Abstract

Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) is a receptor tyrosine kinase that mediates growth, proliferation and survival. Dysregulation of IGF pathway contributes to initiation, progression and metastasis of cancer and is also involved in diseases of glucose metabolism, such as Diabetes. We have identified Ubiquilin1 (UBQLN1) as a novel interaction partner of IGF1R, IGF2R and Insulin Receptor. UBQLN family of proteins have been studied primarily in the context of protein quality control and in the field of neurodegenerative disorders. Our laboratory discovered a link between UBQLN1 function and tumorigenesis, such that UBQLN1 is lost and under-expressed in 50% of human lung adenocarcinoma cases. We demonstrate here that UBQLN1 regulates expression and activity of IGF1R. Following loss of UBQLN1 in lung adenocarcinoma cells, there is accelerated loss of IGF1R. Despite decreased levels of total receptors, the ratio of active:total receptors is higher in cells that lack UBQLN1. UBQLN1 also regulates Insulin Receptor (INSR) and IGF2R post-stimulation with ligand. We conclude that UBQLN1 is essential for normal regulation of IGF receptors. UBQLN1 deficient cells demonstrate increased cell viability compared to control when serum starved and stimulation of IGF pathway in these cells increased their migratory potential by 3-fold. As the IGF pathway is involved in processes of normal growth, development, metabolism and cancer progression, understanding its regulation by Ubiquilin1 can be of tremendous value to many disciplines.

Keywords: UBQLN, Ubiquilin, Insulin-like Growth Factor Receptor, IGF1R, IGF2R, Insulin Receptor, INSR, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase

INTRODUCTION

IGF1R (Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Receptor) is a receptor tyrosine kinase ubiquitously expressed on cell surfaces of all tissues. Ligand stimulation causes the receptor to transmit signals for cell proliferation, differentiation, survival and cellular metabolism. IGF receptors exist in the plasma membrane as preformed dimers. Known ligands of IGF1R are IGF-1 (highest affinity), IGF-2 and insulin. Activation of IGF pathway activates downstream PI3-AKT and RAS-MAPK pathways among others. IGF binding proteins 1–6 (IGFBPs) bind IGF receptor ligands and limit their bioavailability and binding to IGF1R (1,2).

Acromegaly or gigantism, an endocrinopathy resulting from high circulating levels of IGF1 is associated with three times increased risk of developing colorectal cancer (3). In a contrasting condition called Laron dwarfism, patients have low (1–10%) circulating IGF1 levels and are resistant to developing cancer and diabetes (4). The IGF1R gene does not harbor activating mutations like other receptor tyrosine kinases (EGFR and FGFR) and ligand independent activation of IGF1R is not known. Still, overexpression of IGF1R is a hallmark finding in lung cancer, malignant melanoma, primary breast cancer and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (5). This implies that alterations in expression and activity of IGF1R occur post translationally such as anomalous mechanisms of autocrine and paracrine stimulation of receptor, hybrid assemblies of IGF receptors, abnormalities in epigenetic and transcriptional control and in other proteins that regulate its trafficking and turnover (6). For example, mutations in c-Cbl, an E3 ligase, can dysregulate turnover of c-MET, a receptor tyrosine kinase, leading to persistent signaling even in the absence of receptor overexpression or activating oncogenic mutations (7). Currently, the IGF1/IGF1R axis is a major target of research for cancer therapy. IGF1R over expression is associated with an increased risk of recurrence of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (8). Additionally, high levels of circulating IGF1 is linked to an increased risk of development of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers (5,9). However, several pharmacological agents, monoclonal antibodies and small molecule inhibitors targeting this axis have failed to show significant benefit on overall survival (10). Unfortunately, expression of IGF1R does not always correlate with its cell surface expression and therefore it can be misleading to correlate its expression with expected response to therapy. This highlights the role of cellular and extracellular factors that modulate the activity of IGF1R directly or indirectly.

We have identified UBQLN1 as one such regulator of IGF1R expression and activity. The Ubiquilin family of proteins (UBQLN1–4, UBQLNL) are evolutionarily conserved structurally similar to each other. UBQLN1 is approximately a 63 kDa protein and has 3 main domains: ubiquitin-like domain (UBL) at the N-terminus, ubiquitin-associated domain (UBA) at the C-terminus and STI-1 chaperone-like regions in the middle (Figure 1A). UBQLN1 interacts with IGF1R and its UBA domain is required to stabilize IGF1R expression (2). UBQLN1 is lost and under-expressed in 50% of lung adenocarcinomas and loss of either UBQLN1 or UBQLN2 promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (11). Additionally, UBQLN1 is known to regulate other cell surface receptors like Presenilins (12), GABAA receptors (13,14) and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (15). Here, we demonstrate that UBQLN1 interacts with IGF1R, IGF2R and INSR and is essential for normal expression and activity of IGF1R in lung adenocarcinoma cells.

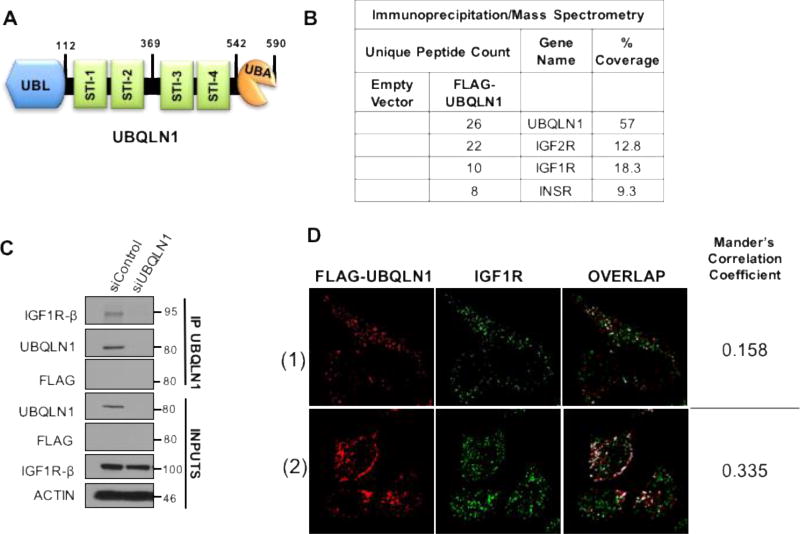

FIGURE 1. UBQLN1 interacts with IGF1R, IGF2R and INSR.

(A) Schematic of Ubiquilin1 protein. UBQLN1 is a 590 amino acid protein with an N-terminal UBL (ubiquitin-like) domain, four STI chaperone like domains in the middle and a C-terminal UBA (ubiquitin-associated) domain. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged UBQLN1 followed by co-immunoprecipitation (IP) by anti-FLAG antibody and mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. IGF1R, IGF2R and INSR were identified as some of the top interacting partners of FLAG-UBQLN1. (C) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with siRNA for UBQLN1 knock down (siUBQLN1) followed by co-immunoprecipitation by anti-UBQLN1 antibody and Western Blot analysis. (D) Confocal microscopy images of indirect immunofluorescence staining for FLAG-UBQLN1 (red) and IGF1R (green) in HeLa cells. Co-localization was determined for using JACop plugin of ImageJ software. Automatic threshold for images were determined by the Costes method and overlap coefficients (Mander’s Correlation Coefficients) were calculated. For the 2 chosen fields, 15.8–33.5% of FLAG-UBQLN1 overlaps with IGF1R.

EXPERIMENTAL

Cell culture

Human non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma cell lines A549 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) and cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 1% antibiotics/antimycotics (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The 3 cell lines were routinely sub-cultured every 3–4 days. All siRNA transfections were performed using Dharmafect1 #T-2001-03 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) as per manufacturer’s protocol. After total 48 hours of transfection, cells were serum starved for 12 hours. After which IGF1 (50ng/ml) was added to stimulate the cells. For protein stability studies, Cycloheximide (20uM), and for testing degradation pathways, Monensin (10uM) were added an hour prior to stimulating with IGF1. At the end of stimulation for various time points, cells were harvested in CHAPS lysis buffer (1% CHAPS detergent, 150mM NaCl, 50mM Tris pH 7, 5mM EDTA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein was quantified by using Pierce's BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (#23227) from Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA as per manufacturer’s protocol.

Plasmid Constructs

FLAG-UBQLN1 plasmid has been described previously. Constructs with deleted domains of UBQLN1 (Fig. 2), were developed using Q5 Site-Directed mutagenesis kit (New England Biolabs) and confirmed by sequencing.

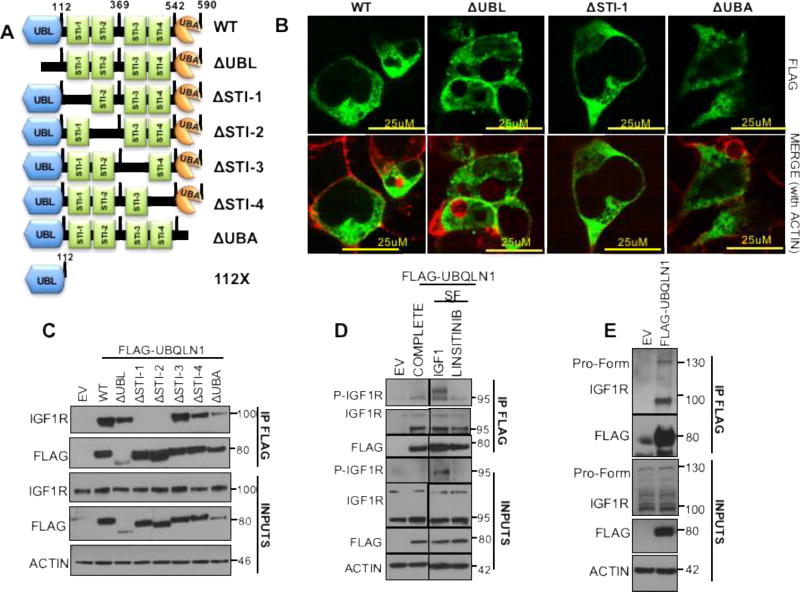

FIGURE 2. First two STI-1 domains of UBQLN1 are responsible for interaction with IGF1R.

(A) Schematic of UBQLN1WT and engineered FLAG-tagged domain deletion constructs missing individual domains. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-UBQLN1ΔUBL, FLAG-UBQLN1ΔSTI-1 and FLAG-UBQLN1ΔUBA constructs followed by indirect immunofluorescence staining for FLAG-UBQLN1. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged constructs of UBQLN1 (in A) followed by co-immunoprecipitation by anti-FLAG antibody and Western Blot analysis. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with empty vector or FLAG-UBQLN1 and cells were cultured in complete media (COMPLETE) or serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 (SF, IGF1) or Linsitinib (SF, LINSITINIB), a small molecule inhibitor of IGF1R activity, followed by co-immunoprecipitation by anti-FLAG antibody and Western Blot analysis (IGF1:50ng/ml, Linsitinib:1uM). (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with empty vector or FLAG-UBQLN1 showed that FLAG-UBQLN1 interacts with both immature pro-form of IGF1R at 135kD and mature, processed IGF1R at 100kD.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis

293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. DNA transfections were done using PEI (PEI 2.5:1 DNA). All cell extracts were prepared following scrape harvesting of 293T cells using CHAPS lysis buffer (1% CHAPS detergent, 150mM NaCl, 50mM Tris pH 7, 5mM EDTA), For immunoprecipitation, 400ug of protein was incubated in 400uL of total CHAPS buffer and incubated with indicated affinity matrix (Anti-FLAG beads) for 1 h at 4 °C. Following incubation, the matrix was washed three times in CHAPS buffer and then SDS loading buffer was added directly to washed matrix, boiled, and loaded directly into the wells of a PAGE gel.

Immunofluorescence

HEK 293T or HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-UBQLN1, dry seeded on round coverslips in 12 well plates and 48 hours post transfection were fixed with 4.0% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15–20 min and then permeabilized with 0.1% Saponin for 60 minutes at room temperature. Cells were rinsed thrice with PBS, and then incubated overnight with anti-UBQLN1 antibody (CST#1:1000). Next day, after three successive washes with PBS, cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:300, A11034 Molecular Probes, Invitrogen detection technologies, Eugene, OR, USA). After incubation with secondary antibody for 60 minutes, cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 Phalloidin (1:1000 A12380: Life technologies Eugene, OR, USA) for 10 minutes. After 3 successive washes with PBS, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1:000) for 10 min at room temperature followed by three washes (5–10 min each) with PBS. The cells were then imaged under Nikon A1R confocal laser scanning microscope. Multiple images were acquired from multiple experiments and representative images are presented.

Cell Viability Assay

A549 cells expressing UBQLN1 shRNA (shUBQLN1, shUBQLN2 and control) (2 × 104 cells) were seeded onto 96 well plate and cultured for 4 days under 3 different conditions-- serum-free media, serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 (50ng/ml) or serum-free media supplemented with Linsitinib (1uM) and IGF1 (50ng/ml). Relative cell viability was assessed by Alamar Blue assays on each day. Data were normalized to control shRNA cells in serum-free condition for each day. These experiments were performed 2 separate times and data here are represented as mean and standard error of mean of a one experiment performed in triplicates.

Transwell Migration

A549 cells expressing UBQLN1 shRNA (shUBQLN1, shUBQLN2 and control) (2.5 × 104 cells) were seeded onto wells of Transwell filters in a 12-well plate, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Corning). The Transwell setup consisted of an upper chamber (conditions of serum-free media, serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 (50ng/ml) or serum-free media supplemented with Linsitinib (1uM) and IGF1 (50ng/ml)) that was placed onto a lower chamber (RPMI media enhanced with 10% FBS, creating a chemotactic gradient). The upper chamber contained a microporous membrane allowing passage of cells that migrate towards serum. After incubation at 37C and 5% CO2 for 24 hours, the inserts were examined for migration in the above 3 conditions. Results were compiled as the mean and standard error of 3 separate experiments.

Total RNA Extraction and Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the A549 cells after washing twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and harvested with E.Z.N.A Total RNA Extraction Kit (Omega, USA) according to the supplier’s protocol followed by DNAse digestion. RNA quality and quantity were determined by photometry. Total RNA (1µg) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using Thermo Script RT–PCR kit. Briefly, RNA was reverse-transcribed in cDNA with oligo (dT) primers and 200 U of Superscript II (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time analysis for IGF1R, INSR, IGF1, IGF2, Insulin and normalizing gene human β2Microglobulin or β-Actin was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix as per the manufacturer’s instruction (Applied Biosytems). This technique continuously monitors the cycle-by-cycle accumulation of fluorescently labeled PCR product. Briefly, cDNA corresponding to 25 ng of RNA served as a template in a 10µl reaction mixture containing, 0.2 nM (each) primer, and 5µl FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green mix (ABI). Samples were loaded into 96-well plate format and incubated in the fluorescence thermocycler 7500 (ABI System). Initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min was followed by 45 cycles, each cycle consisting of 95 °C for 15 seconds, touchdown of 1 °C/cycle from the primer-specific start to end annealing temperatures for 5 seconds, and 60 °C for 10 seconds. The primer sequences used for specific genes are listed below. All quantifications were normalized to the housekeeping HPRT gene, which showed a very stable expression in A549 cells. Fold changes in gene expression were calculated using 2−ΔΔCT method. Following are the primer sequences used for the reaction:

-

IGF1R

F: GCCAAGCTAAACCGGCTAA

R: TATCCTCTTTTGGCCTGGACATA

-

IGF1

F: GATGCACACCATGTCCTCCT

R: AAAAGCCCCTGTCTCCACAC

-

IGF2

F: AGTTCTTCCAATATGACACCTGGAA

R: TGAACGCCTCGAGCTCCTT

-

hB2M

F: TGACTTTGTCACAGCCCAAGATA

R: AATGCGGCATCTTCAAACCT

-

ACTIN

F: TTGGCAATGAGCGGTTCC

R: GGTAGTTTCGTGGATGCCCAC

Antibodies

IGF1R-beta (CST#3027), IGF1R Beta XP (CST#9750), p-IGF1R beta (CST#3918), INSR (CST#3025), IGF2R (CST#14364), AKT (CST#9272), p-AKT (CST#9271); Tubulin #B512 (Sigma); GAPDH (SantaCruz#FL335); Actin (Sigma#A5316), Ubiquilin1 (CST#14526); Anti-FLAG Affinity Gel (Sigma#A2220), INSR (CST#3025), FLAG polyclonal (Sigma# F7425).

RNAi Sequences

All RNAi (siRNAs) used for study were ordered from Thermo Fisher Scientific Biosciences Inc. Lafayette, CO 80026, USA and transfections were done using Dharmafect1 as per the supplier’s instructions.

-

Non-Targeting Control

UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUACAA

-

UBQLN1

#1: GAAGAAAUCUCUAAACGUUUUUU

#2: GUACUACUGCGCCAAAUUUUU

RESULTS

UBQLN1 interacts with IGF1R, IGF2R, and INSR

We have previously shown that UBQLN1 interacts with IGF1R and UBQLN1’s UBA domain is required to protect IGF1R from MG132 (proteasomal inhibitor) mediated degradation (2). Here, we show Immunoprecipitation/Mass Spectrometry data for interaction of FLAG-UBQLN1 with IGF1R, IGF2R and INSR (Figure 1B). Next, we confirmed endogenous interaction between UBQLN1 and IGF1R by performing Immunoprecipitation/Western Blot analysis with anti-UBQLN1 antibody in HEK293T cells with control and siRNA mediated UBQLN1 knock down (Figure 1C). Additionally, we determined co-localization between these two proteins by overexpressing FLAG-UBQLN1 in HEK293T cells followed by immunofluorescence staining for FLAG-UBQLN1 and IGF1R (Figure 1D). After adjusting for image saturation by JACop plugin of ImageJ software analysis, we calculated overlap between these 2 proteins by Costes method represented as Mander’s correlation coefficients. We found that 15.8–33.5% of FLAG-UBQLN1 overlapped with endogenous IGF1R in the 2 fields shown. These immunofluorescence data imply that a fraction of total UBQLN1 associates with IGF1 receptors. These data confirm our previously published findings that UBQLN1 interacts with multiple substrates and participates in a variety of cellular processes (2).

To map the interaction between UBQLN1 and IGF1R, we used a series of domain deletion constructs (Figure 2A) described previously (2). First, we examined cellular distribution of these overexpressed constructs (FLAG-UBQLN1WT, UBQLN1ΔUBL, UBQLN1ΔSTI-1 and UBQLN1ΔUBA) in HEK293T cells by indirect immunofluorescence (Figure 2B). UBQLN1WT and domain deletion constructs showed uniform distribution in the cytoplasm while being distinctly absent from nuclei and vacuoles. Next, we performed immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody followed with Western Blot analysis for IGF1R. We found that STI-1 and STI-2 domains of UBQLN1 are crucial for interaction with IGF1R (Figure 2C). To characterize underlying conditions of association between these proteins, we performed additional Immunoprecipitaion/Western Blot studies in HEK293T cells overexpressing FLAG-UBQLN1. We detected an interaction between FLAG-UBQLN1 and phosphorylated IGF1R (Figure 2D), when the receptor is stimulated with exogenous IGF1, which disappears when phosphorylation is inhibited with Linsitinib treatment (a specific small molecule inhibitor of IGF1R activity). UBQLN1 also interacts with non-phosphorylated IGF1R as observed in all culture conditions: complete media, serum-free media, serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 and when treated with Linsitinib (Figure 2D). Additionally, UBQLN1 interacts with the larger, immature pro-form of IGF1R detected at 135 kD (Figure 2E) which indicates that UBQLN1 interacts with IGF1R during its translation or immediately after.

Based on our interaction data, we conclude that UBQLN1’s association with IGF1R is independent of IGF1R’s phosphorylation status and it appears that UBQLN1 is recruited to the receptor from the time of its synthesis.

UBQLN1 regulates expression and activity of IGF1R in lung adenocarcinoma cells

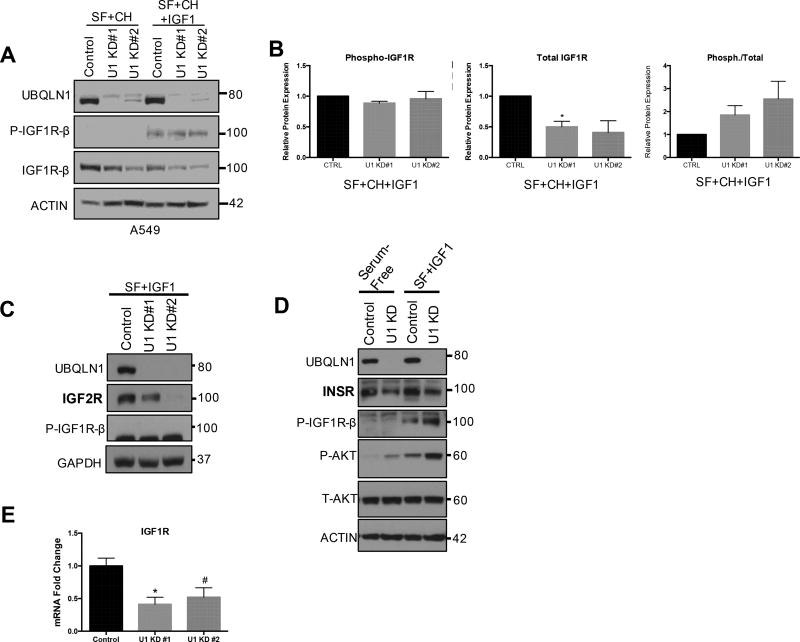

Following confirmation of interaction, we investigated effects of loss of UBQLN1 on expression of IGF1R in A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells. UBQLN1 expression was downregulated using two different siRNAs (U1 KD#1 and U1 KD#2). These cells were cultured in 2 different conditions: serum-free media (12 hours) and serum-free media (12 hours) supplemented with IGF1 (6 hours). Cells were incubated with a translational inhibitor, Cycloheximide for an hour before adding IGF1 to block de novo protein synthesis. This allowed us to assess the expression of IGF1R 6 hours post-stimulation. Cells were harvested, lysed and analyzed by Western Blot for total and phosphorylated IGF1R expression levels. UBQLN1 deficient cells showed decreased expression of total IGF1R in both conditions (Figure 3A) and the effect was more pronounced post-stimulation with IGF1. To ensure this phenotype was not specific to siRNA mediated decrease of UBQLN1, we confirmed these findings in CRISPR/Cas9 mediated UBQLN1 knock-out A549 cells and A549 cells stably expressing shRNA against UBQLN1 (Figure S1). Phosphorylated IGF1R levels were undetectable in serum-free media, however, post-stimulation with IGF1, the ratio of phosphorylated to total IGF1R levels was greatly increased in UBQLN1 deficient cells (~2 fold) compared to control (Figure 3B). Similarly, loss of UBQLN1 also caused decreased expression of IGF2R (Figure 3C) and INSR (Figure 3D) in A549 cells. Upon investigating IGF1R transcript levels, we found a 2-fold decrease in IGF1R mRNA expression (Figure 3E) (p=0.0015, SEM=0.04 for U1 KD#1, p=0.0094, SEM=0.06 for U1 KD#2).

FIGURE 3. UBQLN1 regulates expression and activity of IGF1R.

(A) Expression and activity of IGF1R were tested in A549 lung cancer cells following downregulation of UBQLN1 with two different siRNA (U1 KD#1 and U1 KD#2). Cells were serum starved (SF) overnight (12 hours), incubated with protein synthesis inhibitor Cycloheximide one hour prior to supplementing serum-free media with IGF1. 6 hours later, cells were harvested analyzed by Western Blot. (B) Data are normalized to Actin in non-targeting siRNA control in unstimulated cells and represented as mean+/−SEM from 2 experiments. *p ≤ 0.05. Expression of IGF2R (C) and INSR (D) were tested in A549 lung cancer cells following downregulation of UBQLN1 with two different siRNA (U1 KD#1 and U1 KD#2). Cells were cultured as in (A). IGF2R and INSR expression decreases post IGF1 stimulation in UBQLN1 deficient cells. Expression of P-AKT (D) is increased in UBQLN1 deficient cells under serum-free and stimulated conditions while T-AKT expression remains unchanged compared to control. Data are normalized to Actin in non-targeting siRNA control in unstimulated cells. (E) There is a 2-fold decrease in IGF1R mRNA expression in A549 cells that have siRNA mediated loss of UBQLN1 (p=0.0015, SEM=0.04 for U1 KD#1, p=0.0094, SEM=0.06 for U1 KD#2). Data are represented as represented as mean+/−SEM from 3 independent quantitative real-time PCR experiments done in triplicates.

Based on these data, we conclude that UBQLN1 deficient A549 cells not only have decreased synthesis of IGF1R, but also accelerated loss of the receptor when stimulated. However, despite decreased expression of total IGF1R, activity of the receptor is not decreased.

Loss of UBQLN1 accelerates loss of IGF1R

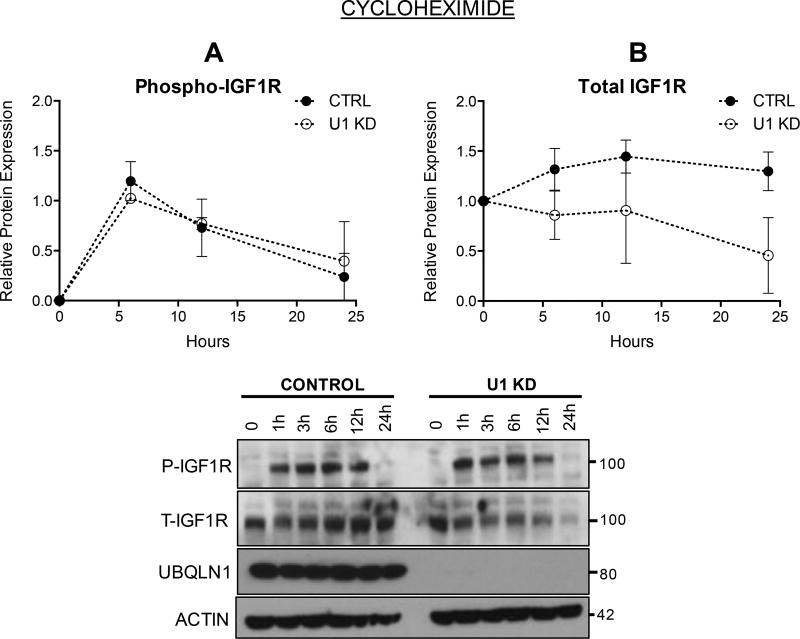

To investigate loss of IGF1R in the absence of UBQLN1, A549 cells stably expressing shRNA against UBQLN1 and control were treated with Cycloheximide (translational inhibitor) and expression and activity of IGF1R were tracked for up to 24 hours following stimulation with IGF1 (Figure 4). Overall, there were no differences in phosphorylation pattern of IGF1R (Figure 4A) between control and UBQLN1 deficient cells. However, expression of total IGF1R declined sharply in UBQLN1 deficient cells (Figure 4B) with almost all IGF1R disappeared by 24 hours.

FIGURE 4. Loss of UBQLN1 accelerates loss of IGF1R.

A549 cells expressing shRNA against UBQLN1 and non-targeting control were serum starved for 12 hours, followed by incubation with Cycloheximide (20uM), an inhibitor of de novo protein synthesis to study loss of IGF1R expression in UBQLN1 deficient cells, post-stimulation with IGF1. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points and Western Blot analysis for phosphorylated (A) and total receptor (B) levels were performed and graphed. Data are normalized to Actin in non-targeting shRNA control in unstimulated cells and represented as mean+/−SEM from 2 experiments.

Cycloheximide causes arrest of translational machinery thus preventing all new protein synthesis resulting from transcription. Therefore, it is likely that the increase in IGF1R expression observed in control cells is not due to increase in transcription but due to stimulation of Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) and Golgi processing of pre-formed, already translated monomers to its mature dimerized form. UBQLN1 plays a role in stabilizing and assembling newly translated GABAA receptors in the ER (14) and we hypothesize that it may do the same with IGF1R. Thus, it is possible that UBQLN1 deficient cells cannot replenish lost IGF1R like control cells do.

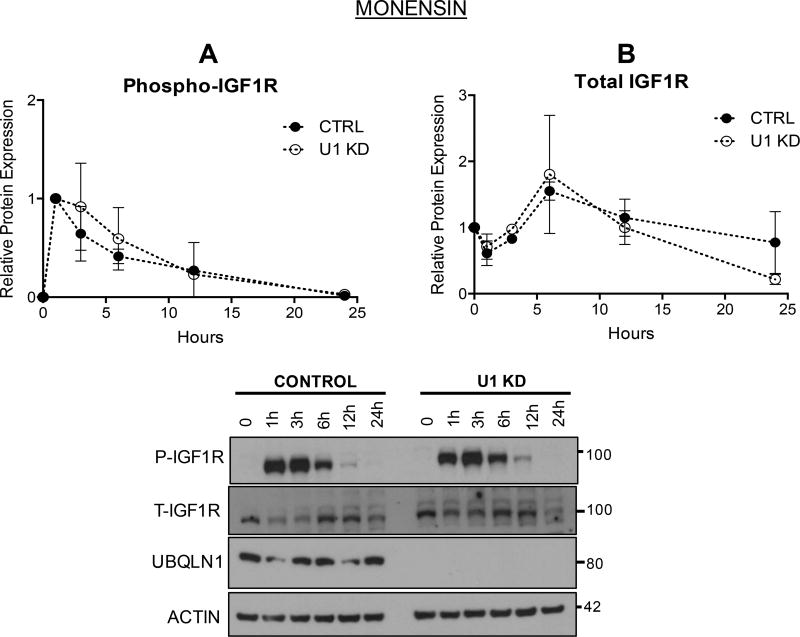

UBQLN1 stabilizes IGF1R during its trafficking

Since UBQLN1 deficient cells show accelerated loss of IGF1R, we investigated whether blocking receptor recycling and degradation pathways would prevent this loss using Monensin (an ionophore that traps internalized receptors within early endosomes, thereby preventing recycling of IGF1R to the cell surface and delaying lysosomal degradation) (Figure 5). There are no differences in pattern of phosphorylation of IGF1R between control and UBQLN1 deficient cells (Figure 5A). However, Monensin treatment caused accumulation of total receptor levels for up to 6 hours, followed by gradual degradation over next 18 hours (Figure 5B). When compared to Figure 4B, it appears that Monensin treatment prevents sustained expression of IGF1R in control cells and leads to receptor loss, mimicking effect of loss of UBQLN1 on IGF1R levels.

FIGURE 5. UBQLN1 stabilizes IGF1R during its trafficking.

A549 cells expressing shRNA against UBQLN1 and non-targeting control were serum starved for 12 hours followed by incubation with Monensin (10uM) (an early endosome inhibitor that traps internalized receptors and slows down recycling and receptors’ lysosomal turnover) an hour prior to stimulation with IGF1 and harvested post-stimulation at the indicated time points. Western Blot analysis for phosphorylated (A) and total receptor (B) levels were performed and graphed in both control and UBQLN1 deficient cells. Data are normalized to Actin in non-targeting shRNA control in unstimulated cells and represented as mean+/−SEM from 2 experiments.

Based on these data, we conclude that presence of UBQLN1 promotes stability of IGF1R, likely at the lysosomal level.

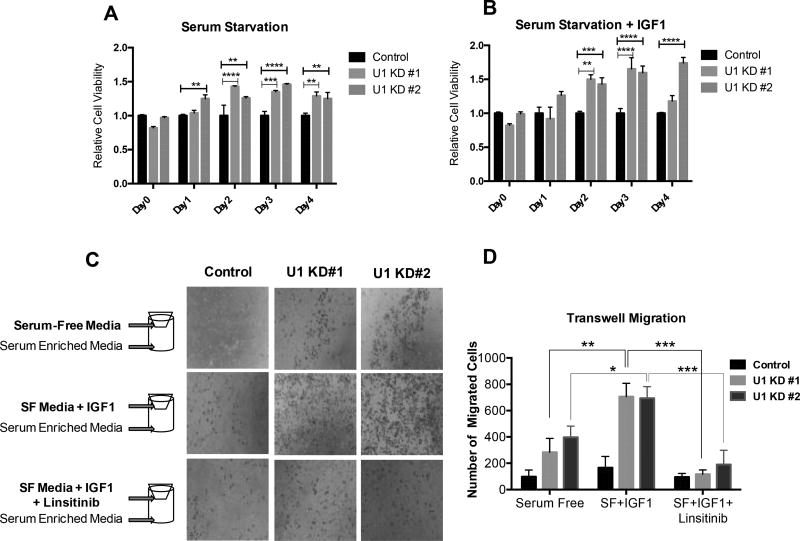

A549 cells that have loss of UBQLN1 show increased cell viability when cultured in serum-free conditions

Since IGF1R signaling is known to affect cellular survival, we performed a cell viability assay using Alamar Blue in A549 cells expressing stable shRNA against UBQLN1 (U1 KD#1, U1 KD#2, and control) in conditions of serum-free media and serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 for 4 days (Figure 6A,B). Alamar Blue readings were recorded to determine cell viability in control and UBQLN1 deficient cells for each day. When cultured in serum-free media, relative numbers of UBQLN1 deficient cells was higher compared to control cells for all days, starting day 1 (Figure 6A). Supplementing serum-free media with IGF1 (Figure 6B) corresponded with a slight increase in relative numbers of UBQLN1 deficient cells.

FIGURE 6. UBQLN1 deficient A549 cells show increased cell viability and migration potential when serum starved and upon stimulation of the IGF pathway.

(A,B) A549 cells expressing stable shRNA against UBQLN1 (U1 KD#1, U1 KD#2, and control) were cultured in conditions of serum-free media and serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 for 4 days. Alamar Blue readings were recorded every 24 hours and relative cell viability of UBQLN1 deficient cells were compared to control cells on each day. Day 2 onwards, UBQLN1 deficient cells gradually outsurvived control cells when cultured in serum-free media (A) and supplementing serum-free media with IGF1 (B) enhanced survival of these cells. Data are represented as mean±SEM from 2 independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, all relative to control in serum-free conditions. (C) A549 cells expressing stable shRNA against UBQLN1 (U1 KD#1, U1 KD#2, and control) were seeded in a transwell setup to assess cell migration in response to IGF1 stimulation. Cells were cultured in the top chamber in one of 3 conditions – serum-free media, serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 and serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 and Linsitinib, a small molecule inhibitor of IGF1R activity. Media supplemented with 10% FBS was used as chemo-attractant in the bottom chamber. At the end of 24 hours, cells were fixed and probed with HEMA 3 stain. Number of migrated cells were quantified by ImageJ software and analyzed by two-way ANOVA (D). Data are represented as mean±SEM from 3 independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, all relative to control.

Based on these data, we conclude that when A549 cells are serum starved, loss of UBQLN1 is advantageous from a survival perspective. Additionally, stimulation of IGF pathway enhanced survival in UBQLN1 deficient cells compared to control A549 cells.

Activation of IGF pathway in UBQLN1 deficient A549 cells increases their migration potential

We have previously published that lung adenocarcinoma cells that have loss of UBQLN1 are more migratory and invasive (11). Here, we investigated whether UBQLN1 deficient A549 cells migrate more in response to stimulation of the IGF pathway. In a transwell cell migration assay, cells were cultured in the top chamber in one of 3 conditions – serum-free media, serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 and serum-free media supplemented with IGF1 and Linsitinib (a small molecule inhibitor of IGF1R activity). Media supplemented with 10% FBS was used as chemo-attractant in the bottom chamber. At the end of 24 hours, pictures of migrated cells were captured (Figure 6C) and number of migrated cells were quantified by ImageJ software (Figure 6D). UBQLN1 deficient cells were inherently more migratory compared to control as observed in serum-free conditions. When stimulated with IGF1, there was a 3-fold increase in migration in UBQLN1 deficient cells compared to serum-free conditions (p<0.01). Cell migration returned to baseline with Linsitinib treatment in all cells and it appeared that UBQLN1 deficient cells were more sensitive to inhibition than control.

Based on these data, we conclude that an active IGF pathway may prime UBQLN1 deficient A549 cells to become more migratory.

DISCUSSION

UBQLN proteins are largely studied in the context of neurodegenerative diseases and their role is slowly emerging in the field of cancer. Among few published papers on UBQLN’s role in cancer, a recent study reported a positive correlation between increased UBQLN2 expression within osteosarcoma cells and tumor progression in patients. Similarly, increased urinary expression of UBQLN2 correlated with appropriate diagnosis, staging and grading of urothelial cancer (16). Our lab has published that UBQLN1 is lost and under-expressed in approximately 50% of non-small cell lung carcinomas. Cells that have loss of UBQLN1 adopt a more epithelial-to-mesenchymal (EMT) phenotype and are more migratory and invasive (11). In this manuscript, we determined a role for UBQLN1 in regulation of IGF1R, a receptor tyrosine kinase overexpressed in lung cancer.

We have previously determined that the fate of substrates that UBQLN1 associates with is interaction domain specific. Transmembrane proteins like BCLb (2) (17), ESYT2 (2), IGF1R (2), INSR (Figure S2A), IGF2R (not mapped) interact with UBQLN1 through its STI-1 and STI-2 domains and are stabilized as a result of this interaction. UBQLN1 interacts with all forms of IGF1R - non-processed immature form (pro-IGF1R) (Figure 2E), phosphorylated form and non-phosphorylated form (Figure 2D). It appears that UBQLN1 is recruited to IGF1R from the time of IGF1R synthesis and remains bound to the receptor during trafficking. Known binding partners of IGF1R like IRS (18), Shc (19), Grb2, Grb10 (20–24) are recruited to IGF1R only when the receptor is stimulated by ligand, auto-phosphorylated, and have undergone structural conformation to accommodate binding. IRS and Shc proteins are one of the first to bind to IGF1R which allows subsequent recruitment of additional molecules, and in turn stimulating other signaling pathways. GRB10 (direct recruitment) and GIGYF2 (recruitment through GRB10) bind to IGF1R (25) and have been identified as negative regulators of IGF1R phosphorylation. We found that UBQLN1 is a positive regulator of total IGF1R expression. Loss of UBQLN1 causes accelerated loss of IGF1R and overexpression of UBQLN1 stabilizes it (2).

Role of UBQLN has been studied in regulation of cell surface receptors like GABAA receptors (14), Presenilins (12,26,27), GPCR’s (28) and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (15). UBQLN1’s mechanism of regulation of IGF1R appears to be similar to its regulation of GABAA receptors (14,29). UBQLN1 interacts with GABAA receptors through its UBA domain. Loss of interaction led to decrease in receptor numbers, without an effect on rate of internalization or endocytosis. Similarly, loss of UBQLN1 in A549 cells causes decrease in receptor numbers of IGF1R. However, the ratio of active:total receptor is approximately 2 times higher compared to control (Figure 3B). Loss of UBQLN1 causes decreased mRNA expression of IGF1R (Figure 3E), therefore leading to a relatively small pool of IGF1R in UBQLN1 deficient cells. Thus, when new protein synthesis is blocked with Cycloheximide, IGF1 stimulation may lead to faster loss of this smaller pool of receptors compared to control. We have not determined whether UBQLN1 has a direct or indirect effect on gene transcription of IGF1R but based on our immunofluorescence data in variety of cell types – HeLa (Figure 1D), HEK293T (Figure 2B) and A549, H358 and HPL1D (data not shown), we have not detected nuclear presence of UBQLN1. Another reason for decreased transcription of IGF1R could be a possible negative feedback loop caused by a relatively active IGF pathway seen in UBQLN1 deficient cells leading to suppression of signal for new receptor synthesis. Once translated, multi-subunit proteins like IGF1R and GABAA receptors undergo maturation (assembly and processing) in the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) and Golgi before delivery and insertion to designated organelles. These protein subunits carry high mannose N-linked glycans sensitive to cleavage by an enzyme called Endo H. Overexpression of UBQLN1 caused a 30% increase in Endo H sensitive GABAA receptors in the ER thus implying that UBQLN1 may play a role in assembly of GABAA receptors in the ER (14). In our study, we found that UBQLN1 interacts with the pro-form of IGF1R (~135kD), indicating that it may also be involved in assembly and maturation of IGF1 receptors in the ER. It is yet to be determined how long after loss of interaction between UBQLN1 and IGF1R, does IGF1R expression begin to decrease. If the decrease in expression occurs within a matter of minutes after loss of interaction, it would indicate a stability/degradation based mechanism. However, if it takes hours, it would solidify UBQLN1’s role in assembly in the ER of IGF1R and other transmembrane proteins like INSR, BCLb, ESYT2 and OMP25.

UBQLN1 also interacts with other members of the IGF family, namely IGF2R and Insulin receptor (Figure 1B, Figure S2A), and UBQLN1 positively regulates expression of all 3 IGF receptors, especially when the receptors are activated by ligand. Furthermore, the ratio of active to inactive IGF1R was at least 2 times higher (Figure 3B) in UBQLN1 deficient cells. This may indicate that normal dephosphorylation of IGF1R may be delayed in absence of UBQLN1. Dephosphorylation of IGF1R is regulated by phosphatases like PTP1B and SHP2 in a ligand dependent manner (30), which are recruited to the plasma membrane via adaptor proteins like SHPS2. It is known that IntegrinαVβ3 acts via SHP2 to dephosphorylate IGF1R (31). It is a plausible hypothesis that UBQLN1 recruits phosphatases to the receptor for normal dephosphorylation directly or through participation in a multi-protein complex involving Integrins and other cell surface proteins that help recruit phosphatases to IGF1R to enable normal dephosphorylation.

We also tested for autocrine production of IGF ligands for a possible role in increased IGF pathway activation in UBQLN1 deficient cells. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that, there is decreased IGF1 production in these cells at the mRNA level compared to control when cultured in complete media or when serum starved for 3 days (Figure S3).

One of UBQLN1’s primary functions is protein quality control leading to either stabilization or degradation depending on the type of substrate. We have previously shown that transmembrane proteins like BCLb (17), ESYT2 and IGF1R are stabilized as a result of interaction with UBQLN1 and its UBA domain protects from MG132 (proteasomal inhibitor) mediated degradation in HEK293T cells (2). In the presence of Cycloheximide (Figure 4), we detected an accelerated loss of IGF1R when UBQLN1 is lost, thus confirming that presence of UBQLN1 stabilizes IGF1R expression. In response to Monensin treatment (an ionophore that traps internalized receptors and slows down recycling and receptors’ lysosomal turnover) (Figure 5), there was an overall accumulation of total IGF1R initially, but IGF1R levels started declining almost identically in both control and UBQLN1 deficient cells. Thus, when compared to changes in receptor expression with Cycloheximide exposure, it appears that loss of UBQLN1 and blocking lysosomal turnover with Monensin have similar effects on IGF1R degradation. These data indicate that UBQLN1 expression is required for IGF1R stability, and although more detailed investigation is required, it seems that UBQLN1 association with IGF1R protects the receptor while it is being trafficked through the lysosomes.

We then studied the biological relevance of UBQLN1’s association with IGF1R in context of cancer progression. We determined that UBQLN1 deficient A549 cells showed increased cell viability when serum-starved for 4 days (Figure 6A) and this survival effect was slightly enhanced when the IGF pathway was activated. This phenomena may be at least partially attributable to higher basal levels of pro-survival phospho-AKT protein in UBQLN1 deficient cells (Figure 3D). AKT is a key molecule, central to several signaling pathways like PI3K and RAS/MAPK and when phosphorylated, leads to evasion of apoptosis and promotes cell survival.

We have previously shown that lung adenocarcinoma cells that have loss of UBQLN1 show increased expression of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) markers and are more migratory (11). Here, we found that stimulating UBQLN1 deficient A549 cells with IGF1 increased their migratory potential 3-fold (Figure 6C,D). Active IGF signaling is known to promote cell migration through multiple pathways. It can promote cell motility by causing disassembly of adherens junctions and redistribution of movement fibers (32). In communication with the microenvironment, IGF1R signaling can induce expression of proteases like cathepsin D (33), matrix metalloproteinases (34,35) and urokinase plasminogen activator (36), promoting disintegration of basement membranes to facilitate cell migration. These proteases can also bind and cleave IGFBP3, which can release bound IGF1 for further stimulation (37). Integrin activation by components of the extracellular matrix can also regulate IGF1R signaling to stimulate cell migration (38). As UBQLN1 interacts with several plasma membrane proteins like IGF1R, INSR, IAP (39), it is worth testing whether UBQLN1 participates in a multi-protein complex with these receptors at the plasma membrane such that loss of UBQLN1 facilitates increased ECM-cell communication promoting migration.

The IGF pathway has been a major target of research for chemotherapy. However, drugs that seem effective in in vitro, in vivo, and in early phase trials fail to show overall clinical benefit. The IGF pathway is complicated with presence of different receptor types including hybridization between receptors, multiple ligands, autocrine and paracrine stimulation, extensive influence of extracellular matrix signals, and compensatory signaling via other growth factor receptors. Additionally, intracellular IGF1R activity does not always correlate with its cell surface expression. We have also observed that IGF1R expression varies with cell confluence in vitro (data not shown). All these factors make it challenging to predict response to therapy thus highlighting the role of defining better biomarker profiles for choosing patients for anti-IGF1R therapy. Therefore, it is essential to study cellular and extracellular factors that regulate activity of IGF1R directly or indirectly. Our data indicate that UBQLN1 expression is one such candidate. Future studies investigating role of UBQLN1 in IGF pathway mediated tumorigenesis, metastasis, response and resistance to therapy are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by an NCI R01 R01CA193220 to LJB, funds from James Graham Brown Cancer Center, University of Louisville and Kosair Pediatric Cancer Program to Levi J. Beverly, and Arno Spatola Endowment Graduate Research Fellowship by IMD3, University of Louisville, KY and IPIBS Graduate Fellowship, University of Louisville, KY to Zimple Kurlawala. RD was supported by an R25 Cancer education program grant from the National Cancer Center R25CA134283.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Author contributions:

ZK conducted most of the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. RD conducted experiments with Monensin. PPS assisted in cell viability and Transwell migration assay. BPC helped design inhibitor experiments. LJS and LJB aided in overall project design and data interpretation.

References

- 1.Yarden Y. The EGFR family and its ligands in human cancer. signalling mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. European journal of cancer. 2001;37(Suppl 4):S3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurlawala Z, Shah PP, Shah C, Beverly LJ. The STI and UBA Domains of UBQLN1 are Critical Determinants of Substrate Interaction and Proteostasis. J Cell Biochem. 2017 doi: 10.1002/jcb.25880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renehan AG, O'Connell J, O'Halloran D, Shanahan F, Potten CS, O'Dwyer ST, Shalet SM. Acromegaly and colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, biological mechanisms, and clinical implications. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35:712–725. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laron Z. The GH-IGF1 axis and longevity. The paradigm of IGF1 deficiency. Hormones (Athens) 2008;7:24–27. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1111034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brahmkhatri VP, Prasanna C, Atreya HS. Insulin-like growth factor system in cancer: novel targeted therapies. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:538019. doi: 10.1155/2015/538019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimberg A. Mechanisms by which IGF-I may promote cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:630–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peschard P, Fournier TM, Lamorte L, Naujokas MA, Band H, Langdon WY, Park M. Mutation of the c-Cbl TKB domain binding site on the Met receptor tyrosine kinase converts it into a transforming protein. Molecular cell. 2001;8:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakagawa M, Uramoto H, Oka S, Chikaishi Y, Iwanami T, Shimokawa H, So T, Hanagiri T, Tanaka F. Clinical significance of IGF1R expression in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vigneri PG, Tirro E, Pennisi MS, Massimino M, Stella S, Romano C, Manzella L. The Insulin/IGF System in Colorectal Cancer Development and Resistance to Therapy. Front Oncol. 2015;5:230. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janssen JA, Varewijck AJ. IGF-IR Targeted Therapy: Past, Present and Future. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:224. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah PP, Lockwood WW, Saurabh K, Kurlawala Z, Shannon SP, Waigel S, Zacharias W, Beverly LJ. Ubiquilin1 represses migration and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2015;34:1709–1717. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mah AL, Perry G, Smith MA, Monteiro MJ. Identification of ubiquilin, a novel presenilin interactor that increases presenilin protein accumulation. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:847–862. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.4.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Li Z, Gu J, Zhang Y, Wang W, Shen H, Chen G, Wang X. Plic-1, a new target in repressing epileptic seizure by regulation of GABAAR function in patients and a rat model of epilepsy. Clinical Science. 2015;129:1207–1223. doi: 10.1042/CS20150202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saliba RS, Pangalos M, Moss SJ. The ubiquitin-like protein Plic-1 enhances the membrane insertion of GABAA receptors by increasing their stability within the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18538–18544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802077200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ficklin MB, Zhao S, Feng G. Ubiquilin-1 regulates nicotine-induced up-regulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34088–34095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimada K, Fujii T, Tatsumi Y, Anai S, Fujimoto K, Konishi N. Ubiquilin2 as a novel marker for detection of urothelial carcinoma cells in urine. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:3–9. doi: 10.1002/dc.23332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beverly LJ, Lockwood WW, Shah PP, Erdjument-Bromage H, Varmus H. Ubiquitination, localization, and stability of an anti-apoptotic BCL2-like protein, BCL2L10/BCLb, are regulated by Ubiquilin1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E119–126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119167109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang LM, Myers MG, Jr, Sun XJ, Aaronson SA, White M, Pierce JH. IRS-1: essential for insulin- and IL-4-stimulated mitogenesis in hematopoietic cells. Science. 1993;261:1591–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.8372354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wills MK, Jones N. Teaching an old dogma new tricks: twenty years of Shc adaptor signalling. Biochem J. 2012;447:1–16. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dufresne AM, Smith RJ. The adapter protein GRB10 is an endogenous negative regulator of insulin-like growth factor signaling. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4399–4409. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein EG, Gustafson TA, Hubbard SR. The BPS domain of Grb10 inhibits the catalytic activity of the insulin and IGF1 receptors. FEBS Lett. 2001;493:106–111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori K, Giovannone B, Smith RJ. Distinct Grb10 domain requirements for effects on glucose uptake and insulin signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;230:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos FJ, Langlais PR, Hu D, Dong LQ, Liu F. Grb10 mediates insulin-stimulated degradation of the insulin receptor: a mechanism of negative regulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E1262–1266. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00609.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langlais P, Dong LQ, Ramos FJ, Hu D, Li Y, Quon MJ, Liu F. Negative regulation of insulin-stimulated mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling by Grb10. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:350–358. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giovannone B, Tsiaras WG, de la Monte S, Klysik J, Lautier C, Karashchuk G, Goldwurm S, Smith RJ. GIGYF2 gene disruption in mice results in neurodegeneration and altered insulin-like growth factor signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4629–4639. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massey LK, Mah AL, Ford DL, Miller J, Liang J, Doong H, Monteiro MJ. Overexpression of ubiquilin decreases ubiquitination and degradation of presenilin proteins. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:79–92. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massey LK, Mah AL, Monteiro MJ. Ubiquilin regulates presenilin endoproteolysis and modulates gamma-secretase components, Pen-2 and nicastrin. Biochem J. 2005;391:513–525. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.N'Diaye EN, Hanyaloglu AC, Kajihara KK, Puthenveedu MA, Wu P, von Zastrow M, Brown EJ. The ubiquitin-like protein PLIC-2 is a negative regulator of G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1252–1260. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bedford FK, Kittler JT, Muller E, Thomas P, Uren JM, Merlo D, Wisden W, Triller A, Smart TG, Moss SJ. GABA(A) receptor cell surface number and subunit stability are regulated by the ubiquitin-like protein Plic-1. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:908–916. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buckley DA, Cheng A, Kiely PA, Tremblay ML, O'Connor R. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor type I (IGF-I) receptor kinase activity by protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP-1B) and enhanced IGF-I-mediated suppression of apoptosis and motility in PTP-1B-deficient fibroblasts. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:1998–2010. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.1998-2010.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rocchi S, Tartare-Deckert S, Sawka-Verhelle D, Gamha A, van Obberghen E. Interaction of SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 with the insulin receptor and the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor: studies of the domains involved using the yeast two-hybrid system. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4944–4952. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox OT, O'Shea S, Tresse E, Bustamante-Garrido M, Kiran-Deevi R, O'Connor R. IGF-1 Receptor and Adhesion Signaling: An Important Axis in Determining Cancer Cell Phenotype and Therapy Resistance. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015;6:106. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang F, Duan R, Chirgwin J, Safe SH. Transcriptional activation of cathepsin D gene expression by growth factors. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;24:193–202. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0240193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon A, Hurta RA. Insulin like growth factor-1 selectively regulates the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in malignant H-ras transformed cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;223:1–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1017549222677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang D, Brodt P. Type 1 insulin-like growth factor regulates MT1-MMP synthesis and tumor invasion via PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling. Oncogene. 2003;22:974–982. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunn SE, Torres JV, Oh JS, Cykert DM, Barrett JC. Up-regulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator by insulin-like growth factor-I depends upon phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1367–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen P, Graves HC, Peehl DM, Kamarei M, Giudice LC, Rosenfeld RG. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is an insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 protease found in seminal plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:1046–1053. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.4.1383255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clemmons DR, Maile LA. Minireview: Integral membrane proteins that function coordinately with the insulin-like growth factor I receptor to regulate intracellular signaling. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1664–1670. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu AL, Wang J, Zheleznyak A, Brown EJ. Ubiquitin-related proteins regulate interaction of vimentin intermediate filaments with the plasma membrane. Mol Cell. 1999;4:619–625. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.