Abstract

Objective

To examine labor induction by race/ethnicity and factors associated with disparity in induction.

Study Design

This is a retrospective cohort study of 143,634 women eligible for induction ≥24 weeks’ gestation from 12 clinical centers (2002–2008). Rates of labor induction for each racial/ethnic group were calculated and stratified by gestational age intervals: early preterm (240/7–336/7), late preterm (340/7–366/7), and term (370/7–416/7 weeks). Multivariable logistic regression examined the association between maternal race/ethnicity and induction controlling for maternal characteristics and pregnancy complications. The primary outcome was rate of induction by race/ethnicity. Inductions that were indicated, non-medically indicated, or without recorded indication were also compared.

Results

Non-Hispanic black (NHB) women had the highest percentage rate of induction, 44.6% (p < 0.001). After adjustment, all racial/ethnic groups had lower odds of induction compared with non-Hispanic white (NHW) women. At term, NHW women had the highest percentage rate (45.4%) of non-medically indicated or induction with no indication (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Compared with other racial/ethnic groups, NHW women were more likely to undergo non-medically indicated induction at term. As labor induction may avoid the occurrence of stillbirth, whether this finding explains part of the increased risk of stillbirth for NHB women at term merits further research.

Keywords: disparity, labor, induction, obstetrics, race, ethnicity

Racial and ethnic disparities in obstetrical outcomes have been described in the United States. Non-Hispanic black (NHB) women have a higher risk for preterm birth, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, cesarean delivery, and stillbirth compared with non-Hispanic white (NHW) women.1–4 Conversely, NHB women are less likely to receive early prenatal care, be hospitalized for gestational hypertension, or have a successful vaginal birth after cesarean section.4–6 Hispanic women, who are often of the same socioeconomic status, on average have notably better birth outcomes than NHB women.7

Given higher rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality among black women in the United States,8,9 higher odds of induction might be expected when compared with white women. However, previous studies have found that NHB women are induced significantly less often than NHW women, and this disparity appears to be increasing with time.10–12 A disparity in the rate of induction may contribute to the racial differences in stillbirth rates observed at term.4 Previous studies examining differences in labor induction by race have been limited by the use of birth certificate data and have also been unable to investigate the indications for induction.10–13 Thus, we chose to examine induction of labor by race/ethnicity and the factors that contribute to any differences using electronic medical record (EMR) data from a large, contemporary United States cohort study, the Consortium on Safe Labor (CSL).

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study after receiving approval by the institutional review board of the MedStar Health Research Institute. We used data from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development supported Consortium on Safe Labor, which was a multicenter, retrospective cohort study that collected detailed labor and delivery information in electronic medical records (EMRs) on 228,562 pregnancies from 12 clinical centers (with 19 hospitals) across nine American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists U.S. districts from 2002 to 2008. By design, study hospitals had obstetric EMRs from which data were abstracted and mapped to pre-specified fields. Maternal International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes were also collected for each delivery. Investigators at each site completed surveys on hospital and physician characteristics. Data inquiries, cleaning, and logic checking were performed. Validation studies for four key outcome diagnoses (cesarean for non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing, asphyxia, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission for respiratory conditions, and shoulder dystocia) confirmed a high level of accuracy: >95% concordance with the medical chart for 16/20 variables examined with the lowest concordance of 91.1% for a clinical diagnosis of shoulder dystocia.14

The primary outcome of interest was induction of labor at 24 weeks of gestation or greater. After the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, there were 143,634 women identified as eligible for analysis (Fig. 1). Race/ethnicity was defined as had been recorded in the EMR and was categorized as NHW, NHB, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander. Pregnancies in which more than one race/ethnicity or “Other” was recorded were combined as Other/Multi-racial.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for study selection. Deliveries at or >42 weeks of gestation were excluded (n = 1,154) from analyses in Tables 3 and 4, leaving n = 142, 480 for these analyses. CD, cesarean delivery; GA, gestational age.

Induction of labor was identified if an induction and/or a method or start time for induction was recorded in the EMR. We defined three categories for induction of labor: “indicated,” “non-medically indicated,” and “no recorded indication” using the following algorithm. The indication for induction was used first to classify the induction into one of the three categories. Since the indication for induction was not always provided, we supplemented the indication for induction with all potential maternal, fetal, or obstetric complications of pregnancy as previously described.15 For example, if a woman had an induction of labor, and no indication was recorded, but the pregnancy was complicated by gestational diabetes, she was included in the indicated category. We also included women who were admitted to labor and delivery for an “unspecified fetal or maternal reason” in the indicated category. If a site indicated that the induction was elective, no other indications for induction were provided, and there were no other obstetric, fetal, or maternal conditions complicating the pregnancy, the induction was designated as non-medically indicated. If a delivery indication was noted as postdates or post-term, and no other indications were listed, but the induction occurred prior to 41 weeks of gestation, these were also coded as non-medically indicated. Finally, those inductions where no indication for the induction was provided, and where no obstetric, fetal, or maternal conditions of the pregnancy could be identified were classified as no recorded indication.

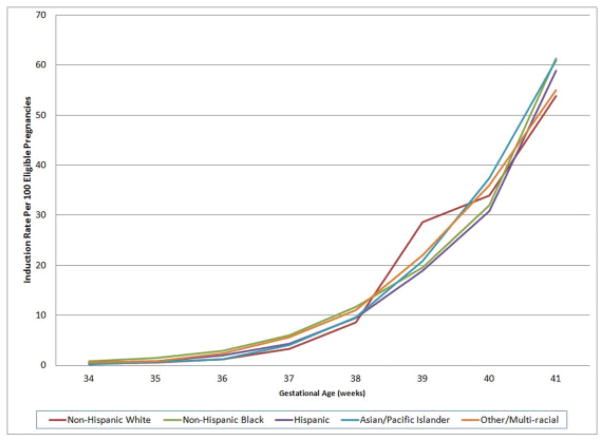

The percentage of eligible women undergoing labor induction was calculated by race/ethnicity overall and then for each completed week of gestation. The percentage of women undergoing induction in a given week was calculated by dividing the number of inductions that occurred in a given week by the number of eligible pregnancies that were undelivered at the same gestational week. The percentage was expressed as the number of inductions per 100 eligible pregnancies and was calculated separately for each racial/ethnic group. The percentages were plotted graphically for each week of gestation.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the association between race/ethnicity and induction while adjusting for the following confounders: maternal age, marital status, maternal insurance type, parity, admission body mass index (BMI), tobacco use, maternal hypertensive disorders (which included gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, superimposed preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, and unspecified hypertensive disorders), pregestational diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes mellitus, maternal renal disease, fetal anomaly, stillbirth, fetal condition (including intrauterine growth restriction, abnormal antenatal fetal testing, Rhincompatibility, oligohydramnios, and fetal compromise), premature rupture of membranes (PROM), antepartum chorioamnionitis, delivery institution type (university, teaching community, or non-teaching community hospital), and site. BMI was analyzed as a categorical variable: underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5 ≤ 25 kg/m2), overweight (25 ≤ 30 kg/m2), and obese (≥30 kg/m2). Deliveries at or >42 weeks of gestation were excluded (n = 1,154) leaving n = 142, 480 for the analysis (Fig. 1). Multiple imputation technique16 for missing values of maternal age (n = 40), BMI at admission (n = 23,820), and marital status (n = 3,499) was performed based on fully conditional specification.17 The missing data were filled in 10 times to generate 10 complete datasets. Each dataset was analyzed with multivariate logistic regression models. The results from these complete datasets were then combined for the inferences.18 Models were created to examine the odds of induction for all deliveries occurring at 24 weeks or greater, and separately for the three gestational age intervals: “early preterm” (240/7–336/7 weeks of gestation), “late preterm” (340/7–366/7 weeks’), and “term” (370/7–416/7 weeks’). Gestational age was adjusted for in the overall model as a categorical variable (early preterm, late preterm, and term).The unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of induction and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using NHWs as the referent group.

To examine the factors associated with racial/ethnic differences in labor induction, we compared the percentage of inductions for each race/ethnicity that were indicated, non-medically indicated, or no recorded indication overall and then performed stratified analysis by the three gestational age intervals of early preterm, late preterm, and term.

Comparisons were made using Pearson’s Chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, and analysis of variance (ANOVA). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Induction of labor occurred in 42.7% of the 143,634 pregnancies identified as eligible for induction. NHB women had the greatest percentage to undergo induction of labor (44.6%), followed by Other/Multi-racial (44.0%), NHWs (42.3%), Hispanics (42.2%), and Asian/Pacific Islanders (38.6%, p < 0.001).

Of the 9,582 women initially excluded due to missing or unknown racial data, 6,860 women would have been identified as eligible for induction after applying the same exclusions. In this cohort, 36.6% of the pregnancies were induced. This percentage was significantly lower than encountered in the cohort of interest, where race was identified (42.7%, p < 0.001).

The demographic characteristics of the 143,634 pregnancies eligible for induction are listed in Table 1. Of all the groups, NHW women most often had private insurance and delivered at a teaching-community or non-teaching community hospital. NHBs were more often single, cigarette smokers, had a higher BMI at labor admission, and had a public funding source for their care. Asian/Pacific Islanders were more often older, married, and nulliparous.

Table 1.

Demographics of women eligiblea for induction of labor

| Non-Hispanic white (n = 75,097, 52.3%) | Non-Hispanic black (n = 31,663, 22.0%) | Hispanic (n = 26,524, 18.5%) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 6,503, 4.5%) | Other/Multi-racial (n = 3,847, 2.7%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean, years | 28.2 | 25.4 | 26.4 | 29.7 | 27.5 | <0.001 |

| BMI at admission, mean, kg/m2 | 29.9 | 32.4 | 30.8 | 28.1 | 30.6 | <0.001 |

| Marital status, % | ||||||

| Married | 79.9 | 23.1 | 48.6 | 84.3 | 58.6 | <0.001 |

| Divorced/widowed | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.6 | |

| Single | 18.3 | 75.8 | 49.8 | 15.0 | 39.8 | |

| Nulliparous, % | 46.2 | 45.9 | 44.5 | 56.7 | 49.2 | <0.001 |

| Funding source, % | ||||||

| Private | 75.3 | 34.0 | 29.7 | 69.2 | 34.6 | <0.001 |

| Public | 17.4 | 49.8 | 42.7 | 13.4 | 34.5 | |

| Self-pay | 0.7 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.5 | |

| Other/unknown | 6.6 | 14.4 | 26.0 | 15.2 | 28.3 | |

| Delivery institution, % | ||||||

| University-affiliated hospital | 24.4 | 65.8 | 61.3 | 41.4 | 67.9 | <0.001 |

| Teaching community hospital | 60.3 | 34.1 | 35.9 | 53.7 | 31.6 | |

| Non-teaching community hospital | 15.3 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 4.9 | 0.6 | |

| Smoker, % | 6.4 | 7.5 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 5.6 | <0.001 |

| Induced, % | 42.3 | 44.6 | 42.2 | 38.6 | 44.0 | <0.001 |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Eligible pregnancies included singleton pregnancies with vertex presentation delivering at 24 weeks of gestation or greater in women not undergoing a prelabor cesarean, without placenta previa, and labor onset was known (n = 143,634).

With regard to maternal and fetal complications of pregnancy (Table 2), NHB women were more likely to have pregnancies affected by hypertensive disorders, pre-existing diabetes mellitus, stillbirth, and other fetal conditions compared with all groups. Asian/Pacific Islanders were more likely to have gestational diabetes, fetal anomalies, PROM, and chorioamnionitis compared with other races/ethnicities.

Table 2.

Antepartum complications of women eligible for induction

| Non-Hispanic White (n = 75,097) | Non-Hispanic Black (n = 31,663) | Hispanic (n = 26,524) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 6,503) | Other/Multi-racial (n = 3,847) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertensive disorder,a % | 9.0 | 15.7 | 9.7 | 6.6 | 11.2 | <0.001 |

| Preexisting diabetes, % | 1.1 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes, % | 3.9 | 4.0 | 5.9 | 9.2 | 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Maternal renal disease, % | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Fetal anomaly, % | 5.4 | 7.9 | 6.7 | 9.3 | 6.3 | <0.001 |

| Antepartum fetal death (stillbirth), % | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Fetal condition,b % | 7.9 | 15.8 | 9.9 | 11.8 | 11.5 | <0.001 |

| PROM, % | 15.0 | 12.8 | 12.3 | 17.3 | 11.2 | <0.001 |

| Chorioamnionitis, % | 2.0 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 3.5 | <0.001 |

Abbreviation: PROM, premature rupture of membranes.

Maternal hypertensive disorder included gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, superimposed preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, and unspecified hypertensive disorders.

Fetal condition included intrauterine growth restriction, abnormal antenatal fetal testing, Rh incompatibility, oligohydramnios, and fetal compromise.

Fig. 2 graphically depicts the rate of induction for each week by racial/ethnic group at or after 34 weeks. Prior to 39 weeks, minor differences were observed between the racial/ethnic groups, with NHB women having the highest rate of induction. At 39 weeks, however, a dramatic increase in the rate of induction for NHWs was observed above all other racial/ethnic groups when they previously had the lowest rate.

Fig. 2.

Weekly rate of labor induction by race/ethnicity from 34 to 41 weeks of gestation.

The examination of the odds of labor induction by maternal race/ethnicity and gestational age intervals is depicted in Table 3. Overall, we observed unadjusted odds of labor induction that were 9% and 5% higher for NHB and Other/Multi-racial women, respectively, compared with NHW women and were 2% and 15% lower for Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islanders, respectively. However, after adjustment for maternal characteristics and pregnancy complications, the overall odds of labor induction for all race/ethnicities was less than that for NHW women. When stratified by gestational age at delivery and adjusted for maternal characteristics and pregnancy complications, no differences of significance were seen in early preterm (<34 weeks of gestation). During the late preterm period, significant differences were observed only for Asian/Pacific Islanders (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53–0.90) in comparison to NHWs. At 37 to <42 weeks’, the odds of labor induction for all race/ethnicities were 25 to 40% less when compared with that for NHWs.

Table 3.

Odds of labor induction by maternal race/ethnicity and gestational age at delivery

| Number of deliveries during interval (% of deliveries during interval) | Induction of labor unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Induction of labor adjusteda OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (24 to <42 weeks) | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 74,658 (52.4) |

Referent | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic black | 31,384 (22.0) |

1.09 (1.06–1.12) |

0.69 (0.66–0.71) |

| Hispanic | 26,173 (18.4) |

0.98 (0.95–1.01) |

0.63 (0.61–0.65) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6,479 (4.6) |

0.85 (0.81–0.90) |

0.75 (0.71–0.79) |

| Other/multi-racial | 3,786 (2.7) |

1.05 (0.99–1.13) |

0.65 (0.60–0.70) |

| Early preterm (24 to <34 weeks) | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,292 (34.0) |

Referent | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1,529 (40.3) |

1.62 (1.37–1.90) |

0.96 (0.77–1.21) |

| Hispanic | 715 (18.8) |

1.38 (1.13–1.69) |

0.98 (0.75–1.27) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 96 (2.5) |

1.50 (0.96–2.34) |

1.41 (0.83–2.40) |

| Other/multi-racial | 166 (4.4) |

1.45 (1.02–2.05) |

0.82 (0.53–1.28) |

| Late preterm (34 to < 37 weeks) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4,660 (45.6) |

Referent | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic black | 3,024 (29.6) |

1.97 (1.80–2.17) |

0.91 (0.79–1.05) |

| Hispanic | 1,891 (18.5) |

1.64 (1.47–1.83) |

0.94 (0.81–1.10) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 374 (3.7) |

1.09 (0.88–1.36) |

0.69 (0.53–0.90) |

| Other/multi-racial | 266 (2.6) |

1.77 (1.38–2.26) |

0.76 (0.56–1.04) |

| Term (37 to < 42 weeks) | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 68,706 (53.5) |

Referent | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic black | 26,831 (20.9) |

1.05 (1.02–1.08) |

0.66 (0.63–0.68) |

| Hispanic | 23,567 (18.3) |

0.95 (0.92–0.98) |

0.60 (0.58–0.63) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6,009 (4.7) |

0.83 (0.79–0.88) |

0.75 (0.70–0.79) |

| Other/multi-racial | 3,354 (2.6) |

1.03 (0.96–1.10) |

0.64 (0.59–0.69) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Deliveries at or greater than 42 weeks of gestation were excluded (n = 1,154) leaving n = 142, 480 for this analysis.

Adjusted for maternal age, marital status, maternal insurance type, delivery institution type, parity, admission body mass index, smoking, maternal hypertensive disorders (which included gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, superimposed preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, and unspecified hypertensive disorders), pregestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, maternal renal disease, fetal anomaly, stillbirth, fetal condition (including intrauterine growth restriction, abnormal antenatal fetal testing, Rh incompatibility, oligohydramnios, and fetal compromise), premature rupture of membranes (PROM), antepartum chorioamnionitis, and site.

Analyses of the indications for induction are presented by maternal race/ethnicity in Table 4. Overall, NHBs had the highest percentage of indicated inductions of labor compared with all other racial/ethnic groups. Conversely, NHWs had the highest percentage of non-medically indicated inductions. Among NHW women, 45.4% of all inductions were non-medically indicated or had no recorded indication, and this was significantly higher than any other racial/ethnic group (NHB 29.4%, Hispanic 37.0%, Asian/Pacific Islander 31.3%, and Other/Multi-racial 36.4%, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Indications for induction stratified by maternal race/ethnicity and gestational age at delivery

| Non-Hispanic white | Non-Hispanic black | Hispanic | Asian/Pacific Islander | Other/Multi-racial | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (24 to <42 weeks) | ||||||

| n | 31,566 | 13,932 | 10,949 | 2,492 | 1,649 | – |

| Indicated,a % | 54.6 | 70.6 | 63.0 | 68.7 | 63.6 | <0.001 |

| Non-medically indicated,b % | 31.8 | 8.1 | 9.6 | 11.8 | 4.3 | <0.001 |

| No recorded indication,c % | 13.6 | 21.3 | 27.4 | 19.5 | 32.1 | <0.001 |

| Early preterm (24 to <34 weeks) | ||||||

| n | 323 | 535 | 225 | 32 | 54 | – |

| Indicated, % | 92.9 | 89.2 | 88.4 | 96.9 | 92.6 | 0.19 |

| Non-medically indicated, % | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.54 |

| No recorded indication, % | 6.8 | 10.8 | 11.6 | 3.1 | 7.4 | 0.16 |

| Late preterm (34 to <37 weeks) | ||||||

| n | 1,527 | 1,483 | 841 | 130 | 123 | – |

| Indicated, % | 88.7 | 85.0 | 80.3 | 88.5 | 82.1 | <0.001 |

| Non-medically indicated, % | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.007 |

| No recorded indication, % | 9.7 | 14.6 | 19.1 | 10.8 | 17.9 | <0.001 |

| Term (37 to <42 weeks) | ||||||

| n | 29,716 | 11,914 | 9,883 | 2,330 | 1,472 | – |

| Indicated, % | 52.5 | 67.9 | 61.0 | 67.2 | 61.0 | <0.001 |

| Non-medically indicated, % | 33.7 | 9.4 | 10.6 | 12.6 | 4.8 | <0.001 |

| No recorded indication, % | 13.9 | 22.6 | 28.4 | 20.3 | 34.2 | <0.001 |

Deliveries at or >42 weeks of gestation were excluded (n = 1,154) leaving n = 142, 480 for this analysis.

Indicated includes inductions with an indication provided and pregnancies affected by a potential maternal, fetal, or obstetric complications of pregnancy.

Non-medically indicated includes inductions identified as ‘elective’ and there were no other obstetric, fetal, or maternal conditions complicating the pregnancy.

No recorded indication includes all inductions where no obstetric, fetal or maternal conditions of the pregnancy could be identified, and those where no indication for the induction was provided.

Upon stratification by gestational age interval, no significant differences in the indications for induction were observed between the racial/ethnic groups prior to 34 weeks of gestation (Table 4). During late preterm, the percentage of NHW women to undergo a non-medically indicated induction was higher (1.6%) than any other racial/ethnic group (p = 0.007). At term, NHB women most often underwent an indicated induction. Conversely, 47.6% of inductions amongst NHWs at term were either non-medically indicated or for no recorded indication.

Discussion

In a large U.S. obstetrical cohort, there were racial/ethnic differences in labor induction. NHB women were induced more often than any other racial/ethnic group, and the primary reason was for an antepartum complication, such as diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, preeclampsia, or fetal growth restriction. However, after adjusting for maternal characteristics and antepartum complications, we found that NHW women had the highest odds of labor induction overall and at term (370/7–416/7 weeks) compared with other racial/ethnic groups. This can best be explained by the finding that 47.6% of inductions in NHW women at term were non-medically indicated or with no recorded indication.

Racial/ethnic differences in rates of induction are important to study because it has been suggested that these differences could explain the racial disparities in stillbirth at term. The overall stillbirth rate for NHB women is 2.3 times that of NHW women. Much of this black–white disparity in stillbirth remains unexplained.19 At term gestation, NHB women have a 1.6 times higher risk of stillbirth compared with NHW women according to NCHS Perinatal Mortality Data (2001–2002).3 In the CSL cohort, the risk of antepartum stillbirth was 2.25 times greater for NHB women compared with that for NHW women during the term period.20 NHB women may have a higher risk of stillbirth due to the lower rates of induction at term compared with NHW women.4 Indeed, we found that despite higher rates of preexisting medical diseases and complications of pregnancy, NHB women had lower odds of induction at late preterm and at term after taking these factors into account.

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) data reported that 24.0% of births to whites were induced compared with 20.7% of black women.1 The literature examining differences in induction by race/ethnicity by indication is limited. Murthy et al examined differences in induction by race/ethnicity using Illinois birth certificate data and found that African-American women undergo labor induction less frequently.10 Using birth certificate data from the NCHS from 1991 to 2006, Murthy et al also showed that early term induction rates (37 and 38 weeks of gestation) were highest for NHW women and remained higher even after adjusting for confounding demographic and medical risk factors when compared with that of Hispanic and black women.12 However, in another study from this same group, induction rates were higher for black women in the late preterm period (340/7–366/7 weeks) compared with other race/ethnicities.11 While the findings of our study are similar, there are some differences. In particular, we did not find increased odds of induction during the late preterm period for NHBs compared with NHWs. These differences might be due to differences in the populations, as Murthy et al excluded women with PROM, pregnancy-associated hypertension, and fetal anomalies when there are known racial differences in the prevalence of these conditions.7 In addition, since they were unable to control for socioeconomic factors or the type of institution where the delivery occurred, they were unable to account for variable obstetrical practice patterns that may occur at different types of institutions (e.g., teaching versus non-teaching hospital). Our study used data from medical records which, unlike birth certificate data, allowed us to control for some of these important socioeconomic factors. It is unknown what caused racial/ethnic differences in labor inductions. It may have been due to differences within or between institutions, variations across providers, patient choice, or combinations thereof.

The novel aspect of our study was the ability to explore the racial disparities in the indications for induction in a large recent cohort with electronic medical record data. While the ideal timing of delivery for many pregnancy complications has not been established,21 we found significant racial differences in current clinical practice. Our study was limited because the indication for induction was not always provided. We cannot rule out that there was misclassification in assignment of women to indication group. We chose to supplement the indicated induction group by using any other maternal or fetal condition recorded that could have resulted in an induction even though it may not have been the actual indication for induction. In addition, there were also inductions with no identifiable indication despite our conservative efforts to include any possible condition. Of the pregnancies with no identifiable indication for induction, 94.0% delivered at 37 weeks of gestation or later and 5.1% at late preterm, and only 0.8% delivered prior to 34 weeks of gestation. We suspect that a majority of the inductions with no recorded indication after 34 weeks were non-medically indicated given that they most often occurred at term, and the large number of variables considered in the CSL to capture pregnancy complications. In other studies examining CSL patient data, women with no recorded indication for induction had similar labor patterns and low cesarean delivery rates, as women with non-medically indicated deliveries further indicating that these were likely non-medically indicated.20 While it is unlikely that the inductions with no recorded indication that occurred early preterm were non-medically indicated, it is reassuring that these numbers were reasonably small. Our findings might only be applicable to the specific obstetric interventions employed at these institutions or institutions similar to ones included in the CSL study.

There were racial/ethnic disparities in labor induction with NHB women being induced overall more often than any other racial/ethnic group, primarily due to increased rates of medical and obstetric complications. However, this pattern in labor induction changed after 34 weeks of gestation when controlling for a variety of sociodemographic factors as well as indications for delivery. Compared with all other racial/ethnic groups, NHW women were more likely to undergo non-medically indicated induction at term. Because labor induction may avoid the occurrence of stillbirth, whether this finding may explain, in part, the increased risk of stillbirth for black women at term and merits further research.

Acknowledgments

The Consortium on Safe Labor was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, through contract number HHSN267200603425C. Institutions involved in the Consortium include, in alphabetical order, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Burnes Allen Research Center, Los Angeles, CA; Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE; Georgetown University Hospital, MedStar Health, Washington, DC; Indiana University Clarian Health, Indianapolis, IN; Intermountain Healthcare and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY; MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH; Summa Health System, Akron City Hospital, Akron, OH; The EMMES Corporation, Rockville MD (Data Coordinating Center); University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL; University of Miami, Miami, FL; and University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this manuscript, which does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the NICHD. Biostatistical support for this project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds (grant number: UL1RR031975) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA), a trademark of DHHS, part of the Roadmap Initiative, “Re-Engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise.”

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;60(01):1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sparks PJ. Do biological, sociodemographic, and behavioral characteristics explain racial/ethnic disparities in preterm births? Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(09):1667–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willinger M, Ko C-W, Reddy UM. Racial disparities in stillbirth risk across gestation in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(05):469.e1–469.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka M, Jaamaa G, Kaiser M, et al. Racial disparity in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in New York State: a 10-year longitudinal population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(01):163–170. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AHRQ. National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cahill AG, Stamilio DM, Odibo AO, Peipert J, Stevens E, Macones GA. Racial disparity in the success and complications of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(03):654–658. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318163be22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(04):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guendelman S, Thornton D, Gould J, Hosang N. Obstetric complications during labor and delivery: assessing ethnic differences in California. Womens Health Issues. 2006;16(04):189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56(10):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy K, Grobman WA, Lee TA, Holl JL. Racial disparities in term induction of labor rates in Illinois. Med Care. 2008;46(09):900–904. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817924f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy K, Holl JL, Lee TA, Grobman WA. National trends and racial differences in late preterm induction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(05):458.e1–458.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murthy K, Grobman WA, Lee TA, Holl JL. Trends in induction of labor at early-term gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(05):435.e1–435.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimes DA. Epidemiologic research using administrative databases: garbage in, garbage out. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(05):1018–1019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f98300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, et al. Consortium on Safe Labor. Contemporary cesarean delivery practice in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(04):326.e1–326.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laughon SK, Zhang J, Grewal J, Sundaram R, Beaver J, Reddy UM. Induction of labor in a contemporary obstetric cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(06):486.e1–486.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(03):219–242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan YC. Multiple Imputation for Missing Data: Concepts and New Development (Version 9.0) Rockville, MD: SAS Institute Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDorman M, Kirmeyer S. NCHS Data Brief, No 16. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. The challenge of fetal mortality. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Sun L, Troendle J, Willinger M, Zhang J. Prepregnancy risk factors for antepartum stillbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(05):1119–1126. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f903f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spong CY, Mercer BM, D’alton M, Kilpatrick S, Blackwell S, Saade G. Timing of indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):323–333. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182255999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]