Abstract

Melanocyte differentiation antigens such as gp100, tyrosinase, and Melan-A and their corresponding antibodies HMB45, T311, and A103 are major diagnostic tools in surgical pathology. Little is known about tyrosinase-related protein 2 (TRP-2, or dopachrome-tautomerase/DCT) another melanocyte differentiation antigen which is an enzymatic component of melanogenesis. We identified a commercial reagent to TRP-2, monoclonal antibody (mAb) C-9 and undertook a comprehensive analysis to assess its specificity and usefulness for surgical pathology. Subsequently, we analyzed panels of normal tissues and tumors. We show that TRP-2 is regularly expressed in melanocytes of the normal skin. In cutaneous nevi TRP-2 is present in junctional as well as in dermal nevocytes. In malignant tumors, C-9 reactivity is restricted to melanocytic and related lesions and present in 84% and 58% of primary and metastatic melanomas respectively. Ten primary melanomas of the ano-rectal mucosa were all positive. Like the other melanocyte differentiation antigens, TRP-2 was absent in six desmoplastic melanomas. Also, only two of nine angiomyolipomas were TRP-2 positive.

We conclude that mAb C-9 is a valuable reagent for the analysis of TRP-2 expression in archival surgical pathology material. The expression pattern of TRP-2 in melanocytic and related lesions appears to parallel other melanocyte differentiation antigens though the overall incidence is lower than other antigens such as Melan-A or gp100.

Keywords: TRP-2, melanocyte differentiation antigen, dopachrome-tautomerase

INTRODUCTION

The formation of melanin pigment is a complex biological process commonly referred to as melanogenesis. Melanogenesis involves various cellular components most of which engage also in other functions, while some are restricted to melanin generation1. Those components which are restricted to melanogenesis are also called melanocyte differentiation antigens since they are solely expressed in cells and tumors of melanocytic lineage2. Melanocyte differentiation antigens exert biological functions such as structural proteins (gp100, Melan-A), enzymes (tyrosinase) or transcription factors (MITF)1. In surgical pathology, melanocyte differentiation antigens are commonly used for differential diagnosis and confirm or refute the presence of melanocytic lesions or melanocytic neoplasms. Consequently, serological reagents such as monoclonal antibody (mAb) HMB45 to gp100, mAb A103 to Melan-A, and mAb T311 to tyrosinase have become standard diagnostic tools in surgical pathology3–5. More recently, melanocyte differentiation antigens have become the center of interest in tumor immunology as targets for cancer treatment. In various clinical trials, antigens such as gp100 and Melan-A have served as targets for vaccine-based immunotherapeutic approaches in melanoma patients6–8. In this context, the exact knowledge about the expression pattern of these antigens is key.

Tyrosinase-related protein-2 (TRP-2) is another melanocyte differentiation antigen. Functionally, TRP-2 is a dopachrome-tautomerase (DCT), modifying the structure and composition of melanin9–11. Different from tyrosinase, the absence of TRP-2 does not result in lack of pigmentation but rather modifies the color of pigmentation. Recent studies indicate a role of TRP-2 in the immunology of melanoma similar to other differentiation antigens12;13.

Although ample knowledge has been acquired in surgical pathology as well as in tumor immunology about the presence of gp100, Melan-A, tyrosinase, and MITF, little is known about TRP-2, especially its distribution pattern in melanomas and related tumors as well as its potential presence in other non-melanocytic tissues and tumors14. In the present study we identified a monoclonal antibody to TRP-2, verified its specificity, and analyzed the expression pattern of TRP-2 in panels of normal and tumor tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In order to perform morphological analyses of pathological specimens and/or eligibility testing for clinical trial, a serological reagent suitable for the morphological analysis of archival pathologic material is mandatory. We identified clone C9, a commercial murine monoclonal antibody (mAb) (IgG2a; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), according to the manufacturer suitable for the analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue. To ascertain the actual properties and optimal conditions for using this novel reagent, we performed comprehensive analyses including specificity analysis and immunohistochemical optimization procedures. Various antigen retrieval procedures were tested and an optimal working dilution was established. To ensure immunopositive cells were melanocytes, C-9 immunostaining was compared in serial sections to HMB45 (DAKO, Carpentaria, CA) and anti-Melan-A mAb A103, previously generated by our group15;16. The primary antibody was detected with a biotinylated horse-anti-mouse secondary (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), followed by an avidin-biotin-complex tertiary (ABC Elite, Vector Labs). Diaminobenzidine (liquid DAB, Biogenex, San Ramon, CA) served as a chromogen; Gill’s II hematoxylin was used for counterstaining. The same detection system was used for mAb HMB45 and mAb A103. In order to confirm specificity during immunohistochemical techniques, blocking experiments were performed by incubating mAb C-9 with TRP-2 protein preparations.

ELISA

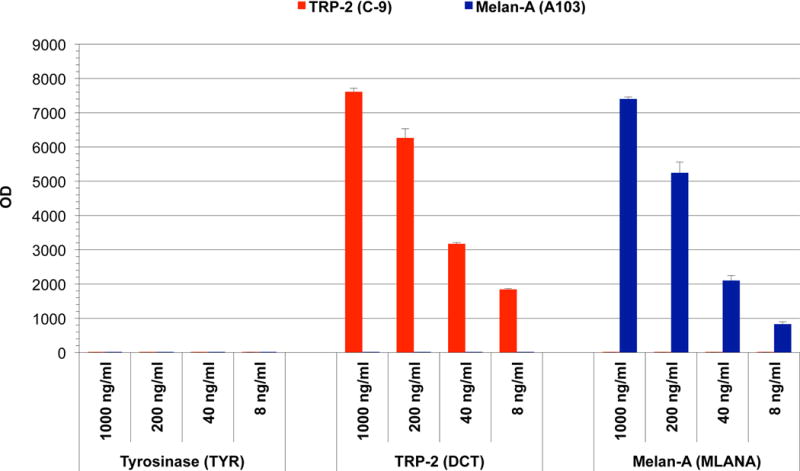

ELISA specificity analysis of mAb C-9 was performed using E. coli-produced full-length protein preparations of melanoma differentiation antigens TRP-2, tyrosinase, and Melan-A. All proteins were coated on plates at 1 μg/ml. As control antibody, mAb A103, previously generated in our lab against Melan-A, was used. Both antibodies were titrated in five-fold dilutions from 1000 ng/ml to 8 ng/ml. As a secondary, an alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG antibody (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) was used followed by development with Attophos fluorescence substrate system (Promega, Madison, WI). Antibody reactivity was measured by fluorescent intensity using a micro-plate reader (Synergy 2, BioTek, Winooski, VT) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

ELISA analysis of anti-TRP-2 mAb C-9 and anti-Melan-A mAb A103 in descending antibody concentrations with full-length protein preparations of Melan-A, Tyrosinase, and TRP-2 (1 μg/ml). Strong reactivity of mAb C-9 and mAb A103 was observed with TRP-2 and Melan-A respectively, with no cross-reactivity to other proteins.

Quantitative molecular analysis of TRP-2

In order to evaluate the presence of TRP-2 on a molecular level, and to confirm the specificity of C-9, several melanoma cell lines were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Cell lines SK-MEL-14, SK-MEL-19, SK-MEL-23, SK-MEL-26, SK-MEL-27, and SK-MEL-128, all previously generated in our institution, were retrieved from the MSKCC cell line repository. Total RNA was extracted with a commercial kit (RNeasy mini-kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and reverse transcription was performed using a cDNA synthesis kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). For the quantitative gene expression analysis, two separate primer sets amplifying regions over-spanning exons 1–2 (Taqman Hs00157244m1, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and exons 3–4 (TaqmanHs01095856m1) were used in a 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Preparations of normal skin served as reference for TRP-2 RNA levels. Corresponding formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded pellets of the molecularly analyzed cell lines were immunohistochemically analyzed with mAb C-9.

Expression analysis of TRP-2 in normal tissues and tumors

After determining the specificity for TRP-2, several tissue panels were immunohistochemically analyzed with mAb C-9. The tissues comprised of various normal tissues consisting of all parenchymal organs, and several sets of melanocytic and non-melanocytic tumors. Also, we analyzed compound nevi, malignant melanocytic lesions consisting of primary and metastatic cutaneous melanomas, mucosal melanomas from the anoreactal area, as well as desmoplastic melanomas. Furthermore, we studied a series of angiomyolipomas and a panel of malignant tumors unrelated to melanomas such as breast cancer, non-small lung cancer and others.

In tumor sections, C-9 staining was graded based on the amount of immunopositive tumor cells as follows: negative: no staining; focal: staining in <5%; +: staining in >5–25%; ++: staining in >25–50%; +++: staining in >50–75%; ++++: staining in >75% of lesional cells.

RESULTS

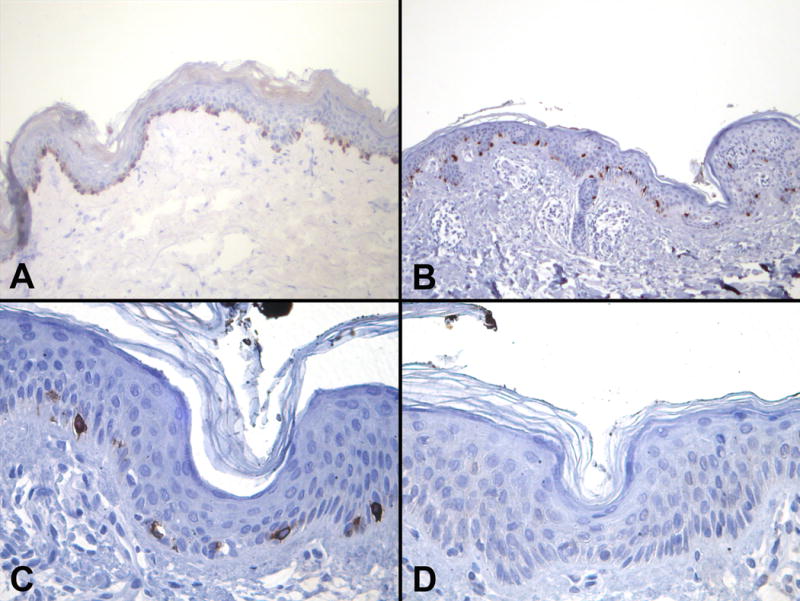

Anti-TRP-2 murine monoclonal antibody clone C-9 (SC-744439; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), designated for the use on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded material was obtained commercially. In order to confirm its suitability for immunohistochemistry, C-9 was tested on snap-frozen as well as standard archival formalin-fixed paraffin embedded skin tissue. C-9 showed strong and consistent cytoplasmic immunolabeling of melanocytes (Figure 1). The presence of C-9 immunoreactivity in melanocytes was confirmed by immunostaining of serial sections with mAbs HMB45 and A103. Optimal immunostaining with mAb C-9 was achieved at a concentration of 0.1ug/ml. For the staining of paraffin sections, slides were subjected to a heat based (99°C, 30 minutes) antigen retrieval technique by immersing slides in various buffer solutions. Optimal results were achieved employing citrate-buffer (pH6.0, 10mM), the use of higher pH buffer solutions rendered inferior immunoreactivity. Immunostaining of melanocytes could be completely blocked by pre-incubation of C-9 with 10ug/ml of TRP-2 protein in the primary reagent solution. C-9 showed strong and consistent staining of melanocytes in frozen as well as in paraffin sections (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Immunohistchochemical staining with anti-TRP-2 monoclonal antibody C-9 (avidin-biotin-method, diaminobenzidine chromogen) in skin showing strong immunopositivity of melanocytes in A) acetone-fixed frozen and B) formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded skin sections, C) high power magnification of skin with immunopositive melanocytes and D) immunonegative melanocytes after blocking with TRP-2 protein.

In ELISA analysis, mAb C-9 reactivity was solely detected with TRP-2 protein. No reactivity was seen with Melan-A or tyrosinase. Reactivity was detectable at all tested concentrations of mAb, down to 8 ng/ml. As expected, control antibody mAb A103 was positive for Melan-A and negative for tyrosinase and TRP-2 (Figure 2).

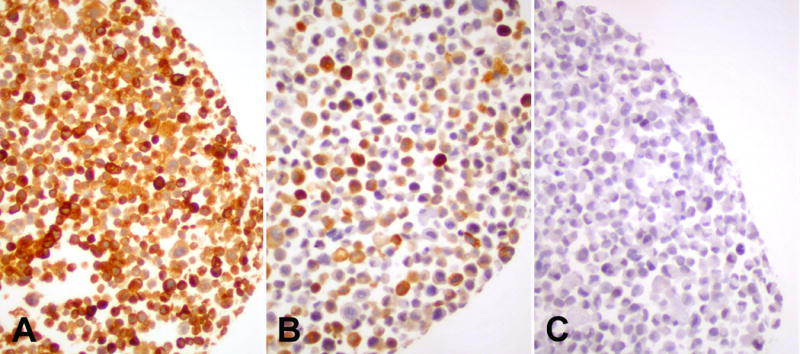

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of TRP-2 showed presence of TRP-2 RNA in all tested melanoma cell lines except SK-MEL-128, which remained completely negative. RNA levels of melanoma cell lines varied between approximately twice to ten times the level measured in skin and were congruent for both tested primer sets (Table 1). Immunohistochemical analysis of the corresponding cell line pellets showed C-9 staining in all cell lines except SK-Mel-128, which did not reveal any immunopositivity (Figure 3). The levels of RNA corresponded with the protein expression which showed intense and homogeneous immunostaining in melanoma cell lines with high TRP-2 RNA levels, less intense and heterogeneous immunopositivity in cell lines with lower RNA levels, and missing staining in SK-Mel-128 with undetectable TRP-2 RNA levels (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Quantitative RT-PCR for TRP-2 RNA in various melanoma cell lines and normal skin as reference; primer sets for amplicons in exons 1/2 (Taqman primer/probe set HS00157244m1, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and exons 3–4 (Taqman primer/probe set Hs19085856m1).

| Sample | TRP-2 Ex3–4 | TRP-2 Ex1–2 |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | 100% | 100% |

| SK-MEL-23 | 203% | 157% |

| SK-MEL-37 | 297% | 216% |

| SK-MEL-26 | 265% | 233% |

| SK-MEL-19 | 592% | 450% |

| SK-MEL-14 | 1073% | 839% |

| SK-MEL-128 | 0% | 0% |

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded pellets of melanoma cell lines with anti-TRP-2 mAb C-9 displaying A) homogeneous expression in SK-Mel-14, B) heterogeneous expression in SK-Mel-26, and C) no expression in SK-MEL-128 (avidin-biotin-method, diaminobenzidine chromogen).

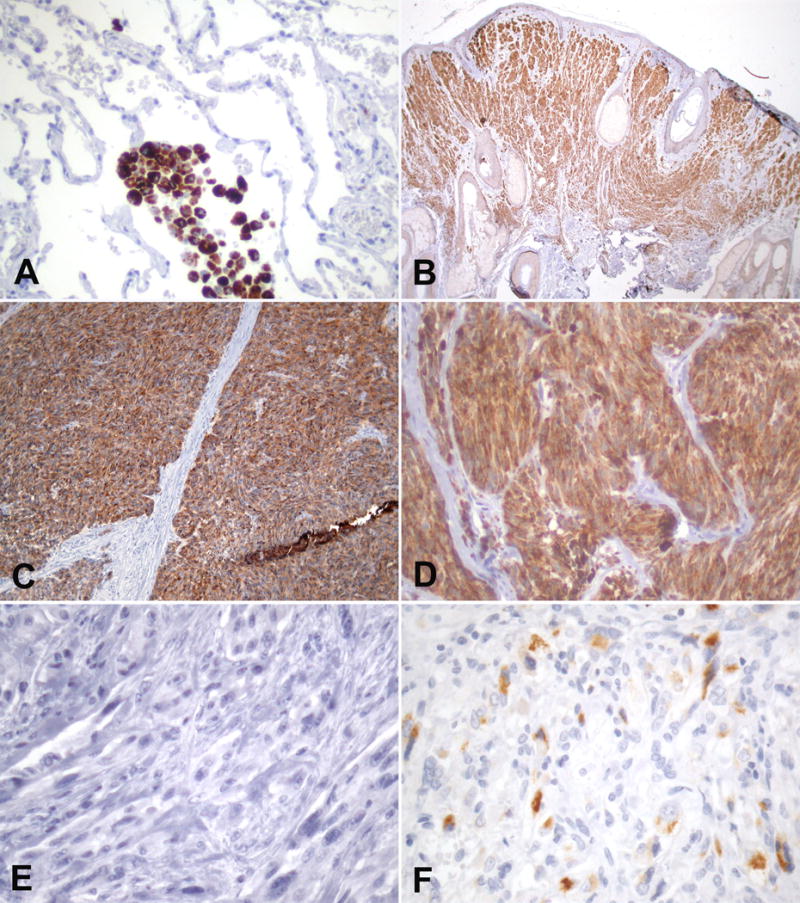

In the immunohistochemical analysis, C-9 showed the typical staining pattern of melanocytes in skin. Outside skin, C-9 showed very little immunoreactivity in parenchymal organs. In lung, there was occasional granular staining in the alveolar macrophages (Figure 4). The actual lung parenchyma was negative. In liver, there was occasional and focal heterogeneous labeling of lipofuscin granules of hepatocytes. However, most hepatocytes and other cellular components remained completely negative. Tissues of other organs such as kidney, colon, pancreas, fatty tissues, and smooth muscle in various locations were all negative.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of anti-TRP-2 mAb C-9 in A) lung displaying granular reactivity of alveolar macrophages, B) compound dermal nevus with strong staining of all nevocytes, homogenous strong TRP-2 in primary C) and metastatic D) melanoma, E) negative desmoplastic melanoma, and focal TRP-2 positive cells in F) renal angiomyolipoma.

In order to evaluate the presence of TRP-2 in non-malignant lesions of the skin, we analyzed 10 compound nevi. C-9 showed homogeneous staining of the dermal as well as the junctional component. We further analyzed C-9 in a variety of malignant melanocytic lesions (Table 2). C-9 was positive in the 16/19 (84%) of nineteen primary melanomas. The presence of TRP-2 varied and approximately half of the analyzed cases displayed homogeneous expression, i.e. TRP-2 positivity in more than 50% of the tumor area, corresponding to 3+ and 4+ immunostaining of our grading system. In metastatic melanoma, TRP-2 was expressed in 19/33 (58%) of the tested cases. As in primary melanomas, approximately 50% of the positive cases showed homogeneous expression. We also tested ten melanomas of the anorectal mucosa available, which were all positive for C-9. However, six desmoplastic melanomas remained completely negative. Besides the melanocytic lesions, we also studied nine angiomyolipomas of the kidney. Only 2/9 showed very restricted reactivity with mAb C-9 (Table 2, Figure XY). In order to test for any reactivity of mAb C-9 in other tumors, we analyzed five cases each of a series of non-melanoctyic malignant tumors consisting of: lobular breast carcinoma, ductal breast carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder, liposarcoma, and non-small cell lung cancer. All non-melanocytic tumors were negative for mAb C-9 (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of TRP-2/DCT expression in various types of melanoma and angiomyolipoma with monoclonal antibody C-9 (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX).

| C-9 Immunoreactivity | Primary Melanoma | Metastatic Melanoma | Melanoma of the Anorectal Mucosa | Desmoplastic Melanoma | Angiomyolipoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 3/19 | 14/33 | 0/10 | 6/6 | 7/9 |

| Positive | 16/19 (84%) | 19/33 (58%) | 10/10 | 0/6 | 2/9 |

| Focal (<5%) | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |

| + (5%-25%) | 5 | 5 | 1 | ||

| ++ (25%-50% | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| +++ (50%-75%) | 3 | 4 | 2 | ||

| ++++ (>75%) | 6 | 5 | 4 |

DISCUSSION

Malignant melanoma is among the most deadly cancers in humans. For its correct diagnosis as well as treatment, comprehensive understanding of the processes and the components underlying the generation of melanin pigment are mandatory. Melanocyte differentiation antigens are pivotal components in the biology of pigment generation. Based on this role, melanocyte differentiation antigens play an important role in surgical pathology and have emerged as potential vaccine targets for the treatment of melanoma. Serological reagents such as HMB45 to gp100, A103 to Melan-A, and T311 to tyrosinase have become household names as diagnostic tools in pathology labs. Though its gene was cloned several decades ago, little is known about tyrosinase-related protein 2, which is better known by its abbreviated name TRP-217. TRP-2 is the human homologue of the murine slaty locus and part of the tyrosinase complex. The latter is the cellular biological correlate of pigment generation and consists of tyrosinase, tyrosinase-related protein-1 (TRP-1), and TRP-29;17;18. As the key enzyme of melanogenesis, mutations with loss of tyrosinase function usually result in albinism, the complete loss of pigmentation19. Mutations of TRP-1 and TRP-2, however, induce alterations of pigment such as color changes rather than complete loss indicating their role as modifiers of melanin composition9;19;20. Controversy about its enzymatic function is reflected by several names which previously had been assigned to TRP-2 but it was finally renamed dopachrome-tautomerase (HGNC symbol: DCT), which describes its function more accurately9–11;21. In spite of its biological role, little attention was paid to TRP-2 considering the extensive expression analysis, which is available for other melanocyte differentiation antigens such as gp100 and Melan-A. Previous studies focused on singular aspects of TRP-2 such as its presence in melanocyte in skin of different ethnicities, in hair follicles, or the impact of UV radiation on TRP-2 expression22–24. Two of the studies were done on cryosections rather than on archival paraffin material22;24. Only one previous report assessed the presence of TRP-2 in a selected number of archival pigmented lesions14. All previous analyses used solely polyclonal reagents, which were rabbit derived and provided by a collaborating lab or a commercially available goat reagent14;22–24. Another study addressed the expression of TRP-2 by in situ hybridization25. Consequently, we initiated our present study by trying to identify a commercial reagent, which would be widely available. We focused on monoclonal reagents due to their superior specificity though their use is often hampered by poor reactivity in archival material. After identifying mAb C-9 as a potentially suitable reagent for immunohistochemistry and based on our experience with many commercial reagents, we initiated our study with a specificity analysis. C-9 showed specific reactivity with TRP-2 in ELISA analyses. Due to our interest in a reagent suitable for immunohistochemistry we also performed a combined histological and molecular analysis of cell lines which demonstrated a congruent presence of TRP-2 mRNA as well as protein as detected by mAb C-9. For melanocyte differentiation antigens, previous data showed a good correlation between mRNA and protein expression as measured by newly generated monoclonal antibodies. This is illustrated by the generation of serological reagents such as mAb T311 to tyrosinase and mAbs A103 or M2-7C10 to Melan-A/MART-1, which revealed high congruency between molecular and immunohistochemical data15;16;26–28. Interestingly, one of the few previous immunohistochemical studies of TRP-2 employing a polyclonal reagent revealed discrepancies between mRNA and protein expression for TRP-2 unlike Melan-A/MART-1, which was analyzed in the same study14. Diminished specificity is the inherent trade-off for good sensitivity for polyclonal reagents and polyclonal reagents to TRP-2 appear to be no exception. We completed our initial analysis with a blocking experiment in the setting of an immunohistochemical stain in which a preparation of TRP-2 protein was able to completely abolish C-9 immunoreactivity.

After determining the specificity of mAb C-9, we continued the study with analyzing the presence of TRP-2 in normal tissues, as well as in various melanocytic and non-melanocytic lesions. In normal tissues, there was no major reactivity except occasionally in granules of hepatocytes and macrophages. Granular staining was also present in melanophages, which is seen with other melanocyte markers as well29. Awareness of the possible granular labeling of macrophages should be sufficient to prevent false interpretation of C-9-immunoreactivity. In normal skin, there was a consistent labeling of melanocytes as previously described with a polyclonal reagent22. In acquired nevi, TRP-2 was expression was similar to tyrosinase and Melan-A with immunopositivity of the junctional as well as dermal cells30;31. No major decrease in immunoreactivity was present in the dermal component, as seen with tyrosinase27;30;32–34. Though nevi were previously analyzed with other non-commercial polyclonal reagents, no exact description of the TRP-2 presence in nevocytes was given14;23. In primary cutaneous melanoma, the high percentage (84%) of TRP-2 positive lesions is comparable to the expression of Melan-A, tyrosinase, or gp10027;30;32–34. In spite of the comparable expression in primary lesions, in metastatic melanoma presence of TRP-2 was only found in little more than half of the cases of our study. Several studies have demonstrated that other melanocyte differentiation antigens such as Melan-A, tyrosinase and gp100 are present in 80–90% of metastatic melanomas16;27;34;35. Moreover, the present series demonstrated that more than half of the immunopositive lesions showed a heterogeneous TRP-2 expression with less than 50% of tumor cells being C-9-positive. The heterogeneous expression of TRP-2 in metastatic lesion may have important implications as to its potential value as a vaccine target for melanoma immunotherapy. In metastatic melanoma, Melan-A, gp100 and tyrosinase usually display homogeneous antigen expression in a majority of lesions34–36. These antigens have been used as targets in various clinical trials and their homogeneous presence is usually considered a therapeutic advantage in immunotherapy37–39. In spite of its heterogeneous expression pattern, TRP-2 was shown to elicit autologous T-cell reponses in melanoma patients and is considered a potential vaccine target40.

The change of trp-2 expression pattern in primary versus metastatic sites may be due to the modification of the tumor antigen profile based on the patient’s autologous immune response, a process referred to as tumor immune-editing’. It was shown that cancer immuoediting can impact and modify the tumor antigen expression profile differently in primary versus metastasis41;42.

The high incidence and homogeneity of TRP-2 expression in primary lesions is also present in mucosal melanomas of the anorectal area and resembles the presence of other melanocyte differentiation antigens43;44. Our study included a limited number of desmoplastic melanomas, which can be diagnostically challenging due to their poor expression of melanocyte differentiation antigens27;30;45;46. Unfortunately but not unsurprisingly, C-9 did not show any reactivity in this type of tumor. This supports the notion that the biology of desmoplastic melanomas vastly differs from common cutaneous epitheloid melanomas and indicating that C-9 will not be of diagnostic value in this type of neoplasm47. Poor reactivity of C-9 was also observed in angiomyolipomas where only two of nine lesions displayed a solely very restricted immunopositivity. Melanocyte differentiation antigens show a peculiar expression pattern in angiomyolipomas/PEComas with a predominance of Melan-A and gp100 and consequently, mAbs HMB-45 and A103 have become key tools for their diagnosis. Tyrosinase is usually poorly expressed in this type of lesion and TRP-2 appears to follow this expression pattern in the present series. Our data support the concept that angiomyolipomas regularly contain structural melanosomal proteins but little or no enzymes of melanogenesis. A variety of other solid tumors such as breast and colon carcinoma were negative for mAb C-9.

In conclusion, in the present study we identified mAb C-9, a commercial reagent, which is applicable for the analysis of the expression of TRP-2 in archival material. We demonstrate a high incidence of TRP-2 in primary cutaneous and mucosal melanomas and a lower incidence in metastatic melanoma. Like other melanocyte differentiation antigens, TRP-2 is negative in desmoplastic melanomas. There is little expression in angiomyolipoma. Our study indicates that mAb C-9 is a specific marker for the detection of TRP-2 in surgical pathology or as a typing reagent in potential future clinical trials employing TRP-2.

Acknowledgments

Financial support and funding: no outside financial support or funding.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest!

Reference List

- 1.Chi A, Valencia JC, Hu ZZ, et al. Proteomic and bioinformatic characterization of the biogenesis and function of melanosomes. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:3135–44. doi: 10.1021/pr060363j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boon T, Old LJ. Cancer Tumor antigens. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:681–3. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busam KJ, Jungbluth AA. Melan-A, a new melanocytic differentiation marker. Adv Anat Pathol. 1999;6:12–8. doi: 10.1097/00125480-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jungbluth AA. Serological reagents for the immunohistochemical analysis of melanoma metastases in sentinel lymph nodes. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2008;25:120–5. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaziji H, Gown AM. Immunohistochemical markers of melanocytic tumors. Int J Surg Pathol. 2003;11:11–5. doi: 10.1177/106689690301100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jager E, Ringhoffer M, Altmannsberger M, et al. Immunoselection in vivo: independent loss of MHC class I and melanocyte differentiation antigen expression in metastatic melanoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:142–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970410)71:2<142::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minor DR. gp100 peptide vaccine in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:771. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1107536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avogadri F, Wolchok JD. Selecting antigens for cancer vaccines. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:328–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchard B, del M V, Jackson IJ, et al. Molecular characterization of a human tyrosinase-related-protein-2 cDNA. Patterns of expression in melanocytic cells. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:127–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassady JL, Sturm RA. Sequence of the human dopachrome tautomerase-encoding TRP-2 cDNA. Gene. 1994;143:295–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsukamoto K, Jackson IJ, Urabe K, et al. A second tyrosinase-related protein, TRP-2, is a melanogenic enzyme termed DOPAchrome tautomerase. EMBO J. 1992;11:519–26. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avogadri F, Merghoub T, Maughan MF, et al. Alphavirus replicon particles expressing TRP-2 provide potent therapeutic effect on melanoma through activation of humoral and cellular immunity. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lupetti R, Pisarra P, Verrecchia A, et al. Translation of a retained intron in tyrosinase-related protein (TRP) 2 mRNA generates a new cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)-defined and shared human melanoma antigen not expressed in normal cells of the melanocytic lineage. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1005–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itakura E, Huang RR, Wen DR, et al. RT in situ PCR detection of MART-1 and TRP-2 mRNA in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues of melanoma and nevi. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:326–33. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen YT, Stockert E, Jungbluth A, et al. Serological analysis of Melan-A(MART-1), a melanocyte-specific protein homogeneously expressed in human melanomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5915–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jungbluth AA, Busam KJ, Gerald WL, et al. A103: An anti-melan-a monoclonal antibody for the detection of malignant melanoma in paraffin-embedded tissues. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:595–602. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson IJ, Chambers DM, Tsukamoto K, et al. A second tyrosinase-related protein, TRP-2, maps to and is mutated at the mouse slaty locus. EMBO J. 1992;11:527–35. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson IJ. A cDNA encoding tyrosinase-related protein maps to the brown locus in mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:4392–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.del Marmol V, Beermann F. Tyrosinase and related proteins in mammalian pigmentation. FEBS Lett. 1996;381:165–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson IJ. Evolution and expression of tyrosinase-related proteins. Pigment Cell Res. 1994;7:241–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1994.tb00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aroca P, Garcia-Borron JC, Solano F, et al. Regulation of mammalian melanogenesis. I: Partial purification and characterization of a dopachrome converting factor: dopachrome tautomerase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1035:266–75. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(90)90088-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Commo S, Gaillard O, Thibaut S, et al. Absence of TRP-2 in melanogenic melanocytes of human hair. Pigment Cell Res. 2004;17:488–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu S, Slominski A, Yang SE, et al. The correlation of TRPM1 (Melastatin) mRNA expression with microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) and other melanogenesis-related proteins in normal and pathological skin, hair follicles and melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(Suppl 1):26–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tobin D, Quinn AG, Ito S, et al. The presence of tyrosinase and related proteins in human epidermis and their relationship to melanin type. Pigment Cell Res. 1994;7:204–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1994.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashimoto Y, Ito Y, Kato T, et al. Expression profiles of melanogenesis-related genes and proteins in acquired melanocytic nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:207–15. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YT, Stockert E, Tsang S, et al. Immunophenotyping of melanomas for tyrosinase: implications for vaccine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8125–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jungbluth AA, Iversen K, Coplan K, et al. T311–an anti-tyrosinase monoclonal antibody for the detection of melanocytic lesions in paraffin embedded tissues. Pathol Res Pract. 2000;196:235–42. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(00)80072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawakami Y, Battles JK, Kobayashi T, et al. Production of recombinant MART-1 proteins and specific antiMART-1 polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies: use in the characterization of the human melanoma antigen MART-1. J Immunol Methods. 1997;202:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahmood MN, Lee MW, Linden MD, et al. Diagnostic value of HMB-45 and anti-Melan A staining of sentinel lymph nodes with isolated positive cells. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:1288–93. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000037313.33138.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Busam KJ, Chen YT, Old LJ, et al. Expression of melan-A (MART1) in benign melanocytic nevi and primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:976–82. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199808000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Busam KJ, Kucukgol D, Sato E, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of novel monoclonal antibody PNL2 and comparison with other melanocyte differentiation markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:400–6. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000152137.81771.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colombari R, Bonetti F, Zamboni G, et al. Distribution of melanoma specific antibody (HMB-45) in benign and malignant melanocytic tumours. An immunohistochemical study on paraffin sections. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1988;413:17–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00844277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gown AM, Vogel AM, Hoak D, et al. Monoclonal antibodies specific for melanocytic tumors distinguish subpopulations of melanocytes. Am J Pathol. 1986;123:195–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaufmann O, Koch S, Burghardt J, et al. Tyrosinase, melan-A, and KBA62 as markers for the immunohistochemical identification of metastatic amelanotic melanomas on paraffin sections. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:740–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrow C, Browning J, MacGregor D, et al. Tumor antigen expression in melanoma varies according to antigen and stage. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:764–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kucher C, Zhang PJ, Acs G, et al. Can Melan-A replace S-100 and HMB-45 in the evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes from patients with malignant melanoma? Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2006;14:324–7. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jager D, Jager E, Knuth A. Vaccination for malignant melanoma: recent developments. Oncology. 2001;60:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000055289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawakami Y, Robbins PF, Wang RF, et al. The use of melanosomal proteins in the immunotherapy of melanoma. J Immunother. 1998;21:237–46. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klein O, Schmidt C, Knights A, et al. Melanoma vaccines: developments over the past 10 years. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10:853–73. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khong HT, Rosenberg SA. Pre-existing immunity to tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-2, a new TRP-2 isoform, and the NY-ESO-1 melanoma antigen in a patient with a dramatic response to immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2002;168:951–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, et al. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:991–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helmke BM, Otto HF. Anorectal melanoma. A rare and highly malignant tumor entity of the anal canal. Pathologe. 2004;25:171–7. doi: 10.1007/s00292-003-0640-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heyn J, Placzek M, Ozimek A, et al. Malignant melanoma of the anal region. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:603–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim E, Browning J, MacGregor D, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: comparison of expression of differentiation antigens and cancer testis antigens. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:347–55. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000222588.22493.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kucher C, Zhang PJ, Pasha T, et al. Expression of Melan-A and Ki-67 in desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic nevi. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:452–7. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200412000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Busam KJ, Zhao H, Coit DG, et al. Distinction of desmoplastic melanoma from non-desmoplastic melanoma by gene expression profiling. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:412–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]