Highlights

-

•

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the main cause of morbidity and mortality in individuals with debilitating and life threatening affects.

-

•

Patients with major head injury must be monitored for signs and symptoms of endocrine dysfunction

-

•

Untreated TBI induced hypopituitarism contributes to the chronic neurobehavioral problems seen in many head-injured patients.

-

•

Damage to the hypothalamus or pituitary gland caused by TBI may impact the production of pituitary hormones and functions of the brain.

-

•

Understanding and recognizing pituitary dysfunction after TBI can lead to better outcomes and improved quality of life.

Keywords: Pituitary disorders, Endocrinology, Neurological injury, Neurology, Traumatic brain injury, Hypopituitarism

Abstract

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in young trauma patients with resultant multi-organ effects. Hypopituitarism following TBI can be debilitating and life threatening. TBI which causes hypopituitarism may be characterized by a single head injury, such as from a motor vehicle accident, or by chronic repetitive head trauma, as seen in combative supports including boxing, kick-boxing, and football. In the majority of cases, a diagnosis of hypopituitarism can be entirely missed resulting in severe neuro-endocrine dysfunction. We present a case series of two patients diagnosed with hypopituitarism after TBI and treated appropriately with favorable outcome.

Case presentations

The first case is a 34 year-old male, who presented to the emergency department with blunt head trauma after a motor vehicle accident while riding his bicycle. He suffered from severe cranio-facial injuries, resulting in multifocal hemorrhagic contusions, epidural hematoma, and extensive cranio-facial fractures involving the sinuses. The patient developed persistent hypotension with a blood pressure as low as 60/40 mmHg on hospital day three.

The second case is a 56 year-old male with a history of schizophrenia, who suffered traumatic brain injury after he was hit by a train. The patient sustained multiple facial fractures, pneumocephalus and C2/7 transverse processes fractures. He also had persistent hypotension, unresponsive to standard treatment. Investigation revealed a deficiency of anterior pituitary hormones resulting from pituitary axis disruption.

Discussion

Hypopituitarism is becoming an increasingly recognized complication following TBI, ranging from total to isolated deficiencies. Traumatic Brain Injury is a major public health problem and is one of the leading causes of disability. Understanding and recognizing pituitary dysfunction after TBI can lead to better outcomes and improved quality of life.

Conclusion

Patients with major head injury and, in particular, those with fractures of the base of the skull, must be closely monitored for signs and symptoms of endocrine dysfunction. Appropriate dynamic pituitary-function screening should be performed.

1. Background

Hypopituitarism is an insidious clinical manifestation, which can be extremely difficult to identify following a traumatic brain injury. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a cause of hypopituitarism in adults with growth hormone deficiency cited as one of the most frequent pituitary deficits [9]. Although most acute cases of post-traumatic neuroendocrine dysfunction seem to be transient, permanent mild deficiency of pituitary hormones can be overlooked in chronic cases, as patients might have mild symptoms and/or other significant neurological disabilities [3]. Pituitary insufficiency can complicate and delay the recovery process after TBI, impacting the outcome [5]. Deficiencies in individual hormones result in imbalance in normal physiological processes equipped to deal with the stress after TBI. Early recognition and prompt treatment of pituitary insufficiency can facilitate the overall rehabilitation after TBI resulting in favorable outcomes. This work has been reported in line with the PROCESS criteria [1].

CASE 1

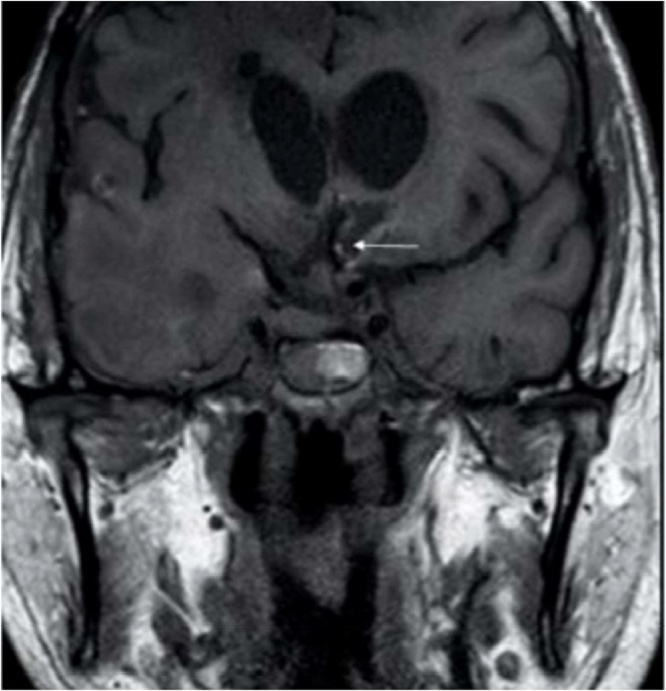

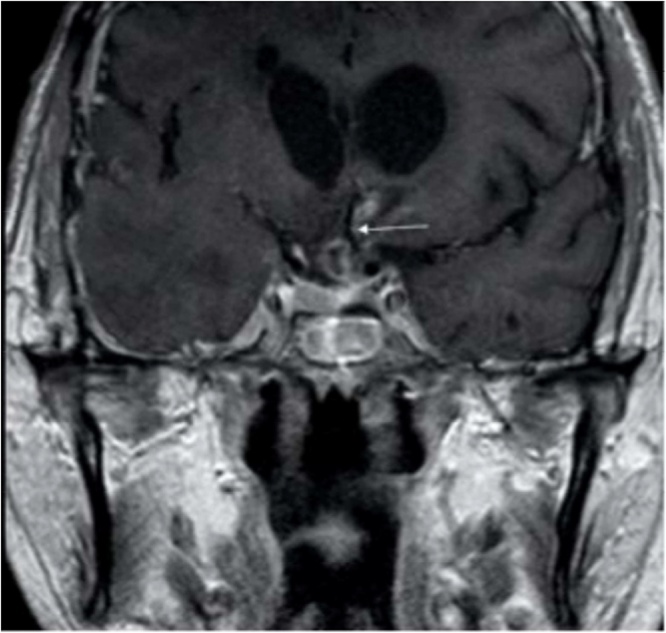

A 34 year-old male presented to the Emergency Department with blunt head trauma after a motor vehicle accident while riding his bicycle. He suffered from severe cranio-facial injuries resulting in multifocal hemorrhagic contusions, epidural hematoma, and extensive cranio-facial fractures involving the sinuses. The patient developed persistent hypotension with a blood pressure as low as 60/40 mmHg on hospital day three. He was resuscitated with crystalloids and vasopressors. Despite multiple vasopressors and fluid resuscitation, he remained hypotensive for the next two days. After basic investigations to determine the cause of his persistent hypotension were unremarkable, anterior pituitary hormonal levels were measured. Investigations demonstrated severe deficiency of anterior pituitary hormones. Post injury hormonal levels (normal range) were: cortisol 0.80 ug/dl (6.0–21.0), growth hormone (GH) 0.14 ng/ml (1–9), luteinizing hormone (LH) 0.12 U/L (1.50–9.3), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) 0.30 U/L (1.0-14.0), Free T4 0.48 ng/dl (0.9–1.9 ng/dl), free T3 1.0 ng/dl (2.18-3.98) and testosterone 11.37 ng/dl (300–900), while levels of thyrotropin (TSH) and adrenocorticotropic (ACTH) hormones were unchanged. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pituitary gland showed disruption of the pituitary stalk (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

CASE 2

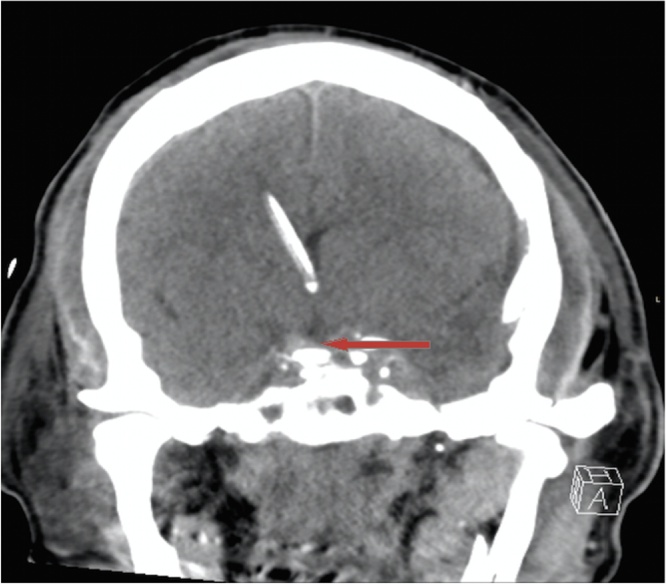

A 56 year-old male with a history of schizophrenia suffered traumatic brain injury after he was hit by a train. The patient sustained multiple facial fractures, pneumocephalus and C2/7 transverse processes fractures. He also had persistent hypotension with no response to standard treatment. Investigation revealed deficiency of anterior pituitary hormones resulting from pituitary axis disruption (Fig. 3). Levels of GH, Free T4, Insulin like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1), and Testosterone were found to be low post injury while levels for thyrotropin (TSH), (ACTH), (LH) and FSH hormones remain unchanged.

Fig. 1.

Coronal view of T1-weighted MRI of the Brain showing pituitary stalk disruption.

Fig. 2.

Coronal view of T1-weighted MRI of Brain showing pituitary stalk abnormality.

Fig. 3.

CT scan showing Pituitary stalk disruption.

Both patients were placed on hormonal replacement therapy with glucocorticoid and levothyroxine. Following hormonal therapy, significant improvements in blood pressure, concentration, memory, depression, anxiety and fatigue were observed. Patients were discharged to a skilled TBI facility.

2. Discussion

Hypopituitarism is becoming an increasingly recognized complication following TBI, ranging from total to isolated deficiencies. Traumatic Brain Injury is a major public health problem and is one of the leading causes of disability. There are 230,000 hospital admissions annually in the U.S. with an incidence of nearly 100 per 100,000. As of 1998, 1.5–2 million TBIs were reported annually with more than 50,000 resulting in death. Each year, 70,000 to 90,000 people develop a significant loss of brain function. The National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Panel on Rehabilitation of Persons with TBI estimated that 2.5–6.5 million people in the U.S. are living with TBI.

Damage to the hypothalamus or pituitary gland caused by TBI may impact the production of pituitary hormones and other neuroendocrine functions of the brain. Current data suggest that TBI may result in pituitary dysfunction in up to 20–50% of the cases [[8], [12]]. Pituitary hemorrhagic infarction (70%), and hypothalamic micro hemorrhages (40%) contribute to the pathogenesis of hypopituitarism. The infundibular hypothalamic pituitary structure is particularly fragile and secondary injury due to vascular compromise may be a common cause of post traumatic hypopituitarism [11].

Cyran [7] reported the first case of traumatic brain injury (TBI) induced hypopituitarism in 1918. The patient was a young adult male, who had experienced a severe form of head trauma and presented with endocrine abnormalities within months to years after the accident. Immediately after TBI, evaluation of pituitary function can be difficult due to hormonal alterations and effects of different critical care drugs used in the initial phase. Untreated TBI induced hypopituitarism contributes to the chronic neurobehavioral problems seen in many head-injured patients. Our patients had pituitary stalk lesions identified on scans in the immediate post traumatic period.

Bondanelli et al [6] noticed that patients who suffered from mild TBI had a 37.5% pituitary dysfunction in comparison to 59.3% in patients who suffered from severe TBI. Growth hormone deficiency (GHD) is the most common hormone deficiency in both severe and moderate TBI. Its prevalence varies from 2 to 66%, with 39% of cases having severe GHD. Prevalence of the other pituitary deficiencies is variable among the studies, ranging from 0 to 60% for secondary adrenal insufficiency, 0–29% for secondary hypothyroidism, 0–29% for central hypogonadism, and 0–48% for abnormal hypoprolactinemia [10].

Hypopituitarism can develop as a consequence of TBI. In acute cases, where the brain injury is severe, it is most often associated with disruption of pituitary axis [2]. Chronic hypopituitarism requiring hormonal replacement after TBI is directly related to the severity of brain injury with proportional increase in disability [4]. Following TBI the patients had abnormalities of pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction within one week. In comparison, among patients who showed sign of dysfunction in at least one of the pituitary-adrenal axis at four to six months following TBI, hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism was the most common. Our patients were diagnosed early and placed on hormonal replacement therapy, including glucocorticoids, with significant improvement. By recognizing signs of hypopituitarism early and urgently treating with hormone replacement therapy, especially glucocorticoids, we can prevent the development of neurocognitive dysfunction.

3. Conclusion

Patients with major head injury and, in particular those with fractures of the base of the skull, must be closely monitored for signs and symptoms of endocrine dysfunction. Vascular damage, hypoxic insult, direct trauma TBI-induced pituitary-dysfunction remains undiagnosed and therefore untreated in most patients because of the nonspecific and subtle clinical manifestations of hypopituitarism. The diagnosis and treatment of unrecognized hypopituitarism due to TBI are very important not only to decrease morbidity and mortality due to hypopituitarism but also to alleviate the chronic sequel caused by TBI. Appropriate dynamic pituitary-function screening should be performed. There is clinical relevance to brain injury–induced anterior pituitary dysfunction and appropriate hormonal replacement may provide notable improvement of symptoms related to the post-traumatic syndrome as well as enhance the recovery of these patients. The outcomes of hypopituitarism during the acute phase of TBI can be predicted but the outcomes in long-term effects remain unclear, warranting further investigation.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts.

Sources of funding

No source of funding.

Consent

Written informed consents were obtained from both patients for publication of this case report and accompanying images. Copies of the written consents are available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Khuram Khan- Abstract, Figure collections, writing, format.

Saqib Saeed- writing, others, reviewing.

Sanjiv Gray- others, writing, format.

Alexius Ramcharan-review, final writing, editing.

Registration of research studies

Case series

UIN for Research Registry

researchregistry3580

Guarantor

Khuram Khan

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Rammohan S., Barai I., Orgill D.P., PROCESS Group The PROCESS statement: preferred reporting of case series in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2016;36(Pt A):319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agha A., Rogers B., Mylotte D., Taleb F., Tormey W., Phillips J., Thompson C.J. Neuroendocrine dysfunction in the acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2004;60:584–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrawal A., Reddy P.A., Prasad N.R. Endocrine manifestations of traumatic brain injury. Ind. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;9(December (2)):123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bavisetty S., McArthur D.L., Dusick J.R. Chronic hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury: risk assessment and relationship to outcome. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1080–1094. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000325870.60129.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bondanelli M., Ambrosio M.R., Cavazzini L. Anterior pituitary function may predict functional and cognitive outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury undergoing rehabilitation. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24(November (11)):1687–1698. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bondanelli M., Ambrosio M.R., Zatelli M.C., De Marinis L., degli Uberti E.C. Hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2005;152(5):679–691. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cyran E. Hypophysenschadigung durch schadelbasisfraktur. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1918;44:1261. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giordano G., Aimaretti G., Ghigo E. Variations of pituitary function over time after brain injuries: the lesson from a prospective study. Pituitary. 2005;8:227–231. doi: 10.1007/s11102-006-6045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giuliano S., Talarico S., Bruno L. Growth hormone deficiency and hypopituitarism in adults after complicated mild traumatic brain injury. Endocrine. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly D.F., Gonzalo I.T., Cohan P., Berman N., Swerdloff R., Wang C. Hypopituitarism following traumatic brain injury and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a preliminary report. J. Neurosurg. 2000;93:743–752. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.5.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powner D.J., Boccalandro C., Serdar Alp M., Vollmer D.G. Endocrine failure after traumatic brain injury in adults. Neurocrit. Care. 2006;5(1):61–70. doi: 10.1385/ncc:5:1:61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanriverdi F., Senyurek H., Unluhizarci K., Selcuklu A., Casanueva F.F., Kelestimur F. High risk of hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury: a prospective investigation of anterior pituitary function in the acute phase and 12 months after trauma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:2105–2111. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]