Abstract

Background

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) is a noninvasive method enabling excellent visualization of the small bowel (SB) mucosa. The aim of this study was to examine the impact and safety of VCE performed in children and adolescents with suspected or established Crohn’s disease (CD).

Methods

A total of 180 VCE examinations in 169 consecutive patients conducted in 2003–14 in a single center were retrospectively analyzed. The median age was 13 years (range 3–17 years) and indications for VCE were suspected (125 cases, 69%) and established (55 cases, 31%) CD. VCE was performed with a PillCam SB (Given Imaging, Yokneam, Israel) VCE system with 8–12 h of registration without bowel preparation.

Results

A total of 154 of 180 (86%) patients swallowed the capsule and 26 (14%) had the capsule endoscopically placed in the duodenum. Patency capsule examination was performed in 71 cases prior to VCE to exclude SB obstruction. VCE detected findings consistent with SB CD in 71 (40%) examinations and 17 (9%) procedures showed minor changes not diagnostic for CD. A total of 92 (51%) examinations displayed normal SB mucosa. The capsule did not reach the colon within the recording time in 30 (17%) procedures and were defined as incomplete examinations. A change in diagnosis or therapy was recommended in 56 (31%) patients based on VCE results. Capsule retention occurred in one patient.

Conclusions

VCE is a safe method in children with suspected or established CD. VCE often leads to a definitive diagnosis and has a significant impact on the clinical management of pediatric patients with CD.

Keywords: capsule endoscopy, children, Crohn’s disease, small bowel

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic relapsing inflammation in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of unknown etiology. In children and adolescents, CD is especially insidious because of the negative influence of pathological inflammation in the small bowel (SB) on nutrition, resulting in growth and development retardation.1 Most patients with CD have some extent of SB engagement and up to one third suffer from inflammation limited to the SB.2,3 Moreover, the onset of CD is located in the SB in more than 20% of pediatric patients.4,5 However, these estimates are somewhat uncertain because they are based on outdated methods to examine the SB, which might have underestimated the extent of inflammation in the SB. One important question is whether information about more proximal SB disease in addition to what is observed using standard endoscopic and imaging evaluations would change therapeutic strategies.

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) is a noninvasive method enabling excellent visualization of the SB mucosa.6–8 In fact, since its introduction in 2001, VCE has become the preferred method for evaluation of obscure GI bleeding, tumors and inflammation in the SB.9–13 Several studies have documented that VCE effectively detects CD in adult patients. For example, one study reported 20% increased diagnostic yield of SB CD lesions compared with ileoscopy14 and another investigation showed that VCE is superior in detecting mucosal lesions compared with magnetic resonance enterography (MRE).15 However, the impact of VCE on the clinical management of pediatric patients with CD has not been evaluated in large single-center studies.16 Thus, the aim of this study was to examine the impact and safety of VCE performed in children and adolescents being investigated for suspected and established CD in a large sample of patients from one tertiary center for pediatric VCE.

Materials and methods

Patients

This retrospective study evaluated all consecutive pediatric patients with suspected or known CD undergoing VCE from October 2003 to December 2014 at Skåne University Hospital in Malmö, Sweden. All patients gave written informed consent prior to VCE examinations. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Lund University, Sweden (582/2006, 412/2016). The medical records of patients were analyzed by an experienced gastroenterologist before VCE to identify patients with potential SB obstruction. Patients with suspected SB stricture underwent patency capsule (PC) examination. In the case of SB patency, patients continued with VCE. Patients treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs within a period of 6 months before VCE were excluded.

Video capsule endoscopy

VCE examinations were performed with the PillCam SB1, SB2 and SB3 VCE system (Given Imaging Ltd, Yokneam, Israel) after an 8 h fast without any bowel preparation. After swallowing the capsule, patients were allowed clear liquids after 2 h and solid food after 4 h. If a patient was not able to swallow the capsule the VCE delivery device (AdvanCE, US Endoscopy, Mentor, OH, USA) or the Roth Net retrieval device (US Endoscopy) was used for capsule deployment via a gastroscope in the duodenum. All VCE examinations were evaluated by one of four gastroenterologists having experience with VCE. No further controls were done if the video showed capsule passage to the colon. An abdominal x-ray film was recommended 2 weeks after VCE if the video did now show capsule passage to the colon or if the patient did not observe natural passage of the capsule.

Patency capsule

PC examinations were performed using a first- or a second-generation PC. A PC test was considered negative if the capsule was eliminated from the GI tract within 40 h (first-generation PC) or 30 h (second-generation PC) from ingestion according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Elimination of the PC was confirmed using a handheld scanner.

Definitions

Patients referred for VCE with symptoms of abdominal pain or diarrhea were categorized as having suspected CD if they fulfilled the International Conference on Capsule Endoscopy (ICCE) criteria, or if their referring physician suspected CD.17 Patients were diagnosed as having CD if they were treated for CD on the basis of their symptoms and additional objective findings. VCE consistent with CD was defined as the presence of more than three erosions and ulcerations in the SB while three or fewer SB lesions was defined as suspected but not diagnostic for CD.18

Results

A total of 180 VCE examinations were performed in 169 consecutive patients. Patients had a median age of 13 years with a range from 3 to 17 years. Twenty-three (13%) patients were younger than 10 years. A majority of patients (154, 86%) swallowed the capsule and 26 (14%) had it delivered endoscopically into the duodenum. The median age of patients requiring endoscopic placement of the capsule was 9 years while those who swallowed the capsule were on average 14 years old. In 30 of 180 (17%) procedures the capsule did not reach the colon during the recording time and were defined as incomplete examinations, as shown in Table 1. Of these incomplete cases, 11 (37%) capsules were placed endoscopically into the duodenum. Findings consistent with CD were found in 13 (43%) of the 30 incomplete studies. The capsule showed SB mucosa for more than 7 h (range 3–11 h) in incomplete procedures. The majority of patients with incomplete examinations swallowed the SB1 capsule, with 20 (67%) cases having only 8 h of recording time, while 8 (27%) incomplete procedures were conducted with the SB2 capsule having a maximum of 9 h of recording time. Only 2 of 30 incomplete studies (7%) were performed with the SB3 capsule, which has 12 h of recording time and these two capsules had been endoscopically placed in the duodenum.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 180).

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age and sex | |

| Median age (range), years | 13 (3–18) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 81 (45) |

| Crohn’s disease, n (%) | |

| Suspected | 125 (69) |

| Established | 55 (31) |

| Delivery of capsule, n (%) | |

| Swallowed by the patients | 154 (86) |

| Endoscopic placement | 26 (14) |

| Completeness of VCE, n (%) | |

| Complete | 150 (83) |

| Incomplete | 30 (17) |

VCE, video capsule endoscopy.

Indications for VCE were suspected CD in 125 (69%) cases and established CD in 55 (31%) procedures. VCE detected mucosal abnormalities in 98 (54%) examinations whereas SB findings were observed in 88 (49%) studies. Seventy-one of these 88 (81%) cases were consistent with CD (Figure 1) and 17 (19%) procedures showed minor changes not diagnostic for CD. A total of 92 (51%) studies displayed normal SB mucosa. Colonic lesions were seen in 14 (8%) examinations, including 10 cases in which no SB findings were concomitantly detected. VCE showed previously unidentified lesions in the colon in three studies. In patients with established CD, 44 of 55 (80%) examinations showed findings consistent with SB CD, whereas 10 (18%) cases were negative and only a single patient had nonspecific abnormalities. Twenty-nine of 55 (53%) procedures identified CD lesions in the jejunum. In the group of 125 suspected CD, a new diagnosis was made in 30 (24%) patients and CD was excluded in 79 (63%). Sixteen (13%) of these procedures showed SB lesions suggestive but not diagnostic for CD according to accepted criteria.18 The capsule showed CD in the jejunum in 17 of the 125 (14%) suspected cases.

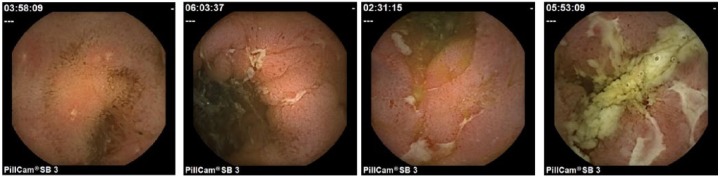

Figure 1A–D.

Video capsule endoscopy images showing mucosal inflammation and ulcerations consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.

A new diagnosis or a change in therapy occurred in 56 (31%) patients. Fifty-three patients had SB findings and three had previously unidentified CD lesions in the colon. We detected 71 cases showing Crohn lesions in the SB, and as a result of VCE findings, a change in therapeutic management was recommended in 47 (66%) of these patients with CD. Therapeutic changes included intensification or initiation of anti-inflammatory treatment in 43 (60%) patients; therapy was decreased in 2 (3%) patients and 2 (3%) patients refused recommended treatment. Biologic medication was started in 19 (27%) and immunomodulatory treatment was initiated in 14 (20%) of these 71 patients. Surgical intervention was not suggested to any patient. The recommended therapeutic changes based on VCE results are described in detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Therapeutic changes stratified by VCE results in CD.

| VCE findings (n = 180) | Change not recommender, n (%) | Change recommended, n (%) | Biologic started, n (%) | IMM starts, n (%) | Steroids, n (%) | Medication decreased, n (%) | Other*, n (%) | Patient refused change, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal or nonspecific findings (109) | 105 (96) | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Consistent with CD (71) | 24 (34) | 47 (66) | 19 (27) | 14 (20) | 7 (10) | 2 (3) | 3 (4) | 2 (3) |

5-aminosalicylic acid, antibiotics.

CD, Crohn’s disease; IMM, immunomodulatory, VCE, video capsule endoscopy.

PC was used in 71 patients to identify those with potential SB obstruction before VCE. In 33 (46%) patients, PC examination did not demonstrate SB patency. In 14 (42%) of these cases, radiological imaging was performed and showed no SB stenosis but only 7 of these patients underwent subsequent VCE. Radiological examination showed SB stenosis in 8 (24%) cases and VCE was not performed. Seven (21%) patients without SB patency did not undergo further examinations. In four additional patients, cross-sectional imaging was not performed, but after repeated evaluation of the patient’s symptoms VCE was offered. In 38 (54%) cases, SB patency was confirmed and VCE was performed. Patients with endoscopic placement of the capsule and suspected SB obstruction underwent MRE to prove SB patency. We observed one case of capsule retention in the GI tract. In this patient, the capsule was retained within a metallic stent in the sigmoid colon which had been inserted previously to manage a CD stricture. The patient recovered after sigmoid resection.

Discussion

It is generally accepted that VCE is the method of choice to investigate SB mucosa in adults with various indications, including CD.10,13,19 In this large single-center retrospective pediatric cohort, it was found that VCE is safe and has an important impact on clinical management of pediatric patients with suspected and established CD. Only one case of capsule retention was noted, indicating that the procedure is safe in children at least after 3 years of age. Moreover, nearly half of the performed VCEs revealed abnormal intestinal findings and resulted in changes in therapy in 6 out of 10 of these patients, which suggests a benefit of performing an additional investigation with VCE in children with potential SB disease.

Two previous large single-center pediatric studies included patients up to 23 years and they did not focus on the impact of VCE on management of CD.7,20 All patients in our large European cohort were under 18 years old. Herein, we found a 49% detection rate of Crohn lesions in the SB, which is similar to previous studies.8,20 Moreover, a majority (81%) of the SB findings were diagnostic for CD. At the same time, VCE excluded SB CD in about 51% of the cases, which is of great importance for further management of CD. Most of the children were able to swallow the capsule and the capsule reached the colon during the recording time in the majority of the examinations. The rate of incomplete procedures (17%) compares well with other studies, ranging from 21% to 23%.7,20,21 Notably, 42% of the capsules deployed endoscopically in the duodenum did not reach the colon during recording time. The longer SB transit time might be related to the use of general anesthesia and endoscopic placement of the capsule in the incomplete studies.22 Nonetheless, the SB was visualized in all incomplete studies. Interestingly, CD was diagnosed more often (43%) in patients with incomplete procedures than those with complete examinations (38%), indicating that incomplete VCE examinations do not hamper diagnostic yield. The explanation could be that in incomplete procedures the capsule still spends on average more than 7 h examining SB even if not reaching the cecum during recording time.

Although there is some evidence to prepare the bowel prior to SB VCE, optimal bowel preparation is controversial.23 A current meta-analysis of adult studies demonstrated that laxatives do not improve diagnostic yield or completion rate in SB VCE, although SB visualization is improved. That meta-analysis concluded that the use of laxatives might be beneficial in patients likely to have subtle findings.24 The only prospective pediatric study to date supports the use of 25 ml/kg (up to 1000 ml/day) of polyethylene glycol solution plus 20 ml (376 mg) of oral simethicone as the preparation of choice for VCE. This study demonstrated that despite improvement in mucosal visualization, there was not a significant difference in the overall diagnostic yield between the study groups.25 In our study, we performed VCE without bowel preparation and SB cleanliness grading because Crohn lesions in the SB are often multiple and missing minor mucosal changes does not affect diagnostic yield of VCE. Furthermore, bowel preparation might increase patient discomfort and decrease compliance in children.

MRE examinations have a tendency to miss the diagnosis of CD in the jejunum.26 In our study, VCE showed significant inflammatory activity in the jejunum in more than 25% of all examinations, indicating the importance of VCE in the workup of patients with CD. It should be emphasized that jejunal CD lesions were detected in more than half of the patients with established CD in our study.

Our study shows that VCE is a safe method in pediatric patients with established and suspected CD. In fact, we found a very low complication frequency with a capsule retention rate of only 0.6% (one case), which is lower than that observed in most other studies, ranging from 1.0% to 4.9%.7,20,21,27 This case of capsule retention was special in the sense that the capsule was retained in a metallic stent.28 Thus, previous stenting in the GI tract should be taken into consideration before performing VCE. Notably, we did not observe any capsule retention in the SB, which is in line with a previous prospective study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease.29 The use of PC in adults has been shown to decrease the risk of capsule retention.30 In our sample, 46% of PC examinations did not suggest SB patency. This high proportion could be explained by the fact that elimination of PC was confirmed using a handheld scanner and some of the PC could have been in the colon at the time of scanning. One study reported that use of PC is a useful screening tool in adolescents,31 but it is controversial whether younger children should undergo PC examination because they cannot swallow the PC and sedation solely for endoscopic deployment of PC is not recommended.32 At the same time, several studies have shown that radiological SB imaging, such as barium SB follow through, computed tomographic enteroclysis and magnetic resonance enteroclysis does not exclude SB stenosis.30,32 Our low capsule retention rate can be explained by careful patient selection with frequent use of PC in patients older than 10 years.

Conclusion

This study in a large cohort of pediatric patients demonstrates that VCE has a significant clinical impact on the management of children and adolescents with suspected and established CD. Additionally, VCE was associated with an exceptionally low capsule retention rate in the GI tract.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: G.W. Johansson and E. Toth received lecture fees from Given Imaging/Medtronic.

Funding: A. Nemeth received a grant for PhD students from Region Skåne.

ORCID iD: Ervin Toth  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9314-9239

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9314-9239

Contributor Information

Artur Nemeth, Department of Gastroenterology, Skåne University Hospital, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden.

Daniel Agardh, Department of Pediatrics, Skåne University Hospital, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden.

Gabriele Wurm Johansson, Department of Gastroenterology, Skåne University Hospital, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden.

Henrik Thorlacius, Department of Surgery, Skåne University Hospital, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden.

Ervin Toth, Endoscopy Unit, Department of Gastroenterology, Skåne University Hospital, Lund University, Getg, 40, S-205 02 Malmö, Sweden.

References

- 1. Oliveira SB, Monteiro IM. Diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease in children. BMJ 2017; 357: j2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2011; 140: 1785–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, et al. A simple classification of Crohn’s disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2000; 6: 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chouraki V, Savoye G, Dauchet L, et al. The changing pattern of Crohn’s disease incidence in northern France: a continuing increase in the 10- to 19-year-old age bracket (1988–2007). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 33: 1133–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cuffari C, Dubinsky M, Darbari A, et al. Crohn’s jejunoileitis: the pediatrician’s perspective on diagnosis and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005; 11: 696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature 2000; 405: 417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jensen MK, Tipnis NA, Bajorunaite R, et al. Capsule endoscopy performed across the pediatric age range: indications, incomplete studies, and utility in management of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomson M, Fritscher-Ravens A, Mylonaki M, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy in children: a study to assess diagnostic yield in small bowel disease in paediatric patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007; 44: 192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cavallo D, Ballardini G, Ferrari A, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy in adolescents with familial adenomatous polyposis. Tumori 2016; 102: 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eliakim R. The impact of panenteric capsule endoscopy on the management of Crohn’s disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2017; 10: 737–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kopylov U, Seidman EG. Clinical applications of small bowel capsule endoscopy. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2013; 6: 129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leighton JA, Gralnek IM, Cohen SA, et al. Capsule endoscopy is superior to small-bowel follow-through and equivalent to ileocolonoscopy in suspected Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pennazio M, Spada C, Eliakim R, et al. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy 2015; 47: 352–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dionisio PM, Gurudu SR, Leighton JA, et al. Capsule endoscopy has a significantly higher diagnostic yield in patients with suspected and established small-bowel Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1240–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tillack C, Seiderer J, Brand S, et al. Correlation of magnetic resonance enteroclysis (MRE) and wireless capsule endoscopy (CE) in the diagnosis of small bowel lesions in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008; 14: 1219–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen SA, Klevens AI. Use of capsule endoscopy in diagnosis and management of pediatric patients, based on meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mergener K, Ponchon T, Gralnek I, et al. Literature review and recommendations for clinical application of small-bowel capsule endoscopy, based on a panel discussion by international experts. Consensus statements for small-bowel capsule endoscopy, 2006/2007. Endoscopy 2007; 39: 895–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tukey M, Pleskow D, Legnani P, et al. The utility of capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 2734–2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis 2017; 11: 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cohen SA, Ephrath H, Lewis JD, et al. Pediatric capsule endoscopy: review of the small bowel and patency capsules. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 54: 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nuutinen H, Kolho KL, Salminen P, et al. Capsule endoscopy in pediatric patients: technique and results in our first 100 consecutive children. Scand J Gastroenterol 2011; 46: 1138–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oikawa-Kawamoto M, Sogo T, Yamaguchi T, et al. Safety and utility of capsule endoscopy for infants and young children. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 8342–8348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ladas SD, Triantafyllou K, Spada C, et al. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE): recommendations (2009) on clinical use of video capsule endoscopy to investigate small-bowel, esophageal and colonic diseases. Endoscopy 2010; 42: 220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yung DE, Rondonotti E, Sykes C, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: is bowel preparation still necessary in small bowel capsule endoscopy? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 11: 979–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oliva S, Cucchiara S, Spada C, et al. Small bowel cleansing for capsule endoscopy in paediatric patients: a prospective randomized single-blind study. Dig Liver Dis 2014; 46: 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kopylov U, Yung DE, Engel T, et al. Diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy versus magnetic resonance enterography and small bowel contrast ultrasound in the evaluation of small bowel Crohn’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 2017; 49: 854–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Atay O, Mahajan L, Kay M, et al. Risk of capsule endoscope retention in pediatric patients: a large single-center experience and review of the literature. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009; 49: 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Toth E, Marthinsen L, Bergström M, et al. Colonic obstruction caused by video capsule entrapment in a metal stent. Ann Transl Med 2017; 5: 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Di Nardo G, Oliva S, Ferrari F, et al. Usefulness of wireless capsule endoscopy in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 43: 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nemeth A, Wurm Johansson G, Nielsen J, et al. Capsule retention related to small bowel capsule endoscopy: a large European single-center 10-year clinical experience. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2017; 5: 677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cohen SA, Gralnek IM, Ephrath H, et al. The use of a patency capsule in pediatric Crohn’s disease: a prospective evaluation. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56: 860–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Friedlander JA, Liu QY, Sahn B, et al. NASPGHAN capsule endoscopy clinical report. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017; 64: 485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]