Abstract

Objective:

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers in women and has more severe mental and emotional effects than other types. Depression as a mental disorder affects people’s mental well-being, physical symptoms, occupational performance, and finally quality of life. The aim of this study was to determine depression levels in Iranian women with breast cancer.

Methods:

A systematic review study was conducted in 2017. English and Persian databases (PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science, Google Scholar, SID, Magiran) were searched with key words such as Depression Or Depressive Disorders AND Women AND Breast Cancer OR Tumor OR Neoplasm OR Malignancy AND Iran. Inclusion criteria allowed for cross-sectional studies conducted in Iran (published in English or Persian language journals), studies that had key words in their keywords or their titles and standard instruments for measuring depression in patients. Of the 160 publications found, eight were selected after reviewing the title, abstract and full article.

Results:

Age of women with breast cancer in selected studies ranged from 43.8 (SD = 47.1) to 55.9 (SD = 14.6) years. Duration of cancer in most studies was about 1-2 years. In most studies, mild levels of depression for women with breast cancer were present. However, in one study it was stated that 69.4% of participants had serious levels of depression.

Conclusions:

There is increase in the risk of depression in women with breast cancer. Therefore, it seems necessary to plan preventive and therapeutic measures in order to improve the mental health and quality of life of the affected patients.

Keywords: Depression, women, breast cancer, mental health, Iran

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers in women that have more severe mental and emotional effects than other types of cancers (Ramezani, 2001; Saniah and Zainal, 2010; Sharif Nia et al., 2017). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), breast cancer accounts for about 30% of all cancers among women (Bener et al., 2017). Also, the total number of breast cancer patients in Iran is about 40,000, and more than 7,000 patients are added each year (Shobiri et al., 2016).

Diagnosis of breast cancer is an extremely unpleasant and unbelievable experience for each person that can disrupt family life (Vedat et al., 2001). Meanwhile, fears and worries about the death and recurrence of the disease, mental impairment, financial concerns and family problems lead to the emergence and increase of severity of psychiatric disorders such as depression (Kai-na et al., 2011; Shakeri et al., 2015; Dowlatabadi et al., 2016). Eventually, depression as a mental disorder affects the thoughts, physical symptoms, occupational performance, and finally the quality of life of patients (Goudarzian et al., 2017; Hosseinzadeh-Khezri et al., 2014; Motamedi et al., 2015). Nowadays, medical diagnostic and therapeutic advances have led to an increase in the number of survivors of breast cancer thus, much attention has to be paid to the quality of life and cognitive function of affected individuals (Montazeri et al., 2001; Shakeri et al., 2015). Therapeutic interventions cause severe physical changes in these patients which have long-term adverse effects on their mental health. In this regard, the identification, diagnosis and treatment of depression not only affects the quality of life of individuals, but also affects their survival rate and increases their ability to cope with diseases (Didehdar Ardebil et al., 2013; Zainal et al., 2013).

So far, many studies have been conducted to investigate the prevalence of depression in women with breast cancer, which varies in different communities (Lueboonthavatchai, 2007; Manning and Bettencourt, 2011; Derakhshanfar et al., 2013; Bener et al., 2017). The findings of a study in Iran showed that 42.3% of patients with breast cancer suffer from moderate to severe depression (Shakeri et al., 2009). A systematic review study carried out by assessing 32 studies up to 2012 revealed that patients with breast cancer are at risk of depression (Zainal et al., 2013). Another systematic review study also reported that depression (majorly) is frequent among patients with breast cancer and thus create increasing functional impairment and poor treatment adherence (Fann et al., 2008).

With an overview of the available databases, we can say that a systematic review to assess depression in women with breast cancer has not yet been conducted in Iran. But Considering that breast cancer rates and its psychological problems such as depression in Iran are increasing (Shakeri et al., 2009; Watts et al., 2015), it necessary to conduct comprehensive and systematic studies to assess the levels of depression in Iranian women with breast cancer. Therefore, the current research was conducted as a systematic review with the aim of evaluating and summarizing articles that examined depression in Iranian women with breast cancer in order to provide conditions for planning preventive and therapeutic interventions in the future.

Materials and Methods

The present study is a systematic review conducted in 2017. It adhered to the preferred reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Panic et al., 2013) based on the sample of articles on depression of breast cancer patients in Iran.

Search strategy

We undertook a systematic review of PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of science, Google Scholar, SID, The Grey Literature Report, Civilica (for grey literature of abstract of congresses and conferences), Magiran, and Barakat Knowledge Network System databases of studies published between January 1, 1980 to August 1, 2017, with the search Mesh terms “Breast Neoplasms”, “Cancer”, “Tumor”, “Malignancy”, “Women”, “Iran”, “Depression”, “Depressive disorders” [with the use of operators OR and AND].

Selection of studies

Studies were reviewed for eligibility by two independent reviewers; disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer. When multiple articles were published on the same study, relevant outcomes were extracted from the articles as necessary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

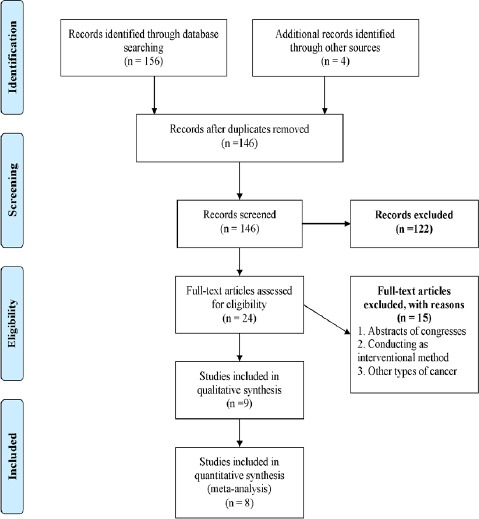

Studies had to meet all five of the following criteria for inclusion: Persian and English language articles, enrolled patients who presented with symptoms of depression; used original assessment tool for depression of patients; and conducted as cross-sectional; keywords should be mentioned in the title or the abstract section. We excluded studies that did not report the number of patients with breast cancer and their mean age. We also excluded reports that did not have English or Persian full texts. Diagram 1 shows the stages of selecting the articles based on PRISMA guidelines.

Diagram 1.

Inclusion Stages of Studies

As shown in Diagram 1, 160 articles were collected by searching the mentioned databases after excluding (with some reasons including and not relative to the aim of this study [n = 87], non-Iranian systematic review studies [n = 16] and did not have English or Persian full texts [n = 20]). After that, selected articles were carefully assessed and 8 articles remained.

Quality assessment

The remaining articles were entered into the quality assessment stage. Quality was assessed independently by two authors using The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. This scale was used for assessing the quality of observational studies (Stang, 2010). This scale uses a “star” system (with maximum of nine stars) to assess the quality of a study in three domains: selection of participants; comparability of study groups; and the ascertainment of interest outcomes. Studies that received a score of nine stars were judged to be of high quality; while those that scored seven or eight stars were considered of medium quality. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and, when necessary, by consulting a third review author. Finally, moderate and high quality studies remained in this study.

Data extraction

Then the following information was extracted for each study when provided: first author, year of publication, study design, depression assessment tool, mean age of participants, number of cases tested, results, and duration of cancer. Validity of selected checklist was confirmed by 10 experts of associate university of medical sciences after significant revisions.

Results

Primary characterizes of studies

The obtained studies were conducted from 2001 to 2016 with the aim of determining depression in Iranian women with breast cancer. The age of women with breast cancer in selected studies ranged from 43.81 (SD = 47.12) to 55.91 (SD = 14.55) years. Also, minimum and maximum sample sizes were 60 and 297, respectively. Duration of cancer in most studies was about 1-2 years.

Depression assessments

Depression in Iranian women with breast cancer was assessed by Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (4 studies) (Ramezani, 2001; Derakhshanfar et al., 2013; Didehdar Ardebil et al., 2013; Shakeri et al., 2015), Zung depression scale (1 study) (Shakeri et al., 2009), Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90R) (1 study) (Hadi et al., 2009), and Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) (2 studies) (Musarezaie et al., 2014; Mehrabani et al., 2016). Based on the items expressed in Table 1, in most of the studies, the minimum levels of depression for women with breast cancer were presented. However, in one study it was stated that 69.4% of participants had serious levels of depression. Other findings are provided in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies (N=8)

| Author (year) | Study design | Sample size (n) | Mean age of Participants | Instruments | Duration of cancer | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derakhshanfar et al., (2013) | Cross-sectional | 111 Women with breast cancer who were undergoing treatments or follow up during 15 months | 47.05±11.68 years | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) - 21 | 52.3%:1 year or less than 1 year 31.5%:1 to 2 years 16.2%: More than 2 year |

Mild Depression: 33.8% Moderate Depression: 38.2% Severe Depression: 23.5% Very severe Depression:4.5% |

| Shakeri et al., (2009) | Descriptive | 78 Women with breast cancer who referred to chemotherapy centers | 45.15 years | Zung depression scale-20 | 21.8%:Less than 6 months 15.9%:6-9 months 26.9%:9-12 months 20.5%:More than 15 months |

Mild Depression: 57.7% Moderate Depression: 26.9% Severe Depression: 15.3% |

| Ramezani, (2001) | Descriptive | 120 Women with breast cancer who referred to chemotherapy centers | 47.53 years | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)- 21 | 33.3%:13-24 months 13.3%:25-36 months |

Normal : 32.5% Moderate Depression:30.8% Severe Depression:10% |

| Hadi et al., (2009) | Cross-sectional | 178 patients with breast cancer stage I-III with three to eighty months of follow up and 400 other women randomly selected from the general population | 48.6±9.16 years (breast cancer patients) 45.4+7.12 (Normal controls) |

Symptom Checklist- 90 Revised (SCL-90R)-90 | 88.7% of patients: 1 to 5 years, 4.5%:Less than 1 year 6.8%:More than 5 years |

Depression (Breast cancer patients): Mean+SD= 1.03±0.78 Depression (Normal controls): Mean+SD= 1.03±0.68 P value: 0.970 |

| Didehdar Ardebil et al., (2013) | Cross-sectional | 60 Iranian women aged 18 years or more undergoing curative treatment through chemotherapy or radiotherapy | 43.81±47.12 years | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)- 21 items | Mean ± SD= 3.64±3.98 | Symptoms of mild-to-severe depression : 50% of patients |

| Shakeri et al., (2016) | Descriptive | 98 women with breast cancer who referred to oncology center | 47.60±14.05 years | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)- 21 | Not presented. | No depression:4.1% Low depression:8.1% Moderate depression: 18.4% Serious depression: 69.4% |

| Musarezaie et al., (2013) | Descriptive-analytic | 297 hospitalized patients with breast cancer | Not presented. | Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS)- 42 | Mean ± SD= 39.5±8.43 months | Low Depression: 32.8% Moderate Depression: 33.6% High Depression: 16.5% Severe Depression: 17.1% |

| Mehrabani et al., (2016) | Descriptive-analytic | 260 patients with breast cancer who referred to hospital | 55.91+14.55 years | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS)- 42 | Mean ± SD= 21±8.48 months | Normal: 48.8% Mild Depression: 13.1% Moderate Depression: 10.7% Severe Depression: 11.9% Very severe Depression: 15.50% |

Discussion

Cancer, especially breast cancer among women, can be one of the important causes of depression in patients. The present study was conducted to determine the levels of depression in Iranian women with breast cancer in a systematic review. According to the findings, of the most studies conducted so far, mild levels of depression have been reported in women with breast cancer, but one study reported that 69.4% of the patients suffered from severe levels of depression (Shakeri et al., 2015). Of a fact, the prevalence of depression has been different in other communities, such that in Asian countries such as China and Thailand, 26% (Chen et al., 2010) and 16.7% (Lueboonthavatchai, 2007) respectively, have been reported. The results of another study in India indicated that 21.5% of patients with breast cancer are depressed (Purkayastha et al., 2017). In Turkey, 27.7% of women with breast cancer experienced moderate depression and 19.5% of them had severe depression (Bener et al., 2017). Also, in studies conducted in the United States during the years 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2012, the prevalence of depression in patients with breast cancer have been reported as 26% (Broeckel et al., 2000), 10% (Speer et al., 2005), 42% (Christie et al., 2010), and 56% (Begovic-Juhant et al., 2012), respectively. In European countries such as Germany, it was reported that 11% of breast cancer patients suffered from moderate depression and 12% of them suffered from high levels of depression (Mehnert and Koch, 2008). A study in Greece also suggested that 54.4% of women with diagnosis of breast cancer experienced depression (Fradelos et al., 2017). Also, a study conducted in Italy reported that 18% of patients with breast cancer were depressed (Pumo et al., 2012). The possible causes of the difference in these studies are the difference in demographic variables such as age, marital status, duration of cancer, type of treatment and number of treatment sessions (Rajabizadeh et al., 2005), as well as locational and cultural diversity that can affect the mental and psychological conditions of patients. On the one hand, in justifying the differences in the results of these studies, the type of instruments used and the way in which the scores obtained from these instruments for assessing depression in participants in studies were interpreted should not be ignored.

It also seems that what can lead people with breast cancer into psychological disorders such as depression are factors such as prolonged treatment, frequent admission and side effects of radiation therapy and chemotherapy (Burgess et al., 2005; Bener et al., 2017; Bhattacharyya et al., 2017). The breast is one of the symbols of femininity and the idea of losing this organ is painful and intolerable to women (Ahmad Nejhad et al., 2014). The diagnosis of breast cancer may include reactions such as fear of mastectomy and lack of attractiveness (Moreira and Canavarro, 2010), disorder in women’s identity (Shayan et al., 2016), physical impairment (Khademi and Sajadi Hezaveh, 2009), and mental health disorder (Pedram et al., 2011). Cancer can also exacerbate feelings of reduced ability to function, lack of competence, and lower self-esteem in affected people, and eventually lead to depression (Goudarzian et al., 2017).

Hypotheses on the relationship between depression and breast cancer

Various hypotheses have been presented on the relationship between depression and breast cancer. The first hypothesis considered depression as a risk factor for breast cancer. In this regard, various studies have provided valuable results. In a review study, McKenna et al. and Duijts et al. suggested that depression and mood disorders could increase the risk of breast cancer (McKenna et al., 1999; Duijts et al., 2003). Among the population of patients with breast cancer, a variety of factors such as culture and ethnicity, low income, pain and quality of life associated with health can be associated with depression. The above-mentioned factors and the onset of depression can reduce the willingness of individuals to take screening counseling for early diagnosis of breast cancer. In fact, it seems that people with depression are less likely to think about their health and neglect screening tests for early diagnosis, treatment and better prognosis (Ell et al., 2005).

Considering depression as the predictor of mortality rate due to breast cancer is the second most relevant hypothesis. For this hypothesis, researchers believe that depression can be a major contributor to cancer progression. First, depression significantly reduces motivation and compatibility with treatments such as chemotherapy (Ayres et al., 1994). Secondly, major depression could be an important predictor of late-stage breast cancer diagnosis because patients confronted with a lump will delay seeking medical consultation (Desai et al., 1999).

Therefore, considering the above two factors, depression can be a harmful factor in the outcomes of these patients (Reich et al., 2008). Some researchers are also advocating for depression as a protective and preventive agent of breast cancer (as a third hypothesis). So far, two retrospective studies have suggested that women with depression have a lower risk of developing breast cancer (Nyklíček et al., 2003; Aro et al., 2005). However, there is still insufficient evidence to confirm the validity of this hypothesis, as further studies are needed.

In the latest hypothesis, that is, assessing the link between depression and breast cancer, breast cancer is also identified as a causative agent of depression. It is almost possible to state that all the articles entered into this review study supported this hypothesis. During treatment, patients become more likely to develop depression as a result of changes in their quality of life (Mitchell et al., 2014; Fallowfield and Jenkins, 2015), body condition (such as mastectomy) and various physical symptoms. According to the results (of the entered studies to this study), the presence of depression prior to the onset of breast cancer is unknown. However, depression screening for these patients is recommended.

Strengths and limitations

This review has a number of strengths. We searched for articles systematically and included studies using clearly defined criteria to minimize selection bias. We also judged studies’ methodological quality and excluded those that had specific design flaws rather than merely assign quality scores.

This study, as many others have serious limitations. First, despite the high prevalence of breast cancer in Iranian women, very limited studies have been published. The second limitation was the lack of meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of the existing studies. Thirdly, our assessments of studies, both for relevance and quality, were based on information available in published reports. This may mean that we excluded studies that were well conducted but simply poorly reported. However, even if this were the case, it would be unlikely to explain much of the methodological shortcomings apparent in such reports. Finally, we did not attempt to include grey literature by contacting relevant experts for unpublished manuscripts. However, we did make substantial efforts to find all relevant published studies through inclusive search strategies.

Recommendations

It is recommended that more studies (with deep detailed and comprehensive sample) be undertaken for a better understanding of the risk of depression and its prevalence. Also, depression in Iranian samples from other part of the world have not yet been assessed; thus, it is recommended. It is therefore required that future systematic review studies be done with a tendency towards meta-analysis.

Implications

Depression is an important and potentially fatal but treatable complication of breast cancer. As well as having substantial effects on quality of life, depression contributes to non-adherence to medical treatments (DiMatteo and Haskard-Zolnierek, 2010). In order to plan effective services, we need accurate estimates of its prevalence in clinically meaningful groups of breast cancer patients. Despite a large number of relevant publications, it was striking that few studies met our basic quality criteria and we, therefore, currently lack adequately precise and useful data on the prevalence of depression in clinically relevant groups of breast cancer patients. Finally, we wish to make a plea for an improvement in the quality of research published in this area and suggest that the quality criteria used in this review, along with the use of expert interviewers, are a prerequisite for the funding and publication of future studies on this topic.

The results of studies have shown that breast cancer can increase the risk of depression in women with breast cancer. Also, the results of this study can be helpful in future studies to prevent and treat psychiatric disorders such as depression in order to promote mental health and quality of life in affected patients.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Research deputy of Mazandaran University of medical sciences (Sari, Iran) with Grant No: 124 approved in 2017.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad Nejhad R, Farid Hoseini F, Asadi M. Comparing the psychological effect of breast conserving surgery with modified radical mastectomy on women having breast cancer in Mashhad university of medical sciences. Med J Mashhad Uni Med Sci. 2014;57:770–5. [Google Scholar]

- Aro AR, De Koning HJ, Schreck M, et al. Psychological risk factors of incidence of breast cancer:a prospective cohort study in Finland. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1515–21. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres A, Hoon PW, Franzoni JB, et al. Influence of mood and adjustment to cancer on compliance with chemotherapy among breast cancer patients. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:393–402. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begovic-Juhant A, Chmielewski A, Iwuagwu S, et al. Impact of body image on depression and quality of life among women with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:446–60. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.684856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bener A, Alsulaiman R, Doodson L, et al. Depression, hopelessness and social support among breast cancer patients:in highly endogamous population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:1889–96. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.7.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S, Bhattacherjee S, Mandal T, et al. Depression in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in a tertiary care hospital of North Bengal, India. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61:14–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.200252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeckel JA, Jacobsen PB, Balducci L, et al. Quality of life after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;62:141–50. doi: 10.1023/a:1006401914682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, et al. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer:five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Lu W, Zheng Y, et al. Exercise, tea consumption, and depression among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:991–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie KM, Meyerowitz BE, Maly RC. Depression and sexual adjustment following breast cancer in low-income hispanic and non-hispanic white women. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1069–77. doi: 10.1002/pon.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derakhshanfar A, Niayesh A, Abbasi M, et al. Frequency of depression in breast cancer patients:A study in farshchian and bresat hospitals of Hamedan during 2007-8. Iran J Surg. 2013;21:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Desai MM, Bruce ML, Kasl SV. The effects of major depression and phobia on stage at diagnosis of breast cancer. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1999;29:29–45. doi: 10.2190/0C63-U15V-5NUR-TVXE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didehdar Ardebil M, Bouzari Z, Hagh Shenas M, et al. Depression and health related quality of life in breast cancer patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63:45–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR, Haskard-Zolnierek KB. In 'depression and cancer'. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2010. Impact of depression on treatment adherence and survival from cancer; pp. 101–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dowlatabadi MM, Ahmadi SM, Sorbi MH, et al. The effectiveness of group positive psychotherapy on depression and happiness in breast cancer patients:A randomized controlled trial. Electron Physician. 2016;8:2175–80. doi: 10.19082/2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duijts SF, Zeegers M, Borne BV. The association between stressful life events and breast cancer risk:a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:1023–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Sanchez K, Vourlekis B, et al. Depression, correlates of depression, and receipt of depression care among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3052–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Psychosocial/survivorship issues in breast cancer:are we doing better? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:335. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fann JR, Thomas-Rich AM, Katon WJ, et al. Major depression after breast cancer:a review of epidemiology and treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:112–26. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fradelos EC, Papathanasiou IV, Veneti A, et al. Psychological distress and resilience in women diagnosed with breast cancer in Greece. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:2545–50. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.9.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzian AH, Bagheri Nesami M, Zamani F, Nasiri A, Beik S. Relationship between depression and self-care in Iranian patients with cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:101–6. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzian AH, Jafari A, Bagheri Nesami M, et al. Understanding the link between depression and pain perception in Iranian cancer patients. World Cancer Res J. 2017;4:e880. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi N, Reza A, Talei AR. Anxiety, depression and anger in breast cancer patients compared with the general population in Shiraz, Southern Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2009;2009:312–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinzadeh-Khezri R, Rahbarian M, Sarichloo ME, et al. Evaluation effect of logotherapy group on mental health and hope to life of patients with colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy. Bulletin of Environment. Pharmacol Life Sci. 2014;3:164–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kai-na ZH, Xiao-mei L, Hong Y, et al. Effects of music therapy on depression and duration of hospital stay of breast cancer patients after radical mastectomy. Chin Med J. 2011;124:2321–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademi M, Sajadi Hezaveh M. Breast cancer:A phenomenological study. J Arak Univ Med Sci. 2009;12:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lueboonthavatchai P. Prevalence and psychosocial factors of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:2164–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Bettencourt BA. Depression and medication adherence among breast cancer survivors:bridging the gap with the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1173–87. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.542815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna MC, Zevon MA, Corn B, et al. Psychosocial factors and the development of breast cancer:a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 1999;18:520–31. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehnert A, Koch U. Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:383–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabani F, Barati F, Ramezanzade Tabriz E, et al. Unpleasant emotions (stress, anxiety and depression) and it is relationship with parental bonding and disease and demographic characteristics in patients with breast cancer. Iran J Breast Dis. 2016;9:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Santo Pereira IE, Yadegarfar M, et al. Breast cancer screening in women with mental illness:comparative meta-analysis of mammography uptake. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:428–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri A, Jarvandi S, Haghighat S, et al. Anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients before and after participation in a cancer support group. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45:195–8. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira H, Canavarro MC. A longitudinal study about the body image and psychosocial adjustment of breast cancer patients during the course of the disease. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:263–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motamedi A, Haghighat S, Khalili N, et al. The Correlation between treatment of depression and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Iran J Breast Dis. 2015;8:42–8. [Google Scholar]

- Musarezaie A, Naji Esfahani H, Momeni Ghaleghasemi T, et al. The relationship between spiritual wellbeing and stress, anxiety, and depression in patients with breast cancer. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2014;30:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nyklíček I, Louwman W, Van Nierop P, et al. Depression and the lower risk for breast cancer development in middle-aged women:a prospective study. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1111–7. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panic N, Leoncini E, De Belvis G, et al. Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedram M, Mohammadi M, Naziri G, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral group therapy on the treatment of anxiety and depression disorders and on raising hope in women with breast cancer. Social Women. 2011;1:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pumo V, Milone G, Iacono M, et al. Psychological and sexual disorders in long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer Manag Res. 2012;4:61–5. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S28547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purkayastha D, Venkateswaran C, Nayar K, et al. Prevalence of depression in breast cancer patients and its association with their quality of life:A cross-sectional observational study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:268–73. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_6_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajabizadeh G, Mansoori SM, Shakibi MR, et al. Determination of factors related to depression in cancer patients of the oncology ward in Kerman. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2005;12:142–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ramezani T. Degree of depression and the need for counseling among women with breast cancer in Kerman chemotherapeutic centers. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2001;6:70–8. [Google Scholar]

- Reich M, Lesur A, Perdrizet-Chevallier C. Depression, quality of life and breast cancer:a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110:9–17. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saniah AR, Zainal NZ. Anxiety, depression and coping strategies in breast cancer patients on chemotherapy. MJP Online Early. 2010;19:22–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shakeri J, Abdoli N, Payandeh M, et al. Frequency of depression in patients with breast cancer referring to chemotherapy centers of Kermanshah educational centers. (2007-2008) J Med Counc I R Iran. 2009;27:324–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shakeri J, Golshani S, Jalilian E, et al. Studying the amount of depression and its role in predicting the quality of life of women with breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;17:643–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.2.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif Nia H, Pahlevan Sharif S, Lehto RH, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of a Persian version of the death depression scale-revised:a cross-cultural adaptation for patients with advanced cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47:713–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayan A, Khalili A, Rahnavardi M, et al. The Relationship between sexual function and mental health of females with breast cancer. Sci J Hamadan Nurs Midwifery Fac. 2016;24:221–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shobiri E, Amiri M, Haghighat MJ, et al. The diagnostic value of impedance imaging system in patients with breast mass. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2016;19:427–35. [Google Scholar]

- Speer JJ, Hillenberg B, Sugrue DP, et al. Study of sexual functioning determinants in breast cancer survivors. Breast J. 2005;11:440–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedat I, Perinan G, Seref K, et al. The relationship between diease features and quality of life in patient with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24:490–5. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200112000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts S, Prescott P, Mason J, et al. Depression and anxiety in ovarian cancer:a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007618. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zainal NZ, Nik-Jaafar NR, Baharudin A, et al. Prevalence of depression in breast cancer survivors:a systematic review of observational studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:2649–56. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.4.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]