Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is on the rise in the western world.1 The dynamic interplay between genetic susceptibility, the gut microbiome and host inflammatory reactions underlying IBD are still unclear. Shedding light onto these complex interactions in IBD, Chen et al.2 identified a key role for the negative immune regulator NLRP12 in shaping the composition of the gut microbiome and maintaining intestinal homeostasis. This finding, published in the most recent issue of Nature Immunology,2 can advance the development of much needed microbiome-based therapies for IBD patients.

It has been estimated that IBD affects over 3 million patients worldwide, particularly in western countries.1, 3 IBD includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease, and is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal cancers such as colorectal cancer.4 IBD is an immunologically driven, multifactorial disease with the complex involvement of genetics, environmental factors and gut microbiota.1, 5 While the exact cause is not well understood, it is accepted that dysbiosis—the imbalance of the gut microbiota toward colitogenic strains—is associated with IBD. This is of particular importance as recent advances point to an ever-increasing role of the microbiota in host immune regulation,5 and as shown by Chen et al.,2 vice versa. Microbiome-based therapies thus hold promise to advance treatment options not only for IBD patients but also perhaps other immune disorders.

The hallmark of IBD is a dysregulated inflammatory reaction to harmless gut commensals characterized by cytokine release and exacerbated immune signaling via NF-κB and STAT signaling pathways.4 These pathways can be regulated by members of the intracellular innate immune receptor family nucleotide-binding-domain leucine-rich-repeat receptors (NLRs), also known as NOD-like receptors, which are associated with IBD pathogenesis as both positive and negative regulators of inflammation.6, 7, 8 For example, the NLRP1 inflammasome is associated with reduced inflammation in experimental colitis, and the NLRP6 inflammasome has been demonstrated to suppress the growth of colitis-associated bacteria, while the role of NLRP3 remains controversial in IBD.6, 7, 8

NLRP12 is a negative regulator of NF-κB activation and inflammation9 and was identified as a suppressor of experimental colitis and tumorigenesis.10, 11 However, in contrast to NLRP6, which is known to regulate colonic microbiota by suppressing colitis-associated bacteria such as Prevotellaceae,12 the impact of NLRP12 on the colonic microbiota has been unclear to date. Jenny Ting’s group has now identified NLRP12 as a negative regulator of dysbiosis in experimental colitis by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria, thereby diminishing colonic inflammation.2

To show the importance of NLRP12 in UC, a form of IBD, Chen et al.2 profiled NLRP12 expression in a cohort of 10 pairs of monozygotic twins, with one healthy and one UC twin, as well as an additional non-twin UC patient cohort using published datasets from NCBI GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). In all patients with active UC, NLRP12 was downregulated compared to healthy subjects and compared to patients with inactive UC,2 suggesting a central role in UC. Using the dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) mouse model of experimental colitis13 in which DSS is administered through drinking water, they confirmed that NLRP12 deficiency considerably increased disease severity, corroborating the anti-inflammatory role of NLRP12 described previously.2, 10, 11 Intriguingly, the difference in disease severity between wild-type and NLRP12-deficient mice was only observed when mice were housed conventionally (that is, specific-pathogen free), as germ-free NLRP12-deficient and wild-type mice displayed a similar disease burden. This highlighted a key role of the microbiome of NLRP12-deficient mice in developing a more severe form of colitis compared to wild-type mice.

Sequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA indeed confirmed that NLRP12-deficient mice had an altered gut microbiome relative to wild-type mice; their microbiota was less diverse and composed of different bacterial communities. In particular, the abundance of the bacterial orders Bacteroidales and Clostridiales, as well as Lachnospiraceae, were reduced, while the abundance of Erysipelotrichaceae was increased.2 Remarkably, this microbiome profile was consistent over generations of different breeders in NLRP12-deficient mice, independent of housing conditions, diet and familial transmission, and, most importantly, resembled the microbiome of human IBD patients.14

To further delve into the mechanisms behind the severe colitis observed in NLRP12-deficient mice, the authors performed reciprocal transfer of microbiota between wild-type and NLRP12-deficient mice. This revealed that it was not solely the NLRP12-deficient microbiota that was responsible for the severity of the disease in NLRP12-deficient mice but that it was the microbiota in conjunction with the genetic deficiency that led to exaggerated colitis.2

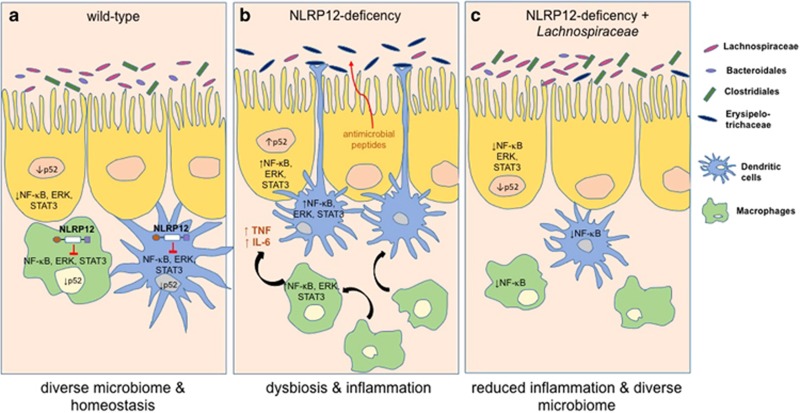

Notably, NLRP12-deficient mice could be rescued from this severe form of colitis when co-housed with wild-type mice, which allowed the exchange of microbiota by coprophagia (consumption of feces) and resulted in NLRP12-deficient mice adapting the microbiome of wild-type mice.2 This finding is crucial as it showed for the first time that increased susceptibility to colitis, due to NLRP12 deficiency, could be reversed by microbiome transfer. This could have implications for the treatment of IBD patients if future studies confirm that this can be translated to the human disease. Identifying the bacteria responsible for alleviating the disease was therefore imperative, and the authors could pinpoint their findings to the family of Lachnospiraceae, which is known to be implicated in IBD.14 When NLRP12-deficient mice were inoculated with 23 strains of Lachnospiraceae, intestinal inflammation and overall disease severity were reduced, and the composition of the endogenous microbiome shifted towards that of wild-type mice2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

NLRP12 regulates microbial diversity and maintains intestinal homeostasis. (a) Hematopoietic NLRP12 maintains intestinal homeostasis by promoting microbial diversity in favor of beneficial Lachnospiraceae, Bacteroidales and Clostridiales and by regulating immunological anergy of intestinal macrophages and dendritic cells. (b) NLRP12 deficiency leads to dysbiosis, a shift in the microbiota towards colitogenic Erysipelotrichaceae, supported by the release of antimicrobial peptides. The associated dysregulated inflammatory reaction mediated by both the hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic compartment is characterized by the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF and IL-6 and exacerbated immune signaling via NF-κB, ERK and STAT pathways. (c) Inoculation of Lachnospiraceae in NLRP12-deficient animals alleviates inflammation by restoring the diversity of the microbiome similar to that of wild-type mice. NLR, nucleotide-binding-domain leucine-rich-repeat receptors; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

To identify the cellular origin of NLRP12 expression that is responsible for shaping the gut microbiome, the authors undertook chimera experiments using irradiated wild-type and NLRP12-deficient recipient mice that were populated with either wild-type or NLRP12-deficient donor bone marrow. After analyzing the 16S rRNA of the microbiome of these chimeras, the authors identified the hematopoietic compartment as the source responsible for NLRP12-dependent regulation of intestinal bacterial diversity. Moreover, flow cytometry analysis revealed that lamina propria-derived macrophages and dendritic cell (DC) populations were elevated in NLRP12-deficient mice in vivo and reacted to cecal bacterial stimuli in vitro by upregulating inflammatory markers. This indicated that colonic macrophages and DCs of NLRP12-deficient mice had lost their anergic and anti-inflammatory properties, thus identifying NLRP12 as a key regulator of intestinal homeostasis.2

Lastly, the authors addressed the question of whether increased intestinal inflammation is the cause of dysbiosis. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy is a common treatment to reduce inflammation in IBD patients, but its effect on the microbiota is unknown. Not only did anti-TNF antibody and anti-interleukin (IL)-6R antibody treatment reduce the severe inflammation in NLRP12-deficient mice, but it also reversed the dysbiosis caused by NLRP12 deficiency, rendering the microbiome more reminiscent of that of wild-type mice by increasing the abundance of Bacteroidales and Clostridiales.2 This suggests that intestinal inflammation caused by NLRP12 deficiency enables a proinflammatory microbiome, which further drives inflammation, resulting in the development of a vicious inflammatory cycle.

In conclusion, Chen et al. identified a novel key role for NLRP12 in shaping the microbiota and maintaining gut homeostasis,2 which is in addition to its previously described anti-inflammatory function.10, 11 How NLRP12 promotes specific bacteria over others is yet to be shown.

While the study by Chen et al. advances our understanding of dysbiosis in experimental IBD, it also opens new avenues of research into how distinct regulators of the NLR family, such as NLRP6 and now NLRP12, facilitate microbiome homeostasis and differentially impact human IBD. Unlike NLRP12, NLRP6 is expressed in non-hematopoietic, epithelial compartments regulating distinct bacteria such as Prevotellaceae and TM7.12 Furthermore, the colitogenic microbiome of NLRP6-deficient mice was transferable to wild-type mice, which increased their susceptibility to severe colitis, which was not reported by Chen et al. for the NLRP12-deficient microbiome. Moreover, NLRP6 regulation of the microbiome was inflammasome-dependent, and inflammasome-derived IL-18 was demonstrated to be crucial for maintaining the gut microbiota,12 whereas the study by Chen et al. suggests that NLRP12-mediated microbiome regulation may be inflammasome-independent.

For IBD patients, the findings of Chen et al.2 offer hope for imminent microbiome-based therapies. Inoculation of Lachnospiraceae was shown to reverse inflammation in experimental colitis in NLRP12-deficient mice, which could be of potential therapeutic benefit for the subgroup of patients with reduced NLRP12 expression. Before this can be translated into therapy, however, more work is required to uncover the underlying immunomodulatory mechanisms of these protective bacteria.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12: 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wilson JE, Koenigsknecht MJ, Chou WC, Montgomery SA, Truax AD et al. NLRP12 attenuates colon inflammation by maintaining colonic microbial diversity and promoting protective commensal bacterial growth. Nat Immunol 2017; 18: 541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthakrishnan AN. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12: 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldner MJ, Neurath MF. Mechanisms of immune signaling in colitis-associated cancer. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 1: 6–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Mu L. An expanding stage for commensal microbes in host immune regulation. Cell Mol Immunol 2017; 14: 339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambetti LP, Mortellaro A. NLRPs, microbiota, and gut homeostasis: unravelling the connection. J Pathol 2014; 233: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TM, Leeth RA, Rothschild DE, Coutermarsh-Ott SL, McDaniel DK, Simmons AE et al. The NLRP1 inflammasome attenuates colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis. J Immunol 2015; 194: 3369–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corridoni D, Arseneau KO, Cifone MG, Cominelli F. The dual role of nod-like receptors in mucosal innate immunity and chronic intestinal inflammation. Front Immunol 2014; 5: 317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuncer S, Fiorillo MT, Sorrentino R. The multifaceted nature of NLRP12. J Leukoc Biol 2014; 96: 991–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki MH, Man SM, Vogel P, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. Salmonella exploits NLRP12-dependent innate immune signaling to suppress host defenses during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 385–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen IC, Wilson JE, Schneider M, Lich JD, Roberts RA, Arthur JC et al. NLRP12 suppresses colon inflammation and tumorigenesis through the negative regulation of noncanonical NF-kappaB signaling. Immunity 2012; 36: 742–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinav E, Strowig T, Kau AL, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Booth CJ et al. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell 2011; 145: 745–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassaing B, Aitken JD, Malleshappa M, Vijay-Kumar M. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Curr Protoc Immunol 2014; 104: Unit 15.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 13780–13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]