Abstract

Introduction:

Renin–angiotensin system (RAS) components exert diverse physiological functions and have been sub-grouped into deleterious angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)/angiotensin II (Ang II)/angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) and protective ACE2/angiotensin (1-7) (Ang-(1-7))/Mas receptor (MasR) axes. We have reported that chronic activation of angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2R) alters RAS components and provides protection against obesity-related kidney injury.

Materials and methods:

We utilized AT2R knockout (AT2KO) mice in this study and evaluated the renal expression of various RAS components and examined the renal injury after placing these mice on high fat diet (HFD) for 16 weeks.

Results:

The cortical ACE2 activity and MasR expression were significantly decreased in AT2KO mice compared to wild type (WT) mice. LC/MS analysis revealed an increase in renal Ang II levels and a decrease in Ang-(1-7) levels in AT2KO mice. Cortical expression of ACE and AT1R was increased but renin activity remained unchanged in AT2KO compared with WT mice. WT mice fed HFD exhibited increased systolic blood pressure, higher indices of kidney injury, mesangial matrix expansion score, and microalbuminuria, which were further increased in AT2KO mice.

Conclusion:

This study suggests that deletion of AT2R decreases the expression of the beneficial ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/MasR and increases the deleterious ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis of the renal RAS in mice. Further, AT2KO mice are more susceptible to HFD-induced renal injury.

Keywords: Renin–angiotensin system, angiotensin II type 2 receptor knockout, angiotensin (1-7), Mas receptor

Introduction

The renin–angiotensin system (RAS) is comprised of peptide hormones, enzymes, and receptors, which have a diverse involvement in the maintenance of sodium homeostasis and regulation of blood pressure (BP).1,2 Recently, RAS components have been sub-grouped as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)/angiotensin II (Ang II)/angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) and ACE2/angiotensin (1-7) (Ang-(1-7))/Mas receptor (MasR) axes with counter regulatory functions. While ACE/Ang II/AT1R is known to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of various cardiovascular diseases, kidney injury, anti-natriuresis, and hypertension,3–5 emerging evidence supports a protective role for ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/MasR axis in heart and kidney function, including natriuresis and hypertension.6–10 Inter-regulatory pathways have been suggested by which RAS components alter each other’s expression and function. For example, AT1R activation decreases ACE2 expression and Ang-(1-7) production11,12 leads to reduced MasR activation and function.13,14 Such changes in the RAS components cause a shift potentially impacting on the functional balance between deleterious versus protective arms of the RAS.

The angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2R) is another component of the RAS, and has not been “particularly” assigned to either of the RAS axes. However, numerous studies, including some from our laboratory, have shown that AT2R is natriuretic, anti-hypertensive, and cardio- and reno-protective in various animal models.8,15–18 Therefore, AT2R may be grouped with the protective ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/MasR axis. AT2R is termed as ‘functional antagonist’ of AT1R.19 This notion is based on the findings that AT2Rs, via dimerization with AT1R19 or cell signaling cross-talk, attenuates AT1-mediated cellular responses in various cell types including the kidney epithelial cells.20,21 Additionally, chronic treatment with AT2R agonist has been shown to cause a reduction in AT1R expression, another mechanism by which AT2R can reduce AT1R function.22 Recently, we have reported that long-term pharmacological stimulation of AT2R with preferential agonists caused a decrease in AT1R-mediated renal function, but increased the expression/activity of ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/MasR axis in the kidney cortex of obese Zucker rats.8 These changes were associated with enhanced natriuresis, lowering of BP, and decreased renal injury in obese animals.8,16 In light of the beneficial effects mediated by AT2R, the present study is designed to test the hypothesis that deletion of AT2R (a) decreases the renal expression of ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/MasR axis and increases that of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis and (b) makes the animals more susceptible to kidney injury in response to a high fat diet (HFD). To test this hypothesis, RAS components in the kidney cortices from AT2KO mice and wild type (WT) controls from a similar background were measured. To demonstrate the reno-protective effect of AT2R, WT and AT2KO mice were fed either a normal fat diet or a HFD to induce obesity-related glomerulopathy.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male AT2R–/y (AT2KO) mice, which were kindly provided by Tadashi Inagami (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA) and wild type with similar background (C57BL/6) of 20 weeks of age (purchased from Harlan, Inc.) were used in the study. The animal experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Houston. These animals were euthanized and the kidneys were removed, washed in cold saline and kept frozen at −80°C for measuring RAS components.

Western blotting for AT1R and MasR

The expression of AT1R, and MasR in the kidney cortex was determined by western blotting. For this purpose, the kidney cortices were homogenized in a buffer containing (in mM) Tris 50, ethylene diaminete tra-acetic acid (EDTA) 10, Phenyl methyl sulphonyl fluoride (PMSF) 1 and protease inhibitors. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg for AT1R and 40 μg for MasR) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and were transferred onto immobilon P (blot). The blots were incubated with primary polyclonal antibodies for the AT1R, and MasR. Following incubation with the primary antibodies, the blots were incubated with Horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit Immunoglobulin type G (IgGs). The signal was detected by Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system, recorded and analyzed by Fluorchem 8800 (Alpha Innotech Imaging System, San Leandro, California, USA) for the densitometric analysis. The blots were stripped, and re-probed with β-actin mouse monoclonal antibody.

Renin, ACE2, and ACE activity

Renin activity in the kidney cortex was measured by Sensolyte 520 Mouse renin and ACE2 activity was measured by Sensolyte 390 ACE2 assay kit (Anaspec Inc., Fremont, California, USA). The renin and ACE2 activity was determined using Mca/Dnp fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) peptide. In the FRET peptide the fluorescence of Mca is quenched by Dnp, upon cleavage into two separate fragments by the enzyme, the fluorescence of Mca is recovered, and is monitored at excitation/emission at 330/390 nm for ACE2 and at 490/520 nm for renin. ACE concentration was measured by Enzyme linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit (USCN Life Science Inc, Texas, USA) as per manufacturer’s instructions.

LC/MS quantification of angiotensin peptides

To determine angiotensin peptide levels quantitatively in the kidney cortex, tissue was homogenized in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4) with protease inhibitors. The angiotensin peptides were then analyzed by LC/MS method as described in our earlier publication.23,24

Diet-induced obesity protocol

Male WT and AT2KO mice (four weeks old) were placed either on normal diet or HFD for 16 weeks to induce obesity. The HFD feed Teklad custom research diet (TD.06414) with adjusted calorie diet (60/Fat) containing 18.4% protein, 21.3% carbohydrate and 60.3% fat, and normal diet 7022 (code of normal diet) with isocaloric 29% protein, 56% carbohydrate and 15% fat were purchased from Harlan, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. Both diets contained similar mineral mix AIN-93G-MX (94046) and vitamin mix AIN93-VX (94047). The animals were individually housed in metabolic cages during the last week of diet administration to collect urine. At the end of the 16-week treatment, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under isoflurane anesthesia following six hours of fasting. Each left kidney was fixed in formalin for histological analyses.

Renal histology and morphometry

The formalin-fixed tissue was embedded in paraffin and 4 μm sections were prepared. The slides were further stained with Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) reagents or Masson’s trichrome stain (Dako North America, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All tissue samples were evaluated independently by two investigators in a blinded fashion by light microscopy (×400). For each animal, 30 glomeruli from each of the three consecutive sections were assessed. A semi-quantitative scoring method described by Raij et al.25 was used to evaluate the degree of damage to the glomeruli. This was graded according to the severity of the glomerular damage: 0, normal; 1, slight glomerular damage of the mesangial matrix and/or hyalinosis with focal adhesion involving <25% of the glomerulus; 2, sclerosis of 25% to 50%; 3, sclerosis of 50% to 75%; and 4, sclerosis >75% of the glomerulus. A mesangial matrix expansion (MME) score was assigned in a similar manner on a scale of 0–4 depending upon the area of the glomerulus occupied by mesangial matrix when compared to lean control glomeruli. The glomerulosclerosis index or mesangial score was calculated by averaging the grades assigned to all glomeruli fields using the formula:

where N1–N4 represent the number of glomeruli with the respective score, n is the total number of glomeruli.

Measurement of microalbuminuria

An indirect competitive ELISA kit (Exocell, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) was used to measure urinary albumin excretion according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

BP

BP was measured by tail-cuff method using CODA system which is clinically validated and provides 99% correlation with telemetry and direct BP measurements.26,27 The CODA tail-cuff BP system utilizes volume pressure recording (VPR) sensor technology to measure the mouse tail BP. BP was measured during the last two weeks (three days in each week with three readings each day on each animal) of the feeding regimen. For each animal, the data for each animal was averaged and treated as one value, which was used to calculate mean±standard error of the mean (SEM).

Chemicals and reagents

Antibodies for MasR and β Actin were purchased from Alomone Labs Ltd, Israel and Santa Cruz, California, USA respectively. AT1R antibody was custom raised (Biomolecular Integration, Arizona, USA). Standards for Ang II and Ang-(1-7) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA. All other chemicals were of standard grade.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±SEM and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4 and subjected to t-test. n=5–6 in each group, as detailed in figure legends. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of deletion of AT2R on RAS components

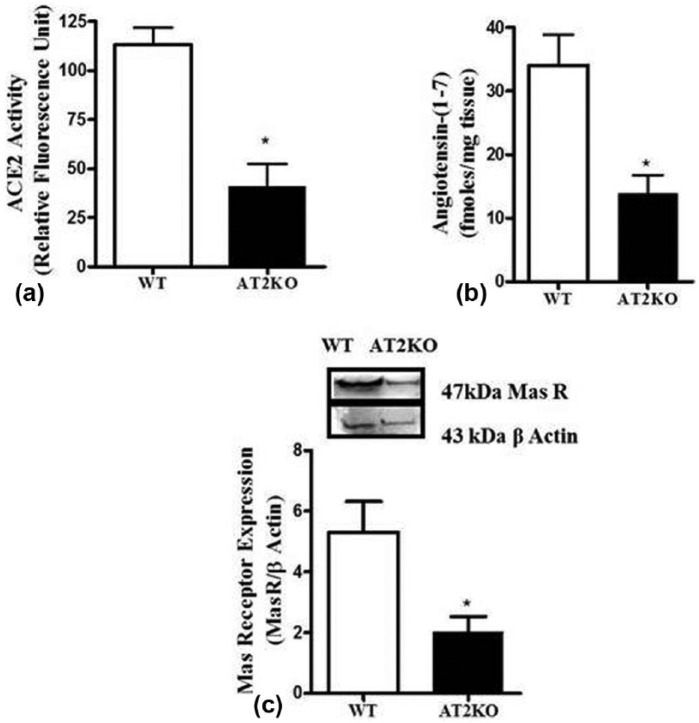

ACE2, Ang-(1-7) and MasR

The cortical ACE2 activity (Figure 1(a)) was significantly reduced (WT: 113±8, AT2KO: 41±11, RFU/min) in AT2KO mice. The LC/MS quantification of angiotensin peptides revealed that the levels of Ang-(1-7) (Figure 1(b)) was also significantly reduced (WT: 33±5, AT2KO: 14±02.8 fmoles/mg tissue) in the kidney cortex of AT2KO compared to WT mice. Similarly, cortical MasR band at 47 kDa was significantly reduced in AT2KO mice (Figure 1(c)).

Figure 1.

(a) Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)2 activity (b) LC/MS quantification of angiotensin-(1-7) and (c) Mas receptor (MasR) expression in the kidney cortex of wild type and angiotensin II type 2 receptor knockout (AT2KO) mice. Upper panels: representative western blot of MasR protein with loading control β-actin. Bar graph: represent the ratio of density of the protein band and β actin i.e. MasR/β actin *Significantly different compared with wild type (WT) mice. Values are represented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM); t-test, p<0.05; n=5 in each group.

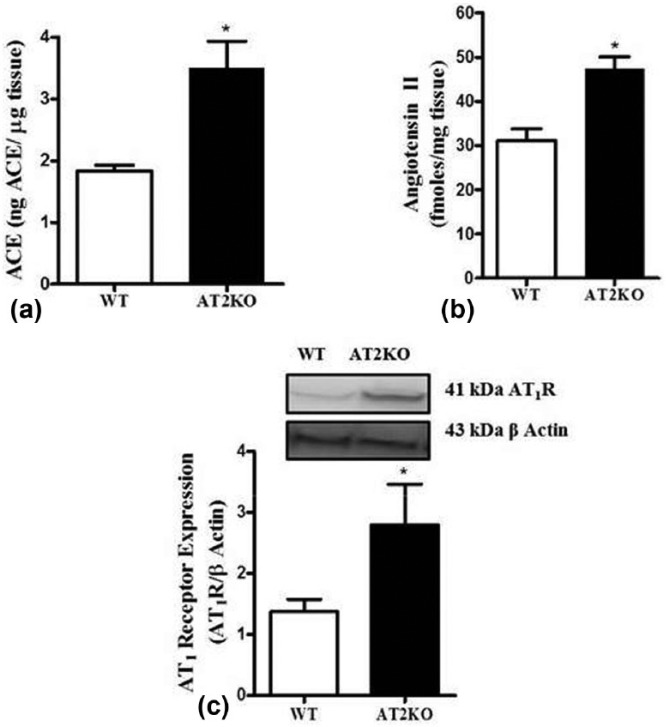

ACE, Ang II and AT1R

ACE in the kidney cortex of AT2KO was significantly elevated compared to WT mice (WT 1.9±0.02, AT2KO: 3±0.4 ng ACE/µg tissue). Ang II peptide levels (Figure 2(b)) were significantly higher in AT2KO mice kidney cortex (WT: 31±2.7, AT2KO: 47±2.7 fmoles/mg tissue). Western blot of AT1R at 41 kDa revealed almost a two-fold increase in the kidney cortex of AT2KO compared to WT mice (Figure 2(c)).

Figure 2.

(a) ACE activity (b) LC/MS quantification of angiotensin II (Ang II) and (c) angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) expression in the kidney cortex of wild type (WT) and angiotensin II type 2 receptor knock-out (AT2KO) mice. Upper panels: representative western blot of AT1R protein with loading control β-actin. Bar graph: represent the ratio of density of the protein band and β actin i.e. AT1/β actin *Significantly different compared with WT mice. Values are represented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM); t-test, p<0.05; n=5 in each group.

Renin

Renin activity in the kidney cortex remained unchanged between wild type and AT2KO mice (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Renin activity in the kidney cortex of wild type (WT) and angiotensin II type 2 receptor knock-out (AT2KO) mice. *Significantly different compared with WT mice. Values are represented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM); t-test, p<0.05; n=5 in each group.

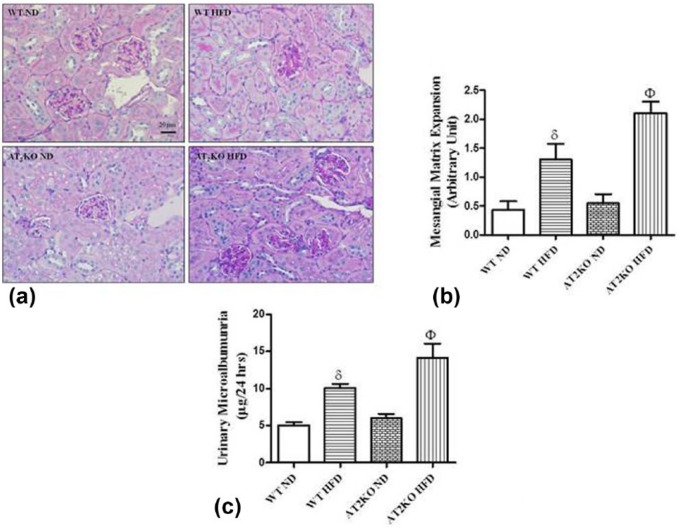

Effect of deletion of AT2R on renal injury

Markers of early renal injury

Renal sections were stained with PAS to assess glomerular injury. Early pathological changes, including glomerular hypertrophy, mesangial expansion, and basement membrane thickening, were observed in WT and AT2KO mice maintained on the HFD while the renal morphology of ND-fed WT and AT2KO mice was normal (Figure 4(a) and (b)). MME scores were higher in HFD-fed AT2KO mice compared to WT mice fed the HFD (Figure 4(a) and (b)). Masson’s trichrome stain was used to evaluate tubulointerstitial collagen deposition. No tubulointerstitial fibrosis was detected in any of the treatment groups (data not shown). WT mice on HFD excreted increased amounts of albumin in the urine, and lack of AT2R in HFD-fed mice modestly increased the urinary albumin excretion (Figure 4(c)). The urinary albumin excretion was within normal values in WT and AT2KO mice on ND (Figure 4(c)).

Figure 4.

Markers of obesity-linked early renal injury in wild type (WT) and angiotensin II type 2 receptor knock-out (AT2KO) mice. Renal morphology (a) and mesangial matrix expansion (MME) score (b) and 24-hour urinary albumin excretion (c) from WT and AT2KO mice on a normal diet (ND) or high-fat diet (HFD). Sections measuring 4 µm were stained with periodic acid Schiff (PAS) stain (magnification×400). MME score was assigned based on a semiquantitative scale described in the methods section. Data are represented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) (n=6). The symbol δ indicates p<0.05 vs WT ND and Φ indicates p<0.05 vs KO ND mice. Scale bar - 50 µm.

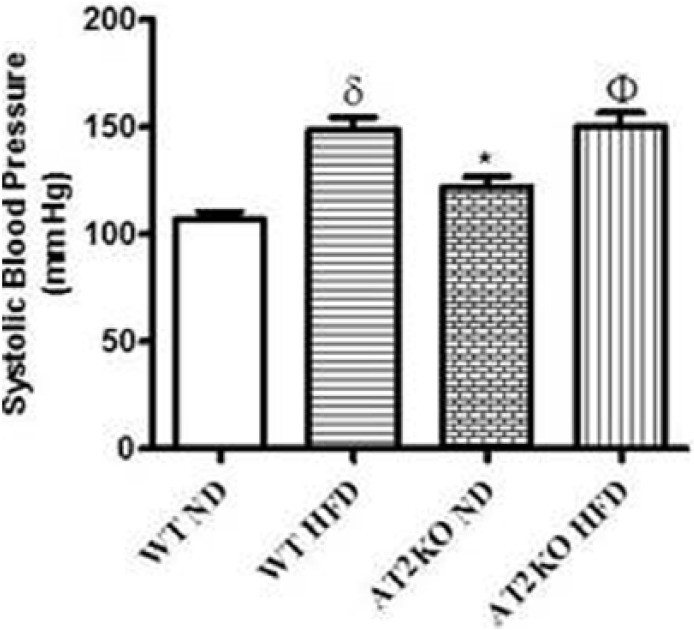

Effect of deletion of AT2R on systolic BP

As shown in Figure 5, systolic BP in AT2KO on normal diet was modestly but significantly higher compared to WT. High fat diet significantly increased systolic BP in both WT and AT2KO. However, the BP levels were similar in WT HFD and AT2KO HFD mice.

Figure 5.

Systolic blood pressure in wild type (WT) and angiotensin type 2 receptor knock-out (AT2KO) mice on a normal diet (ND) or high-fat diet (HFD). Data are represented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) (n=3–5). Both δ and * indicate p<0.05 vs WT ND, and Φ indicates p<0.05 vs KO ND mice.

Discussion

The most notable finding of the current study is that AT2R deficient mice expressed a decreased level of ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/MasR while ACE/Ang II/AT1R increased in the kidney cortex. This shift in the balance of RAS components resulted in greater susceptibility to obesity-induced renal injury, which highlights the critical role of AT2R in regulating renal RAS components and exerting reno-protective effects.

ACE2 is an important RAS enzyme which converts Ang II to Ang-(1-7). Similar to AT2R, Ang-(1-7) via the MasR, can oppose the actions of Ang II mediated via AT1R28–31 and can exert vasodilatation, natriuresis, and reno-protection. It has been shown that stimulation of MasR inhibits the AT1R-mediated regulation of ERK1/2 activity,32 a critical enzyme involved in cell growth and tissue remodeling under various pathological conditions. MasR is considered reno-protective, and blockade or deletion of this receptor has been shown to cause reduced natriuresis, increased proteinuria, and reduced renal blood flow.33–35 AT1R expression in the kidney is markedly increased along with reduced glomerular tuft diameter, increased collagen and fibronectin in MasR knockout mice.33 These findings suggest that MasR activation not only opposes the actions mediated by AT1R, but the levels of MasR may inversely influence the expression of AT1R. Adding to this RAS inter-regulatory complexity, we demonstrate for the first time that deletion of AT2R decreases ACE2 activity, MasR expression, and decreases Ang-(1-7) levels in the kidney cortex of mice. Moreover, consistent with other reports,36,37 we also observed that deletion of AT2R significantly increased AT1R expression in the kidney cortex. Additionally, Ang II levels were also elevated in the kidney cortex of AT2KO mice.

The inter-regulatory role of AT2R in the two arms of RAS seems to be complex but can be plausibly explained. The enhanced AT1R expression in AT2KO mice kidney could be a result of the reduced expression on MasR in these animals, as earlier study has shown that deletion of MasR causes an increase in the AT1R expression.33 Subsequently, it is likely that the increase in AT1R expression and activation by higher Ang II concentration, as observed in this study, causes a reduction in ACE2 expression and activity leading to the reduced Ang-(1-7) production. Earlier studies have shown such relationship in that Ang II via activation of AT1R causes a reduction in ACE2 expression and activity, thus reduces Ang-(1-7) production in cardiac myocytes.11 However, we have recently reported that the AT2R activation may have direct positive regulation of ACE2 expression and activity, without the involvement of AT1Rs.8 Thus it’s likely that AT2R may have a direct as well as indirect role in regulating the protective and deleterious arms of the RAS. However, systemic studies are needed to delineate the role of AT2R in regulating various RAS components.

The functional relevance of AT2R deletion and of the shift in the two arms of the RAS was studied in animals subjected to high fat diet, which is known to cause renal injury. As expected HFD fed WT mice developed renal injury evidenced by MME and microalbuminuria in these animals. However, AT2KO mice on HFD developed greater renal injury, suggesting a protective role of AT2R. Since AT2KO per se had no changes in MME and microalbuminuria, it could be argued that AT2R-mediated protection occurs only under pathogenic conditions, such as obesity. This notion is further supported by other studies,38 including ours,16 which show that pharmacological activation of AT2R protects against nephropathy in obese rats and diabetic animal models and had no injurious effects in normal animals. Hypertension is a known risk factor for renal injury.39 It is likely that the injury in HFD fed WT mice was related to elevated BP in these animals. However, AT2KO mice on HFD had similar elevated BP as WT HFD, yet exhibited greater renal injury, suggesting BP-independent protection by AT2R. This AT2R-mediated protection could be related to its anti-oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory activity, as reported recently.16,40 Consistent with a previous study,41 AT2KO mice had modest elevation in BP, which had no significant impact on kidney structure and albuminuria. In the present study we found an imbalance of RAS components with AT2KO without alteration in mesangial area and albuminuria. Although the levels of renal Ang II and AT1R were increased, this may not be enough to induce kidney injury and MME. In a recent study, Kim et al.,42 demonstrated that even onset of early chronic kidney disease in an experimental model is not sufficient to cause glomerular injury or collagen deposition. This suggests that a simple increase in a deleterious RAS component may not lead to kidney damage. Indeed, we have recently shown that obese rats treated with high salt leads to increase in superoxide via Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate- oxidase (NOX) and increased oxidative stress in kidney.43 Superoxide can directly affect the glomerular barrier and increases Na reabsorption leading to hypertension and renal injury in obese rats and Dahl salt sensitive rats. Further, activation of AT2R by the non-peptide agonist C21 reduces the Ang II level, expression of p47phox-NOX subunit, superoxide formation and salt-sensitive rise in BP,22,43 but had no effects on Ang II levels or oxidative stress in obese rats treated with normal diet.8 This suggests that the adverse effect of AT2R deletion can be seen only under pathogenic conditions. The limitation of this study is the fact that we did not design this study to assess renal or plasma components of RAS in AT2KO HFD mice, therefore it is unclear whether RAS components have changed in response to HFD per se and whether those changes might have further contributed to the renal injury in AT2KO mice. However, collectively our data highlights the importance of AT2R under pathogenic conditions, such as obesity, where it plays a protective role. The contribution of various components of the RAS in the face of opposing changes in obesity warrants a detailed systematic study.

In summary, we observed that deletion of AT2R caused an elevation in renal ACE/Ang-II/AT1R and reduction in ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/MasR expression leading to a shift from beneficial to deleterious axis of RAS. Thus, owing to the beneficial role of renal AT2R, it could be considered as a potentially important therapeutic target in preventing obesity related renal injury.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study is supported by National Institute of Health (grant number R01-DK61578).

References

- 1. Hollenberg NK. The renin–angiotensin system and sodium homeostasis. Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1984; 6: S176–S183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacGregor GA, Markandu ND, Roulston JE, et al. The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system in the maintenance of blood pressure, aldosterone secretion and sodium balance in normotensive subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1980; 59: 95s–99s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fraune C, Lange S, Krebs C, et al. AT1 antagonism and renin inhibition in mice: Pivotal role of targeting angiotensin II in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2012; 303: F1037–F1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tallam LS, Jandhyala BS. Exaggerated natriuresis after selective AT1 receptor blockade in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Clin Exp Hypertens 2001; 23: 623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, et al. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2000; 52: 415–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kangussu LM, Guimaraes PS, Nadu AP, et al. Activation of angiotensin-(1–7)/Mas axis in the brain lowers blood pressure and attenuates cardiac remodeling in hypertensive transgenic (mRen2)27 rats. Neuropharmacology 2015; 97: 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shi Y, Lo CS, Padda R, et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) prevents systemic hypertension, attenuates oxidative stress and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and normalizes renal angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and Mas receptor expression in diabetic mice. Clin Sci 2015; 128: 649–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ali Q, Wu Y, Hussain T. Chronic AT2 receptor activation increases renal ACE2 activity, attenuates AT1 receptor function and blood pressure in obese Zucker rats. Kidney Int 2013; 84: 931–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shenoy V, Kwon KC, Rathinasabapathy A, et al. Oral delivery of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-(1–7) bioencapsulated in plant cells attenuates pulmonary hypertension. Hypertension 2014; 64: 1248–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martins Lima A, Xavier CH, Ferreira AJ, et al. Activation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/angiotensin-(1–7)/Mas axis attenuates the cardiac reactivity to acute emotional stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013; 305: H1057–H1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Regulation of ACE2 in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008; 295: H2373–H2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ohshima K, Mogi M, Nakaoka H, et al. Possible role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and activation of angiotensin II type 2 receptor by angiotensin-(1–7) in improvement of vascular remodeling by angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade. Hypertension 2014; 63: e53–e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang Y, Li B, Wang B, Zhang J, et al. Alteration of cardiac ACE2/Mas expression and cardiac remodelling in rats with aortic constriction. Chin J Physiol 2014; 57: 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iwanami J, Mogi M, Tsukuda K, et al. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/angiotensin-(1–7)/Mas axis in the hypotensive effect of azilsartan. Hypertens Res 2014; 37: 616–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ali Q, Hussain T. AT2 receptor non-peptide agonist C21 promotes natriuresis in obese Zucker rats. Hypertens Res 2012; 35: 654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dhande I, Ali Q, Hussain T. Proximal tubule angiotensin AT2 receptors mediate an anti-inflammatory response via interleukin-10: Role in renoprotection in obese rats. Hypertension 2013; 61: 1218–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kemp BA, Howell NL, Gildea JJ, et al. AT(2) receptor activation induces natriuresis and lowers blood pressure. Circ Res 2014; 115: 388–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hilliard LM, Jones ES, Steckelings UM, et al. Sex-specific influence of angiotensin type 2 receptor stimulation on renal function: A novel therapeutic target for hypertension. Hypertension 2012; 59: 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. AbdAlla S, Lother H, Abdel-tawab AM, et al. The angiotensin II AT2 receptor is an AT1 receptor antagonist. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 39721–39726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miura S, Matsuo Y, Kiya Y, et al. Molecular mechanisms of the antagonistic action between AT1 and AT2 receptors. Biochem Biophy Res Commun 2010; 391: 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferrao FM, Lara LS, Axelband F, et al. Exposure of luminal membranes of LLC-PK1 cells to ANG II induces dimerization of AT1/AT2 receptors to activate SERCA and to promote Ca2+ mobilization. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2012; 302: F875–F883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ali Q, Patel S, Hussain T. Angiotensin AT2 receptor agonist prevents salt-sensitive hypertension in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2015; 308: F1379–F1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Samuel P, Ali Q, Sabuhi R, et al. High Na-intake increases renal angiotensin II levels and reduces the expression of ACE2-AT2R-MasR axis in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2012; 303: F412–F419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ali Q, Wu Y, Nag S, et al. Estimation of angiotensin peptides in biological samples by LC/MS method. Anal Methods 2014; 6: 215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raij L, Azar S, Keane W. Mesangial immune injury, hypertension, and progressive glomerular damage in Dahl rats. Kidney Int 1984; 26: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feng M, Whitesall S, Zhang Y, et al. Validation of volume-pressure recording tail-cuff blood pressure measurements. Am J Hypertens 2008; 21: 1288–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fraser TB, Turner SW, Mangos GJ, et al. Comparison of telemetric and tail-cuff blood pressure monitoring in adrenocorticotrophic hormone-treated rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2001; 28: 831–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Santos RA, Simoes e, Silva AC, Maric C, et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2003; 100: 8258–8263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Porsti I, Bara AT, Busse R, et al. Release of nitric oxide by angiotensin-(1–7) from porcine coronary endothelium: Implications for a novel angiotensin receptor. Br J Pharmacol 1994; 111: 652–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grobe JL, Mecca AP, Mao H, et al. Chronic angiotensin-(1–7) prevents cardiac fibrosis in DOCA-salt model of hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006; 290: H2417–H2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ferrario CM, Trask AJ, Jessup JA. Advances in biochemical and functional roles of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-(1–7) in regulation of cardiovascular function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005; 289: H2281–H2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hayashi N, Yamamoto K, Ohishi M, et al. The counterregulating role of ACE2 and ACE2-mediated angiotensin 1–7 signaling against angiotensin II stimulation in vascular cells. Hypertens Res 2010; 33: 1182–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pinheiro SV, Ferreira AJ, Kitten GT, et al. Genetic deletion of the angiotensin-(1–7) receptor Mas leads to glomerular hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria. Kidney Int 2009; 75: 1184–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sampaio WO, Nascimento AA, Santos RA. Systemic and regional hemodynamic effects of angiotensin-(1–7) in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003; 284: H1985–H1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dharmani M, Mustafa MR, Achike FI, et al. Effects of angiotensin 1–7 on the actions of angiotensin II in the renal and mesenteric vasculature of hypertensive and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2007; 561: 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gross V, Schunck WH, Honeck H, et al. Inhibition of pressure natriuresis in mice lacking the AT2 receptor. Kidney Int 2000; 57: 191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang SY, Chen YW, Chenier I, et al. Angiotensin II type II receptor deficiency accelerates the development of nephropathy in type I diabetes via oxidative stress and ACE2. Exp Diabetes Res 2011; 2011: 521076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koulis C, Chow BS, McKelvey M, et al. AT2R agonist, compound 21, is reno-protective against type 1 diabetic nephropathy. Hypertension 2015; 65: 1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Whelton PK, Klag MJ. Hypertension as a risk factor for renal disease. Review of clinical and epidemiological evidence. Hypertension 1989; 13: I19–I27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sabuhi R, Ali Q, Asghar M, et al. Role of the angiotensin II AT2 receptor in inflammation and oxidative stress: Opposing effects in lean and obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2011; 300: F700–F706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ichiki T, Labosky PA, Shiota C, et al. Effects on blood pressure and exploratory behaviour of mice lacking angiotensin II type-2 receptor. Nature 1995; 377: 748–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim JH, Xie J, Hwang KH, et al. Klotho may ameliorate proteinuria by targeting TRPC6 channels in podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. May 5 2016. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2015080888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Patel SN, Ali Q, Hussain T. Angiotensin II type 2-receptor agonist C21 reduces proteinuria and oxidative stress in kidney of high-salt-fed obese Zucker rats. Hypertension 2016; 67: 906–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]