Abstract

Recent research points to a shift from categorical diagnoses to a dimensional understanding of psychopathology and mental health disorders. In parallel, there has been a rise in newer psychosocial treatment modalities, which are inherently transdiagnostic. Transdiagnostic approaches are those that identify core vulnerabilities and apply universal principles to therapeutic treatment. As treatment of substance use disorders (SUD) must invariably accommodate such vulnerabilities, clinicians are finding such interventions useful. Therapies like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), Metacognitive Therapy, Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP) use a transdiagnostic framework and are backed by evidence in the last 3-5 years. In this paper we first highlight the conceptual understanding of SUD through these frameworks and then discuss their clinical applications along with specific techniques that have been particularly useful with this population.

Keywords: Third wave interventions, Dialectical behaviour therapy, radical acceptance, dialectical abstinence, Acceptance Commitment Therapy, Schema Therapy

INTRODUCTION

As we move toward recognizing addiction within the background of multiple emotional, behavioural, interpersonal and personality concerns, current generation interventions have gained momentum.[1,2] Within a transdiagnostic framework, psychopathology is viewed as cross-cutting, in a continuum from normal to problematic, dimensional rather than categorical, which allows for greater flexibility in recognition of heterogeneity within diagnoses as well as co-morbidity between disorders.3 Large-scale research now provides strong evidence for the presence of at least four broad spectra of disorders, including schizoid, somatoform, internalizing and externalizing syndromes, with the latter comprising typically of substance use, conduct disorders, adult antisocial behaviours, attention deficit hyperactive disorder, intermittent explosive disorder and oppositional defiant disorder, many of which often co-occur. Furthermore, these have been found to have personality traits including negative affect, antagonism, hostility and detachment to varying levels that impact functioning. Current approaches such as third wave therapies have therefore expanded or modified traditional approaches to include interventions such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), Metacognitive Therapy, Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention and Dual Focused Schema Therapy. Other interventions such as solution focused therapy and narrative therapy have also found significant utility. These suggest that ACT is almost as efficacious as traditional approaches (CBT, 12-step programme, Nicotine replacement therapy etc.).4 There is substantial evidence for DBT in clients, particularly adolescents with Borderline Personality disorder with substance abuse.5 Dual focused schema therapy has shown promising evidence when tested with 12-Step Facilitation Therapy, group drug counseling and individual drug counseling.6,7,8 Narrative therapy has been customized to work with those who abuse substance and their families, and techniques such as externalizing the problem and writing letters have gained popularity.9,10,11

Theoretical Background and therapy focus

The existing current generation therapies provide a comprehensive working model wherein substance use is viewed as a means of coping with affect dysregulation.12 An example would be of an individual who smokes cannabis to cope with the sadness of a recent break-up. If one were to dig deeper, this would have otherwise been a person who was always lived on the edge, mostly got her/his way and found it difficult to delay gratification. The choice of the coping method one takes is also such that it gives instant relief from sadness without having to go through the cumbersome task of processing emotions or talking it out.

When it comes to substance use disorders, more often than not we see co-occurring disorders such as personality disorders, anxiety spectrum disorders and mood disorders. It is well known now that individuals with personality vulnerabilities such as impulsivity, risk taking or its converse, being avoidant, or of being high on neuroticism are more likely to experiment with substances such as marijuana13. These vulnerabilities classified as internalizing and externalizing disorders themselves have an overlap (correlation of 0.5).13

Research now indicates that traditional taxonomies which are categorical have significant limitations because psychopathology itself is not a discrete entity. Also, all those who are distressed but do not fall under a diagnostic label cannot be denied care. Dimensional models are finding more usefulness in clinical practice and research.3

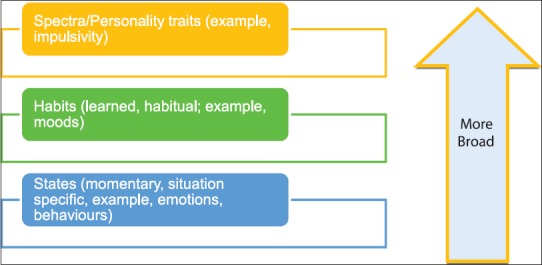

Third wave therapies due to their inherently transdiagnostic framework, allow for a broader scope to understand an individual.4 The interventions move from understanding of one's states and habitual routines to broad patterns or constellations of personality traits and spectra of behaviours.14 The framework provides a rich contextual knowledge to work on the person's self-concept, their relationships, and ability to find meaning and purpose in life.15

The theoretical underpinnings of transdiagnostic and third wave therapies are aimed at teaching clients' skills that focus on two main things: change and acceptance. They also consider experiential avoidance, i.e. active attempts by a person to avoid negative thoughts and emotions; as an unhealthy way of coping. Acceptance strategies include reality orientation, observing and describing thoughts, emotions, behaviours and environments in a non-judgmental manner. On the other hand, change strategies include cognitive restructuring, exposure, contingency management and problem-solving skills.

Conceptual understanding of substance use problems

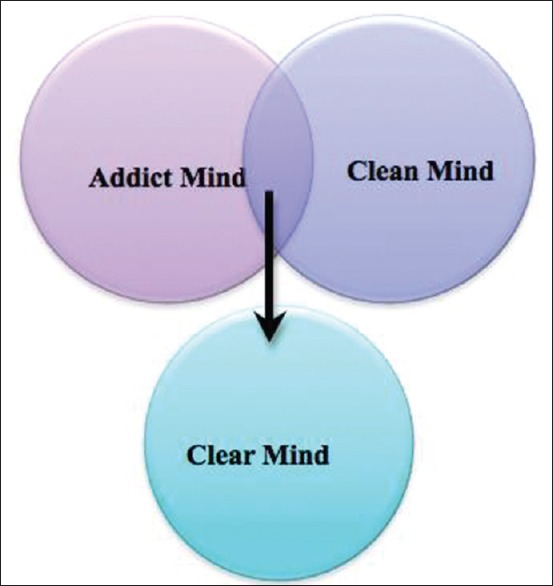

As explained earlier, the theoretical underpinnings of third wave therapies focus on change and acceptance. DBT emphasizes on a “clear mind” by acceptance of the dialectics of an “addict mind” and “clean” mind, wherein a person is fully aware of urges, accepts them and learns how to cope with them.16 It also aims at decreasing life threatening and problem behaviors while increasing problem-solving skills.5 ACT conceptualizes SUD as disorders of ‘avoidance’ since a person is trying to cope with problems and uncomfortable emotions in one's life by using. The overlap between how an individual wants to be and how they actually are, based on his/her own values is called ‘workability’. Emphasis is on ‘acceptance’ and ‘willingness' to build new strategies so as to lead a meaningful life based on his/her true values.17

Schema therapy understands addiction as a behavioural response to the thoughts and feelings that emerge when a maladaptive schema is triggered. The schema may be that of entitlement, failure to achieve, insufficient self-control, approval seeking or abandonment to which the person may either give in or avoid or fight against using substances.18

Finally, we must highlight the fact that these interventions not only aim at abstinence from substances as their outcomes but also for the individual to have an enhanced quality of life by meaning-making.4,5

Structure and duration

The interventions are structured and also available in manualized forms. Depending on the choice of therapy and client's needs, the duration of sessions range from 4-30 spanning over a period of 1-12 months.

Application and techniques

It must be kept in mind that all the techniques used must foster the aim of either change or acceptance in the client. The overall outcome of therapy is to develop a strong sense of self-awareness and then eventually build new meanings to a person's life.

1. Emotion Recognition and Regulation

We have constantly observed that almost all clients present with complaints of one or more of anger dyscontrol, anxiety, guilt or disgust. Some go on to recognize that substances, especially alcohol19 and heroin help them numb their emotional pain, allowing them to cut off from themselves, whereas some do not. To make therapy more meaningful, as a first step, it becomes essential to facilitate insight and connect the dots between unbearable emotions and use of substances. It is during this process that many of them, who seem to have been self-medicating through their use, experience an “aha” moment. This must be followed up by interventions for emotional regulation.

Clients often have difficulty in labeling which emotions they are experiencing, or reading the emotions of others. They also experience multiple emotions simultaneously, and have difficulty processing them. Linehan, in her work on “emotional regulation” in DBT, provides a very specific yet detailed method to help clients first recognize feelings to be on a continuum and with increased awareness builds skills in them to manage painful emotions.

A useful way to work with this is to make them maintain a mood-emotion chart. It is also important to help them recognize that each emotion itself varies from a continuum of low to high and see where they are currently and how much variation they experience on a day-to-day basis, followed by how they act upon them.

An example that can be provided to the client to explain emotions:

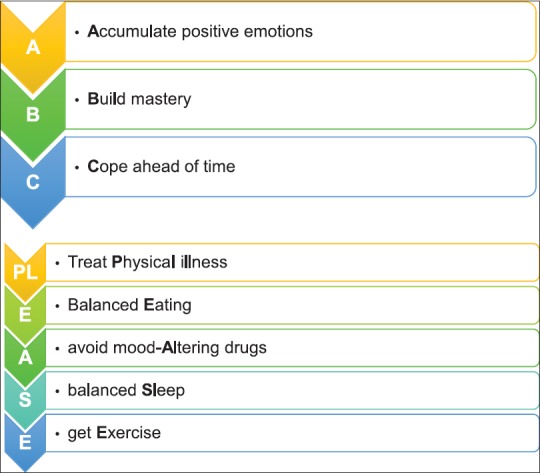

Once the emotion is identified, the triggers associated with it are focused on. This leads to self-validation and the person gains a new understanding. Through this, they can identify that they tend to act quickly on these emotions. Their problem behaviours may have been a function of how they experience and perceive these emotions rather than what happens in reality. Eventually, clients learn to use their “wise mind” which is a balance between using only one's emotions (known as emotion mind) or using only logic (known as rational mind),19 leading to behavioural changes. It helps to develop one's own inner resources while making choices regarding drugs, saying no to peers, approving of newer relationships or jobs and is inherently more intuitive. The therapist plays a key role in helping the client reach to this state of wisdom in a compassionate manner by using stories, and metaphors. For example, “when one is offered lemons, make lemonade” is a phrase often used to explain how even difficult times can be reinterpreted to one's benefit. DBT is also helpful to reduce emotional vulnerability so that a client would be more resilient in difficult moments. These include conflicts at home, a deadline at work, parties or a crisis. One such technique is known as ABC PLEASE.

Figure 1.

Levels of Intervention

In ACT, struggling with difficult feelings is akin to struggling in quicksand, the more one tries, the quicker one sinks. Teaching the client to put off the “struggle switch” causes him/her to allow emotions to move freely and not waste time fighting them. Instead of constantly judging them, they learn to acknowledge them as a stream of sensations and urges. They then make room for acceptance of these emotions by using techniques like urge surfing, acceptance self-talk or acceptance imagery20 which are described below.

2. Imagery work, dealing with craving

In contrast to craving management techniques from traditional models which are delay, distract, discuss etc., third wave therapies ask clients to accept urges and be aware of them. The more one suppresses them the greater is the force with which they return.20 When the client gets craving and a thought pops up “I want to drink right now, its unbearable”, ACT asks the person to replace it with “I am getting a thought that I want to drink right now, its unbearable”. This change in statement makes a shift in the associated emotion, without suppressing it.

As a reality acceptance technique, urge surfing or “riding the wave” is a method that allows clients to go with the flow of the impulse and live it till its end. Like a wave that will eventually ebb down, the clients are taught that so would the craving for the substance. This is especially useful for highly addictive substances such as nicotine and opiates.

Figure 2.

“Addict” mind, “Clean” mind and “Clear” mind

Narrative therapy goes on to externalize the problem of craving and makes the client even personify it, some use a name like ‘the devil’ or a ‘bad spirit’.21 This imagery helps to think of the problem as external, something she can fight and thereby causing one not to think of it as their own fault. It also looks at unique outcomes when the client might not have given into craving.21 These methods decrease self-blame and reinforce self-efficacy.

3. Mindfulness

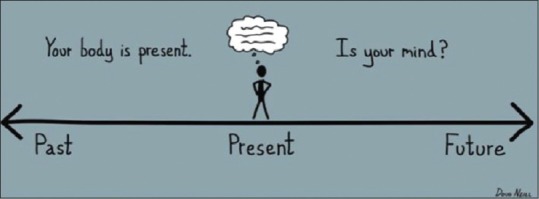

Mindfulness based relapse prevention (MBRP) integrates cognitive-behavioural strategies along with mindfulness meditation practices. It aims to equip the client with skills to handle her/his triggers and to reach a heightened sense of self-awareness that changes their relationship with internal experiences like thoughts, feelings, physical sensations and external experiences which are bound to the environment.22

Mindfulness based exercises for relapse prevention, increases awareness of body arousal, without having to necessarily act on it.22 It asks the client to imagine standing on a beach and the urges, negative thoughts and emotions come like strong waves carrying a lot of current, but instead of being swept away by the tide, the person can firmly stand on the ground, allowing the waves to come and go away.9 Instead of changing the content of the thoughts like in CBT, mindfulness changes the person's relationship with these thoughts.4 With practice clients, become familiar with their internal experiences and come to realize that they have a choice to pause and return to the present moment.22 Neither do they dwell on the past mistakes nor do they live forward, busy making decisions for the future.23 It encourages clients to break out of the “auto-pilot” mode wherein they first experience, second judge and third react to a “pause” mode wherein they experience, do not judge and do not react yet remain aware of each shift within them. In this form of meditation, one pays attention to the present moment only and experiences it through all the five senses. Practicing mindfulness especially in high-risk situations without acting out impulsively or giving into it by using the substance again leads to increased self-efficacy.23

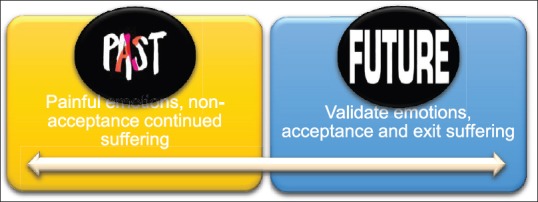

4. Reality Orientation/Radical Acceptance

Reality orientation is a means by which clients do not actively go into solving the problem nor do they stay miserable, but rather accept reality. This is especially useful to allow the client to let go past events. For example, an 18-year-old woman, abusing heroin and always felt that her parents were partial towards her older brother. Now, due to her increased use and abusive behavior, her parents decide to move in with the brother, letting her stay alone. This causes in her extreme feelings of rejection and abandonment. She became more abusive towards them. The thought of them made her hate herself more. After exploring her feelings of how she had failed as a daughter in her view, and what experiences had let to these feelings, the therapist helped her validate her emotions and accept her reality as a sum of the conditions in the environment and her own contribution to it. Subsequently, the therapist looked for top 2-3 reasons for her anger, and provides exposure to these situations deliberately, while the client calmed herself down by doing a breathing exercise. She was also exposed to their pictures causing her to be in contact with her emotions. Instead of repeatedly thinking, “Why did I not have a good relationship with my parents?” “I should have got that job” which act as triggers to substance use, the client learns to understand and accept reality. This helped her move to the next step of working at the troubled relationship.24

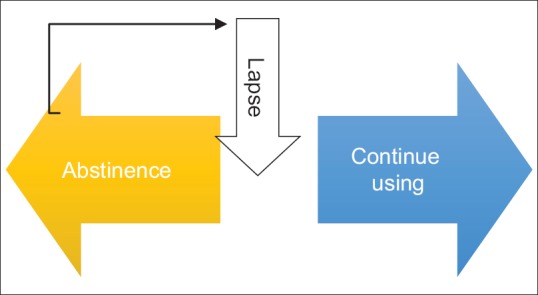

5. Dialectical Abstinence

Dialectical Abstinence encompasses holding two contrasting elements in one view, like using and being clean (See figure 8). Here the therapist asks the client to immediately and permanently stop using the substance without any exceptions yet prepares the client for a slip. This can be thought of as a harm reduction strategy by preventing a lapse from turning into a relapse. The analogy used is that of person climbing an icy trail to be safe when caught up in a snowstorm.24 If one stops climbing s/he may die, a slip could be fatal, so all the energy is focused on climbing and even if there is a fall, the person gets up and continues climbing. A timed approach is used in which a person sets the goal to 100% abstinence for a duration that is possible and easy; for example, it could even be five minutes, one hour or one month.25 The therapist and client set the goal of complete abstinence here, however in case a lapse occurs, the therapist responds non-judgmentally and facilitates problem-solving methods motivating the person to go back to the previous state of abstinence rather that thinking “I’ve anyway blown it away so what's the point? Let me continue using” (abstinence violation effect).

Figure 8.

Dialectical Abstinence

Figure 3.

Emotions on a continuum

Figure 4.

Emotion regulation using ABC PLEASE of DBT

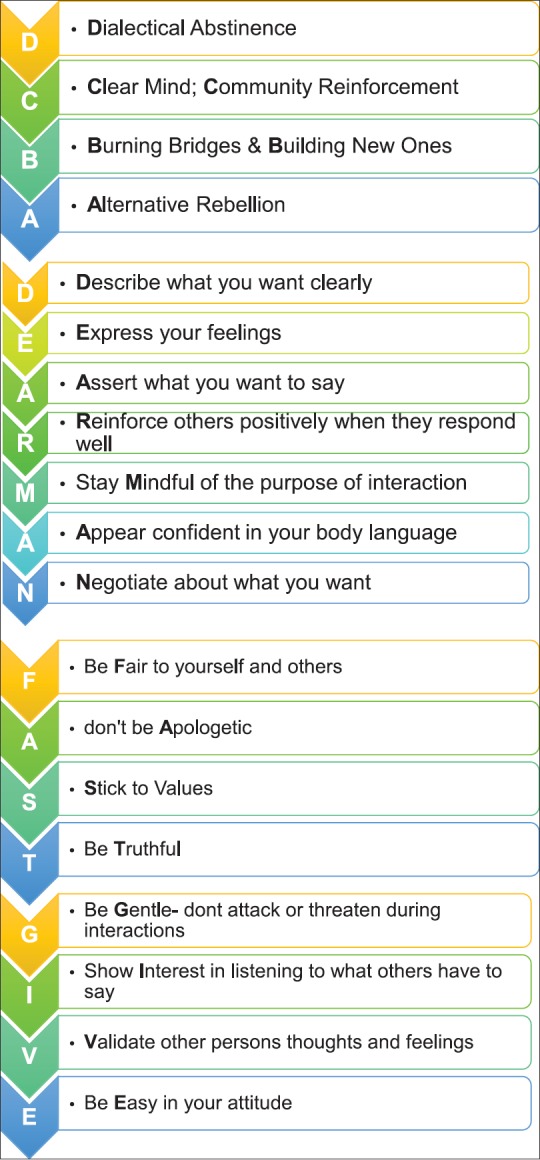

6. Building interpersonal relationships

Having a good social support system is recognized as one of the most vital components in recovery. While our clients have to mend family ties, take on the task of rebuilding their trust, and handle the expected criticality, hostility and reminders of the past, they also need to find respite in a good support system. In their struggle towards coming out of substance use, a social support in the form of friends, family or community support can prevent a lapse from turning into a relapse. It would be very useful to have someone to talk to in the face of craving or painful emotions.

Often, clients present with difficulties in the interpersonal domain. The main aim here is three-fold: to achieve one's interpersonal goals, to maintain the health of the relationship and to keep one's self-respect. DBT encourages clients not only to build effective relationship skills like assertiveness, and other skills represented by the acronyms DEAR MAN, FAST, GIVE, but also get rid of the problematic ones. The therapist must ask about the client's using friends, if he/she were involved in selling drugs, with whom they would spend most of their time etc., and then encourage the client to minimize exposure to the drug paraphernalia, i.e. things that remind the individual of the substance like needles, syringes, rolling paper, foils, etc., This is called as “burning the bridges” to past, wherein clients avoids contact with those things that connect them back to their old life of substance abuse.16 Cognitive defusion strategies from ACT are useful in this area. Instead of thinking “All my relatives think I’m a junkie” the person may think into “Ok that is another thought that I note and observe” causing cognitive distancing.17

7. Finding meanings

The themes of people with addictions often reflect loss, failure, betrayal or hopelessness. Narrative therapy is a powerful framework of intervention where clients are invited to re-author their live stories. The therapist first elicits a story that is ‘problem-saturated’. This is followed by externalizing the problems and causing some distance. The therapist then looks for client's strengths and experience of unique outcomes where the problem did not occur. The next step would be to facilitate the client to develop an alternative storyline based on the information gathered and then the therapist thickens the ‘alternative story’. This is often done by writing letters, for example, in instances of trauma or grief, writing letters to the significant other to deal with painful memories. The alternative story brings out new meanings and shifts the client from having a narrow, blameworthy view of the problem to a broader, objective and healthy view.

Meaning making is like icing on the cake. It completes the change process bringing about new conclusions from the same past experiences. It sets the person free from his/her own assumptions, judgments and earlier burdens and marks a future journey with greater self-awareness. The process of meaning making must be carried out in a culturally sensitive manner. The person's relationship with himself/herself, i.e. with their thoughts, emotions and behaviours changes from struggle to a stance of acceptance and with increased ability to deal with problematic ones, through which, they gains greater control over their life.

Figure 5.

Urge Surfing

Figure 6.

Mindfulness

Figure 7.

Reality Orientation

Figure 9.

DCBA, DEARMAN, FAST, GIVE Skills of DBT

Case Vignette

A 19-year old adolescent was brought by his parents due to excessive use of cannabis (10-15 joints/day) since the last 1.5 years along with anger dyscontrol and threats to harm himself if he was not given money. The boy was initially resistant to therapy and to engage him into therapy, the focus was on exploring about his interests and life goals rather than the drug use (validation and building therapeutic alliance). As the client became more comfortable, he elaborated that he had not been managing his time too well and his parents had begun interfering in his life too much, which made him very upset, both at them and himself. Though he minimized his cannabis use, the client did mention that it had a calming effect on him and made it easy for him to forget what happened the previous day (affect regulation). On doing chain analysis, it was found that the anger outbursts had led to increased use of cannabis. This has caused the parents to become more controlling, again leading to a spiral of increased anger and threats of self-harm to get his way through, making it a cycle. He also shared that there were deeper emotions of guilt and shame of not having lived up to his parent's expectations, considering himself as an under achiever. The therapy focus was on emotional regulation, its association with family stressors and how these had impacted his sense of self. He was made to recognize his primary and secondary emotions and practice self-validation. He also recognized his bodily sensations and arousals during these feelings. He then went on to maintain an emotion diary to note the intensity of his emotions across situations. He was taught skills to be more accepting and be more self-aware using mindfulness practice. Role plays were used to teach him self-respect in interpersonal relationships. Toward the end of therapy, his repertoire of positive emotions was enhanced, which in turn decreased his strong craving for cannabis.

Summary and future directions

In conclusion, research trends show movement towards understanding an individual across diagnostic categories. It therefore brings the usability of transdiagnostic approaches to the forefront and offers integrative methods to therapy, backed by evidence. The techniques move beyond behavioural measures and press on making deeper, lasting changes to the client's life with increased awareness. Third-wave and other interventions have been primarily a part of western literature and there is a need to tailor them in the Indian context. This, in our minds would be easier to do again due their transdiagnostic nature. The stance of the therapist and being oriented to the client's culture is an important aspect of these interventions. More research must continue in these areas to guide further practice, along with attention to broad dimensions of pathology rather than diagnoses in research designs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sauer-Zavala S, Gutner CA, Farchione TJ, Boettcher HT, Bullis JR, Barlow DH. Current definitions of “transdiagnostic” in treatment development: A search for consensus. Behavior therapy. 2017;48(1):128–38. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahl KG, Winter L, Schweiger U. The third wave of cognitive behavioural therapies: what is new and what is effective? Current opinion in psychiatry. 2012;25(6):522–8. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328358e531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, Brown TA, Carpenter WT, Caspi A, Clark LA, Eaton NR. The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2017;126(4):454. doi: 10.1037/abn0000258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee EB, An W, Levin ME, Twohig MP. An initial meta-analysis of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for treating substance use disorders. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2015;155:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimeff LA, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for substance abusers. Addiction science and clinical practice. 2008;4(2):39. doi: 10.1151/ascp084239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball SA, Maccarelli LM, LaPaglia DM, Ostrowski MJ. Randomized trial of dual-focused versus single-focused individual therapy for personality disorders and substance dependence. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2011;199(5):319. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182174e6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball SA. Comparing individual therapies for personality disordered opioid dependent patients. Journal of personality disorders. 2007;21(3):305–21. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ball SA, Cobb-Richardson P, Connolly AJ, Bujosa CT, O’Neall TW. Substance abuse and personality disorders in homeless drop-in center clients: symptom severity and psychotherapy retention in a randomized clinical trial. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2005;46(5):371–9. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foroushani EZ, Foruzandeh E. Effectiveness of narrative therapy on mental health of addicts' wives treated in the addiction treatment centers in Khomeini Shahr. International Journal of Educational and Psychological Researches. 2015;1(4):266. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaminsky D, Rabinowitz S, Kasan R. Treating alcoholism through a narrative approach. Case study and rationale. Canadian Family Physician. 1996;42:673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark AA. Narrative therapy integration within substance abuse groups. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. 2014;9(4):511–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ritschel L. A, PhD, Lim N. E, PhD, Stewart L. M., PhD (2015) Transdiagnostic applications of DBT for adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2015;69(2):111–128. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tully E, Iacono WG. An integrative common liabilities model for the comorbidity of substance use disorders with externalizing and internalizing disorders. In The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allemand M, Flückiger C. Changing Personality Traits: Some Considerations From Psychotherapy Process-Outcome Research for Intervention Efforts on Intentional Personality Change. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2017;27(4):476–94. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer JA, Singer BF, Berry M. Springer Netherlands. 2013. A meaning-based intervention for addiction: Using narrative therapy and mindfulness to treat alcohol abuse. In The experience of meaning in life. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMain S, Sayrs JHR, Dimeff LA, Linehan MM. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Individuals with Borderline Personality Disorder and Substance Dependence. In: Dimeff LA, Koerner K, editors. Dialectical behavior therapy in Clinical Practice. New York: The Gulliford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackledge JT, Ciarrochi J, Deane F, editors. Acceptance and commitment therapy: contemporary theory research and practice. Australian Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ball SA. Treatment of personality disorders with co-occuring substance. In: Magnavita JJ, editor. Handbook of personality disorders: Theory and practice. John Wiley and Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Dijk S. DBT Made Simple: A Step-by-step Guide to Dialectical Behavior Therapy. New Harbinger Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris R. The happiness trap. 2011. Read.how.you.want. com .

- 21.Man-kwong H. Overcoming craving: The use of narrative practices in breaking drug habits. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work. 2004;2004(1):17. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowen S, Chawla N, Marlatt GA. Guilford Press; 2011. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for addictive behaviors: A clinician's guide. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA, Walker D. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for alcohol and substance use disorders. Journal of cognitive psychotherapy. 2005;19(3):211–28. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koerner K. Guilford Press; 2012. Doing dialectical behavior therapy: A practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dimeff LA, Koerner KE. Guilford Press; 2007. Dialectical behavior therapy in clinical practice: Applications across disorders and settings. [Google Scholar]