Abstract

Additional sex combs-like 1 (ASXL1) is a well-known tumor suppressor gene and epigenetic modifier. ASXL1 mutations are frequent in myeloid malignances; these mutations are risk factors for the development of myelodysplasia and also appear as small clones during normal aging. ASXL1 appears to act as an epigenetic regulator of cell survival and myeloid differentiation; however, the molecular mechanisms underlying the malignant transformation of cells with ASXL1 mutations are not well defined. Using Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease (Cas9) genome editing, heterozygous and homozygous ASXL1 mutations were introduced into human U937 leukemic cells. Comparable cell growth and cell cycle progression were observed between wild-type (WT) and ASXL1-mutated U937 cells. Drug-induced cytotoxicity, as measured by growth inhibition and apoptosis in the presence of the cell-cycle active agent 5-fluorouracil, was variable among the mutated clones but was not significantly different from WT cells. In addition, ASXL1-mutated cells exhibited defects in monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Transcriptome analysis revealed that ASXL1 mutations altered differentiation of U937 cells by disturbing genes involved in myeloid differentiation, including cytochrome B-245 β chain and C-type lectin domain family 5, member A. Dysregulation of numerous gene sets associated with cell death and survival were also observed in ASXL1-mutated cells. These data provide evidence regarding the underlying molecular mechanisms induced by mutated ASXL1 in leukemogenesis.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, ASXL1 mutations, U937 cells, myeloid differentiation, RNA sequencing

Introduction

Recurrent additional sex combs-like 1 (ASXL1) mutations are frequent in myeloid malignancies, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelofibrosis and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, and they are associated with disease progression and prognosis (1–6). In particular, ASXL1 mutations are associated with high-risk MDS and leukemic transformation in MDS (4). In AML, ASXL1 mutations are more frequent in patients with aberrant karyotypes, particularly trisomy 8 (7–9). Our previous study revealed that ASXL1 mutations were frequent in patients with aplastic anemia, a disease in which a minority of patients later develops MDS and AML; ASXL1 mutations grouped with other unfavorable mutations were associated with a poor prognosis (10). Cumulative evidence has suggested that ASXL1 acts as a tumor suppressor, which leads to leukemic transformation when mutated.

The ASXL1 gene is a polycomb family member, which serves roles in activation and repression of homeobox genes by regulating the polycomb and trithorax groups of proteins (11–13). The most prominent isoform of ASXL1 (isoform 1) encodes a protein containing 1,541 amino acids, which comprises several domains, such as the putative N-terminal DNA-binding domain, the ASX homology domains and the C-terminal typical plant homeodomain (PHD) (14). ASXL1 associates with the deubiquitinating enzyme BRCA1-associated protein 1 to promote gene expression through the removal of H2A lysine 119 ubiquitination induced by polycomb repressive complex (PRC)1 (15). In addition, ASXL1 may interact with members of PRC2 to inhibit gene expression by promoting trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27). ASXL1 deletion impairs PRC2-mediated gene expression and causes severe inhibition of H3K27 trimethylation in myeloid hematopoietic cells, thus leading to malignant transformation (16). In addition, ASXL1 knockdown triggers apoptosis of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, which leads to a reduction in stem cell frequency and decreased cell expansion along the myeloid lineage (17). Loss of ASXL1 function in mice causes embryonic lethality and introduces an MDS-like phenotype after a long latency (18–20). In addition, missense and frameshift mutations of ASXL1 in cell lines and patient specimens promote myeloid transformation (2,7); these findings are consistent with the tumor suppressor role of ASXL1 (21,22).

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease (Cas9) system is a powerful genome editing technique. It utilizes a single guide RNA (gRNA) molecule to specifically alter DNA sequences, allowing study of gene functions by generating targeted knockin and knockout mutations of any gene. While some clinical and biological consequences of ASXL1 mutations have been characterized, precise molecular mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Our previous study conducted CRISPR/Cas9-engineered gene editing of a cell line, which disclosed novel and important biological consequences of DNA methyltransferase 3α mutations in K562 cells (23). Therefore, in the present study, ASXL1-mutated human hematopoietic cell lines were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing as a model system for functional studies. The ASXL1-mutated U937 cells used in the present study should be useful to obtain insights into myelomonocytic mechanisms of ASXL1 action, and to identify therapeutic strategies for hematopoietic malignancies associated with ASXL1 mutations.

Materials and methods

Generation of ASXL1-mutated U937 cell lines

The human U937 leukemic cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). U937 and its derivative cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), 1% L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C. Using the Amaxa® Cell Line Nucleofector® kit C (Lonza, Inc., Allendale, NJ, USA), 1×106 U937 cells were transfected with a pU6-gRNA plasmid (1 µg; target ID: HS0000388833, target site: GCCACGCCGATGGCGAGAGCGG; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and a pCMV-CG-Cas9-green fluorescence protein (GFP) plasmid (1 µg; product number: CAS9GFPP-1EA; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), according to the manufacturer's protocols. GFP-positive cells were separated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting 24 h post-transfection and were seeded as single cells in 96-well plates. After ~2 weeks, surviving single cell clones were selected and expanded. Aliquots of these single cell clones were stored in liquid nitrogen using freezing medium and the remaining cells were subjected to genomic DNA extraction, in order to validate gene mutations by sequencing.

Validation of ASXL1 mutations

Single cell clones were disrupted in lysis buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100 and 100 µg/ml Proteinase K] and were incubated at 56°C for 1 h in order to liberate total genomic DNA. Subsequently, cell lysates were treated at 96°C for 5 min to inactivate proteinase K and subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using the Takara LA TaqDNA Polymerase with GC Buffer (Takara Bio USA, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) as follows: 94°C for 3 min; 45 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 50 sec and 72°C for 1 min; and 72°C for 5 min. Following purification with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA), amplicons were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator version 3.1 in the ABI Prism 3100 analyzer (both from Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in both directions to confirm ASXL1 gene mutations in exon 8 (containing a targeted site of the gRNA). The following primers were used for PCR and sequencing: Forward 1, 5′-gccagaccatgaagtggtggtttc-3′; forward 2, 5′-cagaccatgaagtggtggtttctc-3′; reverse 1, 5′- ctggtaaaggaattggaatagaag-3′ a nd reverse 2, 5′-gacatcatcttctcactaggcctg-3′. All procedures were performed according to the manufacturers' protocols. According to sequencing results, transfected single cell clones were categorized into transfected wild-type (WT) clones (including WT1 and WT2 used in further experiments), and ASXL1-mutated (MT) clones (including MT+/− and MT−/−).

Cell growth and cell cycle analyses

To generate growth curves, cells in the logarithmic phase were seeded into 96-well plates at 2.5×104 cells/well (200 µl) in triplicate, and viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion over 8 consecutive days. All experiments were conducted alongside passage-matched parental U937 cells. For cell cycle analysis, 1×106 cells suspended in 1 ml NuCycl propidium iodide (PI) (Exalpha Biologicals, Inc., Shirley, MA, USA) were incubated in the dark for 20 min at 37°C, after which they were placed on ice and cell cycle progression was determined within 30 min by flow cytometry.

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU)-induced cell growth inhibition and apoptosis

To examine 5-FU-induced cell growth inhibition, cells were plated at 2×104 cells/well (200 µl) in a 96-well plate in triplicate and were treated with various concentrations of 5-FU (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 µM). A total of 48 h post-treatment, cell proliferation was evaluated using the Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) according to manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 10 µl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Subsequently, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using the PerkinElmer Victor3 V Plate Counter (Conquer Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA). The inhibitory rate was calculated as follows: [1 - (absorbance of treated cells/absorbance of control cells)] x 100%. To analyze 5-FU-induced apoptosis, cells were seeded at 2×105 cells/well (1 ml) in 24-well plates and were treated with various concentrations of 5-FU (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 µM). After 48 h, cells were harvested, washed in cold PBS, and stained with 5 µl of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) Annexin V and 10 µl of propidium iodide (PI) solution in 100 µl of Annexin V Binding Buffer (FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection kit with PI; BioLegend, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) at room temperature in the dark for 15 min, according to the manufacturer's protocol, followed by flow cytometry.

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-induced differentiation

Cells were cultured at 1×105 cells/well (1 ml) in 6-well plates for flow cytometry, or in slide chambers (Nunc Lab-Tek II Chamber Slide; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for Wright-Giemsa staining, and were subjected to treatment with various concentrations of PMA (0, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100 and 200 ng/ml). After 96 h, adhesive cells in 6-well plates were harvested using cell scrapers, washed with cold PBS and stained with anti-cluster of differentiation (CD)11b-phycoerythrin antibody (Ab) (clone M1/70, 101208; BioLegend, Inc.) at 0.02 mg/ml on ice for 30 min, followed by flow cytometry. For Wright-Giemsa staining, adherent cells in slide chambers were washed with PBS and stained with StainRITE Wright-Giemsa Stain Solution (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA, USA) to examine their morphologies using a Zeiss Axioskope 2 Plus microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) and to assess differentiation.

Gene expression analyses by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, Inc.), and was subsequently used for RNA-seq and RT-qPCR. RNA-seq was performed by Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ, USA). Briefly, samples underwent ribosomal RNA depletion, stranded RNA library preparation, multiplexing and cluster generation, followed by Illumina HiSeq2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at 2×100 base pair for paired-end sequencing in a high output mode. Sequence reads were trimmed and then aligned to the human reference genome (hg19) using Tophat2, and the featureCounts function within the Rsubread package was applied to summarize data to gene-level read counts with USCS refseq annotation (24). Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) values were calculated with cufflinks (25).

EdgeR was used to identify differentially expressed genes between groups (26) and topGO was used for annotation (27). Differentially expressed genes, which were identified using threshold P-value <0.05, fold change >2 and false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected P-value <0.20, were further subjected to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). Heatmaps containing representative top-regulated genes were generated using R (https://www.r-project.org). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using online free software http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp from the Broad Institute (Cambridge, MA, USA). Enriched gene sets were defined according to the following criteria: P<0.05 and FDR-corrected P-value <0.05. miso (28) was used to detect RNA splicing differences, specifically differentially regulated exons or isoforms.

For RT-qPCR, total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis Super Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was subjected to qPCR using the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix and the following TaqMan probes with FAM-MGB (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.): Calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit α2δ3 (CACNA2D3; Hs01045030_m1), cytochrome B-245 β chain (CYBB; Hs00166163_m1), cathepsin G (CTSG; Hs01113415_g1), actin-like 8 (ACTL8; Hs00380546_m1), NLR family apoptosis inhibitory protein (NAIP; Hs03037952_m1), oxidation resistance 1 (OXR1; Hs00757844_m1), chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4; Hs00361541_g1), C-type lectin domain family 5, member A (CLEC5A; Hs00183780_m1), and ASXL1 (Hs00392415_m1 and Hs00899495_g1). A housekeeping gene, β-actin (ACTB), was measured using the ACTB probe (Hs99999903_m1) with VIC-MGB, as an endogenous control to normalize differences in input cDNA amounts. Triplicate samples were analyzed using the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as follows: Stage 1, 95°C for 20 sec; stage 2, 40 cycles at 95°C for 3 sec and 60°C for 30 sec; data were collected at stage 2 step 2. Relative quantification was calculated using the ΔΔCq method (29).

Protein extraction, immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

For immunoblotting of CYBB and ACTL8, cells were lysed using M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing cOmplete Mini EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KgaA). The proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE (4-12% gel). For immunoblot analysis of ASXL1, cells were lysed with the radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer system (sc-24948; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), and proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-ASXL1 mouse Ab (6E2, sc-293204; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) using Dynabeads Protein G Immunoprecipitation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), followed by separation with 8% SDS-PAGE. Protein concentrations were quantified using the Micro Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and 100 µg extracted total proteins (for CYBB and ACTL8) and immunoprecipitated ASXL1 from 3.5 mg total proteins were loaded into individual wells of gels. After protein transfer onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, immunoblotting was performed with the following primary Abs: Anti-CYBB rabbit Ab (NOX2/gp91phox, ab129068), anti-ACTL8 rabbit Ab (ab184562) (both from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-ASXL1 Ab (6E2, sc-293204; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and anti-GAPDH Rabbit Ab (#2118; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA). After incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) Ab (sc-2004; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or anti-mouse IgG Ab (m-IgGκ BP-HRP; sc-516102), signals were detected using the SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate and/or the SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and blots were visualized using the ImageQuant LAS 4000 system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). GAPDH was used as a loading control, and GAPDH expression of remaining cell lysates was measured as a loading control for immunoprecipitated ASXL1 protein fractions.

Flow cytometry and statistical analyses

Intracellular staining of CYBB was performed according to Novus Biologicals General Intracellular Cytoplasmic Target Flow Protocol (https://www.novusbio.com/support/support-by-application/general-intracellular-cytoplasmic-target-flow-protocol). Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde prior to permeabilization with 1X PBS + 0.5% Tween-20. Anti-CYBB/NOX2-PE Ab (NL7, NBP1-41012PE; Novus Biologicals, LLC, Littleton, CO, USA) and anti-MDL-1/CLEC5A-Alexa Fluor 488 Ab (FAB2384G; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were used to detect CYBB and CLEC5A expression. For all flow cytometry experiments, data acquisition was performed using BD Fortessa (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and data were subjected to analysis using FlowJo software version 7.6.4 (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). Experiments were conducted in triplicate unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as the means ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance for comparisons between three or more groups (GraphPad Prism, version 7.02; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Generation of ASXL1-mutated U937 cell lines using CRISPR/Cas9

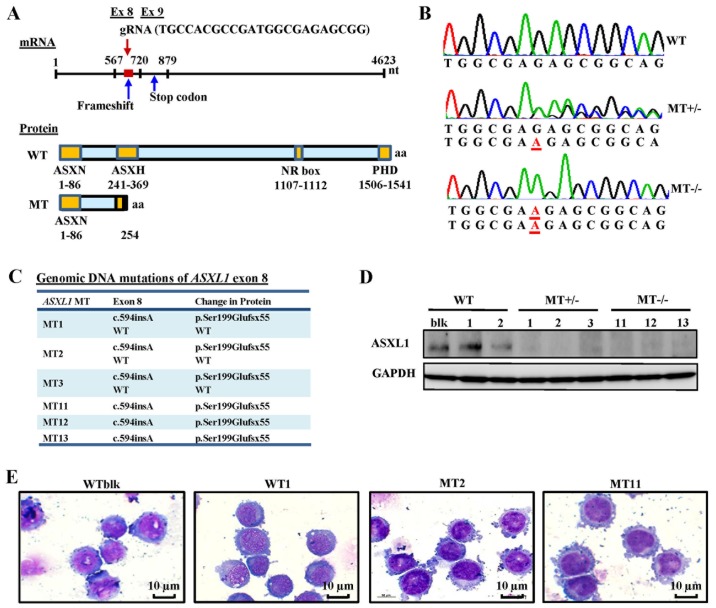

ASXL1 mutations were introduced into U937 cells using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. The ASXL1 gene was initially sequenced in wild-type bulk parental (WTblk) U937 cells and confirmed the absence of pathogenic mutations, with the exception of a heterozygous substitution (c.604C>A, p.Pro602Thr) reported as a polymorphism by comparison with its published nucleotide sequence (isoform 1, NM_015338). The gRNA used in the present study targeted a specific site (nt1010-1031) of exon 8 in ASXL1, which contains 13 exons in total. Using Sanger sequencing, the present study observed a c.594insA (Ser199Glufsx55) mutation, which creates a short, truncated protein followed by 55 additional amino acids, due to a premature termination codon (Fig. 1A–C), thus resulting in a protein consisting of only the N-terminal ASXN domain. A total of 6 MT cell lines, including MT+/− (MT1, MT2 and MT3) and MT−/− (MT11, MT12 and MT13), and transfected WT cell lines (WT1 and WT2 derived from transfecting single cell clones with WT ASXL1) were used for further experiments. Introduced ASXL1 mutations were observed in mRNA sequences of individual cell lines using RNA-seq data (data not shown). ASXL1 protein expression was also decreased in MT+/− cell lines and was not detectable in MT−/− cell lines (Fig. 1D). The cell morphology of ASXL1-mutated U937 cell lines appeared indistinguishable from that of WT cells, as determined by conventional microscopy (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Generation of ASXL1-mutated U937 cell lines using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. (A) Schematic diagrams of ASXL1 mRNA, and ASXL1-WT and ASXL1-MT proteins. The target site of gRNA, frameshift mutation and truncated proteins are indicated. (B) Representative electropherograms, as determined by Sanger sequencing, for the evaluation of ASXL1 mutations in exon 8 introduced by CRISPR/Cas9. Inserted nucleotides are underlined in red. (C) ASXL1 mutations in exon 8 of all mutated cell lines with associated changes in ASXL1 protein. All genomic and protein sequence variants are represented using the Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature. WT indicates a WT sequence without mutations. (D) Immunoblot analysis of ASXL1 in WT and MT cell lines. Immunoprecipitated protein samples were subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. (E) Representative images of Wright-Giemsa-stained WTblk, WT1, MT2 and MT11 U937 cells in logarithmic growth phase. ASXL1, additional sex combs-like 1; CRISPR/Cas9, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease; Ex, exon; gRNA, guide RNA; NR, nuclear receptor; PHD, plant homeodomain; MT, mutated; WT, wild-type; WTblk, wild-type bulk parental.

ASXL1 mutations have little impact on cell proliferation and cell cycle progression of U937 cells

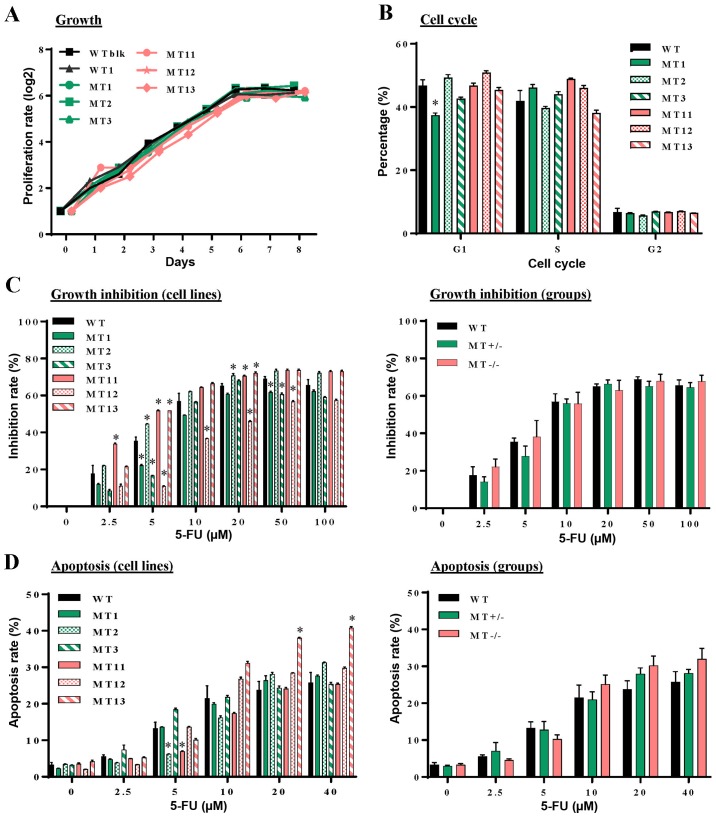

The present study hypothesized that ASXL1-mutated U937 cells may possess abnormalities in essential cellular functions, including proliferation, cell cycle progression, apoptosis and resistance to cytotoxic drugs. Growth curves were similar among the WT (WTblk and WT1), MT+/− (MT1, MT2 and MT3) and MT−/− (MT11, MT12 and MT13) cell lines (Fig. 2A). Distribution among the G1, S and G2 phases of the cell cycle exhibited modest variations among the individual cell lines (Fig. 2B). 5-FU is an inhibitor of thymidylate synthesis that interferes with DNA replication by inducing double-strand breaks. The present study examined susceptibility of ASXL1-mutated U937 cells to 5-FU. The results indicated that their growth inhibition rates were elevated with increasing 5-FU concentration, plateauing at ~20 µM, and variations were detected among the ASXL1-mutated cell lines and the WTblk and WT1 cells (Fig. 2C, left panel). However, average inhibition rates were similar among the WT, MT+/− and MT−/− groups (Fig. 2C, right panel). Similarly, apoptosis following exposure to 5-FU was not significantly different among almost all of the cell lines (Fig. 2D, left panel), or among the WT, MT+/− and MT−/− groups (Fig. 2D, right panel).

Figure 2.

Effects of CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease-mediated additional sex combs-like 1 mutations on cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and 5-FU induced growth inhibition and apoptosis. (A) Proliferation of individual WT, MT+/− and MT−/− U937 cell lines was measured at different time-points in culture by counting viable cells using a trypan blue exclusion procedure. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle progression with PI DNA staining was performed at logarithmic growth phase during the culture of WT, MT+/− and MT−/− cells. (C) Following treatment of WT, MT+/− and MT−/− cells with various concentrations of 5-FU for 48 h, cell proliferation was measured using cell counting kit-8 and inhibition rates were calculated compared with untreated samples of the corresponding cells. Left panel, inhibition rates of individual cell lines; right panel, average inhibition rates of WT, MT+/− and MT−/− U937 cell groups. (D) Following treatment with various concentrations of 5-FU, cell apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry with Annexin V and PI staining. Left panel, percentages of apoptotic cells in individual cell lines; right panel, average percentages of individual groups. WT in (B-D) indicates average values derived from WTblk, WT1 and WT2 cells. Data are presented as the means ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05 vs. the WT group, one-way analysis of variance. 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; CRISPR/Cas9, clustered regulaly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease; PI, propidium iodide; MT, mutated; WT, wild-type; WTblk, wild-type bulk parental.

ASXL1 mutations impair PMA-induced differentiation of U937 cells

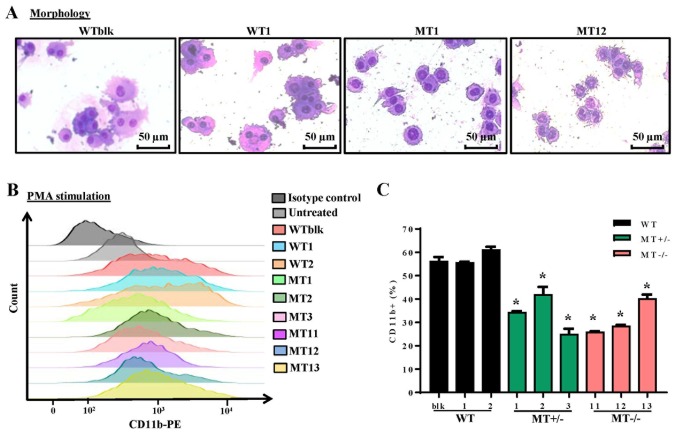

The U937 cell line is widely employed as a model of monocyte/macrophage differentiation following treatment with PMA, which is a typical inducer of differentiation. Following treatment with PMA for 96 h, WT, MT+/− and MT−/− cell lines were examined by Wright-Giemsa staining to detect morphology, and by flow cytometry to detect CD11b expression; CD11b is a pan-macrophage marker that is highly expressed in monocytes and macrophages. The majority of cells differentiated into macrophages and adhered to the plates. WT cells (WTblk and WT1) were larger and richer in cytoplasm compared with MT cells (MT2 and MT11) (Fig. 3A). As determined by flow cytometry, there were fewer CD11b-positive cells in the MT+/− and MT−/− groups compared with in the WT group following PMA treatment (Fig. 3B and C). These results indicated that ASXL1-mutated U937 cells were less responsive to PMA-induced differentiation.

Figure 3.

Effects of ASXL1 mutations on the differentiation of PMA-treated U937 cells. Following treatment with various concentrations of PMA, cells were harvested at 96 h. (A) Representative images of Wright-Giemsa-stained WT and ASXL1-mutated U937 cell lines, which attached to chamber slides following 200 ng/ml PMA-induced differentiation. (B) CD11b expression in cells harvested from slide chambers, as determined by flow cytometric analysis. (C) Percentages of CD11b-positive cells in WT and MT U937 cells calculated using flow cytometry data. Data are presented as the means ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05 vs. the WT group (WTblk, WT1 and WT2), one-way analysis of variance. ASXL1, additional sex combs-like 1; CD11b, cluster of differentiation 11b; PE, phycoerythrin; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; MT, mutated; WT, wild-type; WTblk, wild-type bulk parental.

RNA-seq reveals dysregulated gene expression profiles in ASXL1-mutated U937 cell lines

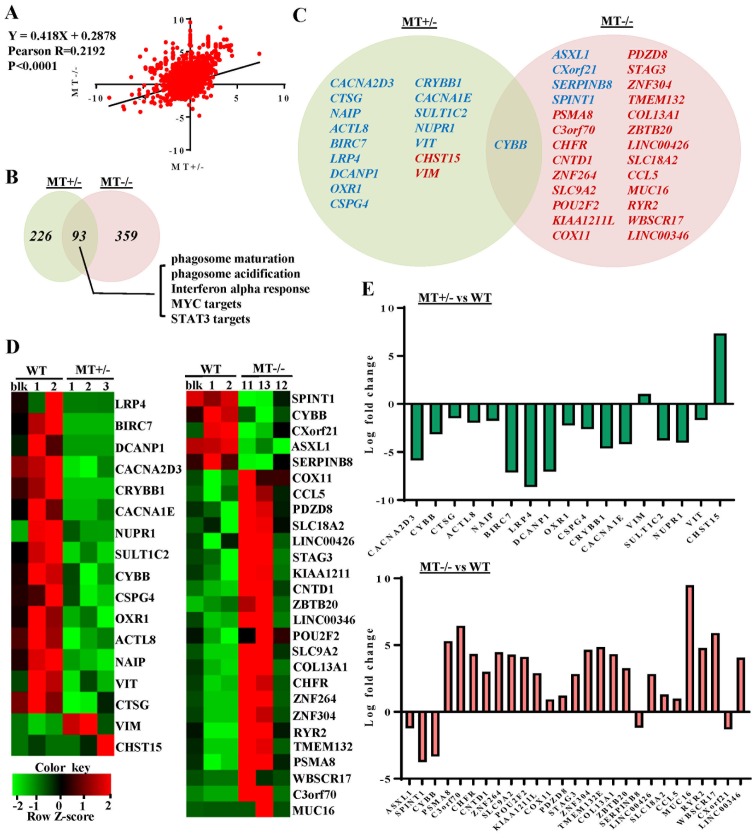

To characterize the molecular mechanisms underlying differentiation defects, and to obtain dysregulation profiles of ASXL1-mutated U937 cells, RNA-seq of WT and ASXL1-mutated U937 cell lines was performed. When compared with the WT group (WTblk, WT1 and WT2), with criteria of >2-fold change and P<0.05, 107 upregulated and 54 downregulated genes were identified in the MT group (including MT1-MT3 and MT11-MT13; data not shown). At an FDR-corrected P<0.05, CYBB was the only differentially expressed gene in the MT group compared with the WT group. Considering likely variations in gene expression within the MT group, the present study analyzed the differentially expressed genes in the MT+/− (MT1-MT3) and MT−/− (MT11-MT13) groups relative to the WT group, with cutoff values of P<0.05, fold change >2 and FDR-corrected P<0.20 (Fig. 4). By determining the fold changes of individual genes in the MT+/− and MT−/− groups relative to the WT group, a linear correlation (P<0.0001 and Pearson R-value, 0.2192) was observed between the MT+/− and MT−/− groups (Fig. 4A). When compared with the WT group, 15 downregulated and 2 upregulated genes were detected in the MT+/− group, whereas 5 downregulated and 22 upregulated genes were identified in the MT−/− group. In addition, only CYBB was differentially expressed (downregulated) in both groups relative to WT (Fig. 4C and D). Log fold changes of the differentially expressed genes ranged between -10 and 10 (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Gene expression analysis of WT and ASXL1-mutated U937 cells by RNA-seq. (A) Linear correlation of fold changes of all genes between MT+/− (MT1-MT3) and MT−/− (MT11-MT13) groups. Pearson R-value, 0.2192; P<0.0001. (B) Venn diagrams indicate the number of differentiated gene sets in the MT+/− and MT−/− groups, compared with the WT group, as determined by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Representative commonly skewed gene sets in MT+/− and MT−/− were listed. (C) Venn diagrams demonstrating the significantly upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes (P<0.05; fold change >2; false discovery rate-corrected P<0.20) in the MT+/− or MT−/− groups compared with the WT (WTblk, WT1 and WT2) group. Expression levels and fold changes of significantly upregulated and downregulated genes are shown by (D) heat maps and (E) bar graphs. ASXL1, additional sex combs-like 1; MT, mutated; WT, wild-type; WTblk, wild-type bulk parental.

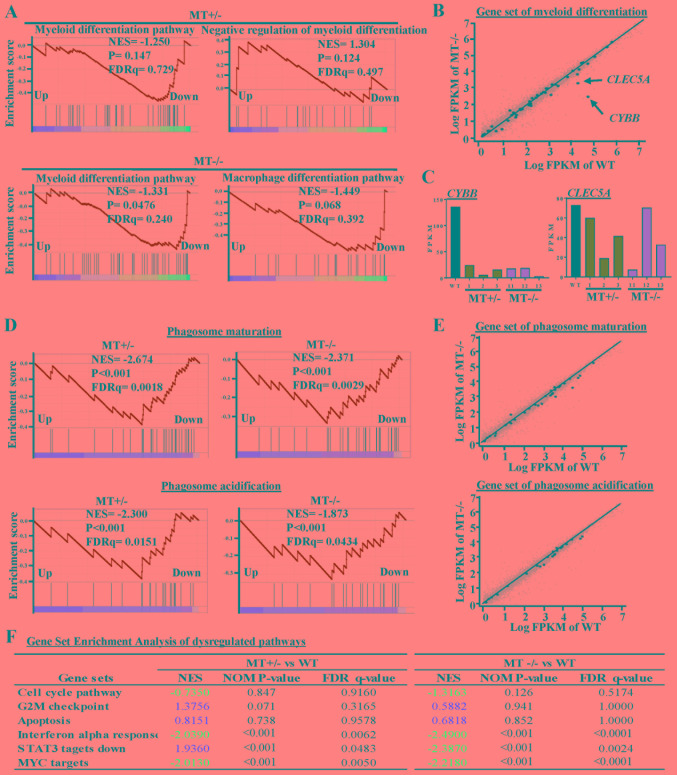

ASXL1 mutations dysregulate transcriptional programs associated with U937 cell differentiation and survival

To further explore the effects of ASXL1 mutations on the molecular machinery of U937 cells, GSEA was performed in MT+/− (MT1-MT3) and MT−/− (MT11-MT13) groups, and the results were compared to the WT (WTblk, WT1 and WT2) group (Fig. 5). There were 93 common skewed gene sets shared by MT+/− and MT−/−, whereas in total, MT−/− cells harbored 133 more skewed gene sets than MT+/− cells (Fig. 4B). A gene set associated with the negative regulation of myeloid differentiation was upregulated in the MT+/− group while the macrophage differentiation pathway was specifically downregulated in the MT−/− group (Fig. 5A and B). Apoptosis gene sets exhibited no significant alterations in the MT+/− and MT−/− groups compared with in the WT group; this finding is consistent with the results of the functional assay (Fig. 5F). Two genes (CYBB and CLEC5A) that were revealed to be highly associated with myeloid cell differentiation were downregulated in the MT groups, as determined by gene set analysis of RNAseq data (Fig. 5B and C). Gene sets associated with monocyte functions, including phagosome maturation and phagosome acidification, were also downregulated in the MT groups (Fig. 5D and E). Other gene sets associated with various cell functions were downregulated in the MT+/− and MT−/− cells: Monocyte functions (such as ATP synthesis, oxidative phosphorylation and respiratory chain), cell development and survival, cell growth and death (such as interferon α response, MYC targets, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 targets), and cell-to-cell signaling and interaction (Fig. 4B).

Figure 5.

GSEA of dysregulated pathways in MT+/− and MT−/− U937 cell lines. (A) GSEA plots represent decreased expression of gene sets involved in myeloid differentiation-related pathways in MT+/− (MT1-MT3) and MT−/− (MT11-MT13) groups relative to the WT (WT bulk parental, WT1 and WT2) group. NES, P-value and FDRq value (FDR-corrected P-value) are presented. (B) Scatter plot of genes in the myeloid differentiation pathway, as constructed by comparing Log FPKM values between the MT−/− and the WT groups. Black or small grey dots represent genes in the myeloid differentiation pathway and all genes detected by RNA sequencing, respectively; CYBB and CLEC5A are indicated with arrows. (C) FPKM values of CYBB and CLEC5A in RNA-seq data. (D) GSEA of phagosome maturation and phagosome acidification gene sets for the MT+/− and MT−/− groups compared with the WT group. (E) Scatter plots of phagosome maturation (top panel) and phagosome acidification (bottom panel) gene sets for the MT−/− group in which x- and y-axes refer to the Log FPKM of MT−/− and Log FPKM of WT groups, respectively. (F) Six representative pathways associated with the cell cycle, apoptosis and other signaling pathways. NES are highlighted in blue (downregulated) and red (upregulated). CLEC5A, C-type lectin domain family 5, member A; CYBB, cytochrome B-245 β chain; FDR, false discovery rate; FPKM, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads; GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; MT, mutated; NES, normalized enrichment score; WT, wild-type.

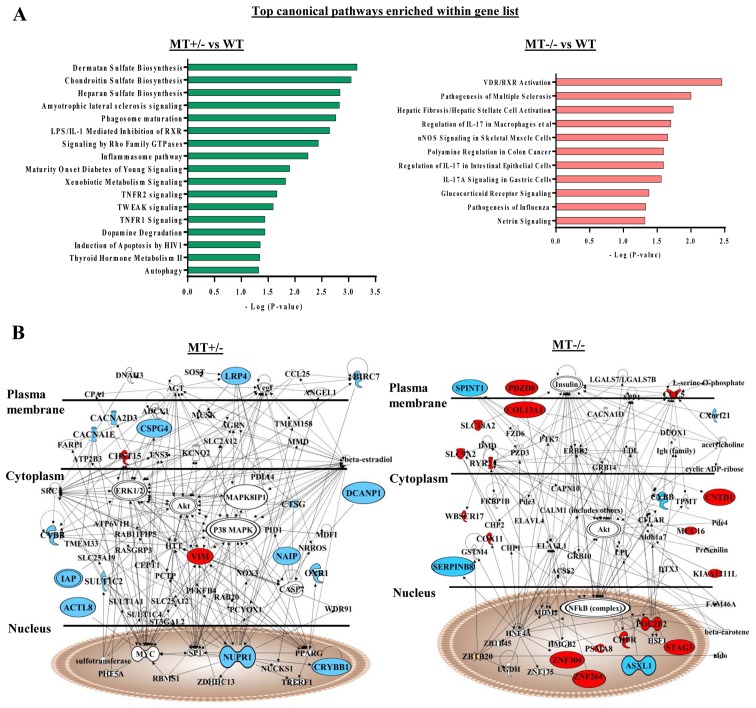

IPA of differentially expressed genes was performed in the MT+/− and MT−/− groups compared with in the WT group. Some of these genes were revealed to be involved in the phagocyte development signaling pathway, which is consistent with the GSEA data of defects in monocyte/macrophage differentiation of ASXL1-mutated cells (Fig. 6A). In addition, protein products from differentially expressed genes in the MT+/− group were interconnected, and were involved in cell death and survival signaling [such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (TNFR)1, TNFR2 and TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis]; these proteins were components of a comprehensive network, with mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), protein kinase B (AKT), extracellular signal-regulated kinase, nuclear factor (NF)-κB, caspase and MYC as molecular hubs (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

IPA of RNA-seq data from WT and ASXL1-mutated U937 cells. (A) Differentially expressed genes in the MT+/− (MT1-MT3) and MT−/− (MT11-MT13) groups compared with in the WT (WTblk, WT1 and WT2) group (P<0.05; fold change >2; and false discovery rate-corrected P<0.20) were subjected to IPA. -Log (P-value) and aberrant pathways are indicated at x- and y-axes, respectively. (B) Subcellular networks of differentially expressed genes and involved pathways in the MT+/− or MT−/− U937 groups relative to the WT group. Upregulated and downregulated genes are shown in red and blue, respectively. ASXL1, additional sex combs-like 1; IPA, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis; MT, mutated; WT, wild-type.

To validate altered gene expression detected by RNA-seq analysis, RT-qPCR, immunoblotting and flow cytometry were performed. RT-qPCR confirmed that the expression levels of genes essential for myeloid differentiation were significantly reduced, including CYBB and CLEC5A, and that genes involved in cell death and survival, such as NAIP, CACNA2D3, ACTL8, CTSG, OXR1 and CSPG4, were decreased in ASXL1-mutated cells compared with in WT cells (Fig. 7A). ASXL1 expression was also assessed by RT-qPCR using two different primer sets (set 1, nt799-865; set 2, nt1151-1248); the results indicated that ASXL1 expression was reduced in MT+/− and MT−/− cells compared with in WT cells (Fig. 7B), which are in agreement with the RNA-seq results. For comparison, the FPKM values of ASXL1 from RNA-seq of the WT and MT cell lines are also shown in Fig. 7B. Reduced ASXL1 expression in ASXL1-mutated cells may be attributed to premature stop codons created by single nucleotide insertion, since degradation of transcripts containing premature stop codons is the evolutionarily conserved mRNA quality control system in all eukaryotes (30). Consistent with gene expression levels, CYBB (Fig. 7C and D) and CLEC5A (Fig. 7D) protein expression levels were reduced in MT+/− and MT−/− cells compared with in WT cells. These results indicated that ASXL1 mutations markedly affected the molecular machinery of U937 cells by dysregulating the expression of genes essential for myeloid differentiation; notable effects were detected on gene sets associated with cell death and survival.

Figure 7.

Validation of RNA-seq data by RT-qPCR and immunoblotting. (A) Expression levels of genes in WT and ASXL1-mutated U937 cells were validated using RT-qPCR. Data are presented as the means ± standard error of the mean (*P<0.05 vs. the WT group, one-way analysis of variance). (B) ASXL1 expression was also validated by RT-qPCR using two primer sets targeted before (ASXL1-probe 1) and after (ASXL1-probe 2) the mutation point. FPKM values from RNA-seq data obtained from individual WT and ASXL1-mutated cell lines are also shown (ASXL1-FPKM). (C) Proteins extracted from WT, MT+/− and MT−/− cells were subjected to immunoblotting to measure CYBB and ACTL8 protein expression levels using GAPDH as a loading control. (D) Histograms of CYBB expression and MFI of CYBB (left panel), and histograms of CLEC5A expression and MFI of CLEC5A (right panel) in WT and MT U937 cells. Data are presented as the means ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05 vs. the WT group (WTblk, WT1 and WT2), one-way analysis of variance. ACTL8, actin-like 8; ASXL1, additional sex combs-like 1; CACNA2D3, calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit α2δ3; CLEC5A, C-type lectin domain family 5, member A; CTSG, cathepsin G; CYBB, cytochrome B-245 β chain; FPKM, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; NAIP, NLR family apoptosis inhibitory protein; OXR1, oxidation resistance 1; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; MT, mutated; WT, wild-type; WTblk, wild-type bulk parental.

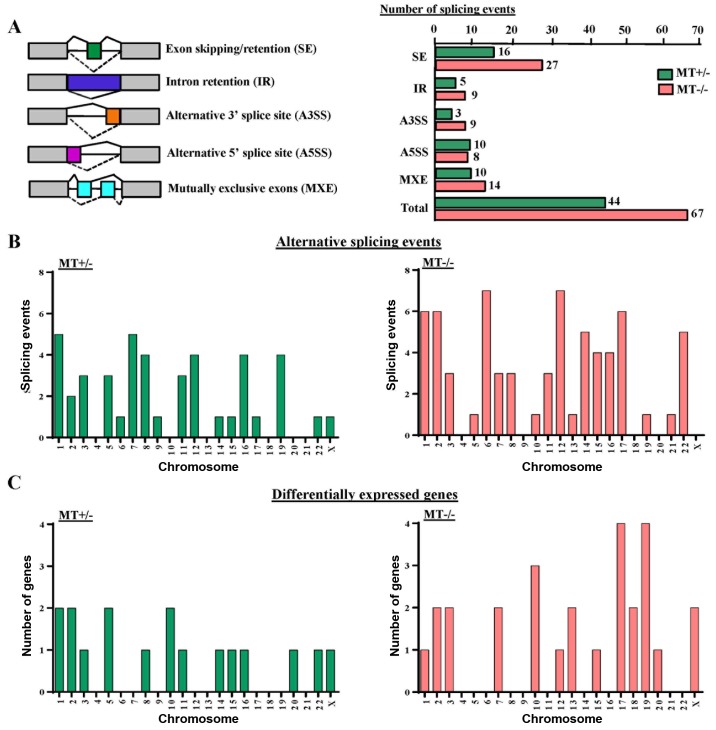

ASXL1 mutations cause altered gene splicing in U937 cells

GSEA analysis revealed that gene sets associated with mRNA splicing were downregulated in the MT cell lines (data not shown). Therefore, the present study analyzed alternative splicing in ASXL1-mutated U937 cells. In total, 44 and 67 differential splicing events were observed in the MT+/− and MT−/− cell lines compared with the WT group, respectively. These events could be categorized into five different patterns of alternative splicing, among which 16 (36.4%) and 27 (40.3%) genes represented abnormal exon inclusion and/or retention in MT+/− and MT−/− cells, respectively (Fig. 8A). Calculation of differential splicing events on each chromosome revealed that ASXL1 mutations affected alternative splicing on individual chromosomes randomly, with no preference for any specific chromosomes (Fig. 8B). In addition, the affected chromosomes containing differentially expressed genes were analyzed in MT+/− and MT−/− cells; however, there was no preference for chromosomes containing differentially expressed genes (Fig. 8C). Notably, differentially spliced genes in the MT cell lines were highly associated with gene expression regulation, cell cycle, apoptosis, DNA/RNA/protein synthesis and even RNA splicing itself, including the spliceosomal gene LUC7-like, small nuclear ribonucleoprotein D3 polypeptide (a core component of the spliceosome) and pre-mRNA processing factor 40 homolog A (data not shown). Alternative splicing of solute carrier family 25 member 37 (SLC25A37), synoviolin 1 (SYVN1), enhancer of zeste 1 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH1), zinc finger protein 227 (ZNF227) and ADP-dependent glucokinase (ADPGK) were detected in ASXL1-mutated cell lines (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Analysis of alternative splicing events. (A) Left panel, different types of alternative splicing observed, including SE, IR, alternative splice sites A5SS and A3SS, and MXE. For individual pre-mRNAs, solid and dotted lines represent different types of alternative splicing patterns. Right panel, number of each type of alternative splicing event in the ASXL1 MT+/− and MT−/− U937 groups. (B) Bar charts indicate the number of alternative splicing events on individual chromosomes in the MT+/− and MT−/− group. (C) Bar charts present the number of differentially expressed genes on individual chromosomes in the MT+/− and MT−/− groups. MT, mutated.

Discussion

To determine the molecular and cellular consequences of ASXL1 mutations, the present study generated ASXL1-MT+/− and ASXL1-MT−/− U937 cell lines. These mutated cells produced short, truncated ASXL1 proteins lacking most of the C-terminus domain, thus mimicking the majority of ASXL1 mutations in myeloid malignancies, in which reported point or frameshift mutations result in alterations, or partial or complete loss, of the C-terminus PHD domain. ASXL1-mutated U937 cells displayed comparable cell growth and cell cycle progression as WT cells; however, defects were observed in PMA-induced monocyte/macrophage differentiation. RNA-seq revealed that ASXL1 mutations led to dysregulation of genes involved in myeloid differentiation, including downregulation of CYBB and CLEC5A. Gene sets associated with various cellular functions, such as cell growth and cell death were also impaired in ASXL1-mutated cells. Furthermore, gene splicing analysis implicated ASXL1 mutations in altered mRNA splicing.

Previous studies have investigated the effects of ASXL1 knockdown on cell survival, with variable results. ASXL1 knockdown did not affect proliferation or apoptosis of human CD34+ cells (31), whereas ASXL1-mutated KBM5 cells derived from chronic myelogenous leukemia cells exhibited a growth advantage following ASXL1-mutation correction (32). Enforced expression of ASXL1 in murine leukemic cells resulted in growth suppression (16); similarly, hematopoietic-specific ASXL1 knockdown manifested as impaired hematopoiesis, increased apoptosis and altered cell cycle regulation of mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (17). In the present study, significant abnormalities in cell growth, cell cycle progression and apoptosis were not observed in ASXL1-mutated cells compared with in the WT cells, with the exception of some variation among individual clones, which may be associated with clonal expansion and stochastic selection of cells with enhanced proliferative capacity in vitro.

In response to various stimuli, U937 cells become adherent to substrates, exhibit slow proliferation and display cell surface antigen characteristics of monocytes/mature macrophages (33,34). U937 cells are used to investigate the mechanisms underlying monocyte/macrophage differentiation and monocyte-endothelium attachment. In the present study, upon stimulation with PMA, ASXL1-mutated U937 cells displayed less CD11b-positive cells and low CD11b intensity compared with in the WT cells, thus indicating a decreased response to PMA and thereby inefficient PMA-induced monocyte/macrophage differentiation. According to the two-hit model of AML development (35), these results are supportive of ASXL1 as a class II gene, in which mutations impair cell differentiation.

Due to the variability of RNA-seq data among single-cell derived cell lines, less stringent statistical criteria (FDR-corrected P<0.20, instead of 0.05) were applied for analysis of RNA-seq data, in order to screen differentially expressed genes. RT-qPCR data also displayed variability of gene expression among the cell lines, indicating biological heterogeneity among individual cell lines rather than technical irreproducibility. Among the differentially expressed genes, CYBB and CLEC5A, which are involved in myeloid differentiation, were downregulated in the MT+/− and MT−/− groups, and CYBB was the most consistently downregulated gene in the present study. CYBB encodes the gp91-phox component of the phagocyte oxidase enzyme complex, and its expression is restricted to terminally differentiating myeloid cells beyond the promyelocyte stage (36). CYBB downregulation decreases production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are involved in cell signaling associated with differentiation, cell cycle and apoptosis. ROS prime Drosophila hematopoietic progenitors for differentiation (37), and ROS levels are low in mammalian hematopoietic stem cells but high in common myeloid progenitors (38). CLEC5A is a cell surface receptor strongly associated with myeloid maturation (39). In the mouse 32Dcl3 cell line, ASXL1 mutations suppressed methylation of histone H3K27 located near the transcription start site of microRNA (miR)-125a, which led to suppression of miR-125, which in turn repressed Clec5a expression, directly inhibiting cellular differentiation (17). CLEC5A mRNA expression is also known to be low in primary MDS and AML patient samples compared with in samples from healthy donors (17,40). The downregulation of CYBB and CLEC5A may be related, in part, to the diminished response of ASXL1-mutated U937 cells to PMA.

Differentially expressed genes in ASXL1-mutated U937 cells were interconnected and scattered within a comprehensive network, the key molecular hubs of which included classical pathways of cell functions, such as MAPK, AKT, NF-κB and MYC. Among the differentially expressed genes validated by RT-qPCR, NAIP, CACNA2D3 and CSPG4 were consistently downregulated in individual MT+/− and MT−/− cell lines. These genes are involved in cell apoptosis and/or tumorigenicity (41-45). In addition, the three MT+/− cell lines displayed downregulated ACTL8, CTSG and OXR1 expression compared with in the WT cells, whereas some of the MT−/− cell lines exhibited different expression (downregulated or not significantly different). These three genes are involved in various aspects of cellular mechanisms, including hematopoietic cell survival (46,47). There were more aberrant gene sets identified in the MT−/− cell lines than in the MT+/− cells, thus suggesting that complete loss of ASXL1 appeared to have more complex transcriptional consequences than were observed in the MT+/− cell lines with a partial loss. No dose-effects were observed with regards to cell functions, perhaps due to lethality (a much lower yield of MT−/− single cell clones was observed than of MT+/− following CRISPR/Cas9 editing); therefore, milder defects may have been detected in MT−/− clones as a result of clone selection. Alternatively, gain-of-function or dominant-negative roles of truncated ASXL1 have been suggested by other studies (48-51).

More than 50% of patients with MDS harbor mutations in genes encoding proteins involved in pre-mRNA splicing (52). ASXL1 mutations appear to cooperate with mutations in genes encoding splicing factors [including splicing factor 3b subunit 1 (SF3B1), U2 small nuclear RNA auxiliary factor 1 (U2AF1), and serine and arginine rich splicing factor 2] in MDS. For example, ASXL1 mutations are more frequent in patients with U2AF35-mutated MDS compared with in patients with U2AF35 WT MDS (53,54). The present study observed alternative splicing events in ASXL1-mutated U937 cell lines, which affected genes related to cell survival and the regulation of gene expression. However, there is no direct evidence to suggest that alternative splicing is the mechanism responsible for altered gene expression. Several alternatively spliced genes (SLC25A37, SYVN1, EZH1, ZNF227 and ADPGK) detected in the ASXL1-mutated cell lines in the present study were also shown to exhibit differential usage of exons in patients with MDS with SF3B1 mutations (55,56). Ankyrin repeat and MYND domain containing 1 and chromosome 17 open reading frame 62, which were found to be differentially spliced in the present study (data not shown), were reported to be associated with U2AF1 mutations in leukemic cell lines (57). Further investigation is required to better define the effects of mutated ASXL1 on splicing patterns, and to elucidate the relationship between ASXL1 and commonly mutated spliceosome genes in clinical samples.

Using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, ASXL1 mutations were introduced into U937 cells by electroporation of a plasmid and gRNA, instead of viral infection, in order to avoid continued gene expression from the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery. The present study has the following limitations: The use of a cell line and the application of less strict criteria (FDR <0.20) to screen differentially expressed genes for discovery purposes. A more applicable model for myeloid malignancies is the use of primary cells; however, gene editing of CD34+ cells is technically challenging, due to the low efficiency of mutation induction, very limited survival of cells in vitro, and their heterogeneity and propensity to mature in cell culture. Single cell clones in the present study manifested larger variations than anticipated from data derived from bulk cell samples. CRISPR/Cas9 introduces gene mutations with low efficiency (<10% in the present study), and various types of mutations are introduced into targeted exons of individual cells by homologous recombination following double strand breaks. Therefore, the single-cell-clone method was adopted and three clones with identical mutations were used in the MT+/− and MT−/− groups, and two transfected single cell clones with WT ASXL1, as well as U937 WTblk cells comprised the WT group. Despite variations among the clones and a less stringent threshold for expression screening, nine differentially expressed genes were validated by qPCR and/or immunoblotting. In addition, variability of these differentially expressed genes among the ASXL1-mutated cell lines may be attributed to heterogeneity of individual MT cell lines. A total of 20 loci most likely to occur as off-site targets were predicted using the online MIT CRISPR sgRNA design tool (http://crispr.mit.edu/) and were assessed by RNA sequencing; no off-target mutations were observed in any of the cell lines used in the present study (data not shown).

In conclusion, ASXL1 mutations, which are potential class II gene mutations in leukemogenesis, disrupted monocyte/macrophage differentiation in U937 cells, which is a hallmark of myeloid malignancies, by downregulating genes essential to myeloid differentiation, including CYBB and CLEC5A. In addition, ASXL1 mutations affected numerous gene sets involved in cell survival, and appeared to induce altered splicing in mutated cell lines. ASXL1-MT+/− mutations in the present study better mimicked abnormality in patients, whereas homozygous mutations likely exhibited more pronounced dysregulated biological behavior and gene expression. ASXL1-mutated U937 cell lines may therefore be considered helpful to further elucidate the molecular mechanisms of ASXL1 in hematopoiesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Valentina Giudice (Hematology Branch, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), for her advice and helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Funding

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/); accession no. GSE98104 (available May 1, 2018).

Authors' contributions

ZJW, XZ, LGB, SK and NSY participated in the design of the present study. ZJW conceptualized, conducted experiments, analyzed data, interpreted results and drafted the manuscript. FGR and DQR conducted experiments and data acquisition. KK conducted cell sorting. SGG conducted the bioinformatics analysis. XZ, DQR, and SK edited the manuscript. NSY was involved in conceptualization, interim discussions and interpretation of results, and edited the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript content and agree with the submission of the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Rocquain J, Carbuccia N, Trouplin V, Raynaud S, Murati A, Nezri M, Tadrist Z, Olschwang S, Vey N, Birnbaum D, et al. Combined mutations of ASXL1, CBL, FLT3, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2, KRAS, NPM1, NRAS, RUNX1, TET2 and WT1 genes in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemias. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:401. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelsi-Boyer V, Trouplin V, Adélaïde J, Bonansea J, Cervera N, Carbuccia N, Lagarde A, Prebet T, Nezri M, Sainty D, et al. Mutations of polycomb-associated gene ASXL1 in myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:788–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boultwood J, Perry J, Pellagatti A, Fernandez-Mercado M, Fernandez-Santamaria C, Calasanz MJ, Larrayoz MJ, Garcia-Delgado M, Giagounidis A, Malcovati L, et al. Frequent mutation of the polycomb-associated gene ASXL1 in the myelodysplastic syndromes and in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1062–1065. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thol F, Friesen I, Damm F, Yun H, Weissinger EM, Krauter J, Wagner K, Chaturvedi A, Sharma A, Wichmann M, et al. Prognostic significance of ASXL1 mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2499–2506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelsi-Boyer V, Trouplin V, Roquain J, Adélaïde J, Carbuccia N, Esterni B, Finetti P, Murati A, Arnoulet C, Zerazhi H, et al. ASXL1 mutation is associated with poor prognosis and acute transformation in chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2010;151:365–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inoue D, Kitaura J, Matsui H, Hou HA, Chou WC, Nagamachi A, Kawabata KC, Togami K, Nagase R, Horikawa S, et al. SETBP1 mutations drive leukemic transformation in ASXL1-mutated MDS. Leukemia. 2015;29:847–857. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schnittger S, Eder C, Jeromin S, Alpermann T, Fasan A, Grossmann V, Kohlmann A, Illig T, Klopp N, Wichmann HE, et al. ASXL1 exon 12 mutations are frequent in AML with intermediate risk karyotype and are independently associated with an adverse outcome. Leukemia. 2013;27:82–91. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zong X, Yao H, Wen L, Ma L, Wang Q, Yang Z, Zhang T, Chen S, Depei W. ASXL1 mutations are frequent in de novo AML with trisomy 8 and confer an unfavorable prognosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:204–206. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1179296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alpermann T, Haferlach C, Eder C, Nadarajah N, Meggendorfer M, Kern W, Haferlach T, Schnittger S. AML with gain of chromosome 8 as the sole chromosomal abnormality (+8 sole) is associated with a specific molecular mutation pattern including ASXL1 mutations in 46.8% of the patients. Leuk Res. 2015;39:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshizato T, Dumitriu B, Hosokawa K, Makishima H, Yoshida K, Townsley D, Sato-Otsubo A, Sato Y, Liu D, Suzuki H, et al. Somatic Mutations and Clonal Hematopoiesis in Aplastic Anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:35–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher CL, Lee I, Bloyer S, Bozza S, Chevalier J, Dahl A, Bodner C, Helgason CD, Hess JL, Humphries RK, et al. Additional sex combs-like 1 belongs to the enhancer of trithorax and polycomb group and genetically interacts with Cbx2 in mice. Dev Biol. 2010;337:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park UH, Yoon SK, Park T, Kim EJ, Um SJ. Additional sex comb-like (ASXL) proteins 1 and 2 play opposite roles in adipogenesis via reciprocal regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor {gamma} J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1354–1363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho YS, Kim EJ, Park UH, Sin HS, Um SJ. Additional sex comb-like 1 (ASXL1), in cooperation with SRC-1, acts as a ligand-dependent coactivator for retinoic acid receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17588–17598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katoh M. Functional and cancer genomics of ASXL family members. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:299–306. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheuermann JC, de Ayala Alonso AG, Oktaba K, Ly-Hartig N, McGinty RK, Fraterman S, Wilm M, Muir TW, Müller J. Histone H2A deubiquitinase activity of the Polycomb repressive complex PR-DUB. Nature. 2010;465:243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature08966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Wahab O, Gao J, Adli M, Dey A, Trimarchi T, Chung YR, Kuscu C, Hricik T, Ndiaye-Lobry D, LaFave LM, et al. Deletion of Asxl1 results in myelodysplasia and severe developmental defects in vivo. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2641–2659. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue D, Kitaura J, Togami K, Nishimura K, Enomoto Y, Uchida T, Kagiyama Y, Kawabata KC, Nakahara F, Izawa K, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes are induced by histone methylation-altering ASXL1 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4627–4640. doi: 10.1172/JCI70739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Li Z, He Y, Pan F, Chen S, Rhodes S, Nguyen L, Yuan J, Jiang L, Yang X, et al. Loss of Asxl1 leads to myelodysplastic syndrome-like disease in mice. Blood. 2014;123:541–553. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-500272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carbuccia N, Murati A, Trouplin V, Brecqueville M, Adélaïde J, Rey J, Vainchenker W, Bernard OA, Chaffanet M, Vey N, et al. Mutations of ASXL1 gene in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2009;23:2183–2186. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carbuccia N, Trouplin V, Gelsi-Boyer V, Murati A, Rocquain J, Adélaïde J, Olschwang S, Xerri L, Vey N, Chaffanet M, et al. Mutual exclusion of ASXL1 and NPM1 mutations in a series of acute myeloid leukemias. Leukemia. 2010;24:469–473. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdel-Wahab O, Adli M, LaFave LM, Gao J, Hricik T, Shih AH, Pandey S, Patel JP, Chung YR, Koche R, et al. ASXL1 mutations promote myeloid transformation through loss of PRC2-mediated gene repression. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:180–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilgendorf S, Folkerts H, Schuringa JJ, Vellenga E. Loss of ASXL1 triggers an apoptotic response in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Exp Hematol. 2016;44:1188–1196.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banaszak LG, Giudice V, Zhao X, Wu Z, Gao S, Hosokawa K, Keyvanfar K, Townsley DM, Gutierrez-Rodrigues F, Fernandez Ibanez MP, et al. Abnormal RNA splicing and genomic instability after induction of DNMT3A mutations by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2018;69:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexa A, Rahnenfuhrer J, Lengauer T. Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data by decorrelating GO graph structure. Bioinfomatics. 2006;22:1600–1607. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz Y, Wang ET, Airoldi EM, Burge CB. Analysis and design of RNA sequencing experiments for identifying isoform regulation. Nat Methods. 2010;7:1009–1015. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) methods. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller JN, Pearce DA. Nonsense-mediated decay in genetic disease: Friend or foe. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2014;762:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies C, Yip BH, Fernandez-Mercado M, Woll PS, Agirre X, Prosper F, Jacobsen SE, Wainscoat JS, Pellagatti A, Boultwood J. Silencing of ASXL1 impairs the granulomonocytic lineage potential of human CD34+ progenitor cells. Br J Haematol. 2013;160:842–850. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valletta S, Dolatshad H, Bartenstein M, Yip BH, Bello E, Gordon S, Yu Y, Shaw J, Roy S, Scifo L, et al. ASXL1 mutation correction by CRISPR/Cas9 restores gene function in leukemia cells and increases survival in mouse xenografts. Oncotarget. 2015;6:44061–44071. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris PE, Ralph P, Litcofsky P, Moore MA. Distinct activities of interferon-gamma, lymphokine and cytokine differentiation-inducing factors acting on the human monoblastic leukemia cell line U937. Cancer Res. 1985;45:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valledor AF, Borràs FE, Cullell-Young M, Celada A. Transcription factors that regulate monocyte/macrophage differentiation. J Leukoc Biol. 1988;63:405–417. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilliland DG. Hematologic malignancies. Curr Opin Hematol. 2001;8:189–191. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nauseef WM, Borregaard N. Neutrophils at work. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:602–611. doi: 10.1038/ni.2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owusu-Ansah E, Banerjee U. Reactive oxygen species prime Drosophila haematopoietic progenitors for differentiation. Nature. 2009;461:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature08313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tothova Z, Kollipara R, Huntly BJ, Lee BH, Castrillon DH, Cullen DE, McDowell EP, Lazo-Kallanian S, Williams IR, Sears C, et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 2007;128:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gingras MC, Lapillonne H, Margolin JF. TREM-1, MDL-1, and DAP12 expression is associated with a mature stage of myeloid development. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0161-5890(02)00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batliner J, Mancarelli MM, Jenal M, Reddy VA, Fey MF, Torbett BE, Tschan MP. CLEC5A (MDL-1) is a novel PU.1 transcriptional target during myeloid differentiation. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:714–719. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Negoro E, Yamauchi T, Urasaki Y, Nishi R, Hori H, Ueda T. Characterization of cytarabine-resistant leukemic cell lines established from five different blood cell lineages using gene expression and proteomic analyses. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:911–919. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Zhu CL, Nie CJ, Li JC, Zeng T, Zhou J, Chen J, Chen K, Fu L, Liu H, et al. Investigation of tumor suppressing function of CACNA2D3 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmieri C, Rudraraju B, Monteverde M, Lattanzio L, Gojis O, Brizio R, Garrone O, Merlano M, Syed N, Lo Nigro C, et al. Methylation of the calcium channel regulatory subunit α2δ-3 (CACNA2D3) predicts site-specific relapse in oestrogen receptor-positive primary breast carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:375–381. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wanajo A, Sasaki A, Nagasaki H, Shimada S, Otsubo T, Owaki S, Shimizu Y, Eishi Y, Kojima K, Nakajima Y, et al. Methylation of the calcium channel-related gene, CACNA2D3, is frequent and a poor prognostic factor in gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:580–590. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Price MA, Colvin Wanshura LE, Yang J, Carlson J, Xiang B, Li G, Ferrone S, Dudek AZ, Turley EA, McCarthy JB. CSPG4, a potential therapeutic target, facilitates malignant progression of melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:1148–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin W, Wu K, Li YZ, Yang WT, Zou B, Zhang F, Zhang J, Wang KK. AML1-ETO targets and suppresses cathepsin G, a serine protease, which is able to degrade AML1-ETO in t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2013;32:1978–1987. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang M, Lin X, Rowe A, Rognes T, Eide L, Bjørås M. Transcriptome analysis of human OXR1 depleted cells reveals its role in regulating the p53 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17409. doi: 10.1038/srep17409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher CL, Pineault N, Brookes C, Helgason CD, Ohta H, Bodner C, Hess JL, Humphries RK, Brock HW. Loss-of-function Additional sex combs like 1 mutations disrupt hematopoiesis but do not cause severe myelodysplasia or leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:38–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-230698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vainchenker W, Delhommeau F, Constantinescu SN, Bernard OA. New mutations and pathogenesis of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;118:1723–1735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-292102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inoue D, Matsumoto M, Nagase R, Saika M, Fujino T, Nakayama KI, Kitamura T. Truncation mutants of ASXL1 observed in myeloid malignancies are expressed at detectable protein levels. Exp Hematol. 2016;44:172–6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balasubramani A, Larjo A, Bassein JA, Chang X, Hastie RB, Togher SM, Lähdesmäki H, Rao A. Cancer-associated ASXL1 mutations may act as gain-of-function mutations of the ASXL1-BAP1 complex. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7307. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bejar R, Steensma DP. Recent developments in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2014;124:2793–2803. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-522136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gelsi-Boyer V, Brecqueville M, Devillier R, Murati A, Mozziconacci MJ, Birnbaum D. Mutations in ASXL1 are associated with poor prognosis across the spectrum of malignant myeloid diseases. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Damm F, Kosmider O, Gelsi-Boyer V, Renneville A, Carbuccia N, Hidalgo-Curtis C, Della Valle V, Couronne L, Scourzic L, Chesnais V, et al. Mutations affecting mRNA splicing define distinct clinical phenotypes and correlate with patient outcome in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;119:3211–3218. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-400994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Visconte V, Rogers HJ, Singh J, Barnard J, Bupathi M, Traina F, McMahon J, Makishima H, Szpurka H, Jankowska A, et al. SF3B1 haploinsufficiency leads to formation of ring sideroblasts in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120:3173–3186. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-430876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dolatshad H, Pellagatti A, Fernandez-Mercado M, Yip BH, Malcovati L, Attwood M, Przychodzen B, Sahgal N, Kanapin AA, Lockstone H, et al. Disruption of SF3B1 results in deregulated expression and splicing of key genes and pathways in myelodysplastic syndrome hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Leukemia. 2015;29:1092–1103. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ilagan JO, Ramakrishnan A, Hayes B, Murphy ME, Zebari AS, Bradley P, Bradley RK. U2AF1 mutations alter splice site recognition in hematological malignancies. Genome Res. 2015;25:14–26. doi: 10.1101/gr.181016.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]