Abstract

Since the sulfur specific cleavage is vital for the organic sulfur removal from fossil fuel, we explored potential bacterial strains of MTCC (Microbial Type Culture Collection) to desulfurize the Dibenzothiophene (DBT) through C-S bond cleavage (4-S pathway). MTCC strains Rhodococcus rhodochrous (3552), Arthrobacter sulfureus (3332), Gordonia rubropertincta (289), and Rhodococcus erythropolis (3951) capable of growing in 0.5 mM DBT were examined for their desulfurization ability. The presence of dsz genes as well as the metabolites was screened by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and HPLC, respectively. All these strains showed > 99% DBT desulfurization with 10 days of incubation in minimal salt medium. From the HPLC analysis it was further revealed that these MTCC strains show differences in the end metabolites and desulfurize DBT differently following a variation in the regular 4-S pathway. These findings are also well corroborating with their respective organization of dszABC operons and their relative abundance. The above MTCC strains are capable of desulfurizing DBT efficiently and hence can be explored for biodesulfurization of petrochemicals and coal with an eco-friendly and energy economical process.

Introduction

Energy is essential to life, and its central source comes from fossil fuels. The elemental fossil fuels used today by most industrialized and developing countries are oil, coal, and natural gas [1, 2]. Among these fossil fuels, sulfur is the major contaminant contributing towards environmental pollution as well as health hazards in the form of acid rain and sulfur oxide emissions [3]. The current scenario of escalating inclination in global energy exploitation is due to mounting world population leading to more energy consumption. As a result, the highly efficient low sulfur fossil fuels are depleting. Therefore, we have to master the efficiency of the high sulfur fossil fuels for a sustainable energy source in coming future. At the same time retaining restricted sulfur emission as per the stringent rules for pollution control, the need of appropriate desulfurizing technologies for high sulfur-containing fossil fuels has become crucial. Among various sulfur bearing compounds the most predominant form of sulfur is dibenzothiophene (DBT) and its derivatives in the petroleum and coal [4, 5] which is refractory to the contemporary desulfurization techniques.

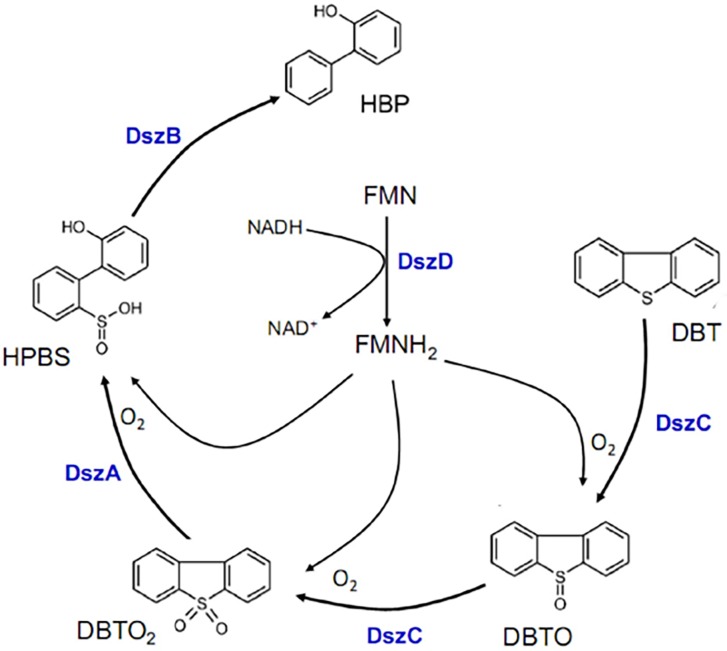

Biodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene and its derived compounds have caught global attention owing to unavailability of economic and eco-friendly techniques for the removal of organic sulfur unlike pyritic sulfur removal. Certain microorganisms have the ability to derive sulfur from complex organic sulfur compounds (like DBT) for their growth and vital activities, and hence can be exploited for organic sulfur removal in fossil fuels with minimal environmental impact [6]. Most of the reported strains oxidize sulfur in DBT by following 4-S pathway with the help of three enzymes, DBT monooxygenase (DszC), DBT sulfone monooxygensae (DszA) and 2-HBP desulfinase (DszB) supported by another enzyme flavin reductase (DszD) as presented in Fig 1 [7–9]. This sulfur specific pathway which does not interrupt the carbon skeleton and proceeds at normal physical conditions is governed by dszABC operon consequently making it an essential criterion for a potential biodesulfurizing candidate. Various strains like Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8, Rhodococcus sp. Eu-32, Gordonia alkanivorans RIPI 90A, Gordonia alkanivorans 1B, Actinomycete sp., Gordonia IITR having dszABC operon and dszD genes have been reported for biodesulfurization of DBT and its derivatives in last two decades [10–15]. However, not much attention has been paid to explore the differential biodesulfurization of DBT by bacterial strains with reference to the dszABC operon. Against this background, the present investigation has been designed to explore novel strains of Microbial Type Culture Collection (MTCC) containing dsz genes for their ability to desulfurize DBT and compare their end metabolites. This comparative study explains how the different metabolites of DBT are directly linked to the organization of dsz genes.

Fig 1. 4S-Pathway of biodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene (DBT).

Four enzymes (DszA, DzsB, DszC and DszD) are involved in the pathway where the first three steps catalyzed by flavin mononucleotide reduced (FMNH2)-dependent monooxygenases, those leading to DBT-sulfoxide (DBTO), DBT-dioxide (DBTO2) and hydroxyphenyl benzenesulfinate (HPBS), respectively. The final desulfurization step to 2-hydroxybiphenyl (2-HBP) is catalyzed by desulfinase.

It is also established that DBT enters into the bacterial cell and gets transformed into 2-HBP by the action of Dsz enzymes and finally released into the medium [16]. Therefore, in a liquid system like petroleum or oil, DBT is more easily available for the bacteria than that of coal, where DBT is covalently bound to the coal matrix [17]. Keeping these observations in mind we hypothesized that differential availability of free DBT in different sources is contributing for differential behavior of 4S-pathway which is central for the removal of organic sulfur from coal as well as oil without compromising the calorific value. To test this hypothesis, different MTCC strains were explored for desulfurization of DBT.

Materials and methods

Materials

Dibenzothiophene (DBT), 2-Hydroxybiphenyl (2-HBP) and glycerol were obtained from Sigma. HPLC grade of ethyl acetate was obtained from SRL. Beef extract, peptone and sodium chloride were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Yeast extract, ammonium chloride and agar were purchased from Hi-media. All Other chemicals were obtained from SRL.

In-silico approach for screening of organisms

Since Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 (Accession: L37363) has been extensively studied for biodesulfurization of DBT, the nucleotide sequences of R. erythropolis IGTS8 were retrieved from NCBI and explored to find novel biodesulfurizing strains using BLAST. A short sequence stretch 5’ aagtactaccaacacatcgcccgtactctggagcgcggcaagttcgatctgttgtttctg 3’ starting from 901 to 960 of the whole sequence which is part of the dszABC operon was used as a query sequence for nucleotide blast program. As an outcome, a list of organisms was obtained from the NCBI database which had dsz genes (Table 1). Database hits that had a higher score, expect value, identity (more than 85%) and query coverage (more than 65%) were taken as putative homolog.

Table 1. Possible bacterial strains containing dszABC operon.

| Sl. No. | Accession Number | Organism with dszABC operon |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | EF570781.1 | Synthetic construct |

| 2 | DQ444325.1 | Rhodococcus sp. DS-3 |

| 3 | AY789136.1 | Rhodococcus sp. SDUZAWQ |

| 4 | AY714059.1 | Nocardia globerula |

| 5 | AY714058.1 | Rhodococcus erythropolis |

| 6 | AY714057.1 | Gordonia alkanivorans |

| 7 | AY294402.1 | Rhodococcus erythropolis |

| 8 | AY278323.1 | Rhodococcus sp. XP |

| 9 | DQ062154.1 | Acidovorax delafieldii |

| 10 | DQ062161.1 | Brevibacillus brevis |

| 11 | AY960127.1 | Agrobacterium tumefaciens |

| 12 | AJ514948.1 | Rhodococcus sp. FMF |

| 13 | U08850.1 | Rhodococcus sp. |

| 14 | L37363.1 | Rhodococcus sp. |

| 15 | EU364831.1 | Gordonia alkanivorans |

| 16 | AJ973326.1 | Gordonia sp. RIPI |

| 17 | AB076745.1 | Bacillus subtilis |

| 18 | AY396519.1 | Gordonia sp. CYKS2 |

Selection of MTCC cultures

In continuation to the in-silico screening, MTCC strains Rhodococcus rhodochrous (3552), Rhodococcus erythropolis (3951), Arthrobacter sulfureus (3332), Brevibacillus brevis (6640), Brevibacillus laterosporous (2298), Gordonia alkanivorans (4014), Gordonia rubropertincta (289), Bacillus subtilis (1427), Bacillus subtilis (2422), and Acidovorax facilis (1198) belonging to seven different genera were selected based on their biochemical features (S1 Table) and procured from MTCC, Chandigarh, India). The selection of bacterial strains was based on the criteria that, the MTCC strains were of same genus and species as that of organisms obtained by the in-silico approach. Moreover, species that showed the presence of known characteristics like degradation of xenobiotics, phenolics, etc. were preferred. Source of isolation such as from coal mines or oil spill contaminated soil was also given emphasis while selecting novel MTCC strains.

Enrichment of MTCC culture with DBT

After the cultures were revived in the media prescribed by MTCC, they were grown in minimal salt medium (MSM) containing 2.44 g of KH2PO4, 14.04 g of Na2HPO4, 2.0 g of NH4Cl, 0.2 g of MgCl2, 2.5 mg of MnCl2, 1.0 mg of FeCl3, 1 mg of CaCl2, and 4 ml of glycerol in 1L of double distilled water (DDW) with pH 7.6 [18]. To check whether the organisms were able to uptake sulfur from DBT, we took sulfur-free MSM medium with different concentration of DBT 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mM. Desulfurizing strains growing with a higher concentration of DBT (0.5 mM) were selected for further study. These cultures were incubated for ten days and subjected to screening of dsz genes and desulfurizing assay.

Screening of dszA, dszB, dszC and dszD

Total DNA was isolated using a rapid protocol described in literature [19]. In brief, 100 μl of fresh culture was taken in duplicate and centrifuged at 6000xg for 3 min at 4°C. Supernatant containing media were carefully taken out using a pipette. Then 100 μl of autoclaved MilliQ water was added to the pellet, cells were resuspended, thoroughly mixed and incubated at 97°C for 10 min. Cell debris was removed by centrifuging at 10000xg for10 min, at 4°C. The supernatant containing DNA was taken for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Presence of desulfurizing genes viz. dszA, dszB, dszC, and dszD in different cultures were studied by PCR using a BioRad thermal cycler. Gene specific primer sequences from earlier reports were custom synthesized by Integrated DNA Technology, USA. The optimum annealing temperature was examined by taking five different temperatures for the amplification of different PCR product. Information on primers and PCR condition for different genes is given in S2 Table.

The PCR mixture of 25 μl included 0.5 μl total DNA as template, 2.5 μl 10x buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1U Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas), and 25 pmol of each primer. The mixture was then subjected to PCR with a cycle parameter; 95°C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30s, annealing for 30s, 72°C for 1.5 min and final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed on ethidium bromide stained 1.0% agarose gel and images were documented in Cell Biosciences Gel Documentation system. Selected PCR products were sequenced by direct genomic sequencing method for further studies.

Desulfurization of DBT and analysis of metabolites

Peaks of intermediate metabolites and 2-HBP of the desulfurization process of DBT were observed through HPLC. For the HPLC analysis, ten days old cultures were taken and metabolites were extracted with double the volume of ethyl acetate. The mixture was vigorously shaken in a separating funnel for extraction. After phase separation, lower phase containing the biomass was discarded. The top layer containing ethyl acetate with the organic compound was concentrated to about 0.5 ml to 1 ml by rotary evaporator. Both DBT and 2-HBP were quantified using HPLC (Waters) equipped with NOVA PAK C18 column at 260 nm. The mobile phase was 60% acetonitrile-water, and the flow rate was 1 ml min-1. A blank sample without bacterial extract was also analyzed through HPLC. Each sample was run for 30 minutes.

Phylogenetic analysis of dsz operon

Protein sequences for dsz operon genes from Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 were queried against NCBI nt-nr database for bacteria (taxid:2) using tblastn utility. A match was considered if match covers 60% of query sequence with E-value 1E-05 or less. Genes were considered in operonic structure if the gap between genes was 200 nt or less. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model created from MUSCLE facilitated multiple sequence alignment. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-3696.8650) is shown. The analysis involved 44 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 266 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.

Results and discussion

MTCC Cultures and enrichment with DBT

Though a diverse group of bacterial strains have been explored for the desulfurization studies still there is a need to identify more efficient organisms with enhanced desulfurizing ability [7]. In this context we tried to identify the potential microbes by using bioinformatics tools as an easy and quick approach. Initial strain selection was based on BLAST searches using a query sequence consisting of a short fragment of the dszABC operon against the NCBI database. Selection of strains from the MTCC was then based on similarity of genera names and previous phenotypic information that further indicated competency of strains with greater desulfurizing ability. Based on the in-silico criteria and special biochemical characteristics shown by the MTCC strains, around ten microbes from MTCC-IMTECH, Chandigarh (MTCC No. 3552, 3951, 3332, 289, 1198, 6640, 2298, 1427, 2422, and 4014) were used for the present investigation. For enriched culture, the media were supplemented with glycerol and various concentrations i.e. 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 mM of DBT. Since DBT was the only sulfur source, organisms that can utilize DBT for their growth would capable of desulfurization. As desired, MTCC 3552, 3951, 3332, and 289 strains were able to grow in 0.5 mM of DBT. DBT concentration reported for biodesulfurization was 0.1 mM [20] 0.2 mM [18], 0.5 mM [21], 0.8 mM [22] and 3 mM [23], hence the above strains growing in 0.5 mM DBT were used further for biodesulfurization study.

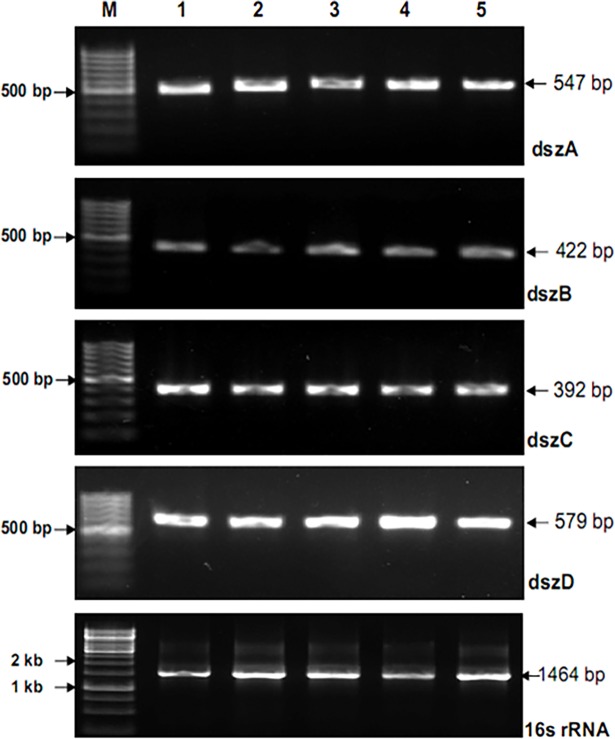

Amplification and screening of dsz genes

Amplification parameters of dsz genes were standardized and amplicons were as per expectation with no secondary products. Since the presence of dsz operon is a prerequisite for the BDS process in the 4S-pathway, potential MTCC cultures was screened for the presence of dsz genes. For this purpose, bacterial DNA of MTCC 3552, 3951, 3332, and 289 were used, and dsz genes were screened using gene specific primers (Fig 2). Amplification of 16S rRNA was also carried out as an internal standard present in all the bacteria. Interestingly, all the bands were visible in MTCC strains 3552 and 3332 suggesting both the organisms are capable of producing Dsz enzymes which proves highly conserved nature of dsz genes [21, 24]. In both the cases, the band intensity of amplified product of dszD is low as compared to dszA, dszB, and dszC (Fig 3). Nevertheless, the intensity of dszD in 3332 is lower as compared to 3552. Similar pattern was also observed with sample MTCC 289, but the intensity of dszC and dszD was much lower as compared to dszA and dszB (Fig 3). Interestingly with MTCC 3951 the PCR products of dszA and dszB were visible without dszC and dszD. Lack of the conserved sequences at the beginning of the dszC gene could be the explanation of the unsuccessful amplification of dszC [12]. From the dsz screening experiment it was observed that dszC and dszD are less abundant than dszA and dszB in the used strains. The partial sequences of dszA and dszB genes of strain 3552 and 3332 were aligned against the homologous sequences of reported strains using BIOEDIT graphic interface (S1 Fig). The strain MTCC 3552 shows 99% sequence identities and zero E value with strain Rhodococcus sp. DS-3 (genebank id DQ444325.1) and Norcadia globerula (genebank id AY714059.1) which are reported for biodesulfurization of diesel oil [24, 25], while MTCC 3332 shows 95% sequence similarity with the above strains (S1 Fig).

Fig 2. Standardization of PCR product of dsz genes and 16s rRNA with different annealing temperatures.

The PCR products with different annealing temperature were electrophoresed in agaraose gel against 100 bp DNA ladder.

Fig 3. Screening of dsz genes in different MTCC strains Rhodococcus rhodochrous (3552), Artrobacter sulfureus (3332), Gordonia rubropertincta (289) and Rhodococcus erythropolis (3951) enriched with DBT.

The different lanes are showing the amplified products of different genes dszA, dszB, dszC and dszD.

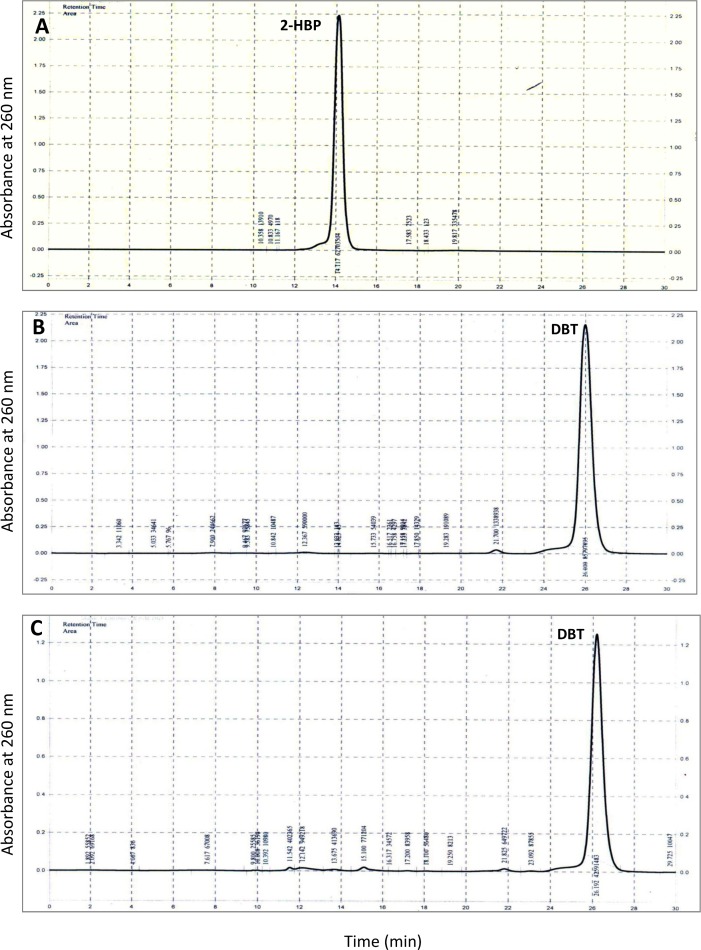

Desulfurization assay by HPLC

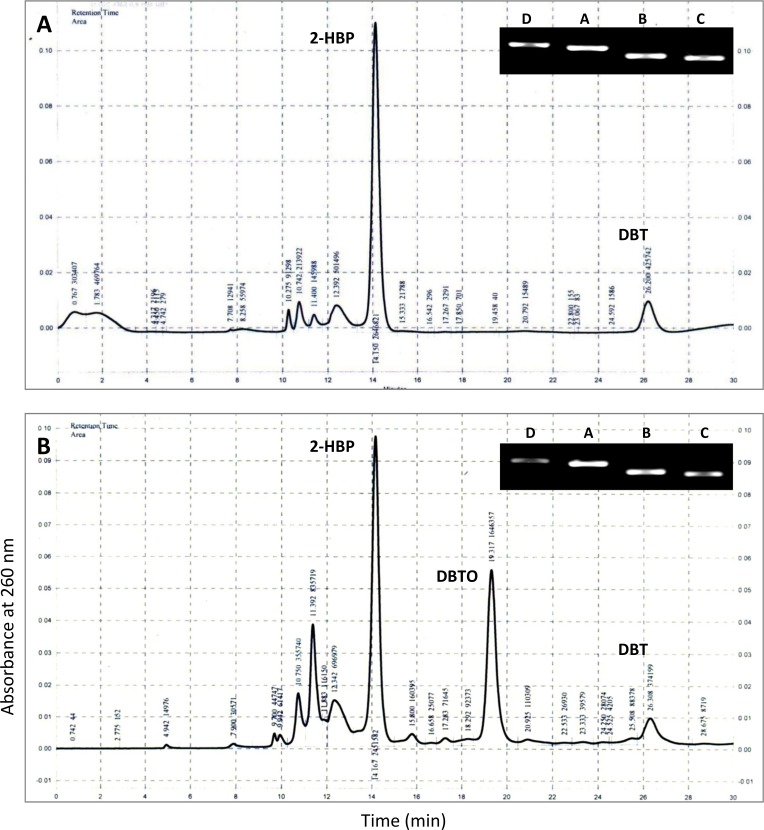

Since dszABC operon is central to the biodesulfurization process, it is imperative to understand how dsz genes operate in different organisms. With this background, four different MTCC strains (3552, 3951, 3332, and 289) containing dsz genes were explored for BDS of DBT and the end products were analyzed by HPLC. Both DBT and 2-HBP standards were prepared in ethyl acetate and injected for the generation of chromatogram. It was found that the retention time of 2-HBP and DBT is 14.125 min and 26.008 min respectively, at 260 nm (Fig 4A and 4B). A chromatogram of DBT (without any degradation) was obtained for the control sample which contained MSM supplemented with 0.5 mM DBT without any organism (Fig 4C). Chromatogram of respective samples were compared and found that the desulfurization of DBT was 98.9%, 99.26%, 99.4%, and 99.63% for strains Rhodococcus rhodochrous (3552), Artrobacter sulfureus (3332), Gordonia rubropertincta (289) and Rhodococcus erythropolis (3951) respectively (Fig 5). The most conspicuous observation was that except MTCC 289 all the other organisms showed the presence of 2-HBP, the end product of 4S-pathway. Moreover, a strong peak is appearing with retention time 1.742 min after biodesulfurization of DBT in case of MTCC 3951.

Fig 4.

HPLC graph showing the retention time of (a) DBT and (b) 2-HBP. (c) The control DBT without microorganism also shows same retention time with respect to the standard DBT without any degradation.

Fig 5.

Chromatogram showing the DBT desulfurization after 10 days of growth with different MTCC strains (a) Rhodococcus rhodochrous (3552), (b) Artrobacter sulfureus (3332), (c) Gordonia rubropertincta (289) and (d) Rhodococcus erythropolis (3951).

Reported experiments with several organisms along with the organisms used in the present studies with different rates of desulfurization of DBT are listed in Table 2. The strains MTCC 289, 3951, 3332 and 3552 are examined for the first time for BDS studies. Though strains like Gordonia alkanivorans with 90% desulfurization of DBT [26], and 70% desulfurization rate [27] has been reported previously but Gordonia rubropertincta (MTCC 289) of the present study is having a higher rate 99.4% of desulfurization. Similarly, the organism Rhodococcus erythropolis (MTCC 3951) in present study unlike other reported Rhodococcus erythropolis strains [21, 28, 29] shows variation in the regular 4S-pathway with a different end product other than 2-HBPS. The organism Arthrobacter sulfureus (MTCC 3332) however is showing similar pattern with that of 4-S pathway but with a higher desulfurization rate that is 99.3% than previously investigated Arthrobacter sulfureus species with 50% [30] and 83% [31] removal of sulfur. However, strain Rhodococcus rhodochrous (MTCC 3552) is showing similar biodesulfurization profile as reported in Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 [4, 32].

Table 2. List of organisms comparing their desulfurizing efficiency in percentage removal of sulfur from literature with reference to the present study.

| Reported Strains | Desulfurizing Efficiency | Days of Incubation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arthrobacter sulfureus | 50% | 15 | Labana et al. 2005 [30] |

| Lysinobacillus sphaericus | 60% | 15 | Bahuguna et al. 2011 [33] |

| Enterobacter spp. NISOC-03 | 64% | 10 | Papizadeh et al. 2016 [22] |

| Microbacterium strain ZD-M2 | 70% | 5 | Li et al. 2010 [25] |

| Gordonia alkanivorans 1B | 77% | 7 | Alves et al. 2008 [11] |

| Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 | 80% | 1 | Caro et al. 2007 [28] |

| Arthrobacter sp. P1-1 | 83% | 14 | Seo et al. 2006 [31] |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 | 88.5% | 10 | Gun et al. 2015 [20] |

| Gordonia alkanivorans RIPI90A | 90% | 10 | Mohebali et al. 2008 [26] |

| Rhodococcus rhodochrous (MTCC 3552) | 98.9% | 10 | This study |

| Arthrobacter sulfureus (MTCC 3332) | 99.26% | 10 | This study |

| Gordonia rubropertincta (MTCC 289) | 99.4% | 10 | This study |

| Rhodococcus erythropolis (MTCC 3951) | 99.6% | 10 | This study |

| Rhodococcus erythropolis SHT87 | 100% | 3 | Davoodi-deheghani 2010 [22] |

The desulfurization of DBT into 2-HBP by MTCC strains 3552 and 3332 is in accordance with previous findings such as Rhodococcus sp. [2, 18], Lysinibacillus sphaericus DMT-7 [33], and Pseudomonas sp. [34–36]. HPLC chromatogram for both DBT degradation and 2-HBP production is also alike. In addition to the 2-HBP peak in MTCC 3332 one prominent peak with retention time, 19.317 min was also observed. Nevertheless, this particular peak was very intense with the purified metabolites generated by strain MTCC 289 without any 2-HBP peak. Possibly this is an intermediate metabolite DBTO (Fig 1) accumulated in the bacterial cell. From the HPLC profile of MTCC 3951, we find less 2-HBP but the major product is coming with a retention time 1.742 min. However, it is worthy to mention that with 3951, the degradation of DBT was highest among all.

Phylogenetic analysis of dsz operon

The phylogenetic analysis reveals various candidate bacteria which contain the dsz operon and can be used in desulfurization process of petroleum and coal products (S2 Fig). Among the bacterial kingdom, the operon is predominantly observed in the species of Actinobacteria phylum. In this study also all the four MTCC strains belong to this phylum. However, the infrequent distribution of the dsz operon in Proteobacteria and Firmicutes phyla advocates for the scattered pattern of conservation of dsz genes suggesting horizontal gene transfer as a potential mode of origin of the operon. This observation is well corroborated with the phyolgenetic analysis of 16s rRNA sequences and deduced aminoacid sequences of dsz genes of previously reported strain Rhodococcus sps [13]. In the current study, the absence or faint bands of dszC and dszD suggests variation in the conserved sequences in the dsz operon structure. Different intermediate and end products warrants for the divergent evolution of dsz genes by strains isolated from different sources. To test our hypothesis we further investigated MTCC strains which were able to desulfurize free-DBT for the BDS of Assam coal which has high organic sulfur [5]. In support of our hypothesis, we could not get any significant desulfurization by these strains (Data not shown). This experiment clearly indicates that though organisms are capable of desulfurizing free-DBT, the coal desulfurization is not mimicking the process. Moreover, a comparative analysis of dsz genes, regulatory regions and the respective enzymes of different strains can offer insights regarding bacterial desulfurization at molecular level.

Conclusions

Present study reports for the first time the exploration of MTCC strains for biodesulfurization of DBT. The results showed that strains 3552, 3332, 289, and 3951 containing dsz genes are able to desulfurize > 99% DBT. Higher degree of sequence homology of the partial sequences of MTCC 3552 and MTCC 3332 and the HPLC profile of culture extracts well supported with the 4S-pathway reported in strains Rhodococcus erythropolis DS3 and Norcadia globerula for desulfurization of diesel and other model oil. Hence, they could be potentially explored for BDS of petrochemicals with different physiological parameters for an improved desulfurization of petroleum derivatives and oil with an advantageous green complementary approach towards low sulfur fossil-fuels. Further studies can infer regarding application of these strains for a sustainable process designing to meet the interminably growing energy demands at the same time maintaining the environmental strictures.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Out of ten organisms Rhodococcus rhodochrous (3552), Artrobacter sulfureus (3332), Gordonia rubropertincta (289) and Rhodococcus erythropolis (3951) were explored for the biodesulfurization study. All these strains were thoroughly characterized with following biochemical features and maintained in the MTCC, Chandigarh.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

MMB is grateful to the University Grants Commission, Government of India for granting fellowship. Thanks to Dr Prabhat M. Mishra of CSIR-Institute of Minerals & Materials Technology for helping in HPLC analysis and Dr Debasis Dash of CSIR-Institute of Genomics & Integrative Biology for Phylogenetic analysis.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by Ministry of Steel, government of India, GAP-220.

References

- 1.Alves L., Paixao S.M., Pacheco R., Ferreira A.F., Silva C.M., Biodesulphurization of fossil fuels: energy, emissions and cost analysis, RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 34047–34057. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohebali G., Ball A.S., Biodesulfurization of diesel fuels–Past, present and future perspectives. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation. 110 (2016) 163–180. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordoloi N.K., Bhagowati P., Chaudhuri M.K., Mukherjee A.K., Proteomics and Metabolomics Analyses to Elucidate the Desulfurization Pathway of Chelatococcus sp., PLoS One. 11 (2016) e0153547 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishra S., Panda P.P., Pradhan N., Satpathy D., Subudhi U., Biswal S.K., et al. , Effect of native bacteria Sinomonas flava 1C and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans on desulfurization of Meghalaya coal and its combustion properties. Fuel 117 (2014) 415–421. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra S., Pradhan N., Panda S., Akcil A., Biodegradation of dibenzothiophene and its application in the production of clean coal. Fuel Processing Technol. 152 (2016) 325–342. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmi F., Etemadifar Z., Emtiazi G.A., Novel metabolite (1,3-benzenediol, 5-hexyl) production by Exophiala spinifera strain FM through dibenzothiophene desulfurization, World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31 (2015) 813–821. doi: 10.1007/s11274-015-1835-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buzanello E.B., Rezende R.P., Sousa F.M.O., de Lima S.M., Loguercio L.L., A novel Bacillus pumilus-related strain from tropical landfarm soil is capable of rapid dibenzothiophene degradation and biodesulfurization, BMC Microbiol. 14 (2014) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray K.A., Pogrebinsky G., Mrachko T., Xi L., Monticello D.J., Squires C.H., Molecular mechanisms of biocatalytic desulfurization of fossil fuels, Nat Biotechnol. 4 (1996) 1705–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhasarkar J.B., Dikshit P.K., Moholkar V.S., Ultrasound assisted biodesulfurization of liquid fuel using free and immobilized cells of Rhodococcus rhodochrous MTCC 3552: A mechanistic investigation, Bioresour. Technol. 187 (2015) 369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.03.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piddington C.S., Kovacevich B.R., Rambosek J., Sequence and molecular characterization of a DNA region encoding the dibenzothiophene desulfurization operon of Rhodococcus sp. strain IGTS8., Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61 (1995) 468–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alves L., Melo M., Mendonça D., Simões F., Matos J., Tenreiro R., et al. , Sequencing, cloning and expression of the dsz genes required for dibenzothiophene sulfone desulfurization from Gordonia alkanivorans strain 1B, Enzyme Microb. Technol. 40 (2007) 1598–1603. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shavandi M., Sadeghizadeh M., Khajeh K., Mohebali G., Zomorodipour A., Genomic structure and promoter analysis of the Dsz operon for dibenzothiophene biodesulfurization from Gordonia alkanivorans RIPI90A, Appl. Gen. Mol. Biotechnol. 87 (2010) 1455–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhtar N., Ghauri M., Anwar M., Heaphy S., Phylogenetic characterization and novelty of organic sulphur metabolizing genes of Rhodococcus spp. (Eu-32), Biotechnol. Lett. 37 (2015) 837–847. doi: 10.1007/s10529-014-1736-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khedkar S., Shanker R., Isolation and classification of a soil actinomycete capable of sulphur-specific biotransformation of dibenzothiophene, benzothiophene and thianthrene, J. Appl. Microbiol. 118 (2015) 62–74. doi: 10.1111/jam.12665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karimi E., Jeffryes C., Yazdian F., Sepahi A.A., Hatamian A., Rasekh B., et al. , DBT desulfurization by decorating Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 using magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles in a bioreactor. Eng. Life Sci. 17 (2017) 528–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abin-Fuentes A., Leung J.C., Mohamed M.E.S, Wang D.I.C., Prather K.L.J., Rate-limiting step analysis of the microbial desulfurization of dibenzothiophene in a model oil system, Biotechnol. Bioeng., 111 (2014) 876–884. doi: 10.1002/bit.25148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marinov S.P., Gonsalvesh L., Stefanova M., Yperman J., Carleer R., Reggers G., et al. , Combustion behaviour of some biodesulphurized coals assessed by TGA/DTA, Thermochim. Acta. 497 (2010), 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu B., Xu P., Shi Q., Ma C., Deep Desulfurization of Diesel Oil and Crude Oils by a Newly Isolated Rhodococcus erythropolis Strain, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 (2006) 54–58. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.54-58.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohnishi A., Abe S., Nashirozawa S., Shimada S., Fujimoto N, Suzuki M., Development of a 16S rRNA Gene Primer and PCR-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism Method for Rapid Detection of Members of the Genus Megasphaera and Species-Level Identification, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77 (2011) 5533–5535. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00359-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gün G., Yürüm Y., Doğanay G.D., Revisiting the biodesulfurization capability of hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 revealed DBT consumption by the organism in an oil/water two-phase liquid system at high temperatures. Turkish J. Chem. 39 (2015) 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akhtar N., Ghauri M.A., Anwar M.A., Akhtar K., Analysis of the dibenzothiophene metabolic pathway in a newly isolated Rhodococcus spp., FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 301 (2009) 95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papizadeh M., Roayaei M.A., Motamedi H., Growth-phase dependent biodesulfurization of Dibenzothiophene by Enterobacter sp. strain NISOC-03. Pollution, 3 (2017) 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davoodi-Dehaghani F., Vosoughi M., Ziaee A.A., Biodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene by a newly isolated Rhodococcus erythropolis strain, Bioresour. Technol. 101 (2010) 1102–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.08.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai Y., Shao R., Qi G., Ding B.B., Enhanced Dibenzothiophene Biodesulfurization by Immobilized Cells of Brevibacterium lutescens in n-Octane–Water Biphasic System, Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 174 (2014) 2236–2244. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1184-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y., Li J., Wang C., Wang P., Growth kinetics and phenol biodegradation of psychrotrophic Pseudomonas putida LY1, Bioresour. Technol. 17 (2010) 6740–6744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohebali G., Ballb A.S., Rasekha B., Kaytasha A., Biodesulfurization potential of a newly isolated bacterium Gordonia alkanivorans RIPI90A, Enzyme Microb. Technol. 40 (2008) 578–584. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alves L., Paixão S.M., Toxicity evaluation of 2-hydroxybiphenyl and other compounds involved in studies of fossil fuels biodesulphurisation, Bioresour. Technol. 102 (2011) 9162–9166. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.06.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caro A., Boltes K., Letón P., García-Calvo E., Dibenzothiophene biodesulfurization in resting cell conditions by aerobic bacteria, J. Biochem. Eng. 35 (2007) 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maass D., de Oliveira D., de Souza A.A.U., Souza S.M.A.G.U., Biodesulfurization of a System Containing Synthetic Fuel Using Rhodococcus erythropolis ATCC 4277, Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 174 (2014) 2079–2085. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1189-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labana S., Pandey G., Jain R.K., Desulphurization of dibenzothiophene and diesel oils by bacteria, Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 40 (2005) 159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01648.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seo J.S., Keum Y.S., Cho L.L.K., Li Q.X., Degradation of dibenzothiophene and carbazole by Arthrobacter sp. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 58 (2006) 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kilbane J.J. II, Microbial biocatalyst developments to upgrade fossil fuels, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17 (2006) 305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bahuguna A., Lily M.K., Munjal A., Singh, Dangwal K., Desulfurization of dibenzothiophene (DBT) by a novel strain Lysinibacillus sphaericus DMT-7 isolated from diesel contaminated soil, J. Env. Sci. 23 (2011) 975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo M., Xing J., Gou Z., Li S., Liu H., Chen J. Desulfurization of dibenzothiophene by lyophilized cells of Pseudomonas delafieldii R-8 in the presence of dodecane. Biochem. Eng. J. 13 (2003) 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alcon A., Martin A., Santos V., Gomez E., Garcia-Ochoa F. Kinetic model for DBT desulfurization by resting whole cells of Pseudomonas putida CECT5279. Biochem. Eng. J. 39 (2008) 486–495. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez I., Santos V.E., Garcia-Ochoa F. Metabolic kinetic model for dibenzothiophene desulfurization through 4S-pathway using intracellular compound concentrations. Biochem. Eng. J. 117 (2017) 89–96. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Out of ten organisms Rhodococcus rhodochrous (3552), Artrobacter sulfureus (3332), Gordonia rubropertincta (289) and Rhodococcus erythropolis (3951) were explored for the biodesulfurization study. All these strains were thoroughly characterized with following biochemical features and maintained in the MTCC, Chandigarh.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.