Abstract

The school playground provides an ideal opportunity for social inclusion; however, children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often struggle to engage in appropriate social interactions in this unstructured environment. Thus, they may spend recess time alone. The FRIEND Playground Program is a structured, play-based intervention aimed at improving social interactions of children with ASD and other social challenges during recess. The current research study employed a multiple baseline across participant design to systematically evaluate whether this intervention yields increased social engagement and initiations with peers during recess. Seven participants with ASD or other social challenges received 20 min of direct intervention from trained playground facilitators during school recess each day. Results suggest that the FRIEND Playground Program produced meaningful increases in social engagement and social initiations from baseline among participants with ASD and other social challenges.

Keywords: Social skills training, Autism spectrum disorders, Recess, Peer interaction skills

This research study provides:

Evidence supporting the use of naturalistic behavioral strategies during recess to increase social engagement of children with ASD and related social challenges

A description of specific behavioral strategies used to implement the FRIEND Playground Program in an elementary school setting

Observational data of children with social challenges and typically developing peer comparisons across an entire school year

Areas for future research on the FRIEND Playground Program

A defining feature of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is impairment in social communication (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Children with ASD are often included in general education settings to address social communication deficits through exposure to typically developing peers; however, they may not engage with their peers without appropriate supports (Harrower & Dunlap, 2001; Lee et al., 2007). For instance, children with ASD in general education classrooms are less accepted and have fewer reciprocal friendships than their typically developing classmates (Chamberlain et al., 2007; Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2010). Additionally, children with ASD frequently engage in solitary play, even in an environment rich with social opportunities (Anderson et al., 2004). Thus, it appears that mere inclusion in general education classrooms is not enough to facilitate meaningful social gains for children with ASD (Harrower & Dunlap, 2001).

In contrast, studies have shown that children with ASD can benefit from inclusion in general education settings when social skill interventions are provided (Bellini et al., 2007; DiSalvo & Oswald, 2002; Pierce & Schreibman, 1997). Bellini et al. (2007) found that children with ASD demonstrated improvement in social behaviors following the implementation of social skill interventions, especially when interventions were provided in a natural context. Further, generalization effects were observed to be stronger when social skills were taught in natural settings compared to analog settings (Bellini et al., 2007).

Lang et al. (2011) systematically reviewed playground interventions for children with ASD. Effective antecedent interventions on the playground included activity schedules and task correspondence training, environmental modifications, and priming (Machalicek et al., 2009; Owen-DeSchryver et al., 2008; Yuill et al., 2007). For some children with ASD, perseverative interests inhibited engagement in play with peers. Interventions designed to incorporate perseverative behaviors into socially appropriate games, and activities increased social motivation and social interactions between children with ASD and their peers. These increases were observed to generalize to other play activities (Baker et al., 1998; Koegel et al., 1987).

Peer-mediated interventions implemented during playground activities have been particularly effective for elementary school children with ASD (Lang et al., 2011). Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of training typically developing peers in the acceptance of ASD and the basic strategies of pivotal response treatment (PRT; Harper et al., 2008; Owen-DeSchryver et al., 2008). PRT, derived from the principles of applied behavior analysis (ABA; Koegel et al., 2006), is an evidence-based naturalistic intervention for individuals with ASD that incorporates shared control including following the child’s lead, natural reinforcers, and reinforcing behavior attempts. This approach targets pivotal areas (i.e., treatment targets that will result in progress in broader developmental areas), in order to increase responsiveness to social and environmental stimuli in natural settings. Pivotal areas include motivation, responsivity to multiple cues, self-initiations, and self-management (Koegel & Koegel, 2012; Koegel et al., 2006). Elementary school students with ASD have demonstrated increases in turn taking, social initiation, and social responses as a result of peer-mediated interventions that incorporate PRT strategies (Harper et al., 2008; Owen-DeSchryver et al., 2008). Although typically developing peers can play an integral role in social interventions for children with ASD, peer-training sessions can initially be time intensive, but may require less adult support over time. An alternative means of peer involvement in social interventions for ASD has been the inclusion of paraprofessionals who facilitate social interactions between children with ASD and their peers (Lang et al., 2011; Licciardello et al., 2008; Robinson, 2011).

Taken together, Bellini et al.’s (2007) meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions and Lang et al.’s (2011) systematic review of playground interventions for children with ASD have delineated avenues for future research. Bellini et al. (2007) reported that school-based social skill interventions for children with ASD have been minimally effective and made four suggestions for future research. Specifically, they suggested that interventions should (1) be provided frequently, (2) be conducted in natural setting, (3) match targeted social skills deficit, and (4) include measurement of treatment fidelity, as only 14 of the 55 studies reviewed in their meta-analysis measured fidelity of implementation. Lang et al. (2011) identified three primary types of existing playground interventions for children with ASD: (1) physical changes to environment, (2) peer-mediated interventions, and (3) paraprofessional training. Yet, these intervention strategies have not been incorporated simultaneously in a single intervention. Lang et al. also indicated that research on playground-based social skill interventions for children with ASD remains limited, and that additional research in this area is necessary. The program examined in the current evaluation incorporates various facets of previously examined playground interventions and addresses the suggestions of Bellini et al. (2007).

A natural setting such as the playground is an ideal environment for providing a social skills intervention designed using the principles of PRT. Specifically, by increasing a child’s motivation to participate in activities at recess, collateral benefits may be observed, including appropriate social behaviors like engagement with peers and social initiations with peers. However, playgrounds are generally unstructured, resulting in little social engagement for children with ASD (Gutierrez et al., 2007). A social skills intervention that addresses suggestions stemming from previous research and provides structure on school playgrounds using the principles of PRT and ABA may serve to effectively facilitate social interaction between children with ASD and their peers.

The Fostering Relationships in Early Network Development (FRIEND) Playground Program was developed to incorporate multiple intervention strategies in order to increase and improve the social interactions of students with ASD and related social challenges during recess (Dollin & Ober-Reynolds, 2004; Ober-Reynolds et al., under review). Interventionists with backgrounds in ASD and PRT were trained to facilitate interactions between participants and their typically developing peers, providing direct instruction regarding specific social skills as needed (e.g., sharing, turn taking, and giving a peer a compliment). Games and activities of interest to the participating students were added to the playground setting (e.g., board games, scavenger hunt activities, jump ropes, and sand toys) in order to increase motivation to engage in cooperative play activities. Peers were able to join or leave these structured activities as they desired. The playground facilitator provided in vivo support to students to increase social interactions between participating students and their peers.

The purpose of this initial program evaluation of the FRIEND Playground Program was to examine whether the implementation of this program resulted in increases in (1) social engagement of students with ASD and related social challenges with general education peers, and (2) social initiations from students with ASD or related social challenges toward general education peers.

Method

Participants

Participants were seven students attending a suburban elementary school in the southwestern USA. These students were chosen to participate in the FRIEND Playground Program because the school psychologist, with input from other school staff members, identified them as having significant social challenges and limited interactions with peers, especially during recess. These social challenges included difficulty initiating and/or maintaining peer interactions, difficulty engaging in play activities or conversation with peers, and/or limited to no interactions with peers. All students identified had been observed spending recess time alone or with adults only, or having negative or inappropriate interactions with peers during the previous school year. Examples of spending recess time alone include walking the perimeter of the playground alone, standing near the door to go inside, or following adults on the playground while talking about perseverative interests. Examples of negative or inappropriate peer interactions include a participant taking toys from other children in an attempt to get peers to chase him and pushing a peer when the peer did not do what the participant wanted. Participants had parental permission to participate in the program.

Characteristics of the participants are reported in Table 1. All participants received special education services, six under the category of autism and one under the category of emotional and behavior disorders (EBDs). Although the student with EBD did not have an autism diagnosis, he was identified to participate in the intervention program as he showed significant social challenges with peers and typically spent recess alone. Additionally, this student required significant academic, behavioral, and social educational supports, including a 1:1 paraprofessional. As the goal of the program was to increase social inclusion of students with social challenges, students were identified to participate based on their social behavior at recess rather than a specific diagnosis. All participants were included in the general education setting for at least 80% of the school day. Three participants had 1:1 paraprofessional support throughout the day, two participants (third grade participants) had one paraprofessional who supported both of them throughout the school day, and the other two students did not have any paraprofessional support. Paraprofessionals were occasionally present during recess to support students but typically were not present.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Participant | Grade | Age | Gender | Support | Educational diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Third | 8 | Female | 2:1 paraprofessional | Autism |

| 2 | Third | 8 | Female | 2:1 paraprofessional | Autism |

| 3 | Kindergarten | 5 | Male | 1:1 paraprofessional | Autism |

| 4 | First | 7 | Male | No support | Autism |

| 5 | First | 6 | Male | 1:1 paraprofessional | Emotional or Behavioral Disorder |

| 6 | Fourth | 9 | Male | 1:1 paraprofessional | Autism |

| 7 | Second | 7 | Male | No support | Autism |

Design

A concurrent multiple baseline across participant design (Kennedy, 2005) was used to examine whether implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program resulted in increased social engagement and more frequent social initiations from participants. Baseline data collection began at the same time for all students, but the start of intervention was staggered by 1 week across different grade levels. Specifically, the intervention was implemented first during the third grade recess, then during kindergarten and first grade recesses, and finally during fourth and second grade recesses. The intervention was implemented in this order based on the school’s preference and timing of the recess periods. Specifically, kindergarten and first grade recesses and fourth and second grade recesses were scheduled at overlapping times, so intervention began at the same time for students in the respective grades.

The FRIEND Playground Program

The FRIEND Playground Program is a social skills intervention designed for students with ASD and related social challenges. The intervention targets age-appropriate social skills through the provision of structured activities made available to all students on the playground (Dollin & Ober-Reynolds, 2004; Ober-Reynolds et al., under review). The FRIEND Playground Program was implemented daily during separate 20-min lunchtime recesses for kindergarten through fourth grades.

In the current evaluation of the FRIEND Playground Program, playground facilitators were trained interventionists employed by a local autism center (i.e., not school staff members), as the goal was to examine the effectiveness of the intervention prior to examining the feasibility of the program when implemented by school staff members. Playground facilitators had at least a bachelor’s level degree in psychology or a related field. Additionally, facilitators had experience working with individuals with ASD and were trained in the implementation of ABA-based interventions, including discrete trial teaching, PRT, and positive behavior supports. All playground facilitators had previous experience implementing these interventions as full-time in-home behavioral therapists for a minimum of 6 months and maximum of 2 years. Training of playground facilitators included core components of behavior skills training: instructions, modeling (via video), rehearsal, and feedback to mastery (Sturmey, 2008). Prior to implementing the program, each playground facilitator completed a 1-h training with the Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) from the autism center overseeing the program to discuss the specifics of the program. This didactic training included an overview of the program, detailed explanations of the six intervention strategies included in the program (described below), and role-playing exercises to practice each of the strategies. Across the school year, four playground facilitators implemented the intervention at the participating elementary school; however, only one playground facilitator was present on the playground at any one time. Playground facilitators communicated with each other weekly using a written communication log, by telephone, and/or in person. This ensured consistency of implementation for each participant and allowed for the discussion of activities of interest for each participant. Additionally, facilitators received weekly feedback from the BCBA overseeing the program. The BCBA met with facilitators for 10–30 min each week to review their fidelity of implementation, provide recommendations, and answer questions.

Structuring Activities

The playground facilitator provided several structured activities for all students on the playground. These activities were designed to increase the participants’ motivation to engage in play with typically developing peers, and were thus geared toward the participants’ interests. No students, including participants, were required to participate in the activities provided by the playground facilitators. Structured activities included any age-appropriate activities that allowed for social interaction and could be implemented on the playground. Examples of activities set up during recess included jump rope games, relay races, t-ball games, board games, and scavenger hunts.

Following the Student’s Lead

Child choice is an important component of targeting motivation through PRT (Koegel & Koegel, 2012; Koegel et al., 2006). Thus, when providing structure to playground activities, the playground facilitator followed the lead of the participants by asking them what they would like to play or observing their activity preferences. A formal preference assessment was not conducted, but preferences were continually monitored by observing the participants, asking the participants about their interests, and talking to educators about the interests of each participant. If participants were observed attempting to join or participate in an activity (e.g., watching other children play a game), the playground facilitator provided structure to the activity so that the participants would have the necessary support to participate successfully. For example, if a participant was watching his peers play soccer, but was unsuccessful in asking to join the game, the playground facilitator would prompt the student to ask a specific peer if he could join. The playground facilitator would then support the participant by prompting him to follow the rules of the game and reinforcing appropriate soccer behaviors. At times, the playground facilitator might introduce rules into the game to ensure all children were included in the activity (e.g., every person on a team must be passed the ball before the team can score). Another example of following the child’s lead occurred when a participant approached the slides on the playground. The playground facilitator set up “races” on the slides, during which two children waited for the facilitator to say “ready, set, go” and then raced to see who could get to the bottom first.

In some instances, the playground facilitator specifically set up games or activities related to the interests of the student with ASD in order to increase motivation to participate. In one instance, the facilitator set up a “bug search” activity for a student who had a specific interest in insects by hiding plastic bugs on the playground and having students work together to find them. Bugs were determined to be an interest for this child because he consistently talked about bugs and enjoyed reading books on bugs. Another example includes bringing board games out to recess for a participant who indicated he liked to play board games at home and during indoor recess. The facilitator identified a safe location for board games on the playground (i.e., where other children were not running or playing with balls) and facilitated turn taking in the activity as needed. Other utilized activities that were not previously present on the playground included crayons, colored pencils and paper for drawing, puzzles, plastic egg and spoon race game, and toy cars.

Facilitating Interaction between Students

The playground facilitator provided opportunities within structured activities for students to interact with one another at the level appropriate for the participant. This included setting up cooperative arrangements within an activity (Koegel et al., 2005; Werner et al., 2006), such as giving the participant all the materials for an activity to increase opportunities for social initiations and responses to peers. For example, when playing board games, the program facilitator would set a rule that each student must tell the next person “your turn” while passing the dice to him or her.

Additionally, at times, a peer was given all of the materials for an activity. For example, when an egg race game was set up, one child had all of the toy spoons and eggs so each child who wanted to participate, including the participant, had to ask this child for a spoon and egg to join the game. Facilitators would also create opportunities for children to interact during activities that typically involved parallel play. For example, when a participant was interested in swinging, the facilitator set up an opportunity for turn taking. The facilitator would prompt the peer to count as the participant swung. At a specific number, the participant and peer would switch roles.

Supporting the Student

Prompting was provided “as needed” to help participants initiate, respond, or appropriately engage in an activity. A prompt was considered to be needed if a participant failed to engage in appropriate social behavior in a situation where the participant was clearly expected to initiate or continue a social interaction with a peer. For example, prompting was provided when a participant failed to respond to a peer who asked the participant a question, failed to initiate an interaction with a peer when interest was evident (e.g., standing near a child playing), or the child failed to engage in a behavior to continue a social interaction (e.g., did not take his turn during a game).

Prompting strategies included verbal, model, and gestural prompts. Some examples of prompting strategies used by playground facilitators include modeling what a student should say to a peer (e.g., “Can I have a turn?”), providing a verbal instruction (e.g., “Go stand in line behind that student so you can take a turn with the jump rope”), or gesturing to indicate what a student should do (e.g., pointing to a peer who was talking to the student to direct his or her attention to the peer). Playground facilitators would implement the least intrusive prompt necessary depending on whether the participant had previously demonstrated the desired behavior. For example, one participant had previously shown the ability to pass the dice to the next person during a game but failed to pass the dice on one occasion. In this instance, the facilitator provided the least intrusive prompt first (i.e., gesture). If the participant did not demonstrate the target behavior after the least intrusive prompt, the facilitator would progress through more intrusive prompts (verbal, model, and physical; least to most prompting) as needed until the participant demonstrated the desired behavior. For target behaviors the participant had not previously demonstrated, more intrusive prompts were used initially to ensure the participant engaged in the target behavior. Prompts were gradually faded over time until the participant could engage in the target behavior independently. For example, the participant who attempted to initiate chase with other children by taking their toys was first provided a model prompt on how to ask a child to “chase me.” Then, the participant was given verbal reminders to ask the other child to “chase”. As the participant was successful, this prompt was faded to a gesture and then no prompts were provided to see if the participant would independently engage in the behavior of asking other children to chase him (i.e., most to least prompting).

Providing Reinforcement

The playground facilitator immediately provided praise and/or preferred items to participants and their general education peers contingent on appropriate social behaviors. The facilitator might praise students by saying “Great job giving your friend the dice so she could take a turn,” to provide labeled praise for displaying the specific appropriate social behavior and to pair praise with a natural reinforcer. Natural reinforcers (i.e., preferred items that are directly related to both the antecedent and target behavior; Koegel et al., 2006) were used whenever possible, including access to preferred items related to the activity in which the student was engaged. For example, when a participant complimented a peer during a game of basketball (e.g., saying “good job”), the playground facilitator immediately gave the participant the basketball. Another example would be if a participant appropriately waited for a turn in a game, the facilitator would provide labeled praise (e.g., “nice job waiting for your turn”) and provide the natural reinforcer of allowing the participant to take his turn.

In social skills interventions that include peers, it is important for interactions to be mutually reinforcing for both the student and his or her typical peers (Koegel et al., 2005). Thus, in addition to providing positive reinforcement for socially appropriate behaviors, the playground facilitator prompted participants and general education students to provide praise (e.g., high fives after a game) and tangible reinforcement (e.g., access to a preferred item) to each other for appropriate behavior. This helped all students learn to reinforce the positive social behaviors of their peers.

Prompting Appropriate Social Behaviors

If a participant engaged in inappropriate social behavior (e.g., taking a toy from another child; taking a turn out of turn in a game; making a mean comment to a peer; physical aggression toward a peer), the playground facilitator prompted the student to display the appropriate behavior and reinforced the student’s attempts. For example, if a participant grabbed a toy from a peer, the playground facilitator set up the opportunity again and prompted the student to display the socially appropriate behavior of requesting the item. The playground facilitator then prompted the peer to give the toy contingent on appropriate requests from the participant. Following the display of appropriate social behaviors, the playground facilitator immediately provided praise and access to preferred items to both the participant and the peer. As inappropriate social behaviors can be displayed by any child, the playground facilitator also prompted peers participating in structured activities to engage in appropriate behaviors as needed.

Measures

At baseline and throughout the implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program, direct observation was used to measure social engagement during cooperative activities and social initiations with peers. In particular, the duration of time participants spent engaged in cooperative activities with peers during recess (i.e., social engagement) and the frequency of social initiations toward peers during recess were observed. Data were collected using stopwatches to measure duration of time engaged with peers and total duration of the observation. Paper and pencil were used to tally social initiations and record duration of time engaged. The person collecting data stood as far away as possible while still being able to see and hear all interactions.

Engagement with Peers

Engagement with peers was defined as any time a participating student was interacting with a same-aged peer or peer group. Interactions included, but were not limited to, playing a game with peers, having a conversation with peers, or completing an activity with peers. This did not include completing a separate activity within close proximity to peers (i.e., parallel play), watching a game that peers were playing, or engaging in inappropriate activities (e.g., arguing). Engagement began after 5 s of a peer interaction and ended after 5 s of no peer interaction. Engagement with peers was converted from duration to a percentage score due to the fact that the observation was time varied.

Social Initiations

Social initiations were defined as any instance of a participant physically approaching or speaking to a same-aged peer or peer group with whom he or she had no interaction during the previous 5 s. An initiation was recorded even if the peer or peer group did not respond to the participant. Prompted social initiations were not recorded. Social initiations were converted from frequency to rate per min, as the length of each observation varied between 5 and 10 min.

Data Collection

Described below are the data collection procedures used during the baseline and intervention phases, followed by procedures for collecting peer comparison data and calculating interobserver agreement. Last, procedures for collecting social validity data are provided. Observation data were collected primarily by the BCBA overseeing the program and two additional master’s degree-level staff members from the autism center throughout the school year. On occasion, a playground facilitator who was not implementing the intervention collected observation data while another playground facilitator was implementing the intervention. Playground facilitators collected data during the baseline phase when the intervention was not being implemented.

Baseline Procedures

At the beginning of the school year, playground materials such as basketballs, jump ropes, and kickballs were available on the playground. The playground had a play structure that included a climbing apparatus and a slide, three basketball courts, a large open field with two baseball diamonds, several benches, and an open concrete area with a four-square court. Two school staff monitored the playground; however, no social skills intervention was provided. Any school staff members (one-on-one paraprofessionals) who had observed the program during the previous year were instructed not to provide the intervention while baseline data were collected. Additionally, the playground facilitators who implemented the intervention were not present during baseline, unless they were assisting in baseline data collection.

Baseline data were collected between 2 and 4 days per week for 2 weeks for participants 1 and 2 (4 total observations for each participant); 3 weeks for participants 3, 4, and 5 (7 to 10 observations for each participant); and 4 weeks for participants 6 and 7 (13 to 14 observations for each participant). The number of baseline observations per participant varied depending on the respective intervention start date and the attendance of participants on observation days.

Intervention Procedures

Data were collected on the two dependent measures for all participants and comparison peers in each grade for a minimum of 5 min at least one time per week for the duration of the school year (i.e., 34 weeks). During this time period, the intervention was provided daily, although data on target behaviors were only collected one time per week. For participants 1 and 2, the intervention occurred for 32 weeks. For participants 3, 4, and 5, the intervention occurred for 31 weeks and for participants 6 and 7, the intervention occurred for 30 weeks. Data collectors observed students during recess and collected data on target behaviors using a stopwatch, paper, and pencil while the intervention was implemented. Time of observation (between 5 and 10 min depending upon the length of recess), total time engaged with peers, and the frequency of social initiations (recorded using tally marks) were recorded.

Peer Comparison Observations

Peer comparison data were collected for the purpose of social validity (Kennedy, 2005). General education students at the same school, matched by grade, served as comparison peers. Different general education peers were examined during each observation (i.e., convenience sampling) because different general education students would engage in the structured activities each day. During each observation, a child of the same gender on the playground at the same time (i.e., same grade level) was selected. There were approximately 625 kindergartens through fourth grade students enrolled at this school; one grade level was present on the playground at a time during lunchtime recess. During the baseline phase, comparison peers were observed engaging in any playground activity (i.e., they did not have to be engaging in the same activity as a participant). During the intervention phase, comparison peers were engaging in the same activity as the participants when observation data were collected.

Interobserver Agreement

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was assessed across all observers during the baseline and intervention phases to ensure accuracy of data collection. IOA was calculated on 32% of all data collection sessions (30% of data collection sessions during baseline; 33% of data collection sessions during intervention), including peer comparison data. IOA for time engaged was calculated by dividing the shorter total duration recorded by the two observers by the longer total duration and multiplying by 100. IOA for social interactions was calculated by dividing the total number of agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements, and multiplying by 100 (Kennedy, 2005). IOA was 91.8% (range 0–100%) for time engaged and 88.3% (range 0–100%) for social initiations across observers. On three occasions during the school year, one observer recorded that an interaction and/or initiation occurred, whereas the other observer did not, resulting in 0% IOA for that observation. The next lowest IOA was 25% for social engagement and 33% for social initiation.

Fidelity of Implementation

During weekly visits to the school, the BCBA overseeing the program used fidelity of implementation checklist to monitor the implementation of the program and ultimately provide additional training and feedback for the playground facilitators as needed. Fidelity data were collected for each playground facilitator a minimum of one time per month and were collected on 25% of all intervention observations for each participant. The BCBA utilized 5-min partial interval data recording to collect and analyze fidelity of implementation data. This method allowed for the assessment of appropriate administration of the six strategies used to implement the FRIEND Playground Program. Fidelity of implementation was calculated by dividing the number of intervals during which the strategy was implemented appropriately by the total number of intervals and multiplying by 100.

Across the school year, the program was implemented with 94% fidelity (range 83–100%). When the program was not implemented with 100% fidelity, playground facilitators failed to provide opportunities within the activity for children to interact and/or immediately reinforce appropriate behavior of participants and peers. Setting up and maintaining the activity, following the lead of the participant, and supporting the participant as needed were consistently implemented throughout the school year. Providing prompts for appropriate social behaviors and setting up opportunities to practice socially appropriate behaviors as needed were often unnecessary within the 5-min interval and were marked as not applicable. When this occurred, these strategies were not included in fidelity calculations.

Social Validity

The social validity of the FRIEND Playground Program was assessed through the administration of a social validity questionnaire at the completion of the school year to the two school staff members who directly oversaw the program. School administrators were selected to complete the social validity form as they were the school staff members with the most familiarity with the program. The questionnaire (see Table 2) used a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Participants were asked to respond to five statements about the program.

Table 2.

Social validity questionnaire responses

| Question | Rater 1 | Rater 2 |

|---|---|---|

| The FRIEND Playground program benefited our students with ASD and other social challenges. | Strongly agree | Strongly agree |

| The FRIEND Playground Program benefited typically developing students at our school. | Agree | Agree |

| The FRIEND Playground Program required a reasonable amount of effort by school staff. | Strongly agree | Neutral |

| I am satisfied with the results of the FRIEND Playground Program. | Strongly agree | Strongly agree |

| I would recommend this intervention to other schools. | Strongly agree | Strongly agree |

Results

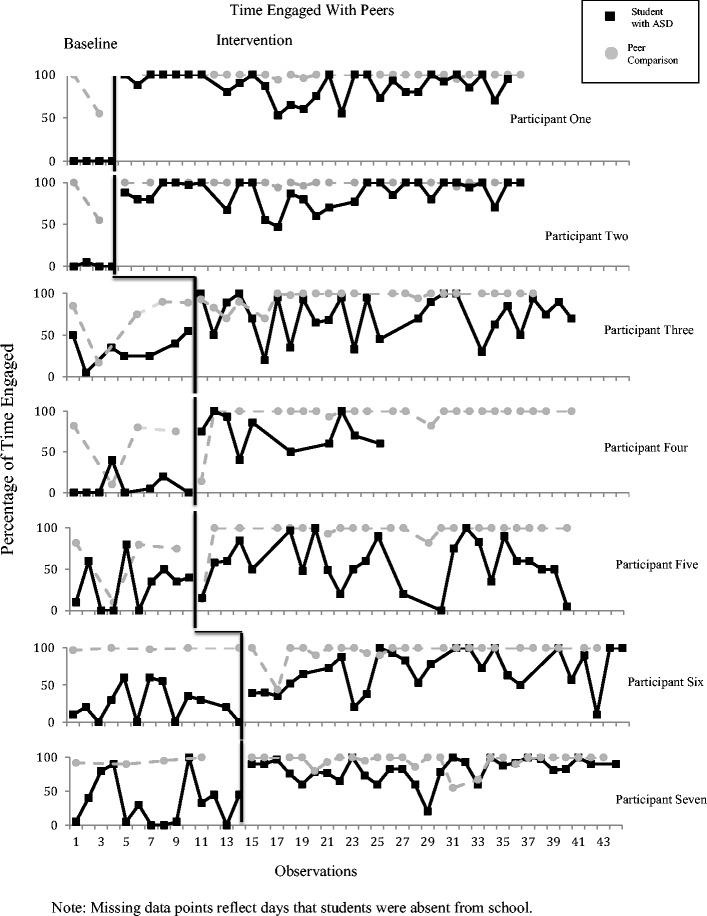

Time Engaged with Peers

Figure 1 shows the percentage of time participants and peer comparisons spent engaged with peers weekly from baseline to the end of the 34-week evaluation period. Based on visual analysis of the data, each of the seven participants demonstrated an increase in time spent engaged with peers during recess almost immediately after the intervention commenced. The data reflect interindividual and intraindividual variability across the school year, which will be described in detail below.

Fig. 1.

Time engaged with peers

During baseline, participants one and two (the third grade students) spent an average of 1% (range from 0 to 5%) and 0% of recess time engaged with peers, respectively. During intervention, participants 1 and 2 each spent an average of 87% (range 47–100% and 53–100%, respectively) of recess engaged with peers. Both participants demonstrated increases in time engaged with peers throughout the implementation of the program, and data between baseline and intervention did not overlap.

Participant 3, a kindergarten student, spent an average of 34% (range 5–55%) of recess engaged with peers during baseline and 73% (range 20–100%) of recess engaged with peers during the intervention. This participant’s time engaged with peers also increased immediately after implementation of the intervention; although variable over the school year with some overlap with his baseline data, his overall level of engagement during intervention was higher than at baseline.

Participant 4, one of the first grade participants, was engaged with peers, on average, for 8% (range 0–40%) at baseline. During the implementation of the intervention, participant 4 was engaged with peers for an average of 73% (range 40–100%) of recess. Participant 4 demonstrated an increase in time engaged with peers immediately following the implementation of the intervention, which remained stable throughout his participation in the intervention. His baseline and intervention data only overlapped on one occasion. Data collection for participant 4 was discontinued after 17 weeks because he moved to a different school. Participant 5, also a first grade participant, was engaged with peers 31% (range 0–80%) of recess during baseline and an average of 54% (range 0–100%) of recess during intervention. Participant 5’s engagement was variable over the course of the school year; however, engagement with peers occurred at a slightly higher level during intervention than during baseline.

Participant 6, a fourth grade student, was engaged with peers for an average of 25% (range 0–60%) of recess during baseline. During intervention, participant 6 was engaged with peers for an average of 69% (range 10–100%) of recess. The percentage of time engaged with peers increased slightly for this participant after the implementation of the intervention and continued to have an increasing trend over the duration of the intervention.

During baseline, participant 7, a second grade student, was engaged with peers for an average of 34% (range 0–100%) of recess. Participant 7 was engaged with peers, on average, for 82% (range 20–100%) of recess during intervention. This participant’s time engaged with peers increased immediately following the implementation of the intervention and, despite overlap between baseline and intervention, the level of engagement was higher during intervention than at baseline.

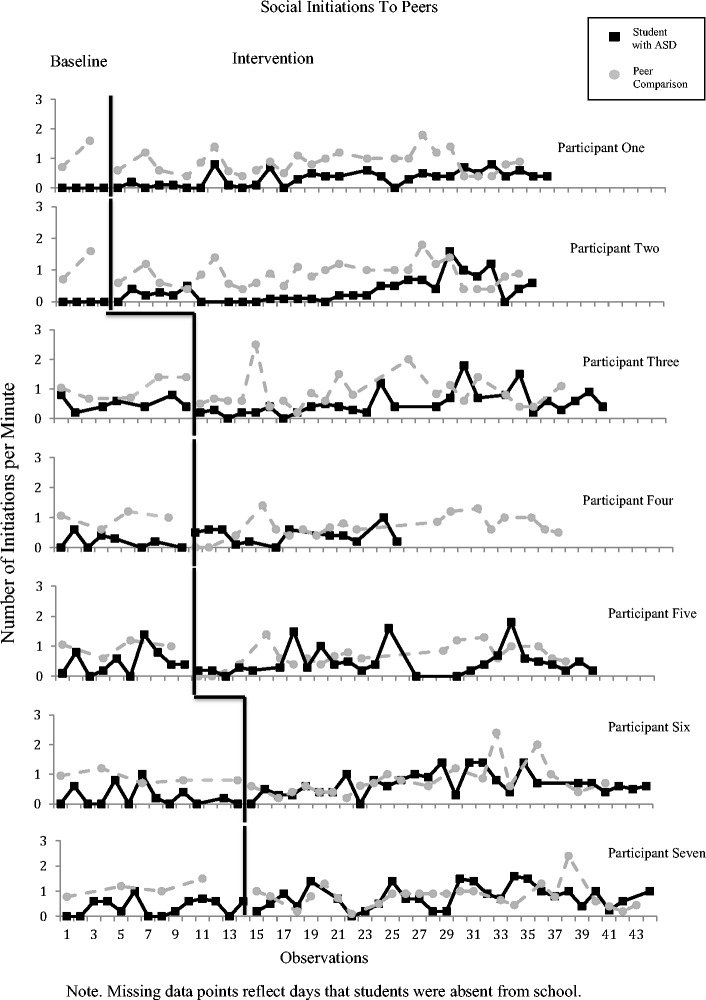

Social Initiations

Figure 2 shows the rate per min of social initiations made by participants and comparison peers from baseline to the end of the FRIEND Playground Program. Visual analysis of Fig. 2 reveals a small, gradual increase in social initiations for most participants across the school year, with overlap between data at baseline and intervention observed for all participants. All participants demonstrated variability in social initiations over the 34-week period.

Fig. 2.

Social initiations to peers

Participants 1 and 2 both demonstrated 0 social initiations during baseline. During intervention, participant 1 averaged 0.3 initiations per min (range 0–0.8) and participant two averaged 0.4 initiations per min (range 0–1.6). Both participants showed a slight increase in social initiations following the implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program with a slight increasing trend over the course of the program.

Participant 3 averaged 0.5 initiations per min during baseline (range 0.2–0.8) and intervention phases (range 0–1.8). The frequency of social initiations initially dropped after baseline but increased near the end of the program.

Participants 4 and 5 averaged 0.2 initiations per min (range 0–0.6) and 0.5 initiations per min (range 0–1.4) during baseline, respectively. During intervention, participant 4 averaged 0.4 social initiations per min (range 0–1.0) and participant 5 averaged 0.5 social initiations per min (range 0–1.8). Participant 4 demonstrated a slight immediate increase in social initiations following implementation of the intervention; however, data were variable across implementation of the program. Similar to participant 3, participant 5 showed an initial decrease in social initiations but eventually demonstrated an increasing trend in social initiations toward the end of the program.

Participant 6 averaged 0.2 social initiations per min at baseline (range 0–1.0) and 0.7 social initiations per min (range 0–1.4) during intervention. Participant 7 averaged 0.4 social initiations per min (range 0–1.0) at baseline and 0.8 social initiations per min (range 0–1.6) during intervention. Both participants 6 and 7 demonstrated a slightly increasing trend of social initiations following the implementation of the intervention.

Engagement and Social Initiations of Comparison Peers

Engagement with Peers

Across grade levels, comparison peers were engaged with their peers for an average of 78% (range 10–100%) of recess at baseline. During implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program, comparison peers engaged with peers for an average of 96% (range 14–100%) of recess. Data collected on comparison peers revealed a high level of variability, similar to the data collected on participants.

Visual inspection of Fig. 1 indicates that at baseline, participants engaged with peers less than did the comparison peers. At the completion of the school year, participants 1, 2, and 7 engaged with peers for a similar percentage of time as their same-aged comparison peers. The other participants showed some overlap with comparison peers in time engaged with peers over the course of the school year.

Social Initiations

Comparison peers also demonstrated a high number of social initiations during baseline averaging 1.0 initiation per min (range 0.6–1.6) across grade levels. Level of social initiations demonstrated by comparison peers remained similar throughout the entire implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program averaging 0.8 initiations per min (range 0–2.5). Similar to participants, comparison students demonstrated variability in social initiations throughout the program.

Visual inspection of Fig. 2 reveals that participants initiated with peers less often than did the comparison peers during baseline. At the completion of intervention, all participants, except participant 5, initiated with peers at a frequency similar to the same-aged comparison peers.

Social Validity

Two school administrators completed the social validity survey at the end of the FRIEND Playground Program; their responses are reported in Table 2. In the comments section, one administrator reported, “One of the highlights of my educational career has been my involvement with the FRIEND Playground Program.”

Discussion

Although many children with ASD are exposed to their peers during recess, elementary school playgrounds may lack sufficient structure and support to allow children with ASD to take advantage of this opportunity for inclusion, as has been observed in other inclusive settings (Harrower & Dunlap, 2001). The current research study utilized a multiple baseline design to examine the implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program, an adult-facilitated playground intervention that targets social engagement and social initiations in children with ASD and related social challenges using the principles of PRT. Findings suggest that the majority of participants experienced an increase from baseline in social engagement. Additionally, some participants experienced a slight increase from baseline in social initiations throughout the 34-week intervention period; however, this should be interpreted with caution due to the high level of variability in social initiations across participants.

Similar to previous research on elementary school students with ASD, participants in this research study were observed to engage and initiate with peers less frequently than comparison peers at baseline (Hauck et al., 1995). Participants in the current study were observed walking the perimeter of the playground, sitting alone, and watching peers play during recess prior to the implementation of the intervention. Also consistent with previous findings, several of the participants were observed being avoided or shunned by their peers during baseline (Sale & Carey, 1995). For example, one participant attempted to join a soccer game by walking onto the field. Instead of asking the participant if she wanted to play or including her in the activity, peers avoided her on the field and did not include her in the game. Another participant was observed attempting to initiate interactions with peers, and peers would walk away without responding.

Despite full integration with their same-aged peers during recess, participants did not demonstrate engagement with peers until playground facilitators provided direct social support. Altogether, these observations provide support to previous reports that mere exposure to typically developing peers is not sufficient to teach appropriate and meaningful social engagement skills to children with ASD, and that specialized support is needed to teach the skills required for social interactions (Kamps et al., 2002; Lang et al., 2011). Findings from the current study suggest that support for children with ASD and related social challenges may be effectively provided within that natural environment in the presence of typically developing peers, as opposed to the creation of superficial social situations for children to learn appropriate social skills. Social engagement was more stable for typically developing peers during intervention, which suggests that most children would benefit from some adult facilitation of social activities at recess.

Overall, participants’ time engaged with peers increased immediately following the implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program. Social initiations did not increase initially but slightly increased for some participants over the course of the program. This trajectory may reflect the fact that prompted social initiations were not recorded. Prompted social initiations were not recorded in order to control the number of variables being recorded and ultimately increase accuracy of data collection. During the initial implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program, most social initiations for participants were prompted. Prompting for social initiations was successfully faded (i.e., gradually moved from more intrusive prompts to less intrusive prompts over time until no prompt was provided) for several participants during the program, which may explain the observed increase in initiations toward the end of the program for some participants.

Data collected on time engaged with peers and social initiations showed a high level of variability across participants and comparison peers throughout the school year. This variability may be due to a number of factors, including peers present and conflicts with peers earlier that day or week. Parallel play was not included in the operational definition for social engagement in the current study. Therefore, social engagement may have been lower if participants engaged in an appropriate social activity that was parallel in nature (e.g., swinging, going down the slide, drawing with chalk). This may explain why some participants (e.g., participant 5) did not demonstrate significant increases in social engagement. Also, specific to social initiations, which showed a high level of variability for participants and peer comparisons, opportunities to initiate with peers may have varied depending on the type of playground activity available. For example, an activity where a child needs to ask for items (e.g., chalk) would provide increased opportunities for social initiation, whereas an activity like kickball may not provide as many clear opportunities for social initiation, even though children were socially engaged with one another. The observation that social initiations were highly variable for both participants and peer comparisons may indicate that this behavior is variable for even typically developing children on a day-to-day basis. Because the current study selected different peer comparisons at each observation, it remains unclear whether behavior is variable day-to-day for typically developing children or if the behavior is variable between typically developing children. This should be further examined to help identify reasonable and appropriate goals for children with social challenges related to social initiations.

The current study contributes meaningfully to the literature on playground interventions for children with ASD and related social challenges in several ways. First, the FRIEND Playground Program includes components of the primary types of playground interventions identified by Lang et al.’s (2011) systematic review of the literature. The physical environment was changed by modifying the activities and materials available at recess according to the interest of the participants. For instance, students participating in this program were provided board games, brooms, plastic bugs, and other objects of interest. Additionally, adult playground facilitators provided support to participants and their peers. Peers were provided with prompting and positive feedback from the playground facilitator during recess in order to facilitate the inclusion of participants in activities and conversations.

The FRIEND Playground Program was designed to be conducted solely in the natural environment of school playgrounds, where typical peer play interactions occur. Instead of training classmates outside of recess, adult playground facilitators taught social skills in the natural environment to students with ASD and their peers simultaneously. Any peer could receive support and instruction about interacting with student with social challenges by participating in activities structured by the playground facilitator. Additionally, peers who may not have been selected for a traditional peer-mediated intervention due to high frequency of problem behavior or low academic achievement were some of the most successful peers at interacting with the participants at recess. For example, the majority of one of the participant’s peers often spoke to her as if she was younger. In contrast, a same-aged boy interacted with her as he did his other peers. One of the teachers expressed surprise regarding these positive interactions, as the male peer often demonstrated problematic behaviors in the classroom and was not a student she expected to interact with the participant.

This study also examined many participants across multiple grades allowing for comparison of younger and older elementary-aged participants. Participants across the five examined grade levels demonstrated similar improvements in social engagement during the implementation of the intervention, with one exception. Participant 6’s increase in percentage of time engaged with peers was not as strong as was seen for the younger participants in this research study. By week 15, however, participant 6 demonstrated increases in time engaged with peers similar to the other participants. It is difficult to determine whether this seemingly unique trajectory was related to age or other specific characteristics of this participant.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite its strengths, this research study had several limitations. Many of the limitations stem from the fact that this was applied research conducted as the program was introduced within a school setting. Although best practices were used to evaluate the effectiveness of this program as it was implemented in an applied setting, a number of preexisting program characteristics limited the design of the study. For example, a multiple baseline design was used to control for maturation; however, baseline length was predetermined to ensure the program would begin in a timeframe that was acceptable to the school. Thus, a stable baseline was not achieved for all participants (e.g., participant 3 was observed to have an increasing trend at baseline for social engagement with peers). Additionally, data collection was scheduled in order to maximize opportunities to collect data during baseline (i.e., two to three times per week) and to ensure that treatment data collection was feasible during the remainder of the school year (i.e., at least one time per week). Future research should follow the same data collection schedule during baseline and intervention phases and should collect data for the same amount of time for each observation. Another limitation was that observers needed to be close enough to participants to hear and see interactions and, at times, participants indicated they were aware of observers. This may have impacted behavior of participants and comparison peers. Additionally, future research should adhere to guidelines for single-subject research as outlined by the What Works Clearinghouse (Kratochwill et al., 2010).

Data were collected throughout the academic year allowing for examination of the FRIEND Playground Program over an extended period of time. This data revealed both variability and stable levels of skills acquired from the program that may have been obscured had data been collected over a shorter period. However, the intervention was provided immediately following the baseline phase until the end of the school year and was never removed. It remains unknown whether the observed increases in social engagement would have been maintained in the absence of direct intervention. Future research should evaluate if changes in social behaviors are maintained after the intervention is removed.

All participants consistently used spontaneous phrase speech and were fully included in general education settings. The current findings may not generalize to students with more severe ASD and/or students in more restrictive educational settings. The effectiveness of the FRIEND Playground Program for children with ASD and other related disabilities at varying levels of functioning should be examined. The current intervention used only natural reinforcers which may not be sufficient to increase appropriate social behaviors of some children with ASD or other social challenges. In future research, the need for arbitrary reinforcers provided on a specific interval should be explored. A preference assessment was not conducted in the current evaluation and may be useful in future research and implementation of this program. Some participants in the program may benefit from additional social skills training such as formal instruction in an analog setting in addition to the FRIEND Program. For instance, participant 5 showed less of an increase in social engagement as compared to other participants. Perhaps by adding an intervention component such as social skills instruction, this participant would have demonstrated greater gains in social engagement at recess. Additionally, future research would benefit from full characterization of participants and comparison peers (e.g., assessment of cognitive and adaptive behavior). This information will aid professionals, parents, and other stakeholders in determining the appropriateness of the FRIEND Playground Program for their students.

Only one playground facilitator was present during each recess, despite the presence of several participants in some grades. The respective playground facilitator was therefore unable to provide social coaching every day to students in grades with multiple participants, resulting in some students receiving less intervention than others. Data regarding the exact amount of time the intervention was administered to each participant was not collected. Future research may examine the potential for a dose response to the intervention. In the current evaluation, playground facilitators communicated to one another through a communication log, telephone calls, and face-to-face meetings as needed to communicate participants’ preferred activities and any other relevant information. Future research should examine if more systematic communication between facilitators would increase the effectiveness of the program.

Although treatment fidelity was collected during the program, it was only collected during the treatment phase and interobserver agreement was not collected on this measure. Future research on the FRIEND Playground Program should include interobserver agreement and the collection of treatment fidelity data across all phases (Ledford &Wolery, 2013; Perepletchikova, 2014). Collection of interobserver agreement on fidelity of implementation data will determine if the measures of treatment fidelity are accurately defined or if refinement is necessary. Further, future research should examine generalization and maintenance of acquired skills. Data probes should be collected in other environments (e.g., lunchroom, classroom) to evaluate if social behaviors generalize to other environments, and maintenance probes should be conducted after the removal of the intervention to determine if the intervention effects maintain after intervention is removed.

The playground facilitators providing the intervention were highly trained interventionists from a highly regarded autism center. Implementing the FRIEND Playground Program in this manner may not be cost-effective for schools. Although the intervention was designed to be feasible for school staff members who have limited experience with ASD to implement, additional research is necessary to determine whether school staff members can successfully implement this program as part of their regular educational services and if more systematic training and evaluation of implementation and knowledge of the program is needed prior to implementation.

Several recommendations for future research were identified through informal reports about the program from school administrators, teachers, and parents. School administrators indicated a decrease in playground office referrals following implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program across all grade levels (not specific to participants). Several teachers reported that they spent less time discussing issues occurring on the playground, and a parent reported that her child received more birthday invitations from peers at school. Future research should analyze potential collateral benefits of the program for both participants with social challenges and general education peers. Additionally, future research should obtain social validity data from students participating in the program before and after implementation of the program by asking for their perspectives as well as the teachers and parents of these students to gain further insight into the social validity of this intervention.

Though measures of engagement and social initiations proved useful in quantifying peer interactions on the playground, these measures may not have captured the most significant social changes during the course of the program implementation. One participant with ASD in particular would engage with only one peer at baseline. When provided with supported opportunities to engage appropriately with a variety of peers, this student began to play cooperatively with a larger number of peers. Playground facilitators observed increases in peer initiations made toward the participant with ASD and this student’s responsivity to these initiations; however, these behaviors were not objectively measured. Future research should evaluate whether the FRIEND Playground Program is effective at increasing other socially appropriate behaviors including responsivity to peers and number of peers interacted with in addition to the outcomes measured in the current study. Additionally, data should be collected on parallel play in addition to cooperative play. It is possible that some participants who did not demonstrate increases in cooperative play may have shown increases in parallel play with peers.

Summary

Prior to the implementation of the FRIEND Playground Program, the seven participants demonstrated little to no social engagement or initiation with peers on the playground. Increases were observed in social engagement upon implementation of the program for most participants. Some participants were observed to show a slightly increasing trend in social initiations over the course of the program. The current findings suggest that the FRIEND Playground Program may be an effective playground-based social skills intervention for children with ASD and related social challenges. General education peers were included in the intervention through in vivo facilitation of play activities and social interactions, indicating that peers can be successfully included in naturalistic social skills interventions without prior training. These findings suggest that the use of naturalistic intervention strategies during recess can result in meaningful increases in social engagement between students with ASD and related disabilities and their peers.

Acknowledgments

This research study was presented as poster presentation at the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) Conference in Phoenix Arizona in May 2009. Readers interested in accessing the FRIEND manual should contact the corresponding author.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this program. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained to publish de-identified data from this program evaluation.

Conflict of Interest

Lori Vincent declares that she has no conflict of interest. Daniel Openden declares that he has no conflict of interest. Joseph Gentry declares that he has no conflict of interest. Lori Long declares that she has no conflict of interest. Nicole Matthews declares that she has no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A, Moore DW, Godfrey R, Fletcher-Flinn CM. Social skills assessment of children with autism in free-play situations. Autism. 2004;8:369–385. doi: 10.1177/1362361304045216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MJ, Koegel RL, Koegel LK. Increasing the social behavior of young children with autism using their obsessive behaviors. The Journal of the Association of for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1998;23:300–308. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.23.4.300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini S, Peters JK, Benner L, Hopf A. A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education. 2007;28(3):153–162. doi: 10.1177/07419325070280030401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain B, Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E. Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2007;37:230–242. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiSalvo CA, Oswald DP. Peer-mediated interventions to increase the social interaction of children with autism: consideration of peer expectancies. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2002;17(4):198–207. doi: 10.1177/10883576020170040201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dollin S, Ober-Reynolds S. The FRIEND program, fostering relationships in early network development. Phoenix, Arizona: Southwest Autism Research & Resource Center; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez A, Jr, Hale MN, Gossens-Archuleta K, Sobrino-Sanchez V. Evaluating the social behavior of preschool children with autism in an inclusive playground setting. International journal of special education. 2007;22:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Harper CB, Symon JBG, Frea WD. Recess is time-in: using peers to improve social skills of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:815–826. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrower JK, Dunlap G. Including children with autism in general education classrooms: a review of effective strategies. Behavior Modification. 2001;25(5):762–784. doi: 10.1177/0145445501255006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck M, Fein D, Waterhouse L, Feinstein C. Social initiations by autistic children to adults and other children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1995;25:579–595. doi: 10.1007/BF02178189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamps D, Royer J, Dugan E, Kravits T, Gonzalez-Lopez A, Garcia J, et al. Peer training to facilitate social interaction for elementary student with autism and their peers. Exceptional Children. 2002;68(2):173–187. doi: 10.1177/001440290206800202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CH. Single-case designs for educational research. Boston, MA: Pearson Education Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Dyer K, Bell LK. The influence of child-preferred activities on autistic children’s social behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1987;20:243–252. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Kogel LK. The PRT pocket guide: pivotal response treatment for autism spectrum disorders. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Openden D, Fredeen RM, Koegel LK. The basics of pivotal response treatment. In: Koegel RL, Koegel LK, editors. Pivotal response treatments for autism: communication, social, and academic development. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.; 2006. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Werner GA, Vismara LA, Koegel LK. The effectiveness of contextually supported play date interactions between children with autism and typically developing peers. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2005;30(2):93–102. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.30.2.93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W.R. (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation. Retrieved from What Works Clearinghouse website: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

- Lang R, Kuriakose S, Lyons G, Mulloy A, Boutot A, Britt C, Caruthers S, Ortega L, O’Reilly M, et al. Use of school recess time in the education and treatment of children with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5:1296–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford JR, Wolery M. Procedural fidelity: an analysis of measurement and reporting practices. Journal of Early Intervention. 2013;35:173–193. doi: 10.1177/1053815113515908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Odom SL, Loftin R. Social engagement with peers and stereotypic behavior of children with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2007;9(2):67–79. doi: 10.1177/10983007070090020401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Licciardello CC, Harchik AE, Luiselli JK. Social skills intervention for children with autism during interactive play at a public elementary school. Education and Treatment of Children. 2008;31:27–37. doi: 10.1353/etc.0.0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Machalicek W, Shogren K, Lang R, Rispoli M, O’Reilly MF, Franco JH, Sigafoos J. Increasing play and decreasing the challenging behavior of children with autism during recess with activity schedules and task correspondence training. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009;3:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2008.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owen-DeSchryver JS, Carr EG, Cale SI, Blakeley-Smith A. Promoting social interactions between students with autism spectrum disorders and their peers in inclusive school settings. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2008;23:15–28. doi: 10.1177/1088357608314370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F. Assessment of treatment integrity in psychotherapy research. In: Sanetti LMH, Kratochwill TR, editors. Treatment integrity: a foundation for evidence-based practice in applied psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Schreibman L. Multiple peer use of pivotal response training to increase social behaviors of classmates with autism: results from trained and untrained peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30(1):157–160. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SE. Teaching paraprofessionals of students with autism to implement pivotal response treatment in inclusive school settings using a brief video feedback training package. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2011;26(2):105–118. doi: 10.1177/1088357611407063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Fuller, E., Kasari, C., Chamberlain, B., & Locke, J. (2010). Social involvement of children with autism spectrum disorders in elementary school classrooms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(11), 1227–1234. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sale P, Carey DM. The sociometric status of students with disabilities in a full-inclusion school. Exceptional Children. 1995;62(1):6–19. doi: 10.1177/001440299506200102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmey P. Best practice methods in staff training. In: Luiselli JK, Russo DC, Christian WP, Wilcznski SM, editors. Effective practices for children with autism: educational and behavioral support interventions that work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, G. A., Vismara, L. A., Koegel, R. L., & Koegel, L. K. (2006). Play dates, social interactions, and friendships. In R. L. Koegel & L. K. Koegel (Eds.), Pivotal response treatments for autism communication, social, & academic development (pp. 199–213). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.

- Yuill N, Strieth S, Roake C, Aspden R, Todd B. Brief report: designing a playground for children with autistic spectrum disorders—effects on playful peer interactions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1192–1196. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]