Abstract

Background:

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is one of the leading causes of death and physical disability worldwide. However, the development of community- based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) in AMI patients is hysteretic. Here, we aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of CR applied in the community in AMI patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods:

A total of 130 ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients after PCI were randomly divided into 2 groups in the community, rehabilitation group (n = 65) and control group (n = 65). Cardiac function, a 6-minute walk distance, exercise time and steps, cardiovascular risk factors were monitored respectively and compared before and after the intervention of 2 groups. The software of EpiData 3.1 was used to input research data and SPSS16.0 was used for statistical analysis.

Results:

After a planned rehabilitation intervention, the rehabilitation group showed better results than the control group. The rehabilitation group had a significant improvement in recurrence angina and readmission (P < .01). Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of rehabilitation group showed improvement in phase II (t = 4.963, P < .01) and phase III (t = 11.802, P < .01), and the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification was recovered within class II. There was a significant difference compared with before (Z = 7.238, P < .01). Six minutes walking distance, aerobic exercise time, and steps all achieved rehabilitation requirements in rehabilitation group in phase II and III, there existed distinct variation between 2 phases. Rehabilitation group had a better result in cardiovascular risk factors than control group (P < .05).

Conclusion:

Community-based CR after PCI through simple but safe exercise methods can improve the AMI patient's living quality, which includes increasing cardiac ejection fraction, exercise tolerance, and physical status. It must be emphasized that the good result should be established by the foundation of close cooperation between cardiologists and general practitioners, also the importance of cooperation of patients and their families should not be ignored. The rehabilitation program we used is feasible, safe, and effective.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, cardiac rehabilitation, community

1. Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is not only a severe type of coronary heart disease (CHD), but also one of the leading causes of death and physical disability, particularly in the rapidly growing population of elderly persons.[1] Although the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) reduced the mortality, enabling discharged patients to restore their health, and return to the society is still a public health problem to be solved in the current situation.[2]

Community-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) shows to be a cost-effective intervention and an indispensable component of the canonical rehabilitation.[3] At present, CR is still the short board in the overall treatment of CHD. The development of community-based CR in AMI patients is still unsatisfactory, <25% of outpatients have been reported to enroll in CR, with <10% in elderly patients,[4] within this small number of patients participating in CR, 30% to 40% of patients discontinued CR after 6 months, with up to 50% dropping out after 1 year.[5] The aim of this study was to explore exercise rehabilitation program's safety, effectiveness, and feasibility and to establish a simple and operable technology which can be carried out by general practitioners (GPs) in AMI patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

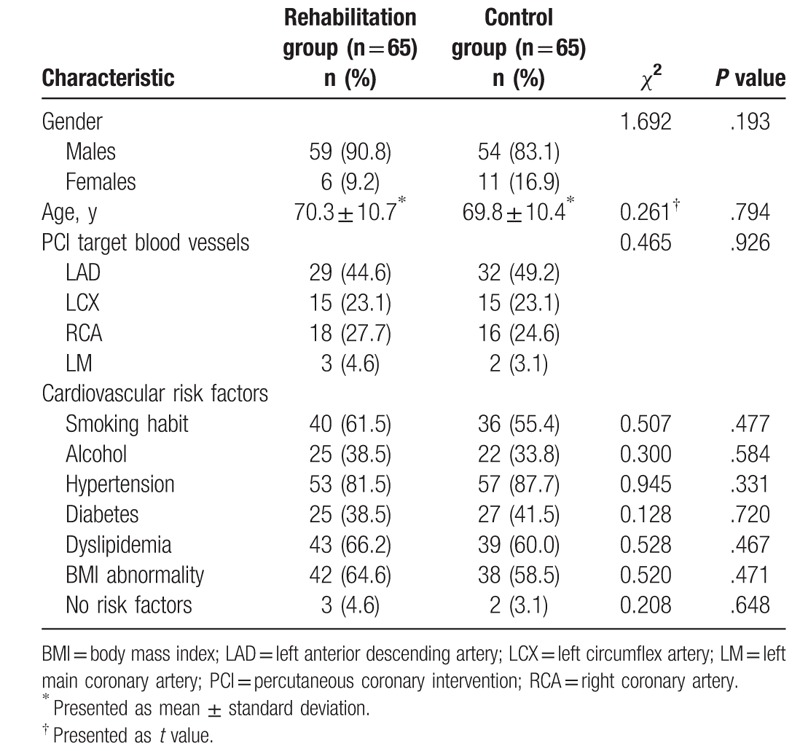

We enrolled 130 consecutive patients (17 women and 113 men, age 45–81 years, mean age 70.1 years) whom were admitted to the outpatient clinic after successful PCI for ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) between January 2010 and December 2012. They were excluded in both groups if they had[6]: the large area of myocardial infarction, heart failure, acute systemic illness, systolic blood pressure (BP) >180 mmHg at rest, diastolic BP >110 mmHg at rest, acute metabolic disorders, uncontrolled malignant arrhythmia, and skeletal vascular disease. The patients who refused to give their informed consent to the exercise program were excluded in both groups. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants. All included patients had no obvious difference in age and gender (P > .05). The general data of 2 groups of patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline differences between rehabilitation and control groups.

2.2. Exercise training program

The community-based CR was regularly supervised by GPs. The control group was given the usual care and conventional drug therapy after PCI. The examinational group was given the CR on the basis of the routine therapy. GPs formulated individualized program of aerobic exercise, which depended on the patients’ clinical condition and the cardiovascular risk stratification. CR could be performed on outpatients at their homes or at specialized rehabilitation facilities in the community. This could be supervised by GPs and accompanied by family members. Phase II CR should be optimally initiated at the second week after patients were discharged, which had 2 courses, each course required 3 to 4 weeks. The most available and simple form of exercise was walking, however, other forms of aerobic exercises were acceptable. The following approaches were used in CR to set the acceptable workload: heart rate (HR) was acceptable lower than 130 bpm or resting HR plus 30 bpm, exercise intensity could be measured subjectively by the Borg scale. The recommended rating of perceived exertion (RPE) score was no more than 11 to 15, from the beginning 50 kcal/time to the next course 250 to 300 kcal/time. The patients should exercise 2 to 3 times/wk, they could take interval or continuous training for 15 to 30 minutes. Regardless of the form of physical activity, the main training session of phase II and III would start following a 10-min warm-up, and finish with a 10-min cool-down exercise. HR, BP, energy consumption, movement distance, and RPE were supervised by the GPs before and after the exercise. Phase III started from the 3rd month to 1 year (in our study the endpoint was the 6th month). The target HR was 60% to 75% of the maximal HR, the RPE score was no more than 12 to 16, and exercise intensity was 300 to 400 kcal/time. The intensity was 30 to 45 min/time, not less than 3 to 5 times a week. Phase II and III exercise should be terminated or modified if the patient had any uncomfortable symptoms.[6] In this study, we monitored the exercise capacity by a 6-minute walk test (6-MWT) in rehabilitation group, by using a pedometer (model for Japanese omron MBB-HJ-105) to record the total effective steps, the distance, and the calories (kcal). Out-of-hospital early rehabilitation (Phase II, end of 2nd month): started from the second week after discharge from hospital, for a total of 2 courses, 1 course lasting 3 to 4 weeks; out-of-hospital late rehabilitation (Phase III, end of 6th month): started from the 3rd month to the 6th month. We examined the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by the echocardiography and detected the cardiovascular risk factors, including body mass index (BMI), BP, lipid, blood sugar (BS) levels, myocardial necrosis markers in the course of 2nd month (phase II) and 6th month (phase III).

2.3. Statistical analysis

EpiData 3.1 (The Epidata Association, Odense, Denmark) statistical software was used for database design and data entry. Data were reported as mean and standard deviation. Within-group and between-group analyses were performed. Measurement data between groups were analyzed using the t test, one-way analysis of variance or repeated measures analysis of variance. Comparison of categorical variables was generated by the Pearson χ2 test. Statistical comparisons were performed using SPSS, version 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The data of the same group before and after the intervention were compared using paired t test, paired χ2 test or paired rank sum test. The results were considered statistically significant at a P < .05.

3. Results

3.1. All 130 subjects completed the study

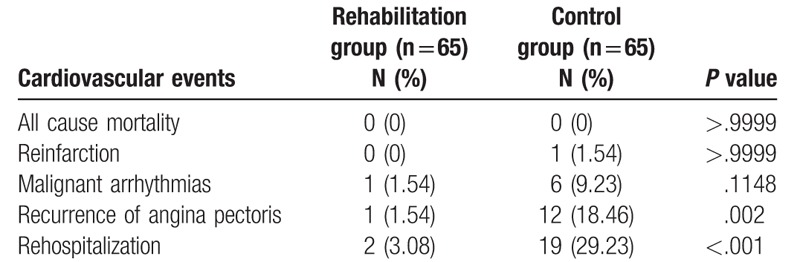

As shown in Table 2, no significant differences were found between the 2 groups in terms of all causes mortality, reinfarction, and malignant arrhythmia (P > .05). Compared with the control group, patients in the rehabilitation group experienced less post infarction angina (P = .002), and a lower rehospitalization rate (P < .001).

Table 2.

Comparison of the cardiovascular event incidence in 2 groups.

3.2. Comparison of the 2 groups with heart function

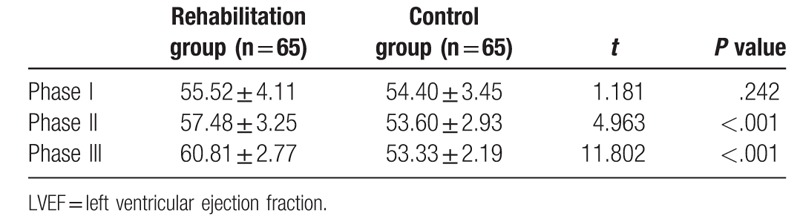

3.2.1. Results of echocardiography between the 2 groups

No significant difference was shown in the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) between the 2 groups when they were discharged. The LVEF of patients from rehabilitation group significantly increased compared with control group after rehabilitation, the repetitive measure analysis of variance was used, the results showed that different rehabilitation periods existed significant differences in the rehabilitation group (F = 20.26, P < .05), whereas there was no significant difference in the control group (F = 1.097, P > 1.097) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of LVEF in 2 groups.

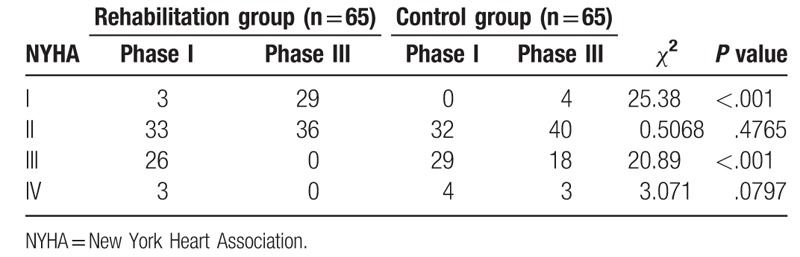

3.2.2. Comparison of the 2 groups in NYHA classification

Before cardiac rehabilitation, the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification of most of the patients from the 2 groups was below class III, some individual patients were classified as class IV, 3 cases in the rehabilitation group and 4 cases in the control group. After comprehensive rehabilitation, the patients in the rehabilitation group were all restored to class II, the difference was statistically significant compared with before (Z = 7.238, P < .001). Meanwhile, the NYHA classification of patients form control group also achieved improvement (Z = 4.123, P < .001) compared with former result, but there were still 3 cases classified as class IV, 18 cases of class III (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the NYHA classification in 2 groups.

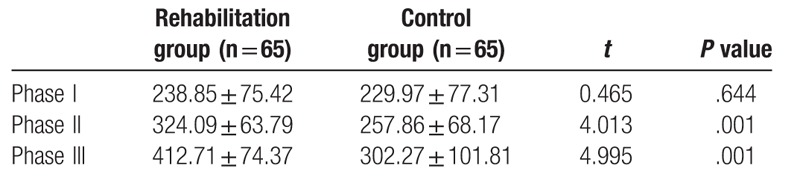

3.3. Results of 6-MWT of the 2 groups

Before cardiac rehabilitation, there was no significant difference in 6-MWT between the 2 groups. After the intervention, the rehabilitation group made a faster progress than the control group in the walking distance in phase II and III, significant differences were found between the phases (Table 5). Repeated measures analysis of variance showed that walking distances of the 2 groups all obviously increased. However, during different phase, the 2 groups showed significant difference in walking distance which was more obvious in the rehabilitation group (F = 50.414, P < .001).

Table 5.

Comparison of the 6 minutes walking distance in 2 groups.

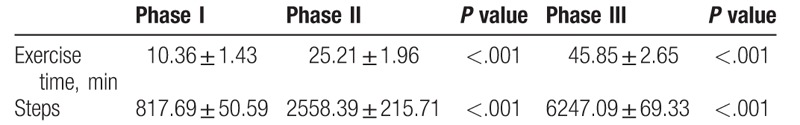

3.4. Results of pedometer records of rehabilitation group

The rehabilitation group recorded the patients’ steps and walking time to observe exercise intensity and progress at different time by using a pedometer. Before rehabilitation intervention, patients’ aerobic exercise time and walking distances were all short. After the rehabilitation, during phase II and III, the steps increased gradually to reach the exercise requirements (Table 6). Repeated measures analysis of variance showed significant differences in walking time and steps between different phases (P < .001).

Table 6.

Comparison of the exercise time and the number of steps in different periods.

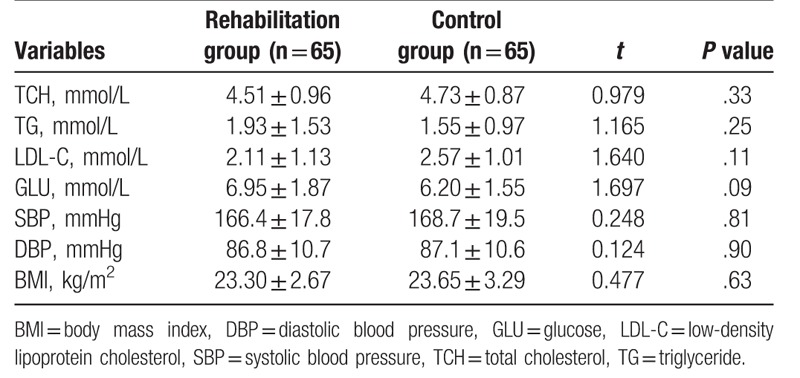

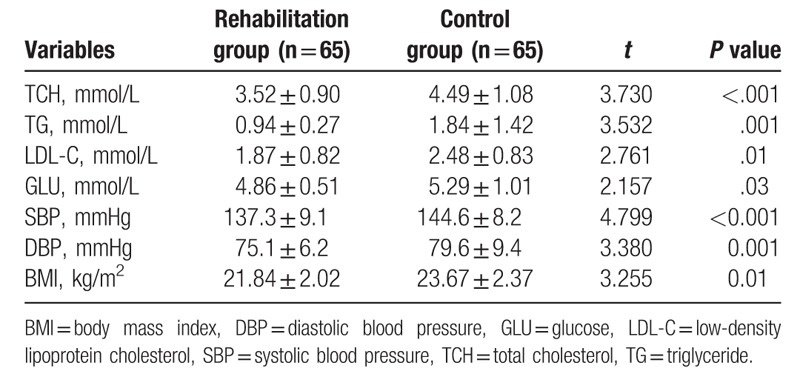

3.5. Comparison of cardiovascular risk factors

When discharged, 2 groups of patients had no significant differences in BMI, BP, BS, lipids, and other clinical indicators. After the rehabilitation, those indicators of patients from the rehabilitation group had significantly improved compared with control group (P < .05) (Tables 7 and 8).

Table 7.

Comparison of cardiovascular risk factors in 2 groups before rehabilitation.

Table 8.

Comparison of cardiovascular risk factors in 2 groups after rehabilitation.

3.6. Comparison of 2 groups with myocardial necrosis markers

There was no statistical difference of creatine kinase (CK) and its isoenzyme MB (CKMB), cardiac troponin-I (cTnI), C-reactive protein (CRP) between the 2 groups, and the myocardial necrosis markers were all in the normal range during the period.

4. Discussion

The treatment of AMI has reached a higher level, but the CR is still hysteretic in the whole treatment, and the studies on community rehabilitation are rarely reported. After 50 years of research and development, the benefit of CR was now fully supported by clinical research evidence. Meta-analysis confirmed that exercise-based CR was associated with significant reductions in cardiac mortality, post-MI reinfarction, and all cause mortality.[7–10] Mortality was negatively correlated with the participation time of rehabilitation. As an independent intervention factor after myocardial infarction, CR can reduce the incidence of cardiac events and mortality, significantly improve patient's body function (e.g., vo2 Max)[11,12] and their quality of life.[13,14]

The conception of CR has been gradually applied in clinical treatment. It was clearly put forward in the 5 prescriptions in Chinese expert consensus about rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease,[15] which was consisted of medication, exercise, psychological counseling, education, and smoking cessation. As a core part, exercise rehabilitation has many advantages, such as reducing the vascular inflammation,[16] enhancing vascular endothelial function, and increasing the coronary collateral blood flow.[17,18] It has been confirmed that exercise rehabilitation could significantly reduce the incidence of in-stent restenosis for AMI patients who underwent PCI.[19] Community-based rehabilitation supervised by GPs is not widely used because of lacking in convenient and feasible technology. This study was to explore possible ways to be carried out in the community. The pedometer method was implemented for exercise rehabilitation with quantitative monitoring, the 6-MWT and the RPE index were used to evaluate AMI patients’ exercise capacity. The formulation of exercise prescription was based on the evaluation of risk stratification of CHD, heart function, physical storage, and the general condition of the patients and their preferences. Through phase II and III of exercise rehabilitation, the LVEF and NYHA classification were significantly improved.

6-MWT is safe, reliable, and also has practical value. It is an objective examination to evaluate the exercise tolerance and exercise capacity of AMI patients in the community, and it can assess the extent of patients’ recovery during the rehabilitation.[20] Instead of using the submaximal exercise test, the low power 6-MWT is simpler and safer which is more similar to the patients’ daily activities and encourage more patients to take part in. Our study was a community-based rehabilitation program, so the technical monitoring method was based on the implementation of the conditions, the level of health services and patients’ health situation. Therefore, 6-MWT and the RPE index were used to evaluate AMI patients’ exercise capacity and the methods were used to guide the rehabilitation. The results of this study reflected the patients’ physical changes after the rehabilitation, and cardiac adverse events did not occur in the trial. Therefore, we believed that this method could be used to evaluate the cardiac function and physical fitness under close monitoring, and to guide the formulation and adjustment for the exercise prescription.

Walking is the most popular, basic, and important physical activity. The Pedometer is the most important tool as an intervention to heighten physical activities. Pedometer can record the steps in a day, and convert the data to corresponding kilometer and consumed energy. Patients can know their rehabilitation progress with the help of a pedometer. They can adjust exercise intensity and increase the confidence of rehabilitation. Besides, it can also help the GPs to improve the exercise rehabilitation plans. In this study, it showed that patients could easily use the pedometer, and the results reflected patients’ physical improvement. By using pedometer, AMI patients could set up their own rehabilitation plans and supervise themselves to take part in physical activities.

After this study, we found improvements of BP and BMI in rehabilitation group compared with control group, but they all had improvement in BS. Compared the effect of secondary prevention between 2 groups, rehabilitation group was better than control group. The result has close relation with the exercise rehabilitation. Although the exercise intensity of rehabilitation group was not vigorous, it was good for reducing cardiovascular risk factors. We also can’t deny the important impact of comprehensive intervention in controlling the cardiovascular risk factors, such as health education and nutrition guidance. Therefore, we should pay more attention to use multiple measures in CR. In a word, comprehensive rehabilitation including exercise, health education, and psychology rehabilitation are all absolutely necessary.[21]

Above all, the community-based CR for AMI patients can improve cardiac ejection fraction, increase exercise tolerance, improve the patient's physical status, reduce cardiovascular risk factors. It must be emphasized that the good result should be established by the foundation of close cooperation between cardiologists and general practitioners, also the importance of cooperation of patients and their families should not be ignored. In this study the use of pedometer and 6-MWT is safe and effective, the feasibility is high by GPs in the community, it can be used as an important part of the overall treatment for myocardial infarction. The sample of this study is small, problems such as the insufficiency of health education and the training of GPs still exist, we expect more studies with large samples and multicenters of CR program to promote and improve the community-based rehabilitation program.

Treatment of AMI patients has always been the spotlight-subject. By strengthening the operability of the community rehabilitation, popularizing the application of appropriate technology, collaborating with cardiologists and community general practitioners,[22] we can develop the continuity of rehabilitation for AMI patients to improve their prognosis, help them have a better quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere appreciation to the study participants.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 6-MWT = 6-minute walk test, AMI = acute myocardial infarction, BMI = body mass index, BP = blood pressure, BS = blood sugar, CHD = coronary heart disease, CK = creatine kinase, CKMB = creatine kinase isoenzyme MB, CR = cardiac rehabilitation, CRP = C-reactive protein, cTnI = cardiac troponin-I, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, GLU = glucose, GPs = general practitioners, HR = heart rate, LAD = left anterior descending artery, LCX = left circumflex artery, LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LM = left main coronary artery, LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA = New York Heart Association, PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention, RCA = right coronary artery, RPE = rating of perceived exertion, SBP = systolic blood pressure, STEMI = ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction, TCH = total cholesterol, TG = triglyceride.

YZ and HXC have equal contributions.

This study was supported by Research Project for practice Development of National TCM Clinical Research Bases (JDZX2015133).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Leon AS, Franklin BA, Costa F, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2001;345:892–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hu DY. Exploring the cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention model for rejoining the fragmented medical services chain. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2012;51:667–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Perk J, Graham I. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012): the fifth joint task force of the european society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2012;19:585–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wolkanin-Bartnik J, Pogorzelska H, Bartnik A. Patient education and quality of home-based rehabilitation in patients older than 60 years after acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2011;31:249–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Salvetti XM, Oliveira JA, Servantes DM, et al. How much do the benefits cost? Effects of a home-based training programme on cardiovascular fitness, quality of life, programme cost and adherence for patients with coronary disease. Clin Rehabil 2008;22:987–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ruano-Ravina A, Pena-Gil C, Abu-Assi E, et al. Participation and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs. A systematic review. Int J Cardiol 2016;223:436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lawler PR, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Efficacy of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation post-myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J 2011;162:571.e2–84.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Suaya JA, Stason WB, Ades PA, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and survival in older coronary patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hammill BG, Curtis LH, Schulman KA, et al. Relationship between cardiac rehabilitation and long-term risks of death and myocardial infarction among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Circulation 2009;121:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Goel K, Lennon RJ, Tilbury RT, et al. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation on mortality and cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 2011;123:2344–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fukuda T, Kurano M, Fukumura K, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation increases exercise capacity with a reduction of oxidative stress. Korean Circ J 2013;43:481–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Benetti M, Araujo CL, Santos RZ. Cardiorespiratory fitness and quality of life at different exercise intensities after myocardial infarction. Arq Bras Cardiol 2010;95:399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Moholdt T, Aamot IL, Granøien I, et al. Aerobic interval training increases peak oxygen uptake more than usual care exercise training in myocardial infarction patients: a randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil 2012;26:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Marzieh S, Samaneh M, Hosein H, et al. Effects of a comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation program on quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. ARYA Atheroscler 2013;9:179–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chinese Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association. Chinese experts consensus on cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention for coronary artery disease. Chin J Cardiol 2013;41:267–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Aminlari A, Jazayeri SM, Bakhshandeh AR. Association of cardiac rehabilitation with improvement in high sensitive C-reactive protein post-myocardial infarction. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2012;14:49–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hotta K, Kamiya K, Shimizu R, et al. Stretching exercises enhance vascular endothelial function and improve peripheral circulation in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int Heart J 2013;54:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cesari F, Marcucci R, Gori AM, et al. Impact of a cardiac rehabilitation program and inflammatory state on endothelial progenitor cells in acute coronary syndrome patients. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:1854–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lee HY, Kim JH, Kim BO, et al. Regular exercise training reduces coronary restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:2617–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bellet RN, Adams L, Morris NR. The 6-minute walk test in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation: validity, reliability and responsiveness—a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2012;98:277–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Smith SC, Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2432–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cupples ME, Tully MA, Dempster M, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation uptake following myocardial infarction: cross-sectional study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:431–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]