Abstract

Piriformis syndrome is an uncommon condition that causes significant pain in the posterior lower buttocks and leg due to entrapment of the sciatic nerve at the level of the piriformis muscle. In the typical anatomical presentation, the sciatic nerve exits directly ventral and inferior to the piriformis muscle and continues down the posterior leg. Several causes that have been linked to this condition include trauma, differences in leg length, hip arthroplasty, inflammation, neoplastic mass effect, and anatomic variations. A female presented with left-sided lower back and buttock pain with radiation down the posterior leg. After magnetic resonance imaging was performed, an uncommon sciatic anatomical form was identified. Although research is limited, surgical intervention shows promising results for these conditions. Accurate diagnosis and imaging modalities may help in the appropriate management of these patients.

Keywords: Anatomy, magnetic resonance imaging, piriformis syndrome, sciatica

INTRODUCTION

Piriformis syndrome is an uncommon and debilitating condition. The most common causes of this syndrome include trauma, inflammation, and degenerative changes. However, rare anatomical variations may be another source to this underlying condition.[1,2] This case report will discuss the clinical course and imaging findings of the rare Beaton Type B sciatic nerve variant that resulted in lower back pain with unilateral radicular symptoms. After extensive literature review, there appears to be only one other published case report that provides magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images with this exact anatomic variation.

CASE REPORT

A female initially presented to the clinic for lower back pain that radiated from the left buttock down to the posterior knee. Pain was particularly worse when the patient was sitting for prolonged periods of time, such as flying and driving. Symptoms persisted and gradually worsened for the past 2 years. The patient denied ever having any weakness or numbness of bilateral lower extremities. There were no other neural deficits or attributable symptoms. On physical examination, the left-shooting pain was easily reproduced with leg flexion or in the sitting position.

The patient was initially treated conservatively with physical therapy exercises and oral analgesics. However, after several months of conservative management, the patient did not have any improvement of symptoms. This prompted further diagnostic imaging. MRI of the left hip and pelvis was performed to further evaluate the etiology of the sciatic pain.

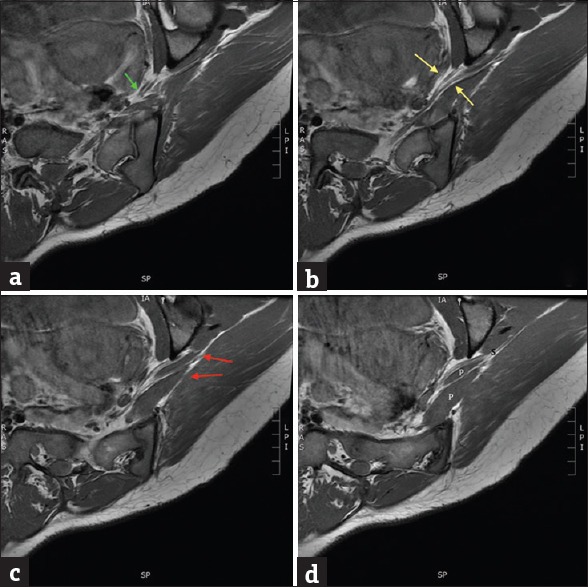

MRI images were obtained using an axial and coronal oblique plane, which is perpendicular and parallel to the sacrum bone. MRI demonstrated a piriformis muscle with split morphology and a posterior aberrant slip of the sciatic nerve that coursed through the split muscle bellies [Figure 1]. The MRI protocol used to obtain these images was adopted from the Oregon Health and Science University Radiology Department and is provided in Table 1. The piriformis muscle was without hypertrophy or significant inflammation. Based on these findings, it was determined that her sciatic pain was most likely due to nerve entrapment from the abnormal anatomic variant.

Figure 1.

A woman with lower back pain and unilateral radicular symptoms down the posterior right leg. Image (a-d) demonstrates magnetic resonance imaging T1-weighted, axial images of the pelvis, obtained at an oblique angle in respect to the sciatic nerve. (a) At the level of the pelvis, the abnormal sciatic nerve bifurcation begins to come into view (green arrow). (b) At the next oblique level, definitive split morphology of the sciatic nerve is visualized (yellow arrows). (c) Subsequent slice demonstrates the aberrant sciatic slip coursing through the split piriformis bellies (red arrows). (d) Final sequential image redemonstrates the split piriformis morphology (P) with re-joining of the two nerve segments (S).

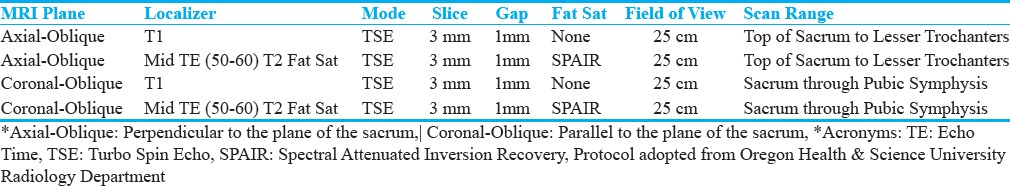

Table 1.

MRI Protocol and Sequences for the evaluation of piriformis syndrome. Protocol was adopted from Oregon Health and Science University

DISCUSSION

Piriformis syndrome is classically defined as sciatic pain due to nerve compression from muscle hypertrophy, trauma, inflammation, or neoplastic conditions.[3,4,5,6] However, in rare circumstances, anatomic variations may be the source of refractory sciatic pain. Although the variations were recognized in the early 1900s, these findings are uncommon and not readily seen on diagnostic imaging studies.

Diagnosis for this syndrome has been historically problematic due to difficulties finding objective evidence as the source of pain. It is usually a diagnosis of exclusion and made by clinical findings.[6,7] However, imaging modalities, such as MRI, have become a critical component in assisting with the diagnosis.[8] Many anatomic variants may have gone undiagnosed in the past due to the lack of or limitations of imaging studies.[9] An advanced technique of MR neurography may also be useful in aiding the diagnosis of this condition. MR neurography uses high-resolution sequences that increase the signal of peripheral nerves, which allows for increased accuracy and visualization. However, many institutions do not have this technology readily available as a diagnostic tool.

The piriformis muscle has a broad origin at the anterior sacral vertebrae and runs laterally through the greater sciatic foramen. It then inserts on the piriformis fossa at the greater trochanter of the proximal femur.[10] The sciatic nerve typically courses directly ventral and inferior to the piriformis muscle.

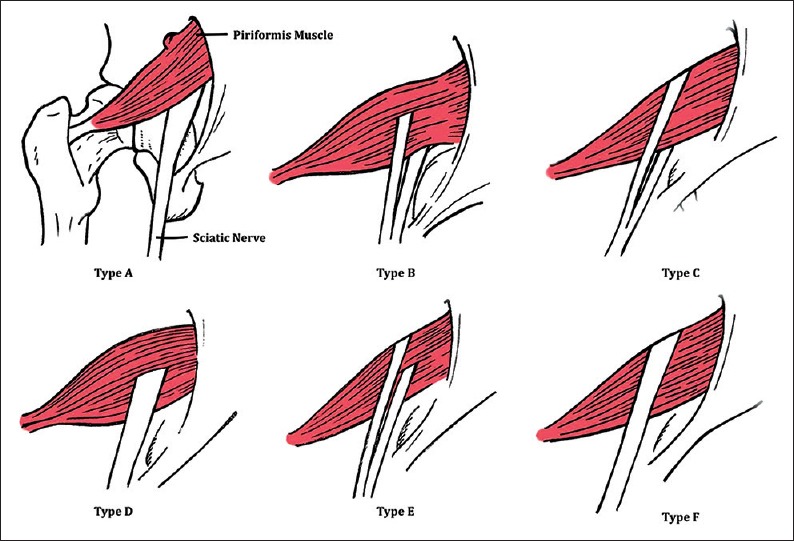

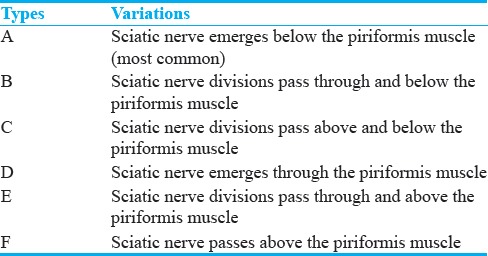

Beaton and Anson's classification system demonstrates the possible anatomic variations of the piriformis muscle and sciatic nerve. Six different anatomical variants were classified and are ordered from most common to least common.[11] Figure 2 and Table 2 demonstrate the six different types in more detail. For our case study, the patient's variant was most consistent with the Beaton Type B classification. This is best demonstrated on the T1-weighted axial imaging series [Figure 1].

Figure 2.

Six anatomic variations of the Beaton and Anson's classification system are demonstrated in this artistic rendition (posterior view). Illustrations are ordered from most common to least common, respectively, with the Type A being the most classic anatomical structure. Type B classification is the uncommon form that we find in our patient.

Table 2.

Description of Beaton and Anson's Classification System

After identifying this anatomic variation, determining the best course of management was the main topic of concern, which leads to the important research question: Is surgical intervention beneficial to a patient with refractory sciatic pain secondary to an anatomical variation?

Although there are limited data that evaluate the value of surgical intervention for anatomic variations, several studies have shown promising outcomes. A larger study by Filler et al. compared the outcomes of MRI-guided Marcaine injections versus piriformis partial resection with sciatic neuroplasty. In the injection group of 162 patients, 14.9% had prolonged relief, 7.5% had initial relief with continued relief after a second injection, 36.6% had initial relief with subsequent pain recurrence, 25.4% had minimal relief with full recurrence, and 15.7% had no response at all. Comparing that to the 62 patients who underwent surgical resection, 82% had continued relief of pain, 17% had no benefit, and 2% had worse pain.[12] Although moderate surgical benefit can be inferred from this study, the patients had different causes of piriformis syndrome and therefore may not be fully generalized to patients with anatomic variations.

According to a case report by Kosukegawa et al., a patient with a similar Beaton Type D classification had minimal relief after initial sciatic nerve block treatment. The patient subsequently underwent surgical resection of both anterior and posterior lobes of the piriformis muscle. Two years after the surgery, the patient reported complete relief and no recurrence of pain.[4]

In a more recent case report in 2016 by Kraus et al., a patient with similar split morphology of the sciatic nerve underwent a similar course of initial conservative management. The patient then proceeded with computed tomography-guided botulinum injection which resulted in minimum relief. Due to debilitating, refractory pain, the patient pursued further neurolysis with release of the sciatic nerve and partial myomectomy of the piriformis muscle. After 1-year follow-up, the patient was able to return to normal function, complete three half marathons, and endorse continued pain relief.[1]

In our young healthy patient, who failed initial conservative management, surgery was determined to be the best option to improve her quality of life. Our patient was referred to neurosurgery at a larger academic institution and will be followed up after surgical intervention is performed.

CONCLUSION

Piriformis syndrome is a debilitating and painful condition that may arise due to anatomic variations. Diagnosis is difficult to make due to limited research and objective clinical findings. However, once the diagnosis is made, determining the management is critical for the patient's quality of life. Currently, the limited literature seems to favor surgical resection over injections for refractory pain. However, it is difficult to argue that there is clear evidence-based benefit for patients with these anatomical variations. Improved imaging findings and correct diagnosis may be critical in determining best management practices in the near future.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2018/8/1/6/225958.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kraus E, Tenforde AS, Beaulieu CF, Ratliff J, Fredericson M. Piriformis syndrome with variant sciatic nerve anatomy: A Case report. PM R. 2016;8:176–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Natsis K, Totlis T, Konstantinidis GA, Paraskevas G, Piagkou M, Koebke J, et al. Anatomical variations between the sciatic nerve and the piriformis muscle: A contribution to surgical anatomy in piriformis syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36:273–80. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodrigue T, Hardy RW. Diagnosis and treatment of piriformis syndrome. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2001;12:311–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosukegawa I, Yoshimoto M, Isogai S, Nonaka S, Yamashita T. Piriformis syndrome resulting from a rare anatomic variation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:E664–6. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231877.34800.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pećina M. Contribution to the etiological explanation of the piriformis syndrome. Acta Anat (Basel) 1979;105:181–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papadopoulos EC, Korres DS, Papachristou G, Efstathopoulos N. Piriformis syndrome. Orthopedics. 2004;27:797–799. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20040801-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassidy L, Walters A, Bubb K, Shoja MM, Tubbs RS, Loukas M, et al. Piriformis syndrome: Implications of anatomical variations, diagnostic techniques, and treatment options. Surg Radiol Anat. 2012;34:479–86. doi: 10.1007/s00276-012-0940-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang HE, Park JH, Kim S. Usefulness of magnetic resonance neurography for diagnosis of piriformis muscle syndrome and verification of the effect after botulinum toxin type A injection: Two cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1504. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EY, Margherita AJ, Gierada DS, Narra VR. MRI of piriformis syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:63–4. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.1.1830063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jankovic D, Peng P, van Zundert A. Brief review: Piriformis syndrome: Etiology, diagnosis, and management. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:1003–12. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smoll NR. Variations of the piriformis and sciatic nerve with clinical consequence: A review. Clin Anat. 2010;23:8–17. doi: 10.1002/ca.20893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filler AG, Haynes J, Jordan SE, Prager J, Villablanca JP, Farahani K, et al. Sciatica of nondisc origin and piriformis syndrome: Diagnosis by magnetic resonance neurography and interventional magnetic resonance imaging with outcome study of resulting treatment. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:99–115. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.2.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]