Abstract

Background. Deficiencies in older people’s social relationships (including loneliness, social isolation, and low social support) have been implicated as a cause of premature mortality and increased morbidity. Whether they affect service use is unclear.

Objectives. To determine whether social relationships are associated with older adults’ use of health services, independently of health-related needs.

Search Methods. We searched 8 electronic databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination) for data published between 1983 and 2016. We also identified relevant sources from scanning the reference lists of included studies and review articles, contacting authors to identify additional studies, and searching the tables of contents of key journals.

Selection Criteria. Studies met inclusion criteria if more than 50% of participants were older than 60 years or mean age was older than 60 years; they included a measure of social networks, received social support, or perceived support; and they reported quantitative data on the association between social relationships and older adults’ health service utilization.

Data Collection and Analysis. Two researchers independently screened studies for inclusion. They extracted data and appraised study quality by using standardized forms. In a narrative synthesis, we grouped the studies according to the outcome of interest (physician visits, hospital admissions, hospital readmissions, emergency department use, hospital length of stay, utilization of home- and community-based services, contact with general health services, and mental health service use) and the domain of social relationships covered (social networks, received social support, or perceived support). For each service type and social relationship domain, we assessed the strength of the evidence across studies according to the quantity and quality of studies and consistency of findings.

Main Results. The literature search retrieved 26 077 citations, 126 of which met inclusion criteria. Data were reported across 226 678 participants from 19 countries. We identified strong evidence of an association between weaker social relationships and increased rates of readmission to hospital (75% of high-quality studies reported evidence of an association in the same direction). In evidence of moderate strength, according to 2 high-quality and 3 medium-quality studies, smaller social networks were associated with longer hospital stays. When we considered received and perceived social support separately, they were not linked to health care use. Overall, the evidence did not indicate that older patients with weaker social relationships place greater demands on ambulatory care (including physician visits and community- or home-based services) than warranted by their needs.

Authors’ Conclusions. Current evidence does not support the view that, independently of health status, older patients with lower levels of social support place greater demands on ambulatory care. Future research on social relationships would benefit from a consensus on clinically relevant concepts to measure.

Public Health Implications. Our findings are important for public health because they challenge the notion that lonely older adults are a burden on all health and social care services. In high-income countries, interventions aimed at reducing social isolation and loneliness are promoted as a means of preventing inappropriate service use. Our review cautions against assuming that reductions in care utilization can be achieved by intervening to strengthen social relationships.

PLAIN-LANGUAGE SUMMARY

We looked at published research on the link between older adults’ use of health services and their social relationships (including loneliness, isolation, and social support). We searched 8 electronic databases for studies published between 1983 and 2016. We identified more than 26 000 articles. We included 126 studies in our review, providing information on 226 678 people from 19 countries. We found strong evidence of a link between weaker social relationships and readmissions to hospital but no evidence on the use of community services or emergency departments. Evidence of moderate strength linked larger social networks to shorter hospital stays. We conclude that current evidence does not support the idea that older patients with low levels of social support use more ambulatory care than they need. Our study suggests that campaigns to reduce isolation or loneliness may not reduce utilization of ambulatory care services, though strengthening social support could shorten hospital stays and prevent some readmissions.

Over the past decade, the quantity and quality of social relationships in later life have become a major societal concern. Across Europe and North America, national campaigns have been set up to “end loneliness in older age” (Coalitie Erbij, Netherlands; Campaign to End Loneliness, United Kingdom), “mobilize society against isolation in the elderly” (MONALISA, France), strengthen older adults’ social connections (“Connect2affect,” United States), and “Reach Isolated Seniors Everywhere” (RISE, Canada). One of the drivers of these campaigns is the growing body of research associating social relationships with mortality and morbidity: recent meta-analyses have shown that individuals with weaker social ties are on average 30% more likely to die early or to develop cardiovascular disease.1,2

The implications of older adults’ relationships for health care utilization are unclear. It is often claimed that dissatisfaction with the quality and quantity of one’s relationships leads to inappropriate consultations with health professionals, and that interventions aimed at strengthening social relationships could help to prevent avoidable health care utilization (e.g., The Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015).3 Older adults who lack social relationships and feel isolated report lower levels of self-rated physical health,4 which can prompt them to consult a physician more frequently than socially connected individuals.5 Seeking medical assistance might also be a way for them to satisfy an unmet need for interpersonal interaction and stimulation.6 Conversely, it may be that older adults who have limited access to social relationships and the support they provide (e.g., transportation, financial aid, health-related advice)7 place fewer demands on health services; if so, their infrequent contacts would be a precious opportunity for health monitoring or preventive care.8

To date, individual studies have reported conflicting findings on the association between social relationships and family doctor visits, hospital admissions, or emergency department attendances.9–13 Some of this variation may reflect the range of ways in which social relationships have been operationalized in the literature, from subjective appraisals of relationship quality to more objective measures of social contact.14 In their behavioral model of health care utilization, Andersen et al. suggest that both subjective aspects, such as the perceived availability of support, and objective characteristics such as social network composition and size, are important for accessing services.15 This model does not, however, indicate which of these aspects of relationships might be more influential; nor does it specify whether they are barriers to, or facilitators of, care utilization. To determine the nature and direction of effect between different dimensions of social relationships and older adults’ use of health services, we set out to systematically review the empirical evidence.

METHODS

Our study followed the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s Guidance for undertaking reviews in health care.16 We registered a protocol with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number: CRD42016045682).

Search Strategy

Using a combination of index and free-text terms, we searched 8 databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination) for literature published up until July 2016 (see Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for an example of the search strategy used in MEDLINE). We also searched the reference lists of all included studies and review articles, contacted authors to identify additional studies, and scanned tables of contents of key journals for additional reports of relevance.

Selection Criteria

Researchers commonly distinguish between 3 major dimensions of social relationships: (1) the structure of a person’s social network (e.g., frequency of contact with family and friends), (2) the objective availability of social support (e.g., whether someone receives emotional, informational, tangible, or belonging support), and (3) subjective perceptions of social support (e.g., the perceived adequacy of the quantity or quality of one’s relationships, or feelings of loneliness).17 The evidence to date does not suggest that one dimension may be more problematic for service use than the others; we therefore included studies if they investigated any one of these dimensions and reported quantitative data on health service utilization. Our aim was to study the implications of both the quantity and the quality of social relationships; because marital status, living arrangement, or number of relatives provide limited information on relationship quality or quantity (e.g., people may be married or parents but not see their spouse or child), these measures qualified for inclusion only when combined with an assessment of contact frequency or appraisal of relationship quality.

Because the focus for this review was on older people, we excluded studies in which less than 50% of the sample was older than 60 years or in which mean age was younger than 60 years. To ensure that our findings were relevant to the current context of service delivery and disease burden in high-income settings, we excluded work conducted in low- and middle-income countries as defined by the World Bank and we restricted our search to studies published in the past 25 years. We excluded reports written in languages other than those read by the research team (English, French, Spanish, or Italian) because of resource constraints.

Title and Abstract Review, Data Extraction

Two researchers independently checked the titles and abstracts of the articles identified through our search. They then extracted data from the studies that met inclusion criteria into a standardized form that captured study design, data collection methods, participant characteristics, predictor and outcome variables, methods of statistical analysis, and findings relevant to the review. We extracted results of statistical tests (95% confidence intervals for relative risk, odds or hazard ratios, and P values) where reported; when data were missing or unclear, we contacted authors.

Quality Assessment

We appraised the quality of individual studies by using the standardized scale developed by Gomes and Higginson.18 We graded studies as high quality if they had used multivariate analysis and scored 70% or higher; medium quality if they included multivariate analysis but scored less than 70%, or did not include multivariate analysis but scored at least 60%; and poor quality if no multivariate analysis was presented and it scored less than 60%. Three reviewers assessed the studies and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data Synthesis

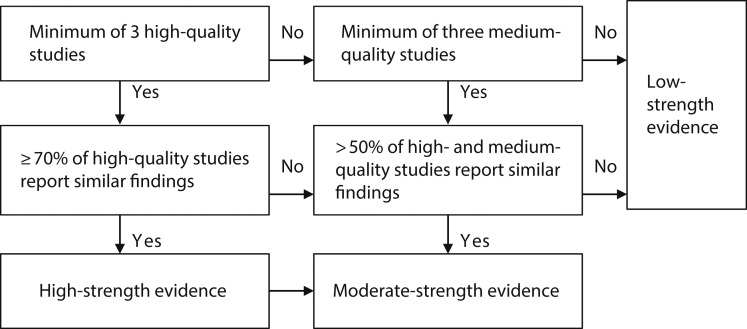

We did not attempt meta-analysis because of heterogeneity in study design, population, social relationship measure, and outcome assessment (see Appendix B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for details of each study). Instead, we conducted a narrative synthesis according to the stages outlined in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance: preliminary synthesis, exploration of relationships within and between studies, and robustness assessment.16 After grouping studies according to the outcomes and dimensions of social relationships on which they reported, we systematically assessed the strength of the evidence for each type of service and social relationship domain by using the algorithm presented in Figure 1. We then compared the strength of the evidence across different measures of relationships for each service type and across service types. When writing up our findings, we gave more weight and space to studies with a lower risk of bias; results from medium- and low-quality studies are discussed only when they provided additional insights into the literature.

FIGURE 1—

Algorithm Used to Grade Strength of Evidence

Note. Example of how we applied this to the evidence on perceived social support and family physician visits: we identified 4 studies, 3 of high quality and 1 of medium quality. Less than 70% of high-quality studies (2 out of 3) but more than 50% of high- and medium-quality studies (3 out of 4) reported no evidence of effect; we therefore rated the evidence as being of moderate strength.

Source. Adapted from Gomes and Higginson.18

RESULTS

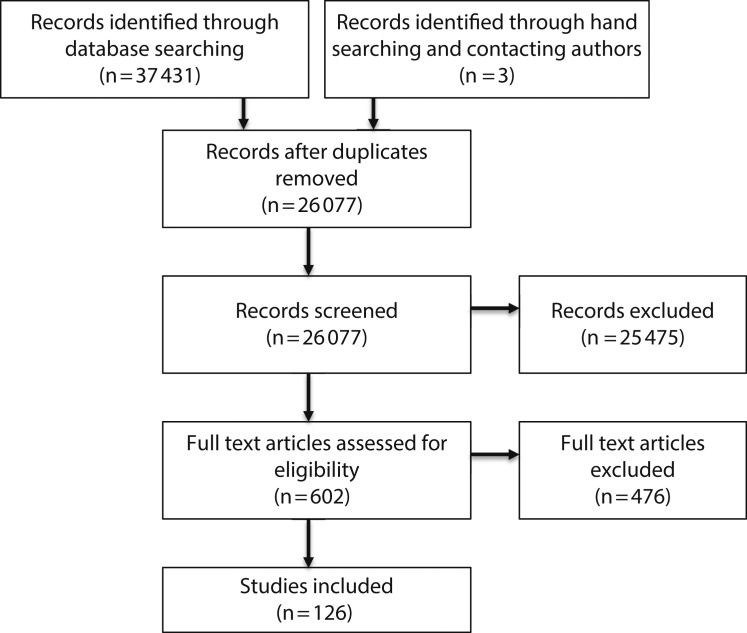

Of the 26 074 citations identified via our electronic search, 123 references met our inclusion criteria; we found an additional 3 articles through hand searching and contacting authors (see Figure 2 for a flow diagram of the study selection process). These 126 articles were based on 104 data sources and reported information from 226 678 participants across 19 different high-income countries, primarily from the United States (59 studies) and Canada (18 studies). Sample sizes ranged from 38 to 100 894 and more than a third of articles (39.6%) contained secondary analyses of previously collected data. Study designs included 1 randomized controlled trial,19 38 (30.2%) longitudinal cohort studies with follow-up times ranging from 14 days to 6 years,10–12,20–54 76 (60.3%) cross-sectional studies,9,13,55–128 and 11 (8.7%) case–control studies.129–139

FIGURE 2—

PRISMA Flowchart of Study Selection for Systematic Review of Social Relationships and Health Care Service Use by Older Adults

The main outcomes investigated were physician visits (26 studies), hospital admissions (26 studies), hospital readmissions (15 studies), emergency department visits (10 studies), hospital length of stay (15 studies), and use of home- and community-based services such as home health aides, visiting nurses, congregate meals, Meals on Wheels, or transportation (53 studies). Social network was the most commonly measured aspect of social relationships (59 studies); 27 studies assessed the objective availability of supportive relationships, 47 studies included a measure of perceptions of relationships, and 29 studies used a multidimensional measure (i.e., a measure that combined 2 or more of these 3 dimensions). Quality scores varied widely, ranging from 31% to 90%; we classed 61 studies as high quality, 53 as medium, and 12 as low. The strength of the evidence for each outcome and measure of social relationships is summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1—

Social Relationships and Health Care Service Use by Older Adults: Strength of, and Message From, the Evidence From a Systematic Review of the Literature: 1983 to 2016

| High-Strength Evidence |

|||||

| Dependent Variable | Measure of Social Relationships | Relationship With Service Use | Consistencya | No. of Participants | Moderate-Strength Evidenceb: Relationship With Service Use |

| Family physician visits | Social network | No evidence of association9,12,78 | |||

| Perceived support | No evidence of association12,32,78 | ||||

| Physician visits (across specialties) | Combined measure | No evidence of association66–68, 81,113 | |||

| Hospital admission | Social network | No evidence of association10,20,25,27,29,103,105,106,108,125,127 | |||

| Received support | No evidence of association29,56 | ||||

| Perceived support | No evidence of association13,25,105,108,110 | ||||

| Combined | No evidence of association42,45,67,68,81 | ||||

| Readmission to hospital | Perceived support | No evidence of association26,31,33 | |||

| Combined | Weaker social relationships were associated with greater likelihood of readmission34,46,48 | 75 (3/4) | 1 176 | ||

| Length of hospital stay | Social network | Smaller social networks were associated with spending more days in hospital19,98,106,108,127 | |||

| Perceived support | No evidence of association33,108,110 | ||||

| Combined | No effect23,69,97 | ||||

| Emergency department visit | Social network | No evidence of association11,77,125 | 75 (3/4) | 3754 | |

| Perceived support | No evidence of association11,77,104 | ||||

| General home- and community-based services | Social network | No evidence of association37,52,54,82,83,92,124,127 | 89 (8/9) | 10 029c | |

| Received support | No evidence of association50,51,72,82,83,92,94,107,121,129 | ||||

| Perceived support | No evidence of association21,37,82,110,120 | 83 (5/6) | 4 049 | ||

| Senior and day center use | Perceived support | No evidence of association59,62 | |||

| General health service use | Social network | No evidence of association52,112 | |||

Percentage of high-quality studies reporting an effect in the same direction (number of high-quality studies reporting the same effect or number of high-quality studies included).

Domains for which the evidence was of low strength (e.g., received support and family physician visits), either because there were fewer than 3 medium-quality studies on the topic or because fewer than 50% of medium- or high-quality studies agreed, are not included in this table.

Two studies used data from the 1988 National Survey of Hispanic Elderly People; when totaling number of participants, we only entered the biggest sample number (Tran124) to avoid counting individuals multiple times.

Physician Contact

Contacts with family physicians were the subject of 5 studies, and visits to physicians in general (i.e., where specialty was not specified) were analyzed in 21 studies.

Contacts with family physicians.

Of the 5 studies that examined the association between social relationships and visits to family physicians, 3 were of high and 2 of medium quality. The evidence on social networks and perceived support was mixed, though in both cases more than 50% of medium- and high-quality studies reported no evidence of association. In 1 high-quality study, loneliness (i.e., the negative feeling associated with people judging that the quantity or quality of relationships is inadequate) was weakly but significantly associated with general practitioner contact in Denmark, whereas having access to a social network was not.9 Conversely, another high-quality study found no association between the perceived availability of help or close relationships and number of visits to a general practitioner in Australia, but reported that men with larger social networks were more likely to have at least some contact with their general practitioner.12 In the third high-quality study, perceived availability of support was unrelated to service use among Dutch patients with Parkinson’s disease.32 Social network, meanwhile, did not explain variation among frequent users of family physician services in Canada.78 We identified no study on received support and only 1 medium-quality study with a multidimensional measure of relationships.

Contact with all physicians.

Nine high-quality, 10 medium-quality, and 3 low-quality studies reported data on visits to physicians in general. Overall, they did not clearly identify social relationships as either enabling or preventing service use. Two high-quality studies on perceived support produced mixed results.35,38 A medium-quality study found no evidence of association once potential confounders had been adjusted for, and another suggested that loneliness may be associated with greater physician utilization among older US women.63,108 Evidence for the effect of received support and access to social networks was similarly mixed.27,29,53,56,61,101,106,108,125,127 When assessed with a multidimensional measure, social relationships did not tend to predict physician use.66,68,81,113

Hospital Use

Hospital admission.

Twenty-six studies considered the influence of social relationships on hospital admissions. Fifteen of these were of high quality, 9 were scored as medium, and 1 as low quality. A majority found no evidence for an association between social relationships and admission to hospital. Eleven out of 16 studies with a measure of social network—5 of which used data from the American Longitudinal Study of Aging—reported that contact with friends or relatives was not significantly associated with hospitalization.10,20,25,27,29,103,105,106,108,125,127 The remaining studies identified limited social contact as a predictor of hospital admission,13,96,134,136 with a further study suggesting that this was only the case among recently widowed women.39 Although Canadians who received more assistance with activities of daily living were more likely to be hospitalized,110 there was no evidence of association between received support and hospitalization among US community dwellers.29,56 Evidence on perceived support was mixed, with 5 studies reporting no association,13,25,105,108,110 2 suggesting that feeling more supported was associated with lesser likelihood of admission,35,103 and 2 reporting mixed results.10,30 When relationships were assessed with a multidimensional measure, they did not predict hospital admission.42,45,66,81

Hospital readmission.

Readmission to hospital was assessed in 11 high- and 4 medium-quality studies. Having a smaller social network was associated with increased risk of readmission in 2 high-quality studies,49,96 though secondary analysis of data from American Longitudinal Study of Aging found no association.127 Having an informal carer predicted greater likelihood of rehospitalization in 1 high-quality study,24 but a second found no evidence of association.28 Although perceived support was identified as a risk factor for readmission in 2 medium-quality studies,43,108 evidence from high-quality studies did not support this.31,33 Three out of the 4 high-quality studies that used a multidimensional measure found that weaker social relationships were associated with greater likelihood of readmission.34,46,48

Length of time spent in hospital.

Our search retrieved 15 studies with data on social relationships and hospital length of stay. Six were of high quality, 8 were of medium quality, and 1 scored as low quality. The 5 studies with a measure of social network all reported findings that showed an inverse relationship between social network size and length of time spent in hospital, though in the case of the 2 studies that used American Longitudinal Study of Aging data, it was contact with nonkin, rather than family members, that made a difference.19,98,106,108,127 Whereas findings from 1 high- and 1 medium-quality study suggested that lower perceived support was associated with more days spent in hospital for cardiac patients in North America70 and chronic heart failure patients in Sweden,43 3 other studies found no relationship with length of hospital stay.33,108,110 We identified moderate-strength evidence suggesting that social relationships measured with a multidimensional tool were not significantly associated with time spent in hospital, on the basis of null findings from 3 medium-quality studies set in Australia, Spain, and Denmark.23,69,97

Emergency department use.

Of the 10 studies that considered emergency department attendance in their analyses, 5 were of high quality, 4 were of medium quality, and 1 was of low quality. In 2 high-quality cross-sectional studies from Israel and 1 prospective cohort from the United States, amount of social interaction did not affect emergency department usage.11,77,125 In a fourth study from Ireland, having a smaller social network was associated with greater emergency department utilization, as was loneliness—but not the perceived availability of support.13 The other studies on perceived support did not report evidence of an association.11,77,104 High-quality studies found no association between emergency department visits and receipt of support or social relationships as measured with a multidimensional tool.11,75

Other Services

Home- and community-based service use.

Forty-four studies examined the association between social relationships and services provided in the home or community (as opposed to within an institution or other isolated setting). There were 19 high-quality studies, 21 medium-quality studies, and 4 low-quality studies. When social network and received or perceived support were measured separately, most studies reported no evidence of association: of the 9 high-quality studies on social network, 8 found no association with service utilization,37,52,54,82,83,92,124,127 and perceived support did not predict service use in 5 out of 6 high-quality studies.21,37,82,110,120 Seven high- and medium-quality studies found no association between received support and service use,21,76,82,120,129,131,137 with a further 3 reporting null results for specific services (rehabilitative care), populations (people living alone), or type of support (help with activities of daily living).50,83,92 In 3 of the 8 studies that used a multidimensional measure of relationships, stronger social ties were associated with greater service use,75,88,126 but the remainder of the evidence was mixed.32,65,86,99,120

Senior center and day center use.

Ten studies—5 of high, 3 of medium, and 2 of low quality—presented evidence on the association between social relationships and senior or day center use. Two of the 4 high- and medium-quality studies with a measure of social networks found that older adults who frequently interacted with family and friends were more likely to attend senior centers,62,87 whereas 1 reported mixed findings83 and 1 no effect.80 High-quality studies identified no relationship between lower received83 or perceived59,62 social support and center use. Only 1 study, of high quality, found evidence of a positive association between a multidimensional measure of social relationships and center use.90

General health service use.

Eight high-quality and 2 medium-quality studies reported data on multiple health service use. Social network size was unrelated to service utilization in 2 high-quality studies,52,112 with a further 2 reports suggesting variation according to whether networks involved kin or nonkin members.114,139 The 1 study on received support found no evidence of association with health care utilization.110 Although 1 high-quality study from the United States found that the perceived availability of support was associated with lesser likelihood of medical service use,21 another reported no evidence of association.110 A third study from Canada found that among people seeking help for psychological distress, community dwellers who reported minimal social support used health services less.111 The evidence from studies with a multidimensional measure of relationships was also mixed, with 1 high-quality study reporting an inverse association with health service utilization in Canada75 and another from Israel identifying participants with a diversified network as making greatest and most recent use of services.95

Mental health service use.

All 5 studies on social relationships and mental health service use were of medium quality. Two studies reported that having access to social relationships (received support or relationships as measured by a multidimensional tool) was associated with lesser use of services,32,132 and 3 studies reported no association with service utilization.57,115,133

Medication, preventive services, cancer support, ambulance, and hospital social work services.

Small numbers of studies with different measures of relationships on medication use (2 studies58,81), preventive services (1 study84), cancer support services (2 studies71,74), ambulance use (1 study41), and hospital social work services (1 study55) did not allow us to gauge the effect of social relationships on these outcomes in this review.

DISCUSSION

We found strong evidence of an association between social relationships measured by using a multidimensional measure and the likelihood of early hospital readmission (75% of high-quality studies reported evidence of an association in the same direction). In evidence of moderate strength, on the basis of 2 high-quality and 3 medium-quality studies, smaller social networks were associated with longer hospital stays. When received and perceived social support were measured separately, they were not linked to health care use. Overall, the evidence did not indicate that older patients with weaker social relationships place greater demands on ambulatory care (including physician visits and community- or home-based services) than warranted by their needs.

Of the 126 articles we reviewed, 91 adjusted for health status (e.g., physical or mental health diagnosis or functional health) in multivariate analyses, 16 focused on a sample with similar health-related needs (e.g., a group of stroke patients or a population of frail older adults), and 1 was a randomized controlled trial. Our review does not therefore invalidate the message from the literature that links social relationships to worse physical and mental health outcomes,1,2,140,141 potentially increasing the burden on services. Rather, it suggests that, independently of health-related needs and with the exception of hospital readmission, there is limited evidence that social networks and support are associated with variation in health and social care utilization.

The epidemiological literature on morbidity and mortality suggests that relationships may play a greater role in shaping people’s experiences once they are ill, rather than in disease etiology.142 Stronger social networks and support are associated with higher levels of patient adherence to medical treatment,143 and individuals who perceive their relationships to be unsatisfactory are less likely to use active coping methods.144 The fact that we found comparatively consistent evidence linking social relationships to hospital readmission and length of stay (i.e., measures of volume of contact, which imply that participants are already using or have already used the service) may be a further indication of the importance of relationships for prognosis. This interpretation is consistent with the stress-buffering model of relationships and health-related outcomes, according to which relationships primarily affect outcomes among people who are under stress.7 This could explain why a majority of studies we reviewed found no evidence of association with service use, as these studies did not stratify their analyses according to health status. Future work is needed to investigate the potentially interactive effects of health and social relationships on care usage and to test whether the stress-buffering model might be a useful framework for conceptualizing the link between social relationships and service use.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the evidence on social relationships and older people’s use of health services. Our review included all settings across the care system that were studied in the research literature and was not shaped by the authors’ previous assumptions. Most of the included studies were observational, and there was considerable heterogeneity in the study populations, measurement of social relationships, and outcomes. In common with other reviews of observational studies, confounding by unmeasured common causes cannot be excluded; nor can the possibility of reverse association be eliminated, particularly in the case of senior center and day center activities, which provide older adults with the opportunity to create new relationships and reduce isolation. Observational studies were the most appropriate design for examining the association between social relationships and service utilization, but combining such data risks magnifying any bias in the individual studies. We therefore made no attempt to pool the data. We took care to select a tool for quality appraisal that was appropriate for observational studies and assessed both study design and reporting quality. We differentiated between admissions to hospital and readmissions within 30 days. This is an important measure for health services performance, but relies on accurate identification of an index admission. If readmissions were misclassified as index admissions, it is possible that we may have underestimated the impact of social relationships on readmissions.

Previous reviews of the evidence on social relationships and health have highlighted variation in effect sizes according to the social relationship domain studied. For example, in their meta-analysis of studies on mortality, Holt-Lunstad et al. found a stronger relationship with composite measures of social integration compared with binary measures of living alone.17 Although our findings also varied with the measure of social relationships (Table 1), no clear pattern emerged to suggest whether perceptions of social support, or more objective characteristics such as social network size, might be more important for service use. Aside from the studies that employed a multidimensional tool, only 5 articles included a measure of each of the 3 dimensions of relationships covered in this review11,46,76,82,129; the heterogeneity of tools they used, and the range of outcomes they assessed, may explain their conflicting findings.

Public Health Implications

Our findings are important for public health because they challenge the claim commonly voiced in the media and by campaigners and policymakers that lonely older adults are a burden on all health and social care services. In high-income countries, interventions aimed at improving the quality and quantity of older adults’ social relationships are currently being promoted as a means of preventing inappropriate service use. Our review cautions policymakers, practitioners, and researchers against assuming that reductions in care utilization can be achieved by intervening to strengthen social relationships.

Future research on social relationships would benefit from a consensus on clinically relevant concepts to measure. At present, because of the fragmented nature of the evidence, it is not clear that social relationships, independently of their implications for health and well-being, affect the service use of older people. A commitment to taking social relationships into account when one is studying service use and agreement among researchers and stakeholders on what is important to measure will enable us to build a body of work that is credible and answers important questions for designing future preventive interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

At the start of the study, B. Hanratty was supported by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Career Development Fellowship (NIHR CDF-2009-02-37, 2009 to 2013). N. K. Valtorta was initially funded from the same grant, before being awarded a NIHR Doctoral Fellowship (NIHR DRF-2013-06-074, 2013 to 2016). L. Barron was funded by the NIHR School for Primary Care Research.

Note. The NIHR had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Human participant protection was not required for this study because it did not involve human participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102(13):1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campaign to End Loneliness. Evidence about the impact of loneliness and isolation on health and social care costs. 2015. Available at: https://campaigntoendloneliness.org/guidance/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Evidence-on-health-and-social-care-costs1.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- 4.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(1):31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu F, Johnston M. Self-rated health and health service utilization: a systematic review. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(suppl 1):i180. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellaway A, Wood S, Macintyre S. Someone to talk to? The role of loneliness as a factor in the frequency of GP consultations. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(442):363–367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen S, Gottlieb B, Underwood L. Social relationships and health. In: Cohen S, Underwood L, Gottlieb B, editors. Measuring and Intervening in Social Support. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valtorta N, Hanratty B. Loneliness, isolation and the health of older adults: do we need a new research agenda? J R Soc Med. 2012;105(12):518–522. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2012.120128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almind G, Holstein BE, Holst E, Due P. Old persons’ contact with general practitioners in relation to health: a Danish population study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1991;9(4):252–258. doi: 10.3109/02813439109018528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feld S, George LK. Moderating effects of prior social resources on the hospitalizations of elders who become widowed. J Aging Health. 1994;6(3):275–295. doi: 10.1177/089826439400600301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastings SN, George LK, Fillenbaum GG, Park RS, Burchett BM, Schmader KE. Does lack of social support lead to more ED visits for older adults? Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(4):454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Jiao Z et al. Predictors of GP service use: a community survey of an elderly Australian sample. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1998;22(5):609–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molloy GJ, McGee HM, O’Neill D, Conroy RM. Loneliness and emergency and planned hospitalizations in a community sample of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(8):1538–1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Hanratty B. Loneliness, social isolation and social relationships: what are we measuring? A novel framework for classifying and comparing tools. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010799. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen RM, Davidson PL, Baumeister SE. Improving access to care. In: Kominski GF, editor. Changing the US Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services and Policy Managaement. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2014. pp. 33–69. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. York, UK: University of York; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):515–521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38740.614954.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitkala KH, Routasalo P, Kautiainen H, Tilvis RS. Effects of psychosocial group rehabilitation on health, use of health care services, and mortality of older persons suffering from loneliness: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(7):792–800. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aliyu MH, Adediran AS, Obisesan TO. Predictors of hospital admissions in the elderly: analysis of data from the longitudinal study on aging. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(12):1158–1167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alkema GE, Reyes JY, Wilber KH. Characteristics associated with home- and community-based service utilization for Medicare managed care consumers. Gerontologist. 2006;46(2):173–182. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almagro P, Barreiro B, Ochoa de Echaguen A et al. Risk factors for hospital readmission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2006;73(3):311–317. doi: 10.1159/000088092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birket-Smith M, Knudsen HC, Nissen J et al. Life events and social support in prediction of stroke outcome. Psychother Psychosom. 1989;52(1-3):146–150. doi: 10.1159/000288316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boult C, Dowd B, McCaffrey D, Boult L, Hernandez R, Krulewitch H. Screening elders for risk of hospital admission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(8):811–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callahan CM, Wolinsky FD. Hospitalization for major depression among older Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(4):M196–M202. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.4.m196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YJ, Narsavage GL. Factors related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmission in Taiwan. West J Nurs Res. 2006;28(1):105–124. doi: 10.1177/0193945905282354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chappell NL, Blandford AA. Health-service utilization by elderly persons. Can J Sociol. 1987;12(3):195–215. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho E. The effects of nonprofessional caregivers on the rehospitalization of elderly recipients in home healthcare. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2007;30(3):E1–E12. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000286625.69515.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi NG, Wodarski JS. The relationship between social support and health status of elderly people: does social support slow down physical and functional deterioration? Soc Work Res. 1996;20(1):52–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clay OJ, Roth DL, Safford MM, Sawyer PL, Allman RM. Predictors of overnight hospital admission in older African American and Caucasian Medicare beneficiaries. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(8):910–916. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coventry PA, Gemmell I, Todd CJ. Psychosocial risk factors for hospital readmission in COPD patients on early discharge services: a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Boer AG, Sprangers MA, Speelman HD, de Haes HC. Predictors of health care use in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a longitudinal study. Mov Disord. 1999;14(5):772–779. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199909)14:5<772::aid-mds1009>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dent E, Hoogendijk EO. Psychosocial factors modify the association of frailty with adverse outcomes: a prospective study of hospitalised older people. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Iorio A, Longo AL, Mitidieri Costanza A et al. Characteristics of geriatric patients related to early and late readmissions to hospital. Aging (Milano) 1998;10(4):339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF03339797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerst-Emerson K, Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: the impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):1013–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakim EA, Bakheit AM. A study of the factors which influence the length of hospital stay of stroke patients. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12(2):151–156. doi: 10.1191/026921598676265330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyduk CA. The dynamic relationship between social support and health in older adults: assessment implications. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1996;27(1-2):149–165. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krause N. Close companions at church, health, and health care use in late life. J Aging Health. 2010;22(4):434–453. doi: 10.1177/0898264309359537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Increased hospitalization risk for recently widowed older women and protective effects of social contacts. J Women Aging. 2003;15(2–3):7–28. doi: 10.1300/J074v15n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landeiro F, Leal J, Gray AM. The impact of social isolation on delayed hospital discharges of older hip fracture patients and associated costs. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(2):737–745. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee BW, Conwell Y, Shah MN, Barker WH, Delavan RL, Friedman B. Major depression and emergency medical services utilization in community-dwelling elderly persons with disabilities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1276–1282. doi: 10.1002/gps.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lesage AD, Charron M, Punti R et al. Factors related to admission of new patients consulting geriatric psychiatric services in Montreal. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1994;9(8):663–672. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Löfvenmark C, Mattiasson A-C, Billing E, Edner M. Perceived loneliness and social support in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;8(4):251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maguire PA, Taylor IC, Stout RW. Elderly patients in acute medical wards: factors predicting length of stay in hospital. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292(6530):1251–1253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6530.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCusker J, Healy E, Bellavance F, Connolly B. Predictors of repeat emergency department visits by elders. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(6):581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mistry R, Rosansky J, McGuire J, McDermott C, Jarvik L, Group UC. Social isolation predicts re-hospitalization in a group of older American veterans enrolled in the UPBEAT Program. Unified Psychogeriatric Biopsychosocial Evaluation and Treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(10):950–959. doi: 10.1002/gps.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nelms L, Johnson V, Teshuva K, Foreman P, Stanley J. Social and health factors affecting community service use by vulnerable older people. Aust Soc Work. 2009;62(4):507–524. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ottenbacher KJ, Graham JE, Ottenbacher AJ et al. Hospital readmission in persons with stroke following postacute inpatient rehabilitation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(8):875–881. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Guallar-Castillon P, Herrera MC et al. Social network as a predictor of hospital readmission and mortality among older patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12(8):621–627. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.06.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Safran DG, Graham JD, Osberg JS. Social supports as a determinant of community-based care utilization among rehabilitation patients. Health Serv Res. 1994;28(6):729–750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schenk N, Dykstra P, Maas I, van Gaalen R. Older adults’ networks and public care receipt: do partners and adult children substitute for unskilled public care? Ageing Soc. 2014;34(10):1711–1729. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Solomon DH, Wagner DR, Marenberg ME, Acampora D, Cooney LM, Jr, Inouye SK. Predictors of formal home health care use in elderly patients after hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(9):961–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stump TE, Johnson RJ, Wolinsky FD. Changes in physician utilization over time among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50(1):S45–S58. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.1.s45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilkins K, Beaudet MP. Changes in social support in relation to seniors’ use of home care. Health Rep. 2000;11(4):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Auslander GK, Soskolne V, Ben-Shahar I. Utilization of health social work services by older immigrants and veterans in Israel. Health Soc Work. 2005;30(3):241–251. doi: 10.1093/hsw/30.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bazargan M, Bazargan S, Baker RS. Emergency department utilization, hospital admissions, and physician visits among elderly African American persons. Gerontologist. 1998;38(1):25–36. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Black BS, Rabins PV, German P, McGuire M, Roca R. Need and unmet need for mental health care among elderly public housing residents. Gerontologist. 1997;37(6):717–728. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blalock SJ, Byrd JE, Hansen RA et al. Factors associated with potentially inappropriate drug utilization in a sample of rural community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2005;3(3):168–179. doi: 10.1016/s1543-5946(05)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bøen H, Dalgard OS, Johansen R, Nord E. Socio-demographic, psychosocial and health characteristics of Norwegian senior centre users: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(5):508–517. doi: 10.1177/1403494810370230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burnette D, Mui AC. In-home and community-based service utilization by three groups of elderly Hispanics: a national perspective. Soc Work Res. 1995;19(4):197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burnette D, Mui AC. Physician utilization by Hispanic elderly persons—national perspective. Med Care. 1999;37(4):362–374. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199904000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Calsyn RJ, Winter JP. Who attends senior centers? J Soc Serv Res. 1999;26(2):53–69. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng S-T. Loneliness-distress and physician utilization in well-elderly females. J Community Psychol. 1992;20(1):43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choi NG. Patterns and determinants of social service utilization: comparison of the childless elderly and elderly parents living with or apart from their children. Gerontologist. 1994;34(3):353–362. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cloutier-Fisher D, Kobayashi KM. Examining social isolation by gender and geography: conceptual and operational challenges using population health data in Canada. Gend Place Cult. 2009;16(2):181–199. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coe RM, Wolinsky FD, Miller DK, Prendergast JM. Social network relationships and use of physician services. A reexamination. Res Aging. 1984;6(2):243–256. doi: 10.1177/0164027584006002006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coe RM, Wolinsky FD, Miller DK, Prendergast JM. Complementary and compensatory functions in social network relationships among the elderly. Gerontologist. 1984;24(4):396–400. doi: 10.1093/geront/24.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coe RM, Wolinsky FD, Miller DK, Prendergast JM. Elderly persons without family support networks and use of health services. A follow-up report on social network relationships. Res Aging. 1985;7(4):617–622. doi: 10.1177/0164027585007004007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Conforti DA, Basic D, Rowland JT. Emergency department admissions, older people, functional decline, and length of stay in hospital. Australas J Ageing. 2004;23(4):189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Contrada RJ, Boulifard DA, Hekler EB et al. Psychosocial factors in heart surgery: presurgical vulnerability and postsurgical recovery. Health Psychol. 2008;27(3):309–319. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Corboy D, McLaren S, McDonald J. Predictors of support service use by rural and regional men with cancer. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(4):185–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crets S. Determinants of the use of ambulant social care by the elderly. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(12):1709–1720. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dabelko HI, Balaswamy S. Use of adult day services and home health care services by older adults: a comparative analysis. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2000;18(3):65–79. doi: 10.1300/J027v18n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eakin EG, Strycker LA. Awareness and barriers to use of cancer support and information resources by HMO patients with breast, prostate, or colon cancer: patient and provider perspectives. Psychooncology. 2001;10(2):103–113. doi: 10.1002/pon.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Forbes D, Montague P, Gibson M, Hirdes J, Clark K. Social support deficiency in home care clients. Perspectives. J Gerontol Nurs Assoc. 2011;34(3):5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Frederiks CM, te Wierik MJ, van Rossum HJ. Factors associated with differential utilization of professional care among elderly people: residents of old people’s homes compared to elderly people living at home. Acta Hosp. 1991;31(3):33–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ginsberg G, Israeli A, Cohen A, Stessman J. Factors predicting emergency room utilization in a 70-year-old population. Isr J Med Sci. 1996;32(8):649–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hand C, McColl MA, Birtwhistle R, Kotecha JA, Batchelor D, Barber KH. Social isolation in older adults who are frequent users of primary care services. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(6):e322–e324–e329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Houde SC. Predictors of elders’ and family caregivers’ use of formal home services. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21(6):533–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199812)21:6<533::aid-nur7>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iecovich E, Carmel S. Differences between users and nonusers of day care centers among frail older persons in Israel. J Appl Gerontol. 2011;30(4):443–462. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iliffe S, Kharicha K, Harari D, Swift C, Gillmann G, Stuck AE. Health risk appraisal in older people 2: the implications for clinicians and commissioners of social isolation risk in older people. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(537):277–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jackson SA, Shiferaw B, Anderson RT, Heuser MD, Hutchinson KM, Mittelmark MB. Racial differences in service utilization: the Forsyth County Aging Study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2002;13(3):320–333. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.John R, Roy LC, Dietz TL. Setting priorities in aging populations: formal service use among Mexican American female elders. J Aging Soc Policy. 1997;9(1):69–85. doi: 10.1300/J031v09n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kang SH, Bloom JR. Social support and cancer screening among older Black Americans. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(9):737–742. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.9.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim HS, Miyashita M, Harada K, Park JH, So JM, Nakamura Y. Psychological, social, and environmental factors associated with utilization of senior centers among older adults in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2012;45(4):244–250. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kobayashi KM, Cloutier-Fisher D, Roth M. Making meaningful connections: a profile of social isolation and health among older adults in small town and small city, British Columbia. J Aging Health. 2009;21(2):374–397. doi: 10.1177/0898264308329022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Krout JA, Cutler SJ, Coward RT. Correlates of senior center participation—a national analysis. Gerontologist. 1990;30(1):72–79. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lai DW. Use of home care services by elderly Chinese immigrants. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2004;23(3):41–56. doi: 10.1300/J027v23n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lai DW, Kalyniak S. Use of annual physical examinations by aging Chinese Canadians. J Aging Health. 2005;17(5):573–591. doi: 10.1177/0898264305279778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lai DWL. Predictors of use of senior centers by elderly Chinese immigrants in Canada. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work. 2006;15(1-2):97–121. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lam BT, Cervantes AR, Lee WK. Late-life depression, social support, instrumental activities of daily living, and utilization of in- home and community-based services in older adults. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2014;24(4):499–512. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Larsson K, Thorslund M, Forsell Y. Dementia and depressive symptoms as predictors of home help utilization among the oldest old: population-based study in an urban area of Sweden. J Aging Health. 2004;16(5):641–668. doi: 10.1177/0898264304268586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.LaVeist TA, Sellers RM, Brown KA, Nickerson KJ. Extreme social isolation, use of community-based senior support services, and mortality among African American elderly women. Am J Community Psychol. 1997;25(5):721–732. doi: 10.1023/a:1024643118894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li LW. Caregiving network compositions and use of supportive services by community-dwelling dependent elders. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2004;43(2-3):147–164. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Litwin H. Support network type and health service utilization. Res Aging. 1997;19(3):274–299. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Longman JM, I Rolfe M, Passey MD et al. Frequent hospital admission of older people with chronic disease: a cross-sectional survey with telephone follow-up and data linkage. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):373. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lorén Guerrero L, Gascón Catalán M. Biopsychosocial factors related to the length of hospital stay in older people. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2011;19(6):1377–1384. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692011000600014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Malasi TH, Mirza IA, el-Islam MF. Factors influencing long-term psychiatric hospitalisation of the elderly in Kuwait. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1989;35(3):223–230. doi: 10.1177/002076408903500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McAuley WJ, Arling G. Use of in-home care by very old-people. J Health Soc Behav. 1984;25(1):54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mechakra-Tahiri SD, Zunzunegui MV, Dube M, Preville M. Associations of social relationships with consultation for symptoms of depression: a community study of depression in older men and women in Quebec. Psychol Rep. 2011;108(2):537–552. doi: 10.2466/02.13.15.PR0.108.2.537-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Miltiades HB, Wu B. Factors affecting physician visits in Chinese and Chinese immigrant samples. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(3):704–714. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miner S. Racial differences in family support and formal service utilization among older persons: a nonrecursive model. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50(3):S143–S153. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.3.s143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nägga K, Dong HJ, Marcusson J, Skoglund SO, Wressle E. Health-related factors associated with hospitalization for old people: comparisons of elderly aged 85 in a population cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(2):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Naughton C, Drennan J, Treacy P et al. The role of health and non-health-related factors in repeat emergency department visits in an elderly urban population. Emerg Med J. 2010;27(9):683–687. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.077917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Naughton C, Drennan J, Treacy P et al. How different are older people discharged from emergency departments compared with those admitted to hospital? Eur J Emerg Med. 2011;18(1):19–24. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32833943d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nelson MA. Race, gender, and the effects of social supports on the use of health services by elderly individuals. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1993;37(3):227–246. doi: 10.2190/TH88-1W6U-B0AT-377U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nelson T, Fernandez JL, Livingston G, Knapp M, Katona C. Does diagnosis determine delivery? The Islington study of older people’s needs and health care costs. Psychol Med. 2004;34(1):147–155. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Newall N, McArthur J, Menec VH. A longitudinal examination of social participation, loneliness and use of physician and hospital services. J Aging Health. 2015;27(3):500–518. doi: 10.1177/0898264314552420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Parboosingh EJ, Larsen DE. Factors influencing frequency and appropriateness of utilization of the emergency room by the elderly. Med Care. 1987;25(12):1139–1147. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198712000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Penning MJ. Health, social support, and the utilization of health services among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50(5):S330–S339. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.5.s330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Préville M, Vasiliadis HM, Boyer R et al. Use of health services for psychological distress symptoms among community-dwelling older adults. Can J Aging. 2009;28(1):51–61. doi: 10.1017/S0714980809090011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Redondo-Sendino Á, Guallar-Castillón P, Banegas JR, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Gender differences in the utilization of health-care services among the older adult population of Spain. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rennemark M, Holst G, Fagerstrom C, Halling A. Factors related to frequent usage of the primary healthcare services in old age: findings from The Swedish National Study on Aging and Care. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17(3):301–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rittner B, Kirk AB. Health care and public transportation use by poor and frail elderly people. Soc Work. 1995;40(3):365–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Simning A, Van Wijngaarden E, Fisher SG, Richardson TM, Conwell Y. Mental healthcare need and service utilization in older adults living in public housing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(5):441–451. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31822003a7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Smith GC. Patterns and predictors of service use and unmet needs among aging families of adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(6):871–877. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Starrett RA, Decker JT, Araujo A, Walters G. The Cuban elderly and their service use. J Appl Gerontol. 1989;8(1):69–85. doi: 10.1177/073346488900800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Starrett RA, Todd AM, DeLeon L. A comparison of the social service utilization behavior of the Cuban and Puerto Rican elderly. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1989;11(4):341–353. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Starrett RA, Bresler C, Decker JT, Walters GT, Rogers D. The role of environmental awareness and support networks in Hispanic elderly persons’ use of formal social services. J Community Psychol. 1990;18(3):218–227. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stoddart H, Whitley E, Harvey I, Sharp D. What determines the use of home care services by elderly people? Health Soc Care Community. 2002;10(5):348–360. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tennstedt SL, Crawford S, McKinlay JB. Determining the pattern of community care: is coresidence more important than caregiver relationship? J Gerontol. 1993;48(2):S74–S83. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.2.s74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Thambypillai V. Utilization of formal social support services by non-institutionalized ill elderly. Singapore Med J. 1986;27(4):281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tomassini C, Glaser K, Stuchbury R. Family disruption and support in later life: a comparative study between the United Kingdom and Italy. J Soc Issues. 2007;63(4):845–863. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tran TV, Dhooper SS, McInnis-Dittrich K. Utilization of community-based social and health services among foreign born Hispanic American elderly. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1997;28(4):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Walter-Ginzburg A, Chetrit A, Medina C, Blumstein T, Gindin J, Modan B. Physician visits, emergency room utilization, and overnight hospitalization in the old-old in Israel: The Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Aging Study (CALAS) J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):549–556. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wan TT. Functionally disabled elderly. Health status, social support, and use of health services. Res Aging. 1987;9(1):61–78. doi: 10.1177/0164027587009001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wolinsky FD, Johnson RJ. The use of health services by older adults. J Gerontol. 1991;46(6):S345–S357. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.6.s345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wong FK, Chan MF, Chow S et al. What accounts for hospital readmission? J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(23-24):3334–3346. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Auslander GK, Soffer M, Auslander BA. The supportive community: help seeking and service use among elderly people in Jerusalem. Soc Work Res. 2003;27(4):209–221. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Barresi CM, McConnell DJ. Adult day care participation among impaired elderly. J Fam Econ Iss. 1987;8(3-4):82–94. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Chappell NL. Social support and the receipt of home care services. Gerontologist. 1985;25(1):47–54. doi: 10.1093/geront/25.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cohen CI, Magai C, Yaffee R, Walcott-Brown L. Comparison of users and non-users of mental health services among depressed older, urban African Americans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(7):545–553. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.7.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Eustace A, Denihan A, Bruce I, Cunningham C, Coakley D, Lawlor BA. Depression in the community dwelling elderly: do clinical and sociodemographic factors influence referral to psychiatry? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(10):975–979. doi: 10.1002/gps.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Greysen SR, Horwitz LI, Covinsky KE, Gordon K, Ohl ME, Justice AC. Does social isolation predict hospitalization and mortality among HIV+ and uninfected older veterans? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1456–1463. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Iecovich E, Biderman A. Attendance in adult day care centers and its relation to loneliness among frail older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(3):439–448. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Jordan RE, Hawker JI, Ayres JG et al. Effect of social factors on winter hospital admission for respiratory disease: a case–control study of older people in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(551):400–402. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X302682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kempen GI, Suurmeijer TP. Factors influencing professional home care utilization among the elderly. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(1):77–81. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ralston PA. Senior center utilization by Black elderly adults: social, attitudinal and knowledge correlates. J Gerontol. 1984;39(2):224–229. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.West GE, Delisle MA, Simard C, Drouin D. Leisure activities and service knowledge and use among the rural elderly. J Aging Health. 1996;8(2):254–279. doi: 10.1177/089826439600800206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Oude Voshaar RC et al. Social relationships and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;22:39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Zuidema SU et al. Social relationships and cognitive decline: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(4):1169–1206. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Berkman LF, Krishna A. Social network epidemiology. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 235–289. [Google Scholar]

- 143.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Steptoe A, Owen N, Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Brydon L. Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(5):593–611. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]