Abstract

Objectives:

Poor immunological recovery in treated HIV-infected patients is associated with greater morbidity and mortality. To date, predictive biomarkers of this incomplete immune reconstitution have not been established. We aimed to identify a baseline metabolomic signature associated with a poor immunological recovery after antiretroviral therapy (ART) to envisage the underlying mechanistic pathways that influence the treatment response.

Design:

This was a multicentre, prospective cohort study in ART-naive and a pre-ART low nadir (<200 cells/μl) HIV-infected patients (n = 64).

Methods:

We obtained clinical data and metabolomic profiles for each individual, in which low molecular weight metabolites, lipids and lipoproteins (including particle concentrations and sizes) were measured by NMR spectroscopy. Immunological recovery was defined as reaching CD4+ T-cell count at least 250 cells/μl after 36 months of virologically successful ART. We used univariate comparisons, Random Forest test and receiver-operating characteristic curves to identify and evaluate the predictive factors of immunological recovery after treatment.

Results:

HIV-infected patients with a baseline metabolic pattern characterized by high levels of large high density lipoprotein (HDL) particles, HDL cholesterol and larger sizes of low density lipoprotein particles had a better immunological recovery after treatment. Conversely, patients with high ratios of non-HDL lipoprotein particles did not experience this full recovery. Medium very-low-density lipoprotein particles and glucose increased the classification power of the multivariate model despite not showing any significant differences between the two groups.

Conclusion:

In HIV-infected patients, a baseline healthier metabolomic profile is related to a better response to ART where the lipoprotein profile, mainly large HDL particles, may play a key role.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, biomarkers, HIV-1, metabolomics, poor immune recovery

Introduction

Since the introduction of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART), the fatal course of HIV infection has been prevented. ART decreases viral replication, increases CD4+ T-cell count and consequently, improves the immune system function [1]. On the contrary, 25–30% of HIV-infected patients still fail to restore their CD4+ T-cell number despite optimal treatment and sustained virological suppression [2]. This group of patients is referred to as ‘immunodiscordants’ or ‘immunological nonresponders’ (INR) and are at a higher risk of clinical progression and death [3].

Traditional factors associated with poor immune recovery are delayed diagnosis, advanced age, lower initial CD4+ cell count, injection drug use transmission, coinfection with hepatitis C virus (HCV), thymic dysfunction, immune activation and genetic factors among others [4–6]. However, none of them provides a full explanation of the lack of total immune reconstitution. In addition, no predictive biomarkers of this immunological recovery in HIV-infected patients are currently available.

In the current study, we used a comprehensive metabolomic approach to plasma samples from HIV-infected individuals before starting ART with the aim of identifying a ‘metabolomic signature’ that might predict immunological recovery measured after 36 months.

Metabolomics techniques such as NMR have emerged as a powerful method for discovering new biomarkers for disease diagnosis, prognosis and risk prediction. One of its most important advantages is that it can be used to identify disease-related patterns through accurate detection of numerous metabolic changes in biological samples [7,8].

Methods

Study design

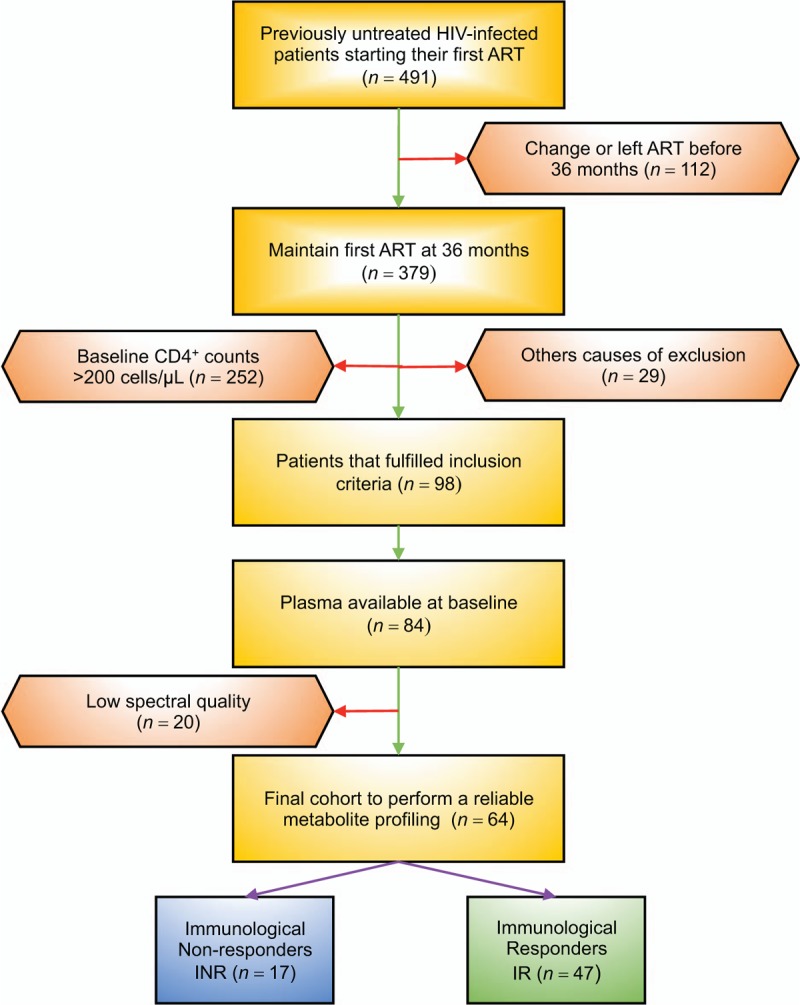

A multicentre, prospective cohort study comprising all adult HIV-1 infected individuals who started their first ART between 2009 and 2011 and were followed-up at the HIV outpatient clinics of the participating hospitals: Hospital Joan XXIII (Tarragona), Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona) and Hospital Virgen del Rocío (Sevilla). Of the initial cohort (n = 491), 379 maintained first ART during 36 months and achieved virological suppression after 6 months of starting ART; 252 were excluded because they had pre-ART CD4+ T-cell count more than 200 cells/μl. Therefore, 98 participants fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: more than 18 years, presence of HIV-1 infection and a pre-ART low nadir CD4+ T-cell count (<200 cells/μl). Exclusion criteria were HCV coinfection, the presence of active opportunistic infections, current inflammatory diseases or conditions, consumption of drugs with known metabolic effects (such as lipid-lowering agents), type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, acute or chronic renal failure, pregnancy, history of vaccination during the previous year, plasma C-reactive protein more than 1 mg/dl and adherence to ART lower than 90%, assessed through a standardized questionnaire [9]. From those patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, we handled a subset of 84 whose stored plasma samples, drawn when enrolled, were available. In a final step, we excluded 20 samples due to their poor spectral quality, caused by machine acquisition problems (bad water suppression and shimming inconsistencies), which resulted in a final cohort of 64 patients. Patients were categorized into two groups based on their CD4+ T-cell count at 36 months after ART: immunological responders group if their CD4+ T-cell count was equal or greater than 250 cells/μl or INR group if they did not reach this threshold [3,4]. Figure 1 provides a flow chart with patient selection and enrolment. The ethics committee from each recruiting centre reviewed and approved the study protocol, and all participants provided their written informed consent.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the patients included in the study.

Other causes of exclusion include hepatitis C virus coinfection, the presence of active opportunistic infections, current inflammatory diseases or conditions, consumption of drugs with known metabolic effects, type 2 diabetes mellitus, acute or chronic renal failure, pregnancy, history of vaccination during the previous year and plasma C-reactive protein more than 1 mg/dl.

Data collection

Relevant clinical and demographic data were extracted from an electronic predefined database specially defined for this study. Fasting venous blood samples were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes and centrifuged immediately for 15 min at 4 °C and 1500 × g. Plasma samples were then stored at −80 °C until further analysis at the BioBanc IISPV following standard operation procedures and with appropriate approval of the Ethical and Scientific Committees.

Procedures

In addition to NMR spectroscopy using the Liposcale test (a total set of 26 variables), we measured lipid concentrations (i.e. triglycerides and cholesterol), sizes and particle numbers for very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (38.6–81.9 nm), low density lipoprotein (LDL) (18.9–26.5 nm) and high density lipoprotein (HDL) classes (7.8–11.5 nm), as well as the particle numbers of nine subclasses, namely large, medium and small VLDL, LDL and HDL of frozen EDTA plasma specimens [10]. This test was based on two-dimensional spectra from diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY) experiments. Briefly, cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations of the main lipoprotein fractions were predicted using partial least squares regression models. Then, the methyl proton resonances of the lipids in lipoprotein particles were decomposed into nine Lorentzian functions representing nine lipoprotein subclasses and the mean particle size of every main fraction (VLDL, LDL and HDL) was derived by averaging the NMR area of each fraction by its associated size. Finally, we calculated the particle numbers of each lipoprotein main fraction by dividing the lipid volume by the particle volume of a given class and we used the relative areas of the lipoprotein components used to decompose the NMR spectra to derive the particle numbers of the nine lipoprotein subclasses.

A target set of eleven low molecular weight metabolites (LMWMs) was identified and quantified by NMR spectroscopy in the 1D Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill sequence (CPMG) spectra using Dolphin [11,12]. Each metabolite was identified by checking for all its resonances along the spectra, and then quantified using line-shape fitting methods on one of its signals. The quantification units corresponding to the area under the curve (AUC) of each metabolite were normalized by the mean of each of them throughout all samples, the final units being a reflection of the fold change of each sample over the mean of the dataset. In addition to this set, we incorporated the measure of a peak related with glycoprotein concentration in blood [13] and the quantification of two EDTA peaks that have been reported previously to be indicators of calcium and magnesium levels in blood [14].

All 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 310 K on a Bruker Avance III 600 spectrometer (Bruker, GmbH, Silberstreifen, Rheinstetten, Germany) operating at a proton frequency of 600.20 MHz and using a 5-mm triple resonance (1H, 13C, 31P) gradient cryoprobe (CPTCI).

Detailed information on the technical details of the NMR spectra pulse acquisition programs (CPMG and DOSY) and sample preparation can be found in Supplemental Digital Content (Supplemental Digital Content S1).

Statistical analyses

All data were tested for normality using Shapiro–Wilk test. A descriptive analysis of patients’ characteristics was carried out using frequency tables for categorical variables and median and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between INR and immunological responder groups were assessed through the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables and the Chi-squared test for independence for categorical variables.

To find metabolic differences between the two groups, we compared their metabolic patterns at baseline using different methods. Univariate comparisons were made through the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. P value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. In addition, the fold change of each variable was calculated as A/B, where A was the variable median in the immunological responders group and B was the variable median in the INRs group. Multivariate statistics were also used to improve the refining and distilling of all the metabolic baseline data and for pattern recognition purposes. In this sense, Random Forest analysis was applied, which is a supervised classification technique based on an ensemble of decision trees and provides an unbiased selection of variables that make the largest contributions to the classification. For this analysis, apart from the metabolic variables, the variables of age and CD4+ T-cell count at baseline were included to evaluate their importance as predictors in the classification between the two groups. Finally, logistic regression analysis and receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated, using as input those metabolites considered important discriminators of CD4+ T-cell recovery, obtained from the Mann–Whitney U test (P values <0.05) and the Random Forest analysis (largest contributions in the classification model) and adjusted for confounders (age and baseline CD4+ T-cell count). The statistical software used included the program ‘R’ (http://cran.r-project.org) and the SPSS 21.0 package (IBM, Madrid, Spain).

Results

After 36 months, 17 of 64 individuals (27%) failed to arrive at 250 CD4+ T-cell count/μl, whereas 47 of 64 (73%) reached this threshold. Table 1 contains baseline clinical details of the two subsets analysed. The differences in age and baseline CD4+ T-cell count between groups, despite not being statistically significant, were in agreement with the literature [4,5], suggesting that older people with a low nadir CD4+ T-cell count are associated with a lower recovery capacity.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical details.

| Study cohort, n = 64 | |||

| Variable | INR, n = 17 | IR, n = 47 | P value |

| Age (years) | 44 (39–55) | 38 (34–50) | 0.075 |

| Male (%) | 76.5 | 78.7 | 1.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.9 (21.5–23.4) | 23 (20.8–24.2) | 0.967 |

| AIDS (%) | 100.0 | 85.1 | 0.175 |

| HIV-1 risk factor (%) | |||

| Injecting drug user | 0.0 | 8.5 | 0.566 |

| Homosexual | 47.1 | 44.7 | 1.000 |

| Heterosexual | 41.2 | 42.6 | 1.000 |

| Other/unknown | 11.8 | 4.3 | 0.285 |

| CD4+ T-cell count (cells/μl) | |||

| Baseline | 60 (28–122) | 92 (48–166) | 0.068 |

| At 36 months after ART | 188 (117–219) | 378 (323–469) | <0.001 |

| Plasma viral load (log copies/ml) | |||

| Baseline | 5.5 (4.8–5.7) | 5.4 (4.8–5.7) | 0.915 |

| At 36 months after ART | 1.3 (1.3–1.7) | 1.3 (1.3–1.6) | 0.355 |

| ART received (%) | |||

| 2NRTi + NNRTi | 47.1 | 42.6 | 0.782 |

| 2NRTi + PI | 52.9 | 57.4 | 0.782 |

Quantitative variables are expressed as median (interquartile range). Qualitative variables are expressed as percentages. AIDS was diagnosed according to the CDC1993 criteria. ART, antiretroviral treatment; INR, immunological nonresponders; IR, immunological responders; NRTi, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTi, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PI, protease inhibitors.

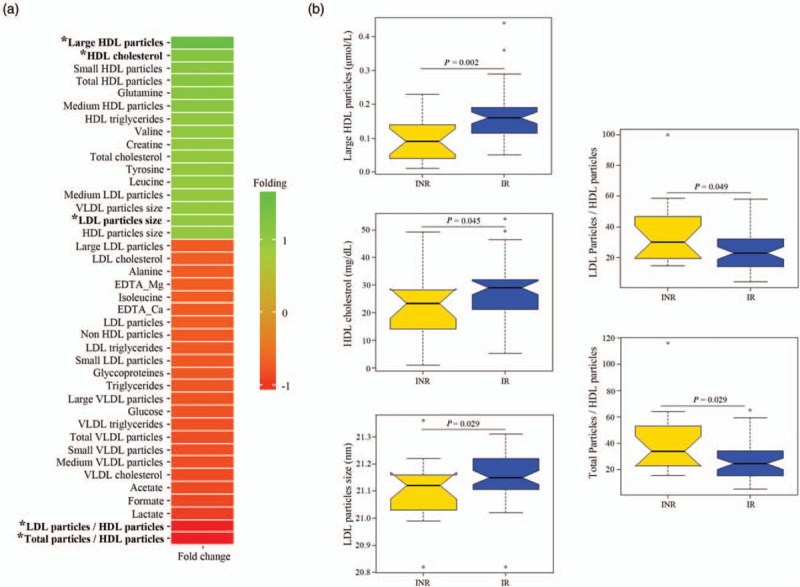

Figure 2a shows a heat map of the fold change of the 40 metabolomic variables used in this study. According to the fold change analysis, all HDL particles, including HDL cholesterol and HDL triglycerides, were increased in the immunological responders group at baseline point, whereas all VLDL particles, including VLDL cholesterol and VLDL triglycerides, and almost all LDL particles, including LDL cholesterol and LDL triglycerides, were higher in the INR group. This particle balance makes ‘LDL particles/HDL particles’ and ‘Total particles/HDL particles’ the most increased variables in the INR group at the baseline point. The size of all kinds of particles (HDL, LDL and VLDL) was higher in the immunological responders group. From the LMWM balance, the immunological responders group presented higher concentration of most of the amino acids (histidine, glutamine, valine, creatine, tyrosine and leucine), whereas the INR group showed greater concentration of a few (alanine and isoleucine). All acids (lactate, formate and acetate), the two EDTA peaks, the glycoprotein peak and glucose were lower in the immunological responders group. Figure 2b presents the notched box-plots of the five metabolomic variables significantly altered at baseline point between groups. Large HDL particles (P = 0.002), LDL particle size (P = 0.029) and HDL cholesterol (P = 0.045) were all significantly higher in immunological responders group, whereas ratios of total particles/HDL particles (P = 0.029) and LDL particles/HDL particles (P = 0.049) were higher in INR group. The univariate results therefore suggest that high levels of HDL particles (especially the subclass ‘large’) including HDL cholesterol and larger LDL particle sizes favoured immunological recovery. On the other hand, high ratios of lipid particles, where HDL particles were the denominator, did not.

Fig. 2.

Univariate analysis of measured metabolomic variables at baseline.

(a) Fold-change heat map of the relative plasma concentrations of measured metabolites at baseline. Positive folding (green) means higher concentrations in the responders group, whereas negative folding (red) means the opposite. The asterisk highlights those variables with a significant P value able to distinguish responders and nonresponders HIV-patients. (b) Notched box-plots of statistically significant altered metabolites, where the notch shows the 95% confidence interval for the median, given by m ± 1.58 × IQR/√n. IQR, interquartile range; out-of-bag (OB) error.

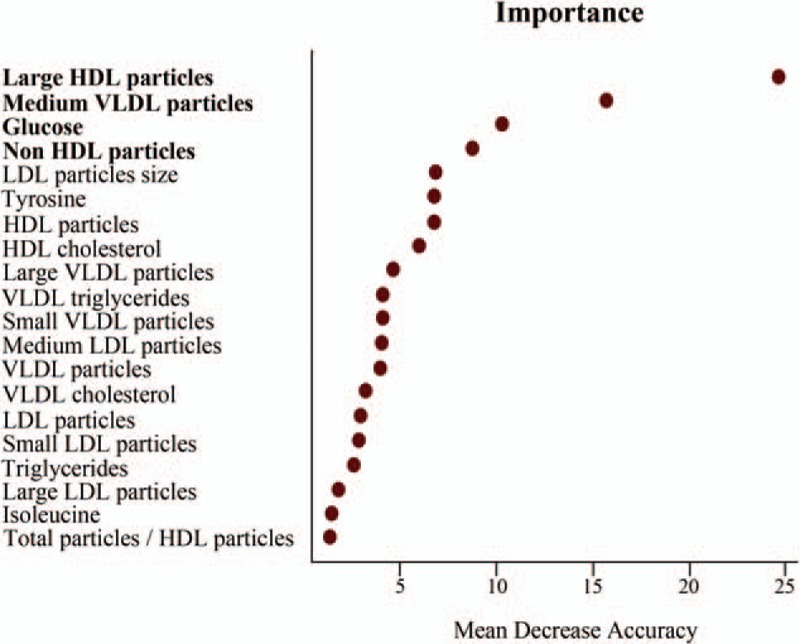

Random Forest analysis revealed large HDL particles as the primary differentiator in a ranked list of metabolites in order of their importance in the classification scheme (Fig. 3). It is important to highlight that large HDL particles were also the most significant variable in the univariate test, which suggested that they are a powerful pre-ART indicator of CD4+ T-cell recovery over time. The next three variables in order of importance were medium VLDL particles, glucose and all non-HDL particles, which despite not being significantly different in the univariate analysis had strong classification power in the multivariate model, and thus were selected for the logistic regression and ROC analyses.

Fig. 3.

Variable importance plot of the Random Forest analysis resulting from a large number of models built around immunological response to antiretroviral therapy.

The variables are ordered top-to-bottom as most-to-least important in classifying between responders and nonresponders. The ranked list of variables tells us the importance of each variable in classifying data (OB error = 24%). The figure shows the top 20 variables in importance of classification from a total of 42, including age and CD4+ T-cell count, and only the top four (bold) were considered for the receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis.

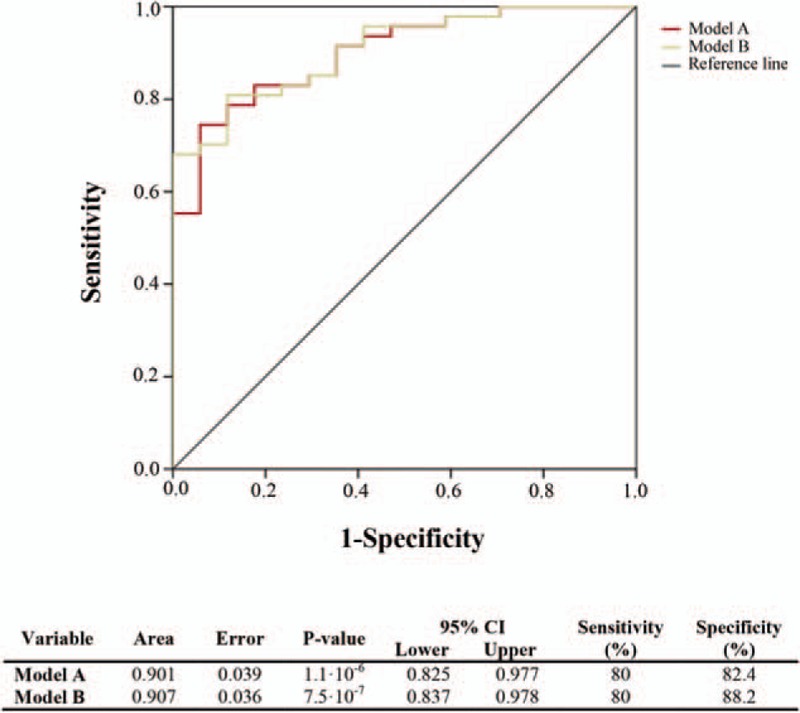

Finally, we evaluated the potential clinical usefulness of our highlighted metabolomic candidates. Accordingly, the ROC curve revealed the diagnostic accuracy of this metabolomic signature, obtained in the Mann–Whitney and the Random Forest analyses. Our results showed that the AUC of each analyte was less than 0.8 (Supplemental Digital Content S2). For this reason, we used a multivariate logistic regression model that combined each potential biomarker mentioned before. This model displayed an AUC value of 0.901 and correctly classified 84.4% of patients with 80% of sensitivity and 82.4% specificity (Fig. 4, Model A). Moreover, given that age and baseline CD4+ T-cell count are considered confounders, we did an adjusted analysis. In this case, the AUC value increased by only 0.006, specificity increased by 5.8% and it did not improve the percentage of classification (84.4%) (Fig. 4, Model B).

Fig. 4.

Using receiver-operating characteristic curves, we assessed multimetabolite biomarker models that could accurately predict a discordant response to HIV-infection treatment.

Model A inputs: large HDL particles, LDL particle size, total particles/HDL particles, LDL particles/HDL particles, glucose, medium VLDL particles and non-HDL particles. For Model B, we used the same metabolomic inputs but the model was adjusted for age and baseline CD4+ T-cell count. LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; VLDL, very-low-density lipoprotein.

Discussion

Our findings reveal that there are metabolomic differences between pre-ART HIV-infected individuals with a low nadir of CD4+ T-cell count at baseline and that these differences are associated with the future response after 36 months of treatment. In general, the immunological responders group presents a healthier metabolomic profile than the INR group. Even considering that only five metabolomic indicators significantly altered in the univariate test, the fold change of all kinds of HDL particles and the size of all the lipoprotein classes were higher in the immunological responders group, whereas all kinds of VLDL and most LDL particles were higher in the INR group. Moreover, the Random Forest test corroborated that large HDL particles and LDL particle size are key metabolomic features that differentiate immunological responders and INR. This test also showed that medium VLDL and non-HDL particles, despite not being significantly different between groups, contribute to that. Putting all of these factors together, we report a multivariate model with all of these metabolomic variables that can accurately predict the immunological recovery in HIV-patients with a low nadir CD4+ T-cell count after 36 months of ART.

Incomplete immunological recovery during ART is a relevant clinical problem; indeed, in our multicentre, prospective cohort study, 24% of the 64 treated HIV-infected patients who had viral suppression were considered INR using a restrictive definition (CD4+ T-cell count <250 cells/μl after 36 months of successful treatment). Several studies have tried to elucidate the impact of HIV-induced immunological changes on metabolism [15,16], and others focused on finding metabolomic differences between HIV-infected patients and healthy controls [17,18]. However, only a small number of studies have investigated baseline indicators of CD4+ T-cell recovery before ART. In those studies, older age, a lower nadir CD4+ T-cell count, higher immune activation, viral load and HCV coinfection have all been proposed as the most relevant predictive factors for a immunodiscordant response even though individually they were not able to predict treatment response, so their combined effect remains elusive [19,20]. The current study has included the variables of age and CD4+ T-cell count at baseline in the statistical analyses but none of them has presented a significant P value in the univariate comparisons (Table 1) nor showed importance of classification in the Random Forest model (Fig. 3). However, their inclusion in the logistic model slightly improved the AUC and the specificity in the ROC analysis (Fig. 4). Therefore, there is still the need to identify specific predictive factors for an early recognition and classification of immunological discordant individuals to propose the appropriate therapy to each situation.

Some studies have characterized the metabolomic profile of HIV/AIDS biofluids using metabolomic techniques such as proton NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry and demonstrated the ability to detect metabolites affected by infection and treatment [7]. However, none of them have been carried out using metabolism as the target for immunological recovery biomarker identification. For this reason, the current study could be considered novel research work aimed at identifying a useful metabolomic signature for the early prediction of immune response after ART in HIV-infected patients with a low nadir CD4+ T-cell count.

Most of the metabolomic findings obtained in the current study rely directly on the number of HDL particles. The role of HDL in immunity has been studied fairly extensively and several beneficial effects have been attributed to this lipoprotein class [21]. Notably, proteomics studies have revealed that HDL components exert regulatory functions on the immune system [21]. Accordingly, it has been accepted that HDL has an important role in host defence, contributing to both innate and adaptive immunity. As an example, apoliprotein A-I, the principal protein of HDL, impairs HIV fusion, thus preventing HIV cell penetration [22]. Moreover, this protein positively correlates with CD4+ T-cell count [23]. However, the most described function of HDL lipoproteins is its antiatherogenic role due to its ability to transport excess cellular cholesterol to the liver for excretion. In this sense, a number of studies have described the association between HIV infection and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [24,25]. Adverse lipid changes during infection could be a possible explanation for this association and, accordingly, the study of baseline lipoprotein profile could elucidate some points of this clinical situation. It has been elucidated that HDL-C and total HDL particles concentration, especially large HDL, are significantly lower among HIV-infected patients [23,26]. On the contrary, smaller LDL particles (the most atherogenic ones) are higher in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases such as HIV have the opposite behaviour higher [26,27]. All together contributes to an atherogenic profile among HIV patients and, consequently, to a higher risk for the development of CVD. Hence, all this previous findings are in accordance with our results since HDL particle concentration (especially the subclass ‘large’) and larger LDL sizes were increased further in the immunological responders metabolism at baseline; however, we also suggest a relationship between a lower atherogenic lipid profile and the prediction of immunological recovery in HIV-infected patients.

During inflammation and infection, serum triglycerides and VLDL levels increase, which in turn has an effect on other lipoproteins, such as an increase in the production of small, dense LDL and a decrease in the production of HDL [28]. This metabolomic mechanism completely agrees with our results, showing a positive correlation between the medium VLDL particles and the ratios of ‘total/HDL particles’ and ‘LDL/HDL particles’, high values of which are an indicator of nonrecovery. Moreover, a meaningful negative link between ‘LDL/HDL particles’ ratios and CD4+ T-cell recovery has already been reported in a previous study, in which total particles (including VLDL) were not measured [20]. Several beneficial immunological effects of HDL particles as well as damaging effects of LDL and VLDL particles have already been reported. However, no predictive role has been attributed to them so far.

Glucose metabolism plays a fundamental role in supporting the growth, proliferation and effector functions of T cells [29,30]. Several studies have demonstrated that HIV-infected patients have an increased glycolytic metabolism in CD4+ T-cells because activated immune cells consume glucose at an extremely high rate. Consequently, high plasma levels of this metabolite are associated with a low CD4+ T-cell count [31,32]. Therefore, glucose could be a confounder to immunological recovery due to its correlation with CD4+ T-cell count.

In summary, our experimental data establishes that HIV-infected patients with a baseline metabolomic pattern characterized by high levels of HDL particles (especially the subclass ‘large’), including HDL cholesterol and larger sizes of LDL particles, will have a better immunological recovery after treatment. On the other hand, patients with high ratios of non-HDL lipoprotein particles, high levels of VLDL particles (especially the subclass ‘medium’) and high concentrations of glucose will not fully recover CD4+ T-cells.

The study has limitations. Some of them come from the NMR technique itself. On one hand, the quantification of LMWMs is very challenging in nonfiltered plasma samples because of its high content of lipids and proteins. Even with the CPMG filter, residual signals of such high molecular weight molecules keep disturbing the identification and quantification of LMWMs. Moreover, due to the electronic filter applied to the CPMG samples, its quantification cannot be directly converted to absolute units, remaining quantified with arbitrary units. So, ultrafiltration of samples should be taken into account to enlarge and improve the profiling of LMWMs in further studies. The final list of 11 metabolites was the result of selecting only those metabolites which signals were ‘clean’ enough to be quantifiable in a reliable way. On the other hand, wrong spectral acquisitions produced by alterations in the magnetic field and bad water suppressions reduced the number of available samples to perform the study. Actually, the main limitation is the small sample size of our study population, especially due to the high restrictive inclusion criteria that we used. Therefore, the statistical power for establishing a predictive metabolomic pattern of immunological recovery was limited and also it could be other aspects that might affect immunological response to ART that were not assessed in this study. For this reason, further studies with larger cohorts are needed to confirm the strength of the proposed metabolomic signature as a possible diagnostic panel for immunological recovery prediction.

In conclusion, we have identified an association between the baseline metabolomic signature of HIV-infected patients with low nadir and their immunological response after ART treatment. This metabolomic signature, among other factors, could help to elucidate the underlying mechanistic pathways responsible for antiretroviral treatment response. Accordingly, this study provides new insights into HIV pathogenesis and suggests new clues for the development of novel diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic strategies for HIV.

Acknowledgements

F.V. and P.D. designed the study and provided direction to the study development and conduct. J.P., C.V., M.L.-D., S.V., M.L. and P.D. enrolled patients from the participating hospitals and provided the clinical information. X.V. and N.C. established the metabolomic methodology and J.G., R.M. participated in the acquisition of metabolomic data. E.R.-G., J.G., Y.M.P., R.B.-D., A.R. participated in the statistical analysis and the interpretation of data. V.A. provided technical and material support. E.R.-G., J.G. and Y.M.P. jointly wrote the initial article draft. J.B., N.C., M.L., X.V., P.D. and F.V. participated in critical revisions for intellectual content. All authors provided input into the report and approved the final version to be submitted for publication. The constructive comments and criticisms of the three reviewers helped us to improve the article and are greatly appreciated.

The current work was supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigacion Sanitaria (PI10/02635, PI13/00796, PI13/01912, PI14/01693, PI14/0700, PI14/0063 and PI16/00503) Instituto de Salud Carlos III; Fondos Europeos para el Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); Programa de Suport als Grups de Recerca AGAUR (2014SGR250 and 2009SGR1061); the Gilead Fellowship Program (GLD13/00168 and GLD14/293); the Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Economía, Innovación, Ciencia y Empleo (Proyecto de Investigación de Excelencia; CTS2593); the Red de Investigación en Sida (RIS) (RD12/0017/0002, RD12/0017/0005, RD12/0017/0014, RD12/0017/0029 and RD16/0025/0006) Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain. F.V. and P.D. are supported by a grant from the Programa de Intensificación de Investigadores, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (INT11/240, INT12/282 and INT12/383, INT13/232, INT15/226 and INT15/140). Y.M.P. was supported by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria through the ‘Miguel Servet’ program (CPII13/00037) and by the Consejería de Salud y Bienestar Social of Junta de Andalucía through the ‘Nicolás Monardes’ program (C-0010/13). A.R. is supported by a grant from the Acció Instrumental d’Incorporació de Científics i Tecnòlegs (PERIS SLT002/16/00101), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya. We want to particularly acknowledge the patients enrolled in this study for their participation and the BioBanc IISPV (B.0000853 + B.0000854) integrated in the Spanish National Biobanks Platform (PT13/0010/0029 & PT13/0010/0062) for its collaboration.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Esther Rodríguez-Gallego, Josep Gómez and Yolanda M. Pacheco contributed equally to the article.

Pere Domingo and Francesc Vidal are joint senior authors on the article.

References

- 1.Battegay M, Nüesch R, Hirschel B, Kaufmann GR. Immunological recovery and antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2006; 6:280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbeau P, Reynes J. Immune reconstitution under antiretroviral therapy: the new challenge in HIV-1 infection. Blood 2011; 117:5582–5590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pacheco YM, Jarrin I, Rosado I, Campins AA, Berenguer J, Iribarren JA, et al. Increased risk of non-AIDS-related events in HIV subjects with persistent low CD4 counts despite cART in the CoRIS cohort. Antiviral Res 2015; 117:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pacheco YM, Jarrín I, Del Amo J, Moreno S, Iribarren JA, Viciana P, et al. Risk factors, CD4 long-term evolution and mortality of HIV-infected patients who persistently maintain low CD4 counts, despite virological response to HAART. Curr HIV Res 2009; 7:612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massanella M, Negredo E, Clotet B, Blanco J. Immunodiscordant responses to HAART – mechanisms and consequences. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2013; 9:1135–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engsig FN, Zangerle R, Katsarou O, Dabis F, Reiss P, Gill J, et al. Long-term mortality in HIV-positive individuals virally suppressed for >3 years with incomplete CD4 recovery. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:1312–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sitole LJ, Williams AA, Meyer D. Metabonomic analysis of HIV-infected biofluids. Mol Biosyst 2013; 9:18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghannoum MA, Mukherjee PK, Jurevic RJ, Retuerto M, Brown RE, Sikaroodi M, et al. Metabolomics reveals differential levels of oral metabolites in HIV-infected patients: toward novel diagnostic targets. OMICS 2013; 17:5–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knobel H, Escobar I, Polo R, Ortega L, Teresa Martín-Conde M, Luis Casado J, et al. Recomendaciones GESIDA/SEFH/PNS para mejorar la adherencia al tratamiento antirretroviral en el año 2004. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2005; 23:221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mallol R, Amigó N, Rodríguez MA, Heras M, Vinaixa M, Plana N, et al. Liposcale: a novel advanced lipoprotein test based on 2D diffusion-ordered 1H NMR spectroscopy. J Lipid Res 2015; 56:737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gómez J, Brezmes J, Mallol R, Rodríguez MA, Vinaixa M, Salek RM, et al. Dolphin: a tool for automatic targeted metabolite profiling using 1D and 2D (1)H-NMR data. Anal Bioanal Chem 2014; 406:7967–7976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gómez J, Vinaixa M, Rodríguez MA, Salek RM, Correig X, Cañellas N. 9th International Conference on Practical Applications of Computational Biology and Bioinformatics. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otvos JD, Shalaurova I, Wolak-Dinsmore J, Connelly MA, Mackey RH, Stein JH, Tracy RP. GlycA: a composite nuclear magnetic resonance biomarker of systemic inflammation. Clin Chem 2015; 61:714–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereyra F, Jia X, McLaren PJ, Telenti A, de Bakker PIW, Walker BD, et al. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science 2010; 330:1551–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanley TL, Grinspoon SK. Body composition and metabolic changes in HIV-infected patients. J Infect Dis 2012; 205 Suppl:S383–S390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergersen BM, Schumacher A, Sandvik L, Bruun JN, Birkeland K. Important differences in components of the metabolic syndrome between HIV-patients with and without highly active antiretroviral therapy and healthy controls. Scand J Infect Dis 2006; 38:682–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadigan C, Meigs JB, Corcoran C, Rietschel P, Piecuch S, Basgoz N, et al. Metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular disease risk factors in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and lipodystrophy. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32:130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mondy K, Overton ET, Grubb J, Tong S, Seyfried W, Powderly W, Yarasheski K. Metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients from an urban, Midwestern US outpatient population. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:726–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore DM, Harris R, Lima V, Hogg B, May M, Yip B, et al. Effect of baseline CD4 cell counts on the clinical significance of short-term immunologic response to antiretroviral therapy in individuals with virologic suppression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 52:357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azzoni L, Foulkes AS, Firnhaber C, Yin X, Crowther NJ, Glencross D, et al. Metabolic and anthropometric parameters contribute to ART-mediated CD4+ T cell recovery in HIV-1-infected individuals: an observational study. J Int AIDS Soc 2011; 14:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu B, Wang S, Peng D, Zhao S. HDL and immunomodulation: an emerging role of HDL against atherosclerosis. Immunol Cell Biol 2010; 88:285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srinivas RV, Birkedal B, Owens RJ, Anantharamaiah GM, Segrest JP, Compans RW. Antiviral effects of apolipoprotein A-I and its synthetic amphipathic peptide analogs. Virology 1990; 176:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rose H, Hoy J, Woolley I, Tchoua U, Bukrinsky M, Dart A, et al. HIV infection and high density lipoprotein metabolism. Atherosclerosis 2008; 199:79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durand M, Chartrand-Lefebvre C, Baril J-G, Trottier S, Trottier B, Harris M, et al. The Canadian HIV and aging cohort study – determinants of increased risk of cardio-vascular diseases in HIV-infected individuals: rationale and study protocol. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17:611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dysangco A, Liu Z, Stein JH, Dubé MP, Gupta SK. HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, and measures of endothelial function, inflammation, metabolism, and oxidative stress. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0183511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kontush A. HDL particle number and size as predictors of cardiovascular disease. Front Pharmacol 2015; 6:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duprez DA, Kuller LH, Tracy R, Otvos J, Cooper DA, Hoy J, et al. Lipoprotein particle subclasses, cardiovascular disease and HIV infection. Atherosclerosis 2009; 207:524–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. De Groot LJ, Beck-Peccoz P, Chrousos G, et al. The effect of inflammation and infection on lipids and lipoproteins. MDText.com, Inc, Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer CS, Ostrowski M, Balderson B, Christian N, Crowe SM. Glucose metabolism regulates T cell activation, differentiation, and functions. Front Immunol 2015; 6:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newsholme EA, Crabtree B, Ardawi MS. The role of high rates of glycolysis and glutamine utilization in rapidly dividing cells. Biosci Rep 1985; 5:393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer CS, Ostrowski M, Gouillou M, Tsai L, Yu D, Zhou J, et al. Increased glucose metabolic activity is associated with CD4+ T-cell activation and depletion during chronic HIV infection. AIDS 2014; 28:297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKnight TR, Yoshihara HAI, Sitole LJ, Martin JN, Steffens F, Meyer D. A combined chemometric and quantitative NMR analysis of HIV/AIDS serum discloses metabolic alterations associated with disease status. Mol Biosyst 2014; 10:2889–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.