Abstract

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is a rare form of ectopic pregnancy. Because CSP carries a high risk of uterine rupture and life-threatening bleeding, the pregnancy should be terminated upon confirmation of diagnosis. There have been few reports of CSP with successful delivery. We present a case of CSP under expectant management, with delivery via planned cesarean section at 35 weeks of gestation. This report suggests that successful pregnancy outcome can be achieved in some women with uterine cesarean scar, but further analysis and additional studies are required in order to describe the optimal protocol of expectant management in CSP.

Keywords: Cesarean scar pregnancy, Ectopic pregnancy, Expectant management, Placental invasion into myometrium, Hysterectomy

Highlights

-

•

Successful expectant management of CSP

-

•

Successful outcome can be achieved in CSP by frequent ultrasonography evaluation.

-

•

CSP is frequently complicated by placenta accreta.

1. Introduction

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is a form of ectopic pregnancy. CSP accounts for 6.1% of ectopic pregnancies, and 0.15% of pregnancies in which the patient had previously undergone a cesarean section. Selective abortion is typically recommended in CSP, and several treatment approaches have been reported [1]. There were few reports of successful CSP pregnancy. Herein, we report a case of CSP that was not terminated in the first trimester because of the couple's strong desire to have the baby. The outcome was viable birth after a 35-week gestation.

2. Case Report

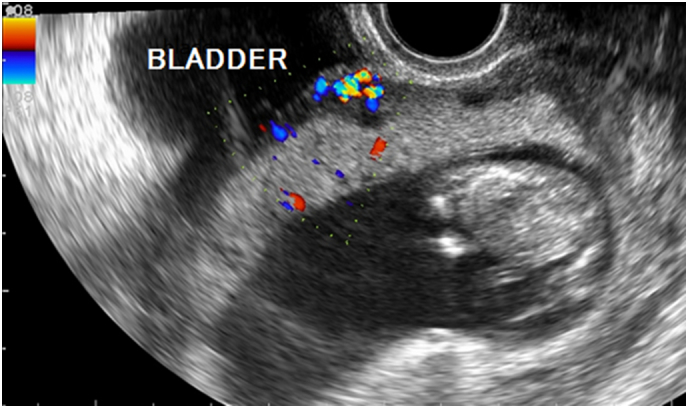

A 32-year-old gravida 3, para 3 (all cesarean) woman who attended another hospital for conception was referred to our hospital at 11 weeks of gestation after transvaginal ultrasound revealed a gestational sac fixed within a cesarean scar in the lower uterine segment. The patient presented to our hospital at 12 weeks and 5 days of gestation, with a suspicion of CSP. Transvaginal ultrasound revealed a gestational sac embedded within the anterior lower segment of the cesarean scar; empty uterine cavity and cervix; and thinned myometrium between the placenta and bladder (Fig. 1). After being informed of the ectopic nature of CSP and the very high risk for obstetrical bleeding and uterine rupture, the couple chose to continue the pregnancy despite our recommendation to terminate.

Fig. 1.

Ultrasonographic image at 12 weeks and 5 days of gestation shows the gestational sac embedded within the anterior lower segment of the cesarean scar, and overswelling of multiple vessels between the placenta and the bladder.

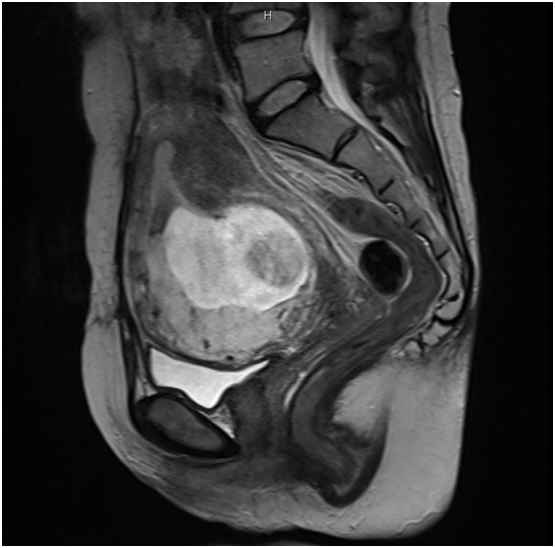

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 14 weeks and 1 day of gestation also suggested CSP, showing overswelling in multiple vessels at the edge of the placenta, and thinned myometrium between the placenta and the bladder. Moreover, the placenta seemed to have penetrated into the bladder wall, suggesting placenta percreta (Fig. 2). The cystoscopy at 19 weeks and 2 days of gestation showed no obvious vascular invasion to the mucosa of the urinary bladder.

Fig. 2.

MRI image at 14 weeks and 1 day of gestation shows the placenta penetrating into the muscle of the bladder wall.

Thereafter, the pregnancy continued without significant complications, as the placenta gradually migrated to the upper segment of the uterus. Although the cesarean scar became thinner, the degree of penetration of the placenta into the bladder wall muscle did not increase, as shown by MRI at 32 weeks and 2 days of gestation.

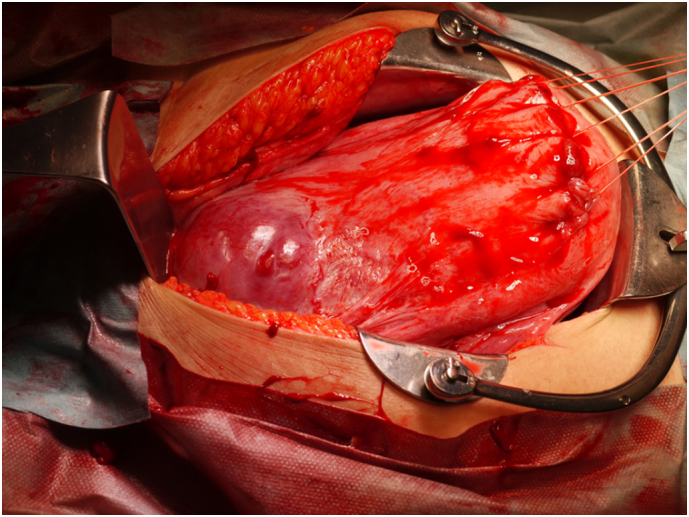

The delivery date was set to after 34 weeks of gestation, to allow maturation of the lungs. The patient underwent cesarean section at 35 weeks and 2 days of gestation, giving birth to a healthy female neonate with 2100 g of birth weight. Hysterectomy was performed during cesarean section because placental invasion into the myometrium was observed, with multiple vessels from the myometrium to the bladder (Fig. 3). Total blood loss during cesarean hysterectomy was 3445 ml, and the patient received transfusion with 6 and 2 units of red cell concentrate and autologous blood, respectively. The 1- and 5-min Apgar scores were 7 and 8, respectively, and umbilical blood pH was 7.351. Histopathology showed placenta increta, with chorionic villi invading the myometrium, but not penetrating through it. The patient and the baby, respectively, were discharged at 7 and 38 days postoperatively, with no complications.

Fig. 3.

Cesarean section in a woman with cesarean scar pregnancy. Placental invasion into the myometrium was observed, and hysterectomy was performed after removing the neonate.

3. Discussion

CSP diagnosis is based on finding a gestational sac at the site of previous cesarean sections, with empty uterine cavity and cervix, and thin myometrium adjacent to the bladder [2]. While CSP is often diagnosed at 7–8 weeks of gestation, the patient in the present report was diagnosed at 12 weeks, with the original suspicion at 11 weeks. CSP is typically terminated upon confirmation of diagnosis to avoid life-threatening complications [3]. However, we surveyed 36 cases (Table 1) of CSP that continued under expectant management [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. Because of genital bleeding, hysterectomy was performed in the second trimester in 10 cases. Live offspring were delivered in 26 cases, at 26–39 weeks of gestation. Hysterectomy was performed at delivery in 17 cases.

Table 1.

Cesarean scar pregnancy continued under expectant management.

| Reference | Number of cases | Hysterectomy in the second trimester | Live offspring | Gestational age (weeks) at delivery | Hysterectomy at delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herman et al., 1995 [4] | 1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 35 | 1/1 |

| Ben Nagi et al., 2005 [5] | 1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 37 | 1/1 |

| Wong et al., 2005 [6] | 1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 37 | 1/1 |

| Jurkovic et al., 2007 [7] | 2 | 1/2 | 1/1 | Unclear | 1/1 |

| Abraham et al., 2012 [8] | 1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 28 | 1/1 |

| Sinha et al., 2012 [9] | 1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 37 | 1/1 |

| Cheng et al., 2014 [10] | 2 | 0/2 | 2/2 | At term | 0/2 |

| Timor-Tritsch et al., 2015 [11] | 10 | 6/10 | 4/10 | 32–36 | 3/4 |

| Michaels et al., 2015 [12] | 8 | 3/8 | 5/8 | 29–39 | 3/5 |

| Zosmer et al., 2015 [13] | 9 | 0/9 | 9/9 | 26–38 | 5/9 |

| Total | 36 | 10/36 (27.8%) | 26/36 (72.2%) | 26–39 | 17/26 (65.4%) |

There are two different types of CSP. In type 1, the embryo progresses towards the uterine cavity, and, despite the high risk of massive bleeding and placenta accrete, live birth may occur. In type 2, pregnancy must be terminated immediately because the embryo embeds deep within the cesarean scar and grows towards the bladder and abdominal cavity, often causing uterine rupture and intraperitoneal haemorrhage [14]. In the case reported here, the amniotic cavity developed progressively towards the body of the uterus, suggesting type 1 CSP, and allowing live birth under strict expectant management.

Further analysis and additional studies are required in order to describe the optimal protocol of expectant management in CSP.

Conflicts of Interest

Shoko Tamada, Hisashi Masuyama, Jota Maki, Takeshi Eguchi, Takashi Metsui, Eriko Eto, Kei Hayata, and Yuji Hiramatsu declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Birch Petersen K., Hoffmann E., Rifbjerg Larsen C. Cesarean scar pregnancy: a systematic review of treatment studies. Fertil. Steril. 2015;105:958–967. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.12.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timor-Tritsch I.E., Monteagudo A., Santos R. The diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of cesarean scar pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;207(44):e1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y., Gu Y., Wang J.M. Analysis of cases with cesarean scar pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2013;39:195–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herman A., Weinraub Z., Avrech O. Follow up and outcome of isthmic pregnancy located in a previous Cesarean section scar. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1995;102:839–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb10855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben Nagi J., Ofili-Yebovi D., Marsh M. First-trimester cesarean scar pregnancy evolving into placenta previa/accreta at term. J. Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:1569–1573. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.11.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong H.S., Zuccollo J., Tait J. Placenta accreta in the first trimester of pregnancy: sonographic findings. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2009;37:100–103. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jurkovic D., Ben-Nagi J., Ofilli-Yebovi D. Efficacy of Shirodkar cervical suture in securing hemostasis following surgical evacuation of Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2007;30:95–100. doi: 10.1002/uog.4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham R.J., Weston M.J. Expectant management of a Cesarean scar pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012;32:695–696. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2012.703263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinha P., Mishra M. Cesarean scar pregnancy: a precursor of placenta percreta/accrete. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012;32:621–623. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2012.698665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng L.Y., Wang C.B., Chu L.C. Outcomes of primary surgical evacuation during the first trimester in different types of implantation in women with cesarean scar pregnancy. Fertil. Steril. 2014;102:1085–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.07.003. (e2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timor-Tritsch I.E., Khatib N., Monteagudo A. Cesarean scar pregnancies: experience of 60 cases. J. Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:601–610. doi: 10.7863/ultra.34.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michaels A.Y., Washburn E.E., Pocius K.D. Outcome of cesarean scar pregnancies diagnosed sonographically in the first trimester. J. Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:595–599. doi: 10.7863/ultra.34.4.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zosmer N., Fuller J., Shaikh H. Natural history of early first trimester pregnancies implanted in Cesarean scars. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;46:367–375. doi: 10.1002/uog.14775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vial Y., Petignat P., Hohlfeld P. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2000;16:592–593. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00300-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]