Abstract

Background

The aim of palliative care is to improve the quality of life of patients and families through the prevention and relief of suffering. Frequently, patients may choose to receive palliative care in the home. The objective of this paper is to summarize the quality and primary outcomes measured within the palliative care in the home literature. This will synthesize the current state of the literature and inform future work.

Methods

A scoping review was completed using PRISMA guidelines. PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, EconLit, PsycINFO, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, and National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database were searched from inception to August 2016. Inclusion criteria included: 1) care was provided in the “home of the patient” as defined by the study, 2) outcomes were reported, and 3) reported original data. Thematic component analysis was completed to categorize interventions.

Results

Fifty-three studies formed the final data set. The literature varied extensively. Five themes were identified: accessibility of healthcare, caregiver support, individualized patient centered care, multidisciplinary care provision, and quality improvement. Primary outcomes were resource use, symptom burden, quality of life, satisfaction, caregiver distress, place of death, cost analysis, or described experiences. The majority of studies were of moderate or unclear quality.

Conclusions

There is robust literature of varying quality, assessing different components of palliative care in the home interventions, and measuring different outcomes. To be meaningful to patients, these interventions need to be consistently evaluated with outcomes that matter to patients. Future research could focus on reaching a consensus for outcomes to evaluate palliative care in the home interventions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12904-018-0299-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

By 2056, 480,000 Canadian deaths per year are predicted with 90% of those deaths being eligible for palliative care [1]. The aim of palliative care is to improve the quality of life of patients and families through the prevention and relief of suffering [2]. Frequently, patients may choose to receive palliative care in the home. Palliative care in the home is the provision of specialized palliative care in the patient’s home, most often provided by nurses and/or physicians with or without connection to a hospital or hospice [3]. Three factors have been identified as contributing to the decision to receive palliative care in the home: fulfilling a promise to provide care to the patient at home, the wish to maintain a ‘normal family life’, and previous negative experiences in institutional care settings [4].

In a recent survey of 1200 Canadians, greater than 70% of respondents preferred to be at home near death [5]. Palliative care in the home interventions vary widely, from interventions attempting to provide hope, to informal caregiver advising or after-hours night respite [6–8]. Frequently, palliative care is evaluated retrospectively through proxy reports and routine data collection [9]. Palliative care has also been evaluated in terms of cost and resource utilization [10]. Although location of death, at home or in hospital, has frequently been used as a metric to evaluate palliative care in the home, this measure is widely criticized as it accounts for only the conclusion to the process of dying [11].

Further, in 2013, a Cochrane review of home based palliative care for patients and their caregivers found positive effects on symptom burden, and no impact on caregiver grief, compared to usual care [10]. Another recent systematic review found that regular communication with medical professionals, spiritual needs, mobility assistance and financial support, information about illness progression, and respite options for caregivers were not adequately addressed by palliative care in the home [12].

The breadth of the body of literature examining palliative care in the home is unknown. Palliative care in the home interventions vary significantly in terms of the components of care, providers offering the interventions, and target recipients. The objective of this scoping review is to clarify the current state of the palliative care in the home literature in terms of study quality, primary outcomes measured, and begin to categorize palliative home care interventions. Summarizing the current literature will also assist future contributions to develop intervention evaluations that facilitate comparison and identify value for stakeholders.

Methods

Search strategy

A scoping review was completed [13]. Quality of included studies was assessed to increase the utility of this scoping review and to add the needed quality lens to the literature. In August 2016, the following electronic databases were searched from inception: PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, Cochrane Library, EconLit, PsycINFO, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, and National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database. Palliative care in the home experts were contacted to identify additional papers. Search results were limited to those published after the year 2000, to ensure that included studies were representative of modern palliative home care. Only published studies were reviewed thus ethics approval was not required. Grey literature was not included. Only English search results with human subjects were included in abstract review. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed to ensure methodological best practices [14].

The search strategy consisted of three concepts. First, terms for palliative care such as “palliative care,” “terminally ill,” and “end of life care” were searched. Second, terms for home care such as “home care services/trends,” “health system pathway,” and “component” were searched. Third, terms for outcomes such as “health care quality, access, and evaluation,” “quality,” and “patient satisfaction” were searched. These three concepts were combined using the Boolean operator “and.” The PubMed search strategy is included in Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were reviewed for eligibility in duplicate. Inclusion criteria were: 1) must assess at least one component of palliative care; 2) must report location of care as “home of patient” irrespective of if care was delivered in an individual home, hospice, or continuing care; 3) report on any outcome; and 4) report primary data. No study designs were excluded. Abstracts included by either reviewer proceeded to full text review. At full text review, a third reviewer was consulted to resolve inclusion disagreement.

Analysis

Included studies were classified by primary outcome. Data extracted, independently and verified by a second reviewer, included objective, methods, primary outcomes, and themes addressed. Study quality of randomized controlled trials was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (ROB) tool [15]. Controlled before and after studies was assessed using the same criteria as randomized controlled trials, but reported as high risk of bias on random sequence generation and allocation sequence concealment [16]. Quality of cohort studies was assessed with Newcastle-Ottawa criteria [17]. Quality of qualitative studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist, as recommended by Cochrane [18, 19]. Cross-sectional study quality was assessed using the Cochrane suggested “Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies” [20, 21]. Cost studies did not include outcomes in analysis, and were therefore not appropriate for any existing validated quality assessment tools.

Thematic component analysis was used to describe palliative home care interventions [22]. Face validity of intervention themes was established with expert opinion. The five themes categorizing palliative home care interventions were: accessibility of healthcare, family and caregiver support, individualized patient centered care, multidisciplinary care provision, and quality improvement.

Results

Study characteristics

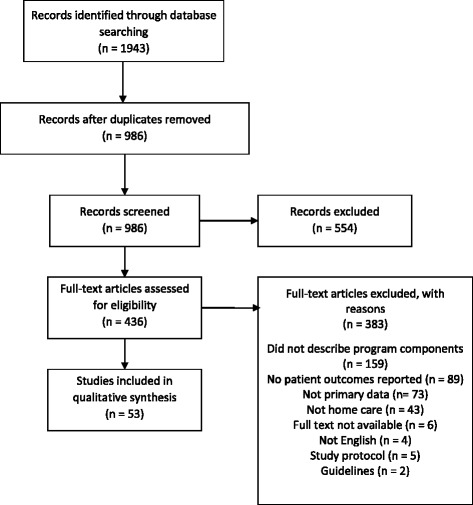

Searches of electronic databases returned 1993 records (Fig. 1). Following removal of duplicates, 986 records remained for title/abstract screening. Five hundred four articles were excluded at the title/abstract screening stage. The full text of 436 articles were assessed for inclusion, and 53 articles were included in the final data set (Fig. 1). Qualitative study designs were most numerous with 10 studies identified [8, 23–31]. This was followed by retrospective cohort study designs, with eight studies included [32–39]. The country in which the greatest number of studies was conducted was the United States, with 12 studies [32, 33, 40–49]. This was followed by Canada with nine studies [6, 30, 35, 37, 38, 50–53]. Included study characteristics are presented in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Quality

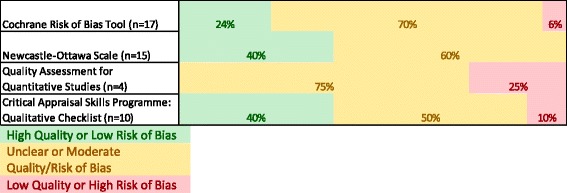

Included studies were assessed with the scales indicated in Fig. 2, and a category for overall quality was added. When using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (ROB) tool, categories assigned low risk of bias were given a value of one, categories assigned moderate risk of bias were given a value of two, and categories assessed as high risk of bias were given a value of three [15]. The sum of all ROB values was calculated. Values from 6 to 10 were categorized as low risk of bias or high quality, values from 11 to 14 were categorized as unclear/moderate quality, and values from 15 to 18 were categorized as low quality with the Cochrane ROB tool. When using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, from one to three stars was categorized as low quality, four to six stars was categorized as unclear/moderate quality, and seven to nine stars was categorized as high quality [17]. In qualitative studies assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist, the sum of the number of times “yes” was used as the answer to questions was calculated [18]. From one to three “yes” answers was categorized as low quality, four to six “yes” answers was categorized as unclear/moderate quality, and seven to nine “yes” answers was categorized as high quality.

Fig. 2.

Quality assessment of included studies

Most studies had an unclear risk of bias or quality (Fig. 2). The only study tool used that did not identify any studies with high quality was the quality assessment for quantitative studies tool.

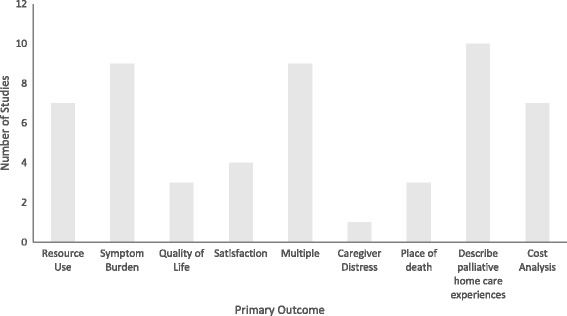

Outcomes identified

Multiple outcomes described studies in which the objective statement identified a combination of resource use, symptom burden, quality of life, satisfaction, caregiver distress, or place of death as the primary outcome (Fig. 3). The most commonly reported outcome was descriptive in nature with the objective of the study being to describe experiences with services offered.

Fig. 3.

Primary outcomes of included studies

Types of components

Intervention components were analyzed thematically, and five themes were identified (Table 1). Study interventions were described with one or more themes. Theme one described interventions in which a major component was an increase in the ability of participants to access healthcare as required. Theme two, caregiver support, was identified in 12 studies and reported effects on caregivers or provided services to caregivers. Theme three, individualized patient centered care, was identified in 35 studies. Individualized patient centered care described interventions in which tailored care to participant needs. Theme four, multidisciplinary care provision, was identified in 24 studies and described interventions with care provided by disciplines other than, or in addition to, physicians and nurses. To be categorized as addressing the theme of quality improvement, the publication had to describe the palliative care in the home intervention as a change to previously existing palliative care in the home service with the goal of improvement.

Table 1.

Overview of identified themes

| Theme | Description | Examples | Included Studies within Theme (n (%)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility of Healthcare | Interventions in which a major component was increased ability of study participants to access healthcare when required. | 24/7 on call care access Access to specialists | 27 (50.9) |

| Caregiver Support | Interventions in which effects for both patients and caregivers were reported, or services are also provided to caregivers. | Patient and caregiver education Advice for informal caregivers |

12 (22.6) |

| Individualized patient centered care | Interventions tailored to participant needs during delivery. | Care plan for symptom management Coordination of care |

35 (66.0) |

| Multidisciplinary care provision | Interventions provided by healthcare disciplines other than general practice physicians and nurses. | Social work involvement Physiotherapist involvement |

24 (45.3) |

| Quality improvement | Interventions described as changes to previously existing palliative care in the home services with the goal of improvement. | Tablet use for documentation Intervention standardization |

6 (11.3) |

Discussion

Fifty-three studies of various study designs, reporting on diverse outcomes and of varying quality were identified within the palliative home care literature. Of note, there are gaps in knowledge related to the outcome of caregiver distress, and the theme of quality improvement of palliative care in the home interventions. The extensive and heterogeneous nature of this body of literature limits our ability to make generalizations about effective palliative care in the home.

Palliative care in the home interventions were evaluated with the primary outcomes of resource use, cost, or place of death in nearly one third of included studies. Some have argued that these outcomes are not sufficient to assess the effectiveness of the intervention [54, 55]. The effectiveness measure should link to the objective of the intervention; place of death may be a less appropriate outcome than the location of care preceding death [55]. Our findings underscore the need to expand outcome measurement beyond routinely collected data to measure outcomes that are more tightly linked to the objective of palliative care in the home.

Included interventions differed in terms of providers delivering care and intervention components. The theme of individualized patient centered care was present in 66% of included studies and highlights the focus of these interventions on meeting patient needs. However, the diverse nature of these interventions makes generalizations about what components contributed to positive outcomes difficult. In addition, nine different primary outcomes were identified in the included studies. This diversity in outcomes makes it difficult to understand which components are effective or not. Consensus about which outcomes would be required to demonstrate that an intervention is effective would significantly advance the developing body of literature.

Although quality was mixed, all intervention evaluations reported positive outcomes. This supports the intuitive hypothesis that palliative care in the home is good for patients. However, this may be due to publication bias. Heterogeneity, in terms of intervention components and measurement of primary outcomes, inhibit our ability to assess whether studies with negative effects remain unpublished.

Similar to a meta-ethnography exploring patient and caregiver priorities for palliative care in the home, a focus on the increased availability of healthcare providers, symptom relief, and including caregivers as recipients and participants in care were prominent in intervention evaluations [56]. Like the findings of this study, a systematic review of systematic reviews of palliative care models also highlighted the diversity present in this body of literature, and the lack of consensus regarding outcome measurement [57].

There are limitations to our findings. The search strategy used was broad, however there is the possibility that appropriate studies may have been missed. To mitigate this risk, experts were contacted to identify additional literature. During our initial scoping work, the identified grey literature was reported in enough detail to contribute to this work without accompanying interviews to provide additional details. Thus, grey literature was excluded. This may have biased our results as the field is moving rapidly and novel interventions may not be reported in the published literature yet. Lastly, the interventions described in included studies are complex and multifaceted. This may have led to misclassification errors in the thematic analysis. However, we anticipate this error being small as it was done in duplicate and consensus was reached for each classification.

To move this field forward, future research should attempt to reach consensus on meaningful outcomes to be evaluated for palliative care in the home. Clinical events, costs, and place of death are routinely captured, but these may not match patient and caregiver priorities. Ideally, this consensus process would include key stakeholders representing all facets of palliative care at home: patients, caregivers, clinicians, and decision-makers.

Conclusions

There is variety in the quality of reporting, components of palliative care in the home interventions, and outcomes measured. To be meaningful to patients, these interventions need to be consistently evaluated with outcomes that matter to patients. Future research could focus on reaching a consensus for outcomes to evaluate palliative care in the home interventions.

Additional files

Appendix 1. PubMed search strategy. (DOCX 15 kb)

Table S1. Included study characteristics. (DOCX 48 kb)

Acknowledgements

The Health Technology Assessment Unit is supported by a financial contribution from Alberta Health (the ministry of health in the province of Alberta). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the official policy of Alberta Health.

Funding

No financial disclosures.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- CINAHL

Cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- ROB

Risk of bias

Authors’ contributions

FC lead all aspects of the work. MH, AM, LD, TM, ES, TM, TS, DM, and TN contributed to the design of the study and provided critical interpretation. MH, AM, LD, and LS completed the analysis. All authors contributed to and approved of the final manuscript. Fiona Clement (Corresponding Author) had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. She affirms that it is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a secondary analysis of published papers, therefore no ethics approval or consent to participate is required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12904-018-0299-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Mark Hofmeister, Email: mrhofmei@ucalgary.ca.

Ally Memedovich, Email: katherine.memedovich@ucalgary.ca.

Laura E. Dowsett, Email: lelegget@ucalgary.ca

Laura Sevick, Email: lsevick@ucalgary.ca.

Tamara McCarron, Email: tlmccarr@ucalgary.ca.

Eldon Spackman, Email: eldon.spackman@ucalgary.ca.

Tania Stafinski, Email: tanias@ualberta.ca.

Devidas Menon, Email: dev.menon@ualberta.ca.

Tom Noseworthy, Email: tnosewor@ucalgary.ca.

Fiona Clement, Phone: 403-210-9373, Email: fclement@ucalgary.ca.

References

- 1.Carstairs S. Raising the bar: a roadmap for the future of palliative Care in Canada. 2010. http://www.chpca.net/media/7859/Raising_the_Bar_June_2010.pdf. Accessed 7 Jul 2017.

- 2.Stone MJ. Goals of care at the end of life. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2001;14:134–137. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2001.11927748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordly M, Vadstrup ES, Sjøgren P, Kurita GP. Home-based specialized palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14:713–724. doi: 10.1017/S147895151600050X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stajduhar KI, Davies B. Variations in and factors influencing family members’ decisions for palliative home care. Palliat Med. 2005;19:21–32. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm963oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson DM, Cohen J, Deliens L, Hewitt JA, Houttekier D. The preferred place of last days: results of a representative population-based public survey. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:502–508. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duggleby WD, Degner L, Williams A, Wright K, Cooper D, Popkin D, et al. Living with hope: initial evaluation of a psychosocial hope intervention for older palliative home care patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh K, Jones L, Tookman A, Mason C, McLoughlin J, Blizard R, et al. Reducing emotional distress in people caring for patients receiving specialist palliative care. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:142–147. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristjanson LJ, Cousins K, White K, Andrews L, Lewin G, Tinnelly C, et al. Evaluation of a night respite community palliative care service. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2004;10:84–90 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Burt J. Back to basics: researching equity in palliative care. Palliat Med; 2012;26:5–6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(6). Art. No.: CD007760. 10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Billingham MJ, Billingham S-J. Congruence between preferred and actual place of death according to the presence of malignant or non-malignant disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3:144–154. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ventura AD, Burney S, Brooker J, Fletcher J, Ricciardelli L. Home-based palliative care: a systematic literature review of the self-reported unmet needs of patients and carers. Palliat Med. 2014;28:391–402. doi: 10.1177/0269216313511141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, TP G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan R, Hill S, Prictor M, McKenzie J. Study quality guide. 2013. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources. Accessed 4 Jul 2017.

- 17.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 4 Jul 2017.

- 18.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP qualitative research checklist. 2014. http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

- 19.Hannes K. Critical appraisal of qualitative research. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, et al., editors. Supplementary guidance for inclusion of ualitative research in cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. Version 1 (updated august 2011). Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group. http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance. Accessed 4 Jul 2017.

- 20.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. 2011. http://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed 4 Jul 2017.

- 21.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aoun S, Kristjanson LJ, Oldham L, Currow D. A qualitative investigation of the palliative care needs of terminally ill people who live alone. Collegian. 2008;15:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aoun S, O’Connor M, Skett K, Deas K, Smith J. Do models of care designed for terminally ill “home alone” people improve their end-of-life experience? A patient perspective: “home alone” models of care. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20:599–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appelin G, Brobäck G, Berterö C. A comprehensive picture of palliative care at home from the people involved. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005;9:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grande GE, Farquhar MC, Barclay SIG, Todd CJ. Valued aspects of primary palliative care: content analysis of bereaved carers’ descriptions. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:772–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jack BA, Baldry CR, Groves KE, Whelan A, Sephton J, Gaunt K. Supporting home care for the dying: an evaluation of healthcare professionals’ perspectives of an individually tailored hospice at home service. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:2778–2786. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jack BA, O’Brien MR, Scrutton J, Baldry CR, Groves KE. Supporting family carers providing end-of-life home care: a qualitative study on the impact of a hospice at home service. J Clin Nurs. 2014;24:131–140. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linderholm M, Friedrichsen M. A desire to be seen: family caregivers’ experiences of their caring role in palliative home care. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:28–36. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181af4f61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall D, Howell D, Brazil K, Howard M, Taniguchi A. Enhancing family physician capacity to deliver quality palliative home care. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:e1–e7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer Y, Bachner YG, Shvartzman P, Carmel S. Home death—the caregivers’ experiences. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;30:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arland LC, Hendricks-Ferguson VL, Pearson J, Foreman NK, Madden JR. Development of an in-home standardized end-of-life treatment program for pediatric patients dying of brain tumors: development of an in-home standardized end-of-life treatment program for pediatric patients dying of brain tumors. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2013;18:144–157. doi: 10.1111/jspn.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen CY, Thorsteinsdottir B, Cha SS, Hanson GJ, Peterson SM, Rahman PA, et al. Health care outcomes and advance care planning in older adults who receive home-based palliative care: a pilot cohort study. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:38–44. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Currow D, Agar M, Smith J, Abernethy A. Does palliative home oxygen improve dyspnoea? A consecutive cohort study. Palliat Med. 2009;23:309–316. doi: 10.1177/0269216309104058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maida V. Factors that promote success in home Paliative care: a study of a large suburban palliative care practice. J Palliat Care. 2002;18:282–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riolfi M, Buja A, Zanardo C, Marangon CF, Manno P, Baldo V. Effectiveness of palliative home-care services in reducing hospital admissions and determinants of hospitalization for terminally ill patients followed up by a palliative home-care team: a retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2013;28:403–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Seow H, Barbera L, Howell D, Dy SM. Did Ontario’s end-of-life care strategy reduce acute care service use? The need to use quality indicators for improvement. Healthc Q. 2010;13:93–100. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2013.21620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seow H, Barbera L, Howell D, Dy SM. Using more end-of-life homecare services is associated with using fewer acute care services: a population-based cohort study. Med Care. 2010;48:118–124. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c162ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan WS, Lee A, Yang SY, Chan S, Wu HY, Ng CWL, et al. Integrating palliative care across settings: a retrospective cohort study of a hospice home care programme for cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2016;30:634–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, Seitz R, Morgenstern N, Saito S, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care: RANDOMIZED IN-HOME PALLIATIVE CARE TRIAL. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:715–724. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doolittle GC. A cost measurement study for a home-based telehospice service. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6(suppl 1):193–195. doi: 10.1258/1357633001934645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edes TE, Lindbloom EJ, Deal JL, Madsen RW. Improving Care at Lower Cost for end-stage heart and lung disease: integrating end of life planning with home care. Univ Mo Fam Community Med. 2006;103:146–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enguidanos SM, Cherin D, Brumley R. Home-based palliative care study: site of death, and costs of medical Care for Patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2005;1:37–56. doi: 10.1300/J457v01n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandes R, Braun KL, Ozawa J, Compton M, Guzman C, Somogyi-Zalud E. Home-based palliative care services for underserved populations. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:413–419. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerr CW, Tangeman JC, Rudra CB, Grant PC, Luczkiewicz DL, Mylotte KM, et al. Clinical impact of a home-based palliative care program: a hospice-private payer partnership. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48:883–892. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lukas L, Foltz C, Paxton H. Hospital outcomes for a home-based palliative medicine consulting service. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:179–184. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McMillan S, Small BJ. Using the COPE intervention for family caregivers to improve symptoms of hospice Homeare patients: a clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:313–321. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ornstein K, Wajnberg A, Kaye-Kauderer H, Winkel G, DeCherrie L, Zhang M, et al. Reduction in symptoms for homebound patients receiving home-based primary and palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:1048–1054. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brink P, Partanen L. Emergency department use among end-of-life home care clients. J Palliat Care. 2011;27:224–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guerriere DN, Zagorski B, Coyte PC. Family caregiver satisfaction with home-based nursing and physician care over the palliative care trajectory: results from a longitudinal survey questionnaire. Palliat Med. 2013;27:632–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Klinger CA, Howell D, Marshall D, Zakus D, Brazil K, Deber RB. Resource utilization and cost analyses of home-based palliative care service provision: the Niagara west end-of-life shared-care project. Palliat Med. 2011;27:115–122. doi: 10.1177/0269216311433475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paré G, Sicotte C, Chekli M, Jaana M, Blois CD, Bouchard M. A pre-post evaluation of a telehomecare program in oncology and palliative care. Telemed E-Health. 2009;15:154–159. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCaffrey N, Cassel JB, Coast J. An economic view on the current state of the economics of palliative and end-of-life care. Palliat Med. 2017;31:291–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.O’Leary MJ, O’Brien AC, Murphy M, Crowley CM, Leahy HM, McCarthy JM, et al. Place of care: from referral to specialist palliative care until death. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7:53–59. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sarmento VP, Gysels M, Higginson IJ, Gomes B. Home palliative care works: but how? A meta-ethnography of the experiences of patients and family caregivers. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;0:1–14. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brereton L, Clark J, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, Preston L, Ryan T, et al. What do we know about different models of providing palliative care? Findings from a systematic review of reviews. Palliat Med. 2017;31:781–797. doi: 10.1177/0269216317701890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. PubMed search strategy. (DOCX 15 kb)

Table S1. Included study characteristics. (DOCX 48 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.