Abstract

Objective

We investigated potential effects of increased African American participation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) clinical trials by examining differences in comorbid conditions and treatment outcome affecting trial design.

Methods

Using a meta-database of 18 studies from the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, we included a cohort of 5,164 subjects for whom there were baseline demographic data and information on comorbid disorders, grouped by organ system. We used meta-analysis to compare prevalence of comorbidities, dropouts, and rates of change on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog) by race. We also simulated clinical trial scenarios similar to recent therapeutic trials to determine effects of increased African American participation on statistical power.

Results

Approximately 7% of AD, 4% of MCI, and 11% of normal participants were African American. African American subjects had higher prevalence of cardiovascular disorders (odds ratio [OR] 2.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.71, 2.57) and higher rate of dropouts (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.15, 2.21) compared to whites, but lower rates of other disorders. There were no significant differences in rate of progression (−0.862 points/year, 95% CI −1.89, 0.162) by race, and little effect on power in simulated trials with sample sizes similar to current AD trial designs.

Conclusions

Increasing African American participation in AD clinical trials will require adaptation of trial protocols to address comorbidities and dropouts. However, increased diversity is unlikely to negatively affect trial outcomes and should be encouraged to promote generalizability of trial results.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, clinical trial design, racial differences, diversity

INTRODUCTION

African Americans constitute approximately 9% of the elderly population in the United States, but the percentage of minority subjects in clinical trials of therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has consistently been less than 5%.(1) Investigators may view African American participants as sufficiently different from other participants that they impact the efficiency, outcomes, and validity of clinical trial enrollment. Such beliefs may be implicit in nature,(2) although this issue has not been specifically examined in the context of clinical trials. One example would be the belief that African American subjects are more likely to have cardiac disease, hypertension, and other comorbidities that may affect trial validity.(3) Selection criteria based on these conditions, as well as demographic characteristics such as education, disproportionately exclude potential African American subjects.(4, 5) Other examples would be the belief that African American participants may be more likely to discontinue treatment, or that relative lack of instruments with race- and education-adjusted normative data may lead to increased trial variability, making detection of therapeutic effects more difficult.(6, 7) Whether differences exist between African American and white participants in AD clinical trials cannot be tested retrospectively by examining individual trials because there are too few African American subjects in any one trial to perform post hoc model-based subanalyses. This study utilized meta-analysis of a meta-database of AD clinical trials and observational studies, having over 5100 subjects with approximately 350 African Americans to overcome limitations of individual studies, examining differences in medical comorbidity and dropout rate between African Americans and whites and their effect on outcomes in AD clinical trials.

METHODS

Study Overview and Subjects

Subjects were drawn from a meta-database(8) consisting of 18 studies from the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS)(9) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI),(10) representing both clinical trials and observational studies in AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and normal participants (National Institutes of Health grant R01 AG037561; Supplemental Table 1). All diagnoses of AD were based on NINDS-ARDRA criteria,(11) with the additional requirement of minimal severity based on clinical ratings. Diagnosis of MCI required a Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) score of 0.5 with the memory box scored at 0.5 or greater, and delayed recall from the Logical Memory II subscale of the Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised(12) to be ≤ 8 for 16 years of education, ≤ 4 for 8–15 years, or ≤ 2 for 0–7 years. Patients had to be largely intact with regard to general cognition and functional performance, and could not qualify for a dementia diagnosis. Subjects with AD or MCI in most trials analyzed could continue using marketed anti-dementia drugs if they had been on stable doses prior to entry, and were not excluded from simulations. Clinical assessments were done at 6-month intervals over the first 2 years.

Outcomes

Medical Comorbidities

Prevalence of comorbid medical disorders at baseline among trial subjects was determined from lists of conditions collected by the individual studies. Analyses were restricted to 17 of the 18 studies in which African American subjects were enrolled. Comorbidities were mapped to 19 categories (psychiatric; neurologic [other than AD]; head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat [HEENT]; cardiovascular; respiratory; hepatic; dermatologic-connective tissue; musculoskeletal; endocrine-metabolic; gastrointestinal; hematopoietic-lymphatic; renal-genitourinary; allergies or drug sensitivities; alcohol abuse; drug abuse; smoking; malignancy; major surgical procedures; and other) currently in use by ADNI and classified as present or absent.

Dropout Rates

Dropouts were defined as the number of subjects missing the final study visit, regardless of study duration, as studies being analyzed have different lengths. Most studies included in the analysis did not distinguish between death and dropout for other reasons. Analyses were restricted to 10 studies of AD or MCI with the ADAS-cog as primary outcome and duration of at least 12 months.

Cognition

Cognitive assessments were performed using the ADAS-cog,(13) which evaluates memory, reasoning, orientation, praxis, language, and word finding difficulty, and is scored from 0 to 70 errors. Analyses were restricted to 11 studies of AD or MCI with the ADAS-cog as primary outcome and duration of at least 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

An exact fixed effects meta-analysis model was fit to individual studies to derive overall prevalence of comorbid medical conditions for the two racial groups (white and African American) due to the small number of subjects with many conditions. A random effects meta-analysis model was used to derive overall dropout rates among subjects. Funnel plots were used to assess for evidence of systematic bias,(14) and study heterogeneity was quantified using Cochran’s Q test.(15) The random effects model was used as it is preferred over the fixed effects model when significant heterogeneity is present.(16) Weighting by sample size was used to avoid excessive influence of smaller studies.

Rates of cognitive decline were estimated using mixed effects linear models(17) to test for differences in slopes (rates of change) of the ADAS-cog between the two racial groups. The mixed effects model was employed as it utilizes data from all subjects (rather than just completers), minimizes bias, and better controls for Type I error in the presence of missing data.(18) A full model was constructed with group and time effects and group by time interactions, with age as a covariate, and a reduced model with time, group, and age effects. Thus, for subject i = 1,2, …, n at time j = 1,2, …, ni, the full model was

and the reduced model was

where the model includes both fixed effects of time at the group level and random effects of time at the individual level. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to model independence of the slope and intercept parameters. Parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood. P-values for the group (race) by time interaction were found using −2 times the difference in the log likelihood of the full and reduced model, which follows a chi-squared distribution. Estimated rates of progression for African Americans relative to whites in individual trials were combined using random effects meta-analysis to determine the overall effect of race on cognitive decline.

Clinical Trial Simulations

Simulations were conducted under a detailed protocol,(19) similar to our previously published approach,(8, 20) to reflect typical clinical trials of an experimental drug for amnestic MCI or AD with one treatment and placebo group, 1:1 allocation ratio, and parameters selected to be consistent with previously published trials(21, 22) and ADNI. This simulation approach allows for construction of clinical trials that are not identical to the original studies, but are expected to reflect the subject composition of future clinical trials as well.

For each trial scenario, a separate set of subjects was constructed by randomly choosing from the meta-database with replacement, i.e., subjects could be present in simulated groups more than once. Resampling was performed separately within African American and white subjects so that the percentage of African American subjects in simulated studies would range from 20% to 80%. Sample sizes of 25 to 400 per treatment arm were used; 12, 18, and 24 month long trials were considered; and the ADAS-cog was the primary outcome. Both the placebo group and treatment group from the original trials were included in simulating placebo subjects, as no treatment effect was found in the original trials. The placebo group outcome was the score for the subject at the specified time point in the meta-database, with random error of mean 0 and standard deviation 1 added so that individuals in the simulation more than once would not have identical scores. For the treatment group, a range of effect sizes from 0.15 to 0.55 in 0.10 increments were used to compute an expected treatment effect (slowing of decline) reflecting very small to moderate effect sizes.(23) For each patient, an individual treatment effect was randomly generated from a chi-square distribution with mean equal to the expected treatment effect. The outcome was rounded to the nearest 1/3 point to yield plausible ADAS-cog scores. Dropout rates of 20% and 40% were incorporated into the scenarios. For all analyses, the missing data pattern present in the meta-database was used to realistically simulate dropouts; observations were missing in simulated datasets if they were originally missing in the meta-database. This approach would minimize bias arising from differential dropout among groups.(24)

Power was calculated as the proportion of 10,000 simulated trials per trial scenario having a p-value ≤ 0.05 for the treatment by time interaction in mixed model analysis. Analyses were performed using version 3.1.2 of the R programming environment.(25) Mixed model analyses were performed using version 1.1–7 of the lme4 package for R,(26) and meta-analyses were performed using the exactmeta(27) and metafor(28) packages for R.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All procedures for the original studies were approved by local institutional review boards. The analyses for this study were exempted from informed consent requirements by the IRB.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Across 17 studies, there were 5,164 subjects, with 7% of AD subjects, 4% of MCI subjects, and 11% of normal participants being African American (Table 2). African American subjects had similar age to white subjects, but differed significantly from whites on other key demographics, including a higher proportion with lower education, who were widowed or divorced, and were female.

For both AD and normal comparison groups, African Americans had similar performance as whites on the ADAS-cog at baseline and all subsequent time points. The variability (standard deviation) was similar for African Americans and whites with AD, while African Americans had higher variability than whites in the comparison group. For MCI, African Americans had lower scores on the ADAS-cog across time points, although this only reached statistical significance at 18 months. The variability among African Americans with MCI was lower than whites with MCI.

Outcomes

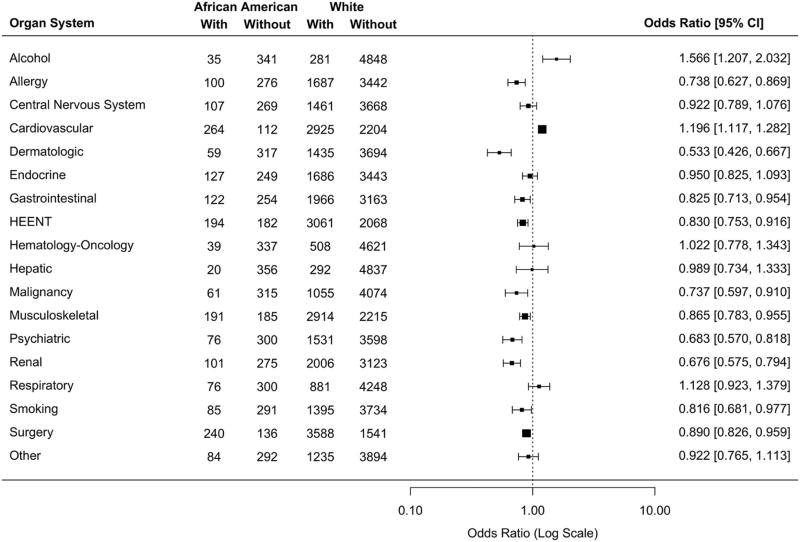

Meta-analysis of baseline prevalence of medical comorbidities in African Americans relative to whites across 17 studies is shown in Figure 1. The former had higher risk of cardiovascular disorders than the latter. African Americans had a lower risk of many disorders, including allergy, dermatologic, gastrointestinal, HEENT, malignancy, musculoskeletal, psychiatric, renal, smoking, and surgery. For alcohol-related disorders, the number of African American subjects was likely too small for firm conclusions.

Figure 1. Forest plot of the prevalence of medical comorbidities in African Americans relative to whites at baseline, grouped by organ system.

Estimates from individual studies were combined using an exact fixed effects meta-analytic model, with 95% confidence intervals obtained by bootstrapping with 20,000 bootstrap samples. Two studies with no African American participants (PIWEB, SIN) were excluded from analysis. Two studies coded hysterectomy separately, which was combined with other surgeries for this analysis. Similarly, three studies coded drug abuse separately, which was combined with psychiatric disorders for this analysis. HEENT=Head, eye, ear, nose, and throat (otorhinolaryngological).

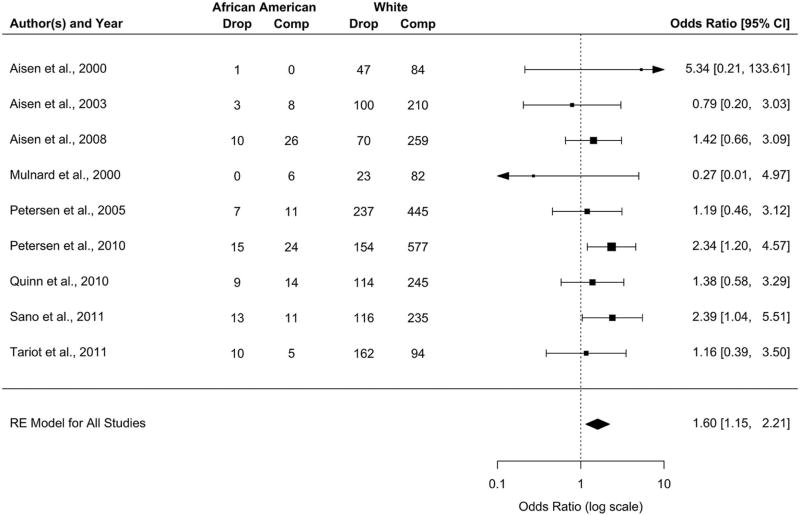

The overall dropout rate was 39.5% (Wald 95% CI [28.4%, 50.7%]) for African Americans and 36.6% (Wald 95% CI [26.0%, 47.3%]) for whites. Dropout rates remained higher for African Americans when results were broken down by disease severity. For AD, the rate for African Americans was 41.0% (Wald 95% CI [27.5%, 54.5%]) and for whites 37.6% (Wald 95% CI [26.0%, 49.2%]); for MCI, the rate for African Americans was 36.3% (Wald 95% CI [19.9%, 52.6%]) and for whites 29.6% (Wald 95% CI [19.4%, 39.8%]). Meta-analysis of the odds of dropouts across 9 studies is shown in Figure 2. Compared to whites, African Americans had a 60% greater risk of missing the final study visit (OR 1.60, Wald 95% CI [1.15, 2.21]), which was statistically significant. The test of heterogeneity was not significant (Q=11.156, df=8, p=0.193), but Cochran’s Q can often fail to achieve significance with a small number of studies. A funnel plot generally showed a high level of precision among the studies, but did identify one study (SL) as an outlier (Supplemental Figure 1a). This study, which had lower dropout in African Americans (OR 0.448, Wald 95% CI [0.175, 1.143]), was excluded from the analysis in Figure 2. Inclusion of this study in the meta-analysis would attenuate risk for African Americans to where it was no longer statistically significant (OR 1.327, Wald 95% CI [0.899, 1.959]).

Figure 2. Forest plot of dropout rates in African Americans relative to whites.

Dropouts were defined as subjects missing the final study assessment on the ADAS-cog, regardless of study duration. Estimates for individual studies are the odds ratio for dropout among African Americans and the associated Wald-type 95% confidence interval (CI). Estimates were combined using a random-effects (RE) meta-analytic model with restricted maximum likelihood (REML). One study (SL) was identified as an outlier and excluded from analysis.

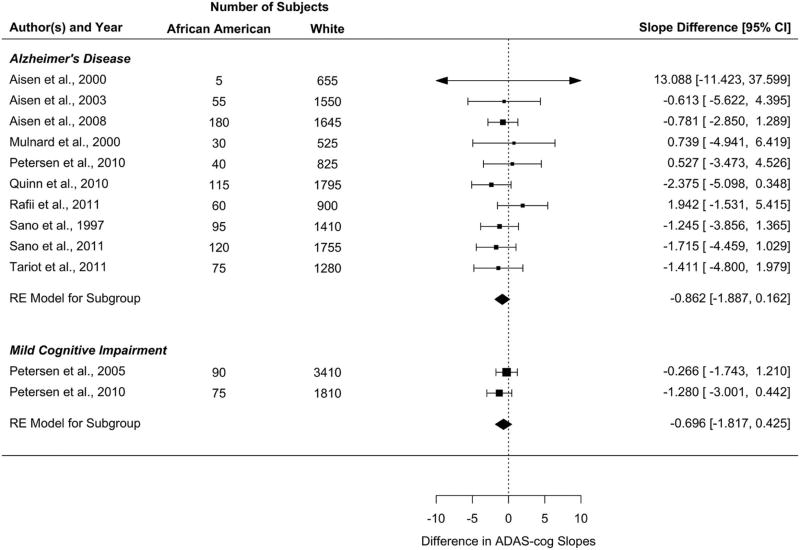

Meta-analysis of rate of progression for AD and MCI for 11 studies is shown in Figure 3. African Americans with AD showed a rate of progression on the ADAS-cog that was not significantly different from whites with AD (estimated difference= −0.862 points/year, Wald 95% CI [−1.887, 0.162]). Similarly, African Americans with MCI did not have a significantly different rate of progression on the ADAS-cog compared to whites with MCI (estimated difference= −0.696 points/year, Wald 95% CI [−1.817, 0.425]). The Cochran’s Q test of heterogeneity was not significant (Q=6.276, df=9, p=0.712 for AD and Q=0.767, df=1, p=0.381 for MCI). Funnel plots showed no significant evidence of publication bias (Supplemental Figures 1b and 1c).

Figure 3. Forest plot of differences in the rate of progression on the ADAS-cog in African Americans compared to whites.

Estimates are presented for both AD and MCI. Estimates for individual studies are differences in slope (rate of progression) in African Americans and whites and the associated Wald-type 95% confidence interval (CI). Estimates were combined using a random-effects (RE) meta-analytic model with restricted maximum likelihood (REML).

Simulations

Power to detect the simulated treatment effect in a mixed model analysis is shown across a range of sample sizes and effect sizes for AD (Supplemental Figure 2) and MCI (Supplemental Figure 3). As the percentage of African American subjects increased from 20% to 80%, there was little effect on overall power, which was primarily driven by sample size and effect size. For smaller sample sizes of 100 per group of less, there were slight (less than 5%) differences in power across the range of African American participation. This difference decreased with larger sample sizes, so that power remained practically equal for samples of 200 or more per group. Similar results were seen for subjects with MCI, with a difference in power of up to 12% across the range of African American participation when sample size was 100 per group or less. This difference again was minimal for sample sizes of 200 or more per group.

DISCUSSION

This study represents the most comprehensive examination of African American participation in AD clinical trials to date, and the first to investigate potential effects of increasing the percentage of African American enrollment. Across 17 different clinical trials and observational studies spanning a range of AD severity, we found that African Americans had lower rates than whites for many comorbid medical disorders at study entry. Cardiovascular disorders were a notable exception. The higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease among African Americans is consistent with the prevalence in this subgroup in the general population.(29, 30) African Americans were at lower risk of diseases affecting other organ systems, which runs counter to the increased risk of disease commonly observed for many forms of cancer, diabetes, stroke, and other disorders.(31) However, individuals selected for clinical trials in AD are not necessarily representative of the population with AD,(5) and these results suggest that African Americans enrolled in AD clinical trials represent a select subgroup that is healthier than the general population.

African American subjects had 60% greater odds of dropping out of the study (or missing the final study visit) compared to whites. Greater attrition among minorities has been reported in previous observational studies of AD,(32, 33) but our study is the first to extend these racial differences to AD clinical trials. Increased dropout rate among African Americans may be due in part to demographic differences, as lower education and lack of spousal involvement observed in our analysis, which are associated with dropout in observational studies.(32–34)

Whether racial differences on the ADAS-cog occur is the most critical question for AD clinical trials, as this would affect power to detect treatment effects. In both AD and MCI, we observed statistically nonsignificant differences for rate of progression on the ADAS-cog, demonstrating that increased African American enrollment is not likely to affect statistical power for trials. We confirmed these findings using clinical trial simulations. There was a small decrease in power to detect treatment effects with increasing percentages of African Americans when sample size was less than 100 subjects per treatment group. However, within sample sizes typically used in phase III clinical trials for AD (200 or more subjects per treatment group), the effect of race on power was minimal. Collectively, these results provide empirical evidence for recommendations by experts to increase enrollment of minorities in AD clinical trials, particularly given the higher rates of AD in African Americans.(1, 5, 35) However, our results specifically indicate that increased enrollment of African Americans similar to current enrollees, who differ from the general population in overall health, is unlikely to affect trial efficiency. Enrollment of more representative African American subjects in AD clinical trials is encouraged, but should be monitored for its effect on trial outcomes.

Results of this analysis should not be taken as an indication that increasing minority enrollment in AD clinical trials is unnecessary because outcomes among minority and nonminority subjects are similar. Indeed, this investigation highlights several reasons why increasing minority participation is critical. African Americans were more likely to have comorbid cardiovascular disorders than whites, which may necessitate adjustment in medication dosages or may predispose them to certain adverse events that can best be detected in the clinical trial setting. The increased dropout rate among African Americans warrants special attention to methods to promote medication compliance and attendance in this subgroup, particularly if dropouts are due to other demographic factors (such as lower education or lack of spousal participation) that may require specific recruitment and retention strategies.(33, 36)

Our study has several notable strengths, including use of a large number of clinical trials and observational studies for meta-analysis to increase the number of African American subjects, and use of clinical trial simulations to confirm results of the meta-analysis. However, there are limitations that must be considered in interpreting our results. Despite combining multiple studies in meta-analysis, the number of African American subjects still remains small at 7% of AD participants, 4% of MCI participants, and 11% of normal participants. Results for less common disorders would be particularly susceptible to influence by outliers and must be interpreted with some caution, pending confirmation in other studies. As already noted, African Americans enrolled in clinical trials may not be representative of the overall population of African Americans with AD.(5) We also restricted our analyses to African Americans, who were the largest minority subgroup, rather than combine multiple racial groups. As other minorities are similarly underrepresented in AD clinical trials, future research should examine the consequences of increasing enrollment among these groups. The small number of studies available for MCI also makes generalization in this population more difficult, although the two trials analyzed did have a large number of subjects. Another limitation is that only one cognitive outcome, the ADAS-cog, was examined. Although this is still the most common outcome for AD clinical trials, use of other outcome measures such as the CDR(37) may yield different results. Finally, although results of simulations are valuable in guiding trial design and subject selection, they may not adequately model complexities of AD and do require confirmation in real-world trials.

Overall, this study provides firm support for recommendations of increasing African American enrollment in AD clinical trials but highlights several key issues that must be addressed when recruiting diverse populations. Inclusion of more diverse samples in future studies of treatments for AD will allow us to better address the needs of all individuals who are experiencing the consequences of this devastating disorder.

Supplementary Material

Table 1. Characteristics of Subjects across all Studies at Baseline.

Subjects are classified as Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or normal (NL) at the time of study entry. HS=high school.

| AD | MCI | NL | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | African American (N=232) |

White (N=3304) |

P Value | N | African American (N=50) |

White (N=1147) |

P Value | N | African American (N=94) |

White (N=729) |

P Value | |

| Age, years | 3525 | 74.75+/− 8.49 | 75.40+/− 8.43 | F1,3523=1.45 p=0.228 | 1197 | 73.42+/− 8.25 | 73.92+/− 7.23 | F1,1195=0 p=0.953 | 823 | 76.21+/− 5.91 | 76.62+/− 6.26 | F1,821=0.3 p=0.587 |

| Education, less than HS | 3536 | 34% (78) | 14% (454) | p<0.001 | 1197 | 22% (11) | 8% (88) | p<0.001 | 823 | 18% (17) | 4% (32) | p<0.001 |

| HS graduate | 47% (109) | 51% (1680) | 40% (20) | 39% (452) | 48% (45) | 37% (273) | ||||||

| College graduate | 19% (45) | 35% (1170) | 38% (19) | 53% (607) | 34% (32) | 58% (424) | ||||||

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 3536 | 1% (3) | 2% (73) | p=0.648 | 1197 | 0% (0) | 1% (8) | p=0.768 | 823 | 0% (0) | 0% (1) | 0.772 |

| Not Hispanic | 98% (228) | 97% (3216) | 100% (50) | 99% (1135) | 100% (94) | 99% (725) | ||||||

| Unknown | 0% (1) | 0% (15) | 0% (0) | 0% (4) | 0% (0) | 0% (3) | ||||||

| Marital Status, Married | 3536 | 45% (105) | 71% (2353) | p<0.001 | 1196 | 42% (21) | 78% (894) | p<0.001 | 823 | 32% (30) | 63% (456) | p<0.001 |

| Widowed | 41% (94) | 23% (751) | 30% (15) | 14% (161) | 45% (42) | 23% (169) | ||||||

| Divorced | 12% (28) | 4% (128) | 22% (11) | 6% (65) | 16% (15) | 9% (66) | ||||||

| Never married | 2% (5) | 2% (67) | 6% (3) | 2% (26) | 5% (5) | 5% (37) | ||||||

| Unknown | 0% (0) | 0% (5) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 2% (2) | 0% (1) | ||||||

| Sex, female | 3536 | 71% (165) | 58% (1902) | p<0.001 | 1197 | 62% (31) | 42% (481) | p=0.005 | 823 | 77% (72) | 56% (411) | p<0.001 |

| placebo Treatment in Original Study, placebo | 3361 | 44% (93) | 48% (1521) | p=0.263 | 1167 | 77% (37) | 61% (677) | p=0.021 | 811 | 100% (93) | 100% (718) | --- |

| Number of Organ Systems Affected | 3536 | 5.09+/− 3.15 | 5.77+/− 3.00 | F1,3534=16.5 p<0.001 | 1197 | 5.66+/− 2.96 | 5.86+/− 2.67 | F1,1195=0.61 p=0.436 | 823 | 5.56+/− 2.72 | 6.24+/− 2.61 | F1,821=5.33 p=0.021 |

| ADAS-cog, baseline | 2578 | 26.4+/− 11.7 | 25.8+/− 10.9 | F1,2576=0.63 p=0.428 | 943 | 10.10+/− 3.59 | 11.36+/− 4.39 | F1,941=1.33 p=0.249 | 245 | 6.89+/− 3.40 | 5.91+/− 2.85 | F1,243=1.33 p=0.25 |

| Month 6 | 2145 | 27.6+/− 11.8 | 27.0+/− 11.6 | F1,2143=0.55 p=0.459 | 817 | 9.19+/− 3.79 | 11.30+/− 5.34 | F1,815=3.07 p=0.08 | 148 | 6.81+/− 3.46 | 5.88+/− 2.80 | F1,146=0.61 p=0.436 |

| Month 12 | 1851 | 28.1+/− 12.5 | 28.7+/− 12.4 | F1,1849=0 p=0.963 | 763 | 9.43+/− 4.55 | 11.91+/− 5.99 | F1,761=3.02 p=0.083 | 141 | 5.76+/− 2.95 | 5.68+/− 2.87 | F1,139=0.01 p=0.928 |

| Month 18 | 1150 | 29.2+/− 13.5 | 30.6+/− 13.2 | F1,1148=0.51 p=0.475 | 683 | 9.17+/− 3.21 | 12.63+/− 6.82 | F1,681=4.37 p=0.037 | ---* | ---* | ---* | ---* |

| Month 24 | 278 | 38.9+/− 11.8 | 36.1+/− 14.1 | F1,276=0.76 p=0.383 | 642 | 10.87+/− 4.74 | 12.99+/− 7.16 | F1,640=1.21 p=0.271 | 134 | 8.20+/− 5.26 | 5.67+/− 3.03 | F1,132=0.95 p=0.331 |

Statistical tests are shown with the degrees of freedom in subscripts.

Studies did not collect information on this subgroup at this time point.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this report was provided by NIH R01 AG037561 (REK, GRC, GW, LSS), NIH P50 AG05142, ADRC (LSS), and NIH P30 AG031054 (K. Burgio, PI; REK was PI of a Pilot Grant). The funding agency has no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Data used in the preparation of this study were obtained from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI, NIA U01 AG024904) database (www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (NIH AG10483).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Previous Presentation: Data from this manuscript previously appeared as part of an oral presentation at the 7th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease meeting, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 20–22, 2014.

No disclosures to report.

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no relationships with any commercial entity that would affect the results of the study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Richard E. Kennedy contributed to the obtaining of funding, the study concept and design, the analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, and drafting/revising the manuscript for content.

Dr. Gary R. Cutter contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting/revising the manuscript for content.

Dr. Guoqiao Wang contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting/revising the manuscript for content.

Dr. Lon S. Schneider contributed to obtaining of funding, the study concept and design, and drafting/revising the manuscript for content.

References

- 1.Olin JT, Dagerman KS, Fox LS, et al. Increasing ethnic minority participation in Alzheimer disease research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16(Suppl 2):S82–85. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200002-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansell DA, McDonald EK. Bias, black lives, and academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1087–1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nowrangi MA, Rao V, Lyketsos CG. Epidemiology, assessment, and treatment of dementia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34:275–294. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider LS, Olin JT, Lyness SA, et al. Eligibility of Alzheimer's disease clinic patients for clinical trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:923–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider LS. Drug development, clinical trials, cultural heterogeneity in Alzheimer disease: the need for pro-active recruitment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19:279–283. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000190808.97878.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitfield KE. Challenges in cognitive assessment of African Americans in research on Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16(Suppl 2):S80–81. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200002-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dilworth-Anderson P, Hendrie HC, Manly JJ, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of Alzheimer's disease in diverse populations. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy RE, Cutter GR, Schneider LS. Effect of APOE genotype status on targeted clinical trials outcomes and efficiency in dementia and mild cognitive impairment resulting from Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thal L. Development of the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Int J Geriatr Psychopharmacol. 1997;1:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74:201–209. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohs RC, Knopman D, Petersen RC, et al. Development of cognitive instruments for use in clinical trials of antidementia drugs: additions to the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale that broaden its scope. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11:S13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:486–504. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown H, Prescott R. Applied Mixed Models in Medicine. 2. Chichester: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddiqui O, Hung HMJ, O'Neill R. MMRM vs. LOCF: a comprehensive comparison based on simulation study and 25 NDA datasets. J Biopharm Stat. 2009;19:227–246. doi: 10.1080/10543400802609797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burton A, Altman DG, Royston P, et al. The design of simulation studies in medical statistics. Stat Med. 2006;25:4279–4292. doi: 10.1002/sim.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider LS, Kennedy RE, Cutter GR, et al. Requiring an amyloid-β1–42 biomarker for prodromal Alzheimer's disease or mild cognitive impairment does not lead to more efficient clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2379–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doody RS, Ferris SH, Salloway S, et al. Donepezil treatment of patients with MCI: a 48-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2009;72:1555–1561. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000344650.95823.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider LS, Kennedy RE, Cutter GR. Estimating power with effect size versus slop differences: Both means and variance matter. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:247–249. [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian L, Cai T, Pfeffer MA, et al. Exact and efficient inference procedure for meta-analysis and its application to the analysis of independent 2 × 2 tables with all available data but without artificial continuity correction. Biostatistics. 2009;10:275–281. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viechtbauer W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watkins LO. Epidemiology and burden of cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27:III2–6. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960271503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duthie A, Chew D, Soiza RL. Non-psychiatric comorbidity associated with Alzheimer's disease. QJM. 2011;104:913–920. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manton KG, Stallard E. Health and disability differences among racial and ethnic groups. In: Martin LG, Soldo BJ, editors. Racial and ethnic differences in the health of older Americans. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. pp. 43–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koss E, Peterson B, Fillenbaum GG. Determinants of attrition in a natural history study of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13:209–215. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199910000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinton L, Carter K, Reed BR, et al. Recruitment of a community-based cohort for research on diversity and risk of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:234–241. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181c1ee01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coley N, Gardette V, Toulza O, et al. Predictive factors of attrition in a cohort of Alzheimer disease patients. The REAL.FR study. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:69–79. doi: 10.1159/000144087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shadlen M-F, McCormick WC, Larson EB. Research agenda for understanding Alzheimer disease in diverse populations: work group on cultural diversity, Alzheimer's association. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16(Suppl 2):S96–S100. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200002-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero HR, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Gwyther LP, et al. Community engagement in diverse populations for Alzheimer disease prevention trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:269–274. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.