Abstract

Background and Purpose

Rescue of F508del‐cystic fibrosis (CF) transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), the most common CF mutation, requires small molecules that overcome protein processing, stability and channel gating defects. Here, we investigate F508del‐CFTR rescue by CFFT‐004, a small molecule designed to independently correct protein processing and channel gating defects.

Experimental Approach

Using CFTR‐expressing recombinant cells and CF patient‐derived bronchial epithelial cells, we studied CFTR expression by Western blotting and channel gating and stability with the patch‐clamp and Ussing chamber techniques.

Key Results

Chronic treatment with CFFT‐004 improved modestly F508del‐CFTR processing, but not its plasma membrane stability. By contrast, CFFT‐004 rescued F508del‐CFTR channel gating better than C18, an analogue of the clinically used CFTR corrector lumacaftor. Subsequent acute addition of CFFT‐004, but not C18, potentiated F508del‐CFTR channel gating. However, CFFT‐004 was without effect on A561E‐CFTR, a CF mutation with a comparable mechanism of CFTR dysfunction as F508del‐CFTR. To investigate the mechanism of action of CFFT‐004, we used F508del‐CFTR revertant mutations. Potentiation by CFFT‐004 was unaffected by revertant mutations, but correction was abolished by the revertant mutation G550E. These data suggest that correction, but not potentiation, by CFFT‐004 might involve nucleotide‐binding domain 1 of CFTR.

Conclusions and Implications

CFFT‐004 is a dual‐acting small molecule with independent corrector and potentiator activities that partially rescues F508del‐CFTR in recombinant cells and native airway epithelia. The limited efficacy and potency of CFFT‐004 suggests that combinations of small molecules targeting different defects in F508del‐CFTR might be a more effective therapeutic strategy than a single agent.

Abbreviations

- BHK cells

baby hamster kidney cells

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- hBE cells

human bronchial epithelial cells

- i

single‐channel current amplitude

- IBI

interburst interval

- MBD

mean burst duration

- MSD

membrane‐spanning domain

- NBD

nucleotide‐binding domain

- Po

open probability

Introduction

The genetic disease cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the ATP‐binding cassette transporter cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), an epithelial Cl− channel with complex regulation (Riordan et al., 1989; Gadsby et al., 2006; Ratjen et al., 2015). The molecular basis of most cases of CF is protein misfolding caused by the F508del mutation (Cheng et al., 1990). Misfolded F508del‐CFTR is recognized by the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) quality control system, ubiquitinated and destroyed by the proteasome (for review, see Lukacs and Verkman, 2012; Farinha et al., 2013b). Any F508del‐CFTR protein that escapes ER quality control and reaches the plasma membrane exhibits two further defects: plasma membrane instability (Lukacs et al., 1993) and defective channel gating (Dalemans et al., 1991). Thus, F508del‐CFTR disrupts profoundly CFTR function, leading to transepithelial fluid and electrolyte abnormalities (Frizzell and Hanrahan, 2012) and hence to organ dysfunction (Ratjen et al., 2015).

In the search for drugs to rescue the plasma membrane function of CFTR, two classes of small molecules have been identified. First, CFTR correctors, which traffic mutant proteins to the plasma membrane (Lukacs and Verkman, 2012). Second, CFTR potentiators that enhance greatly mutant channel gating (Cai et al., 2011). When tested alone, neither CFTR correctors, such as lumacaftor (VX‐809; Van Goor et al., 2011) nor CFTR potentiators, such as ivacaftor (VX‐770; Van Goor et al., 2009) had clinical benefit for CF patients with the F508del mutation (Clancy et al., 2012; Flume et al., 2012). By contrast, chronic co‐administration of lumacaftor and ivacaftor to CF patients homozygous for the F508del mutation increased modestly lung function, but improved markedly disease stability (Wainwright et al., 2015), leading to the approval of lumacaftor–ivacaftor combination therapy.

An attractive alternative approach to combination therapy for F508del‐CFTR would be the use of a single small molecule that corrects both the protein processing and channel gating defects of F508del‐CFTR. These dual‐acting small molecules are termed CFTR corrector‐potentiators (Kalid et al., 2010). Interestingly, the first CFTR corrector‐potentiator, the pyrazole VRT‐532 (Van Goor et al., 2006), was identified serendipitously (Wang et al., 2006). Previous work suggests that there are at least two types of CFTR corrector‐potentiators. Some dual‐acting small molecules promote F508del‐CFTR delivery to the plasma membrane, but do not potentiate robustly channel gating when added acutely. Instead, these agents, which include lumacaftor and its analogue C18 (VRT‐534) enhance channel activation by cAMP‐dependent phosphorylation (Eckford et al., 2014). Other dual‐acting small molecules, such as the cyanoquinolines (Phuan et al., 2011) independently correct the F508del‐CFTR trafficking defect and acutely potentiate channel gating. The mechanism of action of this latter class of compounds is not well understood.

Here, we investigated the mechanism of action of the dual‐acting small molecule CFFT‐004 (Chiang and Ghosh, 2010), synthesized by EPIX Pharmaceuticals Inc., a CFTR corrector‐potentiator with independent F508del‐CFTR corrector and potentiator activities. With the Ussing chamber and patch‐clamp techniques, we analysed the effects of correction and potentiation with CFFT‐004 on the plasma membrane stability and channel gating defects of F508del‐CFTR. To probe the mechanism of action of CFFT‐004, we used the F508del‐CFTR revertant mutations G550E and R1070W (deCarvalho et al., 2002; Thibodeau et al., 2010), and to explore specificity, we studied A561E, another class II‐III‐VI CF mutation (Veit et al., 2016) with defects closely comparable to those of F508del‐CFTR (Mendes et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2014). Our results demonstrate that CFFT‐004 has differential effects on F508del‐CFTR, but fails to rescue A561E‐CFTR. It rescues F508del‐CFTR channel gating better than it improves protein processing, but is without effect on channel stability.

Methods

Cells and cell culture

For biochemical and functional studies of recombinant CFTR, we used baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells stably expressing wild‐type human CFTR, the CF mutants F508del and A561E and the revertant mutations G550E, R1070W and G550E‐R1070W (Roxo‐Rosa et al., 2006; Farinha et al., 2013a); mouse mammary epithelial (C127) cells stably expressing wild‐type human CFTR (Marshall et al., 1994), Fischer rat thyroid (FRT) epithelial cells stably expressing F508del human CFTR (Figure 1, 1F12, M470 cell line; Bridges et al., 2013; Figure 5, Hughes et al., 2008) and CHO cells stably expressing F508del murine CFTR. The cells were generous gifts of CR O'Riordan (Genzyme; C127 cells), RJ Bridges (Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science; FRT cells), LJV Galietta (Instituto Giannina Gaslini; FRT cells) and BJ Wainwright (University of Queensland; CHO cells). Cells were cultured and used as described previously (Sheppard and Robinson, 1997; Lansdell et al., 1998a; Zegarra‐Moran et al., 2002; Hughes et al., 2008; Schmidt et al., 2008) with the exceptions that (i) FRT cells used for Figure 1 were seeded on Snapwell filter inserts (cat. no. 3801, Corning, NY, USA) and grown for at least 7 days before use and (ii) the selection agent for F508del murine CFTR expressing CHO cells was methotrexate (AAH Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Coventry, UK). For functional studies of native CFTR, we used primary cultures of human bronchial epithelial (hBE) cells homozygous for F508del‐ or A561E‐CFTR. hBE cells were either expanded from frozen stock generously supplied by SH Randell (University of North Carolina) and differentiated at an air‐liquid interface (ALI) (Neuberger et al., 2011) or isolated, cultured and ALI differentiated as described previously (Awatade et al., 2015). To promote the plasma membrane expression of F508del‐ and A561E‐CFTR, cells were incubated at 26–27°C for 24–72 h or treated with small molecules for 24 h at 37°C prior to use (Denning et al., 1992; Mendes et al., 2003; Van Goor et al., 2011; Meng et al., 2017). When testing the effects of chronic drug treatments on F508del‐ and A561E‐CFTR, the FBS concentration of media was reduced to 1% (v·v−1). In patch‐clamp experiments, to remove drugs from the extracellular solution, small molecule‐treated cells were thoroughly washed with drug‐free physiological solutions before experiments were commenced. However, the maximum period these cells were left in drug‐free solution before study did not exceed 30 min. The single‐channel behaviour of wild‐type human CFTR in excised inside‐out membrane patches from different mammalian cells is equivalent (Chen et al., 2009).

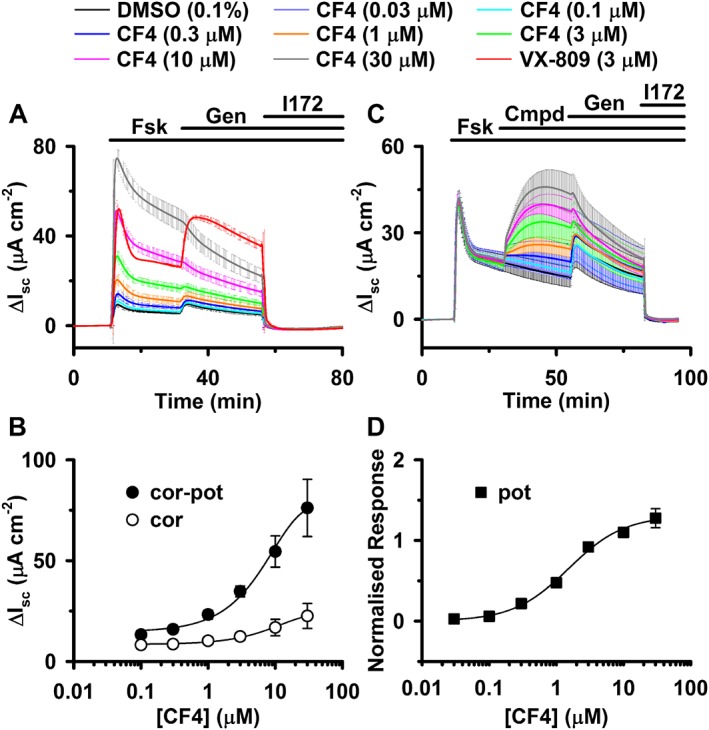

Figure 1.

CFFT‐004 rescues F508del‐CFTR function in recombinant FRT epithelia by acting both as a CFTR corrector and as a CFTR potentiator. (A, C) Ussing chamber recordings of Isc from FRT epithelia expressing F508del‐CFTR acquired at 37°C are shown. Prior to commencing the recordings, in (A), F508del‐CFTR expressing epithelia were treated for 24 h at 37°C with either the vehicle DMSO (0.1% v·v−1), CFFT‐004 (0.1–30 μM) or the CFTR corrector lumacaftor (VX‐809; 3 μM) as indicated, whereas in (C), they were pretreated with lumacaftor (VX‐809; 3 μM) for 24 h at 37°C. In (A) and (C), during the indicated periods, forskolin (Fsk; 10 μM), genistein (Gen; 20 μM) and CFTRinh‐172 (I172; 20 μM) were added to the solutions bathing the apical and basolateral membranes, and in (C), during the indicated period, either the vehicle DMSO (0.1% v·v−1) or CFFT‐004 (0.03–30 μM) were added to the apical solution as indicated (Cmpd). In both (A) and (C), pre‐forskolin baseline Isc was subtracted from all Isc recordings before data were averaged. (B) Relationship between CFFT‐004 concentration and change in Isc for the peak forskolin response and the CFTRinh‐172‐sensitive current used to determine EC50 values for CFTR correction and potentiation and CFTR correction alone, respectively. (D) Relationship between CFFT‐004 concentration and normalized maximum acute response following CFFT‐004 addition used to determine the EC50 value for CFTR potentiation. The normalized maximal acute response to CFFT‐004 represents the slope corrected maximal acute response to CFFT‐004 normalized to the forskolin‐stimulated ΔIsc at the time of CFFT‐004 addition. In (A) and (C), data are means ± SD (n = 2), whereas in (B) and (D), data are means ± SD (n = 4); error bars are smaller than symbol size except where shown. In (B) and (D), the continuous lines show the fit of the Hill equation to mean data using a Hill coefficient (H) of 1.

Figure 5.

Effects of CFFT‐004 on the stability of F508del‐CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− currents. (A) Representative Ussing chamber recordings of F508del‐CFTR showing the effects of correction with C18 and CFFT‐004 on CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− currents. F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in the presence of either C18 (5 μM) or CFFT‐004 (10 μM) without reducing the FBS concentration of media. Fifteen minutes prior to mounting FRT epithelia in Ussing chambers (i.e. t = 0 h – 15 min), they were treated with cycloheximide (50 μg·mL−1), added to both the apical and basolateral solutions. At the indicated times, FRT epithelia were activated with forskolin (Fsk; 10 μM), potentiated with ivacaftor (VX; 1 μM) and inhibited by CFTRinh‐172 (I172; 10 μM); continuous lines indicate the presence of different compounds in the apical solution; cycloheximide (50 μg·mL−1) was present in the apical and basolateral solutions during Isc recordings. Data are normalized to baseline current so that ΔIsc represents the change in transepithelial current after CFTR activation by forskolin. The vertical lines denote the forskolin‐stimulated CFTR‐mediated Isc (IFsk) and the total CFTR‐mediated Isc (ITot). For representative CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− currents of C18‐ and CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR recorded at different times after cycloheximide treatment, see Supporting Information Figure S2. (B and C) Rt and magnitude of forskolin‐stimulated CFTR‐mediated Isc (IFsk) expressed as a percentage of the total CFTR‐mediated Isc (ITot) (i.e. IFsk/ITot) for F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia pretreated with either C18 (5 μM) or CFFT‐004 (10 μM) for 24 h at 37°C prior to study. Fifteen minutes prior to t = 0 h, FRT epithelia were treated with cycloheximide (50 μg·mL−1) as described in (A). (D, E) Magnitude of forskolin‐stimulated CFTR‐mediated ΔIsc and the total CFTR‐mediated ΔIsc (i.e. the ivacaftor potentiated ΔIsc) for C18‐ and CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR at different times after cycloheximide treatment. (F) Magnitude of the absolute Isc prior to CFTR activation for C18‐ and CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR at different times after cycloheximide treatment. (G) Magnitude of the residual CFTR‐mediated Cl− current determined using CFTRinh‐172 (10 μM) for C18‐ and CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR at different times after cycloheximide treatment. For definition of residual CFTR‐mediated Cl− current (IRes), see Supporting Information Figure S2E. Positive values of IRes indicate that the CFTRinh‐172‐inhibited current did not fall below the value of basal current prior to F508del‐CFTR stimulation with forskolin. Negative values of IRes indicate that the CFTRinh‐172‐inhibited current has decreased below the value of basal current prior to F508del‐CFTR stimulation with forskolin. In (B–G), data are means ± SEM (C18, n = 6; CFFT‐004, n = 6, except t = 4 h, where n = 5); *, P < 0.05 versus C18 control, unpaired t‐test; †, P < 0.05 versus control at time 0 h, one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's post test.

Western blotting

To assess the effects of small molecules on the expression of CFTR protein, we used Western blotting (Farinha et al., 2002). We lysed cells, loaded SDS‐polyacrylamide mini‐gels [7% (w·v−1) polyacrylamide; BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA] with 30 mg total protein (5 mg for wild‐type CFTR) and separated protein electrophoretically. After transfer of proteins to Immobilon‐P PVDF membranes (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), we probed membranes with the mouse anti‐CFTR monoclonal antibody 596, which recognizes nucleotide‐binding domain 2 (NBD2; residues 1204–1211) (Cui et al., 2007) diluted at 1:1000 using a secondary anti‐mouse peroxidase‐labelled monoclonal antibody at 1:3000 (cat. no. 170‐6516; BioRad). Western blots were developed using the Clarity Western ECL detection system (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Ussing chamber studies of recombinant CFTR to determine CFFT‐004 concentration–response relationships

We recorded F508del‐CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− currents in FRT epithelia using a large Cl− concentration gradient to magnify current size without permeabilizing the basolateral membrane (Kalid et al., 2010). FRT epithelia were mounted in Ussing chambers (model P2300; Physiologic Instruments Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The solution bathing the basolateral membrane contained (mM): 137 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The solution bathing the apical membrane was identical to that of the basolateral solution with the exception that Cl− was replaced by gluconate to create a transepithelial Cl− concentration gradient (basolateral [Cl−], 144.6 mM; apical [Cl−], 9.6 mM). All solutions were maintained at 37°C and bubbled continuously with air under low pressure to drive buffer circulation for improved compound mixing.

To record short‐circuit current (Isc), we used a Physiologic Instruments VCC MC8 multichannel voltage/current clamp. After cancelling voltage offsets, transepithelial voltage was clamped at 0 mV and Isc recorded every 20 s at 37°C with transepithelial resistance monitored in parallel using ±5 mV voltage steps of 620 ms duration. After recording baseline Isc for ~10 min, we added the cAMP agonist forskolin (10 μM), the CFTR potentiator genistein (20 μM) and the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh‐172 (20 μM) sequentially and cumulatively at 10–20 min intervals. All compounds were added as 500× or 1000× stock solutions to 5 mL physiological salt solutions bathing the apical and basolateral membranes. For acute additions of CFFT‐004, 1000× stock solutions in DMSO were added to the apical solution only. The resistance of the filter and solutions, in the absence of cells, was subtracted from all measurements. Under the experimental conditions that we used, flow of current from the basolateral to the apical solution corresponds to Cl− movement through open CFTR Cl− channels and is shown as an upward deflection.

We consider the CFTRinh‐172‐sensitive Isc after the addition of forskolin and genistein to be a valid measure of F508del‐CFTR correction, using the relationship:

| (1) |

where I CFTR is the CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− current, N is the total number of CFTR Cl− channels in the apical membrane, i is the current flowing through a single open CFTR Cl− channel and Po is its open probability. For the CFTRinh‐172‐sensitive current to be a valid measure of F508del‐CFTR correction, it is necessary to assume that after the addition of forskolin and genistein in the above protocol, F508del‐CFTR Cl− channels possess the same Po regardless of the small molecule used for correction. In this case, I CFTR is then directly proportional to the total number of F508del‐CFTR Cl− channels in the apical membrane (N). Although we have no proof for this assumption, we consistently find that the increase in Isc achieved with genistein (20 μM) varies depending upon how much CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− current is stimulated prior to genistein addition. In contrast to measurements at 37°C (Figure 1), forskolin‐stimulated CFTR Cl− currents recorded at 27°C reach a steady plateau. Under these experimental conditions, the genistein response varies from ~40% of the total CFTRinh‐172‐sensitive Isc using a pure CFTR corrector (e.g. corr‐4a; Pedemonte et al., 2005) to virtually nothing or even a negative response using a pure CFTR potentiator or a dual‐acting small molecule, prior to genistein addition.

To determine half‐maximal concentrations (EC50 values) for CFFT‐004 correction, potentiation and dual‐action (correction‐potentiation), we constructed CFFT‐004 concentration–response relationships using Isc measurements acquired from F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia. The EC50 values for correction and dual‐action were determined 24 h post compound treatment from the CFTRinh‐172‐sensitive and peak forskolin ΔIsc values, respectively. Concentration–response data were fitted using the following formula:

| (2) |

where A and B represent the fit parameters at zero and saturating concentrations of compound (cmpd) with the Hill coefficient (H) set to 1.

To obtain EC50 values for CFFT‐004 potentiation, we used Equation (2) (Hill coefficient set to 1) to fit the maximum Isc responses elicited by additions of increasing concentrations of CFFT‐004 to the solution bathing the apical membrane of F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia. To account for differing amounts of forskolin‐stimulated CFTR Cl− current between F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia and the deactivation of CFTR‐mediated Cl− currents prior to CFFT‐004 addition, we determined slope and ΔIsc values for each Isc recording at the time of CFFT‐004 addition and normalized the slope‐corrected, maximal CFFT‐004 response to ΔIsc values obtained prior to compound addition.

Ussing chamber studies to evaluate the plasma membrane stability of recombinant CFTR

Ussing chamber studies to evaluate the effects of small molecules on the plasma membrane stability of F508del‐CFTR were performed as described by Hughes et al. (2008) and Meng et al. (2017). Following 24 h correction with either CFFT‐004 or C18, F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia were treated with cycloheximide (50 μg·mL−1) 15 min prior to t = 0 h. At t = 0, 2, 4 and 6 h after cycloheximide treatment, FRT epithelia were mounted in Ussing chambers and the Isc responses to forskolin, ivacaftor and CFTRinh‐172 recorded.

CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− currents were recorded using a large Cl− concentration gradient without permeabilizing the basolateral membrane. The solution bathing the basolateral membrane contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.36 K2HPO4, 0.44 KH2PO4, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 4.2 NaHCO3, adjusted to pH 7.2 with Tris ([Cl−], 149 mM). The solution bathing the apical membrane was identical to that of the basolateral solution with the exception that (mM) 133.3 Na gluconate +2.5 NaCl and 5 K gluconate replaced 140 NaCl and 5 KCl, respectively ([Cl−], 14.8 mM). For the purpose of illustration, unless otherwise indicated, in stability experiments Isc time courses are displayed as ΔIsc with the Isc value immediately preceding forskolin addition designated as 0 μA·cm−2; file sizes were compressed by 100‐fold data reduction. To determine transepithelial resistance (Rt), brief voltage pulses (amplitude 10 mV; frequency 0.1 Hz) were applied to epithelia to generate brief current deflections; Rt was then calculated using Ohm's law.

Short‐circuit and equivalent current studies of CF human bronchial epithelia

After two passages in BEGM™ Bronchial Epithelial Cell Growth Media (cat. no. CC‐3170, Lonza, USA), P3 hBE cells homozygous for F508del‐CFTR were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells·cm−2 (170 000 cells per filter) on HTS Transwell 24‐well filter inserts (cat no. 3378, Corning). Cells were differentiated at an ALI as described by Neuberger et al. (2011) with the basolateral media changed every other day. After 4–5 weeks of ALI culture, hBE cells typically formed electrically tight epithelia with an Rt of 200–600 Ω cm2 and were then used for equivalent current (Ieq) studies.

For F508del‐CFTR potentiation studies, Ussing chamber recordings were performed on lumacaftor‐rescued epithelia of differentiated hBE cells as described above for FRT epithelia. For F508del‐CFTR correction studies, epithelia of differentiated hBE cells were treated from the basolateral side with either control (vehicle) or test compound and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, the media bathing the basolateral membrane were removed and replaced with fresh HEPES‐buffered (pH 7.4), compound‐ and bicarbonate‐free F‐12 culture media (assay buffer). Epithelia of differentiated hBE cells were immediately mounted onto the assay platform and equilibrated to ~37°C for 30 min. Transepithelial voltage (Vt) and Rt were monitored at ~6 min intervals using a 24‐channel transepithelial current clamp amplifier (TECC‐24, EP Design, Bertem, Belgium). Ieq was calculated from values of Vt and Rt using Ohm's law after correcting for series resistance and voltage offsets unrelated to Vt. In the recorded Ieq, the first and second 4 data points reflect baseline currents under conditions where the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) is active (before addition of benzamil) and inhibited (after benzamil; 6 μM). Six measurements were then made to determine Ieq after the sequential acute addition of forskolin (10 μM), CFFT‐004 (10 μM) and the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh‐172 (20 μM). Small molecules were pre‐diluted to 10‐fold concentrations in HEPES‐buffered culture media and added to either the basolateral (forskolin) or apical (benzamil, forskolin, CFFT‐004 / ivacaftor, genistein and CFTRinh‐172) sides of the membrane. In Ieq studies, CFTR‐mediated changes in Ieq were used as a measure of functional CFTR surface expression or small molecule‐mediated functional rescue of mutant CFTR.

Patch‐clamp experiments

CFTR Cl− channels were recorded in excised inside‐out membrane patches using an Axopatch 200A patch‐clamp amplifier and pCLAMP software (both from Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA) (Sheppard and Robinson, 1997). The pipette (extracellular) solution contained (mM): 140 N‐methyl‐D‐glucamine (NMDG), 140 aspartic acid, 5 CaCl2, 2 MgSO4 and 10 N‐tris[Hydroxymethyl]methyl‐2‐aminoethanesulphonic acid (TES), adjusted to pH 7.3 with Tris ([Cl−], 10 mM). The bath (intracellular) solution contained (mM): 140 NMDG, 3 MgCl2, 1 CsEGTA and 10 TES, adjusted to pH 7.3 with HCl ([Cl−], 147 mM; free [Ca2+], <10−8 M) and was maintained at 37°C using a temperature‐controlled microscope stage (Brook Industries, Lake Villa, IL, USA) unless otherwise indicated.

After excision of inside‐out membrane patches, we added the catalytic subunit of PKA (75 nM) and ATP (1 mM) to the intracellular solution within 5 min of patch excision to activate CFTR Cl− channels. To minimize channel rundown, we added PKA to all intracellular solutions, maintained the ATP concentration at 1 mM and clamped voltage at −50 mV. The action of small molecules as CFTR potentiators was tested by addition to the intracellular solution in the continuous presence of ATP (1 mM) and PKA (75 nM). Because of the rundown of F508del‐ and A561E‐CFTR Cl− channels in excised membrane patches at 37°C (Wang et al., 2014), test interventions were not bracketed by control periods. Instead, specific interventions with test small molecules were compared with the pre‐intervention control period made with the same concentration of ATP and PKA, but without the test small molecule.

To investigate the effects of small molecules on the plasma membrane stability of F508del‐CFTR, we monitored the thermal stability of F508del‐CFTR in excised inside‐out membrane patches (Wang et al., 2014). Membrane patches were excised at 27°C and F508del‐CFTR Cl− channels activated by the addition of PKA and ATP to the intracellular solution. Once channels were fully activated and potentiated when using CFTR potentiators, the temperature of the intracellular solution was increased to 37°C, which took 2–3 min. To evaluate the thermal stability of F508del‐CFTR at 37°C, we calculated Po and normalized Po values in 30 s intervals over a 9 min period (Wang et al., 2014).

In this study, we used membrane patches containing ≤4 active channels [wild‐type CFTR, number of active channels (N) = 1; F508del‐CFTR, N ≤ 4; A561E‐CFTR, N ≤ 4; F508del‐G550E‐CFTR, N ≤ 4; F508del‐R1070W‐CFTR, N ≤ 2; and F508del‐G550E‐R1070W‐CFTR, N ≤ 4]. To determine channel number, we used the maximum number of simultaneous channel openings observed during the course of an experiment (Cai et al., 2006). To minimize errors, we used experimental conditions that robustly potentiate channel activity and verified that recordings were of sufficient length using the equation (Venglarik et al., 1994):

| (3) |

where Trecord is the time required to observe at least one single all‐open event; τo is the open time constant; N is the number of active channels and Po is the open probability. For example, under the experimental conditions employed τo = 27.8 ± 4.0 ms and Po = 0.073 ± 0.03 (means ± SD; n = 2) for F508del‐CFTR determined using membrane patches with only a single active channel. Using these data, 1.1 s is required to detect one F508del‐CFTR channel in a membrane patch, 7.8 s are required to detect two channels, 71 s are required to detect three channels, 734 s are required to detect four channels and 8046 s are required to detect five channels. Thus, under our experimental conditions, single‐channel recordings lasting ~15 min will determine whether a membrane patch contains four, but not five, active F508del‐CFTR Cl− channels.

Single‐channel currents were initially recorded on digital audiotape using a digital tape recorder (model DTR‐1204, Biologic Scientific Instruments; Intracel Ltd., Royston, UK) at a bandwidth of 10 kHz. On playback, records were filtered with an eight‐pole Bessel filter (model F‐900C/9L8L, Frequency Devices Inc., Ottawa, IL, USA) at a corner frequency (f c) of 500 Hz and acquired using a DigiData1320A interface (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) and pCLAMP software at a sampling rate of 5 kHz. To measure single‐channel current amplitude (i), Gaussian distributions were fit to current amplitude histograms. For Po and burst analyses, lists of open‐ and closed‐times were created using a half‐amplitude crossing criterion for event detection and dwell‐time histograms constructed as previously described (Sheppard and Robinson, 1997); transitions <1 ms were excluded from the analysis [eight‐pole Bessel filter rise time (T 10–90) ~0.73 ms at f c = 500 Hz]. Histograms were fitted with one or more component exponential functions using the maximum likelihood method. For burst analyses, we used a tc (the time that separates interburst closures from intraburst closures) determined from closed time histograms (wild‐type CFTR, tc = 14.5 ± 1.5 ms, n = 5; F508del‐CFTR, tc = 20.5 ± 0.8 ms, n = 18; F508del‐G550E‐CFTR, tc = 17.6 ± 1.2 ms, n = 4; F508del‐R1070W‐CFTR, tc = 13.4 ± 0.8 ms, n = 4; F508del‐G550E‐R1070W‐CFTR, tc = 18.8 ± 1.0 ms, n = 4) (Cai et al., 2006). The mean interburst interval (TIBI) was calculated using the equation (Cai et al., 2006):

| (4) |

where Tb = [mean burst duration (MBD)] × [open probability within a burst (Po(burst))]. MBD (TMBD) and Po(burst) were determined directly from experimental data using pCLAMP software. For wild‐type CFTR and revertant mutations, only membrane patches that contained a single active channel were used for burst analysis, whereas for F508del‐CFTR, membrane patches contained no more than three active channels. We analysed only bursts of single‐channel openings with no superimposed openings that were separated from one another by a time interval ≥tc. For the purpose of illustration, single‐channel records were filtered at 500 Hz and digitized at 5 kHz before file size compression by fivefold data reduction.

Data and statistical analysis

The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and data analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015), with the exception that some group sizes were unequal due to the technical difficulties with the acquisition of single‐channel data. Data recording and analyses were randomized, but not blinded. Results are expressed as means ± SEM of n observations, except Figures 1 and 9 and Supporting Information Figure S5, where data are means ± SD. To test for differences between two groups of data acquired within the same experiment, we used Student's paired t‐test. To test for differences between multiple groups of data, we used an ANOVA followed by post hoc tests. All tests were performed using SigmaPlot™ (version 13.0; Systat software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. Data subject to statistical analysis had n values ≥5 per group. In Western blotting experiments (Figure 2), n represents the number of Western blots; in Ussing chamber and Ieq studies (Figures 1, 5 and 9 and Supporting Information Figures S2 and S4), n represents the number of polarized epithelia, and in patch‐clamp experiments (Figures 3, 4 and 6, 7, 8 and Supporting Information Figures S1, S3 and S5), n represents the number of individual membrane patches obtained from different cells. To avoid pseudo‐replication, all experiments were repeated at different times.

Figure 9.

CFFT‐004 rescues F508del‐CFTR function in primary cultures of hBE cells. (A) Equivalent current (Ieq) recordings from hBE cells homozygous for the F508del‐CFTR mutation acquired at 37°C to test the action of CFFT‐004 as a corrector and dual‐acting small molecule are shown. Prior to commencing the recordings, hBE cells were treated for 24 h at 37°C with the vehicle DMSO (0.1% v·v−1), CFFT‐004 (10 μM) or lumacaftor (VX‐809; 3 μM). During the indicated periods, benzamil (Bzm; 6 μM) and CFFT‐004 (CF4; 10 μM) were added to the solution bathing the apical membrane, whereas forskolin (Fsk; 10 μM) and CFTRinh‐172 (I172; 20 μM) were added to the solutions bathing both the apical and basolateral membranes. Data are means ± SD (n = 4). (B) Isc recordings from hBE cells homozygous for the F508del‐CFTR mutation acquired at 37°C to test the action of CFFT‐004 as a potentiator are shown. Prior to commencing the recordings, hBE cells were treated with lumacaftor (3 μM) for 24 h at 37°C. During the indicated periods, benzamil (Bzm; 6 μM) and CFFT‐004 (10 μM), ivacaftor (1 μM) or the vehicle DMSO (0.1% v·v−1) were added to the solution bathing the apical membrane (Cmpd), whereas forskolin (Fsk; 10 μM), genistein (Gen; 20 μM) and CFTRinh‐172 (I172; 20 μM) were added to the solutions bathing both the apical and basolateral membranes. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Other details as in Figure 1.

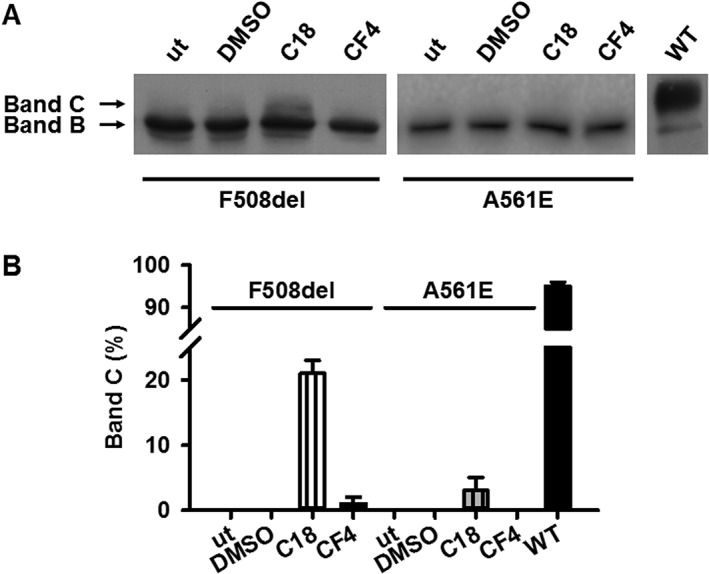

Figure 2.

Differential effects of the small molecules CFFT‐004 and C18 on the maturation of F508del‐ and A561E‐CFTR expressed in BHK cells. (A) Representative Western blots of BHK cells stably expressing F508del‐ and A561E‐CFTR are shown. CF mutant‐expressing BHK cells were treated with CFFT‐004 (5 μM), C18 (5 μM) or the vehicle DMSO (0.05% v·v−1) for 24 h at 37°C before cells were lysed and Western blotting performed; other CF mutant‐expressing BHK cells were untreated (ut). Lysates from BHK cells stably expressing wild‐type CFTR were used as a control. CFTR was detected with the mouse anti‐CFTR monoclonal antibody (596), which recognizes a region of NBD2 (1204–1211; Cui et al., 2007). Arrows indicate the positions of the band B (immature) and C (mature) forms of CFTR. (B) The amount of CFTR protein present in the mature form (band C) is expressed as a percentage of total CFTR protein [% CFTR protein processed = (band C / [bands B + C] × 100)]. Data are means ± SEM (n = 13) expressed as a percentage of that of wild‐type CFTR.

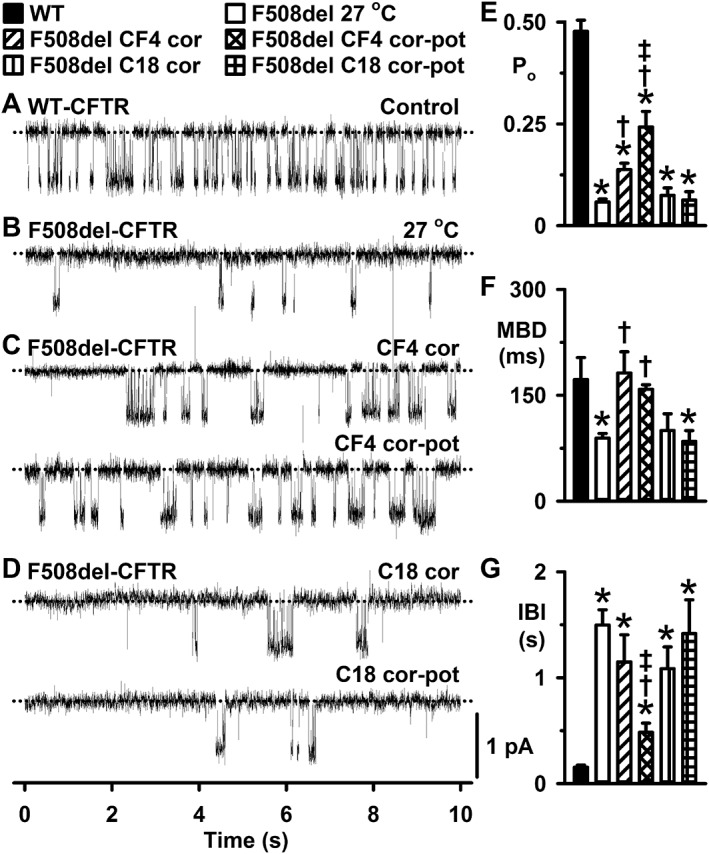

Figure 3.

CFFT‐004 corrects and potentiates F508del‐CFTR channel gating. (A–D) Representative single‐channel records of wild‐type and F508del‐CFTR in excised inside‐out membrane patches from BHK cells under the indicated experimental conditions. ATP (1 mM) and PKA (75 nM) were continuously present in the intracellular solution. When tested as correctors (cor) or dual‐acting small molecules (cor‐pot), CFFT‐004 (CF4) and C18 were used at 5 μM and either incubated with cells for 24 h at 37°C or added acutely to the intracellular solution. Prior to commencing channel recordings, cells incubated with CFFT‐004 and C18 were thoroughly washed to remove any residual small molecules from the extracellular solution; the maximum period cells were left in drug‐free solution before study did not exceed 30 min. In (C) and (D), the recordings are from the same membrane patches before and after testing CFFT‐004 and C18 as potentiators. Dotted lines indicate the closed channel state, and downward deflections correspond to channel openings. Unless otherwise indicated in this and other figures, membrane patches were voltage‐clamped at −50 mV, there was a large Cl− concentration gradient across the membrane ([Cl−]int, 147 mM; [Cl−]ext, 10 mM) and temperature was 37°C. (E–G) Po, MBD and IBI of F508del‐CFTR for the indicated conditions. Data are means ± SEM (WT, n = 5; F508del 27°C rescue, n = 18; F508del CFFT‐004 correction, n = 6; F508del CFFT‐004 dual‐action, n = 6; F508del C18 correction, n = 6; F508del C18 dual‐action, n = 6); *, P < 0.05 versus WT‐CFTR; †, P < 0.05 versus F508del‐CFTR 27 °C rescue; ‡, P < 0.05 versus CFFT‐004 correction.

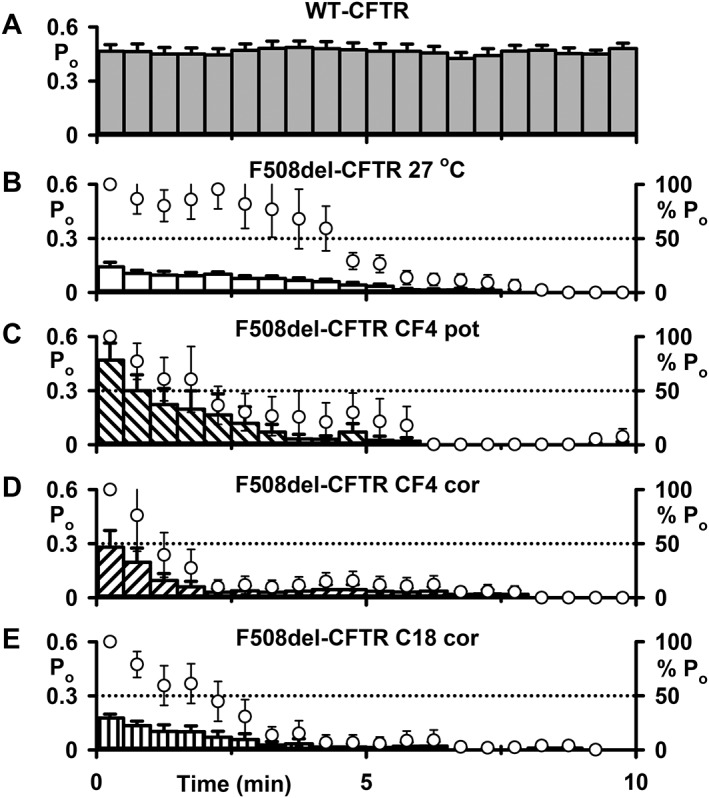

Figure 4.

Effects of CFFT‐004 on the stability defect of F508del‐CFTR in excised inside‐out membrane patches. (A–E) Time courses of Po for F508del‐CFTR in excised membrane patches commenced once channel activation was complete for the indicated experimental conditions. In (B–E), left and right ordinates show Po (bars) and normalized Po (circles), respectively. Wild‐type CFTR channels were studied at 37°C, whereas F508del‐CFTR channels were activated at 27°C before temperature was increased to 37°C and Po measured. In (C), F508del‐CFTR was rescued at 27°C before CFFT‐004 (CF4; 5 μM) was tested as a potentiator (pot) only. In (D) and (E), CFFT‐004 (5 μM; D) and C18 (5 μM; E) were tested as correctors (cor) by incubation with cells for 24 h at 37°C. In (D) and (E), prior to commencing channel recordings, cells incubated with CFFT‐004 and C18 were thoroughly washed to remove any residual small molecules from the extracellular solution. Data are means ± SEM (WT, n = 7; F508del 27°C rescue, n = 10; F508del CFFT‐004 potentiation, n = 6; F508del CFFT‐004 correction, n = 6; F508del C18 correction, n = 7). In (A) and (B), some data were originally published in Wang et al. (2014) (A, n = 4; B, n = 5); other data are newly acquired. Other details as in Figure 3.

Figure 6.

Revertant mutations modify F508del‐CFTR channel gating. (A) Representative single‐channel recordings of the indicated CFTR constructs in excised inside‐out membrane patches from BHK cells. ATP (1 mM) and PKA (75 nM) were continuously present in the intracellular solution. Dotted lines indicate the closed channel state and downward deflections correspond to channel openings. (B–D) Po, MBD and IBI for the indicated CFTR constructs. Data are means ± SEM (WT, n = 5; F508del, n = 18; F508del‐G550E, Po, n = 7, MBD and IBI, n = 4; F508del‐R1070W, Po, n = 5, MBD and IBI, n = 4; F508del‐G550E‐R1070W, Po, n = 6, MBD and IBI, n = 4); *, P < 0.05 versus WT‐CFTR; †, P < 0.05 versus F508del‐CFTR. In (B–D), the wild‐type and F508del‐CFTR data are the same as Figure 3. Other details as in Figure 3.

Figure 7.

Revertant mutations modify the action of CFFT‐004 on F508del‐CFTR. (A–C) Representative single‐channel recordings of the indicated CFTR constructs in excised inside‐out membrane patches from BHK cells treated with CFFT‐004 as a corrector or a dual‐acting small molecule in the same membrane patch. ATP (1 mM) and PKA (75 nM) were continuously present in the intracellular solution. Dotted lines indicate the closed channel state, and downward deflections correspond to channel openings. Note the change in scale bars between (A, B) and (C). For CFFT‐004 correction (CF4 cor), BHK cells were incubated with CFFT‐004 (5 μM) for 24 h at 37°C. Prior to commencing channel recordings, cells were thoroughly washed to remove any residual CFFT‐004 from the extracellular solution; the maximum period cells were left in drug‐free solution before the study did not exceed 30 min. For CFFT‐004 dual‐action (cor‐pot), after recording CFFT‐004 rescued F508del‐CFTR channel activity, CFFT‐004 (5 μM) was added to the intracellular solution in the continuous presence of ATP (1 mM) and PKA (75 nM) to test its action as a CFTR potentiator. (D–F) Po data for F508del‐G550E, F508del‐R1070W and F508del‐G550E‐R1070W (F508del‐GE‐RW) using the indicated experimental conditions (CFFT‐004 correction, CF4 cor; CFFT‐004 potentiation, CF4 pot; CFFT‐004 dual‐action, CF4 cor‐pot); only the key for F508del‐G550E is shown. Data are means ± SEM (WT, n = 5; F508del 27°C rescue, n = 18; F508del‐G550E, control and CF4 pot, n = 7; CF4 cor and CF4 cor‐pot, n = 5; F508del‐R1070W, control and CF4 pot, n = 5; CF4 cor and CF4 cor‐pot, n = 4; F508del‐G550E‐R1070W, control and CF4 pot, n = 6, CF4 cor and CF4 cor‐pot, n = 5); *, P < 0.05 versus WT‐CFTR; †, P < 0.05 versus F508del‐CFTR. In (D–F), the wild‐type, F508del‐CFTR and F508del‐CFTR revertant control data are the same as Figures 3 and 6. Other details as in Figure 3.

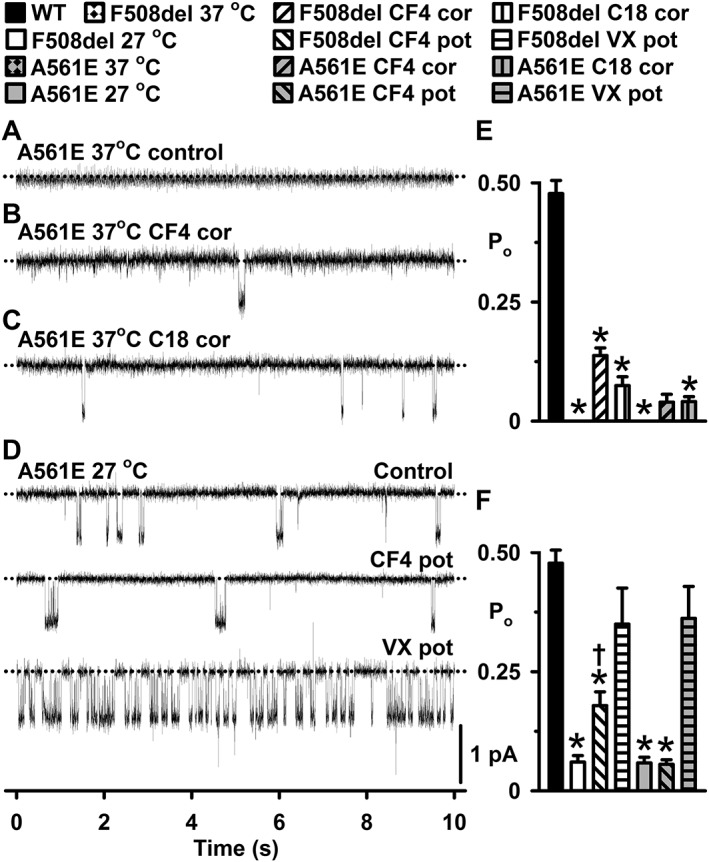

Figure 8.

CFFT‐004 fails to rescue the CF mutant A561E‐CFTR. (A–D) Representative single‐channel records of A561E‐CFTR in excised inside‐out membrane patches from BHK cells under the indicated experimental conditions. In (A), cells were incubated at 37°C, but not treated with small molecules, whereas in (B) and (C), CFFT‐004 (5 μM) and C18 (5 μM) were tested as correctors (cor) by incubation with cells for 24 h at 37°C. Prior to commencing channel recordings, cells incubated with CFFT‐004 and C18 were thoroughly washed to remove any residual small molecules from the extracellular solution. In (D), A561E‐CFTR was rescued at 27°C before CFFT‐004 (CF4; 5 μM) and ivacaftor [VX‐770 (VX); 1 μM] were tested as potentiators (pot) in different membrane patches. ATP (1 mM) and PKA (75 nM) were continuously present in the intracellular solution. Dotted lines indicate the closed channel state and downward deflections correspond to channel openings. (E and F) Po data for indicated CFTR constructs and experimental conditions; (E) CFTR correction and (F) CFTR potentiation. Data are means ± SEM (WT, n = 5; F508del 37°C control, n = 15; F508del CFFT‐004 correction, n = 6; F508del C18 correction, n = 6; A561E 37°C control, n = 15; A561E CFFT‐004 correction, n = 3; A561E C18 correction, n = 9; F508del 27°C control, n = 5; F508del CFFT‐004 potentiation, n = 5; F508del VX‐770 potentiation, n = 3; A561E 27°C control, n = 5; A561E CFFT‐004 potentiation, n = 5; A561E VX‐770 potentiation, n = 3); *, P < 0.05 versus WT‐CFTR; †, P < 0.05 versus F508del or A561E 27°C control. In (E) and (F), the wild‐type and F508del‐CFTR data are the same as Figure 3. Other details as in Figure 3.

Materials

The dual‐acting small molecule CFFT‐004 and the CFTR corrector C18 were generous gifts of EPIX Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics (CFFT) (Bethesda, MD, USA) and RJ Bridges (Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, Chicago) and CFFT, respectively, whereas the CFTR corrector lumacaftor (VX‐809) and the CFTR potentiator ivacaftor (VX‐770) were acquired from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA). PKA purified from bovine heart was purchased from Calbiochem (Merck Chemicals Ltd., Nottingham, UK). All other chemicals were of reagent grade and supplied by the Sigma‐Aldrich Company Ltd. (Gillingham, UK).

ATP was dissolved in intracellular solution, forskolin and genistein in ethanol, while all other reagents were dissolved in DMSO. Stock solutions were stored at −20°C except for that of ATP, which was prepared freshly before each experiment. Immediately before use, stock solutions were diluted to final concentration and, where necessary, the pH of the intracellular solution was readjusted to pH 7.3 to avoid pH‐dependent changes in CFTR function (Chen et al., 2009). Precautions against light‐sensitive reactions were observed when using CFTR modulators. DMSO was without effect on CFTR activity (Sheppard and Robinson, 1997). On completion of experiments, the recording chamber was thoroughly cleaned before re‐use (Wang et al., 2014).

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al., 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18 (Alexander et al., 2017a,b).

Results

CFFT‐004 is a dual‐acting CFTR modulator with independent CFTR corrector and CFTR potentiator activities

In this study, we investigated the impact of the dual‐acting small molecule CFFT‐004 (Chiang and Ghosh, 2010) on F508del‐CFTR using BHK cells expressing recombinant CFTR and primary cultures of hBE cells expressing native CFTR. By Western blotting, we explored the effects of CFFT‐004 on CFTR processing and with single‐channel recording and the Ussing chamber technique, we analysed its action on channel gating and plasma membrane stability.

The original evidence that CFFT‐004 and related compounds (e.g. CFFT‐001; Hudson et al., 2012) are dual‐acting small molecules was obtained from Ussing chamber studies of F508del‐CFTR expressing FRT epithelia. Figure 1A shows Isc recordings acquired at 37°C from FRT epithelia incubated for 24 h at 37°C with either the vehicle (DMSO 0.1% v·v−1), lumacaftor (3 μM) or CFFT‐004 [0.1–30 μM (its limit of solubility)] to investigate the action of CFFT‐004 as a CFTR corrector and as a dual‐acting small molecule. Addition of forskolin (10 μM) to vehicle‐incubated FRT epithelia elicited basal CFTR‐mediated Cl− currents, which were weakly increased by the CFTR potentiator genistein (20 μM) and inhibited by the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh‐172 (20 μM) (Figure 1A). Addition of forskolin (10 μM) to lumacaftor‐treated F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia elicited substantial CFTR‐mediated Cl− current (Figure 1A). Following decay of the transient (probably caused by a change in the electrochemical gradient across FRT epithelia following CFTR activation), acute addition of genistein (20 μM) produced a large sustained increase in CFTR‐mediated Cl− current followed by a progressive decline (Figure 1A), representing both the plasma membrane instability of F508del‐CFTR at 37°C (e.g. Wang et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Meng et al., 2017) and the inhibitory effects of genistein on fully activated CFTR Cl− channels (Lansdell et al., 2000). All CFTR‐mediated Cl− current rescued by lumacaftor was fully inhibited by CFTRinh‐172 (20 μM) (Figure 1A, C).

For F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia treated with CFFT‐004 (0.1–3 μM), the magnitude of the forskolin‐stimulated transient was smaller than that observed when F508del‐CFTR was rescued with lumacaftor (3 μM) and the response to acute addition of genistein (20 μM) was modest at best (Figure 1A). By contrast, when F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia were treated with CFFT‐004 (10 and 30 μM), the magnitude of the forskolin‐stimulated transient was similar to or greater than that observed in lumacaftor‐rescued F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia and acute addition of genistein (20 μM) only inhibited CFTR Cl− current (Figure 1A). Figure 1B shows concentration–response relationships for F508del‐CFTR rescue by CFFT‐004 derived from the data in Figure 1A and those from a second experiment (data not shown). Assuming that CFFT‐004 interacts with a single site on F508del‐CFTR (i.e. the Hill coefficient (H) = 1), the drug concentration required for half‐maximal correction of F508del‐CFTR is 11.8 ± 2.2 μM (n = 4), while that required for half‐maximal correction‐potentiation is 8.3 ± 1.2 μM (n = 4).

Figure 1C shows Isc recordings acquired at 37°C from lumacaftor‐rescued F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia acutely treated with CFFT‐004 (0.03–30 μM) to investigate its action as a CFTR potentiator. CFFT‐004 (0.03–0.3 μM) was without effect on CFTR‐mediated Cl− current, whereas subsequent acute addition of genistein (20 μM) initially increased CFTR‐mediated Cl− current, but this was promptly followed by a progressive decline of current (Figure 1C). By contrast, CFFT‐004 (1–30 μM) generated progressively larger enhancements of CFTR‐mediated Cl− current after which potentiation by genistein (20 μM) became increasingly weaker and current inhibition became the drug's predominant effect (Figure 1C). Figure 1D shows the concentration–response relationship for F508del‐CFTR potentiation by CFFT‐004 derived from the data in Figure 1C and those from a second experiment (data not shown). Assuming that CFFT‐004 interacts with a single site on F508del‐CFTR, the drug concentration required for half‐maximal potentiation is 1.6 ± 0.2 μM (n = 4). Thus, the data suggest that comparable concentrations of CFFT‐004 are required for it to correct, potentiate and act as a dual‐acting small molecule for F508del‐CFTR.

Differential effects of CFFT‐004 on F508del‐CFTR protein processing, stability and channel gating

To investigate how CFFT‐004 acts as a dual‐acting small‐molecule, we studied its effects on F508del‐CFTR heterologously expressed in BHK cells. Figure 2 demonstrates that wild‐type CFTR generated band C, the mature, fully glycosylated form of CFTR protein, whereas F508del‐CFTR produced none. Incubation of F508del‐CFTR expressing BHK cells with CFFT‐004 (5 μM) for 24 h at 37°C generated little mature CFTR protein (1% wild‐type CFTR), whereas incubation with the CFTR corrector C18 (5 μM), an analogue of lumacaftor (Eckford et al., 2014), for 24 h at 37°C produced 21% wild‐type CFTR (Figure 2). Thus, CFFT‐004, at best, modestly improves F508del‐CFTR processing in recombinant BHK cells.

To investigate the single‐channel behaviour of F508del‐CFTR rescued by CFFT‐004, we studied excised inside‐out membrane patches from F508del‐CFTR expressing BHK cells incubated at 27°C for 24–72 h or treated with CFFT‐004 (5 μM) for 24 h at 37°C. All single‐channel recordings were acquired at 37°C. Consistent with previous results (for review, see Cai et al., 2011), Figure 3 and Supporting Information Figure S1 demonstrate that the F508del mutation is without effect on current flow through open CFTR Cl− channels, but perturbs channel gating. The gating pattern of wild‐type CFTR is characterized by bursts of channel openings interrupted by brief, flickery closures, separated by longer closures between bursts (Figure 3A and Supporting Information Figure S1A). Figure 3B, F, G and Supporting Information Figure S1B, D, E reveal that the F508del mutation decreases greatly the frequency of bursts of channel openings and concomitantly shortens their duration. When tested as a CFTR potentiator by acute addition to the intracellular solution bathing excised membrane patches, CFFT‐004 (5 μM) enhanced both wild‐type and F508del‐CFTR channel gating (Supporting Information Figure S1). CFFT‐004 (5 μM) increased the frequency [by reducing interburst interval (IBI) 50%] and duration (by prolonging MBD 85%) of F508del‐CFTR channel openings to enhance Po twofold (Supporting Information Figure S1). However, CFFT‐004 did not restore the Po of F508del‐CFTR to wild‐type levels unlike ivacaftor (e.g. Wang et al., 2014) (Figure 8F and Supporting Information Figure S1C).

When tested as a CFTR corrector, CFFT‐004 (5 μM) enhanced the Po of F508del‐CFTR 1.4‐fold compared to low temperature rescue, albeit Po was still only one third that of wild‐type CFTR (Figure 3). Correction with CFFT‐004 (5 μM) increased F508del‐CFTR Po by reducing IBI 23% and increasing MBD 100% (Figure 3E–G). Of note, subsequent acute addition of CFFT‐004 (5 μM) to the intracellular solution, to explore its action as a CFTR corrector‐potentiator, led to a further enhancement of Po (1.8‐fold vs. correction alone) as a result of an additional 58% reduction in IBI (Figure 3E–G). Thus, when tested as a CFTR corrector‐potentiator, CFFT‐004 (5 μM) increased the Po of F508del‐CFTR 3.2‐fold compared to low temperature rescue to achieve a level of channel activity 51% that of wild‐type CFTR.

In contrast to the action of CFFT‐004, correction with C18 (5 μM) for 24 h at 37°C did not enhance the Po of F508del‐CFTR compared with that of low temperature rescue (P = 0.16) (Figure 3). Moreover, acute addition of C18 (5 μM) to the intracellular solution after C18‐induced correction was without effect on F508del‐CFTR channel gating (Figure 3). Thus, CFFT‐004, but not C18, acts as a dual‐acting small‐molecule, modifying F508del‐CFTR channel gating when tested as either a CFTR corrector or a CFTR potentiator. In both cases, although IBI values remained greatly prolonged, CFFT‐004 restored the MBD values to wild‐type levels (Figure 3 and Supporting Information Figure S1).

One facet of the F508del‐CFTR instability defect is channel rundown (deactivation) at 37°C in the presence of PKA and ATP (e.g. Wang et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Meng et al., 2017). To investigate whether CFFT‐004 rescues F508del‐CFTR instability, we monitored the duration of channel activity in excised membrane patches at 37°C by measuring Po once channels were fully activated by PKA‐dependent phosphorylation. Wild‐type CFTR exhibited robust, sustained channel activity characterized by Po values of ~0.5 (Figure 4). By contrast, the greatly reduced channel activity of F508del‐CFTR was unstable, declining from Po values of ~0.15 to zero within 8 min (Figure 4B). Figure 4C, D demonstrates that potentiation or correction of F508del‐CFTR with CFFT‐004 (5 μM) elevated the initial Po of F508del‐CFTR without improving the mutant protein's stability in excised membrane patches. Similarly, correction with C18 (5 μM) failed to improve F508del‐CFTR stability in excised membrane patches (Figure 4E).

To investigate further the action of CFFT‐004 on the plasma membrane instability of F508del‐CFTR, we studied CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− currents in FRT epithelia expressing F508del‐CFTR. We analysed the stability of F508del‐CFTR Cl− currents after rescuing the apical membrane expression of F508del‐CFTR by treating FRT epithelia with either CFFT‐004 (10 μM) or C18 (5 μM) for 24 h at 37°C. Because of the modest amount of mature CFTR protein rescued by CFFT‐004 (Figure 2), we did not attempt to evaluate biochemically the plasma membrane stability of F508del‐CFTR rescued by the small molecule and we increased the concentration of drug used in these functional studies. To specifically investigate the bulk population of CFTR Cl− channels present at the plasma membrane, we treated FRT epithelia with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (50 μg·mL−1) 15 min prior to mounting FRT epithelia in Ussing chambers and recording CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− currents at t = 0 h. The remaining FRT epithelia were incubated with cycloheximide (50 μg·mL−1) for 2, 4 or 6 h prior to use. After 6 h incubation, cycloheximide decreased Rt 1.8‐fold in CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia, whereas after the same period, it increased Rt 2.1‐fold in C18‐rescued F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia (Figure 5B). These data suggest that cycloheximide treatment did not impair epithelial integrity over the period of study.

Figure 5A and Supporting Information Figure S2A–D show representative recordings of CFTR‐mediated Cl− currents in F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia after rescue by C18 or CFFT‐004 at different time intervals after cycloheximide treatment. For C18‐rescued F508del‐CFTR, at t = 0 h, forskolin (10 μM) stimulated small CFTR Cl− currents, which were potentiated sevenfold by ivacaftor (1 μM) (Figure 5A). By contrast, for CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR, at t = 0 h, forskolin (10 μM) stimulated large CFTR Cl− current (4.7‐fold greater than those in C18‐rescued F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia), which were only modestly increased by ivacaftor (1 μM) (Figure 5A). Using the approach of Pedemonte et al. (2011), we quantified the different responses of C18‐ and CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR to forskolin and ivacaftor (Figure 5C). For CFFT‐004, the forskolin‐stimulated Cl− current represented ~90% of the total CFTR‐mediated Cl− current at all time points tested, whereas for C18, it was only ~25%. The agreement of these results with those of Pedemonte et al. (2011) provides further evidence that CFFT‐004 is a dual‐acting small molecule that corrects and potentiates F508del‐CFTR. The data also provide an additional explanation for the modest effects of genistein after F508del‐CFTR rescue by CFFT‐004 (Figure 1).

Figure 5D, E show the magnitude of forskolin‐stimulated and total CFTR‐mediated Cl− current at different times after FRT epithelia were treated with cycloheximide (50 μg·mL−1). For C18‐rescued F508del‐CFTR, the magnitude of forskolin‐stimulated CFTR Cl− current was constant over the 6 h period (Figure 5D). By contrast, for CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR, the magnitude of forskolin‐stimulated CFTR Cl− current was enhanced greatly at t = 0 h (3.5‐fold larger than that in C18‐rescued F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia), but declined progressively over the 6 h period to a level similar to that of the forskolin‐stimulated CFTR Cl− current of C18‐rescued F508del‐CFTR (Figure 5D). For both CFFT‐004‐ and C18‐rescued F508del‐CFTR, the total CFTR‐mediated Cl− current declined with a similar time course over the 6 h period (Figure 5E), which was comparable to that observed with CFTR Cl− currents acutely potentiated by ivacaftor in F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia rescued by lumacaftor (Meng et al., 2017). We interpret these data to suggest that CFFT‐004 does not rescue the stability defect of F508del‐CFTR in intact cells.

We previously observed a CFTR‐dependent enhanced basal Isc in Ussing chamber recordings of CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia chronically treated with ivacaftor (Meng et al., 2017). We were therefore interested to learn whether CFFT‐004 influences the magnitude of basal Isc in Ussing chamber studies. Figure 5F demonstrates noticeable basal Isc at all time points after cycloheximide treatment in CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia, but for those rescued by C18, only at t = 0 and 2 h. Of note, the magnitude of basal Isc observed with CFFT‐004 exceeded that which we observed previously for F508del‐CFTR treated chronically with ivacaftor (Figure 5F; Meng et al., 2017). Like the basal Isc observed after chronic ivacaftor treatment (Meng et al., 2017), that recorded in F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia pretreated with CFFT‐004 was CFTRinh‐172‐sensitive (Figure 5G and Supporting Information Figure S2), indicating that it is CFTR‐dependent. In conclusion, CFFT‐004 has diverse effects as a dual‐acting small molecule. It strongly potentiates F508del‐CFTR channel gating, modestly affects F508del‐CFTR protein processing, but is without effect on its plasma membrane stability defect.

Use of revertant mutations to explore the mechanism of action of CFFT‐004

Previous work investigated the rescue of F508del‐CFTR by revertant mutations, which repair defects in NBD1 and the NBD‐membrane‐spanning domain (MSD) interface to restore its plasma membrane expression, stability and function (Roxo‐Rosa et al., 2006; Mendoza et al., 2012; Rabeh et al., 2012; Farinha et al., 2013a). To understand better how CFFT‐004 rescues F508del‐CFTR, we studied the revertant mutations G550E, R1070W and G550E‐R1070W (deCarvalho et al., 2002; Thibodeau et al., 2010). Farinha et al. (2013a) demonstrated that in BHK cells, the combination revertant G550E‐R1070W restored F508del‐CFTR maturation to ~80% that of wild‐type CFTR. Figure 6 shows the effects of the G550E, R1070W and G550E‐R1070W mutations on F508del‐CFTR channel gating, and Supporting Information Figure S3 shows their effects on F508del‐CFTR stability in BHK cells. Consistent with previous results (Roxo‐Rosa et al., 2006), G550E enhanced greatly both the frequency and duration of F508del‐CFTR channel openings with the result that its Po was 1.3‐fold higher than that of wild‐type CFTR (Figure 6). By contrast, R1070W conferred on F508del‐CFTR the gating behaviour of wild‐type CFTR; values of Po, MBD and IBI of F508del‐R1070W‐CFTR did not differ significantly from those of wild‐type CFTR (P ≥ 0.45) (Figure 6). However, the combination revertant G550E‐R1070W elevated F508del‐CFTR channel activity to levels that exceeded greatly those of wild‐type CFTR; the 13.5‐fold increase in Po compared with that of F508del‐CFTR was achieved by an 8.5‐fold enhancement of MBD and a 22.1‐fold reduction in IBI (Figure 6). In contrast to the different effects of revertant mutations on F508del‐CFTR channel gating, G550E, R1070W and G550E‐R1070W all stabilized F508del‐CFTR channel activity in excised inside‐out membrane patches. Supporting Information Figure S3 demonstrates that over the period of the experiment, there was no difference between the three revertant mutations, all restored wild‐type levels of stability to F508del‐CFTR at 37°C.

To investigate the mechanism of action of CFFT‐004, we tested its effects on the F508del‐CFTR revertant mutations. Figure 7A–C shows representative single‐channel recordings, and Figure 7D–F shows mean data for CFFT‐004 tested as a potentiator, a corrector and as a dual‐acting small molecule. When tested as a potentiator, either alone or after correction (i.e. as a dual‐acting small molecule), CFFT‐004 (5 μM) enhanced the Po of each of the three F508del‐CFTR revertants, albeit the increase was minimal with F508del‐G550E‐R1070W (Figure 7D–F). By contrast, when tested as a corrector, CFFT‐004 (5 μM) enhanced the Po of F508del‐R1070W, but not F508del‐G550E nor F508del‐G550E‐R1070W (Figure 7D–F). We interpret these data to suggest that correction, but not potentiation, by CFFT‐004 might involve G550 and hence NBD1.

Action of CFFT‐004 on the CF mutant A561E‐CFTR

To explore the specificity of CFFT‐004, we tested its effects on A561E, another class II‐III‐VI CF mutation (Veit et al., 2016) found in NBD1 with defects closely comparable to those of F508del‐CFTR (Mendes et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2014). Figures 2 and 8 demonstrate that when BHK cells expressing either F508del‐ or A561E‐CFTR were grown at 37°C, no mature protein was produced and no channel activity was observed. However, the two CF mutants exhibited different responses to CFFT‐004 and C18. When BHK cells expressing A561E‐CFTR were incubated with either CFFT‐004 (5 μM) or C18 (5 μM) for 24 h at 37°C, there was no improvement in A561E‐CFTR maturation or function in contrast to the effects of the small molecules on F508del‐CFTR. Figure 2 demonstrates that there was no increase in band C, the mature fully glycosylated form of CFTR protein using either small molecule. Figure 8E shows that the Po of A561E was reduced compared to that of F508del‐CFTR when treated with CFFT‐004 (5 μM) or C18 (5 μM) as a CFTR corrector. Furthermore, CFFT‐004 failed to enhance A561E‐CFTR channel gating when tested as a CFTR potentiator. The Po of low temperature‐rescued A561E‐CFTR Cl− channels was unaffected when CFFT‐004 (5 μM) was added acutely to the intracellular solution (Figure 8F). By contrast, ivacaftor (1 μM) potentiated strongly A561E‐CFTR channel gating, restoring Po to wild‐type levels like its effect on F508del‐CFTR (Wang et al., 2014) (Figure 8F). Thus, despite the similar effects of the two mutations on CFTR, at the concentrations tested, CFFT‐004 rescues F508del‐CFTR, but not A561E‐CFTR.

CFFT‐004 has dual‐activity on native F508del‐CFTR Cl− channels

The primary site of disease in CF is the respiratory airways. Therefore, we sought to determine whether CFFT‐004 has dual‐activity on native F508del‐CFTR Cl− channels using epithelia of hBE cells from CF patients homozygous for F508del‐CFTR. Figure 9 shows Ieq and Isc measurements from epithelia of F508del‐CFTR‐expressing hBE cells acquired at 37°C.

Figure 9A compares the correction of native F508del‐CFTR in hBE cells by CFFT‐004 and lumacaftor. After inhibition of ENaC with benzamil (6 μM), forskolin (10 μM) stimulated a large transient increase in Ieq in epithelia of F508del‐CFTR‐expressing hBE cells pretreated with CFFT‐004 (10 μM) for 24 h at 37°C (Figure 9A). The approximately fivefold difference in forskolin‐stimulated ΔIeq in CFFT‐004‐treated epithelia of F508del‐CFTR‐expressing hBE cells compared with DMSO‐treated epithelia is the result of both CFFT‐004‐mediated correction and potentiation of F508del‐CFTR. Like the effects of CFFT‐004 correction on FRT epithelia expressing F508del‐CFTR (Figures 1 and 5), the potentiation of the forskolin response is likely due to the slow removal of CFFT‐004 from hBE cells. By contrast, the approximately twofold difference in CFTR‐mediated Cl− current inhibited by CFTRinh‐172 (20 μM) between the CFFT‐004‐treated and vehicle‐treated epithelia of F508del‐CFTR hBE cells in Figure 9A reflects the increased number of F508del‐CFTR Cl− channels at the apical membrane of CFFT‐004‐treated hBE cells. Although the magnitude of forskolin‐stimulated CFTR‐mediated Cl− current rescued by CFFT‐004 (10 μM) was similar to that corrected with lumacaftor (3 μM), the CFFT‐004‐rescued Ieq declined progressively, whereas the lumacaftor‐rescued Ieq persisted (Figure 9A). As a result, the CFTRinh‐172‐sensitive Ieq elicited by 24 h treatment with CFFT‐004 (10 μM) compared to its vehicle (DMSO, 0.1% v·v−1) was only one quarter that of the lumacaftor‐rescued Ieq (Figure 9A). Thus, CFFT‐004 corrected native F508del‐CFTR in hBE cells with 25% of the efficacy of lumacaftor.

Figure 9B compares potentiation of lumacaftor‐rescued native F508del‐CFTR in hBE cells by CFFT‐004 and ivacaftor. After inhibition of ENaC‐mediated Isc with benzamil (6 μM) and activation of CFTR‐mediated transepithelial Cl− current with forskolin (10 μM), the effects of CFTR potentiators were tested on steady‐state CFTR Cl− currents. Ivacaftor (1 μM) elicited a large transient current, which declined to a steady‐state approximately twofold larger than that achieved by forskolin alone (Figure 9B). By contrast, CFFT‐004 (1 μM) had little or no effect, whereas CFFT‐004 (3 and 10 μM) potentiated similar amounts of CFTR‐mediated Cl− current, achieving steady‐state currents about half of those of ivacaftor (Figure 9B). Subsequent addition of genistein (20 μM) after CFFT‐004 or ivacaftor potentiated currents to a level comparable with the ivacaftor transient after which currents declined progressively before inhibition by CFTRinh‐172 (20 μM) (Figure 9B). To compare potentiator efficacy, we measured the change in current elicited by potentiators relative to that of forskolin. For ivacaftor (1 μM), ΔIsc VX‐770 / ΔIsc Fsk = 2.0, while for CFFT‐004 (3 and 10 μM), ΔIsc CFFT‐004 / ΔIsc Fsk = 1.3 and 1.2, respectively (ΔIsc DMSO / ΔIsc Fsk = 0.9). Thus, when corrected for the vehicle response (DMSO, 0.1% v·v−1), CFFT‐004 potentiated native F508del‐CFTR in hBE cells with approximately 40% of the efficacy of ivacaftor.

Finally, we investigated the effects of CFFT‐004 on native A561E‐CFTR Cl− currents using epithelia of hBE cells from CF patients homozygous for A561E‐CFTR (Supporting Information Results and Figure S4). As a control, we studied hBE cells from CF patients homozygous for F508del‐CFTR. Consistent with the data in Figure 9 and our studies of recombinant F508del‐ and A561E‐CFTR (Figures 2 and 8), CFFT‐004 rescued F508del‐CFTR, but not A561E‐CFTR in epithelia of hBE cells (Supporting Information Figures S4). We conclude that CFFT‐004 corrects and potentiates native F508del‐CFTR Cl− channels.

Discussion

This study investigated the rescue of native and recombinant F508del‐CFTR by the CFTR corrector‐potentiator CFFT‐004. CFFT‐004 partially restored channel gating to F508del‐CFTR but only modestly improved plasma membrane expression and failed to rescue its stability defect. These data argue that a single small molecule, used alone, might not be enough to rescue completely CF mutants.

Previous work identified two types of CFTR corrector‐potentiators. The first group of dual‐acting small molecules (e.g. aminoarylthiazoles; Pedemonte et al., 2011) promote the trafficking of F508del‐CFTR to the plasma membrane in the same way as typical CFTR correctors, such as the bisaminomethylbithiazole corr‐4a (Pedemonte et al., 2005). However, aminoarylthiazoles are atypical CFTR potentiators, which require protein synthesis before they augment CFTR channel activity (Pedemonte et al., 2011). Building on these studies, Eckford et al. (2014) demonstrated that the CFTR correctors lumacaftor and C18 exert post‐translational effects on F508del‐CFTR in addition to acting co‐translationally to allow F508del‐CFTR to traffic to the plasma membrane. Pretreatment with lumacaftor and C18 accelerated F508del‐CFTR activation by PKA‐dependent phosphorylation, while C18 enhanced both ATP‐dependent and independent channel activity of phosphorylated purified F508del‐CFTR protein (Eckford et al., 2014). Our observation that CFFT‐004 acutely potentiated F508del‐CFTR channel gating after rescue by either low temperature incubation or CFFT‐004 pretreatment indicates that the mechanism of action of CFFT‐004 is distinct from that of aminoarylthiazoles, lumacaftor and C18, which possess typical CFTR corrector activity, but atypical CFTR potentiator action. The enhancement of F508del‐CFTR Po achieved by pretreatment with CFFT‐004 compared to low temperature rescue argues that this small molecule interacts directly with F508del‐CFTR to partially repair the structural defects responsible for aberrant channel gating. By contrast, correction with lumacaftor did not enhance F508del‐CFTR Po compared to low temperature rescue (Kopeikin et al., 2014; Meng et al., 2017).

A second class of dual‐acting small molecules, cyanoquinolines, with independent CFTR corrector and CFTR potentiator activities, was identified by Phuan et al. (2011). One cyanoquinoline CoPo‐22 trafficked F508del‐CFTR to the plasma membrane with comparable efficacy to the CFTR corrector corr‐4a and potentiated F508del‐CFTR‐mediated apical membrane Cl− currents after low temperature rescue with efficacy similar to the CFTR potentiator genistein (Phuan et al., 2011). Although we did not directly compare the effects of CFFT‐004 and CoPo‐22, several lines of evidence suggest that CFFT‐004 is a dual‐acting small molecule with independent CFTR corrector and CFTR potentiator activities. First, CFFT‐004 corrected and potentiated F508del‐CFTR activity in both FRT epithelia and BHK cells expressing recombinant CFTR as well as epithelia of CF patient‐derived hBE cells. Second, albeit with differing efficacies, CFFT‐004 rescued F508del‐CFTR expression biochemically and functionally. Third, correction with CFFT‐004 improved F508del‐CFTR channel gating compared to low temperature‐rescued F508del‐CFTR. Fourth, single‐channel studies demonstrated that CFFT‐004 acutely potentiated F508del‐CFTR channel gating following CFFT‐004‐mediated rescue of F508del‐CFTR expression. Finally, the F508del‐CFTR revertant mutation G550E inhibited correction, but not potentiation by CFFT‐004. Taken together, the simplest interpretation of these data is that CFFT‐004 is a CFTR corrector‐potentiator capable of independently restoring the plasma membrane expression of F508del‐CFTR and potentiating its channel gating.

An important finding of this study is the differential effects of CFFT‐004 on the protein processing, plasma membrane stability and channel gating defects of F508del‐CFTR. CFFT‐004 robustly improved F508del‐CFTR channel gating in recombinant BHK cells, albeit without restoring the wild‐type pattern of channel gating. By contrast, using recombinant BHK cells, its effects on F508del‐CFTR protein processing (as measured by production of mature CFTR protein) were modest at best and it was without any effect on the plasma membrane stability of F508del‐CFTR. One possible interpretation of these results might be that CFFT‐004 promoted the traffic of immature F508del‐CFTR protein to the plasma membrane by an unconventional secretory pathway (Gee et al., 2011). However, F508del‐CFTR is only delivered to the plasma membrane by this route when the conventional secretory pathway is inhibited (Gee et al., 2011). We consider a more likely explanation for the different effects of CFFT‐004 on F508del‐CFTR expression and function to be the much higher sensitivity of single‐channel recording to detect CFTR than Western blotting. Single‐channel studies quantify current flow through open channels and the pattern of channel gating. They are not designed to provide information about CFTR expression levels. For this purpose, it is necessary to measure macroscopic CFTR Cl− currents by whole‐cell recording or the Ussing chamber technique. Indeed, by studying CFTR‐mediated Cl− currents in F508del‐CFTR expressing FRT epithelia, we found that comparable concentrations of CFFT‐004 were required for F508del‐CFTR correction and potentiation. Interestingly, similar results were previously reported for two other dual‐acting small molecules, EN277I, an efficacious aminoarylthiazole (Pedemonte et al., 2011) and CoPo‐22, the most active cyanoquinoline (Knapp et al., 2012).

Once delivered to the plasma membrane, F508del‐CFTR exhibits reduced stability because of its decreased thermostability (e.g. Wang et al., 2011) and accelerated endocytosis (e.g. Swiatecka‐Urban et al., 2005). Although F508del‐CFTR stability studies similar to our own were not performed, previous data suggest that aminoarylthiazoles and cyanoquinolines might rescue the stability defect of F508del‐CFTR (Pedemonte et al., 2011; Phuan et al., 2011; Knapp et al., 2012). Importantly, unlike some CFTR potentiators such as ivacaftor (Cholon et al., 2014; Veit et al., 2014), there was no evidence of F508del‐CFTR destabilization when dual‐acting small molecules were tested as CFTR potentiators (Phuan et al., 2011; Knapp et al., 2012). By contrast, CFFT‐004 failed to rescue the plasma membrane stability of F508del‐CFTR. Like ivacaftor (Meng et al., 2017), in cell‐free membrane patches, potentiation with CFFT‐004 accelerated F508del‐CFTR deactivation (Figure 4B, C). Moreover, in polarized epithelia F508del‐CFTR correction with CFFT‐004 elicited large forskolin‐stimulated CFTR Cl− currents which declined over time (Figure 5D, E). These data concur with the idea that the thermal instability of F508del‐CFTR is related to its channel activity (Liu et al., 2012). They also argue that unlike the action of revertant mutations (Supporting Information Figure S3), CFFT‐004 does not repair the structural defects that cause F508del‐CFTR thermoinstability.

An intriguing feature of our F508del‐CFTR stability studies was the large CFTR‐dependent basal currents observed in Ussing chamber recordings of CFFT‐004‐rescued F508del‐CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia. We previously observed elevated basal currents in CFTR‐expressing FRT epithelia treated chronically with ivacaftor (Meng et al., 2017). However, the basal currents observed with F508del‐CFTR rescued by CFFT‐004 were larger than those detected with ivacaftor (Figure 5F; Meng et al., 2017). The simplest interpretation of these currents is that they represent CFFT‐004 potentiation of F508del‐CFTR Cl− channels activated by components of the culture media used to treat cells with small molecules. A likely explanation for their absence in single‐channel studies is the use of excised cell‐free membrane patches, leading to the loss of cytosolic constituents.

Pedemonte et al. (2010) demonstrated that cell background influences F508del‐CFTR rescue by CFTR correctors, but not CFTR potentiators. For aminoarylthiazole and cyanoquinoline CFTR corrector‐potentiators, there also appears to be some effect of cell background on F508del‐CFTR rescue when they are tested as CFTR correctors (Pedemonte et al., 2011; Phuan et al., 2011). For example, the aminoarylthiazole EN277I corrected F508del‐CFTR expression in recombinant FRT and A549 cells, but not in recombinant CFBE41o− cells (Pedemonte et al., 2011). Our own data do not exclude the possibility that cell background influences the action of CFFT‐004. Nevertheless, the finding that CFFT‐004 acts as an F508del‐CFTR corrector in recombinant FRT and BHK cells and CF patient‐derived hBE cells suggests that it is likely to act directly on F508del‐CFTR.

More than 2000 mutations have been identified in the CFTR gene (http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/cftr/), but not all cause disease. Of the relatively small number that have been investigated, many affect CFTR in multiple ways (Veit et al., 2016), suggesting that efficacious CFTR corrector‐potentiators would have wide application. To begin to explore the action of CFFT‐004 on other CF mutants, we selected for study A561E‐CFTR. Like F508del, A561E causes a temperature‐sensitive folding defect in NBD1 that perturbs CFTR processing, plasma membrane stability and channel gating (Mendes et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2014). At the concentrations tested, CFFT‐004 corrected and potentiated F508del‐CFTR, but was without effect on A561E‐CFTR. One possible explanation for the data is that the processing defect caused by A561E is distinct from that of F508del and less amenable to rescue by revertant mutations (Roxo‐Rosa et al., 2006) and the CFTR correctors lumacaftor and C18 (Awatade et al., 2015; present study). Interestingly, CFFT‐004 was also without effect on murine F508del‐CFTR (see Supporting Information Results and Figure S5) in agreement with other cross‐species comparative studies of CFTR (Lansdell et al., 1998a; Ostedgaard et al., 2007; Van Goor et al., 2009). Taken together, the data highlight the challenge of identifying CFTR corrector‐potentiators that target multiple CF mutations.

While dual‐acting small molecules might act indirectly to rescue F508del‐CFTR, the simplest interpretation of the data is that these agents interact directly with F508del‐CFTR to repair folding and assembly defects and hence improve its plasma membrane expression and channel gating. Pedemonte et al. (2011) interpreted the similar effects of the aminoarylthiazole EN277I as a CFTR corrector and CFTR potentiator to suggest that it rescues F508del‐CFTR expression and function by a common mechanism. By contrast, Knapp et al. (2012) posited the idea of a single binding site for both the CFTR corrector and CFTR potentiator activities of cyanoquinolines that alters its conformation during the processing of F508del‐CFTR and its delivery to the plasma membrane. Interestingly, 4,6,4′‐trimethylangelicin, a CFTR corrector‐potentiator with anti‐inflammatory properties, exhibits independent corrector and potentiator activities similar to those of lumacaftor and ivacaftor and, like lumacaftor, interacts directly with MSD1 of CFTR (Tamanini et al., 2011; Loo et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2013; Favia et al., 2014; Laselva et al., 2016). Similarly, thymosin α1, a naturally occurring peptide, reduces inflammation, while restoring the expression and function of F508del‐CFTR (Romani et al., 2017). Because thymosin α1 is approved for clinical use as an immunomodulator (Goldstein and Goldstein, 2009), further studies comparing its action with clinically used small molecule CFTR modulators should be prioritized.

In this study, we found that potentiation by CFFT‐004 was unaffected by the F508del‐CFTR revertant mutations G550E and R1070W (deCarvalho et al., 2002; Roxo‐Rosa et al., 2006; Thibodeau et al., 2010; Farinha et al., 2013a), but correction was abolished by G550E. We interpret these data to suggest that correction by CFFT‐004 involves amino acid sequences within NBD1, possibly ATP‐binding site 2. Interestingly, using in silico structure‐based screening, Kalid et al. (2010) hypothesized the locations of three potential binding sites for small molecules on F508del‐CFTR: (i) the NBD1:NBD2 interface, (ii) the NBD1:ICL4 cavity formed by deletion of F508 and (iii) the NBD1‐MSD2 and NBD2‐MSD1 interfaces. Following functional testing, Kalid et al. (2010) identified two CFTR corrector‐potentiators: EPX‐107979, binding at the NBD1‐MSD2 and NBD2‐MSD1 interfaces; and EPX‐108380, binding at the NBD1:NBD2 interface (Kalid et al., 2010). Given the location of G550 within ATP‐binding site 2 of CFTR (Lewis et al., 2004; Gadsby et al., 2006), CFFT‐004 might bind at the same or a closely related site to that for EPX‐108380. However, NMR data revealed that the related dual‐acting small molecule CFFT‐001 interacts with β strands S3, S9 and S10 in NBD1 to promote NBD dimerization (Hudson et al., 2012). Thus, an alternative explanation of our data is that the action of the G550E revertant on F508del‐CFTR hinders access of CFFT‐004 to its binding‐site, limiting the compound's action.