Abstract

Neoplastic meningitis (NM) is a devastating complication of solid tumors with poor outcome. Some randomized clinical trials have been conducted with heterogeneous inclusion criteria, diagnostic parameters, response evaluation and primary endpoints. Recently, the Leptomeningeal Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (LANO) Group and the European Society for Medical Oncology/European Association for Neuro-Oncology have proposed some recommendations in order to provide diagnostic criteria and response evaluation scores for NM. The aim of these guidelines is to integrate the neurological examination with magnetic resonance imaging and cerebrospinal fluid findings as well as to provide a framework for use in clinical trials. However, this composite assessment needs further validation. Since intrathecal therapy represents a treatment with limited efficacy in NM, many studies have been conducted on systemic therapies, including target therapies, with some encouraging results in terms of disease control. In this review, we have analyzed the clinical aspects and the most recent diagnostic tools and therapeutic options in NM.

Keywords: Neoplastic meningitis, diagnostic criteria, liquid biopsy, targeted therapies

Introduction

The term neoplastic meningitis (NM), also known as ‘leptomeningeal metastasis’, refers to the spread of tumor cells to leptomeninges (pia and arachnoid) and subarachnoid space, and their dissemination through the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). An increased incidence of NM has occurred because of the development of effective antineoplastic treatments for solid tumors and improvement of diagnosis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).1 The majority of the antineoplastic drugs are able to control the systemic disease, but do not penetrate an intact blood–brain barrier (BBB) in adequate concentrations, thus the central nervous system (CNS) is a frequent site of relapse. NM is the third most common CNS complication of cancer following brain metastases and epidural spinal cord compression, and represents a challenge for clinicians in terms of diagnosis and treatment.

For a long time, diagnostic tools for NM were not standardized and there were no generally accepted criteria to define patient subgroups that might benefit from therapy. Recently, the Leptomeningeal Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (LANO) Group and the European Association for Neuro-Oncology/European Society for Medical Oncology (EANO/ESMO) have proposed clinical and radiological recommendations2,3 in order to provide diagnostic and response criteria for NM, both for enrollment in clinical trials and in clinical practice.

Treatment of NM aims to improve neurological symptoms and extend overall survival (OS), especially when the disease is diagnosed early on. Currently, there is not a standard treatment and several approaches, such as radiotherapy (RT), intrathecal or systemic therapies, can be employed. Despite these aggressive therapeutic options, the median overall survival (OS) is poor and ranges between 6 and 8 weeks without tumor-specific treatments, while it may be prolonged to 3–6 months with NM-directed therapies, including target therapies and immunotherapy as well.4

In this review, we analyzed the clinical aspects and the most recent diagnostic tools and therapeutic options in NM.

Epidemiology

NM is a frequent complication in patients with solid tumors (4–15%) as well as in patients with lymphoma or leukemia.5,6 The most common primary tumors metastasizing to the leptomeninges are breast and lung carcinomas, melanoma, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and acute lymphocytic leukemia. Because of the improved efficacy of antineoplastic treatments, there is an increased number of NM from solid tumors that were rarely associated with NM in the past, such as prostate, ovarian, gastric, cervical, and endometrial cancers.7 Furthermore, NM is diagnosed in 1–2% of patients with primary brain tumors, such as ependymomas, medulloblastomas, germinomas and gliomas.8 In more than 70% of patients NM develops in the setting of an active systemic disease, while in 20% of patients it occurs in association with a stable disease, and in up to 10% of patients it is the first manifestation of cancer.

Some risk factors for developing NM have been recognized: concomitant brain metastases are associated with NM in 33–54% of patients with breast cancer, 56–82% with lung cancers and 87–96% with melanomas.9–11 Within breast cancers, the lobular subtype, triple-negative or human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) subtypes display a specific tropism for CNS,12,13 as well as the expression of the mutant epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)14 or the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).15,16 To date, both mutations are targeted by EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and ALK inhibitors, respectively, with encouraging data regarding disease control. Conversely, the role of risk factors (i.e. BRAF mutation) in patients with melanoma and NM has been investigated in a few large cohorts without any relevant evidence.

Surgery may be a factor influencing the leptomeningeal dissemination: in particular, the opening of the ventricular system during resection of a brain metastasis (BM) or primary brain tumor can be associated with CSF spreading, especially in posterior fossa lesions and when using a piecemeal compared with en-block resection.17,18 Moreover, the incidence of NM seems higher in patients treated with surgery followed by stereotactic radiosurgery compared with radiosurgery alone.19

Pathogenesis

Tumor cells may reach the subarachnoid space by means of a hematogenous spread through the venous or arterial circulation, a growth along nerve and vascular sheaths, a migration from a tumor adjacent to CSF, or by a iatrogenic spread following resection of a BM.20,21 Tumor cells may disseminate through the CSF along the entire CNS with a predilection to invade regions with slow CSF flow or gravity-dependent sites, such as basal and lumbar cisterns or posterior fossa. Recent data suggest that the increased activity of some matrix metalloproteases, including matrix metalloproteasis 9 (MMP-9) and the A disintegrin and metalloproteasis 8 and 17 (ADAM8 and ADAM17), may play a role in malignant invasion in the CSF.22

Diagnosis

Clinical manifestations of NM are typically multifocal and may involve one or more segments of the neuroaxis: cerebrum (15%), cranial nerves (35%), or spinal cord (50%).7 Clinicians need to be careful in the evaluation of a patient with suspected NM because any site in the CNS could be potentially involved, and signs and symptoms may overlap with those of parenchymal brain metastases or mimic treatment-related toxicities and, rarely, neurological paraneoplastic syndromes.

The most common clinical presentations are as follow:

headache (66%) related to an increased intracranial pressure, blockage of the CSF flow and obstructive hydrocephalus;

spinal symptoms and signs, including lower motor neuron weakness (46%), sensory loss, radicular and back/neck pain, bladder, sexual and bowel dysfunctions9,23,24;

diplopia (36%), visual impairment, hearing loss, facial weakness due to cranial nerve palsies (cranial nerves II, III, IV, VI, VII, VIII);

dysphagia as a later symptom, often correlated with impaired consciousness;

mental changes and seizures, especially in the case of coexistent encephalopathy;

gait disturbances due to cerebellar or sensitive ataxia;

nausea/vomiting.

Overall, diagnosis is based on three tools: a standardized neurological examination; CSF cytology in solid cancers and flow cytometry (FC) in hematologic malignancies; brain and spinal cord contrast MRI, while radioisotope CSF flow study is useful in patients to be treated with intrathecal therapy only.

Rarely, leptomeningeal biopsy is performed when CSF cytology is repeatedly negative and MRI unrevealing.

Neurological examination

A careful neurological examination is mandatory to reveal multiple deficits and a standardized evaluation should be used at diagnosis and during follow up.2 The Neurologic Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (NANO) scale, that is currently employed to evaluate the neurological status in patients with brain tumor, is not useful enough in NM due to the low sensitivity to detect the multilevel involvement of the CNS typically seen in NM. In this regard, the LANO Group has created a standardized assessment of the neurological examination with multiple domains that reflect the sites of NM involvement. Several domains are investigated, such as gait, strength, sensation, vision, eye movement, facial strength, hearing, swallowing, level of consciousness and behaviour. The level of fuction in each domain is graded as 0 (normal), 1 (slight abnormal), 2 (moderate abnormal) and 3 (severe abnormal). Based on this neurological assessment, progressive disease in NM is characterized by a change from level 0 to level 3 (or level 2 in domains with three levels only) in any domain. This instrument was designed to be as simple as possible in order to be utilized not only by neurologists, but also by oncologists, nurses, and physician assistants, but needs to be prospectively validated.

Other important aspects are the neurocognitive functions and the self-perception of quality of life: in this regard, the patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and performance status could be prognostic indicators of both progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in patients with primary and metastatic brain tumor.25 Some experts have proposed adding the MD Anderson Cancer Center Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module (MDASI-BT) and Spine Tumor Module (MDASI-ST) to better define symptoms, such as pain or incontinence, which otherwise would not be easily detected.2 Although there is a lack of validated data in the literature, it would not be surprising if both quality-of-life measures and neurological examination provide additional insights regarding treatment response and tolerability of treatments.

Neuroimaging assessment

Brain and spinal cord MRI without and with contrast enhancement, using at least 1.5 Tesla field strength, is highly recommended for the neuroradiological assessment in suspected NM.26 Contrast-enhanced T1-weight and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences are the most sensitive to show NM lesions.27 Contrast brain and spinal cord MRI must be performed at baseline and following treatments.

The neuroradiological diagnosis in NM is challenging and MRI in some patients may be negative. Sensitivity and specificity of brain and spinal cord MRI have not been fully investigated so far, due to the limited number of publications, but it has been estimated in the range of 66–98% and 77–97.5%, respectively.28,29 Pauls and coworkers reported a higher sensitivity of contrast-enhanced T1 imaging in detecting NM from solid tumors compared with hematological malignancies.30 Moreover, the MRI sensitivity is superior in NM from solid tumors with elevated CSF cell counts in comparison to those with normal CSF counts.31

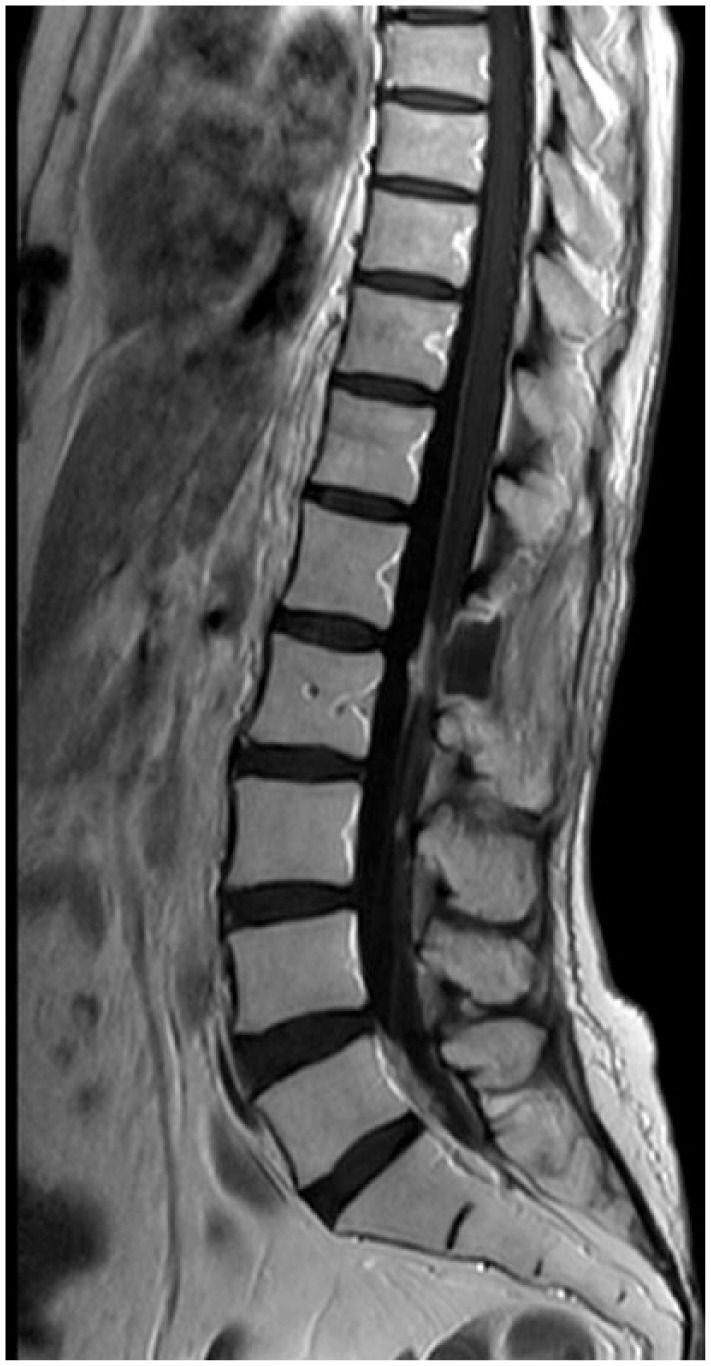

Linear or nodular enhancing lesions of the cranial nerves and spinal nerve roots (e.g. cauda equine), brain sulci and cerebellar foliae are the most common findings32,33 (Figures 1–3). NM lesions typically are small in size (<5 mm) and with complex geometry, thus a quantitative analysis with current MRI technology is difficult.34 Other neuroimaging techniques (MRI spectroscopy, MRI perfusion, MRI diffusion and positron emission tomography) are not currently employed. Communicating hydrocephalus could be observed in 11–17% of patients, and CSF flow studies, including radioisotope cisternography, are useful in the case of suspected CSF blockage or altered intrathecal drug delivery.35,36

Figure 1.

Enhanced lesions in the cauda equine.

Figure 2.

Enhanced lesions in brain sulci.

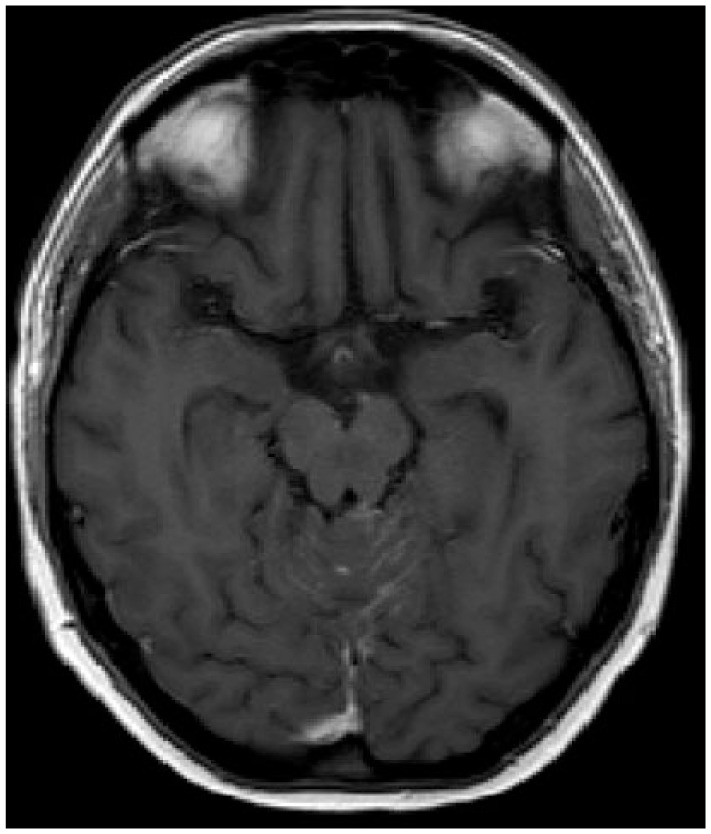

Figure 3.

Linear enhanced lesions in cerebellar foliae.

The LANO Group recommends for clinical trials that measurable lesions are defined as nodules of at least 5 × 10 mm in the orthogonal diameters and should be distinguished from linear contrast enhancement. Up to five target lesions (either measurable or not measurable) are selected at the baseline and must be monitored during the follow up. Based on the current recommendations, response determination in NM is as follows: completely resolved (+3), definitely improved (+2), possibly improved (+1), unchanged (0), possibly worse (−1), definitely worse (−2), new site of disease (−3). An increase of over 25% in a measurable lesion compared with the baseline is necessary to declare a progressive disease; similarly, a decrease of over 50% in a measurable lesion is considered as a partial response. The complete disappearance of a lesion is classified as complete response. All other situations are considered as stable disease. Changes of the ventricular volumes are not considered in the response assessment as well as the use of corticosteroids, which only modestly affect neurological improvement or MRI enhancement in NM from solid tumors. Conversely, the oncolytic effect of steroids in hematologic cancers is well known and thus steroid dose is included in the response criteria.2

The EANO/ESMO Group has proposed a classification of the radiological findings in NM: linear leptomeningeal disease (type A), nodular leptomeningeal disease (type B), both linear and nodular leptomeningeal disease (type C), absence of enhanced lesions but presence of hydrocephalus (type D)

CSF analysis

Several alterations may be found in the CSF of patients with NM, and include increased pressure (>200 mm H20) in 21–42% of patients, elevated leucocyte count (>4/mm3) in 48–77.5%, high level of proteins (>50 mg/dl) in 56–91% and decreased level of glucose (<60 mg/dl).10–37 Moreover, an increased level of lactate dehydrogenase (>1.6 mEq/liter) may be detected, while the presence of oligoclonal bands indicates an intrathecal immune activation.38 All these findings are not pathognomonic of NM, and the identification of malignant cells in the CSF remains the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis.

CSF cytology is usually a qualitative analysis with low sensitivity, and up to 30–50% of patients have a negative CSF.39 If the first CSF analysis is negative, a second or third lumbar puncture should be carried out with an increase of sensitivity to 80%.3 Notably, some factors may impact the yield of CSF cytology, such as volume of CSF (at least 10 ml), site of sample collection (that should be close to the neuroimaging alterations), and time to process CSF (within 30 min).31,40

Overall, the interpretation of CSF cytology, according to the LANO Group recommendations, is as follows: positive: unequivocal presence of neoplastic cells; equivocal: presence of ‘atypical’ or ‘suspicious’ cells; negative: absence of neoplastic cells.

A critical point is the duration of response following antineoplastic treatments: importantly, to declare a cytological response, CSF must be cleaned of tumor cells and maintain the status for at least 4 weeks, and other parameters, such as proteins, cell count and glucose level, are not taken into consideration for the evaluation of response.

Based on these criteria, progressive disease is defined by either conversion of negative to positive CSF cytology or failure to convert positive cytology to negative (refractory disease) following induction therapy.

The role of CSF FC in diagnosis of NM from solid tumors is limited, as reported by the LANO Group guidelines. In this regard, there is not a standard CSF FC diagnostic test to distinguish neoplastic cells from reactive pleocytosis in cases of doubtful morphology on conventional CSF cytology.41 Conversely, the CSF FC is a highly sensitive quantitative analysis for the diagnosis of NM hematologic malignancies as it may allow a more objective determination of tumor burden42 and predict the risk of CNS relapse.43,44

Recently, the EANO/ESMO Group provided recommendations considering both CSF and neuroimaging findings.3 The aim was twofold: to provide standardized diagnostic criteria and treatment response parameters shared by all clinicians; and to enroll in clinical trials patients who fulfill prespecified inclusion criteria.

Future directions in the CSF diagnosis

The liquid biopsy could be a new approach for an early diagnosis and monitoring of NM. Genomic profiles of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in the CSF have been shown to closely match those of the corresponding tumors.45 CSF samples from patients diagnosed with NM have been analyzed for the expression of epithelial cell adhesion molecules (EpCAM) to identify the CTCs. The prognostic value of FC immunophenotyping was evaluated in 72 patients diagnosed with NM and eligible for therapy.46 Compared with cytology, FC immunophenotyping had greater sensitivity and negative predictive value (80% versus 50% and 69% versus 52%, respectively), but lower specificity and positive predictive value (84% versus 100% and 90% versus 100%, respectively). Moreover, the multivariate analysis revealed that the percentage of CSF EpCAM-positive cells predicted an increased risk of death. In another study, EpCAM-based FC showed 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity rates in detecting NM compared with a sensitivity rate of 61.5% for cytology.47 This study may overestimate the accuracy: in fact, other studies reported lower sensitivity and specificity rates.48–50 Cordone and coworkers reported the successful use of CSF FC in detecting the overexpression of MUC-1 (CD227) and syndecan-1 (CD138), which are strongly correlated with CSF dissemination from breast cancer. Considering the small sample size, validation in a large cohort of patients is needed to confirm these results.51 Overall, the results suggest that CSF FC warrants further investigation for diagnosing NM. A further improvement in diagnosis is the Rare Cell Capture Technology (RCCT) for detecting and numbering CTCs in the CSF: Lin and colleagues defined at least one CSF-CTC/ml as the optimal cutoff for a robust diagnosis of NM.52

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has also been the objective of investigations in terms of liquid biopsy for brain tumors. There are some technical challenges associated with the use of ctDNA in CSF or serum as biomarkers due to the low concentration of nucleic acid in biofluids compared with cells. Some data suggest that ctDNA derived from metastatic lesions in the brain with clinical features of meningeal carcinomatosis is more abundant in the CSF compared with blood, thus CSF likely represents a preferable source of representative liquid biopsy in NM.53 Several techniques, such as microarrays,54 real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and whole exome sequencing,55–57 have displayed good sensitivity to find genomic alterations in the CSF, but it remains unclear what the cutoff is of tumor DNA in CSF that corresponds to clinically relevant NM. Additional studies are needed to compare ctDNA and cytology in the CSF from patients with NM, but these two approaches will probably complement the use of neuroimaging and clinical parameters.58,59

Exosomes are lipid-bilayer-enclosed extracellular vesicles, containing miRNAs, proteins, and DNAs, and secreted by cells and circulating in the blood. Cancer exosomes can function as intercellular messengers delivering protumor signals which contribute to mediate tumor metastasis.60,61 The isolation of cancer exosomes from patients with cancer remains a challenge, owing to the lack of specific markers that can differentiate cancer from noncancer exosomes. Melo and colleagues provided evidence that glypican 1 (GPC1) may serve as a pan-specific marker of cancer exosomes, thus GPC1 may be an attractive candidate for detection and isolation of exosomes in the serum of patients with cancer for genetic analysis of specific alterations.62

The use in clinical practice of CSF biomarkers, including B-glucoronidase, lactate dehydrogenase, B2-microglobulin, cancer antigen (CA) 15.3, CA 125, CA 19.9, α-fetoprotein (AFP), neuron-specific enolase, or molecules thought to be involved in the metastatic process, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, tissue plasminogen activator, metalloprotease, cathepsins and chemokines, have a limited role.

Differential diagnosis

Various non-neoplastic entities must be considered in order to confirm a diagnosis of a NM. Meningitis due to bacterial Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae or agalactiae, Listeria monocytogenes, Borrelia burgdorferi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, or viral meningitis due to herpes virus, Morbillivirus, Paramyxovirus, arbovirus, HIV-associated opportunistic CNS infections, or fungal meningitis due to Candida, Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces and Coccidioidies must be ruled out with CSF examination with specific cultures or PCR sequencing.

Several systemic inflammatory diseases may mimic the leptomeningeal enhanced lesions that are found in NM: vasculitis (Kawasaki disease, Takayasu arteritis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener granulomatosis, microscopic polyarteritis nodosa), systemic connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome), inflammatory bowel diseases and neurosarcoidosis. Finally, infectious or chemical meningitis need to be excluded following surgery or intrathecal treatments (baclofen), respectively.

Treatment

General considerations

Treatment goals in NM are to improve neurological symptoms with an acceptable quality of life and prolong survival. Only six randomized clinical trials have been conducted so far.26 Hence, the current management of NM is based on expert opinions and varies widely across Europe.57 Treatment options for NM include intrathecal chemotherapy, systemic chemotherapy and RT. It is not well known how much the systemic chemotherapy may cross the BBB and reach NM lesions, especially when the leptomeningeal spread is not yet accompanied by BBB dysfunctions.63 However, targeted therapies can prolong survival of patients with NM10,64,65 in patients with NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations or ALK rearrangement, and in patients with breast cancer harboring HER2 amplification.

Radiotherapy

To date, there is a lack of randomized clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of RT in NM. A retrospective analysis of NM from solid tumors (73 patients) and hematologic malignancies (62 patients) suggested no positive effect of RT in terms of survival, while systemic chemotherapy was associated with longer OS compared with local treatments modalities.66 Based on this background, RT does not represent the first line of treatment in NM. Focal RT, such as involved field or stereotactic RT or radiosurgery, should be considered for local, circumscribed and symptomatic lesions. RT has been proposed to resolve CSF flow obstructions in patients with spinal or intracranial blocks in order to improve the distribution of intra-CSF therapy.67 Typical targets for RT are cranial nerves of the skull base, interpeduncular cisterns, cervical vertebrae and lumbosacral segments in the case of cauda equine syndrome.

Whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) may be considered as a palliative treatment in patients with symptomatic extensive nodular or linear NM. Craniospinal RT is not recommended because of the poor benefit and the significant risk of developing severe adverse effects (myelotoxicity, enteritis and mucositis).

Intrathecal chemotherapy

Intrathecal treatment offers the advantage of a local therapy with minimum systemic toxicity. Although high drug concentrations can be achieved in the CSF, intrathecal treatment is not effective for bulky disease in the meninges because intra-CSF agents penetrate only 2–3 mm into such lesions.68 Chemotherapy administration can be performed either via lumbar puncture or via an intraventricular device with a catheter into the lateral ventricle and an Ommaya reservoir. The safety of ventricular devices has been shown in several series, but the management of the device could be difficult, and careful handling is required to avoid infections or obstruction.69

Three drugs are commonly used for the intrathecal treatment of NM: methotrexate (MTX), cytarabine (Ara-C) and thioTEPA. Different schedules have been proposed without any consensus on optimal dose, frequency of administration, or duration of treatment. Most patients are treated until progression and no advantage in terms of radiological control of the disease has been reported when comparing the three drugs.70,71 Due to the short half life of MTX, Ara-C, and thioTEPA (range 4.5–8.0 h), multiple weekly injections are necessary to maintain cytotoxic CSF level. In this regard, liposomal cytarabine (median half life 336 h) every 14 days may provide longer time to neurological progression compared with patients treated with MTX,71 and reduce the discomfort for patients of multiple lumbar punctures.

There is some clinical evidence that intrathecal chemotherapy may improve disease control and survival in NM from solid tumors, especially in patients with favorable prognostic factors, such as younger age (<55 years), absence of systemic metastases or cranial nerve involvement, normal value of CSF glucose and proteins. Moreover, the treatment response seems to be more dependent on the pretreatment patient characteristics than on the type of treatment.72 Overall, the evidence of the efficacy of intrathecal therapy is low and a careful evaluation of clinical factors helps clinicians to identify the subgroups of patients who may benefit.

The combination of intrathecal liposomal cytarabine and systemic chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer and NM is addressed in an ongoing trial [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01645839].

Systemic chemotherapy

Neoplastic meningitis from non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) occurs in 3.8% of patients, especially in the adenocarcinoma subtype. Combined platinum-based regimens with pemetrexed are the first-line treatment in BM, but the ability to reach adequate CSF concentrations and the efficacy in NM seems poor.73

Some driver mutations, such as EGFR mutations (11% of white patients with NSCLC) and ALK rearrangements (5% of NSCLC)74 may be targeted by specific inhibitors with encouraging data regarding disease control. The presence of EGFR mutations is an early step during carcinogenesis in NSCLC, and both BM and leptomeningeal dissemination are more common in patients with EGFR mutation compared with those who are EGFR wild type .75,76 Liao and colleagues have shown the efficacy of the first-generation EGFR TKI compounds, such as erlotinib and gefitinib, in NM from patients with EGFR mutation and longer OS (10.9 months versus 2.3 months).77 However, a low level (1–3%) of EGFR TKIs can be found in the CSF, suggesting an inability to adequately penetrate the BBB. Thus, higher doses of either erlotinib78 or gefitinib79 have been administered in order to achieve adequate therapeutic concentrations, reporting a neurological improvement in 57% and 50% of NM, and modest benefit in terms of median OS (3.5 months versus 6.2 months). Moreover, erlotinib has shown higher CSF concentrations (28.7 versus 3.7 ng/ml)80 and cytologic conversion rates (64.3% versus 9.1%)81 compared with gefitinib. Despite no improvement in OS, high doses of erlotinib have been suggested as palliative care to control neurological symptoms from NM.

Afatinib is an irreversible second-generation EGFR TKI that has demonstrated a good profile of efficacy in NM or BM in patients whose condition has failed to respond to first-line TKIs. Overall, 35% of patients achieved a radiological response, but the study did not distinguish the outcome between BM and NM.82 Notably, the penetration rate of afatinib in the CSF is 1.65% with a significant efficacy in patients with uncommon EGFR mutations, such as exon 18 mutations.83

From 49% to 63% of patients with NSCLC developed resistance to first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs due to the presence of a threonine-methionine substitution at position 790 (T790M) in exon 20. In this regard, osimertinib (AZD9291), a third-generation EGFR TKI, has shown greater penetration and better control of the extra cranial disease,84 while an ongoing phase II trial [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT0222-8369] with this drug is enrolling T790M-positive patients with NSCLC and NM.

A new promising therapeutic option is represented by AZD3759, a novel EGFR TKI with an excellent BBB penetration which is active against EGFR mutations, with the exception of T790M mutation. The efficacy and tolerability of AZD3759 have been investigated in 29 patients in the BLOOM trial. Of the four patients with NM who were enrolled, three displayed a significant reduction of EGFR expression on the cell surface, and one patient had a CSF conversion in two consecutive samples.85

In animal models the anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) A agent bevacizumab prevents the formation of NSCLC brain metastases.86 Based on this background, some phase II trials have reported an improved OS with the combinations erlotinib–bevacizumab87 and gefitinib–bevacizumab,88 and an ongoing clinical trial [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02803203] is now evaluating the efficacy of osimertinib–bevacizumab in NM from NSCLC.

ALK rearrangement is found in only 4–5% of patients with NSCLC and CNS is a relapse site in 35–50% of patients. NM in patients with ALK-positive NSCLC tends to appear later on (approximately 9 months from the diagnosis of NSCLC), suggesting that it is a late complication.89

Two randomized phase II trials have reported a major benefit from the first-generation ALK inhibitor crizotinib in terms of disease control in BM of patients with ALK mutation,89,90 but the efficacy is still controversial in NM due to the poor CNS penetration.

The second-generation ALK inhibitors, including ceritinib and alectinib, have been approved for the treatment of patients who are ALK positive, who were resistant to crizotinib. The phase II ASCEND-2 trial has demonstrated the efficacy of ceritinib in BM,91 and another phase II open-label study focused on ceritinib in patients with ALK-positive NSCLC metastatic to the brain or leptomeninges is ongoing (ASCEND-7) [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02336451]. In a mouse model, ceritinib was shown to be transported out of the brain by ABCB1 protein (ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1),92,93 while alectinib demonstrated low levels in the CSF. A recent phase III trial (ALEX study) has shown the superiority of alectinib compared with crizotinib for treating BM and protecting for subsequent brain relapse.94

Secondary ALK kinase domain mutations, including the recalcitrant G1202R mutation, have been identified in patients whose disease progressed on ceritinib or alectinib after crizotinib therapy. Brigatinib, an investigational next-generation ALK TKI, was designed for the potent activity against a broad range of ALK resistance mutations.95 Recently, Kim and collaborators reported some benefits in terms of radiological response (54%) and median PFS (12.9 months) following brigatinib in 154 BM from crizotinib-refractory ALK-positive NSCLC.96 However, there are no data available in NM.

Lorlatinib is a new third-generation ALK inhibitor, designed specifically to improve CNS penetration in crizotinib-resistant patients.97 A phase I trial of 54 patients has demonstrated impressive disease control in patients with ALK- and ROS1-positive NSCLC and BM; to date, an ongoing phase II trial [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01970865] is evaluating the activity of lorlatinib in both BM and NM.

Some preliminary data are available regarding the efficacy and tolerability in BM of immunotherapy, including anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) compounds, such as nivolumab,98 pembrolizumab,99 or the anti-PD ligand 1 atezolizumab,100 but there are no data in NM.

A new attractive therapeutic option is the oligodeoxynucleotide containing unmethylated cytosineguanosine motifs (CpG-ODN), that may activate both the innate and the adaptive immune system through toll-like receptor 9 (TLR-9).101 CpG-28 (TLR-9 agonist) may induce tumor reduction, especially when inoculated directly into the tumor in experimental models.102,103 Based on this background, a phase I trial was designed to define the safety profile of CpG-28 in 29 patients with NM from different metastatic tumors, including NSCLC. CpG-28 was well tolerated both subcutaneously and intrathecally. Interestingly, the median OS was slightly higher in eight patients who were concurrently treated with bevacizumab, but the difference was not statistically significant (19 weeks versus 15 weeks).104

Neoplastic meningitis from breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most frequent cause of NM from solid tumors, with an estimated frequency of 3–5%. Capecitabine has shown long-lasting responses in NM in small case series,105 and the use of an intensified regimen, such as metronomic schedule, has been proposed to treat NM from breast cancer, and is planned to be investigated in a larger phase II trial.106

Amplification of HER2 is observed in 15–20% of patients with breast cancer. Although HER2 is not identified as a risk factor in NM, brain metastases occur more frequently in HER2-positive breast cancer. Since trastuzumab does not easily cross the BBB, intrathecal trastuzumab has been investigated. Few reports in the literature have described clinical and radiological responses following intrathecal trastuzumab.107–109 Seventeen patients, who were administered intrathecal trastuzumab, displayed a significant neurological improvement and a CSF conversion in 66.7%, a PFS of 7.5 months and a median OS of 13.5 months,110 suggesting that intrathecal trastuzumab could be a feasible therapeutic option.

Lapatinib is a HER1–2 TKI that plays a significant role as a second-line treatment in BM from HER2-positive breast cancer following trastuzumab failure.111 A single-arm phase II trial (LANDSCAPE) has shown the activity of the combination of lapatinib and capecitabine as a first-line treatment in brain metastases from HER2-positive breast cancer.112 Conversely, no significant differences between capecitabine plus lapatinib versus capecitabine plus trastuzumab were observed in terms of incidence of CNS metastases as first site of relapse.113 Lavaud and coworkers suggested that high doses of oral lapatinib may be more effective than other intrathecal drugs, but this hypothesis needs to be further investigated in larger series.114

Neratinib is an irreversible inhibitor of HER2, erbB4 and EGFR with increased ability to cross an intact BBB and is unaltered by ABCB1-B2 transporters. However, the activity on BM does not seem superior over that of lapatinib.115

Finally, there are no data available on the efficacy and safety of lapatinib, neratinib, trastuzumab emtansine, or pertuzumab in NM from HER2-positive breast cancer.

Neoplastic meningitis from melanoma

Traditional chemotherapies, including temozolomide or nitrosoureas (dacarbazine and fotemustine), have limited efficacy in BM or NM from melanomas. Checkpoint inhibitors, such as nivolumab,116 ipilimumab,117 and pembrolizumab,118 alone or in combination with other treatments, have changed the prognosis of metastatic melanomas achieving a median OS ranging from 7.5 months to 22.7 months.119 A similar trend was observed with BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) and MEK inhibitors (trametinib) in BM from melanomas with a surprisingly OS of more than 5 years.120

Few case reports are present in the literature regarding the efficacy of vemurafenib in NM from melanomas.121,122 However, vemurafenib has a limited penetration of the BBB, suggesting a low chance to control the NM disease.123

Conclusion

NM from solid tumors is an emerging complication with no effective therapies. Great efforts have been made to provide standardized diagnostic criteria and methods of response evaluation for patients with NM, which require further testing and validation. Similarly, promising new techniques may play a role in the early detection of NM. Finally, randomized clinical trials with adapted methodology and new inclusion criteria are needed to better define the role of novel therapeutic options in NM.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Alessia Pellerino, Department of Neuro-Oncology, University and City of Health and Science Hospital, Via Cherasco 15, Turin, 10126 Italy.

Luca Bertero, Section of Pathology, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy.

Roberta Rudà, Department of Neuro-Oncology, University and City of Health and Science Hospital, Turin, Italy.

Riccardo Soffietti, Department of Neuro-Oncology, University and City of Health and Science Hospital, Turin, Italy.

References

- 1. Bruna J, Gonzalez L, Miro′ J, et al. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer 2009; 115: 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chamberlain M, Junck L, Brandsma D, et al. Leptomeningeal metastases: a RANO proposal for response criteria. Neuro Oncol 2017; 19: 484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le Rhun E, Weller M, Brandsma D, et al. EANO-ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with leptomeningeal metastasis from solid tumours. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(Suppl. 4): iv84–iv99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Groves MD. New strategies in the management of leptomeningeal metastases. Arch Neurol 2010; 67: 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kesari S, Batchelor TT. Leptomeningeal metastases. Neurol Clin 2003; 21: 25–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chamberlain MC. Leptomeningeal metastasis. Curr Opin Oncol 2010; 22: 627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lombardi G, Zustovich F, Farina P, et al. Neoplastic meningitis from solid tumors: new diagnostic and therapeutich approach. Oncologist 2011; 16: 1175–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chowdhary S, Damlo S, Chamberlain MC. Cerebrospinal fluid dissemination and neoplastic meningitis in primary brain tumors. Cancer Control 2017; 24: S1–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rudnicka H, Niwińska A, Murawska M. Breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis: the role of multimodality treatment. J Neurooncol 2007; 84: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee SJ, Lee JI, Nam DH, et al. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in non-small-cell lung cancer patients: impact on survival and correlated prognostic factors. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8: 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hastad L, Hess KR, Groves MD. Prognostic factors and outcomes in patients with leptomeningeal melanomatosis. Neuro Oncol 2008; 10: 1010–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abouharb S, Ensor J, Loghin ME, et al. Leptomeningeal disease and breast cancer: the importance of tumor subtype. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014; 146: 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Niwińska A, Rudnicka H, Murawska M, et al. Breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis: propensity of breast cancer subtypes for leptomeninges and the analysis of factors influencing survival. Med Oncol 2013; 30: 408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liao BC, Lee JH, Lin CC, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors for non-small-cell lung cancer patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10: 1754–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gainor JF, Ou SH, Logan J, et al. The central nervous system as a sanctuary site in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8: 1570–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2385–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roelz R, Reinacher P, Jabbarli R, et al. Surgical ventricular entry is a key risk factor for leptomeningeal metastasis of high grade gliomas. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 17758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ahn JH, Lee SH, Kim S, et al. Risk of leptomeningeal seeding after resection of brain metastases: implication of tumor location with mode of resection. J Neurosurg 2012; 116: 984–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson MD, Avkshtol V, Baschnagel AM, et al. Surgical resection of brain metastases and the risk of leptomeningeal recurrence in patients treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016; 94: 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gleissner B, Chamberlain MC. Neoplastic meningitis. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Ree TC, Dippel DW, Avezaat CJ, et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis after surgical resection of brain metastases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999; 66: 225–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conrad C, Dorzweiler K, Miller MA, et al. Profiling of metalloprotease activities in cerebrospinal fluids of patients with neoplastic meningitis. Fluid Barriers CNS 2017; 14: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mammoser AG, Groves MD. Biology and therapy of neoplastic meningitis. Curr Oncol Rep 2010; 12: 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lara-Medina F, Crismatt A, Villarreal-Garza C, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in patients with carcinomatous meningitis secondary to breast cancer. Breast J 2012; 18: 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chamberlain MC. Neoplastic meningitis: deciding who to treat. Expert Rev Neurother 2004; 4: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chamberlain M, Soffietti R, Raizer J, et al. Leptomeningeal metastastasis: a response assessment in neuro-oncology critical review of endpoints and response criteria of published randomized clinical trials. Neuro-Oncology 2014; 16: 1176–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh SK, Leeds NE, Ginsber LE. MR imaging of leptomeningeal metastases: comparison of three sequences. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002; 23: 817–821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh SK, Agris JM, Leeds NE, et al. Intracranial leptomeningeal metastases: comparison of depiction at FLAIR and contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 2000; 217: 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Straathof CS, de Bruin HG, Dippel DW, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and cerebrospinal fluid cytology in leptomeningeal metastasis. J Neurol 1999; 246: 810–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pauls S, Fischer AC, Brambs HJ, et al. Use of magnetic resonance imaging to detect neoplastic meningitis: limited use in leukemia and lymphoma but convincing results in solid tumors. Eur J Radiol 2011; 81: 974–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prömmel P, Pilgra-Pastor S, Sitter H, et al. Neoplastic meningitis: how MRI and CSF cytology are influenced by CSF cell count and tumor type. Sci World J 2013: 248072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clarke JL, Perez HR, Jacks LM, et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis in the MRI era. Neurology 2010; 74: 1449–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chamberlain MC. Comprehensive neuroaxis imaging in leptomeningeal metastasis: a retrospective case series. CNS Oncol 2013; 2: 121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nayak L, Fleisher M, Gonzalez-Espinoza R, et al. Rare cell capture technology for the diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastasis in slide tumors. Neurology 2013; 80: 1598–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grossman SA, Trump DL, Chen DC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid flow abnormalities in patients with neoplastic meningitis. An evaluation using 111indium-DTPA ventriculography. Am J Med 1982: 73: 641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Glantz MJ, Hall WA, Cole BF, et al. Diagnosis, management, and survival of patients with leptomeningeal cancer base on cerebrospinal fluid-flow status. Cancer 1995; 75: 2919–2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kwon J, Chie EK, Kim K, et al. Impact of multimodality approach for patients with leptomeningeal metastases from solid tumors. J Korean Med Sci 2014; 29: 1094–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weller M, Stevens A, Sommer N, et al. Tumor cell dissemination triggers an intrathecal immune response in neoplastic meningitis. Cancer 1992; 69: 1475–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jung H, Sinnarajah A, Enns B, et al. Managing brain metastases patients with ad without radiotherapy: initial lessons from a team-based consult service through a multidisciplinary integrated palliative oncology clinic. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21: 3379–3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Glantz MJ, Cole BF, Glantz LK, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid cytology in patients with cancer: minimizing false-negative results. Cancer 1998; 82: 733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bommer M, Nagy A, Schöpflin C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis: pitfalls and benefits of combined analysis using cytomorphology and flow cytometry. Cancer Cytopathol 2011; 119: 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rogers LR, Duchesneau PM, Nunez C, et al. Comparison of cisternal and lumbar CSF examination in leptomeningeal metastasis. Neurology 1992; 42: 1239–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nuckel H, Novotny J, Noppeney R, et al. Detection of malignant haematopoietic cells in the cerebrospinal fluid by conventional cytology and flow cytometry. Clin Lab Haematol 2006; 28: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hedge U, Fille A, Little RF, et al. High incidence of occult leptomeningeal disease detected by flow cytometry in newly diagnosed aggressive B-cell lymphomas at risk for central nervous system involvement: the role of flow cytometry versus cytology. Blood 2005; 105: 496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, et al. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017; 14: 531–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Subirá D, Simó M, Illán J, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of flow cytometry immunophenotyping in patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Clin Exp Metastasis 2015; 32: 383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Milojkovic Kerklaan B, Pluim D, Bol M, et al. EpCAM-based flow cytometry in cerebrospinal fluid greatly improves diagnostic accuracy of leptomeningeal metastases from epithelial tumors. Neuro Oncol 2016; 18: 855–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Spizzo G, Fong D, Wurm M, et al. EpCAM expression in primary tumour tissues and metastases: an immunohistochemical analysis. J Clin Pathol 2011; 64: 415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jiang BY, Li YS, Guo WB, et al. Detection of driver and resistance mutations in leptomeningeal metastases of NSCLC by next-generation sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid circulating tumor cells. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23: 5480–5488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Van Bussel MTJ, Pluim D, Bol M, et al. EpCAM-based assays for epithelial tumor cell detection in cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurooncol. Epub ahead of print 30 November 2017. DOI: 10.1007/s11060-017-2691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cordone I, Masi S, Summa V, et al. Overexpression of syndecan-1, MUC-1, and putative stem cell markers in breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis: a cerebrospinal fluid flow cytometry study. Breast Cancer Res 2017; 19: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lin W, Fleisher M, Rosenblum M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid circulating tumor cells: a novel tool to diagnose leptomeningeal metastases from epithelial tumors. Neuro Oncol 2017; 19: 1248–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Marchiò C, Mariani S, Bertero L, et al. Liquoral liquid biopsy in neoplastic meningitis enables molecular diagnosis and mutation tracking: a proof of concept. Neuro Oncol 2017; 19: 451–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Magbanua MJ, Roy R, Sosa EV, et al. Genome-wide copy number analysis of cerebrospinal fluid tumor cells and their corresponding archival primary tumors. Genom Data 2014; 2: 60–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li Y, Pan W, Connolly ID, et al. Tumor DNA in cerebral spinal fluid reflect clinical course in patients with melanoma leptomeningeal brain metastases. J Neurooncol 2016; 128: 93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shingyoji M, Kageyama H, Sakaida T, et al. Detection of epithelial growth factor receptor mutations in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with lung adenocarcinoma suspected of neoplastic meningitis. J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6: 1215–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. LeRhun E, Rudà R, Devos P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment patterns for patients with leptomeningeal metastasis from solid tumors across Europe. J Neurooncol 2017; 133: 419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bougel S, Lhermitte B, Gallagher G, et al. Methylation of the hTERT promoter: a novel cancer biomarker for leptomeningeal metastasis detection in cerebrospinal fluids. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19: 2216–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Samuel N, Remke M, Rutka JT, et al. Proteomic analyses of CSF aimed at biomarker development for pediatric brain tumors. J Neurooncol 2014; 118: 225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Syn N, Wang LZ, Sethi G, et al. Exosome-mediated metastasis: from epithelial-mesenchymal transition to escape from immunosurveillance. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2016; 37: 606–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Peinado H, Aleckovic M, Lavotshkin S, et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med 2012; 18: 883–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Melo SA, Luecke LB, Kahlert C, et al. Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015; 523: 177–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pardridge WM. CSF, blood-brain barrier, and brain drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2016; 13: 963–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Du C, Hong R, Shi Y, et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis from solid tumors: a single center experience in Chinese patients. J Neuro Oncol 2013; 115: 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Park JH, Kim YJ, Lee JO, et al. Clinical outcomes of leptomeningeal metastasis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer in the modern chemotherapy era. Lung Cancer 2012; 76: 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Oechsle K, Lange-Brock V, Kruell A, et al. Prognostic factors and treatment options in patients with leptomeningeal metastases of different primary tumors: a retrospective analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2010; 136: 1729–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chamberlain MC. Radioisotope CSF flow studies in leptomeningeal metastases. J Neurooncol 1998; 38: 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fleischhack G, Jaehde U, Bode U. Pharmacokinetics following intraventricular administration of chemotherapy in patients with neoplastic meningitis. Clin Pharmacokinet 2005; 44: 1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zairi F, Le Rhun E, Bertrand N, et al. Complications related to the use of an intraventricular access device for the treatment of leptomeningeal metastases from solid tumors: a single centre experience in 112 patients. J Neurooncol 2015; 124: 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Grossman SA, Finkelstein DM, Ruckdeschel JC, et al. Randomized prospective comparison of intraventricular methotrexate and thiotepa in patients with previously untreated neoplastic meningitis, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 1993; 11: 561–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Glantz MJ, Jaecle KA, Chamberlain MC, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing intrathecal sustained-release cytarabine (DepoCyt) to intrathecal methotrexate in patients with neoplastic meningitis from solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 1999; 5: 3394–3402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Boogerd W, Hart AA, van der Sande JJ, et al. Meningeal carcinomatosis in breast cancer. Prognostic factors and influence of treatment. Cancer 1991; 67: 1685–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Stapleton SL, Reid JM, Thompson PA, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of pemetrexed after intravenous administration in non-human primates. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2007; 59: 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Barlesi F, Mazieres J, Merlio JP, et al. Routine molecular profiling of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a 1-year nationwide programme of the French Cooperative Intergroup (IFCT). Lancet 2016; 387: 1415–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Matsumoto S, Takahashi K, Iwakawa R, et al. Frequent EGFR mutations in brain metastases of lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 2006; 119: 1491–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Li YS, Jiang BY, Yang JJ, et al. Leptomeningeal metastases in patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11: 1962–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Liao BC, Lee JH, Lin CC, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors for non-small-cell lung cancer patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10: 1754–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kawamura T, Hata A, Takeshita J, et al. High-dose erlotinib for refractory leptomeningeal metastases after failure of standard-dose EGFR-TKIs. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2015; 75: 1261–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Jackman DM, Cioffredi LA, Jacobs L, et al. A phase I trial of high dose gefitinib for patients with leptomeningeal metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 4527–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Togashi Y, Masago K, Masuda S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid concentration of gefitinib and erlotinib in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012; 70: 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lee E, Keam B, Kim DW, et al. Erlotinib versus gefitinib for control of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8: 1069–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hoffknecht P, Tufman A, Wehler T, et al. Efficacy of the irreversible ErbB family blocker afatinib in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)-pretreated non-small-cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases or leptomeningeal disease. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10: 156–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tamiya A, Tamiya M, Nishira T, et al. Efficacy and cerebrospinal fluid concentration of afatinib in NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation developing leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 8: 1245–1250. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Yang JCH, Kim DW, Kim SW, et al. Osimertinib activity in patients (pts) with leptomeningeal (LM) disease from non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): updated results from BLOOM, a phase I study. ASCO Meet Abstr 2016; 34: 9002. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ahn MJ, Kim DW, Kim TM, et al. Phase I study of AZD3759, a CNS penetrable EGFR inhibitor, for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with brain metastasis (BM) and leptomeningeal metastasis (LM). Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 3–7 June 2016, McCormick Place, Chicago, IL, USA, p. 9003. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ilhan-Mutlu A, Osswald M, Liao Y, et al. Bevacizumab prevents brain metastases formation in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther 2016; 15: 702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Seto T, Kato T, Nishio M, et al. Erlotinib alone or with bevacizumab as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (JO25567): an open-label, randomised, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1236–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ichihara E, Hotta K, Nogami N, et al. Phase II trial of gefitinib in combination with bevacizumab as first-line therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer with activating EGFR gene mutations: the Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group Trial 1001. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10: 486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gainor JF, Ou SHI, Logan J, et al. The central nervous system as a sanctuary site in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8: 1570–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Shaw AT, Janne PA, Besse B, et al. Crizotinib vs chemotherapy in ALK+ advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): final survival results from PROFILE 1007. ASCO Meet Abstr 2016; 34: 9066. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Crinò L, Ahn MJ, De Marinis F, et al. Multicenter phase II study of whole-body and intracranial activity with ceritinib in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy and crizotinib: results from ASCEND-2. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 2866–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Kort A, Sparidans RW, Wagenaar E, et al. Brain accumulation of the EML4-ALK inhibitor ceritinib is restricted by p-glycoprotein (P-GP/ABCB1) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2). Pharmacol Res 2015; 102: 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Tang SC, Nguyen LN, Sparidans RW, et al. Increased oral availability and brain accumulation of the ALK inhibitor crizotinib by coadministration of the P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) and breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) inhibitor elacridar. Int J Cancer 2014; 134: 1484–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Gilbert JA. Alectinib surpasses crizotinib for untreated ALK-positive NSCLC. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: e377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Huang WS, Liu S, Zou D, et al. Discovery of brigatinib (AP26113), a phosphine oxide-containing, potent, orally active inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase. J Med Chem 2016; 59: 4948–4964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kim DW, Tiseo M, Ahn MJ, et al. Brigatinib in patients with crizotinib-refractory anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized, multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 2490–2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Zou HI, Friboulet L, Kodack DP, et al. PF-06463922, an ALK/ROS1 inhibitor, overcomes resistance to first and second generation ALK inhibitors in preclinical models. Cancer Cell 2015; 28: 70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 123–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 1540–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Rittmeyer A, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Krieg AM, Efler SM, Wittpoth M, et al. Induction of systemic TH1-like innate immunity in normal volunteers following subcutaneous but not intravenous administration of CPG 7909, a synthetic B-class CpG oligodeoxynucleotide TLR9 agonist. J Immunother 2004; 27: 460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Carpentier AF, Xie J, Mokhtari K, et al. Successful treatment of intracranial gliomas in rat by oligodeoxynucleotides containing CpG motifs. Clin Cancer Res 2000; 6: 2469–2473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Carpentier A, Laigle-Donadey F, Zohar S, et al. Phase 1 trial of CpG ODN for patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2006; 8: 60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ursu R, Taillibert S, Banissi C, et al. Immunotherapy with CpG-ODN in neoplastic meningitis: a phase I trial. Cancer Sci 2015; 106: 1212–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Tanaka Y, Oura S, Yoshimasu T, et al. Response of meningeal carcinomatosis from breast cancer to capecitabine monotherapy: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2013; 6: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Maur M, Omarini C, Piacentini F, et al. Metronomic capecitabine effectively blocks leptomeningeal carcinomatosis from breast cancer: a case report and literature review. Am J Case Rep 2017; 18: 208–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Oliveira M, Braga S, Passos-Coelho JL, et al. Complete response in HER2+ leptomeningeal carcinomatosis from breast cancer with intrathecal trastuzumab. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 127: 841–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Dumitrescu C, Lossignol D. Intrathecal trastuzumab treatment of the neoplastic meningitis due to breast cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol Med 2013; 2013: 154674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Martens J, Venuturumilli P, Corbets L, et al. Rapid clinical and radiographic improvement after intrathecal trastuzumab and methotrexate in a patient with HER-2 positive leptomeningeal metastases. Acta Oncol 2013; 52: 175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Bartsch R, et al. Intrathecal administration of trastuzumab for the treatment of meningeal carcinomatosis in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 139: 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 2733–2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Bachelot T, Romieu G, Campone M, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with previously untreated brain metastases from HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (LANDSCAPE): a single-group phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Pivot X, Manikhas A, Zurawski B, et al. Cerebel (EGF111438): a phase III, randomized, open-label study of lapatinib plus capecitabine versus trastuzumab plus capecitabine in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 1564–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Lavaud P, Rousseau B, Ajgal Z, et al. Bi-weekly very-high-dose lapatinib: an easy-to-use active option in HER-2-positive breast cancer patients with meningeal carcinomatosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016; 157: 191–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Freedman RA, Gelman RS, Wefel JS, et al. Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium (TBCRC) 022: a phase II trial of neratinib for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer and brain metastases. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 945–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Callahan MK, Kluger H, Postow MA, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma: updated survival, response, and safety data in a phase I dose-escalation study. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Margolin K, Ernstoff MS, Hamid O, et al. Ipilimumab in patients with melanoma and brain metastases: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Anderson ES, Postow MA, Wolchok JD, et al. Melanoma brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery and concurrent pembrolizumab display marked regression; efficacy and safety of combined treatment. J Immunother Cancer 2017; 5: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Sloot S, Chen YA, Zhao X, et al. Improved survival of patients with melanoma brain metastases in the era of targeted BRAF and immune checkpoint therapies. Cancer 2018; 124: 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Long GV, Eroglu Z, Infante J, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with BRAF V600-mutant metastatic melanoma who received dabrafenib combined with trametinib. J Clin Oncol. Epub ahead of print 9 October 2017. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Floudas CS, Chandra AB, Xu Y. Vemurafenib in leptomeningeal carcinomatosis from melanoma: a case report of near-complete response and prolonged survival. Melanoma Res 2016; 26: 312–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kim DW, Barcena E, Mehta UN, et al. Prolonged survival of a patient with metastatic leptomeningeal melanoma treated with BRAF inhibition-based therapy: a case report. BMC Cancer 2015; 15: 400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Sakji-Dupre L, Le Rhun E, Templier C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of vemurafenib in patients treated for brain metastatic BRAF-v600 mutated melanoma. Melanoma Res 2015; 25: 302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]