Abstract

Available data indicate that dietary sodium (as salt) relates directly to blood pressure. Most of these findings are from studies lacking dietary data, hence it is unclear whether this sodium-blood pressure relationship is modulated by other dietary factors. With control for multiple non-dietary factors, but not body mass index, there were direct relations to blood pressure of 24-h urinary sodium excretion and the urinary sodium/potassium ratio among 4,680 men and women ages 40–59 (17 population samples in China, Japan, United Kingdom, United States) in the International Study on Macro/Micronutrients and Blood Pressure, and among its 2,195 American participants, e.g., 2 standard deviation higher 24-h urinary sodium excretion (118.7 mmol) associated with systolic blood pressure 3.7 mm Hg higher. These sodium-blood pressure relations persisted with control for 13 macronutrients, 12 vitamins, 7 minerals, and 18 amino acids, for both genders, older and younger, African-Americans, Hispanics, Whites and socioeconomic strata. With control for body mass index, sodium-blood pressure -- but not sodium/potassium-blood pressure -- relations were attenuated. Normal weight and obese participants manifested significant positive relations to blood pressure of urinary sodium; relations were weaker for overweight persons. At lower but not higher levels of 24-h sodium excretion, potassium intake blunted the sodium-blood pressure relation. The adverse association of dietary sodium with blood pressure is minimally attenuated by other dietary constituents; these findings underscore the importance of reducing salt intake for the prevention and control of prehypertension and hypertension.

Keywords: blood pressure, diet, hypertension, potassium, sodium

INTRODUCTION

Research evidence is available that habitual sodium (as salt, NaCl) intake is related directly to blood pressure (BP).1 For example, in the International Cooperative Study on Salt, Other Factors, and Blood Pressure (INTERSALT) involving 10,079 women and men ages 20–59 from 52 population samples in 32 countries, ecologic (cross-population) analyses (N=52) showed significant independent relations between sample 24-h median sodium (Na) excretion and sample median BP (systolic and diastolic, SBP, DBP), and prevalence of high BP. INTERSALT within-population analyses on individuals (N=10,079) showed a significant positive independent linear relation between 24-h urinary Na excretion and SBP.2–4 Dietary data were not collected in INTERSALT. Based on the extensive research data, expert groups have repeatedly made recommendations for population-wide lower Na intake; however, disagreements continue to prevail as to the importance of dietary salt.5–11

In the International Study on Macro/Micronutrients and Blood Pressure (INTERMAP) of 4,680 women and men ages 40–59 from 17 population samples in Japan, People’s Republic of China (PRC), United Kingdom (UK), and United States (USA), each participant collected two timed 24-h urine samples; study staff accrued detailed nutrition data from four in-depth 24-h dietary recalls.12, 13 Analyses here use these INTERMAP data to assess the quantitative relation to BP of 24-h urinary Na excretion and the urinary sodium to potassium (Na/K) ratio, and to evaluate whether consumption of multiple macro-micronutrients modulated these Na-BP relations.

METHODS

The analytic methods and data tables that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on request.

Population Samples, Field Methods, Dietary and Urinary Measurements

INTERMAP in 1996–1999 surveyed 4,680 men and women ages 40–59 years from 17 population samples in Japan (four samples), PRC (three), UK (two), and USA (eight).12 Participants were selected randomly from community or workplace population lists, arrayed into four age/gender strata. Each participant attended four clinic visits – two on consecutive days, two further visits on consecutive days on average three weeks later. Demographic and medical data, obtained by interviewer-administered questionnaire, included daily alcohol intake over the preceding 7 days, cigarette smoking status, attained educational level, physical activity, adherence to a special diet, dietary supplement use, use of antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs, and participant’s and family history of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and diabetes (DM). Height and weight were measured at two visits. Each participant provided two borate-preserved timed 24-h urine collections; aliquots were air-freighted frozen to the Central Laboratory (Leuven, Belgium) for biochemical analyses;12, 14 and to Imperial College London for proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.15 Dietary data were collected by trained certified interviewers using the in-depth multi-pass 24-h recall method; all foods, drinks, and supplements consumed in the previous 24 hours were recorded at each of the four visits.12, 13

Individuals were excluded if they did not attend all four visits; diet data were considered unreliable; energy intake from any 24-h dietary recall was below 500 kcal/day or greater than 5,000 kcal/day for women or 8,000 kcal/day for men; two urine collections were not available; other data were incomplete (215 individuals excluded).

Institutional ethics committee approval was obtained for each site; all participants provided written informed consent. This observational study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00005271.

Blood Pressure Method

Systolic and diastolic BP (first and fifth Korotkoff sounds) were measured twice at each visit by trained staff using a random-zero sphygmomanometer. A standard range of three cuff sizes was available (standard adult, large adult, and small adult/child). BP was measured twice at each study visit, for a total of eight measurements. Measurements were carried out on the right arm with participants seated for at least five minutes in a quiet room, with bladder emptied and no physical activity, eating, drinking, or smoking in the preceding 30 minutes.12

Statistical Methods

Diet recall data were converted into nutrients with use of country-specific nutrient composition tables, updated and standardized across countries by the Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota.13, 16 Measurements/person were averaged, for urinary excretions across the two collections, for BP and nutrients across the four visits.

Reliability as a measure of possible regression dilution bias for electrolyte excretion-BP relations -- expressed as the observed univariate regression coefficient as a per cent of the theoretical ‘true’ coefficient -- was estimated by the formula 1/[1+(ratio/2)]×100 for the averages of the two urinary Na and K values and of BP at the first two and last two clinic visits.17–19 The ratio is intra-individual variance divided by inter-individual variance, calculated from mean electrolyte excretions of the first and second urine collections, and from mean BP levels of the first and second two pairs of visits (to account for higher correlation between BP levels on consecutive days than on average of three weeks apart). Reliability was similarly estimated for body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2).

Because urinary data are considered more objective and have greater validity than self-reported dietary data for individuals, the urinary data were used here throughout. Associations of 24-h urinary Na and Na/K excretions with other nutrients were explored by partial correlation, adjusted for sample, age, gender; pooled across countries, weighted by sample size. Multiple 16-cell cross classification analyses based on quartiles of urinary Na and potassium (K) excretion, and multiple linear regression analyses were used to examine relationships of 24-h urinary Na and Na/K excretions to SBP and DBP, and their modulation by other dietary factors.

In the multiple linear regression analyses, several models were used, controlled successively for a larger number of possible confounders, non-dietary first, then also dietary. All models were computed without and with adjustment for BMI. Sensitivity analyses included stratification by socioeconomic status, ethnicity, age, gender, age and gender; censored normal regression to adjust for potential antihypertensive treatment bias;20 exclusion of participants with CVD and/or DM. After delineation of Na-BP relations controlled for non-dietary factors and BMI, each of many nutrients was assessed separately in regard to its possible modulation of the Na-BP relations, then further assessments were made as to whether multiple nutrients considered together modulated these Na-BP relations. Interactions were assessed for age, gender, and BMI, departures from linearity tested with quadratic terms. In the analyses for all 4,680 participants, regression models were by country and coefficients pooled across countries, weighted by the inverse of their variance; cross-country heterogeneity was tested by chi-square. Main findings are from 16-cell cross-classification analyses (quartiles of 24-h urinary Na and K), and from multiple linear regression analyses on BP differences with two standard deviation (SD) differences in 24-h urinary Na and Na/K excretions. Statistical tests were two-sided; two-tailed probability values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were done with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Data on the INTERMAP participants by country and overall are in Table S1 (Online Data Supplement), including urinary and dietary data. Average SBP was 118.9 mm Hg for all 4,680 participants, 118.6 mm Hg for the 2,195 US participants; average DBP 73.8 and 73.4 mm Hg respectively. For these two groups, mean Na excretions were 181.1 and 162.6 mmol/24-h; mean urinary Na/K ratios, 3.89 and 3.08; mean dietary Na intakes were 171.0 and 159.1 mmol/24-h; mean dietary K intake 70.2 and 74.6 mmol/24-h and dietary Na/K ratios were 2.70 and 2.32. For all 4,680 participants, partial correlations were 0.42 for urinary Na with dietary Na, 0.56 for urinary K with dietary K and 0.42 for urinary Na/K with dietary Na/K; for 2,195 US participants, these correlations were 0.46, 0.58, 0.50 respectively; all values were significant (P value <0.001).

Partial correlations for 24-h urinary Na with Na/K were 0.50 (all 4,680 participants) and 0.53 (2,195 US participants). Correlations were significant (P value <0.001) for Na with BMI, intake of total energy, total protein, total fats (direct), and total sugars (inverse). Urinary 24-h Na/K excretion was directly correlated with BMI, total fats, total mono-unsaturated fats, arachidonic acid, oleic acid, palmitoleic acid, palmitic acid, and stearic acid; inversely with dietary Mg, fiber, vitamin B6, vitamin C, calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), pantothenic acid, folate, total sugars, riboflavin, copper (Cu), non heme iron (Fe), total Fe, vitamin A, and beta carotene.

Univariate estimates of reliability of the average of two 24-h urinary sodium values (mmol/24-h) (similar for women and men) were 45.6% for all 4,680 participants, 42.1% for the 2,195 US participants. Findings were similar on reliability of the average of two 24-h urinary Na/K ratios. All BP and BMI reliability estimates were ≥90%.

Relation to Blood Pressure of 24-h Urinary Sodium Excretion

Multivariate 16-cell cross-classification analyses on the Na-BP relation (excluding BMI)

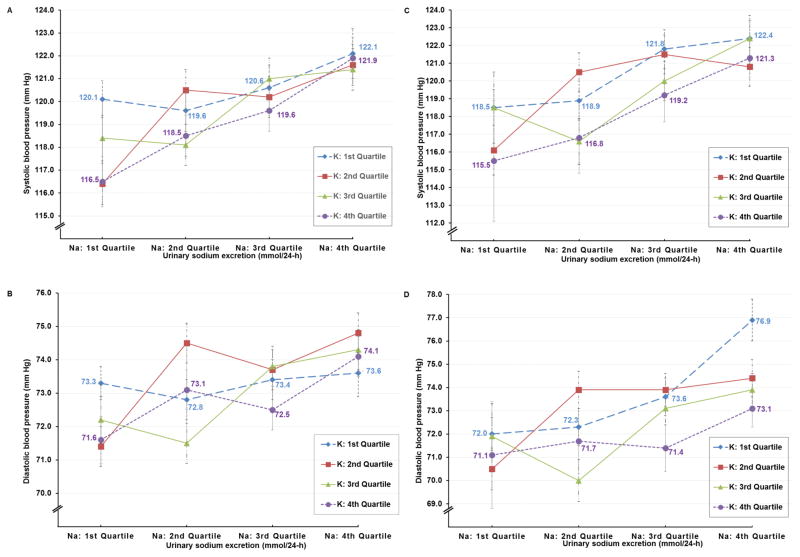

With 24-hr urinary Na and K excretions stratified into quartiles, mean levels of both electrolytes varied sizably across the 16 cells, e.g., for all 4,680 participants, Stratum 4 and Stratum 13, 24-hr urinary Na 108.2 and 279.5 mmol, K 78.4 and 31.9 mmol. With control for age, gender, and sample only, SBP and DBP were consistently higher for those in the highest compared to those in the lowest quartile of Na excretion (Figure S1). In four multivariate analyses, this finding was not attenuated with control for multiple possible non-nutrient and nutrient confounders. The four analyses entailed control of non-nutrient possible confounders and intake of: 1. ten macronutrients, alcohol, fiber, and caffeine (Table S2 and Figure 1); 2. twelve vitamins and alcohol (Table S3); 3. seven minerals and alcohol (Table S4); 4. eighteen dietary amino acids and alcohol (Table S5). In all these analyses, average values for BP remained similarly higher for persons in the fourth quartile (Q4) compared to those in the first quartile (Q1) of 24-h urinary Na excretion. Across the quartiles of 24-h Na, there was limited evidence that higher K intake blunted the Na-BP relation. Thus, for Na Q1 and K Q4 (Stratum 4) vs. Na Q1 and K Q1 (Stratum 1), SBP lower by 3.6 mm Hg, but with the other three comparisons, smaller differences: Na Q2 and K Q4 vs. Na Q2 and K Q1, SBP lower by only 1.1 mm Hg; Na Q3 and K Q4 vs. Na Q 3 and K Q1, SBP lower by only 1.0 mm Hg; Na Q4 and K Q4 vs. Na Q1 and K Q1, SBP lower by only 0.2 mm Hg (Figure 1A) - - a data pattern suggesting that the higher the 24-h urinary Na, the less the capacity of K intake to dampen the Na-BP relation.

Figure 1.

Mean blood pressure by quartiles of urinary sodium excretion adjusted for age, gender, and sample, education, physical activity, smoking status, history of cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus, family history of high blood pressure, use of special diet, use of dietary supplement, alcohol, animal protein, vegetable protein, cholesterol, total saturated fatty acids, total monounsaturated fatty acids, omega 3 fatty acids, omega 6 fatty acids, total trans fatty acids, total sugar, starch, total dietary fiber, caffeine: (A) systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) and (B) diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) for 4,680 participants; (C) systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) and (D) diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) for 2,195 US participants. Quartile cut-offs for urinary sodium (Na) excretion (mmol/24-h) were 145.96 (25th percentile), 187.12 (50th percentile), 236.47 (75th percentile) for men and 118.83, 153.40, 196.08 for women and quartile cut-offs for urinary potassium (K) excretion (mmol/24-h) were 41.58 (25th percentile), 53.60 (50th percentile), 69.94 (75th percentile) for men and 36.43, 46.48, 59.09 for women.

Multivariate 16-cell cross-classification analyses on the Na-BP relation (including BMI)

With control for BMI, the Na-BP relation was attenuated in 16-cell cross-classification analyses. Thus, per Table S2 with BMI not in the analyses, the four comparisons of Q4 Na vs. Q1 Na showed SBP higher by 2.0, 5.2, 3.0, and 5.4 mm Hg for Q4; with BMI also controlled in these analyses (Table S6), Q4 SBP differed from Q1 SBP by 0.3, 2.2, 0.5, and 1.9 mm Hg (Stratum 13 vs. 1, 14 vs. 2, 15 vs. 3, and 16 vs. 4 for all 4,680 participants). This attenuation of the Na-BP relation by BMI prevailed in multiple analyses.

Multiple linear regression analyses on the Na-BP relation (not including BMI)

Results from multiple linear regression analyses were consistent with the foregoing cross-classification findings on the Na-BP relation. Thus, for all 4,680 participants and for the 2,195 US participants, 2 SD higher urinary 24-h Na excretion (134.0 and 118.7 mmol per 24-h) was associated with SBP/DBP significantly higher, e.g., linear regression Model 3 (all 4,680) higher by 3.5/1.7 mm Hg (p<0.001) with control for multiple possible non-nutrient confounders, alcohol intake and 24-h urinary K (Table 1). With addition of 80 separate nutrients (one only at a time) to these models, the relation of Na to BP remained statistically significant and underwent only small quantitative variation. Findings remained similar in four further analyses, each including several nutrients together (Tables S2–S5); the Na-BP relation was not sizably modulated by any combination of multiple other nutrients, macro- or micro- (Table 2).

Table 1.

Relation of urinary 24-h sodium excretion 2 SD higher to systolic and diastolic blood pressure, linear regression analyses controlled for multiple possible non-dietary confounders

|

All INTERMAP participants (N=4,680), 2 SD = 134.01 mmol/24-h

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Systolic blood pressure

|

Diastolic blood pressure

|

||||||||||

| ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | Adjusted for BMI

|

ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | Adjusted for BMI

|

|||||

| ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | |||||||

| 1* | 3.01 | (2.08, 3.93) | <0.0001 | 0.07 | (−0.85, 0.99) | 0.88 | 1.43 | (0.82, 2.05) | <0.0001 | −0.25 | (−0.86, 0.36) | 0.43 |

| 2† | 2.50 | (1.58, 3.41) | <0.0001 | −0.17 | (−1.08, 0.73) | 0.71 | 1.23 | (0.61, 1.84) | <0.0001 | −0.34 | (−0.95, 0.27) | 0.27 |

| 3‡ | 3.45 | (2.45, 4.45) | <0.0001 | 0.80 | (−0.18, 1.78) | 0.11 | 1.71 | (1.04, 2.38) | <0.0001 | 0.15 | (−0.51, 0.82) | 0.65 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| US participants (N=2,195), 2 SD = 118.74 mmol/24-h | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Model | Systolic blood pressure

|

Diastolic blood pressure

|

||||||||||

| ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | Adjusted for BMI

|

ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | Adjusted for BMI

|

|||||

| ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1* | 3.36 | (2.17, 4.55) | <0.0001 | 0.32 | (−0.87, 1.51) | 0.60 | 1.38 | (0.57, 2.19) | <0.001 | −0.31 | (−1.14, 0.51) | 0.46 |

| 2† | 2.76 | (1.58, 3.94) | <0.0001 | 0.11 | (−1.08, 1.29) | 0.86 | 1.15 | (0.34, 1.96) | <0.01 | −0.37 | (−1.19, 0.45) | 0.38 |

| 3‡ | 3.73 | (2.45, 5.01) | <0.0001 | 1.11 | (−0.15, 2.38) | 0.08 | 1.75 | (0.87, 2.62) | <0.0001 | 0.25 | (−0.62, 1.13) | 0.57 |

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; ΔBP: blood pressure difference; CI: confident interval; P: P-value

Model 1: adjusted for age, gender, sample

Model 2: adjusted for Model 1 variables plus education, physical activity, smoking status, history of cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus, family history of high BP, use of special diet, use of dietary supplement, and alcohol

Model 3: adjusted for Model 2 variables plus urinary potassium

Table 2.

Relation of urinary 24-h sodium excretion 2 SD higher to systolic and diastolic blood pressure, linear regression analyses controlled for multiple possible non-dietary and dietary confounders (modulators)

| Model 3* | Systolic blood pressure

|

Diastolic blood pressure

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | |

| All INTERMAP participants (N=4,680), 2 SD = 134.01 mmol/24-h | ||||||

| A: macronutrients† | 3.07 | (2.02, 4.11) | <0.0001 | 1.69 | (0.99, 2.40) | <0.0001 |

| B: Vitamins‡ | 3.22 | (2.22, 4.24) | <0.0001 | 1.61 | (0.93, 2.30) | <0.0001 |

| C: Minerals§ | 3.05 | (2.03, 4.06) | <0.0001 | 1.54 | (0.85, 2.22) | <0.0001 |

| D: Amino acids|| | 3.24 | (2.19, 4.28) | <0.0001 | 1.73 | (1.03, 2.43) | <0.0001 |

| US participants (N=2,195), 2 SD = 118.74 mmol/24-h | ||||||

| A: macronutrients† | 3.24 | (1.89, 4.60) | <0.0001 | 1.70 | (0.77, 2.63) | <0.001 |

| B: Vitamins‡ | 3.32 | (2.01, 4.63) | <0.0001 | 1.61 | (0.71, 2.51) | <0.001 |

| C: Minerals§ | 2.99 | (1.68, 4.29) | <0.0001 | 1.45 | (0.55, 2.34) | 0.001 |

| D: Amino acids|| | 2.97 | (1.64, 4.29) | <0.0001 | 1.43 | (0.52, 2.33) | 0.002 |

SD: standard deviation; ΔBP: blood pressure difference; CI: confident interval; P: P-value

Model 3: adjusted for age, gender, sample, education, physical activity, smoking status, history of cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus, family history of high BP, use of special diet, use of dietary supplement, alcohol and urinary potassium

Animal protein, vegetable protein, cholesterol, total saturated fatty acids, total monounsaturated fatty acids, omega 3 fatty acids, omega 6 fatty acids, total trans fatty acids, total sugar, starch, total dietary fiber, caffeine

Vitamin A, beta-carotene, retinol, vitamin E, vitamin C, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12

Calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, heme iron, non-heme iron, copper, selenium

Alanine, arginine, aspartic acid, cysteine, glutamic acid, glycine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, threonine, tryptophan, tyrosine, valine

Multivariate linear regression analyses on the Na-BP relation (including BMI)

With inclusion of BMI in the multiple linear regression analyses, the strength of the Na-BP relation attenuated and ceased to be statistically significant (Table 1). This pattern of findings prevailed also with incorporation into these models of each of 80 macro/micronutrients considered singly and the four above cited combinations of nutrients. Accordingly, further analyses were done to assess the Na-BP relation separately in each of three BMI strata (normal weight, BMI<25 kg/m2; overweight, 25 ≤ BMI< 30 kg/m2; obese, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). In multivariate analyses for normal weight persons, 2 SD higher sodium intake was associated with SBP higher by 1.7 mm Hg (all 1,666 participants) and 2.1 mm Hg (614 Americans) (P values 0.08 and 0.06). Similarly, in these analyses for obese people, 2 SD higher sodium intake was associated with SBP higher by 2.1 mm Hg (all 1,073 participants) and 2.1 mm Hg (775 Americans) (P values 0.04 and 0.05). For overweight people, the Na-BP relation was weaker – – SBP higher by 0.5 mm Hg (all 1,861 participants) and 0.4 mm Hg (800 Americans) (P values 0.54 and 0.71).

Relation to Blood Pressure of 24-h Urinary Sodium to Potassium Ratio

For all 4,680 participants and for the 2,195 US participants, 2 SD higher 24-h Na/K ratio (3.3 and 2.5) was associated with SBP/DBP significantly higher without and with control for BMI, e.g., linear regression Model 2 (all 4,680) higher by 3.5/1.7 mm Hg (P<0.0001) controlled for multiple possible non-dietary confounders (Table 3). With addition one-by-one of 80 nutrients to these models, the relation of Na/K to BP remained statistically significant and underwent only small quantitative variation. Findings remained similar with inclusion of several nutrients together in four additional models; the Na/K-BP relation was not sizably modulated by these combinations of other nutrients (Table S7).

Table 3.

Relation of urinary 24-h sodium/potassium ratio to systolic and diastolic blood pressure, linear regression analyses controlled for multiple possible non-dietary confounders

|

All INTERMAP participants (N=4,680), 2 SD = 3.27

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Systolic blood pressure

|

Diastolic blood pressure

|

||||||||||

| ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | Adjusted for BMI

|

ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | Adjusted for BMI

|

|||||

| ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | |||||||

| 1* | 4.00 | (3.03, 4.98) | <0.0001 | 2.43 | (1.50, 3.37) | <0.0001 | 1.80 | (1.16, 2.44) | <0.0001 | 0.92 | (0.30, 1.54) | 0.003 |

| 2† | 3.52 | (2.55, 4.49) | <0.0001 | 2.15 | (1.21, 3.08) | <0.0001 | 1.67 | (1.03, 2.31) | <0.0001 | 0.88 | (0.26, 1.50) | 0.005 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| US participants (N=2,195), 2 SD = 2.45 | ||||||||||||

| Model | Systolic blood pressure

|

Diastolic blood pressure

|

||||||||||

| ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | Adjusted for BMI

|

ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | Adjusted for BMI

|

|||||

| ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | ΔBP | (95% CI) | P | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1* | 4.15 | (2.99, 5.30) | <0.0001 | 2.46 | (1.35, 3.58) | <0.0001 | 2.11 | (1.33, 2.90) | <0.0001 | 1.20 | (0.42, 1.97) | 0.002 |

| 2† | 3.45 | (2.37, 4.71) | <0.0001 | 2.13 | (1.00, 3.27) | <0.0001 | 1.96 | (1.16, 2.76) | <0.0001 | 1.18 | (0.39, 1.96) | 0.003 |

Model 1: adjusted for age, gender, sample

Model 2: adjusted for Model 1 variables plus education, physical activity, smoking status, history of cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus, family history of high BP, use of special diet, use of dietary supplement, and alcohol

The significant Na/K to SBP relation prevailed for all three weight strata in the analyses for all 4,680 people; for the normal weight and obese strata (but not the overweight stratum) for the 2,195 U. S. participants (Table S8).

DISCUSSION

Main findings here for all 4,680 INTERMAP participants and the 2,195 U.S. participants are the significant direct relationships to BP of both 24-h urinary Na and Na/K excretions in multivariate analyses without BMI in the models; with addition of BMI to the multivariate models, attenuation of the Na-BP relation, but not the Na/K-BP relation - - sizeable Na-BP relations for both normal weight and obese participants; no evidence of a J-shaped relation of Na or Na/K to BP; modest modulation (reduction) in strength of the Na-BP relation by K intake at lower levels of Na intake; no attenuation of the Na-BP or the Na/K-BP association by any of 80 other dietary variables considered one-at-a-time or in four multivariate combinations (macronutrients, vitamins, minerals, amino acids).

These findings on the direct relations in individuals from defined populations of Na and Na/K intake to BP prevailed for women and men, younger and older, across ethnic and socioeconomic strata. They are consistent with those of the INTERSALT Study2–4, 21 and go beyond them in demonstrating that these associations prevail with control for multiple other dietary factors and are not attenuated by multiple other dietary factors.

The finding that additions of BMI to the multivariate regression analyses produced attenuations of the Na-BP relationship may reflect i) higher food and hence higher Na consumption with higher BMI (partial correlation of 0.26 for Na-BMI), and ii) transfer statistically of the Na-BP association to BMI-BP. This may have happened since, unlike the nutrient variables, height and weight (used to formulate BMI) are measured with high precision, and well-measured variables may be preferentially selected for in multiple regression analyses (transfer bias22). Such attenuation by BMI of nutrient-BP relations has been encountered in prior analyses.17 In contrast, the Na/K ratio does not depend on the amount of food eaten (rather the quality of food) and is less correlated with BMI (partial correlation of 0.13), so is much less prone to such bias. Limitations of our study include its cross-sectional design, thus causal inferences are not possible, regression dilution bias related to imprecise measures, and the possibility of residual confounding. However, extensive efforts were applied to minimize those limitations (continuous observer training, repeated measurements of BP, standardized methods in dietary collection and BP measures, open-end questions, and on-going quality control).

The findings reported here on the Na-BP relationship add to a wealth of data from animal studies, epidemiological investigations and randomized controlled trials implicating Na intake in the rise of BP with age and the resultant high prevalence of raised BP and hypertension at middle to older ages.1–3, 17, 23, 24 While the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-like diet -- with increase in nutrient-dense intakes of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fat-free and low-fat dairy products, legumes, unsalted nuts and seeds, sea foods, unsaturated vegetable oils -- is effective in lowering BP25, the DASH-Na trial25 showed that Na reduction caused additional BP lowering beyond effects of DASH diet alone. Mechanisms and pathways to explain the independent and interacting effects of DASH diet and Na on BP remain to be elucidated. However, our findings on dietary Na and BP, consistent and reproducible across 17 samples and the four countries, have immediate practical implications for public health: the prevention and control of the adverse influences of dietary Na (salt) and Na/K on BP require major reductions in population-wide levels of salt intake; they cannot be accomplished only by substituting other dietary/lifestyle measures, however useful, including the DASH-type diet. Since the majority of salt ingested by Americans and the populations of many other countries comes from commercially prepared products, sizeable reductions by the food industry in the salt content of their products are essential to efforts to control the epidemic of raised BP worldwide.

In summary, the overall INTERMAP data and the U.S. INTERMAP data confirm the adverse relation of dietary Na and Na/K to BP, and show that multiple other dietary factors (macro- and micronutrients), including those influencing BP26, have at most only modest countervailing effects on the Na-BP relationship. To prevent and control the on-going epidemic of prehypertension and hypertension, major reductions are needed in the salt content of the food supply.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

Adverse BP levels, prehypertension and hypertension, continue to be prevalent at epidemic rates across U.S. population strata and worldwide. They are important causes of the still on-going epidemic of cardiovascular diseases. Excess habitual consumption of sodium (salt), derived largely from commercially processed food products, is an important factor in the etiopathogenesis of the unfavorable population BP patterns. Facilitating lower salt intake population-wide, including by accomplishment of sizeable reduction in the salt content of commercially prepared foods (e.g., breads), is a key strategy for prevention and control of the CVD epidemic.

WHAT IS NEW?

Blood pressure (BP) is directly related to sodium (Na) and sodium/potassium (Na/K) intake, measured objectively by timed 24-hour urine collections, and independent of other macro- and micro-nutrients

Other nutrients do not attenuate the relations of Na and Na/K to BP.

WHAT IS RELEVANT?

These results underscore and reaffirm the essentiality of population-wide reductions in Na and Na/K as pivotal for addressing the global epidemic of pre-hypertensive and hypertension and improving population health.

SUMMARY.

INTERMAP study data confirm the adverse relation of dietary Na and Na/K to BP, despite the intake of other favorable nutrients.

These findings on the Na-BP relationship add to a wealth of data from other studies implicating Na intake in the rise of BP with age, high prevalence rates of prehypertension/hypertenson, and high incidence rates of cardriovercular disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank all INTERMAP staff at local, national, and international centers for their invaluable efforts. A partial listing of these colleagues is given in Reference 13 below.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

The INTERMAP Study is supported by grants R01-HL50490 and R01-HL84228 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland, USA) and by national agencies in China, Japan (the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [A], No. 090357003), and the UK (a project grant from the West Midlands National Health Service Research and Development, and grant R2019EPH from the Chest, Heart and Stroke Association, Northern Ireland).

PE is Director of the MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health and acknowledges support from the Medical Research Council and Public Health England (MR/L01341X/1). PE acknowledges support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London, the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Health Impact of Environmental Hazards (HPRU-2012-10141), and UK MEDical BIOinformatics partnership (UK MED-BIO) supported by the Medical Research Council (MR/L01632X/1), and the UK Dementia Research Institute (UK DRI) at Imperial College London, funded by the Medical Research Council, Alzheimer’s Society and Alzheimer’s Research UK.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: This observational study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00005271.

DISCLOSURES

PE is a member of Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH) and a member of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Systematic Review on the Effects of Dietary Sodium and Potassium Intake on Health sponsored by US National Institutes of Health and US Centers for Disease Control. YW and PE are members of World Action on Salt and Health (WASH).

References

- 1.Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP, Meerpohl JJ. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2013;346:f1326. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott P, Dyer A, Stamler R. The INTERSALT study: Results for 24 hour sodium and potassium, by age and sex. INTERSALT co-operative research group. J Hum Hyperten. 1989;3:323–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott P, Stamler J, Nichols R, Dyer AR, Stamler R, Kesteloot H, Marmot M. INTERSALT revisited: Further analyses of 24 hour sodium excretion and blood pressure within and across populations. INTERSALT cooperative research group. BMJ. 1996;312:1249–1253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7041.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.INTERSALT: An international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24 hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion. INTERSALT cooperative research group. BMJ. 1988;297:319–328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6644.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. Committee on the Consequences of Sodium Reduction in Populations, Food and Nutrition Board, & Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. Sodium intake in populations: assessment of evidence. Washington, D.C: the National Academies Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mente A, O’Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, et al. Association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:601–611. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:612–623. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Engell RE, Lim S, Danaei G, Ezzati M, Powles J. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:624–634. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oparil S. Low sodium intake--cardiovascular health benefit or risk? N Engl J Med. 2014;371:677–679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1407695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cogswell ME, Mugavero K, Bowman BA, Frieden TR. Dietary sodium and cardiovascular disease risk - measurement matters. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:580–586. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1607161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobb LK, Anderson CAM, Elliott P, Hu FB, Liu K, Neaton JD, Whelton PK, Woodward M, Appel LJ. Methodological issues in cohort studies that relate sodium intake to cardiovascular disease outcomes a science advisory from the american heart association. Circulation. 2014;129:1173–1254. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stamler J, Elliott P, Dennis B, Dyer AR, Kesteloot H, Liu K, Ueshima H, Zhou BF. INTERMAP: Background, aims, design, methods, and descriptive statistics (nondietary) J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:591–608. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis B, Stamler J, Buzzard M, Conway R, Elliott P, Moag-Stahlberg A, Okayama A, Okuda N, Robertson C, Robinson F, Schakel S, Stevens M, Van Heel N, Zhao L, Zhou BF. INTERMAP: The dietary data--process and quality control. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:609–622. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaspar H, Dettmer K, Chan Q, Daniels S, Nimkar S, Daviglus ML, Stamler J, Elliott P, Oefner PJ. Urinary amino acid analysis: A comparison of iTRAQ(r)-LC-MS/MS, GC-MS, and amino acid analyzer. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:1838–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes E, Loo RL, Stamler J, et al. Human metabolic phenotype diversity and its association with diet and blood pressure. Nature. 2008;453:396–U350. doi: 10.1038/nature06882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schakel SF, Dennis BH, Wold AC, Conway R, Zhao LC, Okuda N, Okayama A, Moag-Stahlberg A, Robertson C, Van Heel N, Buzzard IM, Stamler J. Enhancing data on nutrient composition of foods eaten by participants in the INTERMAP study in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. J Food Compos Anal. 2003;16:395–408. doi: 10.1016/S0889-1575(03)00043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyer AR, Elliott P, Shipley M. Urinary electrolyte excretion in 24 hours and blood-pressure in the INTERSALT Study. Estimates of electrolyte blood-pressure associations corrected for regression dilution bias. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:940–951. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyer AR, Liu K, Sempos CT. Nutrient data analysis techniques and strategies. In: Berdanier CD, Dwyer J, Feldman EB, editors. Handbook of Nutrition and Food. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grandits GA, Bartsch GE, Stamler J. Method issues in dietary data analyses in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:211S–227S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.1.211S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobin MD, Sheehan NA, Scurrah KJ, Burton PR. Adjusting for treatment effects in studies of quantitative traits: Antihypertensive therapy and systolic blood pressure. Stat Med. 2005;24:2911–2935. doi: 10.1002/sim.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neal B. Best to ignore salt claims from studies using unsavoury data. [Accessed March 13, 2017];The Conversation. 2014 Aug 15; Avaliable at http://theconversation.com/best-to-ignore-salt-claims-from-studies-using-unsavoury-data-30563.

- 22.Zidek JV, Wong H, Le ND, Burnett R. Causality, measurement error and multicollinearity in epidemiology. Environmetrics. 1996;7:441–451. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott P, Walker LL, Little MP, Blair-West JR, Shade RE, Lee DR, Rouquet P, Leroy E, Jeunemaitre X, Ardaillou R, Paillard F, Meneton P, Denton DA. Change in salt intake affects blood pressure of chimpanzees: Implications for human populations. Circulation. 2007;116:1563–1568. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, Obarzanek E, Conlin PR, Miller ER, Simons-Morton DG, Karanja N, Lin Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. Dash-Sodium collaborative research group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:3–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, Bray GA, Vogt TM, Cutler JA, Windhauser MM, Lin PH, Karanja N. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. Dash collaborative research group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1117–1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan Q, Stamler J, Griep LMO, Daviglus ML, Van Horn L, Elliott P. An update on nutrients and blood pressure summary of intermap study findings. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23:276–289. doi: 10.5551/jat.30000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.