Abstract

Background

A growing body of research has examined transgender identity development, but no studies have investigated developmental pathways as a transactional process between youth and caregivers, incorporating perspectives from multiple family members. The aim of this study was to conceptualize pathways of transgender identity development using narratives from both transgender and gender nonconforming (TGN) youth and their cisgender (non-transgender) caregivers.

Methods

The sample included 16 families, with 16 TGN youth, ages 7–18 years, and 29 cisgender caregivers (N = 45 family members). TGN youth represented multiple gender identities, including trans boy (n = 9), trans girl (n = 5), gender fluid boy (n = 1), and girlish boy (n = 1). Caregivers included mothers (n = 17), fathers (n = 11), and one grandmother. Participants were recruited from LGBTQ community organizations and support networks for families with transgender youth in the Midwest, Northeast, and South regions of the United States. Each family member completed a one-time in-person semi-structured qualitative interview that included questions about transgender identity development.

Results

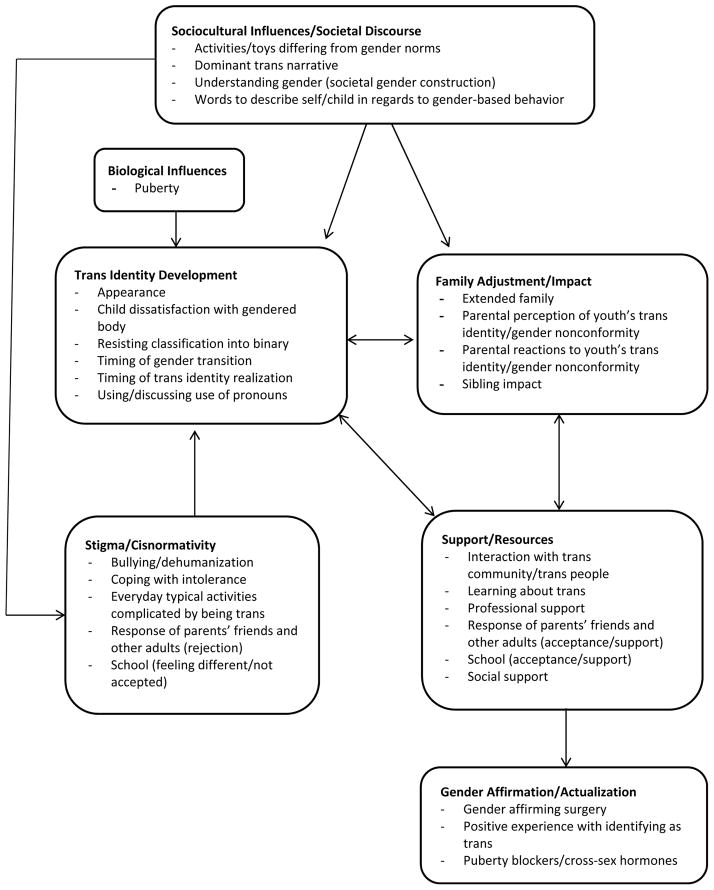

Analyses revealed seven overarching themes of transgender identity development, which were organized into a conceptual model: Trans identity development, sociocultural influences/societal discourse, biological influences, family adjustment/impact, stigma/cisnormativity, support/resources, and gender affirmation/actualization.

Conclusions

Findings underscore the importance of assessing developmental processes among TGN youth as transactional, impacting both youth and their caregivers.

Keywords: family dynamics, gender identity, identity development, parent-child relationships, transgender youth

Transgender individuals, who have a gender identity and/or gender expression that does not match their sex assigned at birth, have become a more visible part of U.S. society, receiving growing media and political attention. Visibility has also increased in the research community, with recent studies reporting a 10- to 100-fold increase in transgender population size estimates (Deutsch, 2016). Although there is an increase in awareness and discourse around transgender issues, those individuals who deviate from traditional gender norms are often still subject to discrimination, prejudice, and stigma (Adams et al., 2016; Clements-Nolle, Marx & Katz, 2006; Grant et al., 2011; Kattari et al., 2015; Wyss, 2004). Minority stress theory proposes that experiencing prejudice and discrimination related to stigma associated with holding a marginalized identity has a negative impact on health (Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Meyer, 2003). As a likely consequence to minority stress experienced as a result of stigma associated with being transgender, studies of mental health among transgender individuals, including youth, consistently show elevated rates of suicidality, anxiety, and depression (Bouman et al., 2017; Colizzi, Costa, & Todarello, 2014; Connolly, Zervos, Barone, Johnson, & Joseph, 2016; Millet, Longworth, & Arcelus, 2017; Perez-Brumer, Hatzenbuehler, Oldenburg, & Bockting, 2015; Reisner et al., 2015; Tebbe & Moradi, 2016; Warren, Bryant Smalley, & Nikki Barefoot, 2016). Mental and physical health care professionals have begun to see a substantial rise in referrals for gender nonconforming youth (Malpas, 2011; Meyer, 2012; Alegria, 2011; Olson-Kennedy, 2016). Despite the considerable demand for services and rights on a national level, there is relatively little known about the identity development of transgender individuals, and even less known about developmental pathways among transgender youth in transaction with their family and social environment. This study, therefore, aimed to conceptualize transgender identity developmental pathways from the perspectives of transgender and gender nonconforming (TGN) youths and their caregivers.

Gender Identity Development

Gender is a fundamental part of human identity and one’s gender assignment has significant psychosocial implications throughout life (Egan & Perry, 2001). The majority of theories of gender identity focus on development in childhood (Martin, Ruble, & Szkrybalo, 2002). Kohlberg’s (1966) classic stage theory of gender development proposed that children are able to correctly identify their gender by two years of age, understand that their gender remains stable across time by four years of age, and understand their gender to be constant and independent of external features by seven years of age. The context in which gender identity forms includes a multitude of competing discourses and role expectations (Abrams, 2003).

Gender identity is a multidimensional construct that includes an individual’s knowledge of belonging in a gender category, experienced compatibility with that particular category, felt pressure to conform, and attitudes towards gender groups (Egan & Perry, 2001). Children and adolescents are often left to negotiate the pressures to conform to their assigned gender group (Brinkman, Rabenstein, Rosen, and Zimmerman, 2014). Gender nonconformity and violations of social role expectations, then, may lead to victimization and discrimination (Lombardi, Wilchins, Priesing, & Moulof, 2001).

Transgender Identity Development

Qualitative research has described transgender identity development in adults as a series of developmental stages (Bockting, 2014; Devor, 2004; Lewins, 1995). Bockting and Coleman (2007) based their stage model for transgender identity development on a coming-out model previously used to describe lesbian and gay individuals. Devor (2004) put forth a transsexual identity development model characterized by 14 stages, beginning with anxiety (Stage 1: Abiding anxiety) and confusion (Stage 2: Identity confusion about originally assigned gender and sex) and ending with identity integration (Stage 13) and pride (Stage 14). Hiestand and Levitt (2005) developed a 7-stage model of gender identity development among butch lesbian women that similarly began with distress (Stage 1: Gender conflict) and ended with pride (Stage 6: Gender affirmation and pride) and identity integration (Stage 7: Integration of sexual orientation and gender difference). A limitation of many of the known transgender identity developmental theories is that they are either based on models of coming out as lesbian/gay or integrate transgender identity and sexual orientation development into the same model. Few theories focus solely on transgender identity development.

In another study of transgender identity development, Morgan and Stevens (2012) interviewed six transgender adults and analyzed data from a lifespan perspective, yielding three prominent themes: an early sense of body-mind dissonance, managing and negotiating identities, and the process of transition. However, the concept of transition is complicated by the fact that many transgender individuals use non-binary identities, such as genderqueer, and choose not to take hormones or undergo gender affirming surgeries (Kuper, Nussbaum, & Mustanski, 2012). Although many pre-existing models of transgender identity development propose that early stages of transgender identity development occur during childhood (e.g., Bockting & Coleman, 2007; Morgan & Stevens, 2012), to our knowledge, there are no stage models of development based off the perspectives of trans youth, and no models that include perspectives from both caregivers and trans youth.

Recently, researchers have begun to consider the experiences of transgender youth in conceptualizations of transgender identity development. Olson et al. (2015) investigated whether 32 pre-pubescent children who were presenting per their gender identity would show patterns of cognition more consistent with their expressed gender or their natal sex. In this cross-sectional study, researchers found that TGN youth were statistically indistinguishable from cisgender (non-transgender) controls of the same gender on an implicit bias test. Specifically, Olson et al. found that TGN youth showed clear patterns of viewing themselves in terms of their expressed gender and showed preferences for their expressed gender that mirrored the response patterns of same-gender cisgender controls. This research suggests that TGN youths’ gender identity is similar to that of same-gender cisgender youth.

A common limitation of previous models and research on transgender identity development is the exclusion of gender nonconforming individuals, including those with non-binary gender identities (Rahilly, 2015). Another limitation is that the existing body of research is based primarily on the experiences of transgender individuals with a White race/ethnicity (Moradi et al., 2016); little is known about transgender identity development among transgender individuals of color. Transgender identity development not only occurs in relation to one’s authentic self, but also in relation to one’s social sphere (Levitt & Ippolito, 2014). Although researchers have explored conceptualizations beyond stage theories and have begun to incorporate TGN youths’ perspectives (Olson et al., 2015), there is still a need for more studies of transgender identity development that incorporate perspectives from both TGN youth and their families.

Family Perspective

Family systems theory proposes that a transition for one family member affects the entire family system (Cox & Paley, 1997; Minuchin, 1985). In families with transgender youth, the process of youth forming a transgender identity and transitioning to their affirmed gender affects all family members. In a sense, families with transgender youth are all transitioning. Recently, research on transgender youth has expanded to the family, particularly focusing on parents and caregivers (Dierckx, Motmans, Mortelmans, & T’sjoen, 2016; Rahilly, 2015; Sansfacon, Robichaud, & Dumais-Michaud, 2015). As for all youth, caregivers are understood to significantly impact the well-being of transgender youth (McConnell, Birkett, & Mustanski, 2016; Ryan, Russell, Hhuebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010). A qualitative study of resiliency among transgender youth found that participants described their families as a primary source of resilience (Singh, Meng, & Hansen, 2014). Although caregivers may initially experience surprise related to their child’s transgender identity, research suggests that caregivers often adjust to having a transgender child as their awareness of the needs of their child increases (Riley, Sitharthan, Clemson, & Diamond, 2011). Gender expression is often overseen and managed by caregivers (e.g., clothing purchases, haircuts), thus caregivers play a large role in potentially reducing the distress that transgender youth may experience by allowing their children to socially transition (Ehrensaft, 2012).

Existing literature on familial adjustment to transgender youths’ gender transitioning is based primarily on clinical samples (Rosenberg, 2002; Wren, 2002). Lev and Alie (2012) developed a stage model for therapeutic work with caregivers and gender nonconforming youth, which included the following stages: 1) learning of the child’s gender nonconformity; 2) confusion experienced among family members; 3) negotiating adjustments to be made within the family; and 4) finding balance, which occurs once the child is accepted and integrated back into the family as their authentic self. Caregivers of transgender youth often struggle between accepting their child and negotiating social stigma attached to gender nonconformity (Dierckx, et al., 2016; Di Cegile & Thummel, 2006; Kuvalanka, Weiner, & Mahan, 2014).

Caregivers who were raised in the United States or Canada have likely internalized the cultural ideology that assigned sex determines gender and that gender is binary (Rahilly, 2015; Sansfacon et al., 2015), although it should be noted that these ideologies may differ across race/ethnicities. Rahilly (2015) conducted a longitudinal study of 24 caregivers who represented 16 gender nonconforming youth and found three salient themes that centered on challenging the gender binary. The first major practice that emerged was what Rahilly (2015) referred to as “gender hedging,” or caregivers attempting to set boundaries around their child’s gender atypical behaviors to find neutral ground that both satisfies their child’s preferences and meets societal gender expectations (e.g., caregiver purchasing pink socks, but not a dress for their child who is male assigned at birth and gender nonconforming). This maneuvering within the binary was often out of protection for their children and resulted in caregivers experiencing criticism of the current construction of gender. Caregivers described a second practice of resisting the gender binary by learning more inclusive definitions of gender and affirming their child’s identity as a natural part of human diversity. Finally, caregivers assessed when to “play along” with the gender binary and when to disrupt other peoples’ assumptions of gender and sex (Rahilly, 2015). Although stigma associated with gender variance presents challenges for transgender youth and their families, research suggests that resources, support, and affirmation might mitigate psychological risks that can result from oppression (Hill, Menvielle, Sica, & Johnson, 2010; Olson, Durwood, DeMeules, & McLaughlin, 2016).

The Availability of Resources

Levitt and Ippolito (2014) describe transgender identity development as a process of balancing the desire to be one’s true self with considerations of consequences to transition, coping skills, and available resources. For both caregivers and transgender youth, contact with others in the community or with other families with transgender children can be protective and critical to finding support and information (Kuvalanka et al., 2014; Testa, Jimenez, & Rankin, 2014). Wren (2002) found in interviews with caregivers of gender-variant adolescents that the caregivers’ understanding of the concept of (trans)gender was strongly related to their acceptance. It is well-established that children whose gender identity is affirmed tend to have better mental health (Connolly et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2010) and transgender children who socially transition have similar levels of depression compared to cisgender controls, although they have slightly higher levels of anxiety (Olson et al., 2016). Transition is generally understood to be a family-level process and family members may experience a range of emotions when someone they love transitions. A supportive environment is a necessary pre-requisite to adjustment and acceptance of a transgender family member (Dierckx et al., 2016). Although many caregivers need support in coping with stigma and in advocating for their gender nonconforming child (Riley et al., 2011), there continues to be a lack of policy protection, trans-positive services, and overall access to affirmative healthcare (Gridley et al., 2016; Minter & Kriesling, 2010), particularly for transgender individuals who also have low income or are people of color.

The Current Study

As the field recognizes that transgender identity development does not occur in isolation, more studies have focused on the role of caregivers, family members, and the broader community (Di Cegile & Thummel, 2006; Dierckx et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2010; Kuvalanka et al., 2014). However, the majority of existing research includes small samples of either transgender adults or caregivers of transgender youth. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to integrate both TGN youth and caregiver perspectives in a conceptualization of transgender identity developmental pathways.

Method

Participants

Participants included 16 families, with 16 TGN youth, ages 7–18 years (M = 12.55, SD = 3.86), and 29 cisgender caregivers (N = 45). Youth self-identified their current gender identity as trans boy (n = 9), trans girl (n = 5), gender fluid boy (n = 1), and girlish boy (n = 1). Caregivers included mothers (n = 17), fathers (n = 11), and one grandmother. Other sample demographics are reported in Table 1. Participants were recruited from LGBTQ community organizations and support networks for families with transgender youth in the following U.S. regions: Midwest, Northeast, and South. Snowball sampling was also utilized. Eligibility criteria for youth included being age 5–18 years, identifying with a different gender from their assigned sex at birth (e.g., transgender, trans) or being gender nonconforming, and having at least one caregiver who was willing to participate. Eligibility for caregivers included having a youth who met the above criteria and was willing to participate. Volunteers were asked to participate in a study about the experiences of families with transgender youth, including emotional and identity-related experiences.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics for Transgender Youth and Caregivers from the Trans Youth Family Study

| Measure | Youth (N = 16) | Caregivers (N = 29) | Families (N = 16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M (SD) | 12.55 (3.86) | 47.45 (7.06) | |

| Sex assigned at birth, % (n) | |||

| Female | 56.3 (9) | 62.1 (18) | |

| Male | 43.8 (7) | 37.9 (11) | |

| Current gender identity, % (n) | |||

| Cisgender woman | 62.1 (18) | ||

| Cisgender man | 37.9 (11) | ||

| Trans girl/girl | 31.3 (5) | ||

| Trans boy/boy | 56.3 (9) | ||

| Other | 12.5 (2) | ||

| Race/ethnicity, % (n) | |||

| White | 87.5 (14) | 75.9 (22) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3.4 (1) | ||

| Multiracial/other | 12.5 (2) | 20.7 (6) | |

| Education, % (n) | |||

| High school diploma/GED | 3.4 (1) | ||

| Some college | 6.9 (2) | ||

| College degree | 48.3 (14) | ||

| Graduate degree | 41.4 (12) | ||

| Individual income, % (n) | |||

| $10,000–30,000 | 10.3 (3) | ||

| $30,001–60,000 | 24.1 (7) | ||

| $60,001–100,000 | 24.1 (7) | ||

| ≥ $100,001 | 37.9 (11) | ||

| Retired | 3.4 (1) | ||

| County of origin, % (n) | |||

| U.S. | 89.7 (26) | ||

| Non-U.S. | 10.3 (3) | ||

| Current geographic location, % (n) | |||

| Midwest | 12.5 (2) | ||

| Northeast | 81.3 (13) | ||

| South | 6.3 (1) | ||

| Sexual orientation, % (n) | |||

| Heterosexual/straight | 31.3 (5) | 82.8 (24) | |

| Bisexual | 12.5 (2) | 6.9 (2) | |

| Lesbian/gay | 6.3 (1) | 6.9 (2) | |

| Pansexual | 6.3 91) | ||

| Unsure | 43.8 (7) | ||

| Other | 3.4 (1) | ||

| Relationship status, % (n) | |||

| Single | 3.4 (1) | ||

| Married | 79.3 (23) | ||

| Living with partner (unmarried) | 6.9 (2) | ||

| Separated/divorced | 10.3 (3) | ||

| Widowed | 3.4 (1) | ||

Notes. Caregiver age range: 34–63 years. Youth age range: 7–18 years. All cisgender men were fathers. 17 out of 18 cisgender women were mothers; 1 was a grandmother. Other gender identities included gender-variant and “girlish boy.” Frequencies for languages used at home, religion practiced at home, and relationship status were overlapping because participants could choose or write in more than one option.

Researchers

The authors were all involved in this project in some form and represent a diversity of life experiences that informed this work. Although it cannot be assumed that shared identities correlate with a greater understanding and richness of analyses, we describe our relevant identities below to better position ourselves in relation to this study. Katz-Wise is a White queer (non-heterosexual) cisgender woman researcher and professor who is trained in developmental psychology, gender and women’s studies, and social epidemiology and has expertise in research with transgender youth and families. Budge is a White queer (non-heterosexual) cisgender woman professor of counseling psychology with expertise in research with transgender populations. Katz-Wise and Budge are co-Principal Investigators of this study. Fugate is a White heterosexual cisgender woman who has experience working with children and adolescents as a teacher, coach, researcher, and public health professional. Flanagan is a White queer cisgender woman who is trained in clinical psychology, with an emphasis in LGBTQ veteran health. Touloumtzis is a heterosexual cisgender woman who has worked with adolescents as a researcher. Rood is a mixed race gay cisgender man, professor of psychology, with expertise in LGBTQ health. Perez-Brumer is Latina cisgender woman. Finally, Leibowitz is a White, gay, cisgender man who is a child and adolescent psychiatrist specializing in transgender and gender diverse youth and their families in multidisciplinary settings. Flanagan, Rood, and Perez-Brumer were interviewers for the project and Leibowitz was a co-Investigator. Fugate, Flanagan, and Touloumtzis completed the data analysis, which was overseen by Katz-Wise, and audited by Budge. Other members of the research team who assisted in conducting and transcribing interviews were graduate students in counseling psychology, clinical psychology, public health, and human development.

When we began this analysis, we held a number of assumptions. First, we held the assumption that, although we expected to find common themes regarding the process of transgender identity development, this process will likely look different across participants, particularly between participants of different ages and gender identities. Since many of the participants in this study were younger and already identifying as TGN, we expected both transgender youth and caregivers to describe experiences of transgender identity development from early in the youths’ childhood. Second, we held the assumption that stigma related to being transgender on both an interpersonal and societal level would shape transgender youths’ and caregivers’ perceptions of and experiences of transgender identity development. Third, we held the assumption that the majority of caregivers in the study would be at least somewhat supportive of their TGN child, since they agreed to participate in this study as a family. This assumption was not met for all caregiver participants. At least one caregiver in this study described that they were struggling to be supportive; however, this was not the norm for most families. In addition to support, we anticipated that caregivers may have complex feelings about their child’s gender identity related to concerns for safety and well-being. We also anticipated that the transgender youth and caregivers may describe experiences of both support and rejection from people outside of the immediate family (e.g., extended family members, peers at school) that may influence transgender identity development. Finally, we held the assumption that families from the Northeast may experience more support from the community for their child’s gender identity than families from the Midwest or South regions of the United States.

Our assumptions regarding expectations for study results were likely shaped in part by our own experiences. Of note, all the authors – and particularly those who conducted the analysis – are cisgender and none of us are caregivers. Therefore, we are interpreting the experiences of TGN youth and caregivers through an outsider lens, which may have hindered our ability to accurately understand the experiences of families with transgender youth. Because of this, there may be themes that we did not identify – or may have identified differently – due to a lack of direct experience either forming a transgender identity ourselves or being a caregiver of a youth who is undergoing this process. However, many of us have conducted numerous research studies in this area and/or have substantial clinical experience with this population, as well as personal experience with friends and colleagues who identify as transgender. We hope that our experience and centering of participants’ voices in this study has allowed us to accurately represent the experiences of TGN youth and caregivers, to the best of our ability.

Interview Protocol

Semi-structured interview protocols were developed for the current study. Separate protocols were developed for TGN youth and caregivers, but included similar questions. Two protocols were developed for TGN youth, which were developmentally appropriate for youth age 5–11 years and age 12–18 years. Developmental appropriateness of the protocols was determined in consultation with Leibowitz, who has substantial clinical experience with children. Interview questions analyzed for this study addressed assigned sex at birth; current gender identity; and transgender identity development, including developmental milestones (e.g., age youth first identified their gender differently than their sex assigned at birth, age youth first told someone about gender identity), perceptions of gender identity by TGN youth and others, and interactions with other transgender individuals. Other interview questions not analyzed for this study addressed emotions and coping related to the youth’s gender identity, effects of the youth’s gender identity on relationships within and outside of the family, and support needs, and have been published elsewhere (Katz-Wise, Budge, Orovecz, Nguyen, Nava-Coulter, & Thomson, 2017).

Procedure

Two-hour sessions consisting of one-on-one in-person semi-structured interviews and surveys with TGN youth and caregivers were conducted between April and October 2013 in participants’ homes or at the researchers’ institutions. Each participant gave written informed assent/consent prior to participating, and then completed an interview and paper survey in a private room with an interviewer. Interviews typically lasted between 30 and 90 minutes, and surveys lasted between 15 and 30 minutes. Interviews were digitally recorded and audio files were transcribed verbatim by graduate students from the researchers’ institutions. Due to funding constraints, participants were not offered an incentive for participation; however, all participants were given a comprehensive resource list at the end of the study session. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at each study site.

Analytic Methodology

We used an immersion/crystallization (Borkan, 1999) and template organizing style (Crabtree & Miller, 1999) approach to organizing and analyzing data from interview transcripts. Coding and analysis of interview transcripts were completed by Fugate, Flanagan, and Touloumtzis using the mixed methods program Dedoose for data management. Katz-Wise trained the three coders and oversaw all data analyses. First, Fugate and Touloumtzis developed a codebook based on a subset of eight interview transcripts: two trans girls (age 8 and 15 years), two trans boys (age 9 and 17 years), two mothers (one of a trans girl age 14 years, one of a trans boy age 10 years), and two fathers (one of a trans boy age 17 years, one of a girlish boy age 18 years). One codebook was developed for both TGN youth and caregivers. Then the codebook underwent a review process with Flanagan and Katz-Wise, in which multiple drafts of the codebook were reviewed and revised, to clarify any codes and code definitions that were unclear. Then Fugate, Flanagan, and Touloumtzis coded a subset of interview excerpts in Dedoose to establish interrater reliability and met to discuss the coding process to ensure that they were all using the codebook similarly.

Following this process, the codebook definitions were refined again before moving forward to code the remaining interview transcripts. New codes that emerged during the coding process were added to the codebook and applied to previously coded interview transcripts. Each interview transcript was coded by one coder, and then checked by a second coder. Any discrepancies that arose during the checking process were discussed and resolved by the initial coder and checker. The three coders met with Katz-Wise biweekly to discuss any issues that arose during the coding process and to further refine the codebook. After all interview transcripts were coded, Fugate, Flanagan, Touloumtzis, and Katz-Wise completed theoretical coding, in which themes were identified from the codes and organized into a conceptual model to describe the data (see Figure 1). Budge reviewed the results of the theoretical coding process.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of transgender and gender nonconforming youths’ identity formation.

Results

Analysis of both caregiver and youth interview transcripts resulted in 29 codes and 40 sub-codes, which are listed in Table 2 with the number of youth vs. caregiver excerpts coded for each code and sub-code. Table 2 also shows the breakdown of excerpts for each code by age group of the youth: age 7–12 years vs. age 13–18 years. To elucidate the complex pathways of transgender identity development, the codes and sub-codes were organized into a conceptual framework with seven overarching themes (see Figure 1): 1) trans identity development, 2) sociocultural influences/societal discourse, 3) biological influences, 4) family adjustment/impact, 5) stigma/cisnormativity, 6) support/resources, and 7) gender affirmation/actualization. Arrows in the model signify ways in which the themes interact. The model depicts sociocultural influences/societal discourse and stigma/cisnormativity as influencing transgender identity development. Bi-directional arrows indicate reciprocal processes. Whereas a family, and the ways they adjust to their child’s gender identity, influences a youth’s transgender identity development, a youth’s change in gender identity also impacts their family. Therefore, developmental pathways among TGN youth occur in transaction with both families and the social environment. Below, we discuss in greater detail each of the seven themes and related codes that illuminate the experiences of transgender identity development from TGN youths’ and caregivers’ perspectives.

Table 2.

Number of Excerpts within Codes and Sub-Codes among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youth and Caregivers from the Trans Youth Family Study

| Theme | Codes and Sub-Codes | Excerpts from Youth Interviews | Excerpts from Caregiver Interviews | Excerpts from families with youth ages 7–12* | Excerpts from families with youth ages 13–18* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Trans Identity Development | Appearance | 16 | 8 | 11 | 13 |

| Clothing and hair | 67 | 167 | 135 | 99 | |

| Pass or go stealth | 11 | 9 | 4 | 16 | |

| Perceived by strangers | 7 | 18 | 14 | 11 | |

| Child dissatisfaction with gendered body | 5 | 22 | 14 | 13 | |

| Resisting classification into binary | 37 | 27 | 24 | 40 | |

| Timing of gender transition | 9 | 19 | 15 | 13 | |

| Developmental timing | 13 | 18 | 20 | 11 | |

| Gradual transition | 7 | 11 | 15 | 3 | |

| Immediate transition | 12 | 23 | 15 | 20 | |

| Timing of trans identity realization | 9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Developmental timing | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| Gradual realization | 10 | 10 | 17 | 21 | |

| Immediate realization | 14 | 24 | 48 | 16 | |

| Using/discussing use of labels/pronouns | 51 | 41 | 29 | 63 | |

|

| |||||

| 2) Sociocultural Influences/Societal Discourse | Activities/toys differing from gender norms | 13 | 68 | 56 | 25 |

| Dominant trans narrative | 3 | 9 | 5 | 7 | |

| Adhering to perceived dominant trans narrative | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Contradicting/not adhering to perceived dominant trans narrative | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Expectations of genital dissatisfaction as “typical” trans experience | 0 | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Understanding gender | 19 | 45 | 48 | 16 | |

| Defining/understanding “trans” | 27 | 20 | 18 | 29 | |

| Societal gender construction | 3 | 12 | 4 | 11 | |

| Words to describe self/child in regards to gender-based behavior | 7 | 33 | 21 | 19 | |

|

| |||||

| 3) Biological Influences | Puberty | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Causing distress | 2 | 6 | 0 | 8 | |

| Trans identity prompted by puberty | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 | |

|

| |||||

| 4) Family Adjustment/Impact | Extended family | 8 | 9 | 10 | 7 |

| Impact on sibling | 7 | 4 | 1 | 10 | |

| Parental perception of youth’s trans identity/gender nonconformity | |||||

| Parental reactions to youth’s trans identity/gender nonconformity | 5 | 110 | 45 | 70 | |

| Acceptance | 5 | 65 | 45 | 26 | |

| Speculation child may be lesbian/gay/bisexual | 0 | 15 | 5 | 10 | |

| Denial | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | |

| Desire for information | 2 | 24 | 10 | 16 | |

| Sense of loss | 0 | 17 | 3 | 14 | |

| Skepticism | 1 | 12 | 5 | 8 | |

| Worry/fear | 0 | 65 | 40 | 25 | |

| Surprise/unexpected | 2 | 17 | 2 | 17 | |

|

| |||||

| 5) Stigma/Cisnormativity | Bullying/dehumanization | 33 | 21 | 26 | 28 |

| Coping with intolerance | 6 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Everyday activities complicated by being trans/gender nonconforming | 3 | 7 | 7 | 3 | |

| Bathroom use | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 | |

| Gendered groups of girls/boys | 5 | 8 | 9 | 5 | |

| Sports | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| Friends/peer relationships (rejection) | 24 | 11 | 19 | 16 | |

| Response of parents’ friends and other adults (rejection) | 4 | 46 | 28 | 22 | |

| School | 23 | 39 | 30 | 32 | |

| Feeling different/not accepted | 20 | 12 | 11 | 21 | |

| Using/discussing use of labels/pronouns | 51 | 41 | 29 | 63 | |

| Being called the wrong name/pronoun | 21 | 9 | 8 | 22 | |

|

| |||||

| 6) Support/Resources | Interaction with trans community/trans people | 30 | 15 | 16 | 29 |

| Friends/peer relationships (acceptance/support) | 24 | 11 | 19 | 16 | |

| Learning about trans | 6 | 5 | 3 | 8 | |

| From books | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| From doctor/medical/therapist | 4 | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| From family, friends/peers | 6 | 8 | 9 | 5 | |

| From technology | 18 | 10 | 5 | 23 | |

| Professional support | 8 | 35 | 15 | 28 | |

| Response of parents’ friends and other adults (acceptance/support) | 4 | 46 | 28 | 22 | |

| School | 23 | 39 | 30 | 32 | |

| Acceptance/support | 26 | 16 | 17 | 25 | |

| Social support | 8 | 2 | 0 | 10 | |

| Camp | 9 | 0 | 3 | 6 | |

| Child perceived parental support | 18 | 0 | 5 | 13 | |

| Overall community support | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | |

| Religious community | 2 | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| Structured support groups | 8 | 13 | 11 | 10 | |

| Ways parents try to support | 3 | 21 | 16 | 8 | |

|

| |||||

| 7) Gender Affirmation/Actualization | Gender affirming surgery | 7 | 6 | 0 | 13 |

| Positive experience with identifying as trans | 6 | 2 | 2 | 6 | |

| Puberty blockers/cross-sex hormones | 6 | 8 | 5 | 9 | |

Notes. Sub-codes are indented beneath codes. Excerpts by age group (7–12 years, 13–18 years) combine youth and caregivers. Excerpts could be coded as more than one code or sub-code. More than one excerpt could be coded as codes and sub-codes for each transcript; number of excerpts could equal number of participant transcripts for some codes, but for other codes, there may be fewer participant transcripts represented in the number of excerpts. Excerpts coded as sub-codes (e.g., clothing and hair) were not also coded as codes (e.g., appearance); therefore, the number of excerpts for codes and sub-codes are mutually exclusive. Response of parents’ friends and other adults, friends/peer relationships, and school appear in both Theme 5 and Theme 6 because these codes cut across both themes. The numbers of excerpts for these codes do not represent the breakdown between rejection and support, except for the sub-codes within school. Similarly, using/discussing use of labels/pronouns appears in both Theme 1and Theme 5 because this code cuts across both themes, particularly regarding the sub-code of being called the wrong name/pronoun.

The most frequent concept to emerge from the interviews was “appearance – hair and clothing.” In response to the interview protocol, both youth and caregivers and families of youth from both age groups frequently mentioned different aspects of how the youth appears. Other concepts, often referring to more abstract or complex ideas, occurred less frequently, but provide equally important insights to understanding transgender identity developmental pathways. For example, although perceptions that puberty prompted transgender identity was only mentioned six times throughout the interviews, it nonetheless suggests that sexual maturation may play a role in catalyzing transgender identification.

In some cases, how frequently a concept came up during interviews varied depending on whether the interviewee was a youth or a caregiver, or whether the family represented a youth age 7–12 years or age 13–18 years. For some concepts, this was unsurprising, based on the questions asked in the interview protocols and the content related to a particular concept. For example, caregivers were more likely than youth to discuss “parental reactions to youth’s transgender identity/gender nonconformity.” Other concepts were mentioned more frequently when coding youth interviews, including “being called the wrong name/pronoun” and “pass or go stealth.” Regarding the youth’s age group, examples of concepts that appeared more frequently among families with youth age 7–12 years were: “appearance – clothing and hair,” engaging in activities or playing with toys that are different from the norms associated with the youth’s sex assigned at birth (“activities/toys differing from gender norms”); and some parental reactions to the youth’s trans identity/gender nonconformity, such as acceptance and worry/fear. Examples of concepts that appeared more frequently among families with youth age 13–18 years were: “pass or go stealth,” resistance of classification into a binary gender identity (“resisting classification into binary”), and other parental reactions to the youth’s trans identity/gender nonconformity, such as speculation that the youth may be lesbian/gay/bisexual, feeling a sense of loss, and feeling surprise.

Theme 1: Trans Identity Development

The development of a transgender or gender nonconforming identity involves a complex interplay of phenomena that constitute processes of being oneself, both internal and external. The conception of transgender identity development, as it was described by youth in this study, included realization of transgender identity, both gradual and immediate, and transition processes. For some families, there were early verbal indicators (saying, “I know I’m not a girl”), behavioral cues (only wanting to play with traditional “girl” toys), and appearance-based preferences (wrapping a towel around their head to mimic long hair) that families interpreted as indications that their child did not identify with their sex assigned at birth. Many youth (and their caregivers) stated that youths’ feelings of dissatisfaction and discomfort with sex-linked physiology, and/or at an older age, bodily changes associated with puberty, prompted a youth’s desire to identify as another gender. For some, primarily youth ages 7–12 years, indication of transgender identification occurred early and was described as “immediate.” One father of an 18-year-old trans boy from the Northeast noted, “It was so immediate that it was just, you know, it wasn’t like he was seven and he said, ‘Oh my god he thinks of himself as a boy.’ It was just kinda always like that with him.” Yet for others, primarily youth ages 13–18 years, the self-realization and transgender identification were less instantaneous. One trans boy from the South, age 14 years, described having an “inkling” when he was five or six, but not being sure, whereas a mother of a trans boy from the Midwest, age 10 years, used the word “gradual” to describe her child’s identity and transition process.

Some youth resisted identifying and being strictly categorized as either a girl or a boy. One youth from the Northeast who identified as a girlish boy, age 8 years, described themself as “I’m a both.” When asked by the interviewer, “Are you a boy, a girl, or neither?”, another gender-fluid boy from the Northeast, age 9 years, responded “Well, half-way between a boy and neither,” later clarifying that he is “like 75% boy and 25% neither.” Although discomfort about identifying exclusively as either a boy or girl sometimes reflected the age of the child and their emergent attempt to navigate their nonconforming identity, other youths’ resistance to female/male gender bifurcation, particularly youth in the older age group, reflected a more deliberate gender identity. One 17-year-old youth participant from the Northeast self-identified as “gender nonconforming,” defined as “people aren’t really fitting into the binary system.” When asked by the interviewer, “Is the identity trans or male permanent or do you think it could change?”, an 18-year-old trans boy from the Northeast answered, “Well, I don’t know, I mean I think that the idea of having like one identity your whole life is a little bit weird.” More than simply being uncertain or confused about their gender identity, youth expressed intentionality and thoughtful certainty when resisting binary gender classification.

The internal process of transgender identity development was often reflected in outward appearance. Appearance preferences often indicated to caregivers that their child may be nonconforming, since clothing and hair are strongly gendered cultural signals. One mother of a trans boy from the Midwest, age 10, described her son as, “Boy. Total boy. And you know, it wasn’t really, like, since age 2 on, like some people say. But, you know, it was probably like more 5ish when he wanted to start wearing his brother’s hand-me-downs.” Still, many descriptions of appearance reflected the individualized diversity of fashion preferences (i.e. for one youth, “punk”) that exist for any individual, whether they are cisgender or transgender. Some youth described their appearance as “gender neutral,” but many described their appearance as aligning with the more “typical” dress of their affirmed gender. Adhering to an appearance that is more “typically” boy or girl reflected authentic preferences, but also served to reaffirm identity and ability to “pass” or “go stealth” as the affirmed gender, a concept that was discussed more frequently among families with youth ages 13–18 years. One trans girl from the Northeast, age 15 years, explained, “I think the best reaction I ever got was from my friend…I told her I was trans and she said ‘so you’re gonna start dressing like a boy now?’ And I was like, ‘no, nope other way.’ And she was like ‘whoa, I wouldn’t have [known you were trans],’ and that was really nice to hear.”

A common theme across interviews was the importance of using the correct identity labels and pronouns. Many caregivers recalled that a key milestone of the transition process was changing pronouns and their child’s name. When a father of a trans girl from the Northeast, age 13 years, was asked about his child’s gender identity, he responded, “Definitely female, there’s no question. I mean she came up with the name, she was adamant about being addressed as a female at school, you know, all things were from her.” For youth, particularly those in the older age group, using the correct pronoun and name was an important step in transitioning to their affirmed gender identity and sense of self, but in many cases, it also was an important indication of respect and acceptance from others. As one trans girl from the Northeast, age 15 years, explained, “I think I care a lot [about pronouns], I think it sort of comes across as an insult when people say ‘he’ or ‘it’ to me because I’m very [feminine] now, I am a female and there’s no question about that…” For another trans girl (identified as such during the interview) from the Northeast, age 14 years, choosing a particular pronoun felt like a misalignment with their identity, but also felt necessary to gain societal acceptance:

“If there were five genders, I wouldn’t be female—I’d be somewhere in the middle. But I’m definitely more on the side of, in terms of if there’s a line down the middle of the spectrum, I’m definitely more on the female side, and so I choose female pronouns.”

When asked about the possibility of using a gender-neutral pronoun, she explained,

“My being trans—and I’m stealth—it would be a lot of things I can’t talk to my friends about, so that is also a roadblock in terms of creating relationships. But, the other thing is that if I used a different pronoun—not male or female—I couldn’t be stealth.”

The themes related to the development of transgender identity were associated with internal processes, reflected in outward forms, and validated by gendered social and cultural norms of legitimacy.

Theme 2: Sociocultural Influences/Societal Discourse

As described in the conceptual model, sociocultural norms and discourse about gender and transgender identity influenced youths’ gender identity development and the ways in which caregivers responded and adjusted. Beliefs about gender more broadly shaped the way caregivers perceived and responded to their child. Caregivers defined gender expression as both an internal process that molds identity and preferences, as well as outward expression that reflects (or rejects) societal expectations of how women and men look and act in the world. One father of a girlish boy from the Northeast, age 8 years, explained, “I sort of view [gender expression] as a combination of visible signs of what somebody has for preference, in terms of likes and dislikes, that can be clothing, appearance, activities, mannerism, speech, all that kind of stuff.” Other caregivers articulated that much of gender expression is based off of “gender stereotypes” and determined by social circumstances. One mother of a trans boy from the South, age 14 years, explained, “I mean gender expression in children, I think so much of it is society… I’m not sure if there’s any real, honest to god, innate gender expression.” Caregivers articulated that gender expression is only a reflection of, but not exclusively grounded in, sex-linked biology. As one mother of a trans boy from the Northeast, age 18 years, explained, “Gender expression, I would say it’s not looking at the physical body but how somebody expresses themselves as a person.”

A common heuristic to make sense of children being assigned a female sex at birth, but identifying as a boy, is use of the term tomboy. One mother of a trans boy from the Midwest, age 9 years, recalled, “And even at first, like trying to talk with the teachers, or whoever, they’re like ‘Yeah, she’s a tomboy.’ Some youth also mentioned the moniker; a trans boy from the Northeast, age 17 years, stated, “I guess people probably thought of me as a like a tomboy…” The label of tomboy provides a precedent for societal tolerance and an explanatory tool for understanding girls acting and dressing in ways traditionally associated with boys.; a cultural equivalent does not exist for boys. Thus, a child’s transgender identity comes as a surprise, or is met with skepticism by both caregivers and other adults. One grandmother of a trans boy from the Midwest, age 10 years, who was the youth’s primary caregiver, described the way she thought of her grandchild’s identity before his transition: “At that time, in my mindset, it was still tomboy,” while a mother of a trans boy from the Northeast, age 10 years, described the tomboy assumption as undermining her recognition of her child’s transgender identity. She explained,

“She [her child] would say that she wanted to be a boy and we asked her more so that we would know what to do, not trying to press it out of her, but just to kind of say, you know, ‘What do you want?’ I think one of the hardest parts, too, is you, at this age, you know you ask that and people always say, ‘Oh…just wants to be a tomboy.’ This kid really identifies as a boy as far as we can tell and we wanted, we ask her just so that we can do the right thing for her.”

In addition to societal expectations specific to girls and the idea of a “tomboy,” caregivers’ experiences with their child’s transgender identity were also shaped by expectations for what the transgender experience should be. A common feature of an imagined transgender narrative is that “the families knew from birth.” A father of a trans boy from the Northeast, age 18 years, explained, “Some kids at age 3 are like, I’m a boy, you know, and they just, do things, like pee standing up, and complain to their parents that they don’t have a penis, and we never had anything like that.” Later on, when explaining why his child’s transgender identity came as a surprise, he reiterated, “He never said the classic what-the-book-says. Like, kids say, ‘I feel like I am a boy inside.’ You know, that’s the classic.” Put more bluntly, a mother of a trans girl from the Northeast, age 14 years, explained, “There’s this story and there’s this political story that everybody needs to have right now about what transgender is and 4 year olds wanting to cut off their penises…”

Youth often explained gender expectations through concrete examples that reflected common gender stereotypes related to appearance and activities/toys. One 15-year-old trans girl from the Northeast responded, “Boys they probably think of sports, more physical activities and probably like jeans and sweatshirts, girls they probably think of more safe activities, like cooking or something, and they probably think of like pink and skirts.” Youth also challenged such strict delineations of girl/boy associations. For example, one trans boy from the Northeast, age 9 years, explained, “I think that if they wanna like have painted nails and they’re a boy, still they could do that and I don’t say they’re a girl or anything.” A youth from the Northeast who described himself as a girlish boy, age 8 years, indicated that he struggled to fit into either gender category. He explained, “I don’t fit in with boys, I fit in with girls, but really I’m not with both because... I don’t really fit in with either.” His father added, “It’s not that he’s uncomfortable with who he is, he’s just I think he’s more comfortable with the way he expresses himself.” A 17-year-old trans boy from the Northeast also expressed frustration with gender expectations, stating “Gender segregation in society and how angry it makes me, I think it’s really not cool that people’s gender ends up being a part of every conversation” Gendered standards of what is socially legitimate are inherent to any child’s lived experiences. Yet for transgender or gender nonconforming youth, the sociocultural reality presents a unique challenge to their identity formulation process.

Theme 3: Biological Influences

In addition to sociocultural influences, biological processes also influenced transgender identity formation. Among families with youth ages 13–18 years, puberty was cited as a developmental stage that both catalyzed transgender identity realization, but also complicated youths’ sense of self as their bodies changed in ways that were not only discomforting, but at odds with their affirmed gender identities. One mother of a trans girl from the Northeast, age 14 years, recalled her daughter’s experience with puberty, sharing that, “She was really very, very uncomfortable about every possible piece of male puberty, just like dreading every single thing that she knew was gonna happen to her body and her voice and whatever.” Another mother of a trans boy from the Northeast, age 17 years, believed that her child’s binary gender identity became starker once puberty started: “Until puberty hit, that was kind of, he was kind of comfortable being in that, a little bit of that middle place.” In considering how transgender identity develops over time, it is important to recognize that in addition to social and cultural influences, biological developmental processes also play an important role.

Theme 4: Family Adjustment/Impact

The ways in which a family adjusts to, and is impacted by, a youth’s transgender identity may affect the youth’s identity development and access to support/resources related to their gender identity. For instance, more supportive caregivers may be more likely to connect their TGN child to gender-affirming medical and support resources. The majority of the caregivers in this study indicated that they were currently supportive of their child’s transgender identity. One trans boy from the Northeast, age 17 years, described his mother’s initial reaction as, “At first she was like ‘Well I don’t really understand this, but I’ll work on understanding this and then I will support you’ and that was really great.” Other caregivers were also quick to accept their child’s transgender identity; one father of a trans girl from the Northeast, age 13 years, said, “As soon as she first mentioned it [being transgender] and we were supportive of that, it just flew from there.” Yet some caregivers never anticipated their child may identify as transgender: “…never dawned on me at all! I was absolutely, it never dawned on me! When the kid sat down at the kitchen table and told my husband and myself, I was totally floored” (mother of a trans boy from the South, age 14 years). Another trans girl from the Northeast, age 13 years, described her mom’s reaction as, “She like got her shock face, like her face was in shock.”

Whereas the initial surprise gave way to acceptance for some caregivers, others described a lingering skepticism and the existential question of, “How do we know that you’re really trans?” Some caregivers, more often those of youth ages 13–18 years, wondered if perhaps their child was going through a phase and others questioned whether their child was gay. One father of a trans girl from the Northeast, age 15 years, confessed feeling a sense of denial, saying, “I mean it was hard, it wasn’t automatic but I always hoped that it would go away, I really did, I just hope he’s gay and he’ll grow out of this part of it.” Caregivers sometimes described “a sense of loss” of their child’s former gender. A father of a trans boy from the Northeast, age 17 years, explained, “… because the little girl I knew and grew up with is disappearing and is turning into something else that I don’t know yet and you start to mourn that.” Caregivers, particularly those of youth ages 7–12 years, also expressed fear for their child, immediately as well as in the future. Fears included bullying and how other kids would treat their child, physical harm, risks associated with “medical stuff,” ability to find a significant other, and more generally, “acceptance, ease in life, just everything.” Although extended family members were sometimes mentioned as being less supportive, a youth’s caregiver(s) seemed to exert the greatest influence over transgender identity formation. The range of reactions, emotions, and opinions caregivers expressed shaped the ways in which they provided support for their child, and in turn, how their child navigated the complex process of being gender nonconforming in a gender delineated society.

Theme 5: Stigma/Cisnormativity

Experiences of discrimination and hostility contributed to the ways in which transgender youth grappled with gender identity and expression across different contexts. The degree to which youth experienced intolerance was varied. Whereas certain institutions (e.g. schools, camps) or people (e.g. classmates) could be a source of support for participants (see “Support/Resources”), for others, they were sources of struggle and stigma. For some youth, school was described as a site of marginalization and torment. One father of a trans boy from the Midwest, age 9 years, described how his child was prohibited from rooming with other boys at a school-sponsored camp; he instead would have to stay alone, in his own room. A trans boy from the South, age 14 years, reported receiving a suspension for going in the “wrong” bathroom at school.

Youth often reported being the victims of bullying from classmates, both physical and verbal. Although some youth recalled being intentionally called the wrong pronoun, or referred to as “it,” negative experiences in school may not have always been overtly due to being transgender, but rather being different: “I was never like bullied, but I was like actively excluded. So, they could be mean to me without feeling bad about it, because they weren’t actually doing anything, they just weren’t letting me in” (trans boy from the Northeast, age 17 years). Although almost every youth could recall an instance in which they were made to feel bad about their identity, some reported only isolated negative experiences, whereas other youth recalled systematic harassment by classmates, which was related to their identity developmental processes.

Everyday activities were also complicated by being trans, creating situations ripe for stigmatization. Typical child/adolescent experiences, mentioned in families of youth from both age groups, which were complicated by gender nonconformity included playing sports, using single-gender bathrooms, formal or informal divisions between girl and boy (friend) groups, and camp. A girlish boy from the Northeast, age 8 years, explained the challenges of using gendered bathrooms: “So I’m washing my hands in the bathroom, and somebody walks in and says ‘Are you a girl or a boy?’ And I just get so annoyed, I just, I’m just, I just, it really annoys me.” Another common situation involved single-gender activities. A father of a trans girl from the Northeast, age 7 years, discussed an instance in which, “The girl had a birthday and only invited ‘girls,’ it was a girly party and [youth] wasn’t invited because she wasn’t a girl at the time and she got very upset about that.” Several participants discussed quitting sports or not joining at all, because they could not play on the team that matched their gender identity, or because they felt uncomfortable wearing form-fitting uniforms (e.g., swimming, crew). These social and institutional cisnormative (cultural views of cisgender as the default) barriers, and overt instances of stigmatization and bullying of transgender youth, influenced the way in which the youth perceived themselves and their gender identity.

Theme 6: Support/Resources

Similar to the ways in which stigma and intolerance were formative for youths’ transgender identity, receiving social support and being able to access resources also shaped the ways in which youth came to understand their gender identity. Social support for participants took many forms, including professional support, support groups and interactions with other transgender youth and their families, and broader community support. Some schools provided important supports that affirmed youths’ gender identity and transition. An 18-year-old trans boy from the Northeast talked about having a “really good group of friends who were okay with it [his transition],” and having supportive teachers:

“I recently had chest surgery so I was out of school for like a month and when I came back all the teachers were like ‘Congratulations,’ they were really accepting of it. The teachers that do accept it, I know they accept it, but I don’t know about the other ones.”

Friends were sometimes mentioned as a source of support for participants, as were more formal institutions, including church groups (specifically, Unitarian Universalist churches) and a camp for transgender children. One mother of a trans boy from the Northeast, age 9 years, recalled the reaction of her son’s best friend when he told him he was transgender:

“[Youth] told him the next day at school on the swings so when her [friend’s mother’s] son came home she said well do you know what transgender means? And her son says ‘Yeah, he’s my best buddy, I don’t care that he doesn’t have a penis.’”

Both youth and caregivers talked about the importance of being in spaces where they could talk about their experiences. A mother of a trans boy from the South, age 14 years, recalled,

“We went to [support group], you know, we dropped him off and picked him off like two hours later and the kid said, ‘This is the first time I have ever walked into a room full of kids and felt like I belong.’”

Structured programs (e.g., support groups, mentoring organization) were often cited as connecting youth with other transgender youth, providing opportunities to both mentor and be mentored. Caregivers also relied on formal groups, including a mother of a trans boy from the Northeast, age 9 years, who shared, “I’m in a caregiver support group which is great to know that I’m not alone. I’m in a couple, I’m in one that I physically attend and then I’m in a few online. One 15-year-old trans girl from the Northeast suggested that because her family and friends already knew who she was, identifying as transgender was met with indifference:

“I think what stands out is the lack of reaction, I don’t think they really cared, ‘cause they always knew I like dolls, so they were just like, ok. It’s not really that different from before, so there wasn’t anything that they really needed to change.”

Theme 7: Gender Affirmation/Actualization

A tangible way in which caregivers supported their child was in facilitating processes of gender actualization, by which TGN youth were fully affirmed in their gender identity. In addition to seeking social support groups and transgender advocacy organizations, caregivers, particularly of youth ages 13–18 years, also supported their child by seeking counseling and medical advice. In some instances, it was decided that physiological interventions, including gender affirming surgery, puberty blockers, and/or cross-sex hormones were appropriate. Although only a few youth discussed surgery during their interview, puberty blockers and hormones were discussed as a more viable option, especially for younger youth. One mother of a trans boy from the Northeast, age 9 years, described the family’s decision to proceed cautiously: “We’ll put him on the blockers and give him a chance to grow into himself and then see where he is at 14, 15, maybe then starting cross-hormone therapy if it’s appropriate for the way he feels.” A mother of a trans boy from the Midwest, age 10 years, expressed some concerns about safety and long-term consequences of treatment, saying “Just reading about the hormone blockers, the controversy of it, and you know, do they really know for sure there’s no long-term effects? Like, you know, there’s been debate and stuff about that.” Although facilitating the physical aspects of gender actualization is only one of many ways in which a caregiver can support their child, it was an important aspect of the youth’s transgender identity development for a subsection of families.

Discussion

Many of the key findings in this study align with prior research related to transgender identity development (Olson et al., 2015; Bockting, 2014; Devor, 2004). Although this study did not seek to organize findings as a series of developmental milestones, many of the characteristics of different stage theories of transgender development are supported by the themes of developmental pathways that emerged from this study, as well as previous studies’ more general emphasis on transgender identity development as encompassing both inter- and intrapersonal influences (Devor, 2004; Hiestand & Levitt, 2005). Still, the unique characteristics of childhood–being less conscious of violating gender norms, having parents to support and provide resources, and for younger participants, not having to concurrently navigate sexual orientation development–render some of these previous models less relevant for TGN youth. Research that incorporates a life course perspective has identified certain themes that were also present in participants’ narratives in the current study, including an early sense of body-mind dissonance, managing and negotiating identities, and transition (Morgan & Stevens 2012). Findings from the current study highlight the need to understand transgender identity development as a complex and fluctuating process, rather than one that is linear. In addition, this study illustrates the concept of developmental pathways of forming a transgender identity that are transactional, in that both youth and caregivers are involved in this process, and each family member’s experience affects the other family member. Developmental pathways may also be different for families with younger vs. older youth.

Findings from other research on transgender identity development are often based on a retrospective lifespan approach in which experiences and perspectives are filtered through an adult lens–either trans adults or caregivers of trans youth (Rahilly, 2015; Kuvalanka et al., 2014; Morgan & Stevens, 2012). In the current study, within each theme, there were a number of differences regarding codes and sub-codes which emerged from caregivers’ narratives vs. TGN youths’ narratives vs. both. For example, within the theme of trans identity development, caregivers were more likely to discuss their child’s dissatisfaction with their gendered body, TGN youth were more likely to discuss appearance and both caregivers and TGN youth discussed the timing of the youth’s gender transition. Without including both caregivers and TGN youth, we would have missed several important themes related to transgender identity development. By including the perspectives of TGN youth across two age groups, we could understand a different viewpoint of transgender identity development than has been assessed previously–that of TGN youth themselves–and incorporate their perspectives and experiences into our understanding of this developmental process.

Realization of a transgender or gender nonconforming identity often assumes transitioning from one binary gender category to the other. Yet in this study, several of the youth from both age groups resisted categorization as either a girl or a boy. Youth who felt that the gender binary did not fully capture their identity included older participants who possessed a sophisticated, gender studies-informed language for expressing their identity, as well as younger participants, who described themselves as “I’m a both” (age 8 years) or I am “like 75% boy and 25% neither” (age 9 years). Recognition that some TGN youth seek to identify outside the traditional gender binary is an important finding from this study, and prompts the need for greater understanding of how best to support youth who do not wish to identify strictly as a boy or girl, or who express fluidity between genders. A qualitative study of resiliency among transgender youth found that one of the key themes of resiliency was the “ability to self-define and theorize one’s gender,” which referred to use of a youth’s own words and concepts to describe and define their gender (Singh et al., 2014). Singh et al.’s research suggests the importance of allowing TGN youth to develop their own language to describe their gender, including the use of terms to describe a non-binary gender identity.

Another key finding is the developmental pathways associated with the realization of a TGN identity and the process of undergoing gender affirmation to affirm their authentic gender. For some youth, particularly those in the younger age group, the recognition that their sex-linked biology did not match their gender identity was immediate and known from a young age. Yet for others, particularly those in the older age group, the process was either more gradual, or not realized until they were older. Although most professionals agree there is a biological aspect to transgender identity, people navigate their lives in social environments in ways that also give meaning to their existence. For TGN youth, forming a transgender identity occurs within both the family and larger social context, with developmental pathways that are transactional between youth and caregivers. Still, just as some of the participants in Devor (2004) discussed puberty as a catalyst for realizing their transgender identity, we also found that puberty played an important role for several youth. Whereas past transgender identity research has proposed that there are different stages of development (e.g., Bockting & Coleman, 2007; Morgan & Stevens, 2012), findings from the current study suggest that for youth, there is no standard timeline or pace of progression. Although some youth shared similar experiences, processes of becoming transgender were not always marked by tell-tale signs, such as rejecting biological genitalia at a young age. Rather, findings from this study suggest that although there are commonalities, efforts should be taken to avoid reifying youths’ transgender identity development as a singular experience.

More than focusing on the experiences of TGN youth, the current study aimed to place their gender identity development in relation to their caregivers as a key component of the overall family system, consistent with a Family Systems Theory approach (Cox & Paley, 1997; Minuchin, 1985). Families are impacted by the challenges associated with supporting, and in many instances advocating for a transgender child, yet our research also demonstrated that transgender identity development among youth is deeply influenced by the response and actions of a caregiver (e.g. Ryan et al., 2010). Furthermore, the caregiver’s experience is influenced by the developmental processes undergone by the youth. Although the majority of caregivers in our study were supportive of their child’s transgender identity at the time of participation, caregivers described a range of initial emotional responses. Even though many caregivers struggled to cope with and make sense of their reactions to their child’s identity, they were also compelled to find ways to support their child (e.g., join support groups, seek professional assistance), as well as protect their child from stigma, discrimination, and hostility (Katz-Wise et al., 2017).

A particular challenge for caregivers trying to navigate their child’s gender identity related to Rahilly’s (2015) concept of “gender hedging” and “playing along.” Caregivers in the current study frequently recalled making decisions for their child that either set boundaries regarding gender-atypical behaviors and appearances, or embraced their child’s preferences for how they presented themselves. Caregivers’ efforts to make their children adhere to societal norms of gender presentation were rarely grounded in an intention to suppress gender identity, but rather were motivated by a constant struggle to ensure their child was protected from judgment, hostile questioning, bullying, and harm, while also affirming their gender identity by honoring their desired appearance.

For youth growing up in a historic period of greater awareness and visibility of transgender people, and in some contexts, greater acceptance, transgender identity development differs in many ways from the experiences of older TGN individuals who first identified as transgender decades ago. Almost all TGN youth in the current study could recall an instance of being bullied because they are TGN, with some youth sharing more painful and trauma-inducing experiences than others. This is consistent with previous research indicating that gender nonconforming and non-binary youth experience violence related to their gender identity and expression (Wyss, 2004). Yet it is also important to note that many of the youth reported feeling “lucky” to have supportive friends and families and described relatively prosaic “coming out” experiences. TGN youth and their caregivers often emphasized the importance of having different support systems, including transgender-specific spaces, such as youth and/or parent support groups, or summer camps for transgender children, as well as other community spaces, such as churches and schools. An important implication of our research is that, although caregivers play a crucial role in ensuring a healthy and positive gender identity for their child, access to additional sources of support can further insulate a child from marginalization and trauma, and also provide much-needed support for caregivers themselves. Considering that most families in the current study were White race/ethnicity, it will be important in future research to determine whether families of color need different types of support, particularly if they do not feel welcome in primarily White spaces, such as many support groups.

Recently, there has also been a proliferation of policies, both protective and restrictive, regarding transgender bathroom use in public places and in schools. Findings from the current study found that schools were institutions that could affirm and support students, but also begat marginalization and torment. Policies regarding bathroom use and sleeping arrangements on overnight trips that often isolated TGN students from their same-(affirmed)gender peers were brought up as painful experiences that were detrimental to healthy gender identity formation among youth from both age groups. This draws attention to the important role schools must play in affirming the gender identity of transgender children and dismantling harmful policies. Research has begun to examine the effects of structural stigma on the health of transgender adults (e.g., Perez-Brumer et al., 2015), but no research has assessed these links among TGN youth. In addition to recognizing how TGN youth are nested within family systems, attention should be given to the importance of schools to TGN youths’ development and gender identity processes. This would be a fruitful topic for future research.

Limitations

The challenges associated with recruiting TGN youth, due to low prevalence in the general population, as well as the relative invisibility of this marginalized group, resulted in limitations to our research. Although participant recruitment included three geographical locations (Midwest, Northeast, South), the study sample was limited to predominantly White, mid- to high-income families in these two regions. This likely limits generalizability to families of color and those who are low-income. Future research should investigate the experiences of these families. Furthermore, most families were recruited from the Northeast, due to difficulties recruiting families from the Midwest and South, where (anecdotally) families were more reluctant to participate for fear of being “outed” in their communities. Participants were recruited through transgender support organizations for families with transgender youth. For caregivers to learn about the study and be willing to participate, it is likely that they had already accepted their child’s identity to some degree and were seeking resources and assistance. This research may overly represent families that support their TGN children, compared to the general population, because it is unlikely that a parent who rejects or denies that their child is transgender would have agreed to participate in this study. Although this study examined the experiences of TGN youth and their families, only TGN youth and caregivers were interviewed. To fully understand the bidirectional relationship between a TGN youth and their family, it would be helpful to expand the definition of family beyond caregiver, to include siblings other co-residing family members, such as grandparents. Finally, although we were able to include a number of youth with non-binary identities, the majority of the sample of TGN youth identified as either a trans girl or trans boy. Future research could center the experiences of non-binary youth to better understand their unique developmental processes.

Conclusions

This research makes a valuable contribution to the relatively small body of research on transgender identity development among TGN youth, through informing the ways in which individuals, families, communities, and institutions support transgender youth and ensure that they grow up to be healthy adults who are affirmed in their gender identity. We hope that by providing insight into the varying experiences of families with a TGN child related to the formation of a transgender identity, this research will inform everyday interactions, and broaden understanding and representation beyond stereotypical tropes and singular narratives that perpetuate interpersonal discrimination and intolerant school policies and state laws.

Another aim of this study is to contribute to ongoing conversations about assumptions related to “legitimate” gender roles. Just as having a TGN child expanded caregivers’ understanding of gender, we hope to challenge readers to consider ways in which societal expectations of a gender binary narrowly define norms that may render transgender youth vulnerable to discrimination and trauma. Given the sophistication with which youth discussed gender in our study, it is developmentally appropriate and necessary to involve youth in conversations to alleviate stigma related to transgenderism. Such conversations can shift us toward a sociocultural reality that facilitates, rather than impedes, the identity formation process of transgender youth.

In sum, we suggest that, although transgender identity development among youth is inextricably linked to individual biological processes, it is also influenced by how caregivers adjust and respond to their child, and how a youth is supported and able to access resources, or conversely, experiences stigma and oppression in a cisnormative society. Furthermore, developmental pathways of transgender identity development among TGN youth are transactional between youth and caregivers, and may differ among TGN youth of different age groups. The ways in which these moving parts fit together results in a transgender identity process that is as plural as the circumstances in which such identities come about. Yet the commonalities experienced by many of the study participants–the importance of using correct gender identity labels/pronouns, the trauma associated with discriminatory bathroom and/or school policies, and the understanding that not all children “come out” or express their gender identity in the same way–provides insight regarding how best to support not only transgender youth, but also the familial networks tasked with ensuring they nurture happy, healthy, TGN youth who are affirmed and supported in their identity.

Acknowledgments