In a spring 2017 lecture at the University of Maryland, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, described pandemic influenza as what keeps him awake at night. Today, the possibility of a novel influenza virus with a high attack rate remains one of public health’s greatest concerns.

Even without a pandemic, Iuliano et al. recently estimated that influenza kills 291 000 to 646 000 people globally in a year.1 In the United States, during an average flu season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates the disease burden to range between 9.2 and 60.8 million cases annually, with between 140 000 and 710 000 adults hospitalized with influenza-related complications (http://bit.ly/2hr9YbP). Influenza-related mortality is responsible for 12 000 to 56 000 deaths per year, the majority (64%) among adults aged 65 years and older, with higher age-adjusted influenza mortality rates for African Americans than for Whites.2 Although the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends annual immunization against influenza for all adults, with a Healthy People 2020 goal of 70% uptake, significant disparities by race, ethnicity, and income exist today, causing unnecessary illness and death.3,4

WORRISOME DISPARITIES

Disparities extend to uptake of pneumococcal vaccination, with the percentage of adults aged 65 years and older by race and ethnicity who have ever received a pneumococcal vaccination at 47.8% for Hispanics, 55.2% for Blacks, and 71.0% for Whites.5 Of the three groups, White adults were more likely to have ever received a pneumococcal vaccination than Black and Hispanic adults.5

There is no question that worrisome disparities in flu and pneumococcal vaccination rates persist over time, yet there has been limited research to examine this at the neighborhood level. However, the welcome news is that there is increasing interest in the social determinants of influenza and vaccination that will enable researchers to move beyond individual attitudes and behaviors and explore neighborhood and community characteristics, workplace and social policies, and systemic factors.

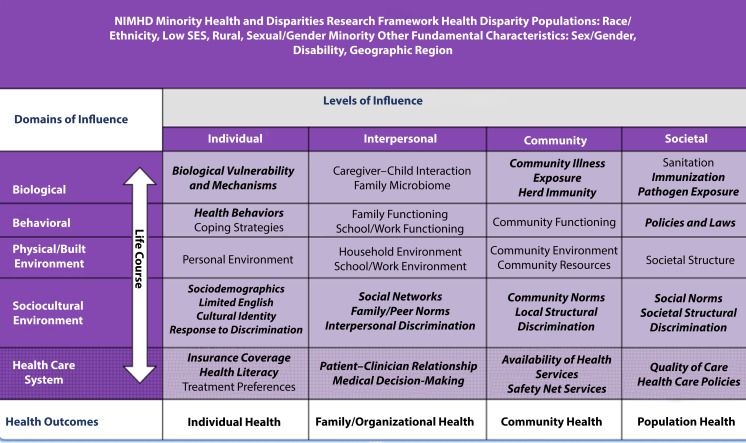

Early in 2017, the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities released its Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework, calling on researchers to investigate health disparities through examining complex interactions among individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels with specific domains from biological, behavioral, physical or built environment, sociocultural environment, and health care systems (http://bit.ly/2DZB0Fb). This framework (Figure 1) can inform research on influenza and pneumococcal vaccination disparities, providing a depth of understanding that is often missing from the literature.

FIGURE 1—

Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework

Note. NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; SES = socioeconomic status. Factors that are relevant to vaccination are bolded and italicized.

Source. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (http://bit.ly/2DZB0Fb).

In this issue of AJPH, the article by Hughes et al. (p. 517) is unique in that it provides an opportunity to look at local neighborhood vaccination rates. One of the interesting facets of the study was their ability to examine differences between Hispanic populations, comparing Puerto Ricans to Mexicans in Chicago, Illinois; too frequently, other research fails to explore within-group differences that can be meaningful. The authors found distinct differences in several areas including lack of awareness of vaccine recommendations, perceived disease risk and vaccine safety concerns, vaccine receipt, the impact of insurance status, and acculturation. Acculturation emerged as an interesting variable with increasing acculturation associated with decreasing flu vaccination. Although much of the literature on adult vaccine disparities has focused thus far on African Americans, there is emerging scholarship that examines the barriers to immunization, including health care access and lack of insurance, acculturation, country of nativity, and immigration status. The findings presented here for the two largest Hispanic groups speaks to the importance of “breaking down the monolith” to understand within-group differences, which will ultimately contribute to the ability to more effectively target and tailor interventions.

NUANCED DIFFERENCES

I applaud the authors’ example of two distinct Hispanic subgroups and different neighborhoods. In future research, I would argue that a more nuanced study of differences between Hispanics, and indeed between neighborhoods, could foster a more complete understanding of living and working environments. During the H1N1 pandemic, our research included the first empirical test of the conceptual model by Blumenshine et al. of disparities in a pandemic, which examined disparities in exposure, susceptibility to complications, and access to care.6 Our research demonstrated that Hispanic adults—English-speaking but particularly Spanish-speaking Hispanics—were much more likely to be exposed to influenza, because, in part, of housing factors including living in an apartment building, having a larger household size, and having less access to care. Indeed, our research team estimated that, combined with undervaccination, this resulted in 1.2 million additional cases of H1N1 among Hispanics.7 This Chicago study and our previous work points to the importance of research at the community, neighborhood, and societal levels, and recognizing how the complex interactions of factors can differentially affect subpopulations.

Interestingly, the study’s primary results focus more on intrapersonal factors such as trust, perceived risk, and concerns about vaccine safety, and less so on the impact of access to care, which clearly emerged as more important in the context of pneumococcal vaccination. These results are important for tailoring health communication about these vaccines. In future research, there may be an opportunity to explore other potential differences within and between these neighborhoods that could have an impact on vaccine uptake, including prevalence of chronic health conditions in these neighborhoods. Given what we know about racial, ethnic, and income disparities in chronic conditions and the recommendation that populations at high risk receive an annual flu vaccination, the potential inclusion of this issue in future research would reflect the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities framework’s biological domain, individual biological vulnerability and mechanisms, and specific facets of the health care domain. The authors’ finding that access to health care was associated with pneumococcal vaccination rates is an important one. In addition to identifying insurance and actual health care facilities, future research could include whether patients received a recommendation and an offer of the vaccine at their provider visit, thereby bridging the interaction between interpersonal interactions and the health care domain.

MULTILEVEL INTERVENTIONS

This study provides a stimulus for other localities to consider local-level research on vaccination disparities. However, to fully realize the potential for changes in local public health and health care practices and policies, future studies, explicitly focused on adult vaccination, would benefit from an in-depth examination of intrapersonal, interpersonal, community, and societal factors that influence vaccine decision-making. When research can reflect the complex interaction of the multiple drivers of disparities, public health agencies, health care providers, community organizations, and policymakers will have the data to pursue the types of multilevel interventions necessary to eliminate disparities in vaccine uptake.

Footnotes

See also Hughes et al., p. 517.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iuliano AD, Roguski K, Chang H et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Jiaquan X, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(4):1–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2017–18 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2017;66(2):1–20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6602a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. Healthy People 2020: Immunization and infectious disease. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke TC, Norris T, Schiller JS. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2016 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/earlyrelease201705.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2017.

- 6.Quinn SC, Kumar S, Freimuth VS, Musa D, Casteneda-Angarita N, Kidwell K. Racial disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and access to health care in the US H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):285–293. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar S, Quinn SC, Kim KH, Daniel LH, Freimuth VS. The impact of workplace policies and other social factors on self-reported influenza-like illness incidence during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):134–140. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]