Abstract

We describe a selective and mild chemical approach to controlling RNA hybridization, folding, and enzyme interactions. Reaction of RNAs in aqueous buffer with an azide-substituted acylating agent (100-200 mM) yields several 2′-OH acylations per RNA strand in as little as 10 min. This poly-acylated (“cloaked”) RNA is strongly blocked from hybridization with complementary nucleic acids, from cleavage by RNA-processing enzymes, and from folding into active aptamer structures. Importantly, treatment with a water-soluble phosphine triggers a Staudinger reduction of the azide groups, resulting in spontaneous loss of acyl groups (“uncloaking”). This fully restores RNA folding and biochemical activity.

Keywords: cloaking, RNA, caging, acylation, Staudinger

Graphical abstract

Chemical switch for RNA: We describe simple selective chemical approach for control of RNA function. Polyacylation of 2′-OH groups with a nicotinyl-imidazole reagent (cloaking) switches off structure and biomolecular recognition. RNA is switched on again (uncloaking) by Staudinger reductions that remove the acyl groups.

The great complexity of RNA biology presents challenges to chemical and biological analysis. Beyond the better-studied messenger RNAs, the largest fraction of cellular RNA consists of noncoding species, including not only transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), but also a growing range of other long and short noncoding species,[1] including small nuclear RNAs (snRNA),[2] microRNAs (miRNA),[3] small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNA),[4] circular RNAs (circRNA),[5] and tRNA fragments (tRF).[6] The biological functions of a major fraction of these species remain to be characterized, and their interactions with other RNAs, proteins, and small molecules remain elusive. Recent advancements in RNA sequencing[7] and in structure mapping[8] have been important in characterizing RNAs, but the field will benefit greatly from new methods as well. For example, studies of interactions and changes that occur with RNA in time and space could benefit from methods to control structure and interactions in a chemically selective way. Moreover, the rapid rise in use of RNA as a diagnostic biomarker might also benefit from methods of controlling its properties in vitro.

RNA function can be studied with methods that temporarily suspend its activity. For example, light-based blocking (photocaging) strategies have been used recently in temporal control of RNA activity.[9] In this approach, a photolabile caging group is added onto one or multiple RNA bases,[10] phosphate groups[11] or 2′-OH groups of synthetic oligoribonucleotides.[12] Upon photoirradiation, the cage is released, restoring RNA function. Such photocaging strategies have been used to control and study gene expression[10,11b,13] and ribozyme function.[12b,14] While photodeblocking offers the potential advantage of spatially localized RNA activation, it carries the limitation of needing to protect the RNA from light during preparation and handling. A more significant issue is toxicity of intense short-wavelength light exposure in cell-based experiments.[15] Moreover, standard strategies require the application of caging only in chemically synthesized RNAs, with synthetically modified components. This limits applications to short RNA constructs that are not readily accessible to many biology laboratories, while longer transcribed or native RNAs cannot be studied. One strategy for photocaging of longer transcribed RNAs was reported in 2001 by Ando et al.;[11b] the method uses a diazo compound to react with backbone phosphate groups in RNAs via carbene chemistry. A significant drawback of the method is the instability of the phosphotriester products, leading to RNA fragmentation.[16] The method has not been demonstrated to block hybridization or folding, possibly due to the low numbers of modifications that can be appended.

Two chemical blocking strategies for RNA and DNA have been previously reported.[17] In this methods, one or several guanine bases are caged with a trichloroethyl (TCE)[17a] or 4-nitrobenzyl (NB)[17b] groups and incorporated into a nucleic acid strand during solid-phase synthesis. The cage can be released upon reduction of TCE group with Zn/AcOH, or NB group by treatment with sodium thiosulfate. These methods, however, can only be used on relatively short, synthetic nucleic acids.

We describe here a novel and versatile strategy for covalent acylation and de-acylation of RNA. Our approach is distinct from prior photocaging approaches in two important ways: it is carried out post-synthetically in a single step; and it is reversed chemically rather than by light. Different from previous RNA acylation reactions[8c,8d,18] we now show that the reaction of RNA with acylating reagent NAI-N3 (Figure 1a) can be carried out in high yields, with multiple acyl blocking groups appended per strand. We further show that this polyacylation (“cloaking”) can block RNA folding, small molecule binding, hybridization, and enzyme recognition. At a subsequent time, the unmodified RNA with native activity can be restored by bioorthogonal deacylation with a water-soluble phosphine (Figures 1b-c). Thus, this new cloaking and uncloaking strategy enables chemical control of RNA. The methodology is exceptionally simple and mild, and functions both with chemically synthesized or transcribed RNAs.

Figure 1.

Structure of RNA acylating reagent NAI-N3 and mechanism of RNA cloaking/uncloaking. (a) Structure of acylating agent NAI-N3 (1) (b) Multi-acylation of RNA 2′-OH groups (red) with 1. Polyacylation blocks hybridization and folding. Subsequent removal of those groups (“uncloaking”) by phosphine treatment restores RNA biophysical and biochemical activity. The byproduct is a lactam 2 (shown) and a phosphine oxide. (c) Mechanism of deacylation.

Design of a new de-acylation strategy

To achieve this blocking and unblocking, we adopted our recently developed water-soluble nicotinyl acylating agent NAI-N3,[18] but we completely changed its subsequent reactivity to enable de-acylation. Previously, the azide group in this reagent was used as a site for a “click” reaction with a biotin group, and the ester remained linked to the RNA. In the new work, we recognized that the azide group is ideally positioned to provide a handle for self-removal of the group from the RNA 2′-OH. Staudinger reduction of the azide could result in cyclization, releasing restored RNA and lactam 2 (Figure 1b-c). Azide reduction with phosphines has been studied for multiple biological and biotechnological applications: for example, for reduction of azidophenylalanine in proteins,[19] and as a reversible terminator in sequencing chemistry.[7] O-azidomethylbenzoyl groups were previously used in organic synthesis to protect alcohols and amines, and were released during the deprotection step with aryl phosphines.[20]

To test our proposed cloaking-uncloaking strategy with NAI-N3, we chose to study reactions initially with short transfer RNA-derived RNA fragments (tRFs).[6] tRFs represent an ideal research target due to their small size, diversity, and biological significance.[6] Initial reactions were carried out with 18 nucleotide (nt) tRNA fragments tRF-3005 and tRF-3004.[6a] In addition, to determine whether secondary structure influences possibility of RNA labeling, we designed tRF-3005 analogs (tRF-3005/8 and tRF-3005/4) incorporating hairpin architecture with 8 nt and 4 nt loops, respectively (see sequences in the Supporting Information (Table S1)). RNAs were labeled at their 5′-ends with Cy5 to facilitate analysis.

Prior acylation mapping studies were carried out at a level of <1 acyl group per RNA strand.[18] In the new cloaking strategy, much higher degrees of acylation were required, in order to block hybridization, folding, and intermolecular interactions. To test this, we prepared a high concentration (2 M) NAI-N3 stock solution in DMSO.[18] We incubated RNAs with 200 mM NAI-N3 at 37 °C for 2 h in HEPES buffer. Successful reaction was confirmed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in (Figure 2a, lanes 1 and 2) and quantified by MALDI-TOF MS (Figure 2b). Gratifyingly, we observed a range of 8 to 16 azidomethylnicotinyl (AMN) groups per 18 nucleotide-long tRF-3005 RNA (Figure 2b), order of magnitude higher acylation than achieved before with mapping experiments.[8,18] We found that the labeling extent depended on the number of accessible single-stranded 2′-OH groups (Figures S1-S2).[8c,8d,18] Hairpin tRF-3005/8 having 8 single-stranded nucleotides yielded acylated RNA with 4 to 10 labels (Figure S2 a-c), and reducing the loop size to 4 nt in tRF-3005/4 reduced this number to 2-7 AMN groups per strand (Figure S2 d-f). Importantly, the DNA analog of tRF-3005 showed very little acylation (<0.2 groups per strand, as estimated by MALDI-MS (Figure S3)), which is likely the result of minor reaction with a terminal hydroxyl group or a hydroxyl group of Cy5. Thus, the NAI-N3 reagent is highly selective for RNA over DNA, due to the reactive 2′-OH nucleophiles in the former. The data show that RNA acylation with NAI-N3 can be carried out conveniently in a single step, yielding high loading of acyl groups.

Figure 2.

Cloaking and uncloaking of tRF-3005 RNA. (a) PAGE gel showing untreated (lane 1), cloaked (lane 2), and uncloaked (DPBA, 1 h, 37 °C) (lane 3) tRF-3005. (b) MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of cloaked tRF-3005; numerals in red indicate numbers of adducts. See Figure S4 for details.

Next, we tested whether our proposed Staudinger reduction strategy could proceed efficiently for uncloaking of polyacylated RNA. Initial testing of a range of phosphines showed that most yielded high levels of uncloaking (Figure S4); we selected 2-(diphenylphosphino)benzoic acid[21] (DPBA 3), one of the best performers, for further studies. Incubation of cloaked RNA with 20 mM DPBA (Figure 3) at 37 °C in Tris buffer (with 20% DMSO to support DPBA solubility) resulted in removal of AMN groups in a time-dependent manner (Figure S5). We confirmed almost complete RNA uncloaking by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry after 6 hours of incubation (Figure S5-f), however, a significant level of RNA restoration was already observed after 1 h (Figure 2a (lane 3), and Figure S5c). Incubation with DPBA results in rapid reduction of azides; after 30 min incubation, no azides remained, and masses corresponding to the reduced amino adducts were seen. The limiting step is the intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the intermediate, but extended incubation resulted in loss of the majority of those intermediates (Figure S5). Importantly, complete loss of these groups is not required for restoration of activity (vide infra). As expected for the new designed self-deprotection mechanism, lactam 2 is a byproduct, as confirmed by LC-MS (Figure S7).

Figure 3.

Structures of phosphines used in this study.

Blocking and triggering hybridization

The next important question to address was whether polyacylation of tRF RNAs could block their biophysical and biochemical properties. Although acyl groups have been shown to block progress of a reverse transcriptase enzyme,[8] they have not been tested for their effect on duplex stability. First, we sought to see if cloaking can be used to control hybridization to a complementary oligonucleotide. To quantify hybridization, we designed a molecular beacon (MB) assay,[22] employing a MB complementary to tRF-3005 (Table S1). For untreated RNA, we observed a large increase in fluorescence upon addition of tRF-3005 (Figure 4, green line and bar). Cloaking tRF-3005 with NAI-N3 largely abolished the MB signal (>95% blocked; Figure 4, red line and bar), establishing that polyacylation strongly impairs hybridization. Significantly, uncloaking the RNA with DPBA for 1 h at 37 °C completely restored molecular beacon fluorescence (Figure 4, blue line and bar). Thus, the results show that the acylation cloaking – uncloaking strategy provides a high degree of control over RNA hybridization.

Figure 4.

Cloaking and uncloaking of RNA can be used to control its hybridization, as measured by molecular beacon assay. (a) Mechanism of NAI-N3 enabled hybridization control. (b) Plot of effect of cloaking/uncloaking on MB fluorescence. Green line: Increase of fluorescence of MB upon its incubation with untreated tRF-3005 RNA; red, cloaked tRF-3005; blue, signal after uncloaking (20 mM DPBA (3), 1h, 37 °C). Data are representative of 3 experiments; (c) Molecular beacon (MB) hybridization to tRF-3005 RNA at 37 ˚°C is strongly suppressed by cloaking as measured by MB fluorescence (background subtracted). Green bar, untreated tRF-3005; red, cloaked tRF-3005; blue, uncloaked tRF-3005 (20 mM DPBA, 1h, 37 °C). Error bars represent ±s.d. and p-values: *** p<0.001, * p<0.05.

Control of RNA cleavage by enzymes

We proceeded to test whether cloaking of an RNA could hinder its recognition and cleavage by nucleic acid or protein enzymes. In DNAzyme 10-23,[23] two segments of DNA complementary to the RNA of interest flank a 15 nt core that catalyzes cleavage of a 5′-Pu-Py-3′ linkage in RNA. To measure DNAzyme activity, we chose tRF-3004 RNA (Table S1) which conveniently has a 5′-A-U-3′ cleavage site in the center. 10-23-promoted cleavage of RNA was analyzed by PAGE. For untreated RNA, we found that the DNAzyme cleaves ≈15% tRF-3004 in 30 min (Figure 5a and Figure S8). Cloaking RNA with NAI-N3 almost completely abolishes RNA cleavage, indicating failure of the DNAzyme to recognize the RNA. Uncloaking tRF-3004 by incubation with 20 mM DPBA (3 h, 37 °C) nearly completely restored the amount of RNA cleaved in 30 min (Table S3). Similar results were also seen with a second DNAzyme with a different target sequence (Figure S9). We also found that cloaking tRF-3005 partially protects it from degradation by Ribonuclease H (RNase H). This enzyme recognizes and degrades RNA when it is hybridized to its DNA complement.[24] Data showed that RNase H almost completely degrades non-cloaked RNA in the presence of its DNA complement after 30 min (Figure 5b and Figure S10). The experiments show that the amount of cloaked RNA cleaved after 30 min is only about a half that of control RNA (Figure 5b, Table S4). Finally, uncloaking tRF-3005 with DPBA completely restored the RNase H cleavage of RNA (Figure 5b, Table S4 and Figure S10). Overall, we find that acylation-based cloaking can act as a strong mechanism for blocking enzymatic recognition and cleavage of RNA, and that uncloaking efficiently restores biochemical activity.

Figure 5.

Cloaking protects RNA from cleavage by enzymes that require hybridization, while uncloaking restores enzymatic cleavage. (a) Mechanism of NAI-N3 mediated RNA protection from cleavage by DNAzyme 10-23. (b) NAI-N3-treated RNA slows cleavage by the 10-23 DNAzyme: bar chart represents tRF-3004 fraction cleaved after 30 min incubation with 25 nM DNAzyme 10-23: green, untreated tRF-3004 RNA, red, cloaked RNA, blue, uncloaked RNA (20 mM DPBA, 3 h, 37 °C). (c) Acylated RNA is a poor substrate for HIV-1 RNase H: bar chart represents tRF-3005 fraction cleaved after 30 min incubation with RNase H as determined by PAGE: green, untreated tRF-3005 RNA, red, cloaked RNA, blue, uncloaked RNA (20 mM DPBA, 3 h, 37 °C). Error bars: ±s.d. and p-values: ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, ns. - not significant.

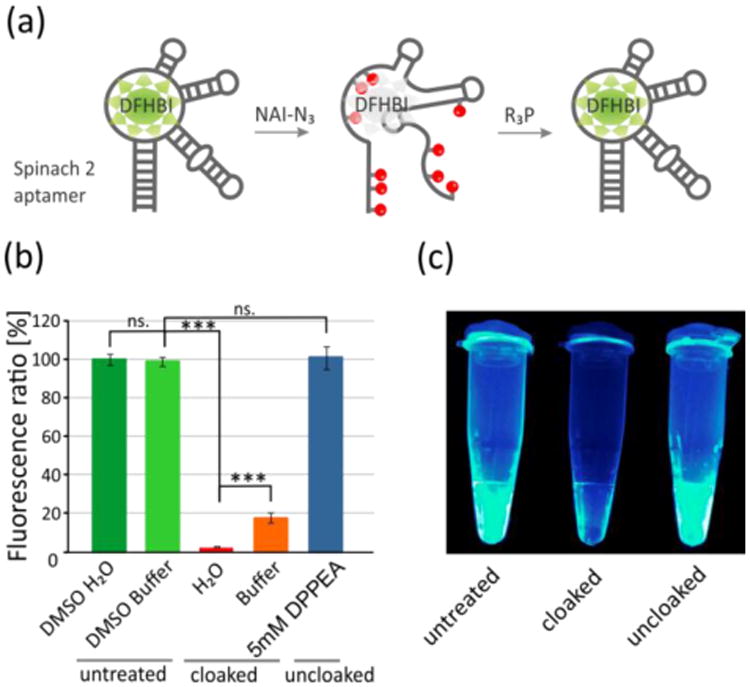

Control of folding of RNA aptamers

The above experiments were carried out primarily with short, synthetic, single-stranded oligoribonucleotides. However, many biologically relevant RNAs of interest are considerably longer than this, and they often fold into secondary and tertiary structures that confer their biophysical and biochemical properties. Thus, we aimed to test whether a longer transcribed RNA could be efficiently cloaked and controlled by polyacylation with NAI-N3. The Spinach RNA aptamer was selected as an ideal test case, as it is ∼100 nt in length and folds into its active structure, binding the DFHBI chromophore and yielding an intense green fluorescence signal in its folded state.[25] We transcribed and purified a 102 nt Spinach construct (Table S1), and confirmed that the Spinach RNA yields a strong fluorescence light-up signal (250 fold) with DFHBI in vitro in folding buffer (37 °C, 1 h) (Figure S11a). Comparable results were obtained with F-30 Broccoli aptamers[26] as well (Figure S11b).

Next, we treated the RNA with 0.1 M NAI-N3 for 10 min - 1 h (pH 7.5 MOPS buffer). This yielded cloaked RNA with a loss of 85% of the original signal (see spectra in Figure S11). NAI-N3 was originally used as a structure-specific reagent that is selective for single-stranded nucleotides.[8c,8d,18] Since in principle this reaction would yield little acylation in folded regions, we next tested acylation in low ionic strength solution, to destabilize folding and enable reaction in previously folded regions.[25a,27] The resulting RNA cloaked under these low-salt conditions yielded almost complete loss of DFHBI signal (98.6% loss, Figure 6), indicating virtually complete disruption of folded aptamer structure and/or ligand binding ability. We observed that acylation for only 10 min yielded this strong disruption under these reaction conditions. Mock treatments with DMSO alone yielded no disruption of signal. Next, we proceeded to test uncloaking of the Spinach RNA, treating it with several phosphines for varied times (Figure S12) and concentrations (Figure S13). Interestingly, the folded RNA showed more selectivity among phosphines in uncloaking (Figure S14). Treatment with DPPEA for as little as 10 min completely restored fluorescence of the Spinach RNA with DFHBI (100 % of untreated RNA, Figure S12). Notably, PAGE analysis of the 102 nt RNA after the uncloaking procedure (Figure S15) confirms no degradation of the RNA. Thus, we confirm that our cloaking/uncloaking strategy can be used successfully to control function of a transcribed RNA that relies on folding for its activity.

Figure 6.

Acylation-based control of RNA folding. (a) Mechanism of NAI-N3 driven control of RNA folding using Spinach 2 aptamer. (b) Spinach RNA (102 nt) was treated with 100 mM NAI-N3 in buffer, resulting in a loss of fluorescence signal (orange bar). Treatment with NAI-N3 under low ionic strength conditions yielded greater loss of signal (red). Subsequent treatment with a phosphine (DPPEA, 5 mM, 1 h), yielded 100% recovery of signal (dark blue). Control treatment of RNA by DMSO in either buffer or water shows no significant changes. Error bars represent ±s.d. and p-values: *** p<0.001, ns. -not significant; (c) Fluorescence of Spinach cloaking reactions, from left to right: untreated RNA, cloaked, and uncloaked RNA (DPPEA, 5 mM, 1 h).

Our experiments establish the use of NAI-N3 acylating agent combined with phosphines to reversibly block interactions of RNA with other molecules. Due to the controlled reactivity and aqueous solubility of NAI-N3, high-density loading of RNAs is possible, at least to a level of >50% of the 2′-OH groups. The resulting AMN groups on the RNA destabilize duplex structures involving the RNA, and thus block hybridization effectively. Further, the acyl groups can block enzymatic recognition of the RNA and significantly change rates of reaction, including RNase H activity and DNAzyme cleavage. Importantly, AMN groups that cloak RNA activity can be removed under mild conditions that restore free RNA and its biochemical activity.

The current chemical cloaking/uncloaking strategy suggests multiple possible future in vitro applications. Examples include orthogonal RNA activities, in which some RNAs are temporarily inactivated while others are not, or designating specific timing of RNA activity in an assay. An analogous temporary biomolecular inactivation is currently used for proteins in PCR amplification, with “hot start” polymerase enzymes.[28] In addition, the selectivity of the current acylation chemistry might enable selective control of RNA in the presence of DNA, which can otherwise be difficult to achieve. Further, since acylation blocks hybridization, it could be used to reversibly block RNA structure formation and trigger folding temporally. More studies are planned to test some of these applications. Further in the future, it is possible that such chemical blocking and unblocking of RNAs could be carried out in living cells, to trigger biological activity upon addition of a chemical reductant. While an intriguing possibility, this will require the development of cell-permeable, low-toxicity reductants that can reduce the azide of NAI-N3 (or related reagents) and achieve de-acylation efficiently without adverse effects on cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the U.S. National Institutes of Health (GM110050, GM106067, and CA217809) for support.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.Cech TR, Steitz JoanA. Cell. 157:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butcher SE, Brow DA. Biochem Soc T. 2005;33:447. doi: 10.1042/BST0330447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Hannon GJ. Nature. 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wilson RC, Doudna JA. Ann Rev Biophys. 2013;42:217–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dieci G, Preti M, Montanini B. Genomics. 2009;94:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen LL. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:205–211. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Lee YS, Shibata Y, Malhotra A, Dutta A. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2639–2649. doi: 10.1101/gad.1837609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Keam SP, Hutvagner G. Life. 2015;5:1638–1651. doi: 10.3390/life5041638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo J, Xu N, Li Z, Zhang S, Wu J, Kim DH, Sano Marma M, Meng Q, Cao H, Li X, Shi S, Yu L, Kalachikov S, Russo JJ, Turro NJ, Ju J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9145–9150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804023105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Merino EJ, Wilkinson KA, Coughlan JL, Weeks KM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4223–4231. doi: 10.1021/ja043822v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Low JT, Weeks KM. Methods. 2010;52:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Spitale RC, Crisalli P, Flynn RA, Torre EA, Kool ET, Chang HY. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:18–20. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Spitale RC, Flynn RA, Torre EA, Kool ET, Chang HY. WIREs RNA. 2014;5:867–881. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deiters A. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikat V, Heckel A. RNA. 2007;13:2341–2347. doi: 10.1261/rna.753407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Wu L, Pei F, Zhang J, Wu J, Feng M, Wang Y, Jin H, Zhang L, Tang X. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:12114–12122. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ando H, Furuta T, Tsien RY, Okamoto H. Nat Genet. 2001;28:317–325. doi: 10.1038/ng583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang X, Feng M, Xiao L, Tong A, Xiang Y. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:444–451. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Chaulk SG, MacMillan AM. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1052–1058. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chaulk SG, MacMillan AM. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3173–3178. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.13.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Wu L, Wang Y, Wu J, Lv C, Wang J, Tang X. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:677–686. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Govan JM, Young DD, Lusic H, Liu Q, Lively MO, Deiters A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:10518–10528. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Casey JP, Blidner RA, Monroe WT. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2009;6:669–685. doi: 10.1021/mp900082q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Shah S, Rangarajan S, Friedman SH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:1328–1332. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Kobitski AY, Schäfer S, Nierth A, Singer M, Jäschke A, Nienhaus GU. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:12800–12806. doi: 10.1021/jp402005m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee HW, Robinson SG, Bandyopadhyay S, Mitchell RH, Sen D. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Höbartner C, Silverman SK. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:7305–7309. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Clydesdale GJ, Dandie GW, Muller HK. Immunol Cell Biol. 2001;79:547–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2001.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McMillan TJ, Leatherman E, Ridley A, Shorrocks J, Tobi SE, Whiteside JR. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:969–976. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.8.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blidner RA, Svoboda KR, Hammer RP, Monroe WT. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:431–440. doi: 10.1039/b801532e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Höbartner C, Mittendorfer H, Breuker K, Micura R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3922–3925. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ikeda M, Kamimura M, Hayakawa Y, Shibata A, Kitade Y. ChemBioChem. 2016;17:1304–1307. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spitale RC, Flynn RA, Zhang QC, Crisalli P, Lee B, Jung JW, Kuchelmeister HY, Batista PJ, Torre EA, Kool ET, Chang HY. Nature. 2015;519:486–490. doi: 10.1038/nature14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Park CM, Niu W, Liu C, Biggs TD, Guo J, Xian M. Org Lett. 2012;14:4694–4697. doi: 10.1021/ol3022484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schütz V, Mootz HD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:4113–4117. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Naganathan S, Ye S, Sakmar TP, Huber T. Biochemistry. 2013;52:1028–1036. doi: 10.1021/bi301292h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Efimov VA, Aralov AV, Klykov VN, Chakhmakhcheva OG. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2009;28:846–865. doi: 10.1080/15257770903170286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Efimov VA, Aralov AV, Grachev SA, Chakhmakhcheva OG. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2010;36:628–633. doi: 10.1134/s1068162010050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo J, Liu Q, Morihiro K, Deiters A. Nat Chem. 2016;8:1027–1034. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tyagi S, Kramer FR. Nat Biotech. 1996;14:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santoro SW, Joyce GF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4262–4266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cerritelli SM, Crouch RJ. FEBS J. 2009;276:1494–1505. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.a) Warner KD, Chen MC, Song W, Strack RL, Thorn A, Jaffrey SR, Ferré-D'Amaré AR. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:658–663. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Paige JS, Wu KY, Jaffrey SR. Science. 2011;333:642. doi: 10.1126/science.1207339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.a) Filonov GS, Moon JD, Svensen N, Jaffrey SR. J Amer Chem Soc. 2014;136:16299–16308. doi: 10.1021/ja508478x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Filonov GS, Kam CW, Song W, Jaffrey SR. Chemistry & Biology. 2015;22:649–660. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tinoco I, Bustamante C. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:271–281. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Aquila RT, Bechtel LJ, Videler JA, Eron JJ, Gorczyca P, Kaplan JC. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3749. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.13.3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.