Abstract

Patterning of the Drosophila embryonic termini by the Torso (Tor) receptor pathway has long served as a valuable paradigm for understanding how receptor tyrosine kinase signaling is controlled. However, the mechanisms that underpin the control of Tor signaling remain to be fully understood. In particular, it is unclear how the Perforin-like protein Torso-like (Tsl) localizes Tor activity to the embryonic termini. To shed light on this, together with other aspects of Tor pathway function, we conducted a genome-wide screen to identify new pathway components that operate downstream of Tsl. Using a set of molecularly defined chromosomal deficiencies, we screened for suppressors of ligand-dependent Tor signaling induced by unrestricted Tsl expression. This approach yielded 59 genomic suppressor regions, 11 of which we mapped to the causative gene, and a further 29 that were mapped to <15 genes. Of the identified genes, six represent previously unknown regulators of embryonic Tor signaling. These include twins (tws), which encodes an integral subunit of the protein phosphatase 2A complex, and α-tubulin at 84B (αTub84B), a major constituent of the microtubule network, suggesting that these may play an important part in terminal patterning. Together, these data comprise a valuable resource for the discovery of new Tor pathway components. Many of these may also be required for other roles of Tor in development, such as in the larval prothoracic gland where Tor signaling controls the initiation of metamorphosis.

Keywords: Drosophila, cell signaling, embryo, receptor tyrosine kinase, terminal patterning, Torso, Torso-like, Mutant screen report

The first events that define the major axes and termini of the early Drosophila embryo are governed by genes expressed in the mother (St Johnston and Nüsslein-Volhard 1992). Patterning of the termini is achieved by spatially localized activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) Torso (Tor) and signal transduction via the highly conserved Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade. This pathway leads to the transcriptional derepression of key zygotic target genes including tailless (tll) and huckebein (hkb) to drive terminal cell fate specification (Brönner and Jäckle 1991). Since its discovery, the Tor pathway/terminal patterning system has been a valuable paradigm for understanding fundamental aspects of how RTK signaling is controlled in space and time [for a review, see Li (2005)].

Despite much interest, however, several key features of the terminal patterning system remain unclear. These include the mechanism by which Tor is activated by its ligand Trunk (Trk) only at the ends of the embryo. A significant body of work suggests that Tor activation is controlled by Torso-like (Tsl), a protein localized to the early embryo termini (Savant-Bhonsale and Montell 1993; Martin et al. 1994). For example, Tor signaling is not activated in the absence of Tsl (Sprenger et al. 1993), and unrestricted expression of Tsl induces ubiquitous Tor signaling (Savant-Bhonsale and Montell 1993; Martin et al. 1994).

Tsl is a member of the perforin-like superfamily of proteins best characterized in terms of their membrane pore-forming roles in vertebrate immune defense (Rosado et al. 2008; Law et al. 2010; Dudkina et al. 2016). Current hypotheses for Tsl function include: the control of Trk proteolysis and activation (Casanova et al. 1995; Casali and Casanova 2001), Trk secretion (Johnson et al. 2015), and facilitation of Tor dimerization or the binding of Trk to Tor (Amarnath et al. 2017). For each of these possibilities, it is highly likely that additional pathway components remain undiscovered; their identification could provide valuable insights into the mechanism controlling localized Tor activation.

A number of screening approaches have previously been used to identify genes involved in terminal patterning. The terminal class genes were first discovered in early mutagenesis screens that identified many components of the major developmental pathways required for embryonic patterning (Schupbach and Wieschaus 1986, 1989; Nusslein-Volhard et al. 1987). However, a major limitation of this approach was that the maternal effect of a given allele could only be examined if homozygous mothers were viable. Zygotic lethal maternal effect screens and dominant modifier screens have been used to overcome this problem (Strecker et al. 1991; Perrimon et al. 1996; Bellotto et al. 2002; Li and Li 2003; Luschnig et al. 2004). Unlike the saturating whole-genome mutant screens, however, zygotic lethal screens are low-throughput and hence were performed on a smaller scale. Furthermore, this approach precludes the detection of genes that perform critical roles during oogenesis and prior to pattern formation. By contrast, dominant modifier screens are not limited in this regard and have been successfully performed using the phenotype produced by tor gain-of-function alleles to find new genes that act downstream of Tor (Strecker et al. 1991; Li and Li 2003). However, use of these alleles does not permit the discovery of potential interactors involved in generating the active Tor ligand (i.e., acting upstream of tor).

Since we were interested in the events upstream of Tor, we conducted a genome-wide screen to identify suppressors of the phenotype produced upon ectopic tsl expression. This screen has the ability to identify new pathway components that function either upstream or downstream of tor and led to the identification of six genes that had not previously been associated with embryonic terminal patterning. In addition, we performed detailed mapping for a further 48 genomic suppressor regions that may contain novel regulators of ligand-dependent Tor signaling.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks

The following stocks were used: w1118 (BL5905), P{GawB}c355 (called c355-Gal4, from BL3750), P{tubP-GAL80ts} (from BL7018), UAS-tsl (Johnson et al. 2013), nos-Cas9 (CAS-0001), and P{nos-ΦC31} lines (TBX-0002 and TBX-0003; Kondo and Ueda 2013), and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Centre (BDSC) deficiency kit (Cook et al. 2012). All nonkit deficiency lines used for mapping are listed in Table 2, and alleles tested are given in Supplemental Material, Table S2. All flies were maintained on standard media at 25° unless otherwise stated.

Table 2. Genomic regions that contain suppressors of the ectopic maternal Tsl phenotype.

| Suppressor Region | BDSC Kit Deficiency | Strength of Suppression | Additional Deficiencies Tested | Strength of Suppression | Suppressor Region Coordinates (Estimated) | Number of Genes in Suppressor Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Df(1)svr | +++ | Df(1)ED6396 | +++ | X:493,529–523,630 | CG17896, CG17778, svr, arg, elav |

| Df(1)BSC530 | +++ | |||||

| 2 | Df(1)ED6443 | +++ | Df(1)Exel6223 | +++ | X:769,982–841,105 | 8 |

| Df(1)BSC534 | n.s. | |||||

| 3 | Df(1)ED411 | ++ | Df(1)ED6579 | ++ | X:2,589,210–2,636,213 | 14 |

| Df(1)ED6584 | n.s. | |||||

| 4 | Df(1)ED6712 | ++ | X:3,432,535–3,789,615 | 24 | ||

| 5 | Df(1)ED6727 | ++ | X:4,325,174–4,911,061 | 56 | ||

| 6 | Df(1)BSC867 | ++ | Df(1)BSC882 | n.s. | X:7,015,408–7,041,515 | CG12541, CG14427 |

| 7 | Df(1)BSC622 | +++ | X:7,908,547–7,955,978 | 11 | ||

| Df(1)C128 | +++ | |||||

| 8 | Df(1)ED7005 | ++++ | Df(1)ED429 | n.s. | X:10,071,922–10,086,426 | CR45602, ZAP3, CG2972, CG2974, RhoU |

| Df(1)BSC822 | ++ | |||||

| Df(1)BSC712 | +++ | |||||

| 9 | Df(1)ED7161 | ++ | Df(1)Exel6244 | n.s. | X:12,007,087–12,750,866 excluding X:12,463,585–12,547,951 | 58 |

| 10 | Df(1)BSC767 | ++ | X:13,278,810–13,591,554 | 39 | ||

| 11a | Df(1)ED7217 | ++ | X:13,642,083–14,653,944 | 111 | ||

| Df(1)ED7225 | ++ | |||||

| Df(1)ED7229 | ++ | |||||

| 12 | Df(1)ED7289 | ++++ | Df(1)BSC310 | n.s. | X:15,089,556–15,125,750 | Rab3-GEF, CG9702, Cyp4s3, drd |

| 13 | Df(1)ED7331 | +++ | Df(1)BSC706 | +++ | X:15,450,255–15,484,792 | 12 |

| 14 | Df(2L)JS31 | +++ | 2L:2,830,265–2,868,633 | 10 | ||

| Df(2L)BSC692 | +++ | |||||

| 15 | Df(2L)BSC295 | ++ | Df(2L)BSC218 | ++ | 2L:4,197,800-Art2 (incl.) | 9 |

| Df(2L)M24F-B | n.s. | |||||

| 16 | Df(2L)ED7853 | + | Df(2L)Exel8013 | ++ | 2L:4,979,299–5,000,943 | CG8892, CG34126, Rtnl1 |

| Df(2L)Exel6010 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(2L)Exel9062 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(2L)Exel8012 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(2L)BSC182 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(2L)BSC811 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(2L)Exel7021 | n.s. | |||||

| 17 | Df(2L)BSC143 | ++++ | Df(2L)Exel7046 | n.s. | 2L:10,260,017–10,276,871 | 8 |

| Df(2L)BSC827 | +++ | |||||

| 18 | Df(2L)BSC812 | ++ | Df(2L)BSC147 | n.s. | 2L:13,800,829–13,819,589 | CAH1, Adat1, CG16865, CG16888, Sos |

| Df(2L)BSC691 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(2L)Exel7059 | ++ | |||||

| 19 | Df(2L)ED793 | ++ | Df(2L)Exel8033 | n.s. | 2L:14,013,641–14,300,969 | 17 |

| Df(2L)Exel6035 | n.s. | |||||

| 20 | Df(2L)Exel8038 | ++ | Df(2L)BSC256 | n.s. | 2L:18,320,008–18,444,727 | 7 |

| Df(2L)BSC149 | n.s. | |||||

| 21 | Df(2L)ED1303 | ++ | Df(2L)Exel7077 | n.s. | 2L:19,753,324–19,918,015 | 47 |

| Df(2L)ED1315 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(2L)BSC258 | n.s. | |||||

| 22 | Df(2R)BSC595 | ++ | 2R:10,462,874–11,197,412 | 76 | ||

| 23 | Df(2R)ED2426 | ++ | Df(2R)Exel7135 | n.s. | 2R:15,262,942–15,373,060 | 12 |

| 24 | Df(2R)BSC355 | ++ | Df(2R)BSC406 | ++ | 2R:17,484,828–17,518,127 | 7 |

| 25 | Df(2R)ED3791 | ++ | 2R:20,870,855–21,215,223 | 69 | ||

| 26 | Df(2R)BSC787 | ++ | Df(2R)BSC598 | n.s. | 2R:22,678,681–22,729,367 | 10 |

| Df(2R)Exel6079 | n.s. | |||||

| 27 | Df(2R)BSC136 | ++ | Df(2R)BSC660 | n.s. | 2R:23,949,444–23,992,124 | 19 |

| Df(2R)BSC770 | ++ | |||||

| Df(2R)BSC601 | ++ | |||||

| 28 | Df(3L)ED50002 | ++ | 3L:1–123,924 | 7 | ||

| 29 | Df(3L)BSC371 | ++ | Df(3L)BSC372 | + | 3L:5,366,062–5,558,677 | 18 |

| Df(3L)Exel6105 | ++ | |||||

| Df(3L)ED210 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3L)BSC387 | n.s. | |||||

| 30 | Df(3L)BSC410 | ++ | Df(3L)BSC438 | ++ | 3L:5,777,085–5,926,648 | 25 |

| Df(3L)BSC411 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3L)Exel7210 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3L)BSC884 | n.s. | |||||

| 31 | Df(3L)BSC816 | ++ | 3L:8,639,081–8,745,326 | 14 | ||

| 32 | Df(3L)BSC113 | ++ | 3L:9,384,075–9,423,491 | 10 | ||

| 33 | Df(3L)ED4457 | ++ | 3L:10,363,951–11,096,989 | 85 | ||

| 34 | Df(3L)ED4502 | ++ | Df(3L)BSC737 | n.s. | 3L:13,346,618–13,417,155 | 14 |

| Df(3L)BSC614 | ++ | |||||

| Df(3L)Exel6119 | n.s. | |||||

| 35 | Df(3L)ED217 | +++ | Df(3L)BSC837 | +++ | 3L:15,098,731–15,151,057 | 18 |

| Df(3L)BSC578 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3L)BSC441 | n.s. | |||||

| 36 | Df(3L)ED4674 | +++ | Df(3L)Exel6130 | ++ | 3L:16,780,123–16,806,648 | CG9706, eIF3e, CG9674 |

| Df(3L)ED4606 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3L)ED4685 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3L)Exel9002 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3L)Exel9003 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3L)Exel9004 | n.s. | |||||

| 37 | Df(3L)ED4710 | +++ | 3L:17,612,170–17,795,144 | 29 | ||

| 38 | Df(3L)ED4858 | ++ | Df(3L)BSC830 | ++ | 3L:19,929,242–20,103,877 | 26 |

| Df(3L)BSC446 | n.s. | |||||

| 39 | Df(3L)BSC223 | +++ | Df(3L)BSC284 | ++ | 3L:21,916,420–21,955,091 | 6 |

| Df(3L)Exel6137 | +++ | |||||

| 40 | Df(3R)BSC633 | ++ | Df(3R)ED7665 | n.s. | 3R:7,080,388–7,090,527 | Ref1, Dpck, Tailor, CR45907, alphaTub84B |

| 41 | Df(3R)ED5339 | ++ | Df(3R)BSC507 | +++ | 3R:9,259,246–9,352,375 | 13 |

| Df(3R)Exel6152 | n.s. | |||||

| 42 | Df(3R)BSC476 | +++ | Df(3R)Exel6153 | ++ | 3R:9,513,020–9,550,705 | 9 |

| 43 | Df(3R)Exel6155 | ++ | 3R:9,928,791–10,089,458 | 12 | ||

| 44 | Df(3R)BSC621 | +++ | 3R:10,111,458–10,144,754 | 8 | ||

| Df(3R)ED5474 | +++ | |||||

| 45 | Df(3R)ED5514 | ++ | 3R:11,200,280–11,230,695 | 12 | ||

| 46 | Df(3R)BSC486 | ++ | Df(3R)Exel8157 | ++ | 3R:13,012,713–13,051,785 | 12 |

| Df(3R)ED5610 | n.s. | |||||

| 47 | Df(3R)ED5664 | ++ | Df(3R)ED10557 | ++ | 3R:14,986,411–15,094,157 | 7 |

| Df(3R)ED10556 | ++ | |||||

| Df(3R)ED10555 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3R)BSC750 | n.s. | |||||

| 48 | Df(3R)Exel7328 | ++ | 3R:16,009,418–16,157,456 | 19 | ||

| 49 | Df(3R)BSC748 | ++ | Df(3R)Exel6176 | n.s. | 3R:16,977,724–17,149,107 | 23 |

| 50 | Df(3R)BSC650 | ++ | Df(3R)Exel6178 | ++ | 3R:18,196,430–18,274,622 | 22 |

| Df(3R)BSC682 | ++ | |||||

| 51 | Df(3R)BSC517 | ++ | Df(3R)BSC141 | n.s. | 3R:20,031,267–20,594,880 | 56 |

| 52 | Df(3R)Exel6272 | ++ | 3R:21,060,603–21,112,334 | 11 | ||

| 53 | Df(3R)ED6085 | ++ | Df(3R)ED6090 | n.s. | 3R:22,026,005–22,042,224 | 8 |

| Df(3R)BSC804 | ++ | |||||

| 54 | Df(3R)BSC619 | ++ | Df(3R)ED6096 | n.s. | 3R:23,258,092–23,279,758 | wda, CG13827, orb |

| Df(3R)BSC803 | n.s. | |||||

| Df(3R)ED6105 | ++ | |||||

| Df(3R)Exel9012 | n.s. | |||||

| 55 | Df(3R)BSC461 | +++ | Df(3R)BSC679 | ++ | 3R:25,092,692–25,137,846 | 15 |

| Df(3R)BSC493 | ++ | |||||

| 56 | Df(3R)BSC501 | ++ | Df(3R)Exel6212 | ++ | 3R:29,215,175–29,288,231 | 15 |

| 57 | Df(3R)BSC620 | ++ | Df(3R)BSC861 | ++ | 3R:29,877,104–29,934,580 | 14 |

| 58 | Df(3R)ED6346 | ++ | 3R:30,794,955–31,011,935 | 20 | ||

| 59 | Df(3R)BSC793 | +++ | 3R:31,311,048–31,458,140 | 14 |

Suppressor strength and the molecular coordinates of the suppressor regions are given when possible. Suppression was scored qualitatively based on segment gain and consistency; weak (+), moderate (++), strong (+++), and very strong (++++). Mapping was conducted using a combination of the BDSC deficiency kit and additional molecularly defined deficiencies. The number of genes within each candidate region is indicated; in cases where there are five or less, the gene symbols are provided. n.s., no suppression was observed.

Region likely contains multiple suppressor loci.

Screening crosses

Autosomal deficiencies or mutant alleles were tested by crossing virgin females from the screen line (c355-Gal4; Gal80ts; UAS-tsl) to deficiency males. X-chromosome deficiencies or mutant alleles were tested by crossing deficiency females to males from the screen line. In all cases, crosses were performed at 22° and cultures shifted to 29° ∼92 hr post egg lay. From each cross, at least 10 F1 females carrying the deficiency chromosome and screening transgenes were placed in a vial containing apple juice agar supplemented with yeast paste and allowed to mate with w1118 males.

Cuticle preparations and scoring

Adults were allowed to lay for 24 hr, and embryos were left to develop for a further 24 hr. Embryos were then dechorionated in 50% (v/v) bleach and mounted on slides in a mixture of 1:1 (v/v) Hoyer’s solution: lactic acid. Slides were incubated overnight at 65° and imaged using dark field optics (Leica). Three consecutive cuticle preps were performed for each deficiency; if suppression was observed, the deficiency was retested at least twice. Suppression strength was qualitatively assessed based on the number of embryos showing central segment gain and the number of segments gained compared with controls (screen line crossed to w1118).

Immunostaining and imaging

Ovaries were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) while on ice and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 hr. Ovaries were then washed five times in PBS with 0.1% Triton-X (PTx) followed by blocking in 5% goat serum in PTx and incubation with anti-Tsl (1:500) overnight at 4°. Anti-Tsl was raised in a rabbit against a peptide consisting of the C-terminal 18 residues of Tsl and affinity purified (Genscript). We note that this antibody does not detect endogenous Tsl and only recognizes overexpressed Tsl in fixed tissue. Ovaries were then washed five times with PTx and incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa568 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) secondary antibody in PTx. Following washing in PTx, ovarioles were further dissected and mounted on slides in VectaShield (Vector Laboratories). Single confocal sections of stage nine egg chambers were captured on a Nikon C1 confocal microscope at 20× magnification.

Generation of Rab3-GEF5

Transgenic flies expressing two guide RNAs targeting Rab3-GEF (535: 5′-ATC GGT TCG GGA TAG TCT TC-3′; 5244: 5′-AGT CAG GAG CGT GAT ATG AT-3′) were made by cloning annealed guide sequence oligos into the pBFv-U6.2 vector (Kondo and Ueda 2013), followed by genomic integration via ΦC31-mediated transgenesis (attP40 and attP2 landing sites). These flies were crossed to the Cas9 source, and single lines carrying deletions between the two guide RNA target sites were established. The genomic deletion in line five (coordinates: X:15,097,551–15,102,259 inclusive, Drosophila melanogaster release 6.18) removes 4708 bp and is predicted to truncate the Rab3-GEF protein (PC isoform) at residue L546 (of 2084 amino acids) and add a short out-of-frame C-terminal extension of 12 residues. We note that these flies are homozygous viable and fertile.

Data and reagent availability statement

Data and reagents are available upon request. Table S1 contains a list of the BDSC deficiency kit deficiencies that do not suppress the ectopic Tsl phenotype. Table S2 lists the alleles of genes within suppressor regions that were screened.

Results

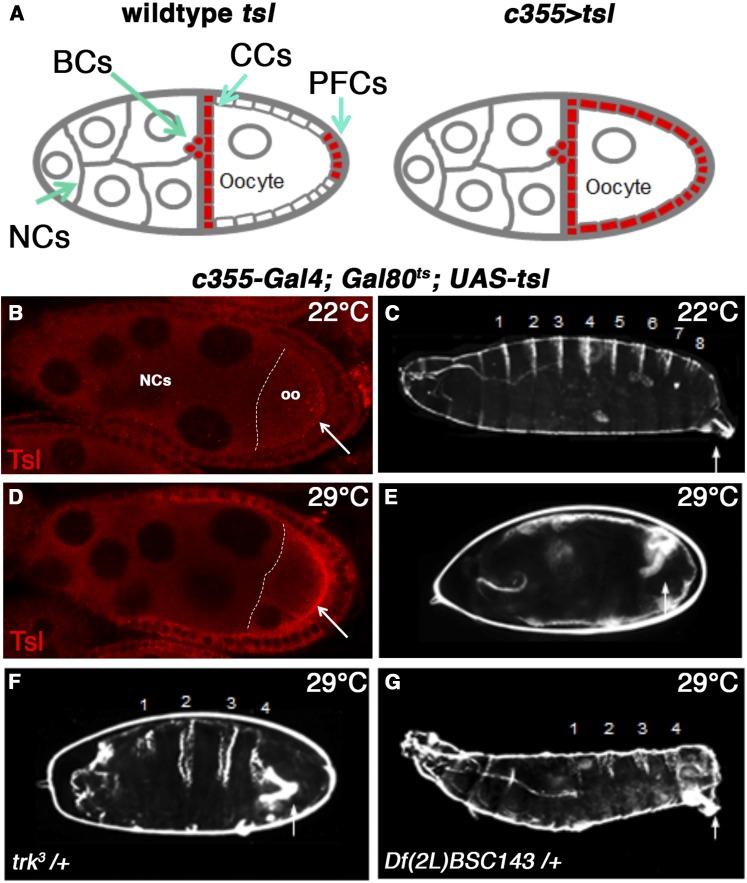

Normally, tsl expression is restricted to subpopulations of follicle cells located at the anterior and posterior ends of the developing oocyte (Savant-Bhonsale and Montell 1993; Martin et al. 1994). Expressing tsl ectopically in all follicle cells (c355-Gal4; UAS-tsl, Figure 1) causes a highly consistent maternal embryonic lethal cuticle phenotype whereby the terminal regions are expanded and all central segments are lost (known as spliced, Savant-Bhonsale and Montell 1993; Martin et al. 1994). Importantly, Tor activation in this scenario is ligand dependent and thus may also be sensitive to loss of genes that function upstream of tor, such as those involved in ligand generation and trafficking, in addition to those that act downstream.

Figure 1.

Validation of the ectopic Tsl suppressor screen. (A) Schematics of stage 10 egg chambers showing the endogenous tsl expression pattern (red, left) and ectopic pattern used for screening (UAS-tsl driven by c355-Gal4, right). (B) A stage-eight egg chamber from a screening line female raised at 22° and immunostained for Tsl. No ectopic Tsl expression is observed in the perivitelline space (open arrow). These flies produce viable offspring with wild-type cuticles containing eight abdominal segments (numbered) and a filzkörper [closed arrow, (C)]. (D) An egg chamber from a screening line female raised at 29° showing strong ectopic expression of Tsl. (E) These flies produce embryos with the lethal spliced phenotype (no abdominal segments and expanded termini). Suppression of ectopic tsl phenotype (gain of multiple abdominal segments) is observed upon introduction of either one copy of the amorphic trk allele, trk3 (F) or Df(2L)BSC143, which deletes one copy of trk (G). Anterior is to the left. BCs, border cells; CCs, centripetal follicle cells; NCs, nurse cells; oo, oocyte; PFCs, posterior follicle cells.

In order to conduct an F1 suppressor screen using this background, we first needed to overcome the maternal sterility associated with ectopic tsl expression. This was necessary to enable the screening line to be crossed directly to chromosomal deficiencies and mutant alleles, and to examine embryos produced by the offspring. We achieved this using the temperature-sensitive (ts) repressor of Gal4, Gal80ts (McGuire et al. 2004). When females (c355-Gal4; Gal80ts; UAS-tsl) were raised at 22°, Gal80ts efficiently prevented ectopic maternal tsl expression (Figure 1B), and females produced embryos with wild-type cuticles (Figure 1C). Raising females at 29°, either from the third instar larval stage or by shifting adults raised at 22° to this temperature, fully restored ectopic tsl expression (Figure 1D) and induced the spliced phenotype (Figure 1E).

To test whether this line was suitable for a suppressor screen, we introduced one copy of a strong hypomorphic allele of trk (trk3), a terminal class gene known to be limiting with respect to Tor signaling (Sprenger and Nusslein-Volhard 1992). This strongly suppressed the ectopic tsl phenotype, as evidenced by restoration of multiple central segments in almost all embryos (Figure 1F). A similar degree of suppression was observed using one copy of a chromosomal deficiency that deletes a genomic region including trk (Df[2L]BSC143; Figure 1G). Taken together, these data suggest that the ectopic tsl phenotype is sensitive to tor pathway gene dosage and may serve as a discovery tool for new pathway components, including genes that act upstream of tor.

To identify regions of the genome that contain novel Tor pathway genes, we performed a screen using the BDSC deficiency kit. This is a collection of 467 lines each containing a genomic deletion with molecularly defined breakpoints, collectively covering ∼98% of euchromatic genes in D. melanogaster (Cook et al. 2012). Of the 467 lines, data were obtained for 429 lines, equating to ∼90% of the genome (Table 1). The remaining lines were mostly deficiencies on the X chromosome that were problematic owing to poor culture health. The screen identified 65 deficiencies that consistently suppressed the ectopic tsl phenotype to varying degrees (Table 2), and 363 deficiencies that showed no suppression (Table S1). Most of the observed suppressor deficiencies were moderate in strength (gain of at least one segment, 44 deficiencies in the primary screen), whereas 17 were scored as strong suppressors (gain of multiple segments), and one was a weak suppressor. Very strong suppression (gain of multiple segments and partially restored viability) was observed for three deficiencies, Df(1)ED7005 and Df(1)ED7289, neither of which span previously known tor pathway genes, and Df(2L)BSC143, which spans trk. We note that seven suppressor deficiencies overlap in the regions they delete, and hence these may represent a single suppressor region. After such cases were accounted for, we estimated there to be at least 59 individual suppressors (hereafter referred to as suppressor regions) across the three major chromosomes (Table 1). To reduce the sizes of the regions and further narrow the list of candidate suppressor genes, mapping was conducted using additional available deficiency lines (Table 2). This markedly reduced the number of candidate genes, leaving 15 genes or fewer in 29 of the regions and five genes or fewer in nine of the regions.

Table 1. Summary of the ectopic tsl suppressor screen.

| Chromosome | BDSC Kit Deficiencies Tested/Total | Suppressor Deficiencies | Minimum Number of Suppressor Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 71/91 | 17 | 13 |

| 2 | 187/190 | 15 | 14 |

| 3 | 165/180 | 33 | 32 |

| 4 | 6/6 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 429/467 | 65 | 59 |

The proportion of the BDSC deficiency kit screened and number of suppressor deficiencies are shown by chromosome. Minimum number of suppressor regions accounts for deficiencies that overlap and may therefore represent a single suppressor deleted by both deficiencies.

We next wanted to identify the genes responsible for the observed suppression in each of these regions. To do this, we used available known loss-of-function and potential loss-of-function mutant alleles, as well as mutant alleles that we generated (Rab3-GEF5, this study; and trkΔ, Henstridge et al. 2014), and tested whether they too could suppress the ectopic tsl phenotype. In total, we tested mutant alleles of 88 genes (Table S2) and successfully identified the causative suppressor gene in 10 of the regions (in addition to trk, Table 3). Four of these genes—Ras oncogene at 85D (Ras85D), Son of sevenless (Sos), tailless (tll), and C-terminal Binding Protein (CtBP)—have known roles in terminal patterning (Pignoni et al. 1990; Simon et al. 1991; Lu et al. 1993; Cinnamon et al. 2004) and thus further validate the screening approach. In each of these cases, the strength of suppression caused by the original deficiency was moderate to strong, and this matched well with the alleles we tested. Notably, many deficiencies that include other previously identified terminal class genes were not identified as suppressors. This suggests that these genes may not be dosage limiting for the ectopic tsl phenotype (Table 4). The remaining six genes that we identified had no previously known involvement in terminal patterning and thus represent potentially novel regulators of the Tor pathway. These genes are: Tetraspanin 3A (Tsp3A), Ribosomal protein S21 (RpS21), RpS26, Protein disulphide isomerase (Pdi), αTub84B, and tws. As suppressors of the ectopic tsl phenotype, our findings suggest that these genes are haploinsufficient with respect to unrestricted Tor signaling.

Table 3. Genes identified as suppressors of the ectopic tsl phenotype.

| Suppressor Region | Suppressor Gene | Allele(s) Tested | Strength of Suppression |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Tetraspanin 3A | Tsp3Ae03287 | ++ |

| 14 | Ribosomal protein S21 | RpS2103575 | ++ |

| RpS21k16804a | ++ | ||

| 17 | Trunk | trk3 | ++++ |

| trkΔ | ++++ | ||

| 18 | Son of Sevenless | Sos34Ea-6 | +++ |

| 20 | Ribosomal protein S26 | RpS26KG00230 | +++ |

| 35 | Protein disulfide isomerase | P{lacW}I(3)j2A2jA2A | +++ |

| 40 | α-Tubulin at 84B | αTub84B5 | ++ |

| 42 | Ras oncogene at 85D | Ras85De1B | ++ |

| 44 | twins | tws02414 | ++ |

| 46 | C-terminal binding protein | CtBP03463 | ++ |

| 58 | tailless | tll49 | +++ |

Mutant alleles used to identify the gene as a suppressor are indicated. The suppression score is listed with the allele identified as a suppressor for this region. Suppression was scored qualitatively based on segment gain and consistency; moderate (++), strong (+++), and very strong (++++). Bolded genes have no previously known involvement in terminal patterning.

Table 4. Terminal class genes not detected as suppressors of the ectopic tsl phenotype.

| Terminal Class Gene(s) | Loss-of-Function Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| closca | Loss of termini | Ventura et al. (2010) |

| fs(1)polehole | Loss of termini | Jimenez et al. (2002) |

| fs(1)Nasrat | Loss of termini | Jimenez et al. (2002) |

| Furin 1 and Furin 2 | Loss of termini | Johnson et al. (2015) |

| torso-like | Loss of termini | Stevens et al. (1990) |

| torso | Loss of termini | Sprenger et al. (1989) |

| corkscrew | Suppressor of tor GOF | Perkins et al. (1992) |

| downstream of receptor kinase | Partial loss of termini | Simon et al. (1991) |

| huckebein | Loss of posterior midgut | Weigel et al. (1990) |

| sprouty | Suppresses torso GOF | Casci et al. (1999) |

| bicoid | Loss of anterior | Driever and Nusslein-Volhard (1988) |

Terminal class gene names and their previously reported loss-of-function phenotypes are given. Note that only genes known to encode positive regulators of tor signaling are shown (i.e., those expected to be suppressors) and the relevant reference is given for each.

Discussion

We were initially surprised by the large number of suppressor regions detected in our screen. A previous screen performed using the torY9 gain-of-function allele found only 26 suppressor regions (Li and Li 2003). Although this study used a different deficiency kit with cytologically defined breakpoints and larger deleted regions, the difference between these figures could also reflect differences in our approaches. Our approach is ligand dependent and also sensitive to dosage-limited genes that act either upstream or downstream of tor. It is therefore possible that the additional suppressor regions we detected contain genes required for generation of the active Tor ligand. In addition, because our screening strategy relied upon Gal4/UAS-driven expression of a tsl transgene, genes required for production of ectopic Tsl (e.g., those involved in protein translation) could act as suppressors. Indeed, the suppressor genes RpS21 and RpS26 that we identified may be haploinsufficient in this regard. Both genes encode crucial structural constituents of the ribosome and are required for protein translation (Marygold et al. 2007). Despite this, five of the 11 genes that we identified in our screen are known terminal patterning genes. Thus, many of the suppressor regions remaining are likely to house genes relevant to Tor signaling rather than suppressors of Gal4-driven tsl expression. A brief discussion of each identified suppressor gene in the context of this screen is given below.

Tetraspanin 3A

Tsp3A is one of 35 known tetraspanin genes in the Drosophila genome (Fradkin et al. 2002). Members of the tetraspanin superfamily are characterized by the presence of four transmembrane segments, and associate with each other and other transmembrane proteins to carry out cellular functions such as migration, fusion, adhesion, immune response, and intracellular vesicle trafficking [for a review, see Zhang and Huang (2012)]. However, the mechanism of tetraspanin function remains poorly understood (Zhang and Huang 2012). The allele of Tsp3A (Tsp3Ae03287) responsible for suppression of the ectopic tsl phenotype is homozygous viable and fertile, and exhibits no terminal patterning defects (data not shown). This could possibly be explained by functional redundancy between Tsp3A and other tetraspanin-encoding genes during normal development, and Tsp3A dosage sensitivity in our screening background. In this regard, Tsp26A and Tsp86D are known to act redundantly with Tsp3A in the promotion of Notch signaling for ovarian border cell migration (Dornier et al. 2012). Whether tetraspanins including Tsp3A have a similar role at the embryo plasma membrane for a Tor signaling factor will be interesting to determine.

Protein disulphide isomerase

Pdi encodes one of the two major protein disulphide isomerases found in Drosophila. The primary function of these enzymes is to form and break disulfide bonds between cysteine residues as proteins fold in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER, Freedman 1989; Noiva and Lennarz 1992). In our screen, Pdi was identified as a strong suppressor and thus may play an important part in terminal patterning. How might it achieve this? The Pdi-like protein Windbeutel (Thioredoxin/ERp29 superfamily; Konsolaki and Schupbach 1998) is required for the trafficking of Pipe through the ovarian follicle cell ER to assist in localizing the signal for dorsoventral patterning (Sen et al. 2000). Thus, Pdi may be essential for the correct folding and/or transport of one or more key Tor signaling components. This could include genes that function at the level of the ligand, receptor, or downstream pathway components.

α-Tubulin at 84B

α- and β-Tubulin proteins are the major structural constituents of the eukaryotic microtubule (MT, Nogales 2001). D. melanogaster has three α- and four β-Tubulin-encoding genes; however, no other tubulin genes were found to be suppressors of the ectopic tsl phenotype (βTub85D and βTub97EF were not tested). MTs are cylindrical organelles essential for many cellular processes, including intracellular transport, signal transduction, mitosis, and maintenance of cell shape (Ludueñna 1998; Gundersen and Cook 1999; Nogales 2001). Interestingly, members of the MAPK signaling cascade, including the extracellular signal regulated kinases, were first identified as MT-associated protein kinases (Reszka et al. 1995; Morishima-Kawashima and Kosik 1996). These interactions are thought to regulate kinase activity and permit intracellular protein transport for efficient signal transduction (Parker et al. 2014). One possibility, therefore, is that αTub84B is important for promoting MAPK signaling downstream of Tor.

twins

tws encodes one of three different B subunit classes of the heterotrimeric serine/threonine phosphatase complex known as protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A, Mumby and Walter 1993; Walter and Mumby 1993). PP2A is composed of a scaffold A subunit, a regulatory B subunit, and a catalytic C subunit that together form the active holoenzyme (Janssens and Goris 2001). The B subunits provide temporal and spatial specificity for PP2A activity (Zolnierowicz et al. 1994; Janssens and Goris 2001; Seshacharyulu et al. 2013).

tws has been shown to have roles in a wide variety of cellular processes in Drosophila, including cell fate determination (Mumby and Walter 1993), cell cycle regulation (Walter and Mumby 1993), centriole amplification (Brownlee et al. 2011), and neuroblast proliferation and self-renewal (Chabu and Doe 2009). Most notably, tws has been identified as a suppressor of a constitutively active form of Sevenless, an RTK with strong homology to Tor (Maixner et al. 1998). It is possible that Tws acts similarly downstream of Tor in terminal patterning. The maternal role of tws has previously been investigated in three different studies; however, the results of these are conflicting. Germline clone analyses using the twsj11C8 allele by Bajpai et al. (2004) showed that embryos arrested prior to segmentation, whereas Perrimon et al. (1996) observed patterning defects resulting in the variable deletion of segments using the tws02414 allele that we used here. Finally, Bellotto et al. (2002) reported terminal defects associated with l(3)S027313, a lethal but unmapped P-element insertion. This insertion was later mapped to the tws locus (Deak et al. 1997), thus further supporting the idea that tws is essential for terminal patterning.

Conclusion

We have performed a genome-wide suppressor screen for genes that act downstream of tsl in embryonic terminal patterning, and identified several new Tor pathway regulators. Many of the suppressor regions where the causative gene(s) are yet to be identified have been mapped to a tractable number of candidate genes. Thus, the generation of new loss-of-function alleles for candidate genes in these suppressor regions will permit the rapid discovery of new genes involved in Tor signaling. This will be particularly informative with respect to unanswered questions, including how the Tor ligand is generated and, more broadly, how RTK signaling is spatially controlled and transduced.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.g3journal.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/g3.117.300491/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Heaney, the Australian Drosophila Biomedical Research Facility (OzDros), and Monash Micro Imaging for technical support. We thank the Bloomington and Kyoto Drosophila Stock Centers and David Hipfner for providing fly stocks. M.A.H. is a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Early Career Fellow. T.K.J. is an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Researcher Award Fellow. J.C.W. is a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellow, and he further acknowledges the support of an ARC Federation Fellowship. This project was supported by an ARC grant to J.C.W. and C.G.W., and used resources developed under a Monash University Interdisciplinary Research Grant award.

Author contributions: T.K.J., C.G.W., and J.C.W. conceived the experiments, interpreted the data, and led the work. A.R.J., M.A.H., M.J.S., K.A.M., and T.K.J. performed the experiments. A.R.J., M.A.H., J.C.W., C.G.W., and T.K.J. wrote the article.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: A. Bashirullah

Literature Cited

- Amarnath S., Stevens L. M., Stein D. S., 2017. Reconstitution of Torso signaling in cultured cells suggests a role for both Trunk and Torso-like in receptor activation. Development 144: 677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai R., Makhijani K., Rao P. R., Shashidhara L. S., 2004. Drosophila twins regulates Armadillo levels in response to Wg/Wnt signal. Development 131: 1007–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellotto M., Bopp D., Senti K. A., Burke R., Deak P., et al. , 2002. Maternal-effect loci involved in Drosophila oogenesis and embryogenesis: p element-induced mutations on the third chromosome. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 46: 149–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brönner G., Jäckle H., 1991. Control and function of terminal gap gene activity in the posterior pole region of the Drosophila embryo. Mech. Dev. 35: 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee C. W., Klebba J. E., Buster D. W., Rogers G. C., 2011. The protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit twins stabilizes Plk4 to induce centriole amplification. J. Cell Biol. 195: 231–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali A., Casanova J., 2001. The spatial control of Torso RTK activation: a C-terminal fragment of the trunk protein acts as a signal for Torso receptor in the Drosophila embryo. Development 128: 1709–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J., Furriols M., McCormick C. A., Struhl G., 1995. Similarities between trunk and spatzle, putative extracellular ligands specifying body pattern in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 9: 2539–2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casci T., Vinos J., Freeman M., 1999. Sprouty, an intracellular inhibitor of Ras signaling. Cell 96: 655–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabu C., Doe C. Q., 2009. Twins/PP2A regulates aPKC to control neuroblast cell polarity and self-renewal. Dev. Biol. 330: 399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinnamon E., Gur-Wahnon D., Helman A., St Johnston D., Jimenez G., et al. , 2004. Capicua integrates input from two maternal systems in Drosophila terminal patterning. EMBO J. 23: 4571–4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook R. K., Christensen S. J., Deal J. A., Coburn R. A., Deal M. E., et al. , 2012. The generation of chromosomal deletions to provide extensive coverage and subdivision of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Biol. 13: R21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak P., Omar M. M., Saunders R. D. C., Pal M., Komonyi O., et al. , 1997. P-element insertion alleles of essential genes on the third chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster: correlation of physical and cytogenetic maps in chromosomal region 86E–87F. Genetics 147: 1697–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornier E., Coumailleau F., Ottavi J. F., Moretti J., Boucheix C., et al. , 2012. TspanC8 tetraspanins regulate ADAM10/Kuzbanian trafficking and promote Notch activation in flies and mammals. J. Cell Biol. 199: 481–496 (erratum: J. Cell. Biol. 213: 495–496). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever W., Nusslein-Volhard C., 1988. The bicoid protein determines position in the Drosophila embryo in a concentration-dependent manner. Cell 54: 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudkina N. V., Spicer B. A., Reboul C. F., Conroy P. J., Lukoyanova N., et al. , 2016. Structure of the poly-C9 component of the complement membrane attack complex. Nat. Commun. 7: 10588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fradkin L. G., Kamphorst J. T., DiAntonio A., Goodman C. S., Noordermeer J. N., 2002. Genomewide analysis of the Drosophila tetraspanins reveals a subset with similar function in the formation of the embryonic synapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 13663–13668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R. B., 1989. Protein disulfide isomerase: multiple roles in the modification of nascent secretory proteins. Cell 57: 1069–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen G. G., Cook T. A., 1999. Microtubules and signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11: 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henstridge M. A., Johnson T. K., Warr C. G., Whisstock J. C., 2014. Trunk cleavage is essential for Drosophila terminal patterning and can occur independently of Torso-like. Nat. Commun. 5: 3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens V., Goris J., 2001. Protein phosphatase 2A: a highly regulated family of serine/threonine phosphatases implicated in cell growth and signalling. Biochem. J. 353: 417–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez G., Gonzalez-Reyes A., Casanova J., 2002. Cell surface proteins nasrat and polehole stabilize the Torso-like extracellular determinant in Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 16: 913–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. K., Crossman T., Foote K. A., Henstridge M. A., Saligari M. J., et al. , 2013. Torso-like functions independently of Torso to regulate Drosophila growth and developmental timing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 14688–14692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. K., Henstridge M. A., Herr A., Moore K. A., Whisstock J. C., et al. , 2015. Torso-like mediates extracellular accumulation of Furin-cleaved Trunk to pattern the Drosophila embryo termini. Nat. Commun. 6: 8759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S., Ueda R., 2013. Highly improved gene targeting by germline-specific Cas9 expression in Drosophila. Genetics 195: 715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konsolaki M., Schupbach T., 1998. Windbeutel, a gene required for dorsoventral patterning in Drosophila, encodes a protein that has homologies to vertebrate proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 12: 120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law R. H. P., Lukoyanova N., Voskoboinik I., Caradoc-Davies T. T., Baran K., et al. , 2010. The structural basis for membrane binding and pore formation by lymphocyte perforin. Nature 468: 447–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Li W. X., 2003. Drosophila gain-of-function mutant RTK torso triggers ectopic Dpp and STAT signaling. Genetics 164: 247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. X., 2005. Functions and mechanisms of receptor tyrosine kinase Torso signaling: lessons from Drosophila embryonic terminal development. Dev. Dyn. 232: 656–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Chou T. B., Williams N. G., Roberts T., Perrimon N., 1993. Control of cell fate determination by p21ras/Ras1, an essential component of torso signaling in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 7: 621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludueña R. F., 1998. Multiple forms of tubulin: different gene products and covalent modifications. Int. Rev. Cytol. 178: 207–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luschnig S., Moussian B., Krauss J., Desjeux I., Perkovic J., et al. , 2004. An F1 genetic screen for maternal-effect mutations affecting embryonic pattern formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 167: 325–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maixner A., Hecker T. P., Phan Q. N., Wassarman D. A., 1998. A screen for mutations that prevent lethality caused by expression of activated sevenless and Ras1 in the Drosophila embryo. Dev. Genet. 23: 347–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. R., Raibaud A., Ollo R., 1994. Terminal pattern elements in Drosophila embryo induced by the torso-like protein. Nature 367: 741–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marygold S. J., Roote J., Reuter G., Lambertsson A., Ashburner M., et al. , 2007. The ribosomal protein genes and minute loci of Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Biol. 8: R216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire S. E., Mao Z., Davis R. L., 2004. Spatiotemporal gene expression targeting with the TARGET and gene-switch systems in Drosophila. Sci. STKE 2004: pl6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima-Kawashima M., Kosik K. S., 1996. The pool of map kinase associated with microtubules is small but constitutively active. Mol. Biol. Cell 7: 893–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby M. C., Walter G., 1993. Protein serine/threonine phosphatases: structure, regulation, and functions in cell growth. Physiol. Rev. 73: 673–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales E., 2001. Structural insight into microtubule function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 30: 397–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noiva R., Lennarz W. J., 1992. Protein disulfide isomerase. A multifunctional protein resident in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 3553–3556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslein-Volhard C., Frohnhofer H. G., Lehmann R., 1987. Determination of anteroposterior polarity in Drosophila. Science 238: 1675–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker A. L., Kavallaris M., McCarroll J. A., 2014. Microtubules and their role in cellular stress in cancer. Front. Oncol. 4: 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins L. A., Larsen I., Perrimon N., 1992. Corkscrew encodes a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase that functions to transduce the terminal signal from the receptor tyrosine kinase torso. Cell 70: 225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrimon N., Lanjuin A., Arnold C., Noll E., 1996. Zygotic lethal mutations with maternal effect phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster. II. Loci on the second and third chromosomes identified by P-element-induced mutations. Genetics 144: 1681–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignoni F., Baldarelli R. M., Steingrimsson E., Diaz R. J., Patapoutian A., et al. , 1990. The Drosophila gene tailless is expressed at the embryonic termini and is a member of the steroid receptor superfamily. Cell 62: 151–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reszka A. A., Seger R., Diltz C. D., Krebs E. G., Fischer E. H., 1995. Association of mitogen-activated protein kinase with the microtubule cytoskeleton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 8881–8885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado C. J., Kondos S., Bull T. E., Kuiper M. J., Law R. H., et al. , 2008. The MACPF/CDC family of pore-forming toxins. Cell. Microbiol. 10: 1765–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savant-Bhonsale S., Montell D. J., 1993. Torso-like encodes the localized determinant of Drosophila terminal pattern formation. Genes Dev. 7: 2548–2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupbach T., Wieschaus E., 1986. Germline autonomy of maternal-effect mutations altering the embryonic body pattern of Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 113: 443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupbach T., Wieschaus E., 1989. Female sterile mutations on the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. I. Maternal effect mutations. Genetics 121: 101–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen J., Goltz J. S., Konsolaki M., Schupbach T., Stein D., 2000. Windbeutel is required for function and correct subcellular localization of the Drosophila patterning protein Pipe. Development 127: 5541–5550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshacharyulu P., Pandey P., Datta K., Batra S. K., 2013. Phosphatase: PP2A structural importance, regulation and its aberrant expression in cancer. Cancer Lett. 335: 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M. A., Bowtell D. D., Dodson G. S., Laverty T. R., Rubin G. M., 1991. Ras1 and a putative guanine nucleotide exchange factor perform crucial steps in signaling by the sevenless protein tyrosine kinase. Cell 67: 701–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger F., Nusslein-Volhard C., 1992. Torso receptor activity is regulated by a diffusible ligand produced at the extracellular terminal regions of the Drosophila egg. Cell 71: 987–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger F., Stevens L. M., Nusslein-Volhard C., 1989. The Drosophila gene torso encodes a putative receptor tyrosine kinase. Nature 338: 478–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger F., Trosclair M. M., Morrison D. K., 1993. Biochemical analysis of torso and D-raf during Drosophila embryogenesis: implications for terminal signal transduction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 1163–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens L. M., Frohnhofer H. G., Klingler M., Nusslein-Volhard C., 1990. Localized requirement for torso-like expression in follicle cells for development of terminal anlagen of the Drosophila embryo. Nature 346: 660–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D., Nüsslein-Volhard C., 1992. The origin of pattern and polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Cell 68: 201–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecker T. R., Yip M. L., Lipshitz H. D., 1991. Zygotic genes that mediate torso receptor tyrosine kinase functions in the Drosophila melanogaster embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 5824–5828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura G., Furriols M., Martin N., Barbosa V., Casanova J., 2010. closca, a new gene required for both Torso RTK activation and vitelline membrane integrity. Germline proteins contribute to Drosophila eggshell composition. Dev. Biol. 344: 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter G., Mumby M., 1993. Protein serine/threonine phosphatases and cell transformation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1155: 207–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D., Jurgens G., Klingler M., Jackle H., 1990. Two gap genes mediate maternal terminal pattern information in Drosophila. Science 248: 495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. A., Huang C., 2012. Tetraspanins and cell membrane tubular structures. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69: 2843–2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnierowicz S., Csortos C., Bondor J., Verin A., Mumby M. C., et al. , 1994. Diversity in the regulatory B-subunits of protein phosphatase 2A: identification of a novel isoform highly expressed in brain. Biochemistry 33: 11858–11867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.