Abstract

Background

Globally, an estimated 2 billion people lack access to surgical and anesthesia care. We sought to pool results of anesthesia care capacity assessments in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to identify patterns of deficits and provide useful targets for advocacy and intervention.

Methods

A systematic review of PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Google Scholar identified reports that documented anesthesia care capacity from LMICs. When multiple assessments from one country were identified, only the study with the most facilities assessed was included. Patterns of availability or deficit were described.

Results

We identified 22 LMICs (15 low- and 8 middle-income countries) with anesthesia care capacity assessments (614 facilities assessed). Anesthesia care resources were often unavailable, including relatively low-cost ones (e.g., oxygen and airway supplies). Capacity varied markedly between and within countries, regardless of the national income. The availability of fundamental resources for safe anesthesia, such as airway supplies and functional pulse oximeters, was often not reported (72 and 36 % of hospitals assessed, respectively). Anesthesia machines and the capability to perform general anesthesia were unavailable in 43 % (132/307 hospitals) and 56 % (202/361) of hospitals, respectively.

Conclusion

We identified a pattern of critical deficiencies in anesthesia care capacity in LMICs, including some low-cost, high-value added resources. The global health community should advocate for improvements in anesthesia care capacity and the potential benefits of doing so to health system planners. In addition, better quality data on anesthesia care capacity can improve advocacy, as well as the monitoring and evaluation of changes over time and the impact of capacity improvement interventions.

Introduction

Over the past decades, the global health community has begun to appreciate the large burden of conditions that require essential surgical and trauma care [1]. In response, the World Health Organization (WHO) created the Global Initiative for Essential and Emergency Surgical Care (GIEESC) to frame ways in which this burden might be addressed [2]. This initiative provided an outline for assessing, planning, and organizing surgical and anesthesia care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and became the impetus for a number of surgical and anesthesia care capacity assessments.

In 2008, poor-expenditure countries (i.e., countries that spend less than USD 100 on health care per capita per annum) accounted for only 3.5 % of the worldwide surgical caseload despite accounting for 35 % of the global population, suggesting significant unmet needs for surgical and anesthetic care [3]. Over the same time period, the WHO and World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists developed a series of recommendations for anesthesia resource allocation by hospital type [4]. The availability of the resources discussed in these guidelines has not been assessed in a multi-country, income-stratified format, which can be used to identify specific patterns of good and poor availability of anesthesia resources.

To address this gap, and in lieu of better data, we pooled data from individual anesthesia care capacity assessments in LMICs to create an overall picture of the anesthesia care capacity worldwide. By doing so, the findings might highlight gaps in anesthesia resources and patterns of availability.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted using PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Google Scholar. Keywords that represented ‘surgery’ and ‘anesthesia’ were combined with terms that represented ‘capacity’ and ‘assessment’ in a database-specific manner (Appendix).

We included all reports that assessed anesthesia care capacity in a LMIC published before June 1st, 2015. The World Bank’s World Development Report was used to define LMICs for the review. If multiple studies from a single country were found, only the study with the most facilities was included.

Assessment tools

Three assessment tools were used by retrieved reports: WHO Tool for Situational Analysis to Assess Emergency and Essential Surgical Care; PIPES Surgical Assessment Tool; and the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative Assessment Tool.

The WHO Tool for Situational Analysis to Assess Emergency and Essential Surgical Care was developed in 2007 by members of the GIEESC. [5, 6] It includes a 256-item questionnaire that assesses four areas: (i) infrastructure, (ii) human resources, (iii) types of surgical procedures performed, and (iv) available equipment.

The PIPES Surgical Assessment tool is a modification of the WHO tool that was designed to capture binary data based on the four WHO resource areas to improve both ease of analysis and comparison between countries [7]. PIPES is significantly shorter than the WHO tool (105 items), and excludes many of the explanatory questions clarifying why certain procedures were not performed in given hospitals. The PIPES tool has been validated in a number of countries; [8, 9] however, given the ubiquity of the WHO tool, we only used PIPES results when WHO results from the same country were not available (e.g., Nigeria, Sierra Leone).

Results from Guyana and Ethiopia were collected via a modified WHO survey developed by the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative. [10, 11] Results from one country, Uganda, were gathered by a unique survey tool developed specifically for that country [12].

Data management

Three reviewers (RAH, MCM, and SSC) screened all reports; a third reviewer (ALK) evaluated the report if there was any disagreement. Two reviewers (RAH, SSC) independently extracted the data.

To determine the overall availability of anesthesia resources, we extracted assessment results from each report for a list of specific resources. In some cases, availability of resources was expressed in percentages and in some cases in raw numbers; to provide comparable results, we converted percentages into number of facilities assessed and calculated means based on the total number of resources available divided by hospitals assessed per resource.

Data analysis

Proportions of hospitals with each resource in each country assessment were pooled using a fixed-effect model with Stata v13 (StataCorp, TX, USA). Weights were applied based on the capacity assessment sample size. Confidence intervals were calculated with a binomial distribution. Estimates of heterogeneity were calculated from the inverse-variance fixed-effect model. Significant intra-group heterogeneity was identified (i.e., I2 was >75 % with corresponding p values <0.05). To explore this further, we calculated pooled estimates by subgroup (i.e., low-income and middle-income countries) using a random effects model. Despite these efforts, the I2 measure demonstrated substantial intra-group and inter-group heterogeneity. Thus, pooled estimates are not reported. Instead, we present a narrative synthesis of the resources’ availability as per recommendations offered by The Cochrane Collaboration. [13]

Specifically, Forest plots without the pooled estimates are presented for electricity, oxygen supply, pulse oximeter, and anesthesia machine to demonstrate the variability of resource availability between assessments. A fixed continuity correction was added for assessments that had either no hospital with the resource available or all hospitals with the resource available to allow the use of nonnegative constants. The availability of these four resources that span the continuum of anesthesia care development give useful information about the respective national capacity more broadly. For these resources and the remainder of resources that were reported less frequently, percentages of hospitals with the available resource are provided in the text and are accompanied by the number of hospitals with the resource and the number of hospitals that had the resource assessed.

Results

Search results

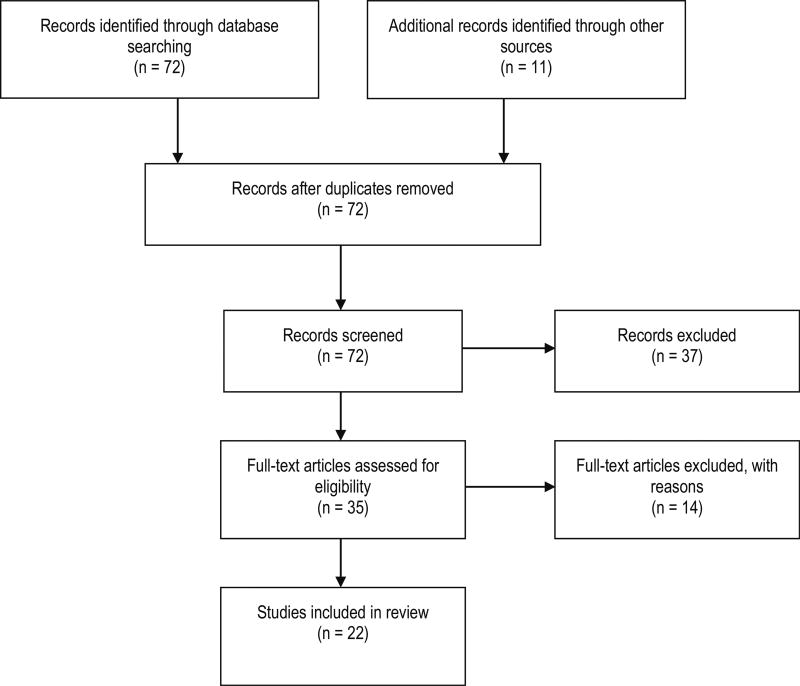

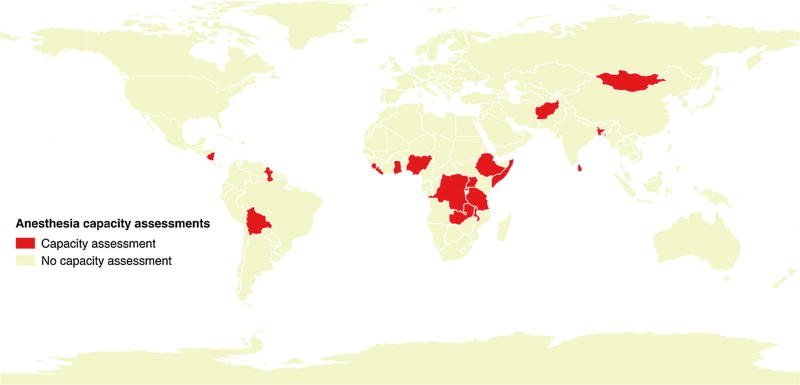

The systematic search returned 82 records (Fig. 1). Of these, 11 (13 %) were duplicates and were removed. The remaining 71 records were screened for relevance. Thirty-five full-text reports were evaluated. After excluding reports without anesthesia care capacity assessment, 22 reports were included (27 % of all records retrieved) that described anesthesia care capacity in 614 hospitals in 22 LMICs (Fig. 2). However, the number of and specific anesthesia resources reported per assessment varied markedly (median 7 resources, range 3–10) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the systematic search

Fig. 2.

Countries that have reported an anesthesia care capacity assessment identified by systematic review

Table 1.

Anesthesia care capacity assessments identified by systematic review

| Country | Author | Year | National income |

Number of hospitals assessed |

Tool used | Number of resources reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sierra Leone [21] | Kingham | 2009 | Low | 12 | PIPES | 3 |

| Liberia [19] | Sherman | 2011 | Low | 16 | WHO | 6 |

| Uganda [13] | Walker | 2010 | Low | 72 | Other | 1 |

| Rwanda [26] | Petroze | 2012 | Low | 44 | WHO | 9 |

| Tanzania [27] | Penoyar | 2012 | Low | 48 | WHO | 10 |

| Ethiopia [12] | Chao | 2012 | Low | 20 | Other | 6 |

| Gambia [28] | Iddriss | 2011 | Low | 18 | WHO | 7 |

| Solomon Islands [29] | Natuzzi | 2011 | Low | 9 | WHO | 5 |

| Bangladesh [30] | Lebrun | 2013 | Low | 14 | WHO | 7 |

| Afghanistan [31] | Contini | 2010 | Low | 17 | WHO | 8 |

| Somalia [32] | Elkheir | 2014 | Low | 14 | WHO | 10 |

| Malawi [33] | Henry | 2014 | Low | 27 | PIPES | 9 |

| Dem. Rep. Congo [34] | Sion | 2015 | Low | 12 | WHO | 4 |

| Sri Lanka [18] | Taira | 2010 | Middle | 31 | WHO | 4 |

| Mongolia [35] | Spiegel | 2011 | Middle | 44 | WHO | 10 |

| Bolivia [36] | Lebrun | 2012 | Middle | 18 | WHO | 7 |

| Nicaragua [37] | Solis | 2013 | Middle | 28 | WHO | 8 |

| Ghana [20] | Choo | 2010 | Middle | 17 | WHO | 12 |

| Zambia [38] | Bowman | 2008 | Middle | 103 | WHO | 3 |

| Nigeria [25] | Henry | 2012 | Middle | 41 | WHO | 3 |

| Guyana [10] | Vansell | 2015 | Middle | 9 | Other | 3 |

National income was defined by the World Bank’s World Development Report. WHO WHO Tool for Situational Analysis to Assess Emergency and Essential Surgical Care, PIPES PIPES Surgical Assessment tool, Dem. Rep. Congo Democratic Republic of the Congo

Infrastructure and equipment capacity

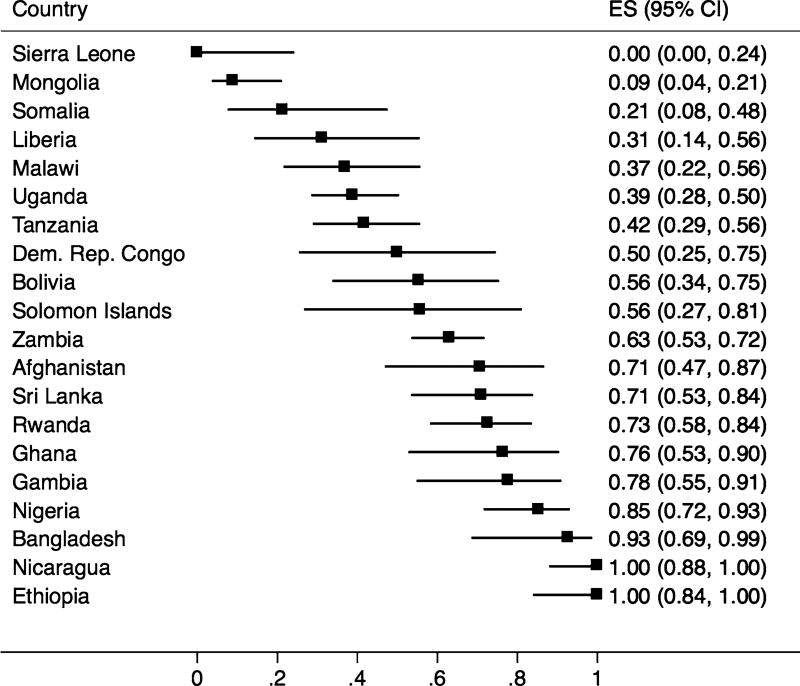

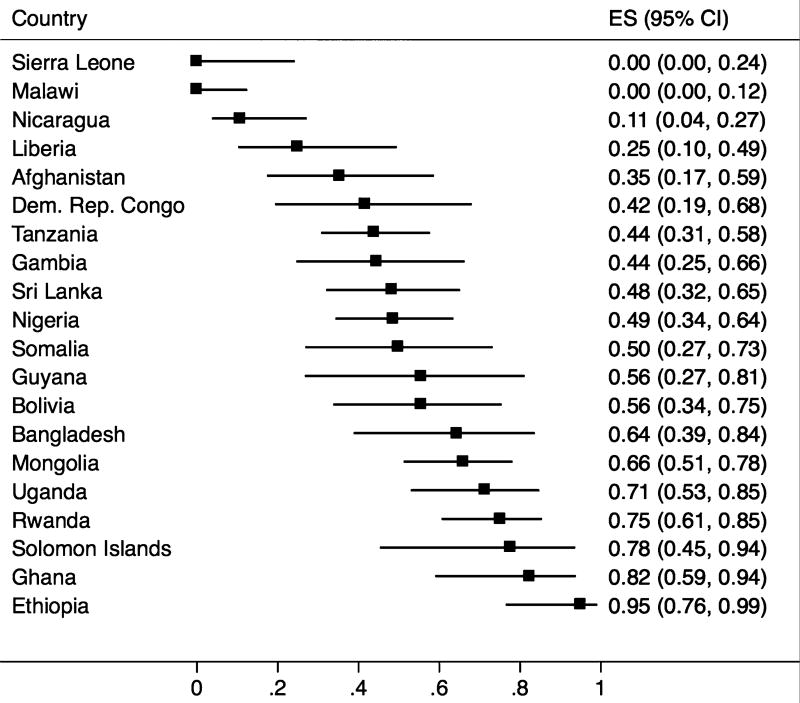

Only 50 % of hospitals assessed (234/467 hospitals) had consistent electricity. This ranged from no hospitals assessed in Sierra Leone to all hospitals assessed in Nicaragua and Ethiopia (Fig. 3). Sixty-one percent of hospitals had continuous supply of oxygen in the operating room (345/561 hospitals). Sierra Leone and Malawi reported that no hospital assessed had continuous oxygen supply (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of hospitals with continuous electricity from surgical and anesthesia capacity assessments in low- and middle-income countries. ES effect size (i.e., proportion of hospitals with the resource available), 95 % CI 95 % confidence interval calculated using the binomial distribution, Dem. Rep. Congo Democratic Republic of the Congo

Fig. 4.

Proportion of hospitals with oxygen supply from surgical and anesthesia capacity assessments in low- and middle-income countries. ES effect size (i.e., proportion of hospitals with the resource available), 95 % CI 95 % confidence interval calculated using the binomial distribution; Dem. Rep. Congo Democratic Republic of the Congo

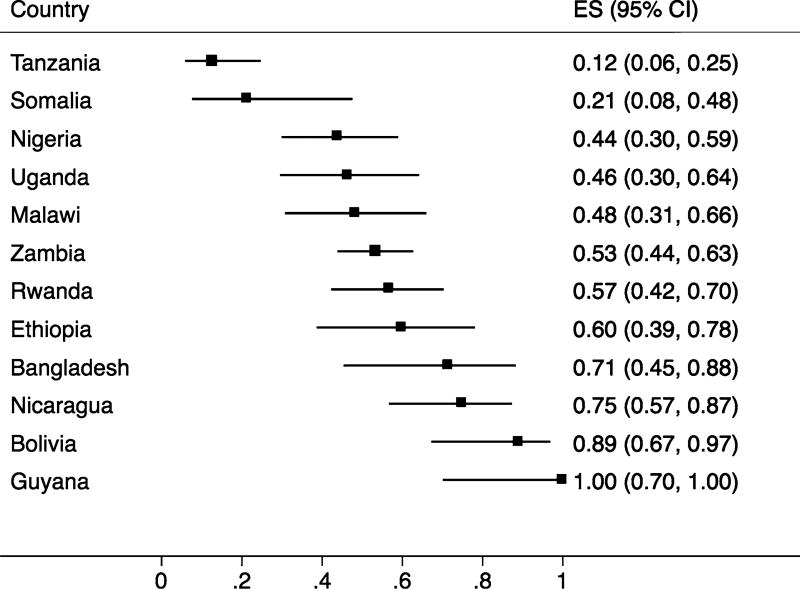

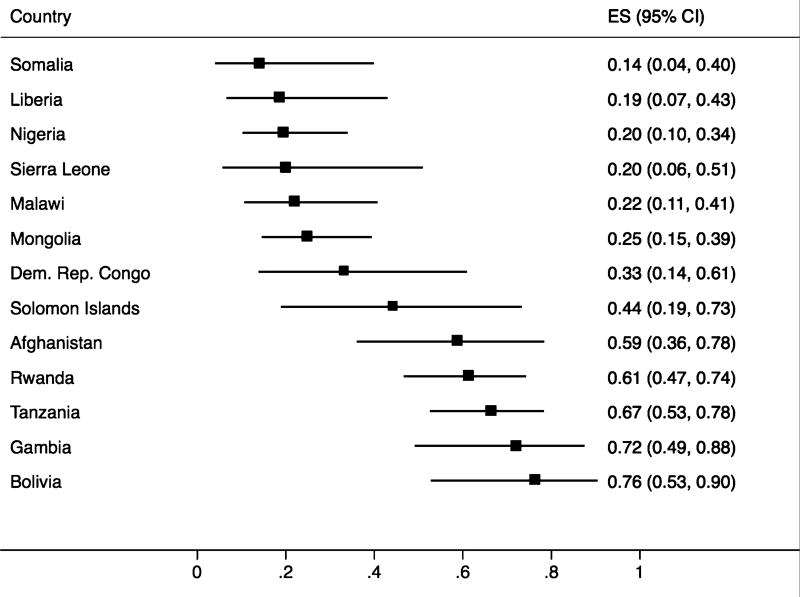

Although not reliably reported (12 countries), functional pulse oximeters were present in 51 % of the hospitals assessed (201/394 hospitals), ranging from 12 % of hospitals in Tanzania to 100 % of hospitals in Guyana (Fig. 5). Similarly, only 13 countries reported functional anesthesia machine availability (Fig. 6). Of those, only 43 % of hospitals had at least one functioning anesthesia machine (132/307 hospitals).

Fig. 5.

Proportion of hospitals with continuous functional pulse oximeters from surgical and anesthesia capacity assessments in low- and middle-income countries. ES effect size (i.e., proportion of hospitals with the resource available), 95 % CI 95 % confidence interval calculated using the binomial distribution

Fig. 6.

Proportion of hospitals with functional anesthesia machines from surgical and anesthesia capacity assessments in low- and middle-income countries. ES effect size (i.e., proportion of hospitals with the resource available) 95 % CI 95 % confidence interval calculated using the binomial distribution, Dem. Rep. Congo Democratic Republic of the Congo

Anesthesia capability

Of the 361 hospitals that reported capacity for anesthesia type (59 % of assessed hospitals), 56 % (202 hospitals) reported having the capacity to perform general anesthesia, 66 % could provide spinal, and 57 % regional anesthesia.

Only 327 hospitals reported capacity for anesthetic techniques more specifically. Of these, ketamine was the anesthetic most frequently employed (73 % of hospitals surveyed; 124/171 hospitals).

Other anesthesia capabilities

Only 170 hospitals in Africa and Asia reported on surgical airway capabilities and other airway supplies. Of these, 22 % reported having equipment to perform a cricothyroidotomy (37/170 hospitals); 48 % (51/109) reported a consistent supply of adult endotracheal tubes; and 42 % reported a consistent supply of pediatric endotracheal tubes (71/170).

Discussion

Large deficiencies exist in anesthesia capacity in LMICs. Despite limitations in the reporting of data by various groups using various assessment tools, we described anesthesia care capacity in LMICs to document patterns in anesthesia resource deficiencies and consider ways in which they might be overcome. We documented generally low and variable availability of anesthesia resources both between and within countries. Between 30 and 50 % of the hospitals surveyed reported not having continuous oxygen supply and/or continuous electricity. Around half of the hospitals had the resources and training required for definitive airway management and/or general anesthesia. Fewer still had functional anesthesia machines or pulse oximeters, and less than half reported consistent supply of basic equipment for airway management.

Many of the resources aforementioned are relatively low cost and provide significant added value to healthcare regardless of the context (e.g., airway supplies, oxygen, and electricity). Thus, health system planners should consider these resources as essential for the health of their population and prioritize their availability over more advanced equipment and supplies (e.g., anesthesia machines and advanced diagnostic imaging). Improving these resources might require dedicated financing streams, as have been done for HIV and maternal health, as well as improving the supply chain for non-drug consumables (e.g., airway supplies) [14]. Additionally, anesthesia training must be improved in concert with improvements in equipment and supply availability to avoid wasteful mismatch of human and physical resources [15]. Such initiatives might significantly improve the safety and availability of essential surgical care, which will have considerable benefits for population health [16].

Although the capacity assessments did not often describe the anesthesia workforce, other reports have documented insufficient numbers of adequately trained personnel who can provide safe anesthesia [17]. Thus, the paucity of anesthesia care capacity is even more striking when this is considered [18]. Many countries rely upon nurse anesthetists to provide safe anesthesia; however, anesthesia care in LMICs or in remote areas is often provided by technicians and/or nurses with highly variable on-the-job training [19–21]. With anesthesia care provided by an insufficient workforce who are equipped with less than a bare minimum of essential anesthesia resources, the safety of anesthesia care in LMICs is concerning and requires close evaluation. Efforts to do so could be improved by routine data collection of indicators (e.g., perioperative mortality rate and day of surgery mortality rate) and quality improvement programs (e.g., morbidity and mortality conferences and perioperative death reviews). Further, the availability of other standard monitors as defined in the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Standards for Basic Anesthesia Monitoring [22], such as continuous electrocardiogram and capnographic monitoring, should be incorporated into future assessments of anesthesia care resource availability. Capacity assessments have proven useful if done serially to monitor changes over time or evaluate the impact of an intervention [23, 24].

Though useful in providing a snapshot of the magnitude of the problem, this study has multiple significant limitations. Most significant is the lack of consistently reported anesthesia care resources between reports, varying reporting mechanisms, and differences in overall methodologies (e.g., sampling strategy). In addition, only data from 22 countries were available. The data reported varied extensively between and within countries and various assessment tools were used. However, we were able to identify important patterns, such as the lack of electricity and oxygen, particularly in low-income countries. Also, a different survey team performed each assessment. While this may have resulted in some degree of unreliability within the survey responses, the tools have been validated for multi-country use. Lastly, given the paucity of available data, different reporting schemes, and markedly varied results, we were unable to provide a pooled estimate.

Despite these limitations, the findings from this review allow reasonable conclusions to be drawn about the critical deficiencies in anesthesia resources in LMICs. Although one must be careful in extrapolating data, the results will not be surprising to those providing anesthesia in a LMIC who are in urgent need of improved infrastructure, equipment, and supplies. Future assessments targeted more specifically at the availability of anesthesia resources, anesthesia training, and anesthesia safety which are needed to further characterize anesthesia capacity in these settings. We hope that future studies will be more consistent in their reporting and allow for greater generalizability.

Conclusion

This review combined data from anesthesia capacity assessments in 22 LMICs with a goal of describing deficiencies and considering ways in which anesthesia capacity might be improved. We discovered that anesthesia resources are often not available when needed. However, detailed description and analysis of specific resources was not possible given the differences in assessments. As the importance of surgical and anesthesia in global health has been established, international organizations and individual countries must increase focus and funding directed toward the provision of safe perioperative care in LMICs. This should include the reliable provision of essential anesthesia resources, training of new and current anesthesia care providers, and monitoring and evaluation of anesthesia care.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded, in part, by Grant R25-TW009345 from the Fogarty International Center, US National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

PubMed, Google Scholar, and MEDLINE were searched on 6/13/2013 and again on 8/11/2015 for the period 1998-present:

Surgical capacity,

Survey tool,

“Surgical capacity” and “survey tool,”

GIEESC,

WHO surgical capacity,

PIPES,

“GIEESC” and “survey tool,” and

“PIPES” and “survey tool.”

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None.

References

- 1.Vo D, Cherian MN, Bianchi S, et al. Anesthesia capacity in 22 low and middle income countries. J Anes Clin Res. 2012;3:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care. [Accessed 10 Oct 2015];2015 http://www.who.int/surgery/esc_about/en/

- 3.Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modeling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008;372:139–144. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merry AF, Cooper JB, Soyannwo O, et al. International standards for a safe practice of anesthesia 2010. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57:1027–1034. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9381-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choo S. [Accessed 10 Oct 2015];WHO’s Integrated Management for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) tool kit. 2012 http://www.ghdonline.org/surgery/discussion/whos-integrated-management-for-emergency-and-ess March 10, 2012.

- 6.Who EESC Global Database. [Accessed 10 Oct 2015];2015 http://who.int/surgery/eesc_database/en/

- 7.Markin A, Barbero R, Leow JJ, et al. Inter-Rater reliability of the PIPES tool: validation of a surgical capacity index for use in resource-limited settings. World J Surg. 2014;38:2195–2199. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groen RS, Kamara TB, Dixon-Cole R, et al. A tool and index to assess surgical capacity in low-income countries: an initial implementation in Sierra Leone. World J Surg. 2012;36:1970–1977. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markin A, Barbero R, Leow JJ, et al. Inter-rater reliability of the PIPES tool: validation of a surgical capacity index for use in resource-limited settings. World J Surg. 2014;38:2195–2199. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vansell HJ, Schlesinger JJ, Harvey A, et al. Anaesthesia, surgery, obstetrics and emergency care in Guyana. J Epi Glob Health. 2015;5:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao TE, Burdic M, Ganjawalla K, et al. Survey of surgery and anesthesia infrastructure in Ethiopia. World J Surg. 2012;36:2545–2553. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1729-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker IA, Obua AD, Falan M, et al. Pediatric surgery and anaesthesia in southwestern Uganda: a cross-sectional survey. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:897–906. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.076703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan R. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. [Accessed 27 Oct 2015];Heterogeneity and subgroup analyses in Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group reviews: planning the analysis at protocol stage. 2014 http://cccrg.cochrane.org February 2014.

- 14.Chin RJ, Sangmanee D, Piergallini L. PEPFAR funding and reduction in HIV infection rates in Sub-Saharan African countries: a quantitative analysis. Int J MCH AIDS. 2015;3:158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubowitz G, Detlefs S, McQueen KA. Global anesthesia workforce crisis: a preliminary survey revealing shortages contributing to undesirable outcomes and unsafe practices. World J Surg. 2010;34:438–444. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0229-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mock CN, Donkor P, Gawande A, et al. Essential surgery: key messages from Disease Control Priorities. Lancet. (3) 2015;385:2209–2219. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60091-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyler M, Finlayson SR, McClain CD, et al. Shortage of doctors, shortage of data: a review of the global surgery, obstetrics and anesthesia workforce literature. World J Surg. 2014;38:269–280. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2324-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taira BR, Cherian MN, Yakandawala H, et al. Survey of emergency and surgical capacity in the conflict-affected regions of Sri Lanka. World J Surg. 2010;34:428–432. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman L, Clement PT, Cherian MN, et al. Implementing Liberia’s poverty reduction strategy: an assessment of emergency and essential surgical services. Arch Surg. 2011;146:35–39. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choo S, Perry H, Hesse AAJ, et al. Assessment of capacity for surgery, obstetrics and anaesthesia in 17 Ghanaian hospitals using a WHO assessment tool. Trop Med and Int Health. 2010;15:1109–1115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingham TP, Kamara TB, Cherian MN, et al. Quantifying surgical capacity in Sierra Leone: a guide for improving surgical care. Arch Surg. 2009;144:122–127. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Society of Anesthesiologists House of Delegates. [Accessed 19 September 2015];Standards for basic anesthetic monitoring. 2011 http://www.asahq.org/…/standards-for-basic-anesthetic-monitoring/en/1.

- 23.Stewart BT, Quansah R, Gyedu A. Serial assessment of trauma care capacity in Ghana in 2004 and 2014. JAMA Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlson LC, Lin JA, Ameh EA. Moving from data collection to application: a systematic literature review of surgical capacity assessments and their applications. World J Surg. 2015;39:813–821. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2938-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry JA, Windapo O, Kushner AL, et al. A survey of surgical capacity in rural Southern Nigeria: opportunities for change. World J Surg. 2012;36:2811–2818. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1764-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petroze RT, Nzayisenga A, Rusanganwa V, et al. Comprehensive national analysis of emergency and essential surgical capacity in Rwanda. Br J Surg. 2012;2012(99):436–442. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penoyar R, Cohen H, Kibatala P, et al. Emergency and surgery services of primary hospitals in the United Republic of Tanzania. BMJ Open. 2012;2:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Idriss A, Shivute N, Bickler S, et al. Emergency, anaesthetic and essential surgical capacity in the Gambia. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:565–572. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.086892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Natuzzi ES, Kushner A, Jagilly R, et al. Surgical care in the Solomon Islands: a road map for universal surgical care delivery. World J Surg. 2011;35:1183–1193. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeBrun DG, Dhar D, Sarkar MIH, et al. Measuring global surgical disparities: a survey of surgical and anesthesia infrastructure in Bangladesh. World J Surg. 2013;37:24–31. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Contini S, Taqudeer A, Cherian M, et al. Emergency and essential services in Afghanistan: still a missing challenge. World J Surg. 2010;34:473–479. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elkheir N, Sharma A, Cherian M, et al. A cross-sectional survey of essential surgical capacity in Somalia. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004360. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henry JA, Frenkel E, Borgstein E, et al. Surgical and anaesthetic capacity of hospitals in Malawi: key insights. Health Policy Plan. 2014 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sion M, Rajan D, Kalambay H, et al. A resource planning analysis of district hospital surgical services in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Global Sci Health Pract. 2015;3:56–70. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegel DA, Choo S, Cherian M, et al. Quantifying surgical and anaesthetic availability at primary health facilities in Mongolia. World J Surg. 2011;35:272–279. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LeBrun DG, Saavedra-Pozo I, Agreda-Flores F, et al. Surgical and anesthesia capacity in Bolivian public hospitals: results from a national hospital survey. World J Surg. 2012;36:2559–2566. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1722-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solis C, Leon P, Sanchez N, et al. Nicaraguan surgical and anesthesia infrastructure: survey of Ministry of Health Hospitals. World J Surg. 2013;37:2109–2121. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowman KG, Jovic G, Rangel S, et al. Pediatric emergency and essential surgical care in Zambian hospitals: a nationwide study. J Ped Surg. 2013;48:1363–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

URI;

URI;