Abstract

Cognitive behaviour therapy is a structured, time limited, psychological intervention that has is empirically supported across a wide variety of psychological disorders. CBT for addictive behaviours can be traced back to the application of learning theories in understanding addiction and subsequently to social cognitive theories. The focus of CBT is manifold and the focus is on targeting maintaining factors of addictive behaviours and preventing relapse. Relapse prevention programmes are based on social cognitive and cognitive behavioural principles. Interventions for preventing relapse include, behavioural strategies to decrease the valence of addictive behaviours, coping skills to deal with craving, arousal, negative mood states, assertiveness skills to manage social pressures, family psychoeducation and environmental manipulation and cognitive strategies to enhance self-efficacy beliefs and modification of outcome expectancies related to addictive behaviours. More recent developments in the area of managing addictions include third wave behaviour therapies. Third wave behaviour therapies are focused on improving building awareness, and distress tolerance skills using mindfulness practices. These approaches have shown promise, and more recently the neurobiological underpinnings of mindfulness strategies have been studied. The article provides an overview of cognitive behavioural approaches to managing addictions.

Keywords: Cognitive behaviour therapy, addictive behaviours, relapse prevention, self-efficacy. Mindfulness based interventions

INTRODUCTION

Addictive behaviours belong to a heterogeneous group of disorders and are associated with significant distress and disability to both the individual and family. Psychiatric co-morbidity further compounds the management of addictive behaviours.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is a structured, time limited, evidence based psychological therapy for a wide range of emotional and behavioural disorders, including addictive behaviours1,2. CBT belongs to a family of interventions that are focused on the identification and modification of dysfunctional cognitions in order to modify negative emotions and behaviours. They also include coping skills training and problem solving therapy2.

Early learning theories and later social cognitive and cognitive theories have had a significant influence on the formulation CBT for addictive behaviours. Theoretical constructs such as self-efficacy, appraisal, outcome expectancies related to addictions arising out these models have impacted treatment models considerably.

A case illustration

Rajiv a 45 year old gentleman, presented with long history of alcohol dependence. His father and maternal uncle were heavy drinkers (predispositions to drinking, social learning). Rajiv was anxious since childhood (early learning and temperamental contributions) and avoided social situations (poor coping). He started using alcohol in his college, with friends and found that drinking helped him cope with his anxiety. Gradually he began to drink before meetings or interactions (maladaptive coping and negative reinforcement). His alcohol consumption increased and began affecting his work, and functioning. He reported difficulty sleeping if he did not drink, could not get past the day without drinking or thinking about his next drink (establishment of a dependence pattern). Rajiv could not retain jobs due to frequent absence from work. His wife brought him for treatment and he was not keen on taking help He did not believe it was a problem (stage of change). He believed that drinking helped him across many domains of life (positive outcome expectancies regarding alcohol use and its effects, stage of change).

Rajiv's therapist identified antecedents associated with drinking, such as a specific friend, his brand of alcohol, the place where he usually drank, and interactions. He craved for his drink and thought about it often during the course of the day (internal and external cues to drinking and antecedents, craving, narrowing of his repertoire).

Rajiv had tried on many occasions to stop drinking, but had been unsuccessful. He reported low confidence in remaining abstinent. At start of therapy, Rajiv was not confident of being able to help himself (self-efficacy and lapse- relapse pattern).

Various psychological factors were significant in initiating and maintaining Rajiv's dependence on alcohol. At the start of treatment, Rajiv was not keen engage to in the process of recovery, having failed at multiple attempts over the years (motivation to change, influence of past learning experiences with abstinence).

His therapist identified strategies to enhance his motivation, to help him engage in therapy, deal with craving, reducing social anxiety, assertiveness and beliefs and positive expectancies about alcohol use, and confidence or sense of self-efficacy in remaining abstinent. The wife was involved in therapy, to support his abstinence and help him engage in alternate activities. Rajiv's problem is an illustration of how various psychological, environmental and situational factors are involved in the acquisition and maintenance of substance use.

Theoretical foundations and key psychological constructs

Classical conditioning models postulate that repeated pairings between affective, environmental and proprioceptive cues associated with alcohol (substance or behaviour) and the actual effects of alcohol result in the development of a classically conditioned response of withdrawal4. This response (withdrawal) is later elicited in the presence of internal or external cues (sight of a place/person associated with behaviour). Using the substance or engaging in a particular behaviour to reduce the aversive state of craving is an instrumental act5,6. The importance of conditioning in the development of craving and tolerance has been enhanced by more recent theorists and specific behavioural techniques such as cue exposure and mindfulness based strategies, that aim at tolerating craving using arousal reduction methods or ‘urge surfing’ are described7, even in behavioural addictions.

Cognitive behavioural models of substance use

The limitations of learning models, along with the growth of social learning and cognitive theories, led to the formulation of cognitive behavioural models to understand substance use. One of the best researched theories that has influence practice of CBT is the social-cognitive theory proposed by Bandura (1977). The construct of self-efficacy and outcome expectancies or beliefs associated with the consumption of substances and coping with addiction are the most significant contributions of this theoretical model8.

The cognitive behavioural perspective proposed by Beck postulates that early learning experiences (parenting, temperament, poor coping resources, and adverse events contribute to the development of core beliefs, that are in turn activated in response to critical events (failure, loss, life events, role changes) and eventually substance use is amongst other responses and symptoms. It is similar to the cognitive model of emotional disorders proposed by Beck9. Additionally, this model acknowledges the contributions of social cognitive constructs to the maintenance of substance use or addictive behaviour and relapse1.

Self-efficacy

Rajiv's unsuccessful attempts at abstinence lead to a low sense of self-confidence and a belief that he would not be able help himself (low perceived self- efficacy) setting up a vicious cycle.

Two cognitive variables that are widely researched are: a) Alcohol related outcome expectancies, which refers to anticipated effects of drinking, such as increased confidence, better sleep, feeling of high, relief from withdrawal (Rajiv believed that drinking made him more confident, less tension). b) Self efficacy expectancies, refers to an individual's beliefs about his or her ability to successfully execute a coping response in a given situation (10). The concept of self-efficacy is central to many health behaviours requiring self-regulation on the part of the individual8,9. Perceived self-efficacy is an important variable in the relapse prevention models outlined in the later sections of this chapter.

Cognitive behavioural interventions in addictive disorders

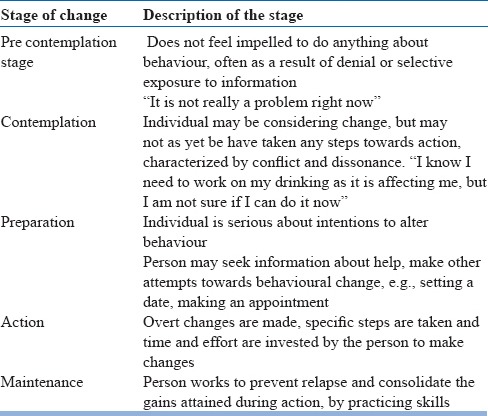

The Trans theoretical model (TTM), describes stages of behavioral change, processes of change and the decisional balance and self-efficacy which are believed to be intertwined to determine an individual's behaviour11. TTM is an integral part of relapse prevention programmes.

An individual progresses through various stages of changes and the movement is influenced by several factors. Stages imply a readiness to change and therefore the TTM has been particularly relevant in the timing of interventions. Matching interventions to the stage of change at which an individual is, can maximize outcome. For example, Rajiv did not recognize alcohol as a problem. The therapist therefore planned to improve his motivation for seeking help and changing his perspective about his confidence (motivational interviewing). Each of the five stages that a person passes through are characterized as having specific behaviours and beliefs.

There are no specific time frames within which a person navigates through the stages, and may also remain at stage for a long time before moving forwards or backwards (for example a person may remain in the stage of contemplation or preparation for years without moving on to action). Patterns of movement through the various stages are categorized as stable, progressive or unstable11.

Planning a cognitive behavioural programme

The first step in planning a cognitive behavioural treatment program is to carry out a functional analysis to identify maintaining antecedents and set treatments targets, select interventions.

As seen in Rajiv's case illustration, internal (social anxiety, craving) and external cues (drinking partner, a favourite brand of drink) were identified as triggers for his craving. Subsequently inadequate coping and lack of assertiveness and low self-efficacy maintained his drinking. The following section presents a brief overview of some of the major approaches to managing addictive behaviours.

Table 1.

Stages of Change

Behavioural interventions

Several behavioural strategies are reported to be effective in the management of factors leading to addiction or substance use, such as anxiety, craving, skill deficits2,7.

Cue exposure is another behavioural technique based on the classical conditioning theory and theories of cue reactivity and extinction12,13. The technique involves exposure to a hierarchy of cues, which signal craving and subsequently substance use. These are presented repeatedly without the previously learned pattern of drinking so as to lead to extinction. Despite work on cue reactivity, there is limited empirical support for the efficacy of cue exposure in recent literature14.

Social Skills Training

Social skills training (SST) incorporates a wide variety of interpersonal dimensions15. SST is particularly useful when patients return to drinking due to social pressures. Patients may also require communication skills to deal with interpersonal conflicts.

Training in assertiveness involves two steps, a minimal effective response and escalation. When the minimal effective response (such as informing friends that “I do not drink”) is not sufficient to bring about change, the individual is instructed to escalate to a stronger response, such as warning, threat, involving others' support. Role play, behavioural rehearsal and modeling are used to train patients in assertiveness. Patient is instructed not to provide explanations for abstinence so as to avoid counter arguments. Specific training steps to suit patients in the Indian setting have been described16,17. Family and significant others are involved in the program.

Environmental manipulation and behavioural counseling

Modifying social and environmental antecedents and consequences another approach to working with addictive behaviours18. Therapeutic strategies such as contingency management, differential reinforcement of incompatible and alternate behaviours and rearrangement of environmental cues that set the occasion for addictive behaviour, including emotional triggers are used in this approach. Family members are counselled so as identify potential risk factors for relapse, such as emotional and behavioural changes. Dealing effectively with interpersonal problems in the family, and improving communication and avoiding conflicts have been effectively employed in the Indian context16,17.

Enhancing motivation

Motivational Interviewing (MI) and motivational enhancement therapy (MET) are approaches that target motivation and decisional balance of the patient. Motivational interviewing (MI19,20) was developed in the context of behavioural trials for self-control for drinking and includes principles of expressing empathy, rolling with resistance and avoiding non- constructive arguments or conversations, supporting self-efficacy and developing discrepancy between desired life goals and substance use. Although MI incorporates the principles of the trans theoretical model, it has been distinguished from both trans theoretical model and CBT21. The efficacy of MI in addictive behaviours is well-established22,23. Motivation enhancement therapy (MET) is a brief, program of two to four sessions, usually held before other treatment approaches, so as to enhance treatment response24. MET adopts several social cognitive as well as Rogerian principles in its approach and in keeping with the social cognitive theory, personal agency is emphasized.

Problem solving therapy (PST) is a cognitive behavioural program that addresses interpersonal problems and other problem situations that may trigger stress and thereby increase probability of the addictive behaviour. The four key elements of PST are problem identification, generating alternatives, decision making, implementing solutions, reviewing outcomes and revising steps where needed. Problem orientation must also be addressed in addition to these steps, and the efficacy of PST increases when problem orientation is addressed in addition to the other steps25,26.

Relapse prevention

Relapse prevention (RP) is a cognitive behavioural treatment program, based on the relapse prevention model27,28. A psycho-educational self-management approach is adopted in this program and the client is trained in a variety of coping skills and responses. Maladaptive beliefs and expectancies are modified using cognitive techniques. The client is also encouraged to change maladaptive habits and life style patterns. The model incorporates the stages of change proposed by Procahska, DiClement and Norcross (1992) and treatment principles are based on social-cognitive theories11,29,30.

The relapse prevention model discriminates between a lapse and relapse. Relapse is seen as transitional process and not an endpoint or an outcome failure. The lapse process consists of a series of internal and external events, identified and analyzed in the process of therapy. Therapy focuses on providing the individual the necessary skills to prevent a lapse from escalating into a relapse31. A heightened sense of self-efficacy that is important to remain abstinent.

Relapse is a process in which a newly abstinent patient experiences a sense of perceived control over his/her behaviour up to a point at which there is a high risk situation and for which the person may not have adequate skills or a sense of self-efficacy. Self- efficacy increases and the probability of relapsing decreases when one is able to cope with this situation31.

The individual's reactions to the lapse and their attributions (of a failure) regarding the cause of lapse determine the escalation of a lapse into a relapse. This phenomena is known as the absence violation effect (AVE). The abstinence violation effect is characterized by two key cognitive affective elements. Cognitive dissonance (conflict and guilt) and personal attribution effect (blaming self as cause for relapse). Individuals who experience an intense AVE go through a motivation crisis that affects their commitment to abstinence goals30,31.

Three important factors are identified as being responsible for relapse. Negative emotional states, such as anxiety, depression, anger, boredom are often dealt with by using substances, interpersonal conflicts that the person cannot cope with effectively or resolve and the social -pressure to use a substance31. Others high risk situations include physical states such as hunger, thirst, fatigue, testing personal control, responsivity to substance cues (craving). The RP model highlights the significance of covert antecedents such as lifestyle patterns craving in relapse.

Treatment strategies in the relapse prevention

The relapse prevention programme combines a variety of cognitive behavioural strategies33. It skills training such as behavioural rehearsal, assertiveness training, communication skills to cope with social pressures and interpersonal problem solving to reduce impact of conflicts, arousal reduction strategies such as relaxation training to manage pain or anxiety as risk for relapse. Cognitive reframing of lapses, coping imagery for craving and life style interventions, such as physical activity are used to help develop skills to deal with craving and broaden the patient's behavioural repertoire. Cognitive restructuring techniques are employed to modifying beliefs related to perceived self-efficacy and substance related outcome expectancies (“such as drinking makes me more assertive”, “there is no point in trying to be abstinent I can't do it”). Strengthening self-efficacy is important to reduce probability of relapse. The RP programme is individualized based on the initial assessment.

Other models of relapse prevention also draw upon the construct of self-efficacy34. It is now believed that relapse prevention strategies must be taught to the individual during the course of therapy, and various strategies to enhance patient involvement and adherence such as increasing patient responsibility, promoting internal attributions to events are to be introduced in therapy. Working with a variety of targets helps in generalization of gains, patients are helped in anticipating high risk situations33.

Cognitive strategies in managing addictive behaviours

According to Beck et al., (2005), “A cognitive therapist could do hundreds of interventions with any patient at any given time”1). A careful functional analysis and identification of dysfunctional beliefs are important first steps in CBT. The hallmark of CBT is collaborative empiricism and describes the nature of therapeutic relationship.

With regard to addictive behaviours Cognitive Therapy emphasizes psychoeducation and relapse prevention. Therefore, many of the techniques discussed under relapse prevention that aim at modification of dysfunctional beliefs related to outcomes of substance use, coping or self-efficacy are relevant and overlapping.

One helpful cognitive strategy in the initial phase of CBT includes using the Advantage/disadvantage technique with the patient29. The therapist and patient collaboratively review the advantages/disadvantages of engaging in substance use or addictive behaviour. This technique also aims to develop cognitive dissonance.

Negative automatic thoughts (NATs) are a central target in CBT. Patients are taught to identify NATs by recording their thoughts as they occur using self-monitoring and to generate alternative responses using the Socratic dialogue. The patient is encouraged to respond to these automatic thoughts using a variety of verbal responses, that is different from already established problem behaviours.

In CBT for addictive behaviours cognitive strategies are supported by several behavioural strategies such as coping skills.

Mindfulness based approaches to relapse prevention

A more recent development in the area of managing addictive behaviours is the application of the construct of mindfulness to managing experiences related to craving, negative affect and other emotional states that are believed to impact the process of relapse34.

Mindfulness, is drawn from Zen Buddhist teachings and refers to viewing things in a special way. The mechanisms of mindfulness include being non-judgemental, acceptance, habituation and extinction, relaxation and cognitive change35. These variables are essential in developing distress tolerance and reducing impulsivity, which are important variables in relapse process.

The Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP36,37) integrates mindfulness meditation practices with cognitive behavioral relapse prevention skills (e.g. identifying high-risk situations; coping skills training30. Mindfulness practice is central to MBRP and is the primary focus38. This programme is similar to other mindfulness based interventions such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and Dialectic Behaviour Therapy (DBT) in that it involves practices that enhance awareness and acceptance39. There is as yet limited empirical evidence for the MBRP. The neurobiological basis of mindfulness in substance use and craving have also been described in recent literature40.

Summary and future directions

Despite various treatment programmes for substance use disorders, helping individuals remain abstinent remains a clinical challenge. Cognitive behavioural therapies are empirically supported interventions in the management of addictive behaviours. CBT comprises of heterogeneous treatment components that allow the therapist to use this approach across a variety of addictive behaviours, including behavioural addictions. Relapse prevention programmes addressing not just the addictive behaviour, but also factors that contribute to it, thereby decreasing the probability of relapse. Addictive behaviours are characterized by a high degree of co-morbidity and these may interfere with treatment response.

Mindfulness based interventions or third wave therapies have shown promise in addressing specific aspects of addictive behaviours such as craving, negative affect, impulsivity, distress tolerance. These components are particular relevant in behavioural addictions. These interventions integrate both cognitive behavioural and mindfulness based strategies. Cultural adaptation of therapeutic programmes developed in western are important. Family and significant others are an integral part of the treatment program. The greatest strength of cognitive behavioural programmes is that they are individualized, and have a wide applicability.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beck JS, Leise BS, Najvatis LM. Cognitive therapy. In: Frances MJ, Miller SI, Mack A, editors. Clinical text book of affective disorders. New York: Guildford Press; 2005. pp. 475–501. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McHugh RK, Hearon BA, Otto MW. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2010;33(3):511–525. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.012. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobson KS, editor . Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludwig AM. Pavlov's “bells” and alcohol craving. Addictive Behaviors. 1986 Jan 1;11(2):87–91. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West R. MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. Theory of addiction; pp. 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel S. US: Springer; 1983. Classical conditioning, drug tolerance, and drug dependence. In Research advances in alcohol and drug problems; pp. 207–246. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiluk BD, Carroll KM. New Developments in Behavioral Treatments for Substance Use Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013 Dec;15(12) doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0420-1. doi:101007/s11920-013-0420-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Penguin; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A. A socio cognitive analysis of substance abuse: An Agentic Perspective. Psychol Sci. 1999;10:3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ. Coping-Skills Training and Cue-Exposure Therapy in the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23(2):107–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue reactivity in addition research. Addiction. 1999;94:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botvin GJ, Wills TA. Personal and social skills training: Cognitive-behavioral approaches to substance abuse prevention. Prevention research: Deterring drug abuse among children and adolescents. 1985;63:8–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasadarao PSDVP, Mishra H. Behavioural intervention in Alcohol Dependence: Towards a multidimensional approach. NIMHANS Journal. 1994;12:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramesh S, Kumaraiah V. Behavioural interventions in alcohol: A social skills and training perspective. NIMHANS Journal. 1994;15:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller WR. Controlled drinking. A history and a critical review. J Stud Alcohol. 1983;44(1):68–83. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1983.44.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2009;37(2):129–40. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. doi:10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a Theory of Motivational Interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. doi:10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: twenty-five years of empirical studies. Res Soc Work Pract. 2010;20(2):137–160. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller WR, Baca LM. Two-year follow-up of bibliotherapy and therapist-directed controlled drinking training for problem drinkers. Behavr Ther. 1983;14:441–448. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Project MATCH Research Group. Project MATCH: Rationale and methods for a multisite clinical trial matching patients to alcoholism treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:1130–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connors GJ, Maisto SA, Donovan DM. Conceptualizations of relapse: a summary of psychological and psychobiological models. Addiction. 1996;91:5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Zurilla TJ, Goldfried MR. Problem solving and behavior modification. J Abnorm Psychol. 1971 Aug;78(1):107–26. doi: 10.1037/h0031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nezu AM, Nezu CM, D’Zurilla . Problem solving therapy: a treatment manual. NY: Springer Publishing Manual LLC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marlatt GA, George WH. Relapse Prevention: Introduction and Overview of the Model. Brit J Addiction. 1984;79:261–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendershot CS, Witkiewitz K, George WH, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for addictive behaviors Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2011;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marlatt GA, Gordon JR, editors. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marlatt GA, Barrett K, Daley DC. Relapse prevention. The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. (2nd ed) 1999:393–407. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larimer ME, Palmer RS, Marlatt AG. An Overview of Marlatt’ s Cognitive-Behavioral Model 1999. Alcohol Research and Health. 23(2):151–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludgate JW. Treatment maintenance and relapse prevention. In: Bellack A. S, Hersen M, editors. Exeter: Comprehensive Clinical Psychology Pergammon Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Annis HM. A relapse prevention model for treatment of alcoholics. In: Miller W.R, Heather N, editors. Treating Addictive Behaviors: Processes of Change. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 407–433. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, Wang MC. Efficacy of relapse prevention: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:563–570. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.563. PubMed: 10450627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marlatt GA. Buddhist philosophy and the treatment of addictive behavior. Cogn Behav Pract. 2002;9:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baer R. Mindfulness Training as a Clinical Intervention: A Conceptual and Empirical Review. Clin Psychol Sci Prac. 2003;0:125–143. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowen, Chawla N, Marlatt GA. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for addictive behaviors: A clinician's guide. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, Grow J, Chawla N, Hsu SH, Carroll HA, Harrop E, Collins SE, Lustyk MK, Larimer ME. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):547–56. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witkiewitz K, Lustyk KBM, Bowen S. Re-Training the Addicted Brain: A Review of Hypothesized Neurobiological Mechanisms of Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(2):351–365. doi: 10.1037/a0029258. doi:10.1037/a0029258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]