exception of the gene for ECH1, a specialized enoyl-CoA oxidase/isomerase needed for unsaturated FAs (Goepfert et al., 2008). Notably, Cre17.g707300, Cre06.g265850, Cre03.g195200, and Cre03.g152800 (TAG-hydrolyzing) and PGD1, Cre10.g425100, g9707, and Cre03.g174900 (TAG-producing) were misregulated in cht7 in either or both NR6 and NR12 conditions in a way that would cause TAGs to be retained in the cells, making these promising candidates for reverse genetic studies (Fig. 6B, top and middle right).

Figure 6.

Gene expression of putative lipase and β-oxidation genes. A, An example depicting how lipases might positively or negatively influence TAG content. MAG, monoacylglycerol; PGD1 and LIP1, lipases. B, Transcript profiles of genes encoding lipases possibly involved in the degradation of TAG (top), in the production of TAG (middle), or in β-oxidation (bottom). RNA-seq comparisons of the PL at different N status and the comparisons between PL and cht7 at each N status are shown in the heat map. +N, N-replete; −N, N-deprived; NR6 and NR12, 6 and 12 h of N resupply. For the genes whose expression pattern following N resupply has been classified, the respective categories are indicated on the right of the heat map. Early, Early-reverse; Mid, mid-reverse; Late, late-reverse; NR6, NR6-specific; NR12, NR12-specific.

For newly synthesized FAs in the form of acyl-ACP (acyl carrier protein) to be exported out of plant chloroplasts, the ACP moiety must be removed by the activity of acyl-ACP thioesterase, and almost instantly long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase activates the resulting free FAs to acyl-CoA so they can be incorporated into glycolipids such as TAG (Li-Beisson et al., 2013). Likewise, FAs hydrolyzed from TAGs also need to be converted to acyl-CoA prior to β-oxidation. Two isoforms of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase exist in the C. reinhardtii genome, LACS1, and LACS2. Transcripts of LACS1 increased in abundance when shifting to N-deprived medium and recovered when the condition was reversed; those of LACS2 reacted just the opposite (Supplemental Data Set S10). It is thus likely that LACS1 works in tandem with acyl-ACP thioesterase, and LACS2 channels precursors into β-oxidation. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase (type 2, DGTT) is a key enzyme for TAG biosynthesis. Of the five putative candidates, only the expression of genes encoding DGTT1 and DGTT5 paralleled the accumulation of TAG. Expression of the gene for DGTT4 was NR-specific with a near 4-fold mRNA increase at 6 and 12 h of N resupply, the time that TAGs were being degraded. The seemingly conflicting finding may be reconciled by hypothesizing that during recovery from N deprivation there is a need to fine-tune FA production and sequestration into TAG to avoid the toxicity of free FAs or that nontranscriptional regulation comes into play, which is not considered here.

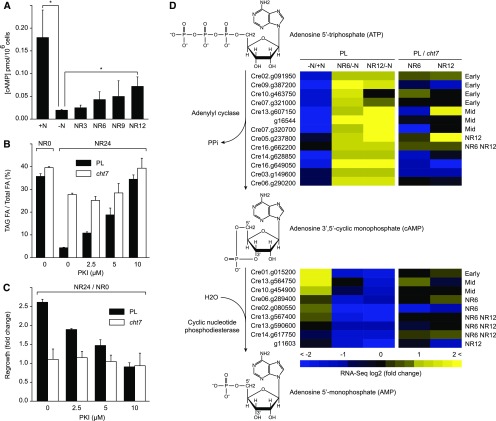

A cAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Pathway Is Required for Quiescence Exit

Adenylyl cyclase converts ATP to cAMP, and binding of cAMP to the regulatory domains of protein kinase A (PKA) facilitates the phosphorylation of diverse enzyme targets. In yeast, the PKA signaling cascade negatively affects quiescence (Gray et al., 2004). Therefore, we asked whether PKA could have an impact on quiescence in C. reinhardtii. Competitive ELISA showed that concentrations of cAMP responded to the presence and absence of N (Fig. 7A), a prerequisite for a possible role of PKA activity during recovery from N deprivation. To verify this hypothesis, we took a pharmacological approach. A 20-amino acid fragment of a naturally occurring PKA inhibitor (PKI) is known to bind and inhibit the catalytic domain of PKA (Knighton et al., 1991). Derivatives of this fragment have been used to study flagellar assembly in C. reinhardtii (Howard et al., 1994). When applied simultaneously with N refeeding, PKI interfered with TAG turnover in the PL in a dosage-dependent manner (Fig. 7B). FA profiles of PL cells treated with PKI resembled those of nontreated cht7 (Supplemental Fig. S7). Addition of 10 μm of PKI caused severe chlorosis indicative of cell death, and no degradation of TAG was observed in the PL or cht7. Importantly, within the nontoxic range (0 to 5 μm), PKI did not exacerbate the lipolytic defect in cht7. PKI treatment also mimicked the slow regrowth of cht7 in the PL (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

The effect of the cAMP-PKA pathway on the recovery from N deprivation. A, ELISA assay to quantify the cellular content of cAMP in the PL. +N, N-replete; −N, N-deprived; NR, N resupply at times indicated (h). Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (unpaired t test, P < 0.05). B, TAG degradation of PL and cht7 in the presence of PKI. The TAG content (depicted as the ratio of TAG FA over total FA) of cells just before N resupply (designated here as NR0) is shown on the far left. TAG contents of cells treated with different concentrations of PKI (as indicated in the x axis) were quantified at 24 h of N resupply (NR24). C, The regrowth of PL and cht7 in the presence of PKI. The fold change of regrowth is calculated by dividing the cell count measured at 24 h of N resupply by that at 0 h of N resupply (NR24/NR0). PKI treatments in B and C were done simultaneously with N resupply. D, Transcript profiles of genes encoding putative adenylyl cyclase and phosphodiesterase. RNA-seq comparisons of PL at different N status and the comparisons between PL and cht7 at each N status are shown in the heat map. For the genes whose expression pattern following N resupply has been classified, the respective categories are indicated on the right of the heat map. Early, Early-reverse; Mid, mid-reverse; Late, late-reverse; NR6, NR6-specific; NR12, NR12-specific. For all quantitative data, averages (n = 3) and sd are indicated.

Adenylyl (and guanylyl) cyclases form one of the largest families in the genome of C. reinhardtii (Merchant et al., 2007), and their activities are counteracted by cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases that turn cAMP into AMP. Stimulating the activity of phosphodiesterase attenuates cAMP-mediated lipolysis (Botion and Green, 1999). At a glance, many of the candidate genes were differentially regulated by N availability and by the loss of CHT7 (Supplemental Data Set S11). Here we assigned potential adenylyl cyclases and phosphodiesterases whose expression profile matched the observed fluctuation of cAMP (Fig. 7D).

DISCUSSION

To grow or not is a fundamental decision that every cell has to make in response to developmental, metabolic, or environmental stimuli. Based on this decision, cells either progress through the cell division cycle or enter into quiescence. While yeast offers a well-studied model of quiescence, fairly little is known in eukaryota outside of fungi and certain mammalian cell lines, photosynthetic eukaryotes in particular. From a biological standpoint, the reversible cessation of growth depending on nutrient availability provides a facile experimental system to study quiescence. N deprivation is thus far the most effective way to induce the accumulation of neutral lipids in microalgae, for experimental purposes to study quiescence-related phenomena or for practical reasons in developing algae as a renewable energy source (Hu et al., 2008). Cellular responses to N deprivation have been studied on multiple -omic levels, drawing an integrated picture of N economy (Miller et al., 2010; Blaby et al., 2013; Schmollinger et al., 2014; Wase et al., 2014). In contrast, research on the recovery from N deprivation has lagged behind. Here, we used a systems biology approach to address the question of how photosynthetic cells recover from N deprivation to begin to understand mechanism involved in quiescence exit, using C. reinhardtii as a reference model. The use of the cht7 mutant in comparative transcriptomics helped to reduce noise and unravel the transcriptional patterns potentially relevant to the resumption of growth and proliferation. While our understanding of how CHT7 affects cell viability and proliferation in response to different N regimes is only in its infancy, these data provide additional insights into the function of this potential regulator of quiescence-relevant transcriptional programs.

Quiescence Exit Is Not Simply the Reverse of Quiescence Entry

Ultimately, cells recovering from N deprivation-induced quiescence return to the G1 phase of the cell cycle. However, recovery from N deprivation is hardly the exact reversal of the processes encountered while cells become N deprived. We categorized genes that reversed their expression in response to N resupply into early-, mid-, and late-reverse groups, implicating priorities of transcriptional reprogramming. Early- and mid-reverse groups are more likely to be responsible for restarting the cell cycle, as they coincided with the time that cells began to proliferate. These unique temporal patterns of expression suggest that the recovery from N deprivation including the transition to the resumption of the cell cycle is subject to an ordered set of sequential events. In an emerging model of microbial quiescence, growth-limiting conditions appear to trigger a common pathway that reduces growth by redirecting the carbon fluxes away from the central metabolic pathways and toward storage depots (Rittershaus et al., 2013). This is especially the case for microalgae. Nutrient starvation (e.g. N, phosphate, sulfur, zinc, and iron), high salt, heat shock, and oxidative stress are all able to cause TAG accumulation (Hu et al., 2008; Matthew et al., 2009; Kropat et al., 2011; Siaut et al., 2011; Hemme et al., 2014), and TAG utilization is required for regrowth (Tsai et al., 2014). We curated every putative lipase, and of course, uncovered many that had reversed expression patterns (Fig. 6). Importantly, we also identified genes whose transcript abundance only fluctuated during the time of N recovery, termed NR6- and NR12-specific groups. This discovery provides direct evidence that the expression profile of N-resupplied cells exiting quiescence, is distinct from that of N-deprived quiescent cells or N-replete cells, which are mostly in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. TEM also captured key morphological distinctions between newly dividing N-resupplied and N-replete cells, showing that growing cells after N resupply retained small lipid droplets and starch granules, and their thylakoids were not fully stacked (Fig. 1H; Supplemental Fig. S3). However, what happens in cells during recovery from N deprivation that causes a delay before they can undergo genome replication and mitosis compared with the cells that actively traverse the cell division cycle? A 6- to 8-h doubling time for regular cycling cells was lengthened to 12 to 15 h counting from the moment that N was refed (Fig. 1B), or even longer if cells were N-deprived for long periods (Tsai et al., 2015). Aside from a reduction in viability during prolonged N deprivation, it seems likely based on the current data that this delay relates to the reorganization of metabolism. Indeed, much of the provided ontology analysis detected metabolic processes related to the synthesis of macromolecules (nucleotides, amino acids, and proteins), cellular bioenergetics (central metabolism, photosynthesis, mitochondrial electron transport, and ATP synthesis), cellular components (lipids and chlorophylls), nutrient assimilation (nitrogen and phosphate), and redox homeostasis. Perhaps the most intriguing finding was that the MapMan categories enriched in NR-specific genes appeared to center on the replenishment of chloroplast proteins. This finding fits nicely with reports that chloroplast ribosomes, specific photosynthetic electron transfer complexes, plastid ATPase, and Calvin-Benson cycle enzymes especially Rubisco, are more actively targeted by N-sparing mechanism during N deprivation in C. reinhardtii (Gray et al., 2004; Schmollinger et al., 2014). Note that elevated protein abundance of mitochondrial ATP synthase and the mitochondrial bc1 complex was apparent. Measurements of MGDG and chlorophylls, both confined to the chloroplast, also reflected a scenario of rebuilding the chloroplast (Figs. 4C and 5C). Thus, the time delay required by recovering cells might be to restore chloroplast integrity, which represents an important distinction between photosynthetic eukaryotes on one hand and yeast and mammalian cells on the other.

How Does CHT7 Facilitate the Recovery from N Deprivation?

On one hand, 34 NR-reverse categories (MapMan) failed to revert back to the state prior to N deprivation in N-resupplied cht7. This seems to support the notion that CHT7 contributes to the reversal of the quiescent state by acting as its suppressor. On the other hand, the finding of 14 NR-specific gene expression categories that appeared in N-resupplied cht7 as if cells were still under N deprivation suggests that CHT7 has additional, specific functions during the recovery from N deprivation. The discussed examples of misregulated pathways (i.e. tetrapyrrole synthesis and peroxisomal redox homeostasis) represent just a fraction of genes affected in their expression by CHT7. Particularly important is that the expression of genes affecting these pathways was completely normal in the cht7 mutant at any other stage outside of N recovery. We hypothesize that when cells receive signals to recover from N deprivation, CHT7 governs some transcriptional programs, directly or indirectly, that allow the resumption of growth and proliferation. This hypothesis can be addressed through the identification of the in vivo chromatin binding sites for CHT7 or CHT7-containing complexes under different growth conditions. A future integrative analysis of the transcriptome and chromatin binding data will help distinguish the genes that are primary or secondary targets of CHT7, as well as clarify the potential feedback regulations by metabolite levels.

Interaction between CHT7 and Other Regulatory Modules of Quiescence

In yeast, the cAMP-PKA pathway is active during abundance of nutrients and represses aspects of nutrient deprivation-induced quiescence by targeting nutrient-sensitive transcription factors MSN2 and MSN4 (Smith et al., 1998; Beck and Hall, 1999). The cAMP signal is also required for a timely recovery, as mutants unable to transiently elevate cAMP levels following the addition of Glc to starved cells show extended delays in resuming growth (Jiang et al., 1998). This is somewhat similar to the observed increase of cAMP following N resupply (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, we showed that PKI-treated PL cells recapitulated both the regrowth and TAG phenotypes of cht7, presumably due to the deactivation of PKA (Fig. 7, B and C). To our surprise, when cht7 cells were treated with nontoxic concentrations of PKI we did not observe deterioration, suggesting some level of functional redundancy between the CHT7 and cAMP-PKA pathways. In adipocytes, adenylyl cyclase and PKA transduce signals between hormone binding to cells and lipolytic responses. Upon activation, PKA phosphorylates hormone-sensitive lipase and perilipin 1 (Guo et al., 2009). This raises the question, whether during the response to N resupply the cAMP-PKA pathway triggers TAG breakdown by phosphorylating protein analogs found in adipocytes, which in turn fuels the recovery or acts on nuclear targets such as CHT7 to stimulate gene expression that promotes growth. Biochemical studies have confirmed the presence of PKA catalytic subunits in C. reinhardtii although the respective genes remain uncertain (Howard et al., 1994). Continued study of cAMP-PKA pathway genes (e.g. the listed candidates in Fig. 7D) will shed light on the role of this pathway in C. reinhardtii quiescence exit.

For the bioindustry using microorganisms to produce drugs, biofuels, nutritional supplements, flavors and fragrances, control of nutrient deprivation-induced quiescence is at the core of research that strives to gain insights into the inverse relationship between biomass production and production of the target compound. Thus, the information gathered here has practical implications for the engineering and cultivation of photosynthetic algae, and potentially more broadly to crop plants. Due to their sessile nature, plants are continuously exposed to biotic and abiotic stresses that prompt cells to arrest growth and division to spare resources for respective defense responses. Understanding how to manipulate the balance between growth versus defense based on insights into the regulation of cellular quiescence may one day help in improving crop yields in agricultural settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Growth Conditions

The Chlamydomonas reinhardtii dw15.1 (cw15, nit1, mt+) or CC-4619 (http://chlamycollection.org/strain/cc-4619-cw15-nit1-mt-dw15-1/) strain was obtained from Arthur Grossman and is referred to as the wild type (with regard to CHT7) PL throughout. A cell-walled strain CC-125 obtained from Chlamydomonas Resource Center (http://www.chlamycollection.org) was used for TEM. The four independent complemented lines of cht7 were generated as previously described (Tsai et al., 2014). Growth conditions and media were as previously described (Tsai et al., 2014). For N deprivation, mid-log-phase cells grown in TAP were collected by centrifugation (2,000g, 4°C, 2 min), washed twice with TAP-N (NH4Cl omitted from TAP), and resuspended in TAP-N at 0.3 OD550. N was resupplied by adding 1% culture volume of 1 m NH4Cl (100×) to the N-deprived culture. The size and concentration of cells in all assays was monitored using a Z2 Coulter Counter.

Lipid Analysis

Lipid extraction, TLC, fatty acid methyl ester preparation, and gas chromatography were conducted as previously described (Tsai et al., 2015) with modifications. For neutral lipids, 5 mL of cell culture was pelleted and extracted into 1 mL of methanol and chloroform (2:1 v/v). To this extract 0.5 mL 0.9% KCL were added and the suspension was vortexed, followed by phase separation at 3,000g centrifugation for 3 min. For polar lipids, 10 mL of culture was extracted with methanol-chloroform-88% formic acid (2:1:0.1 v/v/v) followed by phase separation with 1 m KCl and 0.2 m H3PO4. Lipid species were separated by TLC on Silica G60 plates (EMD Chemicals) developed in petroleum ether-diethyl ether-acetic acid (80:20:1 v/v/v, for neutral lipids) or chloroform-methanol-acetic acid-distilled water (75:13:9:3 v/v/v/v, for polar lipids). After brief exposure to iodine vapor for visualization of lipids, fatty acid methyl esters of each lipid or total cellular lipid were processed and quantified by gas chromatography as previously described (Rossak et al., 1997).

TEM

For electron microscopy, walled strains were fixed and processed as previously described (Harris, 1989), except that TAP medium with or without N was used as diluents for fixatives. Transmission electron micrographs were captured using a JEOL100 CXII instrument (Japan Electron Optics Laboratories).

Metabolite Measurements

Chlorophylls were extracted from fresh cell pellets using 80% acetone, and concentrations were calculated from the absorbance values at 647 and 664 nm according to Zieger and Egle (1965). For the TBARS assay, 5 mL of culture was centrifuged and analyzed immediately. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1 mL of thiobarbituric acid/trichloroacetic acid solution (0.3 and 3.9%, respectively) and heated at 95°C for 15 min. The solution alone was also heated to serve as the blank for spectrophotometric measurements. Samples and blank were measured after no further gas bubbles were released. TBARS were determined by absorbance at 532 and 600 nm as previously described (Baroli et al., 2003). The extinction coefficient used was 155 mm−1 cm−1. Quantification of cellular cAMP was conducted using a cAMP Competitive ELISA kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For some experiments, protein kinase A inhibitor (P9115; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the culture at the time when N was resupplied.

Illumina RNA-Seq and Analysis

The raw data for Illumina RNA-seq were generated in our previous study (Tsai et al., 2014). In each of the experiments, three replicates were taken independently to ensure the reproducibility of the data. RNA abundance in the samples was computed as previously described (Tsai et al., 2014). C. reinhardtii genome sequence and annotations version 5.3.1 were downloaded from JGI (www.phytozome.net/chlamy.php). Differential expression was determined by using the numbers of mapped reads overlapping with annotated C. reinhardtii genes as inputs to DESeq, version 1.10.1 (Anders and Huber, 2010). The hierarchical clustering was conducted and heat maps were generated using Qlucore Omics Explorer (qlucore.com). The quality of the RNA-seq data was also validated by qPCR on select metabolic pathways. To assess which pathway genes tend to be differentially regulated, Fishers exact test was used to determine overrepresentation. Each gene set was compared to each MapMan pathway gene group (http://mapman.gabipd.org/web/guest/mapmanstore, mapmen_Creinhardtii_236, retrieved on 12/11/2014). P values obtained from Fishers exact test were corrected for multiple testing to obtain q-values (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003). Significant overrepresentation was reported for the pathways with q < 0.05. We also repeated the overrepresentation analyses with GO terms. To get GO annotation, we compared Creinhardtii_v5.3_223 peptide sequences available from Phytozome (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html) against the NCBI nonredundant database using blast (BLASTP 2.2.25+). The BLAST results were imported into Blast2Go (version 2.7) and peptides were mapped to GO terms. The resulting overrepresented terms were plotted as heat maps in R using the gplots package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gplots/index.html).

qPCR

qPCR was done as previously described (Tsai et al., 2014) following the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments guidelines (Bustin et al., 2009). All experiments contained at least two biological replicates and each reaction was run with technical repeats. Primers can be found in Supplemental Table S1.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting

To monitor the DNA content in synchronized cells, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) by flow cytometry was carried out as previously described by Fang et al. (2006) with modifications. For this purpose, 10 mL of cells was collected and the cells were fixed by resuspension in 10 mL of 70% ethanol for 1 h at room temperature. Fixed cells were washed once with FACS buffer (0.2 m Tris, pH7.5, 20 mm EDTA, and 5 mm NaN3), resuspended in 1 mL of FACS buffer, and stored at 4°C. Prior to flow cytometry, 2 × 106 of these cells were pelleted, and resuspended in 1 mL of FACS buffer with 100 μg/mL RNase A for 2 h in the dark. Cells were washed with 1 mL of PBS and stained with 1 mL of PI solution (PBS supplemented with 50 μg/mL propidium iodine [Sigma-Aldrich P4864]) overnight in the dark. The samples were then analyzed at the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at the MI State University (http://rtsf.natsci.msu.edu/flow-cytometry/).

Accession Numbers

The filtered sequence data sets have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/) with the BioProject ID PRJNA241455.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Table S1. Oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

Supplemental Figure S1. Experimental setup of RNA-seq experiments.

Supplemental Figure S2. Cell count and size distribution following N resupply.

Supplemental Figure S3. Cellular ultrastructure following N resupply.

Supplemental Figure S4. Confirmation of transcriptional changes by qPCR.

Supplemental Figure S5. Fatty acid composition of cells following N resupply.

Supplemental Figure S6. Polar lipid analysis of cells following N resupply.

Supplemental Figure S7. Fatty acid composition of PKI-treated cells following N resupply.

Supplemental Data Sets. Combined File of Supplemental Data Sets 1 to 11.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Barbara B. Sears and Dr. Ben Lucker for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation (grant no. MCB-1515169) and by MSU AgBioResearch. Additional support was provided by a grant from the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, U.S. Department of Energy (DE-FG02-98ER2035) and National Science Foundation grants DEB-1655386 and IOS-1546617.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Anders S, Huber W (2010) Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11: R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek SH, Li AH, Sassetti CM (2011) Metabolic regulation of mycobacterial growth and antibiotic sensitivity. PLoS Biol 9: e1001065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroli I, Do AD, Yamane T, Niyogi KK (2003) Zeaxanthin accumulation in the absence of a functional xanthophyll cycle protects Chlamydomonas reinhardtii from photooxidative stress. Plant Cell 15: 992–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck T, Hall MN (1999) The TOR signalling pathway controls nuclear localization of nutrient-regulated transcription factors. Nature 402: 689–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisova K, Krylov DM, Umen JG (2005) Genome-wide annotation and expression profiling of cell cycle regulatory genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 137: 475–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaby IK, Glaesener AG, Mettler T, Fitz-Gibbon ST, Gallaher SD, Liu B, Boyle NR, Kropat J, Stitt M, Johnson S, et al. (2013) Systems-level analysis of nitrogen starvation-induced modifications of carbon metabolism in a Chlamydomonas reinhardtii starchless mutant. Plant Cell 25: 4305–4323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bölling C, Fiehn O (2005) Metabolite profiling of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under nutrient deprivation. Plant Physiol 139: 1995–2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botion LM, Green A (1999) Long-term regulation of lipolysis and hormone-sensitive lipase by insulin and glucose. Diabetes 48: 1691–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, et al. (2009) The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55: 611–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castruita M, Casero D, Karpowicz SJ, Kropat J, Vieler A, Hsieh SI, Yan W, Cokus S, Loo JA, Benning C, et al. (2011) Systems biology approach in Chlamydomonas reveals connections between copper nutrition and multiple metabolic steps. Plant Cell 23: 1273–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KD, Dyer JM, Mullen RT (2012) Biogenesis and functions of lipid droplets in plants: Thematic review series: lipid droplet synthesis and metabolism: from yeast to man. J Lipid Res 53: 215–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller HA, Sang L, Roberts JM (2006) A new description of cellular quiescence. PLoS Biol 4: e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J, Deb C, Dubey VS, Sirakova TD, Abomoelak B, Morbidoni HR, Kolattukudy PE (2004) Induction of a novel class of diacylglycerol acyltransferases and triacylglycerol accumulation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis as it goes into a dormancy-like state in culture. J Bacteriol 186: 5017–5030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond PJ. (2007) MONODEHYROASCORBATE REDUCTASE4 is required for seed storage oil hydrolysis and postgerminative growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 1376–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenreich W, Rohdich F, Bacher A (2001) Deoxyxylulose phosphate pathway to terpenoids. Trends Plant Sci 6: 78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang SC, de los Reyes C, Umen JG (2006) Cell size checkpoint control by the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor pathway. PLoS Genet 2: e167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández E, Schnell R, Ranum LP, Hussey SC, Silflow CD, Lefebvre PA (1989) Isolation and characterization of the nitrate reductase structural gene of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 6449–6453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford CA, Ziller MJ, Gu H, Trapnell C, Donaghey J, Tsankov A, Shalek AK, Kelley DR, Shishkin AA, Issner R, et al. (2013) Transcriptional and epigenetic dynamics during specification of human embryonic stem cells. Cell 153: 1149–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroud C, Gerber A, Eichenberger W (1988) Lipids of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii - Analysis of molecular species and intracellular site(s) of biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol 29: 587–595 [Google Scholar]

- Goepfert S, Vidoudez C, Tellgren-Roth C, Delessert S, Hiltunen JK, Poirier Y (2008) Peroxisomal Delta(3),Delta(2)-enoyl CoA isomerases and evolution of cytosolic paralogues in embryophytes. Plant J 56: 728–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Ballester D, Casero D, Cokus S, Pellegrini M, Merchant SS, Grossman AR (2010) RNA-seq analysis of sulfur-deprived Chlamydomonas cells reveals aspects of acclimation critical for cell survival. Plant Cell 22: 2058–2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham IA. (2008) Seed storage oil mobilization. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 115–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JV, Petsko GA, Johnston GC, Ringe D, Singer RA, Werner-Washburne M (2004) “Sleeping beauty”: quiescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68: 187–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Cordes KR, Farese RV Jr, Walther TC (2009) Lipid droplets at a glance. J Cell Sci 122: 749–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EH. (1989) Chlamydomonas Sourcebook. Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- Hemme D, Veyel D, Mühlhaus T, Sommer F, Jüppner J, Unger AK, Sandmann M, Fehrle I, Schönfelder S, Steup M, et al. (2014) Systems-wide analysis of acclimation responses to long-term heat stress and recovery in the photosynthetic model organism Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 26: 4270–4297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman EM, Larkins BA (1999) Protein storage bodies and vacuoles. Plant Cell 11: 601–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka K, Yamashita S (1984) Regulatory role of phosphatidate phosphatase in triacylglycerol synthesis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 796: 110–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DR, Habermacher G, Glass DB, Smith EF, Sale WS (1994) Regulation of Chlamydomonas flagellar dynein by an axonemal protein kinase. J Cell Biol 127: 1683–1692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Sommerfeld M, Jarvis E, Ghirardi M, Posewitz M, Seibert M, Darzins A (2008) Microalgal triacylglycerols as feedstocks for biofuel production: perspectives and advances. Plant J 54: 621–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Davis C, Broach JR (1998) Efficient transition to growth on fermentable carbon sources in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires signaling through the Ras pathway. EMBO J 17: 6942–6951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juergens MT, Disbrow B, Shachar-Hill Y (2016) The relationship of triacylglycerol and starch accumulation to carbon and energy flows during nutrient deprivation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 171: 2445–2457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadouri D, Jurkevitch E, Okon Y, Castro-Sowinski S (2005) Ecological and agricultural significance of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Crit Rev Microbiol 31: 55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klie S, Nikoloski Z (2012) The choice between MapMan and Gene Ontology for automated gene function prediction in plant science. Front Genet 3: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knighton DR, Zheng JH, Ten Eyck LF, Xuong NH, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM (1991) Structure of a peptide inhibitor bound to the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Science 253: 414–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropat J, Hong-Hermesdorf A, Casero D, Ent P, Castruita M, Pellegrini M, Merchant SS, Malasarn D (2011) A revised mineral nutrient supplement increases biomass and growth rate in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J 66: 770–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Benning C, Kuo MH (2012a) Rapid triacylglycerol turnover in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii requires a lipase with broad substrate specificity. Eukaryot Cell 11: 1451–1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Moellering ER, Liu B, Johnny C, Fedewa M, Sears BB, Kuo MH, Benning C (2012b) A galactoglycerolipid lipase is required for triacylglycerol accumulation and survival following nitrogen deprivation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 24: 4670–4686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Beisson Y, Shorrosh B, Beisson F, Andersson MX, Arondel V, Bates PD, Baud S, Bird D, Debono A, Durrett TP, et al. (2013) Acyl-lipid metabolism. Arabidopsis Book 11: e0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie SH, Pringle JR (1980) Reserve carbohydrate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: responses to nutrient limitation. J Bacteriol 143: 1384–1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Vieler A, Li C, Jones AD, Benning C (2013) Triacylglycerol profiling of microalgae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Nannochloropsis oceanica. Bioresour Technol 146: 310–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew T, Zhou W, Rupprecht J, Lim L, Thomas-Hall SR, Doebbe A, Kruse O, Hankamer B, Marx UC, Smith SM, et al. (2009) The metabolome of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii following induction of anaerobic H2 production by sulfur depletion. J Biol Chem 284: 23415–23425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May P, Wienkoop S, Kempa S, Usadel B, Christian N, Rupprecht J, Weiss J, Recuenco-Munoz L, Ebenhöh O, Weckwerth W, et al. (2008) Metabolomics- and proteomics-assisted genome annotation and analysis of the draft metabolic network of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics 179: 157–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant SS, Prochnik SE, Vallon O, Harris EH, Karpowicz SJ, Witman GB, Terry A, Salamov A, Fritz-Laylin LK, Maréchal-Drouard L, et al. (2007) The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science 318: 245–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R, Wu G, Deshpande RR, Vieler A, Gärtner K, Li X, Moellering ER, Zäuner S, Cornish AJ, Liu B, et al. (2010) Changes in transcript abundance in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii following nitrogen deprivation predict diversion of metabolism. Plant Physiol 154: 1737–1752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moellering ER, Benning C (2010) RNA interference silencing of a major lipid droplet protein affects lipid droplet size in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot Cell 9: 97–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HM, Baudet M, Cuiné S, Adriano JM, Barthe D, Billon E, Bruley C, Beisson F, Peltier G, Ferro M, Li-Beisson Y (2011) Proteomic profiling of oil bodies isolated from the unicellular green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: with focus on proteins involved in lipid metabolism. Proteomics 11: 4266–4273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Snell W (2007) The primary cilium: keeper of the key to cell division. Cell 129: 1255–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poxleitner M, Rogers SW, Lacey Samuels A, Browse J, Rogers JC (2006) A role for caleosin in degradation of oil-body storage lipid during seed germination. Plant J 47: 917–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riekhof WR, Sears BB, Benning C (2005) Annotation of genes involved in glycerolipid biosynthesis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: discovery of the betaine lipid synthase BTA1Cr. Eukaryot Cell 4: 242–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittershaus ES, Baek SH, Sassetti CM (2013) The normalcy of dormancy: common themes in microbial quiescence. Cell Host Microbe 13: 643–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossak M, Schäfer A, Xu N, Gage DA, Benning C (1997) Accumulation of sulfoquinovosyl-1-O-dihydroxyacetone in a sulfolipid-deficient mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides inactivated in sqdC. Arch Biochem Biophys 340: 219–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmollinger S, Mühlhaus T, Boyle NR, Blaby IK, Casero D, Mettler T, Moseley JL, Kropat J, Sommer F, Strenkert D, et al. (2014) Nitrogen-sparing mechanisms in Chlamydomonas affect the transcriptome, the proteome, and photosynthetic metabolism. Plant Cell 26: 1410–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siaut M, Cuiné S, Cagnon C, Fessler B, Nguyen M, Carrier P, Beyly A, Beisson F, Triantaphylidès C, Li-Beisson Y, et al. (2011) Oil accumulation in the model green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: characterization, variability between common laboratory strains and relationship with starch reserves. BMC Biotechnol 11: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silljé HH, Paalman JW, ter Schure EG, Olsthoorn SQ, Verkleij AJ, Boonstra J, Verrips CT (1999) Function of trehalose and glycogen in cell cycle progression and cell viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol 181: 396–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirakova TD, Deb C, Daniel J, Singh HD, Maamar H, Dubey VS, Kolattukudy PE (2012) Wax ester synthesis is required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis to enter in vitro dormancy. PLoS One 7: e51641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Ward MP, Garrett S (1998) Yeast PKA represses Msn2p/Msn4p-dependent gene expression to regulate growth, stress response and glycogen accumulation. EMBO J 17: 3556–3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell WJ, Golemis EA (2007) A ciliary timer for S-phase entry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R (2003) Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 9440–9445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoulou FL, Eastmond PJ (2012) Seed storage oil catabolism: a story of give and take. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15: 322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevelein JM, Cauwenberg L, Colombo S, Donation M, Dumortier F, Kraakman L, Lemaire K, Ma P, Nauwelaers D, Rolland F, et al. (2000) Nutrient-induced signal transduction through the protein kinase A pathway and its role in the control of metabolism, stress resistance, and growth in yeast. Enzyme Microb Technol 26: 819–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimm O, Bläsing O, Gibon Y, Nagel A, Meyer S, Krüger P, Selbig J, Müller LA, Rhee SY, Stitt M (2004) MAPMAN: a user-driven tool to display genomics data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. Plant J 37: 914–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MP, Liu X, Whangbo J, McCrossan G, Sanborn KB, Basar E, Walch M, Lieberman J (2015) Apoptosis triggers specific, rapid, and global mRNA decay with 3′ uridylated intermediates degraded by DIS3L2. Cell Reports 11: 1079–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CH, Warakanont J, Takeuchi T, Sears BB, Moellering ER, Benning C (2014) The protein Compromised Hydrolysis of Triacylglycerols 7 (CHT7) acts as a repressor of cellular quiescence in Chlamydomonas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 15833–15838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CH, Zienkiewicz K, Amstutz CL, Brink BG, Warakanont J, Roston R, Benning C (2015) Dynamics of protein and polar lipid recruitment during lipid droplet assembly in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J 83: 650–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcourt JR, Lemons JM, Haley EM, Kojima M, Demuren OO, Coller HA (2012) Staying alive: metabolic adaptations to quiescence. Cell Cycle 11: 1680–1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zutphen T, Todde V, de Boer R, Kreim M, Hofbauer HF, Wolinski H, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ, Kohlwein SD (2014) Lipid droplet autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 25: 290–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZT, Ullrich N, Joo S, Waffenschmidt S, Goodenough U (2009) Algal lipid bodies: stress induction, purification, and biochemical characterization in wild-type and starchless Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot Cell 8: 1856–1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wase N, Black PN, Stanley BA, DiRusso CC (2014) Integrated quantitative analysis of nitrogen stress response in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii using metabolite and protein profiling. J Proteome Res 13: 1373–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildwater M, Campilho A, Perez-Perez JM, Heidstra R, Blilou I, Korthout H, Chatterjee J, Mariconti L, Gruissem W, Scheres B (2005) The RETINOBLASTOMA-RELATED gene regulates stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis roots. Cell 123: 1337–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Work VH, Radakovits R, Jinkerson RE, Meuser JE, Elliott LG, Vinyard DJ, Laurens LM, Dismukes GC, Posewitz MC (2010) Increased lipid accumulation in the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii sta7-10 starchless isoamylase mutant and increased carbohydrate synthesis in complemented strains. Eukaryot Cell 9: 1251–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Zhang N, Hayes A, Panoutsopoulou K, Oliver SG (2004) Global analysis of nutrient control of gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during growth and starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 3148–3153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Yu X, Song L, An C (2011) ABI4 activates DGAT1 expression in Arabidopsis seedlings during nitrogen deficiency. Plant Physiol 156: 873–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieger R, Egle K (1965) Zur quantitativen Analyse der Chloroplasten pigmente. I. Kritische Überprüfung der spektralphotometrischen Chlorophyllbestimmung. Beitr Biol Pflanz 41: 11–37 [Google Scholar]

- Zones JM, Blaby IK, Merchant SS, Umen JG (2015) High-resolution profiling of a synchronized diurnal transcriptome from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii reveals continuous cell and metabolic differentiation. Plant Cell 27: 2743–2769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]