Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To determine whether acute hospitalization is associated with a change in potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use and whether use varies across geographic region.

DESIGN

Observational.

SETTING

Continental United States.

PARTICIPANTS

Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during 2007–08.

MEASUREMENTS

Potentially inappropriate medication use was defined according to the High-Risk Medications in Elderly Adults quality indicator from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set. Prevalence of outpatient PIM use was determined at admission and discharge and then used to identify medications discontinued during hospitalization and incident medications started during this period.

RESULTS

Of 124,051 older adults hospitalized for AMI, 9,607 (7.7%) were outpatient PIM users at admission, which increased to 8.6% at discharge (P < .001). Admission PIM rates varied according to geographic region, as did the effect of hospitalization. Admission PIM use was lowest in the northeast and remained unchanged during hospitalization (5.1–5.1%, P = .95). In contrast, admission PIM use was highest in the south and increased significantly during hospitalization (9.9–11.4%, P < .001). PIM use also increased from the long-term perspective, with 6-month period prevalence rates of 22.6% before admission and 24.6% after discharge (P < .001).

CONCLUSION

Despite intervention studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in PIM use during acute hospitalization, a significant increase in PIM use was observed in a naturalistic setting in Medicare beneficiaries with AMI. Further research is needed to develop an approach to minimizing PIM use in the inpatient setting that is cost-effective and suitable for widespread implementation.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measures, Medicare, potentially inappropriate prescribing, quality of care

Inappropriate prescribing is a major healthcare concern for older adults, with an estimated cost of $7.2 billion annually.1,2 Elderly adults have seven times the risk of hospitalization due to adverse drug events as younger adults, which is largely attributable to more-complex medication regimens and age-related physiological changes affecting drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.1,3,4 In addition, inappropriate prescribing in older adults is specifically associated with twice the risk of adverse health outcomes, including hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and death.5 A common approach to measuring inappropriate prescribing in older adults is the use of explicit criteria sets created by consensus panels. These criteria usually consist of a list of prescribing practices whose risks typically outweigh their benefits in elderly adults.6 Because there may be individual situations in which use is justified, the medications included on these lists are often referred to as potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs). Approximately one in five community-dwelling older adults are exposed to PIMs, with estimates as high as 38.5% in individual studies.7

Hospitalization for an acute medical condition is an important event in the course of chronic illness and may have a significant effect on the trajectory of outpatient PIM use. From one perspective, PIM prescribing may be reduced because inpatient providers have the opportunity to perform a comprehensive peer review of the individual’s drug regimen and discontinue unnecessary or unsafe medications. Conversely, acute hospitalization may increase PIM prescribing because of the presence of multiple prescribers, medication reconciliation problems, and a lack of care coordination among inpatient providers or in the transition back to outpatient care.6 Existing studies have yielded mixed findings as to whether acute hospitalization has a positive or negative effect on the short- or long-term course of outpatient PIM use, and this question has not been explored nationally in Medicare beneficiaries.8–13 Examination of nationally representative data also affords the opportunity to characterize geographic variation in PIM use. Prior analyses of outpatient Medicare beneficiaries demonstrated significant regional variation in PIM prevalence, with the lowest prevalence in the northeast and highest prevalence in the south.14 Similar regional patterns in PIM use have been observed in Veterans Health Administration outpatients and in a national sample of hospitalized elderly adults.10,15 Because PIM use is an indicator of healthcare quality, the consistency of geographic prescribing patterns between these different healthcare systems suggests that individuals living in different regions of the country are exposed to varying levels of quality. There may then be an opportunity for targeted interventions to improve healthcare quality in areas of high PIM prescribing, but no studies have examined geographic variation in outpatient PIM use at the time of acute hospitalization or the effect of hospitalization on PIM use.

To fill these important knowledge gaps, two primary study objectives were developed. The first was to assess the effect of acute hospitalization on the short- and long-term course of outpatient PIM use, and the second was to characterize geographic variation in PIM use at the time of admission and new use associated with hospitalization.

METHODS

Data Sources

The data came from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Chronic Condition Warehouse (CCW) and covered 100% of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in 2007 or 2008. Individuals hospitalized for AMI were chosen as the target population for several reasons. First, it was important to choose a single diagnosis to avoid confounding due to variation in PIM use across diagnostic populations.10 Second, it was necessary to choose a disease that was a common cause of hospitalization16 and associated with high PIM use in relation to other disease states;10 of elderly adults admitted with seven common primary diagnoses, including pneumonia, heart failure, and ischemic stroke, PIM use was highest in those with AMI.10 Last, individuals with severe cardiovascular disease as a result of AMI may be more susceptible to the adverse cardiovascular effects associated with some PIMs.17

The CCW definition of AMI as an inpatient stay with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code 410.xx, (excluding 410.x2) in the first or second diagnosis position of the claim was used.18 Information on enrollment, medical claim files, and Medicare Part D prescription drug events were obtained for each beneficiary. The acute hospital admission date for each AMI served as the index admission date for the AMI. The hospital discharge date was calculated by combining all Medicare institutional claims (acute, long-term care hospital, inpatient rehabilitation facility, critical-access hospital, skilled nursing facility) with overlapping admission and discharge dates after the initial acute hospital admission with an AMI diagnosis.19 Thus, the hospital discharge date reflects when the individual returned home after their AMI, providing a consistent and observable period to measure post-discharge prescribing.

Participant Selection

From the 100% AMI sample, individuals were excluded from the analysis if they did not survive the AMI institutional stay, they had had an AMI 12 months before the index admission date, they were younger than 66 at the index admission date (to ensure Medicare eligibility in the prior year), they were not continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, and D (through a standalone Part D plan) during the 12 months before the index date and for the duration of the follow-up period (until death or a maximum of 12 months after the index discharge date), or they did not reside within the lower 48 states. To ensure adequate follow-up to observe changes in PIM use after discharge, individuals who used hospice or were readmitted to inpatient care, admitted from home to a skilled nursing facility, or died within 30 days after discharge were also excluded. Medication use cannot be characterized during inpatient hospital admissions or postacute skilled nursing care (for up to 100 days after discharge), because Medicare Part A, which does not provide itemized billing information for individual medications, covers these services.

Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use

Several sets of criteria are available to define PIM use.20–23 High-Risk Medications in Elderly Adults (HRME), which the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) has incorporated into its Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), was selected for this analysis. 24 HEDIS contains standardized quality measures that healthcare systems commonly collect for internal quality improvement activities and public reporting, with some evidence that it produces system-level improvements in healthcare quality.25 For these reasons, the HEDIS criteria are arguably the most relevant for studies of healthcare quality and policy. The HRME quality indicator is based principally on published consensus criteria for PIM use in older adults.26 HEDIS national drug code lists from 2011 were used because this version was the closest to the study timeframe that was publically available.

Potentially inappropriate medication use was determined during several time frames and included measures concerned with characterizing short- and long-term changes. Short-term changes in PIM use were characterized using four measures: active at admission, discontinued during hospitalization, new start during hospitalization, and active at discharge. PIMs were considered active at the time of admission according to the presence of a preadmission prescription with a fill date plus days supply that extended to or beyond the hospital admission date. Of medications considered active at admission, those that had no observed fill during the 180 days after discharge were considered discontinued during hospitalization. A new PIM start during hospitalization was defined as an outpatient medication filled within 7 days after hospital discharge but at no point during the 180 days before hospital admission. PIMs considered active at discharge included all PIMs active at admission that were not discontinued and all new PIMs started during the hospitalization. Long-term changes in PIM use were characterized by comparing preadmission prevalence with prevalence after discharge. Period prevalence rates were calculated based on the presence of at least one PIM fill dispensed during the 6 months before AMI hospital admission and separately for the 6 months after discharge. Usage rates were also reported individually for the 10 PIMs most commonly active at the time of AMI hospital admission.

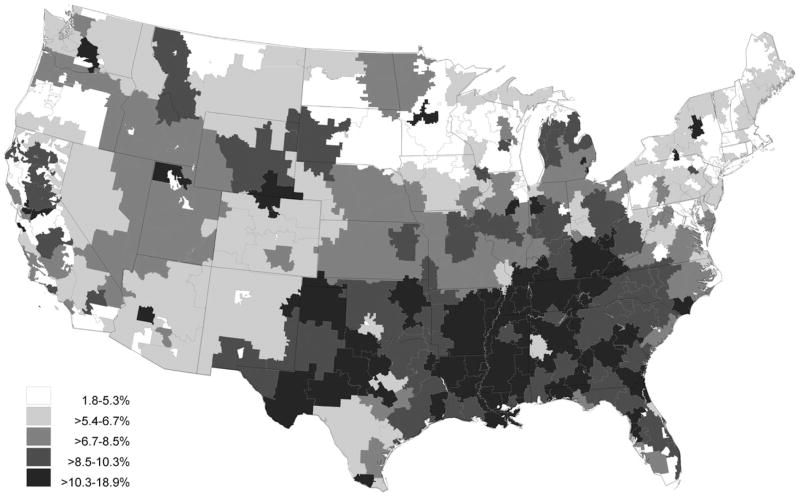

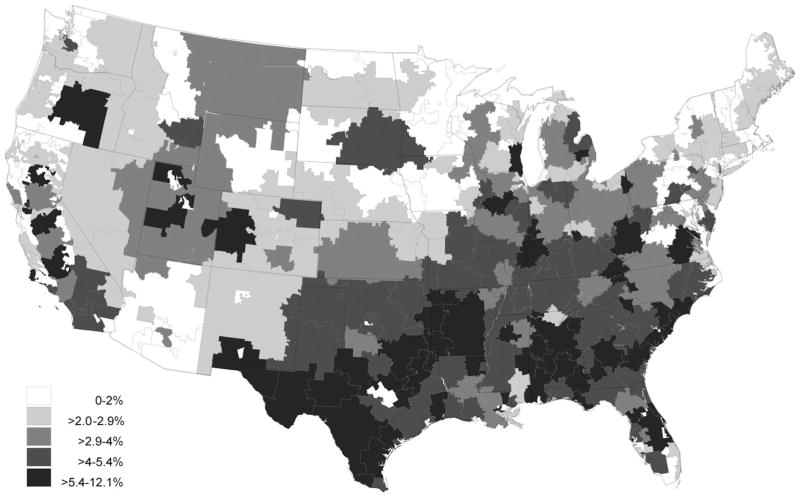

Analysis

Geographic variation was examined at the level of U.S. census region27 and hospital referral region. Hospital referral regions are representations of regional healthcare markets that the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care project defines and are based on referral patterns for major cardiovascular surgical procedures and neurosurgery.28 Consistent with prior analyses, hospital referral regions were used to create geographical maps of PIM frequencies grouped in quintiles and overlaid on U.S. state boundaries. 14 Comparisons of PIM prescribing frequency across geographic regions were conducted using the chi-square test, and frequency changes between exposure periods were compared using the McNemar test for paired frequency data. A post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding propoxyphene, because it accounted for more than 25% of PIM use, and inspection of the data suggested that propoxyphene prescribing had a significant influence on the overall results. A second post hoc analysis was conducted for a subgroup of drugs other than propoxyphene for which cardiovascular adverse events were considered a principal reason for their PIM classification. 29 These drugs included desiccated thyroid, dipyridamole (immediate release), ketorolac, methyl testosterone, nifedipine (immediate release), and thioridazine. This analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which these PIMs were discontinued, given that the narrowest focus of treatment in individuals hospitalized for AMI is on cardiovascular health. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), and all statistical tests were two-tailed at the .05 level of significance.

RESULTS

Patients

The demographic characteristics of the 124,051 older adults hospitalized for AMI who met all selection criteria are summarized in Table 1; 83.2% were white, 69.0% lived in urban areas, and 57.3% were female. All age groups were well represented, including 25,502 (20.6%) aged 85 and older.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics (N = 124,051)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 66–70 | 25,275 (20.4) |

| 71–75 | 24,728 (19.9) |

| 76–80 | 25,418 (20.5) |

| 81–85 | 23,128 (18.6) |

| >85 | 25,502 (20.6) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 71,041 (57.3) |

| Male | 53,010 (42.7) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| White | 103,169 (83.2) |

| Black | 9,734 (7.9) |

| Hispanic | 7,335 (5.9) |

| Asian | 2,372 (1.9) |

| Other | 1,236 (1.0) |

| Unknown | 205 (0.2) |

| Residence according to Rural-Urban Commuting Area code | |

| Metropolitan area | 85,604 (69.0) |

| Nonmetropolitan area | 38,381 (30.9) |

| Unknown | 66 (<0.1) |

Effect of Hospitalization on PIM Use

The effect of hospitalization on the frequency of any PIM use was characterized in the short term immediately surrounding hospitalization and the longer-term of 6 months before and after hospitalization (Table 2). At the time of hospital admission, 9,607 (7.7%) subjects had active PIM medications. Of these, 3,682 did not refill their PIM in the 6 months after discharge and were considered to have discontinued the medication during the period of hospitalization, but 4,666 had a new PIM dispensed within 1 week after discharge and were considered new PIM starters. This net increase from 9,607 (7.7%) to 10,654 (8.6%) PIM users represented a 10.9% increase in PIM use associated within the short-term time frame surrounding hospitalization and was statistically significant (McNemar S = 145, degrees of freedom (df) = 1, P < .001). A similar magnitude of change (8.7%) was observed for the long-term time frame, with the 6-month prevalence increasing from 22.6% before hospitalization to 24.6% after discharge (McNemar S = 214, df = 1, P < .001).

Table 2.

Changes in Potentially Inappropriate Medication (PIM)a Frequency in Older Adults Associated with Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction

| PIM Use | Short-Term Changesa,b

|

Long-Term Changesc

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active at Admission,d n = 124,051 | Active at Discharge,e n = 124,051 | Discontinuation During Hospitalizationf | New Starts During Hospitalization,g n = 124,051 | 6-Month Period Prevalence Before Admission, n = 124,051 | 6-Month Period Prevalence After Discharge, n = 124,051 | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| n (%) | n/N (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Any PIM Use | 9,607 (7.7) | 10,654 (8.6)j | 3,682/9,607 (38.3) | 4,666 (3.8) | 28,097 (22.6) | 30,528 (24.6)j |

|

| ||||||

| Individual PIMsh | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Propoxyphene | 2,622 (2.1) | 4,658 (3.8)j | 722/2,622 (27.5) | 2,758 (2.2) | 10,531 (8.5) | 12,720 (10.3)j |

|

| ||||||

| Conjugated estrogen | 1,281 (1.0) | 958 (0.8)j | 339/1,281 (26.5) | 16 (<0.1) | 1,808 (1.5) | 1,289 (1.0)j |

|

| ||||||

| Nitrofurantoin | 1,074 (0.9) | 1,142 (0.9)k | 486/1,074 (45.3) | 554 (0.4) | 4,244 (3.4) | 5,408 (4.4)j |

|

| ||||||

| Cyclobenzaprine | 883 (0.7) | 655 (0.5)j | 402/883 (45.5) | 174 (0.1) | 3,101 (2.5) | 2,617 (2.1)j |

|

| ||||||

| Hydroxyzine | 786 (0.6) | 718 (0.6)k | 295/786 (37.5) | 227 (0.2) | 2,582 (2.1) | 2,773 (2.2)j |

|

| ||||||

| Promethazine | 621 (0.5) | 700 (0.6)k | 382/621 (61.5) | 461 (0.4) | 3,733 (3.0) | 4,331 (3.5)j |

|

| ||||||

| Belladonna alkaloids | 545 (0.4) | 531 (0.4) | 270/545 (49.5) | 256 (0.2) | 2,789 (2.2) | 2,998 (2.4)k |

|

| ||||||

| Carisoprodol | 402 (0.3) | 331 (0.3)j | 102/402 (25.4) | 31 (<0.1) | 866 (0.7) | 742 (0.6)j |

|

| ||||||

| Dicyclomine | 340 (0.3) | 277 (0.2)j | 119/340 (35.0) | 56 (<0.1) | 1,008 (0.8) | 975 (0.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Desiccated thyroid | 317 (0.3) | 279 (0.2)j | 48/317 (15.1) | 10 (<0.1) | 446 (0.4) | 399 (0.3)j |

|

| ||||||

| Post hoc analyses | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Any PIM use excluding propoxyphene | 7,326 (5.9) | 6,393 (5.2)j | 3,015/7,326 (41.2) | 2,008 (1.6) | 20,693 (16.7) | 21,120 (17.0)k |

|

| ||||||

| PIMs associated with cardiovascular toxicityi | 702 (0.6) | 539 (0.4)j | 248/702 (35.5) | 73 (<0.1) | 1,187 (1.0) | 940 (0.8)k |

PIM use was defined according to the High Risk Medications in the Elderly quality indicator from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set.

Short-term change between active PIM use at admission and at discharge compared using McNemar test for paired frequencies.

Individual columns for any short-term PIM use are not mutually exclusive. For example, a subject could have had an active admission PIM discontinued and a different PIM started during hospitalization. Because of this, the net difference between discharge and admission (10,654–9,607 = 1,047) does not equal the net difference between discontinuations and new starts during hospitalization (4,666–3,682 = 984).

Long-term change between PIM use 6 months before admission and 6 months after discharge compared using McNemar test for paired frequencies.

Defined according to presence of a preadmission prescription with a fill date plus days supply that extended to or beyond the hospital admission date.

Included new medications started during hospitalization and medications that were active at admission but not discontinued during hospitalization.

Defined as a medication that was active at hospital admission but not filled at any time within 180 days after date of hospital discharge.

Defined as a medication filled within 7 days after hospital discharge but at no point within the 180 days before hospital admission.

Ten most frequent PIMs active at the time of hospital admission.

Subgroup of drugs, excluding propoxyphene, for which cardiovascular adverse events were considered a principal reason for their PIM classification, including desiccated thyroid, dipyridamole (immediate release), ketorolac, methyl testosterone, nifedipine (immediate release), and thioridazine.29

P < .001.

P < .05.

Frequencies were also examined individually for the 10 most commonly prescribed PIMs (Table 2). Propoxyphene was the most commonly prescribed PIM in all exposure periods, including active use in 2,622 (2.1%) subjects at the time of hospital admission, 2,758 (2.2%) new starts during hospitalization, and 12,720 (10.3%) subjects in the 6 months after discharge. Other common PIMs at the time of admission were conjugated estrogen (1.0%), nitrofurantoin (0.9%), cyclobenzaprine (0.7%), and hydroxyzine (0.6%). Although the overall trend was toward increasing use, prescribing of some individual PIMs declined significantly in the short- and long-term, including conjugated estrogen, cyclobenzaprine, and carisoprodol.

Two post hoc sensitivity analyses were conducted. When propoxyphene was excluded, short-term PIM use decreased from hospital admission (5.9%) to discharge (5.2%) (Table 2), although PIM use increased over the long term (16.7–17.0%), even when propoxyphene was excluded, demonstrating that any short-term improvement in PIM prescribing was no longer apparent within 6 months after discharge. The second sensitivity analysis examined a subset of drugs with the potential for cardiovascular toxicity (excluding propoxyphene) and found significant short- and long-term decreases in prescribing of these PIMs (Table 2).

Regional Variation in PIM Use

Regional differences in PIM use are shown in Table 3. The prevalence of active PIM use at the time of hospital admission varied significantly according to region (chi-square = 585, df = 3, P < .001) and was lowest in the northeast (5.1%) and highest in the south (9.9%), with comparable intermediate rates in the west (7.0%) and midwest (7.2%). This same regional pattern occurred for PIM rates in all remaining time periods except for discontinuation, during which the opposite trend was observed. The rate of PIM discontinuation during hospitalization was highest in the northeast (43.4%) and lowest in the south (37.2%). The net short-term effect of hospitalization also differed according to region. In the northeast, PIM use remained constant from before admission (5.1%) to after discharge (5.1%) (McNemar S < 0.1, df = 1, P = .95), whereas PIM use increased in the south from 9.9% to 11.4% (McNemar S = 147, df = 1, P < .001). Six-month period prevalence rates increased significantly from before admission to after discharge in all regions, although the magnitude of change reflected the same regional patterns. The number of prevalent PIM users increased from 4,280 to 4,481 in the northeast (McNemar S = 8.5, df = 1, P = .004), an increase of 4.7%. In contrast, PIM users in the south increased from 13,550 before admission to 14,894 after discharge (McNemar S = 145, df = 1, P < .001), an increase of 9.9%. A more-detailed characterization reflecting these regional patterns can be found in Figure 1 for point-prevalent PIM use at admission and in Figure 2 for the incidence of new PIM use during hospitalization. These figures clearly demonstrate that hospital referral regions with the highest levels of prevalent and incident PIM use are highly concentrated in the southern United States.

Table 3.

Regional Variation in Potentially Inappropriate Medication (PIM) Use in Older Adults Hospitalized for Acute Myocardial Infarction

| PIM Exposure Period | National, N = 124,051 | Regional PIM Frequencya | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast, n = 26,340 | West, n = 17,085 | Midwest, n = 32,676 | South, n = 47,950 | ||

| Short-term changesb,c | |||||

| Active at hospital admission,d n (%) | 9,607 (7.7) | 1,341 (5.1) | 1,200 (7.0) | 2,342 (7.2) | 4,724 (9.9) |

| Active at hospital discharge,e n (%) | 10,654 (8.6)i | 1,343 (5.1) | 1,275 (7.5)j | 2,566 (7.9)i | 5,470 (11.4)i |

| Discontinuation during hosptialization,f n/N (%) | 3,682/9,607 (38.3) | 579/1,341 (43.4) | 464/1,200 (38.3) | 880/2,342 (37.9) | 1,759/4,724 (37.2) |

| New start during hospitalization,g n (%) | 4,666 (3.8) | 578 (2.2) | 542 (3.2) | 1,080 (3.3) | 2,466 (5.1) |

| Long-term changesh | |||||

| Before admission, 6-month prevalence, n (%) | 28,097 (22.6) | 4,280 (16.3) | 3,484 (20.4) | 6,783 (20.8) | 13,550 (28.3) |

| After discharge, 6-month prevalence, n (%) | 30,528 (24.6)i | 4,481 (17.0)j | 3,686 (21.6)i | 7,467 (22.9)i | 14,894 (31.1)i |

PIM use was defined according to the High Risk Medications in the Elderly quality indicator from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set.

The difference in PIM frequency across regions was statistically significant across all periods of PIM exposure at P < .001.

Short-term change between active PIM use at admission and discharge compared using McNemar test for paired frequencies.

Individual columns for any short-term PIM use are not mutually exclusive. For example, a subject could have had an active admission PIM discontinued and a different PIM started during hospitalization. Because of this, the net difference between discharge and admission (10,654–9,607 = 1,047) does not equal the net difference between discontinuations and new starts during hospitalization (4,666–3,682 = 984).

Defined according to the presence of a preadmission prescription with a fill date plus days supply that extended to or beyond the hospital admission date.

Included medications started during hospitalization and medications that were active at admission but not discontinued during hospitalization.

Defined as a medication that was active at hospital admission but not filled at any time within 180 days after date of hospital discharge.

Defined as a medication filled within 7 days after hospital discharge but at no point within the 180 days before hospital admission.

Long-term change between PIM use 6 months before admission to 6 months after discharge compared using McNemar test for paired frequencies.

P < .001.

P < .05.

Figure 1.

Prevalence at admission of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction.

Figure 2.

Incidence of new potentially inappropriate medication starts in older adults during hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding was that hospitalization for AMI was associated with a net increase in potentially inappropriate prescribing practices. The number of new PIM starts outpaced discontinuations in the weeks surrounding the hospitalization, producing a short-term increase from 7.7% to 8.6%. Increased PIM use was also evident for the long-term timeframe, with the 6-month period prevalence increasing from 22.6% before admission to 24.6% after discharge, an increase of 8.6%. The effect of hospitalization on PIM use has been mixed in prior studies, in which the primary determinant may have been the setting of care.8,9,11–13,30,31 Two studies involved a specific intervention to target PIM use during hospitalization and demonstrated reductions of approximately 80%.13,30 An additional five studies examined changes in PIM use in a naturalistic setting without a specific research intervention; PIM use decreased during hospitalization in three studies and increased in two. All three studies showing decreased PIM use involved geriatric specialty units,8,9,31 whereas the remaining two studies involved other settings.11,12 In addition, the magnitude of change in these naturalistic studies was smaller than in intervention studies, with increases or decreases of approximately 15% to 30%. Based on this interpretation of the literature, the findings are consistent with existing studies in showing a modest increase in PIM use for individuals hospitalized in a nongeriatric setting and in the absence of any specific intervention program to reduce PIM use.

The second objective of this study was to examine regional variation in PIM use in terms of point prevalence at the time of AMI hospitalization and incident use within 1 week after discharge. Regional differences were the same for both measures, with PIM use lowest in the northeast and approximately twice as high in the south. PIM use in the midwest and west were comparable and fell in the middle of this range. This pattern corroborates existing studies that have been remarkably consistent despite difference in treatment setting, PIM criteria, and time period. Studies involving outpatient Medicare beneficiaries,14 Veterans Health Administration outpatients,15 surgical inpatients, 32 medical inpatients,10 and individuals in the emergency department33 all found the highest PIM rates in the southern United States—nearly twice as high as the lowest regional rate. The regions with lowest PIM use were the northeast in four of five studies10,14,15,33 and the Midwest in the remaining study.32 PIM use is a commonly applied indicator of healthcare quality that serves as a proxy measure for inappropriate prescribing practices of non-PIM medications and, in turn, association with risk of adverse drug events.34,35 Therefore, it is likely that regional variations in PIM use mirror underlying variations in medication safety and healthcare quality. The current analysis extends the existing literature by examining regional variation in the prevalence of outpatient PIM use at the time of hospitalization for a common, acute medical condition and is the first to focus specifically on variation in incident PIM use in any population or setting. Although the majority of the HRME literature has focused on prevalent PIM use, incident PIM use is gaining recognition as often being the more-relevant metric for research design and potentially even for assessing healthcare quality and public policy.36–39

A single drug—propoxyphene—significantly influenced the findings. It was the most commonly prescribed PIM in all exposure periods and accounted for 2,758 of 4,666 (59.1%) new PIM starts during hospitalization. It is likely that propoxyphene prescribing is attributable to legitimate indications for pain management, although safer, more-effective alternatives are available. The potential influence of propoxyphene is particularly noteworthy because the Food and Drug Administration removed it from the U.S. market in 2010. This is especially pertinent to individuals hospitalized for AMI because it was removed based on cardiac-related adverse events, specifically risk of serious or even fatal arrhythmias. When propoxyphene was excluded in post hoc analyses, PIM prescribing had decreased in the short term but increased within 6 months after discharge. It is therefore unclear how the withdrawal of propoxyphene will affect PIM prescribing, but the findings emphasize the important effect that a single policy change, such as the removal of propoxyphene from the U.S. market, can have on clinical practice. With the exception of propoxyphene, prescribing of other PIMs with cardiovascular toxicity decreased by approximately 25%, from 702 (0.6%) subjects to 529 (0.4%), and this change was maintained for at least 6 months after discharge. This finding suggests that PIM discontinuation during hospitalization in a naturalistic setting may be more likely when the medication is directly related to the admitting diagnosis.

This study is subject to important limitations. Medicare Part D files contain only dispensing records for outpatient medications. It is not known what PIMs were dispensed during the inpatient stay, nor was there any documentation concerning the rationale for prescribing decisions. Therefore, it is uncertain whether the inpatient treatment team or outpatient providers made decisions to stop or start PIMs during the time surrounding the acute hospitalization period. The definition of new PIM starts was limited to within 7 days after discharge to minimize the likelihood that outpatient providers started these drugs. Similarly, it is not certain that inpatient providers stopped discontinued medications. It could be that the planned course of treatment before admission was completed during the hospital stay or that the outpatient provider had instructed the individual to discontinue the PIM before admission but before the dispensed supply had run out. In addition, PIM use could not be observed outside prescription fill events observed in Medicare Part D claims, which do not include over-the-counter medications or prescription drugs purchased out of pocket or acquired through other prescription plans (e.g., Medicare Advantage plans, private insurance, Veterans Health Administration). It is therefore also unknown how well the findings can be generalized to individuals who receive prescription drug benefits from these plans or systems. A further limitation with HRME or other similar sets of explicit prescribing criteria is that PIM use, by definition, is “potentially inappropriate.” Although it has been argued that PIM indicators may have insufficient specificity for individual-level analyses,40 they may still serve as valid proxy measures at aggregated levels, such as U.S. Census region.34 As long as the positive predictive value of a PIM criteria set does not vary systematically according to geographic region, variations in potentially inappropriate prescribing practices will mirror underlying variations in actual inappropriate prescribing.

Although broadly understudied, initial clinical reports have demonstrated that PIM use in elderly adults can be up to 80% lower in the inpatient setting when focused clinical interventions are applied,13,30 although the current findings corroborate existing studies in showing that PIM prescribing does not decrease, or may even increase, in the naturalistic, real-word inpatient practice environment. Geriatric specialty units are a potential exception to this rule but do not approach the magnitude of reduction seen in targeted intervention studies.8,9,31 In the context of existing literature, the current findings suggest that hospitalization for an acute medical condition, such as AMI, is currently a missed opportunity to enhance safety by eliminating potentially inappropriate prescribing practices. Existing studies have shown that interdisciplinary care incorporating geriatric specialists, including physicians, pharmacists, and nurses, may be helpful.13,30 Medication reconciliation has also gained increasing attention as a means of enhancing medication safety surrounding inpatient hospitalizations, and these reviews may be a natural place to integrate a program to reduce PIM use.41 Less-intensive interventions such as real-time order entry alerts for high-risk medications have been effective in the outpatient setting and may also prove successful during acute hospitalization.42 Further research is needed to develop an approach to minimizing PIM use in the inpatient setting that is cost-effective and suitable for widespread implementation.

Acknowledgments

Stephen Welch, PhD, and Elizabeth Cook, MS, of the University of Iowa College of Pharmacy provided assistance in producing the tables and figures for this manuscript. They did not receive compensation for their contributions apart from employment at the institution where this study was conducted.

This research was funded by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Grant 1 R01 HSO18381–01A1 under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Dr. Lund received support through Career Development Award 10–017 from the Health Services Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

This work was presented, in part, at the American Pharmacists Association Annual Meeting and Exposition, March 28, 2014, Orlando, Florida.

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Sponsor’s Role: None of the sponsors had any role in the study design, methods, analyses, interpretation, or in preparation of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author Contributions: Lund, Schroeder, and Brooks had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Lund, Schroeder, Middendorff, Brooks. Acquisition of data: Brooks. Analysis and interpretation of data: Lund, Schroeder, Middendorff, Brooks. Drafting of the manuscript: Lund, Schroeder, Middendorff. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Lund, Schroeder, Middendorff, Brooks. Statistical analysis: Lund, Schroeder. Obtained funding: Brooks. Administrative, technical, and material support: Lund, Schroeder, Middendorff. Study supervision: Lund, Schroeder.

References

- 1.O’Connor MN, Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. Inappropriate prescribing: Criteria, detection and prevention. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:437–452. doi: 10.2165/11632610-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu AZ, Jiang JZ, Reeves JH, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use and healthcare expenditures in the US community-dwelling elderly. Med Care. 2007;45:472–476. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254571.05722.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangoni AA, Jackson SHD. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: Basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;57:6–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenbach KN, et al. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296:1858–1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perri M, III, Menon AM, Deshpande AD, et al. Adverse outcomes associated with inappropriate drug use in nursing homes. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:405–411. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page RL, II, Linnebur SA, Bryant LL, et al. Inappropriate prescribing in the hospitalized elderly patient: Defining the problem, evaluation tools, and possible solutions. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:75–87. doi: 10.2147/cia.s9564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opondo D, Eslami S, Visscher S, et al. Inappropriateness of medication prescriptions to elderly patients in the primary care setting: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egger SS, Bachmann A, Hubmann N, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly patients: Comparison between general medical and geriatric wards. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:823–837. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Nouaille Y, et al. Impact of hospitalisation in an acute medical geriatric unit on potentially inappropriate medication use. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:49–59. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Liu F, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in hospitalized elders. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:91–102. doi: 10.1002/jhm.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morandi A, Vasilevskis EE, Pandharipande PP, et al. Inappropriate medications in elderly ICU survivors: Where to intervene? Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1032–1034. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakken MS, Ranhoff AH, Engeland A, et al. Inappropriate prescribing for older people admitted to an intermediate-care nursing home unit and hospital wards. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2012;30:169–175. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2012.704813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang PO, Vogt-Ferrier N, Hasso Y, et al. Interdisciplinary geriatric and psychiatric care reduces potentially inappropriate prescribing in the hospital: Interventional study in 150 acutely ill elderly patients with mental and somatic comorbid conditions. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:406.e1–406.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Baicker K, Newhouse JP. Geographic variation in the quality of prescribing. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1985–1988. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund BC, Charlton ME, Steinman MA, et al. Regional differences in prescribing quality among elder veterans and the impact of rural residence. J Rural Health. 2013;29:172–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Traynor K. Close vote by FDA advisers favors propoxyphene withdrawal. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:518–520. doi: 10.2146/news090024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiyota Y, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, et al. Accuracy of Medicare claims-based diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction: Estimating positive predictive value on the basis of review of hospital records. Am Heart J. 2004;148:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook EA, Schneider KM, Chrischilles E, et al. Accounting for unobservable exposure time bias when using Medicare prescription drug data. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3:E1–E18. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.04.a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhan C, Sangl J, Bierman AS, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in the community-dwelling elderly: Findings from the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. JAMA. 2001;286:2823–2829. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrank WH, Polinski JM, Avorn J. Quality indicators for medication use in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:S373–S382. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallagher PF, Barry PJ, Ryan C, et al. Inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of elderly patients as determined by Beers’ criteria. Age Ageing. 2008;37:96–101. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fick DM, Semla TP. 2012 American Geriatrics Society Beers criteria: New year, new criteria, new perspective. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:614–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Quality Assurance. [Accessed January 22, 2013];HEDIS 2011 NDC Lists [on-line] Available at http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement/HEDISMeasures/HEDIS2011/HEDIS2011NDCLicense/HEDIS2011FinalNDCLists.aspx.

- 25.Jung K. The impact of information disclosure on quality of care in HMO markets. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:461–468. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, et al. Updating the Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults: Results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2716–2724. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed September 5, 2013];Census Regions and Divisions of the United States [on-line] Available at http://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/maps/pdfs/reference/us_regdiv.pdf.

- 28.Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. [Accessed January 17, 2014];The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care [on-line] Available at www.dartmouthatlas.org.

- 29.American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown BK, Earnhart J. Pharmacists and their effectiveness in ensuring the appropriateness of the chronic medication regimens of geriatric inpatients. Consult Pharm. 2004;19:432–436. doi: 10.4140/tcp.n.2004.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onatade R, Auyeung V, Scutt G, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in patients on admission and discharge from an older peoples’ unit of an acute UK hospital. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:729–737. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finlayson E, Maselli J, Steinman MA, et al. Inappropriate medication use in older adults undergoing surgery: A national study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2139–2144. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meurer WJ, Potti TA, Kerber KA, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication utilization in the emergency department visits by older adults: Analysis from a nationally representative sample. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:231–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lund BC, Steinman MA, Chrischilles EA, et al. Beers criteria as a proxy for inappropriate prescribing of other medications among older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:1363–1370. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lund BC, Carnahan RM, Egge JA, et al. Inappropriate prescribing predicts adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:957–963. doi: 10.1345/aph.1m657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: New-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gellad WF, Good CB, Amuan ME, et al. Facility-level variation in potentially inappropriate prescribing for older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1222–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson ES, Bartman BA, Briesacher BA, et al. The incident user design in comparative effectiveness research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:1–6. doi: 10.1002/pds.3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pugh MJ, Marcum ZA, Copeland LA, et al. The quality of quality measures: HEDIS(R) quality measures for medication management in the elderly and outcomes associated with new exposure. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:645–654. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0086-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinman MA, Rosenthal GE, Landefeld CS, et al. Agreement between drugs-to-avoid criteria and expert assessments of problematic prescribing. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1326–1332. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, et al. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1057–1069. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zillich AJ, Shay K, Hyduke B, et al. Quality improvement toward decreasing high-risk medications for older veteran outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1299–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]