Abstract

Traditional nuclear medicine ligands were designed to target cellular receptors or transporters with a binding pocket and a defined structure–activity relationship. More recently, tracers have been developed to target pathological protein aggregations, which have less well-defined structure–activity relationships. Aggregations of proteins such as tau, α-synuclein, and β-amyloid (Aβ) have been identified in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias, and Parkinson’s disease (PD). Indeed, Aβ deposition is a hallmark of AD, and detection methods have evolved from coloured dyes to modern 18F-labelled positron emission tomography (PET) tracers. Such tracers are becoming increasingly established in routine clinical practice for evaluation of Aβ neuritic plaque density in the brains of adults who are being evaluated for AD and other causes of cognitive impairment. While similar in structure, there are key differences between the available compounds in terms of dosing/dosimetry, pharmacokinetics, and interpretation of visual reads. In the future, quantification of Aβ-PET may further improve its utility. Tracers are now being developed for evaluation of tau protein, which is associated with decreased cognitive function and neurodegenerative changes in AD, and is implicated in the pathogenesis of other neurodegenerative diseases. While no compound has yet been approved for tau imaging in clinical use, it is a very active area of research. Development of tau tracers comprises in-depth characterisation of existing radiotracers, clinical validation, a better understanding of uptake patterns, test-retest/dosimetry data, and neuropathological correlations with PET. Tau imaging may allow early, more accurate diagnosis, and monitoring of disease progression, in a range of conditions. Another marker for which imaging modalities are needed is α-synuclein, which has potential for conditions including PD and dementia with Lewy bodies. Efforts to develop a suitable tracer are ongoing, but are still in their infancy. In conclusion, several PET tracers for detection of pathological protein depositions are now available for clinical use, particularly PET tracers that bind to Aβ plaques. Tau-PET tracers are currently in clinical development, and α-synuclein protein deposition tracers are at early stage of research. These tracers will continue to change our understanding of complex disease processes.

Keywords: PET, Radiotracer, Beta-amyloid, Tau, Alpha-synuclein, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

Traditionally, nuclear medicine ligands were primarily designed for targeting cellular receptors or transporters. They were tightly bound, and often internalized or transported into the cell and trapped inside by metabolic transformation, while unbound ligand was cleared. More recently, a class of imaging tracers has become available whose members bind misfolded protein aggregates. This new paradigm requires different lead optimization, different types of analysis, and quantitation. Previous approaches targeted a binding pocket where derivatives of ligands displayed a defined structure-activity relationship. Examples of protein aggregate imaging include Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein. Such investigations required the design of a molecule that binds to β-sheets. The structure–activity relationship is less well defined, as no distinct binding pockets are present. Importantly, all protein depositions show a similar structural motif, and achievement of selectivity is the most important optimization goal. Nonetheless, protein sequence and aggregate structures are different enough that highly specific imaging agents have been developed for some of these targets.

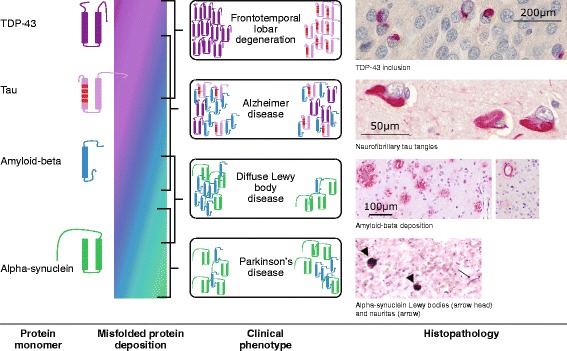

Pathological protein depositions have been identified in a range of neurodegenerative diseases (Mollenhauer & Trenkwalder 2009). Tau and 43-kDa Tar DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) are present in neurofibrillary tangles characteristic of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and AD; Aβ plaques are the hallmark of AD; and α-synuclein has been identified in the pathognomonic bodies of diffuse Lewy body disease and PD. An overview of the misfolded protein depositions discussed in this article, with their associated histopathology and clinical manifestation, is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic summary of key proteins present in frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Alzheimer’s disease, diffuse Lewy body disease and Parkinson disease. Protein monomers and their distribution for different clinical phenotypes are illustrated with symbolic drawings. Exemplary histopathology images are presented for TDP-43 inclusion, neurofibrillary tau tangles (immunohistochemistry with antibody AT8), amyloid-beta deposition (immunohistochemistry with monoclonal 6E10 Aβ antibody), and α-synuclein Lewy body inclusions (Images of TDP-43 inclusions, tau tangles, and Aβ deposits courtesy of Walter Schulz-Schaeffer, Goettingen, Germany)

Co-pathologies have also been observed, in which more than one protein forms a deposition. Identification of in vivo biomarkers for such conditions will improve diagnosis and classification of patients, provide prognostic information, and improve the efficiency of drug development. This paper will discuss some of the new positron emission tomography (PET) tracers that are being developed to target misfolded protein depositions such as Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein.

Review

Established protein tracers–detection of Aβ plaques

AD is a chronic neurodegenerative disease that can now be detected in vivo by biomarkers years before clinical manifestation. The deposition of Aβ plaques is considered one hallmark in the pathogenesis of AD, and a hypothetical model of biomarker temporal evolution has been proposed that matches the sequence of molecular events proposed in the amyloid cascade hypothesis (Jack & Holtzman 2013). The model begins with Aβ42 overproduction and aggregation, with decreased clearance, followed by plaque formation. Thus Aβ-PET and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42 levels are the first markers to become abnormal in AD pathogenesis, although these biomarkers are not approved for prediction of disease progression or therapeutic monitoring.

The earliest methods of detecting Aβ plaques post mortem used coloured dyes–Congo red and thioflavin T–that bind to the β-sheet structure of Aβ (Glenner 1980). Thioflavin T was used as the basis for the development of the first radiolabelled molecules for use in PET. To date, several molecules have been studied in humans (Kung 2012): 11C-Pittsburgh compound B, 18F-florbetapir, 18F-florbetaben, 18F-flutemetamol, and NAV4694. (Table 1) 18F-florbetapir, 18F-florbetaben, and 18F-flutemetamol have been approved in Europe and US for clinical use in PET evaluation of Aβ neuritic plaque density in the brains of adults who are being evaluated for AD and other causes of cognitive impairment. While these agents are becoming increasingly established in routine clinical practice, there are important learnings from their clinical development and considerations that should be taken into account for future research and development of protein deposition tracers. Some of the peculiarities are described briefly in the following paragraphs.

Table 1.

Overview Aß tracers

| Tracer name | Chemical structure | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Benzothiazole derivatives | ||

| [11C]-PiB (Klunk et al. 2004) |

|

• Investigational |

| [18F]-flutemetamol (VizamylTM) (GE Healthcare 2014) |

|

• Approved for clinical use |

| • Injected dose: 185 MBq | ||

| • Effective dose: 5.9 mSv (32 μSv/MBq) | ||

| • Imaging window: 90-110 min p.i. | ||

| • Scan duration: 20 min | ||

| • Visual assessment: color | ||

| Benzofuran derivative | ||

| [18F]-NAV4694 (formerly AZD4694) (Cselényi et al. 2012) |

|

• Investigational |

| Stilbene derivatives | ||

| [18F]-florbetaben (NeuraCeqTM) (Piramal Imaging 2014) |

|

• Approved for clinical use |

| • Injected dose: 300 MBq | ||

| • Effective dose: 5.8 mSv (19 μSv/MBq) | ||

| • Imaging window: 90-110 min p.i. | ||

| • Scan duration: 20 min | ||

| • Visual assessment: grey scale | ||

| [18F]-florbetapir (AmyvidTM) (Eli Lilly 2013) |

|

• Approved for clinical use |

| • Injected dose: 370 MBq | ||

| • Effective dose: 7.0 mSv (19 μSv/MBq) | ||

| • Imaging window: 30-50 min p.i. | ||

| • Scan duration: 10 min | ||

| • Visual assessment: grey scale | ||

The three approved agents have a planar chemical structure that is suitable for binding to β-sheets in Aβ plaques. All approved agents follow the same mechanism of binding, but their different chemical structures lead to differences with regard to dosing and dosimetry; pharmacokinetics, including partitioning into grey and white matter structures; and interpretation of visual reads (Eli Lilly 2013; Piramal Imaging 2014; GE Healthcare 2014). For example, 18F-florbetapir and 18F-florbetaben PET images are approved for evaluation in greyscale, while 18F-flutemetamol PET images are read using a colour scale when used in the clinical setting. Thus each tracer requires a unique medical education programme to ensure reliable assessment of scans and to distinguish uptake in white matter from cortical grey matter.

Regulatory approval for Aβ PET scan assessment is currently based solely on a binary visual read-out, and all three reading methods have been validated against histopathology (Clark et al. 2012; Curtis et al. 2015; Sabri et al. 2015a). Of note, imaging agents used in oncology such as 18F-FDG or 18F-FLT become trapped in tumours leading to a stable or even increasing signal over time (Shields et al. 1998). In Aβ imaging, however, the tracer instead shows decreasing signal or standardised uptake values (SUVs) over time, as a result of washout after binding to Aß plaque-affected cortical areas. In addition, quantification of Aβ-PET scans typically involves calculating the SUV ratio, where the reference region is a region with a ligand uptake and washout pattern similar to Aß-plaque-affected cortical areas regardless of whether Aβ plaques are present (Schmidt et al. 2015). A number of different reference regions have been proposed (Landau et al. 2015), but further discussion is outside the scope of this review. Quantification of PET scans has the ability to better detect longitudinal changes during therapeutic intervention and has the potential for automated analysis via software with more detailed regional analysis. Future uses of Aβ-PET quantification, though not approved for routine clinical use, may include improved assessment in uncertain clinical cases, drug trial enrichment by patient selection, pre-symptomatic staging of disease, and therapeutic monitoring. Such uses require robust longitudinal assessment, reliable reference-region validation, and standardisation.

Beyond AD, amyloid-PET provides a unique opportunity for in vivo research of other conditions that are present with Aβ deposition. For example, Aβ-PET may also detect other plaque types and states of amyloid (e.g. diffuse plaques) (Sabri et al. 2015b), and thus may provide additional insights into the disease and its pathogenesis. Other conditions with Aβ-plaque depositions are reported, such as Lewy body diseases, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, brain trauma, and Down syndrome. As specific as the current tracers are for Aβ over other misfolded protein aggregates, somewhat surprisingly they do bind other amyloids outside the brain. 18F-Florbetaben and 18F-florbetapir have been reported to bind amyloid deposits in cardiac amyloidosis (Dorbala et al. 2014; Catafau & Bullich 2015; Mollee et al. 2015), and these tracers are also hypothesized to bind other peripheral amyloid deposits. In addition, tracers may also have value as a myelin biomarker in conditions such as multiple sclerosis (Matías-Guiu et al. 2015), by virtue of their white-matter signal.

Protein deposition tracers under development

Detection of tau protein

Tau protein is the name given to soluble microtubule-associated protein (MAP), which is essential for regulating intracellular transport (Spillantini & Goedert 2013). Six different isoforms of tau exist, which can be distinguished by their number of binding domains (either three or four), and different forms are accumulated in different diseases (Delacourte 1999; Braak & Braak 1998). Furthermore, hyperphosphorylation and other post-translational modifications can have an impact on tau conformation, leading to, for example, aggregation in filamentous structures.

Tau protein aggregation leads to neuronal cell dysfunction and death, and studies show a strong association between tau deposits, decreased cognitive function, and neurodegenerative changes in AD. While the evolution of AD neuropathology depends on interactions between Aβ and tau (Jucker & Walker 2011), the relative contributions of the two proteins in the development of AD remain unclear. There is emerging evidence from studying hereditary Alzheimer’s Disease (e.g. DIAN study) that continues to point to a primary role of Aß in AD. Significant proportions of the observed variance in age at symptom onset can be explained by family history and mutation type (Ryman et al. 2014). Nevertheless, several other questions remain including the presence of Aβ deposition in cognitively normal individuals and time to development of first symptoms or the weak correlation between plaque load and cognition (Morris et al. 2014). Expanding the view of the AD pathogenesis beyond Aβ and tau pathology and considering aspects such as lifestyle, cognitive reserve may provide answers in the future. Imaging Aß and tau allows investigators to look at the impact on cognition and follow subjects from an earlier stage. In addition to AD several neurodegenerative diseases – including chronic traumatic encephalopathy, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, and some variants of frontotemporal lobar degeneration – have been described in which tau aggregate deposition is a dominant pathology (Mohorko & Bresjanac 2008; Lee et al. 2001; McKee et al. 2009).

Tau is a more complex target than Aβ in that the monomer protein is much larger than Aβ, is represented in different isoforms in different diseases, is present in lower amounts and has a distinct anatomic spread throughout the brain as the different diseases progress. These characteristics, and the intracellular localisation, make the requirements for a tau PET tracer more challenging (Villemagne et al. 2015).

Several tau imaging compounds have been described in preclinical and clinical studies. To date, however, none have been approved. The first 18F tracer with tau binding was 18F-FDDNP, although the compound suffered from a lack of selectivity (Kepe et al. 2013). Regional uptake patterns in the brain were therefore required to differentiate Aβ and tau. Meanwhile, more-selective tracers have become available. 11C-PBB3, allows tau imaging in AD and non-AD tauopathies such as corticobasal syndrome. However, the 11C label is not preferred, as it limits widespread use due to its short half-life (20 min) (Shimada et al. 2015). Studies with the 18F-labelled tracers THK-523 and THK-5117 showed that these compounds do not correlate with Aβ distribution, but instead follow the known distribution of tau (Harada et al. 2013). However, high retention in white matter limits their use in the clinical setting. An improved compound from the series, 18F-THK-5351, provided information on tau neurofibrillary tangle pathology in living individuals in initial studies (Harada et al. 2015). The usefulness for detection of tau pathology in pure tauopathies, however, needs to be demonstrated clinically. The Siemens (now Avid) compound 18F-T808 showed good preclinical properties as well as good pharmacokinetic characteristics in a first-in-human study, although development was hampered by strong defluorination (Chien et al. 2014). Another derivative, 18F-T807 (now AV1451), showed slower kinetics but good imaging data in AD as well as in some other tauopathies. Off-target activity in the striatum and choroid plexus is, however, described for this compound (Chien et al. 2013). In comparison with other compounds, 18F-T807 has been evaluated in the most subjects. Recently presented data on three Roche tau tracers in humans showed that 18F-RO6958948 has a promising clinical profile, with good brain uptake and little retention in cognitively normal young individuals (Wong et al. 2015). The agent also has a distribution broadly consistent with published post-mortem data, including low, homogenous uptake in controls, higher, heterogeneous uptake in AD, and a different binding pattern when compared with Aβ tracers. Notably there was no apparent brain penetration of radiolabelled metabolites and no defluorination. A clinical study is ongoing to collect test-retest and whole-body dosimetry data. Furthermore, first-in-human data of the Genentech tau tracer (18F-GTP1) were recently presented, indicating a promising clinical profile (Sanabria Bohorquez et al. 2015). Finally, 18F-PI-2014 was tested recently in humans and has shown uptake in tau-target regions consistent with tau binding (Piramal Imaging, data on file). Very recently, preclinical data from 18F-MK-6240 were published (Walji et al. 2016). This 18F-labeled agent combines good in vitro characteristics for NFT binding and clean off-target profile with suitable physicochemical properties and pharmacokinetics in rhesus monkeys. A clinical study is underway and results should be expected soon. A summary of tau tracer characteristics and key features of those with published structural information is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of published tau protein tracers updated from (Villemagne et al. 2015)

| Tracer name | Chemical structure | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Pyridinyl-butadienyl-benzothiazole derivative | ||

| [11C]-PBB3 (Maruyama et al. 2013; Hashimoto et al. 2014) |

|

• Selectively binds to tau |

| • Retention of 11C-PBB3 in the venous sinuses | ||

| • Retention of tracer in basal ganglia in patient with corticobasal degeneration suggests that it might bind to non-AD tauopathies | ||

| Dialkylamino-naphthylethylidene derivative | ||

| [18F] FDDNP (Kepe et al. 2013; Thompson et al. 2009; Small et al. 2013; Shoghi-Jadid et al. 2002; Smid et al. 2013) |

|

• First 18F-tracer with tau binding |

| • Lack of selectivity for tau; nanomolar binding affinity to Aβ | ||

| • Very limited dynamic range | ||

| • Regional brain retention used for differentiating Aβ and tau | ||

| Benzimidazole derivatives | ||

| [11C]-N-Methyl-Lansoprazole (Shao et al. 2012; Fawaz et al. 2014) |

|

• In vitro binding to paired helical filament-tau demonstrated |

| • No brain uptake in mice (P-glycoprotein substrate) | ||

| • Brain uptake in non-human primates | ||

| • No human studies reported | ||

| [18F]-N-Methyl-Lansoprazole (Fawaz et al. 2014) |

|

|

| Quinoline derivatives | ||

| [18F]-THK-523 (Harada et al. 2013) |

|

• Slow kinetics |

| • Non-specific binding (white matter, brain stem) | ||

| • No detection of non-AD tauopathies (Pick’s disease; three-repeat tauopathy) | ||

| [18F]-THK-5105 (Okamura et al. 2013; Okamura et al. 2014) |

|

• Faster kinetics and higher contrast than 18F-THK-523 |

| • Non-specific binding (white matter, brain stem) | ||

| [18F]-THK-5117 (Okamura et al. 2013; Okamura et al. 2015) |

|

|

| [18F]-THK-5351 (Harada et al. 2015) |

|

• Faster kinetics and higher contrast than THK-523 |

| • Lower white matter retention | ||

| • Higher signal-to-noise ratio compared with 18F-THK-5105 and 18F-THK-5117 | ||

| 6,5,6 Tricyclic pyrimidines and indoles | ||

| [18F]-T807 (Chien et al. 2013; Xia et al. 2013) |

|

• Tracer with broadest clinical data package |

| • Cortical retention consistent with the known distribution of tau in AD brain | ||

| • Strong correlation with disease severity | ||

| • Slower kinetics than 18F-T808 | ||

| • Off-target activity (striatum, choroid plexus) | ||

| [18F]-T808 (Chien et al. 2014) |

|

• Faster kinetics than 18F-T807 |

| • Substantial defluorination | ||

| Pyrrolo-pyridine-isoquinolineamine | ||

| [18F]-MK-6240 (Walji et al. 2016) |

|

• Good in vitro binding affinity to NFTs, high selectivity to β-amyloid, and excellent physicochemical properties for brain penetration and cellular permeability. |

| • No off-target binding and suitable in vivo pharmacokinetics | ||

| • Clinical studies are currently underway | ||

AD alzheimer’s disease

Future development of tau tracers will require further evaluation of existing radiotracers, including preclinical characterisation, validation in the clinic, better understanding of uptake patterns in healthy controls, test-retest and human dosimetry data, and neuropathological correlations with PET, as well as head-to-head comparisons between different tracers. Improvement seems possible in the pharmacokinetic properties of 18F-labeled tracers, binding selectivity, and experience in non-AD tauopathies.

Overall, the combination of Aβ and tau-PET is currently significantly improving the knowledge of the interactions between the two proteins in humans. In addition, tau-PET–in its unique role as a marker of neurodegeneration–may allow the in vivo study of tau pathology evolution and topographic distribution across diseases. Tau imaging could also allow early, more accurate diagnosis, and more importantly monitoring of disease progression, in other tauopathies, cognitive impairment, movement disorders, and head trauma. Tau-PET may also lead to more efficient development of disease-modifying drugs not only for compounds targeting the tau protein itself.

Detection of α-synuclein

Investigation of α-synuclein and TDP-43 in post-mortem human brains has led to increased understanding of the evolution of neuropathology in PD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, in which lesions are believed to spread from an initial ‘seed’ of misfolded protein (Jucker & Walker 2013). There is therefore a clinical need for imaging modalities for detection of α-synuclein, which has a potential role in the differential diagnosis of PD, dementia with Lewy bodies, progressive supranuclear palsy, and multiple system atrophy. Genetic biomarkers in these conditions, while critically important in the case of inherited disease, are not salient in the majority of cases (>90 %) with sporadic PD. Detection methods for α-synuclein in CSF are currently under development, although it is not clear how CSF levels relate to histopathology data (Mollenhauer 2014) and still need further validation.

Another role for α-synuclein imaging is to decrease risk and increase efficiency in drug discovery. Imaging could identify patients early enough for potential therapies, assist with therapeutic monitoring, and enhance trial recruitment and patient enrichment. α-synuclein has advantages over dopamine as a biomarker for PD, as changes in α-synuclein may occur earlier than dopamine changes, and are not up-or down-regulated by symptomatic treatment. Efforts to develop PET or single-photon emission computed tomography tracers for α-synuclein are ongoing but are still in their infancy. The compounds currently investigated for imaging α-synuclein depositions are shown in Table 3. Research groups started with the investigation of the 18F-labeled compound BF-227 that was reported to bind to both synthetic α-synuclein aggregates as well as β-amyloid fibrils in vitro (Fodero-Tavoletti et al. 2009). It was demonstrated that BF-227 could stain α-synuclein-containing glial cytoplasmic inclusions in post-mortem tissues. Moreover, a PET study with 11C-labelled BF-227 showed its ability to detect α-synuclein deposits in the living brains of patients with multiple system atrophy (Kikuchi et al. 2010). However, the high affinity of this radiotracer for β-amyloid plaques limit its use in humans for differential diagnosis.

Table 3.

Characteristics of published a-synuclein deposition tracers

| Tracer name | Chemical structure | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Aminothiazolyl-ethenyl-benzoxazole derivatives | ||

| [11C] BF-227 (Kikuchi et al. 2010) |

|

• Non-selective, affinities: see below for 18F-derivative |

| • Investigated in MSA patients | ||

| [18F] BF-227: (Fodero-Tavoletti et al. 2009) |

|

• Aß1-42 fibrils: KD1 = 1.3 nM |

| • α-syn fibrils: KD = 9.6 nM | ||

| Phenothiazine derivatives | ||

| SIL23 (Bagchi et al. 2013) |

|

• Affinity and selectivity not optimal for in vivo imaging |

| • Affinity α-synuclein: Ki = 58 nM | ||

| • Screening tool | ||

| [18F] 2b (Zhang et al. 2014) |

|

• Affinity α-synuclein: Ki = 49 nM |

| • Selectivity α -syn vs. Aß: 2-fold | ||

| • Selectivity α -syn vs. tau: 2.5-fold | ||

| • Crosses blood–brain-barrier in healthy cynomolgus macaques | ||

| • Shows sufficient initial uptake and wash-out | ||

| • Higher selectivity desired | ||

| [11C] 2a (Zhang et al. 2014) |

|

• Affinity α-synuclein: Ki = 32 nM |

| • Selectivity α-syn vs. Aß: 3-fold | ||

| • Selectivity α-syn vs. tau: 4-fold | ||

| • Crosses blood–brain-barrier in cynomolgus macaques | ||

| • Shows sufficient initial uptake and wash-out | ||

| • Higher selectivity desired | ||

| 3-(Benzylidene) indolin-2-one derivatives | ||

| [18F] 46a: (Chu et al. 2015) |

|

• Selective for α-synuclein: |

| o α-syn Kd = 8.9 nM | ||

| o Aß Kd = 271 nM | ||

| o Tau fibrils: 50 nM | ||

| • High logP and presence of nitro group may limit its use for in vivo PET studies | ||

| • Potential as secondary lead compound for further SAR studies | ||

A series of phenothiazine derivatives was described for α-synuclein-binding (Yu et al. 2012) and the radioiodinated compound SIL23 was developed (Bagchi et al. 2013). As stated by its developers, the affinity of SIL23 for α-synuclein and its selectivity for α-synuclein versus Aβ and tau fibrils is not optimal for imaging fibrillar α-synuclein in vivo, but it could be used to screen additional ligands for suitable affinity and selectivity. Following this approach, additional compounds such as [11C] 2a and [18F] 2b have been identified that are more specific for α-synuclein and have shown the ability to cross the blood–brain barrier in animal studies (Zhang et al. 2014). However, these have not yet translated to human imaging. More recently, the same group reported the development and in vitro characterization of (benzylidene) indolin-2-one derivatives as new ligands for α-synuclein fibrils covering also PET ligands like [18F] 46a with high affinity and selectivity for α-synuclein (Chu et al. 2015). Future research will show whether some of these compounds have the ability to image α-synuclein depositions in patients.

Conclusions

Several PET tracers for detection of pathological protein depositions or aggregates are now available for routine clinical use. In particular, PET agents binding to Aβ plaques are approved as an adjunct to other diagnostic evaluations to estimate the plaque density in patients with cognitive impairment who are being evaluated for AD or other causes of cognitive decline. Tau-PET tracers are currently in clinical development, and α-synuclein protein deposition tracers are at early stage of research. Importantly, PET tracer development and imaging of protein aggregates require different approaches to those involved in imaging of receptors or transporters, including lead optimisation, scan analyses and quantitation. These tracers have, and will continue to, change our understanding of complex disease processes.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Dan Booth PhD (Bioscript Medical Ltd) and funded by Piramal Imaging GmbH, Berlin, Germany. Histopathology images of TDP-43 inclusions, Tau tangles and Aβ deposits were kindly provided by Professor Walter Schulz-Schaeffer (Goettingen, Germany).

Authors’ contributions

AJ, NK, AM, and AS developed the presentation on which this manuscript is based, and were involved in the drafting and final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

AJ is an employee of Piramal Imaging GmbH, Berlin. NK, AM, and AS are employees of, and holds property rights/patents for (radio) pharmaceuticals with, Piramal Imaging GmbH, Berlin.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

Beta-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SUV

Standardized uptake value

- TDP-43

43 kDa Tar DNA-binding protein

- Aβ42

Beta-amyloid beta (1–42)

References

- Bagchi DP, Yu L, Perlmutter JS, et al. Binding of the radioligand SIL23 to a-synuclein fibrils in Parkinson’s disease tissue establishes feasibility and screening approaches for developing a Parkinson disease imaging agent. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Argyrophilic grain disease: frequency of occurrence in different age categories and neuropathological diagnostic criteria. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 1998;105:801–819. doi: 10.1007/s007020050096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catafau AM, Bullich S. Amyloid PET imaging: applications beyond Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Transl Imaging. 2015;3:39–55. doi: 10.1007/s40336-014-0098-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien DT, Bahri S, Szardenings AK, et al. Early clinical PET imaging results with the novel PHF-tau radioligand [F-18]-T807. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34:457–468. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien DT, Szardenings AK, Bahri S, et al. Early clinical PET imaging results with the novel PHF-tau radioligand [F18]-T808. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38:171–184. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu W, Zhou D, Gaba V, et al. Design, synthesis and characterization of 3-(Benzylidene) indolin-2-one derivatives as ligands for α-synuclein fibrils. J Med Chem. 2015;58:6002–17. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Beach TG, et al. Cerebral PET with florbetapir compared with neuropathology at autopsy for detection of neuritic amyloid-beta plaques: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:669–678. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cselényi Z, Jönhagen ME, Forsberg A, et al. Clinical validation of 18 F-AZD4694, an amyloid-β-specific PET radioligand. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(3):415–24. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.094029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis C, Gamez JE, Singh U, et al. Phase 3 trial of flutemetamol labeled with radioactive fluorine 18 imaging and neuritic plaque density. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:287–294. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delacourte A. Biochemical and molecular characterization of neurofibrillary degeneration in frontotemporal dementias. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(Suppl 1):75–79. doi: 10.1159/000051218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorbala S, Vangala D, Semer J, et al. Imaging cardiac amyloidosis: a pilot study using 18F-florbetapir positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:1652–1662. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2787-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eli L. Amyvid. Summary of product characteristics. Houten: Eli Lilly Nederland BV; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fawaz MV, Brooks AF, Rodnick ME, et al. High affinity radiopharmaceuticals based upon lansoprazole for PET imaging of aggregated tau in Alzheimer’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy: synthesis, preclinical evaluation, and lead selection. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5:718–730. doi: 10.1021/cn500103u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Mulligan RS, Okamura N, et al. In vitro characterisation of BF227 binding to alphasynuclein/Lewy bodies. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;617:54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GE Healthcare . Vizamyl. Summary of product characteristics. Little Chalfont: GE Healthcare Limited; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Glenner GG. Amyloid deposits and amyloidosis. The beta-fibrilloses (first of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1980;302:1283–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198006053022305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada R, Okamura N, Furumoto S, et al. Comparison of the binding characteristics of [18 F] THK-523 and other amyloid imaging tracers to Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada R, Okamura N, Furumoto S et al. 18F-THK5351: a novel PET radiotracer for imaging neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease. J Nucl Med. 2015. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto H, Kawamura K, Igarashi N, et al. Radiosynthesis, photoisomerization, biodistribution, and metabolite analysis of 11C-PBB3 as a clinically useful PET probe for imaging of tau pathology. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1532–1538. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.139550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, Holtzman DM. Biomarker modeling of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2013;80:1347–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker M, Walker LC. Pathogenic protein seeding in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:532–540. doi: 10.1002/ana.22615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker M, Walker LC. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2013;501:45–51. doi: 10.1038/nature12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepe V, Bordelon Y, Boxer A, et al. PET imaging of neuropathology in tauopathies: progressive supranuclear palsy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36:145–153. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi A, Takeda A, Okamura N, et al. In vivo visualization of alpha-synuclein deposition by carbon-11-labelled 2-[2-(2-dimethylaminothiazol-5-yl) ethenyl]-6-[2-(fluoro) ethoxy] benzoxazole positron emission tomography in multiple system atrophy. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 6):1772–8. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung HF. The beta-amyloid hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease: seeing is believing. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:265–267. doi: 10.1021/ml300058m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau SM, Fero A, Baker SL, et al. Measurement of longitudinal beta-amyloid change with 18 F-florbetapir PET and standardized uptake value ratios. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:567–574. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.148981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama M, Shimada H, Suhara T, et al. Imaging of tau pathology in a tauopathy mouse model and in Alzheimer patients compared to normal controls. Neuron. 2013;79:1094–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matías-Guiu JA, Cabrera-Martin MN, Matías-Guiu J, et al. Amyloid PET imaging in multiple sclerosis: an (18) F-florbetaben study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:243. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:709–735. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohorko N, Bresjanac M. Tau protein and human tauopathies: an overview. Zdrav Vestn. 2008;77(II):34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mollee P, Law WP, Wang WYS, Moore PT. Ng ACT. Cardiac amyloid imaging with 18F-florbetaben positron emission tomography: a pilot study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(3):e187. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2015.07.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer B. Quantification of alpha-synuclein in cerebrospinal fluid: how ideal is this biomarker for Parkinson’s disease? Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(Suppl 1):S76–S79. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(13)70020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer B, Trenkwalder C. Neurochemical biomarkers in the differential diagnosis of movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1411–1426. doi: 10.1002/mds.22510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GP, Clark IA, Vissel B. Inconsistencies and controversies surrounding the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:135. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0135-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N, Furumoto S, Harada R, et al. Novel 18 F-labeled arylquinoline derivatives for noninvasive imaging of tau pathology in Alzheimer disease. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1420–1427. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.117341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N, Furumoto S, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, et al. Non-invasive assessment of Alzheimer’s disease neurofibrillary pathology using 18 F-THK5105 PET. Brain. 2014;137:1762–1771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N, Furumoto S, Harada R, et al. In vivo selective imaging of tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease with 18F-THK5117. J Nucl Med. 2015;55(1):136. [Google Scholar]

- Piramal Imaging. Neuraceq. Summary of product characteristics. Havant: Piramal Imaging Limited; 2014.

- Ryman DC, Acosta-Baena N, Aisen PS, et al. Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;83(3):253–60. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri O, Sabbagh MN, Seibyl J, et al. Florbetaben PET imaging to detect amyloid plaques in Alzheimer disease: Phase 3 study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:964–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri O, Catafau A, Barthel H, et al. Impact of morphologically distinct amyloid β (Aβ) deposits on 18F-florbetaben (FBB) PET scans. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(3):195. [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria Bohorquez S, Barret O, Tamagnan G, et al. Identification and first-in-human evaluation of Genentech Tau Probe 1 ([18F] GTP1) Barcelona, Spain: Poster presented at the 8th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt ME, Chiao P, Klein G, et al. The influence of biological and technical factors on quantitative analysis of amyloid PET: Points to consider and recommendations for controlling variability in longitudinal data. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1050–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao X, Carpenter GM, Desmond TJ, et al. Evaluation of [(11) C] N-methyl lansoprazole as a radiopharmaceutical for PET imaging of tau neurofibrillary tangles. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:936–941. doi: 10.1021/ml300216t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields AF, Grierson JR, Dohmen BM, et al. Imaging proliferation in vivo with [F-18] FLT and positron emission tomography. Nat Med. 1998;4:1334–1336. doi: 10.1038/3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada H, Shinotoh H, Sahara N, et al. Diagnostic utility and clinical significance of tau PET imaging with [11C] PBB3 in diverse tauopathies. Miami, FL, USA: Presented at the 9th Human Amyloid Imaging Conference; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shoghi-Jadid K, Small GW, Agdeppa ED, et al. Localization of neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques in the brains of living patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:24–35. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small GW, Kepe V, Siddarth P, et al. PET scanning of brain tau in retired national football league players: preliminary findings. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smid LM, Kepe V, Vinters HV, et al. Postmortem 3-D brain hemisphere cortical tau and amyloid-beta pathology mapping and quantification as a validation method of neuropathology imaging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36:261–274. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Goedert M. Tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:609–622. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PW, Ye L, Morgenstern JL, et al. Interaction of the amyloid imaging tracer FDDNP with hallmark Alzheimer’s disease pathologies. J Neurochem. 2009;109:623–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Tau imaging: early progress and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:114–124. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walji AM, Hostetler ED, Selnick H et al. Discovery of 6-(fluoro-18F)-3-(1H-pyrrolo [2,3-c] pyridin-1-yl) isoquinolin-5-amine ([18F]-MK-6240): A Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Imaging Agent for Quantification of Neurofibrillary Tangles (NFTs) J Med Chem. 2016 Apr 18. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wong DF, Borroni D, Kuwabara H, et al. First in-human PET study of 3 novel Tau radiopharmaceuticals: [11C] RO6924963, [11C] RO6931643, and [18 F] RO6958948. Washington, DC, USA: Presented at AAIC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xia CF, Arteaga J, Chen G, et al. [(18) F] T807, a novel tau positron emission tomography imaging agent for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:666–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Cui J, Padakanti PK, et al. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of alpha-synuclein ligands. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:4625–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Jin H, Padakanti PK, et al. Radiosynthesis and Evaluation of Two PET Radioligands for Imaging alpha-Synuclein. Appl Sci (Basel) 2014;4:66–78. doi: 10.3390/app4010066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]