Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether oral fluoroquinolone use is associated with an increased risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection.

Design

Nationwide historical cohort study using linked register data on patient characteristics, filled prescriptions, and cases of aortic aneurysm or dissection.

Setting

Sweden, July 2006 to December 2013.

Participants

360 088 treatment episodes of fluoroquinolone use (78%ciprofloxacin) and propensity score matched comparator episodes of amoxicillin use (n=360 088).

Main outcome measures

Cox regression was used to estimate hazard ratios for a first diagnosis of aortic aneurysm or dissection, defined as admission to hospital or emergency department for, or death due to, aortic aneurysm or dissection, within 60 days from start of treatment.

Results

Within the 60 day risk period, the rate of aortic aneurysm or dissection was 1.2 cases per 1000 person years among fluoroquinolone users and 0.7 cases per 1000 person years among amoxicillin users. Fluoroquinolone use was associated with an increased risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection (hazard ratio 1.66 (95% confidence interval 1.12 to 2.46)), with an estimated absolute difference of 82 (95% confidence interval 15 to 181) cases of aortic aneurysm or dissection by 60 days per 1 million treatment episodes. In a secondary analysis, the hazard ratio for the association with fluoroquinolone use was 1.90 (1.22 to 2.96) for aortic aneurysm and 0.93 (0.38 to 2.29) for aortic dissection.

Conclusions

In a propensity score matched cohort, fluoroquinolone use was associated with an increased risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection. This association appeared to be largely driven by aortic aneurysm.

Introduction

Fluoroquinolones remain among the most commonly used antibiotics globally, and about 30 million outpatient prescriptions for fluoroquinolones are issued per year in the United States alone.1 2 Fluoroquinolone use is associated with an increased risk of tendon disorders, including Achilles tendon rupture and tendinopathy.3 4 The mechanisms behind these adverse events, which are recognised in a boxed warning, are thought to implicate non-antimicrobial properties of fluoroquinolones. These antibiotics have been shown to induce degradation of collagen and other structural components of the extracellular matrix by stimulating the activity of matrix metalloproteinases,5 6 reduce de novo production of collagen,7 and induce oxidative stress in tendon cells.8

Rupture and dissection of the aorta are life threatening medical emergencies that need prompt intervention, often involving surgery. The integrity of the human aorta heavily depends on an intact extracellular matrix, and the pathophysiology of aortic aneurysm is known to involve excessive tissue breakdown through matrix metalloproteinases.9 10 Two recent observational studies have raised concern that fluoroquinolone antibiotics could increase the risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection.11 12 Although limitations in study design have not resulted in firm conclusions, with both studies reporting more than a twofold increased risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection associated with fluoroquinolone exposure, these data have prompted the European Medicines Agency to initiate a safety assessment.13

We conducted a nationwide, register based cohort study in Sweden to investigate the risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection, comparing treatment episodes of fluoroquinolone use with episodes of amoxicillin use.

Methods

We conducted a cohort study based on linked nationwide data from Swedish registers, (July 2006 to December 2013). We investigated the risk of a first diagnosis of aortic aneurysm or dissection (admission to hospital or emergency department for aortic aneurysm or dissection, or death due to aortic aneurysm or dissection) associated with oral fluoroquinolone use, as compared with amoxicillin use, within a 60 day period from start of treatment. We used two major strategies to control for confounding. To account for potential confounding by indication (infection, or unmeasured factors associated with receipt of antibiotic treatment, might be associated with increased risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection), we used an active comparator design, with amoxicillin as the comparator. Amoxicillin is an antibiotic with no known association with aortic aneurysm or dissection, and its approved indications largely overlap with those of fluoroquinolones, including respiratory and urinary tract infections. To control for potential confounding from differences in baseline health status, we used a propensity score matched design, taking into account demographic characteristics, medical history, concomitant use of other medical drugs, and measures of healthcare use.

Sources of data

We used the following data sources:

National Prescribed Drug Register, which captures all prescriptions filled at all Swedish pharmacies since July 2005, including details pertaining to the specific drug and the date the prescription was filled.14

National Patient Register, which captures data for all hospital admissions and outpatient and emergency department visits in Sweden, including physician assigned diagnoses according to ICD-10 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision) as well as data for surgical procedures.15

Statistics Sweden, which captures data for demographic characteristics.

Swedish Cause of Death Register, which captures all causes of death in Sweden and is based on death certificates.

Cohort

The source population included all adults in Sweden who received a prescription for fluoroquinolones or amoxicillin during the study and who were aged 50 years or older. From this group, we identified treatment episodes of fluoroquinolone and amoxicillin use in individuals who:

Had no previous diagnosis of aortic aneurysm or dissection (data available from 1997 onwards)

Did not use study antibiotics in the previous 120 days

Were not admitted to hospital in the previous 120 days (information on inhospital antibiotic exposure was not available)

Did not receive multiple antibiotics (any) on the same day

Did not have a diagnosis indicating endstage illness or drug/alcohol misuse (web table 1)

Had used at least one prescription drug in the past year (to ensure some degree of activity in the healthcare system).

Previous studies reporting associations between fluoroquinolones and aortic aneurysm or dissection used risk periods of approximately 37 and 60 days, respectively.11 12 Given these reports, our risk period of interest was defined as a 60 day period from start of treatment (days 1 to 60, starting from the date when the prescription was filled). We also included a secondary analysis investigating the subsequent 60 days (days 61 to 120). To explore the timing of the association, the 60 day risk period was divided into 10 day intervals, assessing the number of events in each interval.

Propensity score

To control for potential confounders, treatment episodes of fluoroquinolone and amoxicillin use were matched in a 1:1 ratio on the basis of propensity scores using the 5->1 digit greedy matching algorithm.16 17 The propensity score for fluoroquinolone exposure was estimated by a logistic regression model, including 47 covariates as predictors, covering demographic information, medical history, prescription drug use, and healthcare use (web table 2). One covariate, region of residence, had missing values (0.1% missing); missing values were handled by inclusion of a missing value category.18 We assessed covariate balance in the matched cohort by checking standardised differences between the groups; we considered a covariate to be well balanced if the standardised difference was less than10%.

Aortic aneurysm or dissection

The primary outcome was defined as a first diagnosis of aortic aneurysm or dissection, including thoracic, thoracoabdominal, and abdominal aneurysm (with or without rupture) and aortic dissection (ICD-10 codes in web table 3). In a secondary analysis, the outcomes of any aortic aneurysm and dissection, respectively, were analysed separately. The outcome was identified as the primary diagnosis (that is, the main diagnosis) associated with admission to hospital or emergency department (as captured through the National Patient Register) or as the underlying cause of death (as recorded in the Cause of Death Register). In a review of medical records of thoracic aortic aneurysms and aortic dissection identified through these two registers, 165 (97%) of 170 cases involved a confirmed diagnosis of any aortic aneurysm.19 In a validation study of the Danish National Patient Register, which is comparable in content and structure to its Swedish counterpart owing to similarities in organisation of the registers and healthcare systems, the positive predictive values for a register based strategy for capture of cases were 92% for aortic dissection and 100% for aortic aneurysm.20

The outcome definition was designed to capture the first clinical encounter of aortic aneurysms or dissections that were likely to be severe and symptomatic, because these events had prompted admission to hospital or emergency department or had led to death. Thus, aortic aneurysm or dissection diagnosed in outpatient care and registered as a secondary diagnosis in any type of care were not considered to represent outcome events.

Statistical analysis

Patients contributed person time from the date a prescription was filled, to the date of an outcome event, end of follow-up (120 days), end of study period (31 December 2013), hospital admission, death, or new prescription for a study antibiotic. A single patient could contribute with multiple treatment episodes to the cohort; these episodes were all unique and never overlapped in time, and the outcome event could occur only once in each patient. Hence, assumptions of statistical independence were not violated. Cox proportional hazards regression, with days since start of treatment as the time scale, was used to estimate the hazard ratio for aortic aneurysm or dissection, comparing episodes of fluoroquinolone and amoxicillin use. We assessed the proportional hazards assumption by measuring the interaction between treatment status and time scale using a Wald test.21 The absolute rate difference for the 60 day risk period was estimated as (hazard ratio−1)×incidence in the amoxicillin group,22 and reported as the number of cases per million treatment episodes.

We conducted subgroup analyses according to sex and age. In preplanned sensitivity analyses, the outcome definition was varied, assuming that more restrictive definitions might be more specific for the outcome or reflect a more severe disease phenotype. The outcome was restricted to cases of aortic aneurysm or dissection:

With rupture or dissection alone (not without rupture or dissection)

Associated with admission to hospital alone (not emergency department) or in which aortic aneurysm or dissection were the underlying cause of death

Involving patients who had had aortic surgery or died within 30 days of the date of diagnosis or in whom aortic aneurysm or dissection were the underlying cause of death (web table 4).

To assess potential unmeasured confounding, we also analysed the risk of death from any cause; an observed difference in overall mortality between patients treated with fluoroquinolones and amoxicillin would be likely to reflect residual differences in baseline health status or severity of indication (that is, infection) between the groups, rather than a treatment effect. We also conducted a post hoc sensitivity analysis restricted to the first episode included in the study for each individual patient. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4. Results were considered significant when 95% confidence intervals did not overlap 1.0.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in the development of the research question, the outcome measures, or the design of the study. As a study based on nationwide registers that implement routine registration, no patients were involved in recruitment or conduct of the study, and results will not be disseminated to study participants.

Results

Cohort

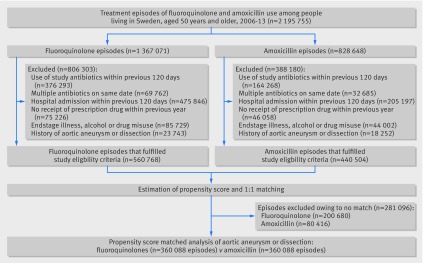

Among the source population of 2 333 219 treatment episodes of fluoroquinolone or amoxicillin use, the study eligibility criteria were met for 560 768 episodes of fluoroquinolone use and 440 504 episodes of amoxicillin use (fig 1). After propensity score estimation and 1:1 matching, the study cohort included 720 176 treatment episodes (360 088 in each group). Of the 360 088 episodes of fluoroquinolone use, most were with ciprofloxacin (78%), followed by norfloxacin (20%), and other fluoroquinolones (2%). Baseline characteristics of patients with episodes of fluoroquinolone and amoxicillin use before and after propensity score matching are shown in web table 5 and table 1, respectively. In the matched cohort, all baseline characteristics, as assessed by standardised differences, were well balanced between the groups. The mean follow-up in the 60 day risk period was 52 days (standard deviation 17) days in the fluoroquinolone group and 55 days (14) in the amoxicillin group. The proportional hazards assumption was not violated (P=0.34 for primary outcome analysis).

Fig 1.

Nationwide cohort of patients in Sweden with treatment episodes of fluoroquinolone use and amoxicillin use, 2006-13. Values for exclusion criteria do not add up to totals because some episodes were excluded for more than one reason

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with treatment episodes of oral fluoroquinolone use and amoxicillin use included in 1:1 propensity score matched study cohort. Data are no (%) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Oral fluoroquinolones (n=360 088)* |

Amoxicillin (n=360 088)† |

Standardised difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 162 807 (45) | 162 641 (45) | 0.1 |

| Age (years, mean (standard deviation)) | 67.9 (10.8) | 68.0 (10.4) | 0.5 |

| Region of residence | |||

| Stockholm metropolitan area | 91 831 (26) | 90 777 (25) | 0.7 |

| Rest of mid-Sweden | 66 294 (18) | 66 674 (19) | 0.3 |

| Southern Sweden metropolitan areas | 60 176 (17) | 60 015 (17) | 0.1 |

| Rest of southern Sweden | 112 523 (31) | 113 067 (31) | 0.3 |

| Northern Sweden | 28 825 (8) | 29 122 (8) | 0.3 |

| Missing | 439 (0.1) | 433 (0.1) | 0.0 |

| Medical history | |||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 13 509 (4) | 13 427 (4) | 0.1 |

| Other ischaemic heart disease | 37 249 (10) | 37 077 (10) | 0.2 |

| Heart failure or cardiomyopathy | 18 877 (5) | 19 040 (5) | 0.2 |

| Valve disorders | 9945 (3) | 10 067 (3) | 0.2 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 20 388 (6) | 20 281 (6) | 0.1 |

| Arterial disease | 9023 (3) | 9002 (3) | 0.0 |

| Arrhythmia | 37 073 (10) | 37 005 (10) | 0.1 |

| Cardiac surgery or invasive cardiac procedure in previous year | 17 835 (5) | 17 817 (5) | 0.0 |

| Lung disease | 34 688 (10) | 34 989 (10) | 0.3 |

| Cancer | 38 714 (11) | 38 234 (11) | 0.4 |

| Cancer in previous year | 24 491 (7) | 24 038 (7) | 0.5 |

| Liver disease | 3793 (1) | 3754 (1) | 0.1 |

| Renal disease | 9739 (3) | 9747 (3) | 0.0 |

| Rheumatic disease | 16 880 (5) | 16 967 (5) | 0.1 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 22 069 (6) | 22 155 (6) | 0.1 |

| Prescription drug use in previous year | |||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker | 117 137 (33) | 117 166 (33) | 0.0 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 63 491 (18) | 63 760 (18) | 0.2 |

| Loop diuretic | 50 204 (14) | 50 377 (14) | 0.1 |

| Other diuretic | 51 656 (14) | 51 971 (14) | 0.2 |

| β blocker | 115 070 (32) | 114 998 (32) | 0.0 |

| Digoxin | 8635 (2) | 8794 (2) | 0.3 |

| Nitrates | 32 136 (9) | 32 178 (9) | 0.0 |

| Platelet inhibitor | 94 148 (26) | 94 104 (26) | 0.0 |

| Anticoagulant | 26 473 (7) | 26 730 (7) | 0.3 |

| Lipid lowering drug | 100 573 (28) | 100 584 (28) | 0.0 |

| Oral antidiabetic drug | 30 529 (9) | 30 485 (9) | 0.0 |

| Insulin | 19 422 (5) | 19 308 (5) | 0.1 |

| Antidepressant | 60 234 (17) | 60 524 (17) | 0.2 |

| Antipsychotic | 8185 (2) | 8078 (2) | 0.2 |

| Anxiolytic, hypnotic, or sedative drug | 110 339 (31) | 110 282 (31) | 0.0 |

| β2 agonist inhalant | 42 946 (12) | 43 000 (12) | 0.0 |

| Anticholinergic inhalant | 19 876 (6) | 20 101 (6) | 0.3 |

| Glucocorticoid inhalant | 56 389 (16) | 56 219 (16) | 0.1 |

| Oral glucocorticoid | 55 767 (16) | 55 688 (16) | 0.1 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug | 104 860 (29) | 104 913 (29) | 0.0 |

| Opiate | 76 958 (21) | 77 291 (22) | 0.2 |

| Systemic hormone replacement therapy | 64 506 (18) | 64 474 (18) | 0.0 |

| No of drugs used | |||

| 1-2 | 78 004 (22) | 78 221 (22) | 0.1 |

| 3-5 | 114 617 (32) | 114 664 (32) | 0.0 |

| 6-9 | 104 278 (29) | 104 405 (29) | 0.1 |

| ≥10 | 63 189 (18) | 62 798 (18) | 0.3 |

| Non-study antibiotic in previous 120 days | 102 423 (28) | 100 711 (28) | 1.1 |

| Healthcare use | |||

| Hospital admission due to cardiovascular causes in previous year | 16 352 (5) | 16 361 (5) | 0.0 |

| Hospital admission due to non-cardiovascular causes in previous year | 104 353 (29) | 104 121 (29) | 0.1 |

| Outpatient contact due to cardiovascular causes in previous year | 27 862 (8) | 27 880 (8) | 0.0 |

| Outpatient contact due to non-cardiovascular causes in previous year | 191 604 (53) | 191 987 (53) | 0.2 |

| Emergency department visit in previous 30 days | 17 992 (5) | 17 534 (5) | 0.6 |

Baseline characteristics of patients before matching are shown in web table 5.

Total no of patients=282 212.

Total no of patients=279 337.

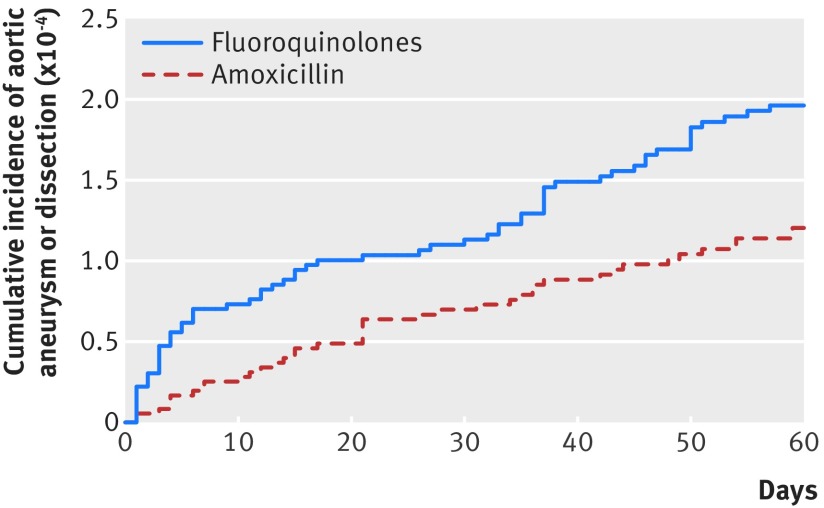

Risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection

In the 60 day risk period, there were 64 cases of aortic aneurysm or dissection among 360 088 treatment episodes of fluoroquinolone use (incidence 1.2 per 1000 person years), compared with 40 cases among 360 088 treatment episodes of amoxicillin use (0.7 per 1000 person years). The cumulative incidence of aortic aneurysm or dissection at 60 days was 2.0×10−4 for episodes of fluoroquinolone use and 1.2×10−4 for episodes of amoxicillin use (fig 2). There was an increased risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection associated with fluoroquinolone use (hazard ratio 1.66; 95% confidence interval 1.12 to 2.46). This increase corresponded to an absolute difference of 82 (95% confidence interval 15 to 181) cases of aortic aneurysm or dissection per 1 million treatment episodes in the 60 day risk period.

Fig 2.

Cumulative incidence of aortic aneurysm or dissection within 60 day risk period from start of study treatment

In a secondary analysis, there was no increased risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection associated with fluoroquinolone exposure in the period of 61-120 days from start of treatment (hazard ratio 0.67; 95% confidence interval 0.40 to 1.11). In another secondary analysis, the 60 day risk period was divided into 10 day intervals to explore the timing of the association (table 2). Of 64 cases of aortic aneurysm among patients treated with fluoroquinolones, 26 (41%) occurred in the first 10 days from start of treatment.

Table 2.

No of events of aortic aneurysm or dissection within the primary 60 day risk period, divided into 10 day intervals since start of treatment with oral fluoroquinolones, compared with amoxicillin*

| 10 day interval | Oral fluoroquinolones (n=360 088) | Amoxicillin (n=360 088) |

|---|---|---|

| 1-10 | 26 | 9 |

| 11-20 | 9 | 8 |

| 21-30 | 3 | 7 |

| 31-40 | 12 | 6 |

| 41-50 | 6 | 5 |

| 51-60 | 8 | 5 |

Propensity score matched (1:1 ratio) cohort. Propensity scores were based on 47 covariates including demographic characteristics, medical history, concomitant use of other medical drugs, and measures of healthcare use (that is, baseline characteristics shown in table 1).

In a secondary analysis, the hazard ratio for the association with fluoroquinolone use was 1.90 (95% confidence interval 1.22 to 2.96) for aortic aneurysm and 0.93 (0.38 to 2.29) for aortic dissection (web table 6). Of the cases of aortic aneurysm or dissection that occurred among fluoroquinolone users, most were abdominal aneurysm, followed by thoracic or thoracoabdominal aneurysm (web table 6).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Table 3 shows results of subgroup and sensitivity analyses. In subgroup analyses, the hazard ratios with fluoroquinolone use did not differ significantly between women and men and between subgroups of patients aged 50-64 years and those aged 65 years and above. In sensitivity analyses, the hazard ratios for the association between fluoroquinolone use and aortic aneurysm or dissection were in line with that of the primary analysis when the outcome was restricted to cases:

Table 3.

Results of subgroup and sensitivity analyses of the risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection associated with oral fluoroquinolone use as compared with amoxicillin use*

| Analysis† | Oral fluoroquinolones (n=360 088) |

Amoxicillin (n=360 088) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

P for homogeneity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of events |

No of events per 1000 person years | No of events |

No of events per 1000 person years | |||

| Subgroup analyses‡ | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 23 | 0.8 | 11 | 0.4 | 2.14 (1.04 to 4.39) | 0.41 |

| Male | 41 | 1.8 | 29 | 1.2 | 1.48 (0.92 to 2.39) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 50-64 years | 11 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.3 | 1.58 (0.61 to 4.07) | 0.89 |

| ≥65 years | 53 | 1.9 | 33 | 1.1 | 1.70 (1.10 to 2.62) | |

| Sensitivity analyses, variation of outcome definition | ||||||

| Cases with dissection or rupture alone | 31 | 0.6 | 22 | 0.4 | 1.45 (0.84 to 2.51) | — |

| Cases associated with admission to hospital or in which aortic aneurysm or dissection were the underlying cause of death |

56 | 1.1 | 36 | 0.7 | 1.61 (1.06 to 2.45) | — |

| Cases involving patients who had had aortic surgery or died within 30 days of diagnosis or in whom aortic aneurysm or dissection were the underlying cause of death | 43 | 0.8 | 29 | 0.5 | 1.53 (0.96 to 2.45) | — |

Propensity score matched (1:1 ratio) cohort. Propensity scores were based on 47 covariates including demographic characteristics, medical history, concomitant use of other medical drugs, and measures of healthcare use (that is, baseline characteristics shown in table 1).

All analyses were conducted for a 60 day risk period following start of treatment.

The outcome was defined as admission to hospital or emergency department with an incident diagnosis of aortic aneurysm, with or without rupture, or dissection, or death due to aortic aneurysm or dissection.

With dissection or rupture alone

Associated with admission to hospital alone (not emergency department) or in which aortic aneurysm or dissection were the underlying cause of death

Involving patients who had had aortic surgery or died within 30 days of diagnosis or in whom aortic aneurysm or dissection were the underlying cause of death.

The hazard ratio for death from any cause associated with fluoroquinolone use, as compared with amoxicillin, was 1.02 (95% confidence interval 0.97 to 1.08). In a post hoc sensitivity analysis restricted to the first episode included in the study for each individual patient, the hazard ratio for aortic aneurysm or dissection was 1.62 (1.05 to 2.48).

Discussion

Principal findings

In this nationwide, propensity score matched cohort study in Sweden, we investigated the association between use of oral fluoroquinolones and risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection, as compared with use of amoxicillin. Use of fluoroquinolones was associated with a 66% increased rate of aortic aneurysm or dissection within a 60 day risk period from start of treatment, which corresponded to an absolute difference of 82 cases per 1 million treatment episodes.

Comparison with other studies and interpretation of results

Applying a nationwide design, which ensured generalisability, and methods to attempt to limit the possibility of confounding, our study confirms and substantially expands on the two previous studies that have reported an increased risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection associated with fluoroquinolones. A cohort study among older adults in Ontario, Canada, reported an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.24 (95% confidence interval 2.02 to 2.49) for a risk period of about 37 days.12 However, that study adjusted for a limited number of covariates and might therefore not have fully accounted for potential confounding due to differences in baseline health status between patients receiving or not receiving fluoroquinolone. Furthermore, it compared fluoroquinolone use with no use of these antibiotics, an analytical design that could have introduced bias because of important unmeasured factors associated with filling an antibiotic prescription. Such factors include infection, which might influence the risk of aortic aneurysm and introduce confounding by indication, and diagnostic assessment (for example, radiological imaging), which might affect the probability of detection of an aneurysm. A nested case-control study from Taiwan used a 60 day risk period and found an adjusted rate ratio of 2.43 (95% confidence interval 1.83 to 3.22)11; likewise, this study did not have an active comparator and could have overestimated the risk.

Our findings suggest that the magnitude of the association between fluoroquinolones and aortic aneurysm, when assessed in a risk period longer than the common duration of a treatment course (usually 7-14 days), might not be as pronounced as indicated by these two previous studies. The studies both reported more than a twofold increase in risk (although confidence intervals between our and the other studies are overlapping). Our results also indicate that the association could be largely driven by aneurysm, and not dissection.

Furthermore, our study provides some degree of characterisation of the timing of this association, suggesting that the risk associated with fluoroquinolones might be most pronounced in the first 10 days after start of treatment; this would correspond to when treatment is ongoing. If the association is causal, these data indicate that a potential mechanism is relatively acute in onset, largely waning after treatment cessation. Consistent with this finding, the risk of Achilles tendon disorders is highest in the first 15-30 days following start of fluoroquinolone treatment.3 Lending some support to the possibility of a mechanism with acute onset, experimental studies in tendon cells have found that several matrix metalloproteinases, which are known to degrade critical components of the extracellular matrix, are promptly up regulated following exposure to ciprofloxacin.5 6 Although a mechanism implicating matrix metalloproteinases has been proposed to be involved in the association between fluoroquinolones and aortic aneurysm,11 and metalloproteinases are known to have a role in the pathophysiology of aortic aneurysm,9 10 future experimental work will have to determine how fluoroquinolones interact with the aorta.

Our study supports the notion that fluoroquinolone use could be associated with an increased risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection. Before these results are used to guide clinical decision making, the collective body of data on this safety issue should be scrutinised by drug regulatory authorities and weighed, together with other safety issues with this drug class, against the benefits of treatment; this will support appropriate clinical treatment recommendations.

Strengths and limitations

An important concern in any observational study is the possibility of confounding. We used an active comparator to limit confounding by factors associated with filling an antibiotic prescription, including confounding by indication, and propensity score matching derived from a range of covariates. Despite this, the possibility of residual confounding (for example, due to differences in smoking status or blood pressure levels between exposure groups) cannot completely be ruled out. Another study limitation, which is generic to database studies, was our reliance on filled prescriptions to define drug exposure; non-adherence to fluoroquinolones would bias results towards the null.

The possibility of protopathic bias cannot be excluded—whereby initial symptoms of aortic aneurysm are clinically interpreted as possible infection and lead to fluoroquinolone treatment, which would result in overestimation of risk. However, protopathic bias seems unlikely because infection is not a common first diagnosis in cases where aortic aneurysm is initially misdiagnosed. In a systematic review based on eight studies and 927 patients, among patients in whom ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm was initially misdiagnosed, the most common initial diagnoses were renal colic (6% of total patients), myocardial infarction (6%), colonic inflammation (3%), and gastrointestinal perforation (3%), whereas 12% did not receive an initial diagnosis.23 On a similar note, if an infection represented indication for treatment with fluroquinolones, but not amoxicillin, and later led to development of an infectious aneurysm, it would bias results towards increased risk.24 25 This possibility too appears unlikely to explain the observed results because infected aneurysms are rare, representing 0.5-2.5% of all aortic aneurysms, and because patients with infected aneurysm may present without a preceding infectious episode. Most treatment episodes with fluoroquinolones in our study were with ciprofloxacin and results are therefore mainly applicable to this specific fluoroquinolone. Additional studies are needed to investigate whether there are differences between individual fluoroquinolones with respect to the risk of aortic aneurysm. Further work is also needed to confirm that the association is driven by aortic aneurysm, and not dissection, as well as the timing of onset of aortic aneurysm suggested by our study.

What is already known on this topic

Recent studies have raised concern that fluoroquinolone antibiotics could be associated with an increased risk of aortic aneurysm

Fluoroquinolones have non-antimicrobial properties that might jeopardise the integrity of the extracellular matrix of the vascular wall

What this study adds

In this nationwide, propensity score matched cohort study in Sweden, there was a 66% increased rate of aortic aneurysm or dissection associated with oral fluoroquinolone use, compared with amoxicillin use, within a 60 day risk period from start of treatment

This result corresponded to an absolute difference of 82 cases of aortic aneurysm or dissection per 1 million treatment episodes; the association appeared to be largely driven by aortic aneurysm

Although the absolute risk increase was relatively small, it should be interpreted in the context of the widespread use of fluoroquinolones

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary material

Contributors: BP had full access to all the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors conceived and designed the study; acquired, analysed, and interpreted the data; and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. BP drafted the manuscript. HS carried out the statistical analysis. All authors obtained funding. BP and HS are the guarantors.

Funding: There was no specific funding for this study. BP is supported by an investigator grant from the Strategic Research Area Epidemiology programme at Karolinska Institutet. MI is supported by an investigator grant from the Swedish Government Funds for Clinical Research (ALF). HS is supported by an investigator grant from the Lundbeck Foundation. The funders had no role in in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Lund, Sweden (2013/717).

Data sharing: No additional data available. Statistical code available on request.

The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1. Hicks LA, Taylor TH, Jr, Hunkler RJUS. US outpatient antibiotic prescribing, 2010. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1461-2. 10.1056/NEJMc1212055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, et al. US outpatient antibiotic prescribing variation according to geography, patient population, and provider specialty in 2011. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:1308-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stephenson AL, Wu W, Cortes D, Rochon PA. Tendon injury and fluoroquinolone use: a systematic review. Drug Saf 2013;36:709-21. 10.1007/s40264-013-0089-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cipro (ciprofloxacin product information). Bayer HealthCare. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/019537s085,020780s042lbl.pdf.

- 5. Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chen CP, et al. Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res 2011;29:67-73. 10.1002/jor.21196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corps AN, Harrall RL, Curry VA, Fenwick SA, Hazleman BL, Riley GP. Ciprofloxacin enhances the stimulation of matrix metalloproteinase 3 expression by interleukin-1beta in human tendon-derived cells. A potential mechanism of fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:3034-40. 10.1002/art.10617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang HN, Pang JH, Chen CP, et al. The effect of aging on migration, proliferation, and collagen expression of tenocytes in response to ciprofloxacin. J Orthop Res 2012;30:764-8. 10.1002/jor.21576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pouzaud F, Bernard-Beaubois K, Thevenin M, Warnet JM, Hayem G, Rat P. In vitro discrimination of fluoroquinolones toxicity on tendon cells: involvement of oxidative stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004;308:394-402. 10.1124/jpet.103.057984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kent KC. Clinical practice. Abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2101-8. 10.1056/NEJMcp1401430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldfinger JZ, Halperin JL, Marin ML, Stewart AS, Eagle KA, Fuster V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:1725-39. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee CC, Lee MT, Chen YS, et al. Risk of aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm in patients taking oral fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1839-47. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daneman N, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e010077. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fluoroquinolones. Signal of aortic aneurysm and dissection. Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC). Minutes of PRAC meeting on 10-13 May 2016. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Minutes/2016/07/WC500209623.pdf.

- 14. Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months [correction in: Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008;17:533]. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:726-35. 10.1002/pds.1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Patient Register. National Board of Health and Welfare. www.socialstyrelsen.se/register/halsodataregister/patientregistret/inenglish.

- 16.Parson LS. Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques. Proceedings of the 26th Annual SAS Users Group International Conference, 2001. Paper 214-26. www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi26/p214-26.pdf.

- 17. Austin PC. Primer on statistical interpretation or methods report card on propensity-score matching in the cardiology literature from 2004 to 2006: a systematic review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2008;1:62-7. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.790634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. D’Agostino RB, Jr, Rubin DB. Estimating and using propensity scores with partially missing data. J Am Stat Assoc 2000;95:749-59 10.1080/01621459.2000.10474263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Landenhed M, Engström G, Gottsäter A, et al. Risk profiles for aortic dissection and ruptured or surgically treated aneurysms: a prospective cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e001513. 10.1161/JAHA.114.001513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sundbøll J, Adelborg K, Munch T, et al. Positive predictive value of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry: a validation study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012832. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Svanström H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of azithromycin and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1704-12. 10.1056/NEJMoa1300799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Azhar B, Patel SR, Holt PJ, Hinchliffe RJ, Thompson MM, Karthikesalingam A. Misdiagnosis of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endovasc Ther 2014;21:568-75. 10.1583/13-4626MR.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sörelius K, Mani K, Björck M, et al. European MAA collaborators Endovascular treatment of mycotic aortic aneurysms: a European multicenter study. Circulation 2014;130:2136-42. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laohapensang K, Rutherford RB, Arworn S. Infected aneurysm. Ann Vasc Dis 2010;3:16-23. 10.3400/avd.ctiia09002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary material