Abstract

Affirming one’s racial identity may help protect against the harmful effects of racial exclusion on substance use cognitions. This study examined whether racial versus self-affirmation (versus no affirmation) buffers against the effects of racial exclusion on substance use willingness and substance use word associations in Black young adults. It also examined anger as a potential mediator of these effects. After being included, or racially excluded by White peers, participants were assigned to a writing task: self-affirmation, racial-affirmation, or describing their sleep routine (neutral). Racial exclusion predicted greater perceived discrimination and anger. Excluded participants who engaged in racial-affirmation reported reduced perceived discrimination, anger, and fewer substance use cognitions compared to the neutral writing group. This relation between racial-affirmation and lower substance use willingness was mediated by reduced perceived discrimination and anger. Findings suggest racial-affirmation is protective against racial exclusion and, more generally, that ethnic based approaches to minority substance use prevention may have particular potential.

Keywords: self-affirmation, racial discrimination, racial-affirmation, substance use, exclusion

Substance use is directly or indirectly associated with all of the leading causes of death among Black young adults aged 18–30: homicide, accidents, suicide, cancer, heart disease, pregnancy complications, and HIV/AIDS (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017; Kochanek et al., 2016). Although Black adolescents tend to use substances less than White adolescents (Bachman et al., 2011), substance use rates tend to cross-over in young adulthood, and substance use problems become more prevalent, proportionally, among young Black adults than young White adults (French, et al., 2002). This “racial cross-over” effect (Kandel, et al., 2011) has been demonstrated with both marijuana use (Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Keyes et al., 2015) and a higher likelihood of alcohol-related problems for Blacks who drink (Witbrodt, et al., 2014). In addition, among Blacks aged 18–25, alcohol and marijuana use rates peak (Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Finlay et al., 2012) and they are significantly more likely to need substance use treatment (Lipari & Hager, 2013) compared to other ages. Racial discrimination (discrimination) is an important factor contributing to these health inequities (Gibbons & Stock, in press). In fact, several studies have found synchronous relations among Blacks between discrimination and reports of substance use (e.g., Borrell et al., 2007; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Gibbons and colleagues also found that discrimination predicted substance use 2 and 5 years later among Black adolescents and their parents in the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS; Gibbons, et al., 2004; Gibbons et al., 2007). This is especially disconcerting given that Blacks report experiencing more racial discrimination compared to other racial groups in the U.S. (Tropp et al., 2012) and that discrimination is associated with worse physical health (e.g., higher blood pressure) and mental health (e.g., greater distress; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams & Mohammed, 2009).

Fortunately, not all Black youth experience these negative effects on health and researchers have found several protective mechanisms that are relevant to these experiences. The primary mechanisms are all associated with social identity and experiences connected to race – including racial identity (Brondolo, et al., 2009; Jones & Neblett, 2016; Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umana-Taylor, 2012). Although researchers increasingly acknowledge the importance of including mechanisms associated with positive RI into preventions and interventions designed to reduce substance use (e.g., the Strong African American Families program [SAAF]; Brody et al., 2004; Gerrard et al., 2006), relatively little has been done to examine ways to reduce the negative effects of discrimination on the health of Black young adults.

An important way to understand and reduce the relation between discrimination and substance use is to examine the psychological and emotional factors that buffer (reduce) and mediate the relation. One promising buffer is racial affirmation, which includes affirming positive aspects of social (racial) identity or values (Stock, et al., 2011). Another potential application, which has been shown to reduce the negative effects of psychological threat on academic achievement among Black adolescents and reduce defensive responses to health-related information, is self-affirmation (Cohen et al., 2009; Sherman & Cohen, 2014). Self-affirmation includes affirming positives aspects of personal identity or values (Sherman & Cohen, 2014). The current study examined the potential buffering effects of both racial and self-affirmation on negative affect (a potential mediator of the effects) and substance use (alcohol and drug) cognitions in response to a recent experience of discrimination.

Examining the Effects of Discrimination on Substance Use Risk Cognitions in the Lab

One of the most common forms of discrimination faced by minorities is being excluded or ignored (Brondolo et al., 2011; Smart Richman & Leary, 2009). Racial exclusion results in negative affect (Smart Richman & Leary, 2009; Stock et al., 2015). A very effective way of manipulating exclusion in the lab is via Cyberball, an online ball-tossing game (Hartgerink, et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2000). During the game, participants are included or excluded by bogus players, who are part of the paradigm programmed by the researchers. The other “players” are represented by avatars, and photos can be used to manipulate player characteristics (e.g., race and gender). Studies using Cyberball to examine the causal effects of discrimination (via racial exclusion) have revealed that Blacks do attribute exclusion by Whites to racial discrimination and vice versa (Goodwin et al., 2010; Masten et al., 2011; Stock et al., 2011).

The studies that have examined substance use cognitions in response to racial exclusion and resulting perceptions of discrimination have used both explicit and indirect measures. The explicit measure have been guided by the prototype/willingness model (PWM; Gibbons et al., 2015; Stock et al., 2013). A central tenet of the model is that not all health behaviors are planned, especially when they involve health risk among adolescents and young adults (cf. Rivis et al., 2006). Instead, many risky behaviors are reactions to risk-conducive situations. These reactions are captured in a proximal antecedent to behavior, termed behavioral willingness. Willingness is influenced by contextual factors and affect, and predicts risk behaviors (see Todd et al., 2016 and van Lettow et al., 2016 for meta-analyses) often better than intentions for adolescents (Gibbons et al., 2015). Indirect measures of use cognitions have involved word associations (Thush et al., 2007), which also predict substance use behavior and capture cognitions not always identified with explicit methods (Krank et al., 2010; Rooke et al., 2008). Previous studies have shown that among Black young adults, racial exclusion, like discrimination, predicts negative affect, substance use willingness and word associations (Gerrard et al., 2012; Gibbons et al., 2012; Stock et al., 2013; Stock et al., 2017).

Racial Identity as a Protective Mechanism

One individual difference factor shown to moderate the impact of discrimination on health outcomes among African Americans is racial/ethnic identity (RI) (Brondolo et al., 2009; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). Generally, RI refers to an aspect of self-concept that derives from an individual’s knowledge of their ethnic or racial group membership and the significance, attitudes, and meaning they attach to that membership (Phinney, 1992; Sellers et al., 1998). Several studies have found that different forms of RI are protective against the negative effects of discrimination on health (Greene et al., 2006; Sellers et al., 2003; Stock et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2003). In addition, intervention programs with Black youth have begun to incorporate aspects of positive RI to promote psychosocial development (see Jones & Neblett, 2016). Although not all studies of RI have demonstrated protective effects with regard to substance use (Gray & Montgomery, 2012), higher levels of RI are usually associated with more negative attitudes toward substances and less substance use (Brody et al., 2006; Pugh & Bry, 2007; Stock et al., 2013). For example, among FACHS adolescents, RI was associated with less affiliation with substance users, and, in turn, lower drug use willingness and substance use 5 years later (Stock et al., 2013). This was particularly true among adolescents living in racially integrated environments. This relation was also examined in the lab, by asking a sample of these adolescents to imagine a racial discrimination experience at work. As expected, those with lower levels of RI reported the highest drug use willingness (Stock et al., 2011).

Reducing the Impact of Discrimination: Racial-Affirmation and Self-Affirmation

Experimental research is needed to help find effective coping strategies that victims of discrimination can use in the face of threat. One promising application that incorporates aspects of RI is racial-affirmation, which includes affirming positive aspects of one’s racial identity, values, and connections (Stock, et al., 2011). Racial-affirmations may have unique protective benefits above and beyond more personal identity or self-affirmations when faced with a racial threat. Racial-affirmation can help highlight positive group-identifications and feelings about one’s race, and feelings of connectedness (Stock et al., 2011). Focusing on in-group identity has implications for enhancing the well-being of minorities faced with discrimination (Branscombe et al., 1999). Social identity and social cure research has demonstrated the importance of social groups (including interventions designed to increase feelings of social identity) in helping people cope with being part of a devalued group or when faced with a social threat (including prejudice) (Haslam et al., 2009). Thus, when making ones’ RI salient, the focus shifts from a personal to a shared identity, which could be protective when face with a shared threat (e.g., racism).

In one recent study, we examined the protective effects of racial-affirmation by having Black participants write about what it means to them to be Black and their sense of connection to their racial group after being excluded or included by Whites in the Cyberball game (Stock et al., 2011). Those who were excluded attributed the exclusion to racial discrimination and reported more willingness to use substances. However, the relation between racial exclusion and willingness was not significant among participants who racially affirmed.

Another potential application is self-affirmation (Cohen et al., 2009). Self-affirmation includes affirming positives aspects of personal identity or values (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). Self-affirmation, in general, decreases negative reactions to psychological threats to the self (or one’s racial group) and protects self-worth by allowing individuals to maintain a positive self-concept (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). For example, self-affirmation reduced the negative effects of stereotype threat on the performance of females in physics and mathematics courses (Martens et al., 2006; Miyake et al., 2010). In addition, self-affirmation reduced the effects of stereotype threat on the academic achievement of Black and Latino students (Cohen et al., 2009; Sherman et al., 2013). Thus, self-affirmation may also reduce the negative effects of racial exclusion.

Discrimination, Affirmation, Anger, and Substance Use

Numerous studies have found heightened levels of anger/hostility and depression/sadness in response to social exclusion as well as racial exclusion/discrimination (Gibbons et al., 2010; 2014; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams, 2007). However, anger is even more likely (than sadness) when the exclusion is perceived to be unfair (Chow et al., 2008; Smart Richman & Leary, 2009)—as is likely to be the case when it is race-based. Feelings of anger are, in turn, associated with substance use (Aklin et al., 2009). This may be due, in part, to efforts at mood regulation and/or coping mechanisms–substance use can mute anger (Aklin et al., 2009; Wills & Stoolmiller, 2002). Moreover, longitudinal research with Black adolescents from FACHS found that anger/hostility, more so than depression/sadness, mediates the relation between discrimination and substance use (Gibbons et al., 2010; 2012). Experimental research using Cyberball has also demonstrated that racial exclusion and resulting perceptions of discrimination increase feelings of anger, which, in turn, are associated with use cognitions (Stock et al., 2011).

However, from a translational perspective, research that examines whether affective reactions mediate the effects of affirmation on use cognitions after an experience of discrimination (via racial exclusion) is needed. In general, findings on mood as a mediator of self-affirmation effects have been inconsistent (McQueen & Klein, 2006), and self-affirmations in studies with minorities have not been found to have an effect on general positive or negative affect (Burgess et al., 2014). Several researchers have called for studies that examine specific emotions after affirmations in response to different forms of stress/exclusion (Chow et al., 2008; Harris et al., 2013). There is evidence to suggest that among Black young adults, racial-affirmations protect against the negative effects of racial exclusion on anger (again, more so than sadness or anxiety; Stock et al., 2011), which, in turn, should reduce the effects on substance use cognitions. Yet, research has not examined anger in response to racial versus self-affirmation after experiencing a threat to one’s RI (i.e., racial discrimination via racial exclusion).

Overview

The design of our experimental study was a 2 (racial exclusion vs. racial inclusion) × 3 (self-affirmation vs. racial-affirmation vs. neutral writing) factorial. The current study was designed to examine whether racial- and/or self-affirmation (in comparison with a neutral writing task) can mitigate the anger and substance use cognitions resulting from racial exclusion. We also examined if racial-affirmation would be more protective for racial exclusion than self-affirmation among excluded participants. Given that racial exclusion involves a threat to one’s RI, we hypothesized that racial-affirmation, in particular, would be associated with reduced anger and substance use vulnerability among Blacks when excluded by Whites. Finally, we hypothesized that the affirmation writings would not have a significant effect among the included participants, who would not experience a threat (Cohen et al., 2009).

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through newspaper and online advertisements around the Washington, D.C. metro area. They were told the study concerned the relations among health, stress, personality, and the social environment. Three hundred sixty-four young adults who contacted the lab met the criteria for participation, which were: identifying as African American/Black with or without Hispanic ethnicity, and aged 18 through 25; 316 completed the pre-manipulation survey. Of the 316, 243 completed both the pre-manipulation survey and lab-based portions of the present study. Four participants were excluded because of high levels of verbal suspicion and three were excluded because they did not follow directions. Thus, the final sample consisted of 236 participants (119 females; M age = 22.26, SD = 2.22), of which 48% were currently enrolled in school (community colleges, online education, local universities).

Procedure

Following a screening call to ensure they qualified for the study, participants were sent a link to complete the pre-manipulation survey online via SurveyMonkey (2016). Basic demographic questions, personality and social experience measures (intended for a different study), and risk behaviors over the past six months were assessed. Between 2 and 4 weeks after completing the survey, participants came to the lab, where they were told they would first be playing a four-person online ball-tossing game with three other young adults. They were told the game was designed to examine the effects of mental visualization on task performance. Once the experimenters (blind to condition) introduced the study, participants were left alone. The ball-tossing game was a modified version of Cyberball. Participants were led to believe that the other “players” were three White same sex 18–25 year olds. This was done by showing them bogus photos of the players and telling them the other players could see their photo (Gerrard et al., 2012; Stock et al., 2011; 2013; 2017). They were randomly assigned to the exclusion or inclusion conditions. In the exclusion condition (n = 116), participants received the ball three times at the beginning of the game, and then were excluded for the rest of the game. In the inclusion condition (n = 121), participants received the ball 25% of the time. The game lasted approximately three minutes and there were 40 throws in total. Participants were then randomly assigned to the racial-affirmation (n = 81), self-affirmation (n = 77), or neutral writing condition (n = 79). Racial-affirmation participants were asked to “Think about the positive feelings you have associated with being African American. Write about a specific time that made you feel good about being African American and the positive emotions that you felt.” Self-affirmation participants were asked to “Think about the positive feelings you have associated with being you. Write about a specific time that made you feel good about yourself and the positive emotions that you felt.”1 Participants in the neutral condition were asked to write about their sleep habits. Two independent coders verified participants followed the writing directions. The writing task was followed by the word association task, anger, substance use willingness, and then perceived discrimination measures. Finally, participants were debriefed and paid $60 for their time.

Measures

Pre-manipulation control variables

Demographics

Participants reported their: gender (coded 0 = male, 1 = female), age, and student status (0 = not enrolled in school, 1 = currently enrolled in school).

Past substance use

Participants were asked how often they had: drunk alcohol and used marijuana, during the past six months (1 = never to 7 = 5–7 times/week).2

Post-manipulation measures

Manipulation checks

Participants were asked how much they were ignored and excluded during the game (2 items; 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely), which comprised the perceived exclusion manipulation check (r = .92, p < .001). To examine whether the Cyberball manipulation resulted in feelings of perceived discrimination, participants were asked: “To what extent do you feel you were being excluded based on your race?” and “To what extent do you feel you were being discriminated against based on your race?” (1 = not at all to 7 = very much); these two items were averaged (r = .98, p < .001; Stock et al., 2011).

Anger

Three items representing externalizing reactions (anger; angry, upset, mad; [1 = not at all to 5 = extremely] were averaged (α = .94).

Substance use word association

Participants were shown 34 prompt words, randomly presented one at a time, and instructed to fill in the first word that came to their minds (Gibbons et al., 2012). Of the 34 prompt words, 14 were double entendre with substance associations (e.g., pot, line, draft) and 5 additional words or phrases were also associated with substances (party, Friday night, fun, relaxation, being social). Two raters, blind to experimental condition, coded each participant’s response to all words in terms of its relation to substances (0 = not related, 1 = related); agreement between them was high (intra-class correlation = .95). The number of substance-related words for each participant was summed.

Substance use willingness

The alcohol willingness measure began with a hypothetical scenario: “Suppose that you are at a party. After several drinks you begin to feel that you may have had enough, and you are getting ready to leave. Then a friend you haven’t seen for a while starts talking to you and offers to get you another drink…Under these circumstances, how willing would you be to do: 1)…Stay and have just one or two more drinks? 2)…Stay and continue to drink (more than one or two drinks)? 3)…Drink until you were drunk?” The drug willingness section began with a similar scenario: “Suppose you were with some friends at a party and a group of people at the party are using drugs (e.g., marijuana)… How willing would you be to 1) try some of the drugs? 2) use enough to get high? 3) buy some to use at a later time?” Two additional items asked “How willing would you be to get drunk [use marijuana] in the next 3 months?” All eight items were accompanied by a 7-point scale from 1 = not at all to 7 = very (Gibbons et al., 2004; Stock et al., 2013); items were averaged (α = .83).

Results

Means and Correlations

85% percent of participants reported drinking alcohol and 46% reported using marijuana in the past 6 months. Table 1 presents the means, SDs, and correlations for the primary measures. Females reported less marijuana use and substance use willingness (both ps < .01). Past use and use cognitions were all highly correlated (all ps < .01). Willingness was positively correlated with perceived exclusion and discrimination, as well as greater anger (all ps < .05).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | . | |||||||||

| 2. Age | .02 | . | ||||||||

| 3. Student status | .07 | −.29*** | . | |||||||

| 4. Alcohol Use | −.10 | .27*** | −.09 | . | ||||||

| 5. Marijuana Use | −.32*** | −.09 | −.08 | .18** | . | |||||

| 6. Perceived Discrimination | .01 | −.07 | −.10 | .03 | .08 | . | ||||

| 7. Perceived Exclusion | .05 | .03 | −.06 | .13* | .06 | .67*** | . | |||

| 8. Anger | .01 | −.02 | −.02 | .08 | .08 | .52*** | .54*** | . | ||

| 9. Word Association | −.11 | −.02 | .01 | .30*** | .23** | .03 | .02 | .08 | . | |

| 10. Substance Use BW | −.19** | .09 | −.09 | .47*** | .64*** | .15* | .14* | .20** | .34*** | . |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean | .50 | 22.26 | .48 | 3.60 | 2.49 | 3.04 | 2.90 | 1.78 | 4.66 | 2.71 |

| SD | 1.30 | 1.70 | 2.10 | 2.05 | 1.53 | 1.09 | 2.82 | 1.33 | ||

| Range | 0–1 | 18–25 | 0–1 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 0–16 | 1–6.38 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001; Gender: 0 = Male, 1 = Female; Student status: 0 = not enrolled, 1 = enrolled. BW = behavioral willingness.

Plan of Analyses

Bonferroni-adjusted general linear model (GLM) analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted to investigate the extent to which racial exclusion (versus inclusion), writing condition (neutral vs. self-affirmation vs. racial-affirmation), and their interaction influenced affect and substance use cognitions. As expected, excluded participants reported significantly greater levels of perceived exclusion, discrimination, and anger (all ps < .05; see below for means). Preliminary analyses indicated there was only one significant simple effect between the three writing conditions among the included participants (for substance use willingness; see Table 2). In addition, when examining the simple effects within writing condition between included versus excluded participants, participants reported higher discrimination, exclusion, and anger when excluded versus included, regardless of writing condition (all ps < .001). There was one unexpected significant effect on substance use willingness among the self-affirmed participants, with excluded participants reporting lower willingness (M = 2.62) compared to included participants (M = 2.92; p = .05; 95% CI for differences [.03, .85]). Thus, based on our hypotheses and these findings, we focus below on the simple effects of writing condition among participants in the exclusion condition (see Table 3). All analyses controlled for age, gender, and student status, as well as other past behaviors relevant to the outcome variable of interest (see below). Only significant covariates are reported.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Errors for manipulation checks, affect, word associations, and behavioral willingness by writing condition, among included participants only.

| Racial-Affirmation

|

Self-Affirmation

|

Neutral

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Perc. Discrimination | 2.11a | 0.29 | 2.03a | 0.29 | 2.25a | 0.29 |

| Perc. Exclusion | 1.79a | 0.16 | 1.58a | 0.16 | 1.96a | 0.16 |

| Anger | 1.34a | 0.16 | 1.22a | 0.56 | 1.53a | 0.16 |

| Word Associations | 4.52a | 0.42a | 4.83a | 0.44a | 5.36a | 0.43a |

| Substance Use BW | 2.42a | 0.15 | 2.97b | 0.15 | 2.74a,b | 0.15 |

Note: Values that do not share a subscript in the same line differ significantly at the p < .05 level. BW = behavioral willingness.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Errors for manipulation checks, affect, word associations, and behavioral willingness by writing condition, among excluded participants only.

| Racial-Affirmation n = 39 |

Self-Affirmation n = 37 |

Neutral n = 40 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Perc. Discrimination | 3.69a | .30 | 3.84a,b | .30 | 4.55b | .29 |

| Perc. Exclusion | 4.04a | .19 | 4.17a | .20 | 3.99a | .19 |

| Anger | 1.91a | .17 | 2.10a,b | .17 | 2.49b | .16 |

| Word Associations | 3.96a | .45 | 4.98b | .45 | 5.07b | .42 |

| Substance Use BW | 2.42a | .15 | 2.62a,b | .15 | 2.99b | .15 |

Note: Values with different subscripts in the same row differ significantly at the p < .05 level according to simple contrasts. BW = behavioral willingness.

Preliminary Analyses and Manipulation Checks

A series of GLM ANCOVAs examined whether there were significant differences for the control variables (past substance use, school status, age) by condition. No significant effects were found (Fs < 1.8, ps > .2). An ANCOVA was also run examining the main effects of Exclusion (0 = inclusion, 1 = exclusion), Writing Condition, and the Exclusion × Writing interaction on perceived exclusion. Excluded participants reported greater exclusion (M = 4.09, SE = .09) than included participants (M = 1.78, SE = .09; F(1, 242) = 296.62, p < .001, ηp2 = .57); the Writing main effect F(2, 242) = .20, p = .82, ηp2 = .00, and Exclusion by Writing interaction were not significant F(2, 242) = 1.64, p = .20, ηp2 = .01. An ANCOVA was also run on perceived discrimination. Excluded participants reported greater perceived discrimination (M = 4.13) than included participants (M = 2.13; F(1, 242) = 63.58, p < .001, ηp2 = .23). Once again, the Writing condition main effect F(2, 242) = 1.34, p = .26,, ηp2 = .01, and Exclusion × Writing interaction F(2, 242) = .34, p = .68, ηp2 = .00, were not significant. However, among the excluded participants, those in the racial-affirmation condition reported significantly lower levels of perceived discrimination (M = 3.68) compared to those in the neutral writing condition (M = 4.55; p = .037; 95% CI for differences [.05, 1.67]). Self-affirmed participants reported marginally lower levels compared to the neutral group (M = 3.84; p = .08; CI [−1.4, .25]).

Anger

Excluded participants reported higher levels of anger (M = 2.17, SE = .09) than did included participants (M = 1.36, SE = .09; F(1, 240) = 38.34, p < .001, ηp2 = .15). A significant main effect for writing condition was revealed (F(2, 240) = 3.68, p < .03, ηp2 = .03). Simple effects showed that participants in the racial-affirmation condition reported lower levels of anger compared to those in the neutral condition (Ms 1.63 vs. 2.11; p < .05, CI [.002, .76]). Anger levels in the self-affirmation condition were marginally lower than the neutral group (M = 1.68; p < .08; CI [−.03, .74]) and did not differ significantly from the racially affirmed group (p > .5). The Exclusion × Writing condition interaction was not significant (F(2, 240) = .52, p = .59, ηp2 = .01). More relevant to the central hypothesis, among excluded participants, those in the racial-affirmation condition reported significantly lower levels of anger (M = 1.91) compared to those in the neutral condition (M = 2.49; p = .011; 95% CI [.13, 1.02]). Anger among the self-affirmed group (M = 2.10) did not differ from the racial-affirmation (p = .43; 95% CI [−.64, .28]) or neutral groups (p = .09; 95% CI [−.06, .85]).3

Substance Use Risk Cognitions

Substance use word associations

95% of participants reported at least one substance-relevant response word, with 50% reporting four or more. Past alcohol and drug use both predicted a greater number of substance use word associations (all ps < .03). The main effect for Exclusion (F(2, 229) = 1.10, p = .3, ηp2 = .01) and the 2-way interaction (F(2, 229) = .94, p =.4, ηp2 = .01) were not significant. The main effect for writing condition was significant (F(2, 229) = 3.88, p < .03, ηp2 = .04). Simple effects revealed that participants in the racial affirmation condition reported significantly fewer substance word associations compared to those in the self-affirmation condition (Ms 4.04 vs. 5.17; p < .03, CI [−2.19, −.07]). No other simple effects were significant (ps > .1). Among the excluded participants, as expected, those who racially affirmed reported fewer substance-related words (M = 3.56) compared to those in both the neutral (M = 5.07; p < .02, CI [−2.74, −.28]) and self-affirmation conditions (M = 4.98; p < .03, CI [−2.69, −.15]). The neutral and self-affirmation groups did not differ (p = .88, CI [−1.1, 1.3]).

Substance use willingness

Once again, alcohol and drug use in the past 6 months were significant covariates (ps < .001). The main effects for exclusion condition (F(2, 240) = 1.66, p = .2, ηp2 = .01) and writing condition (F(2, 240) = 2.66, p =.07, η2 p= .03) were not significant. However, a significant Exclusion × Writing condition interaction emerged (F(2, 240) = 4.42, p < .02, ηp2 = .04). Among the included participants, those in the racial-affirmation condition reported significantly lower levels of willingness compared to those in the self-affirmation condition (Ms 2.42 vs. 2.97; p < .01, CI [.14, .96]). However, willingness in the neutral group (M = 2.74) did not differ significantly from either affirmation group (both ps > .13). Within the exclusion condition, participants who racially affirmed reported significantly lower levels of willingness to use (M = 2.42) compared to those in the neutral condition (M = 2.99; p < .01; CI [.15, .98]). Self-affirmed participants reported marginally lower levels of willingness to use (M = 2.62) compared to the neutral group (p < .08; CI [−.04, .78]), but did not significantly differ from the racial-affirmation group (p = .36; CI [−.22, .62]).4,5

In summary, significant differences in the writing conditions were primarily evident among participants who were expected to be the most affected: those who were (racially) excluded. Overall, the largest differences and most consistent pattern of effects were found between the neutral and racial-affirmation writing conditions: young Black adults who engaged in racial-affirmation after experiencing exclusion by White peers reported significantly lower levels of perceived discrimination, anger, and substance use willingness. Racially-affirmed participants in the excluded condition also reported significantly fewer substance-related word associations compared to the two other groups.

Mediation

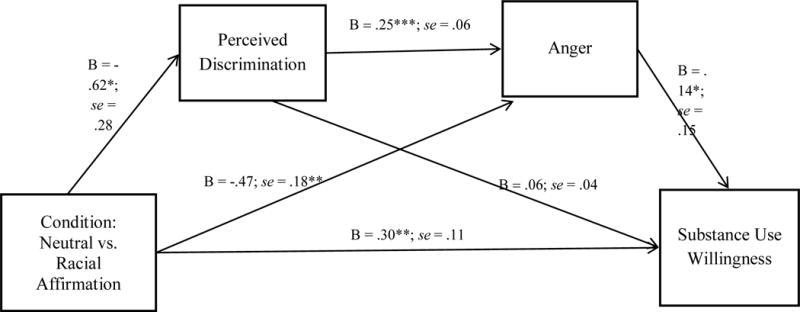

The ANCOVAS revealed that the largest differences in our results were on anger, perceived discrimination, and substance use willingness and were, as expected, among the racially-excluded participants and between the racial-affirmation and neutral writing groups. To examine whether the effect of racial-affirmation versus neutral writing on substance use willingness among excluded participants was mediated by lowered levels of perceived discrimination and anger, a bootstrap test of multiple mediation (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) was conducted using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (see Hayes, 2012; Model 6). Standard errors for indirect effects were bootstrapped (1000 samples). Both mediators (perceived discrimination and anger) were examined in the same model and both direct and indirect (mediation) effects were examined. Contrast coding was used to compare condition effects in the model. Because the focus was on the racially affirmed versus the neutral writing conditions, the model compared these two conditions (coded: 0 = self-affirmation, 1 = racial-affirmation, −1 = neutral). Age, gender, student status, and past use were included as covariates. As expected, among the excluded participants, direct effects indicated racial-affirmation (vs. neutral writing) was associated with lower levels of perceived discrimination, anger, and willingness (ps < .05; see Figure 1 for standardized coefficients and standard errors for effects). Two indirect effects were significant. The first was the indirect path from condition to willingness through both perceived discrimination and anger. The bias-corrected 95% CI for the indirect path from condition to willingness through perceived discrimination and then anger did not contain zero (CI: .007, .16; B = .02; se = .02). The second was the indirect effect of anger alone on willingness (CI: .008, .08; B = .02; se = .02). However, the indirect effect of perceived discrimination alone on willingness was not significant (CI: −.008, .13; B = .02; se = .03). Thus, as predicted, the relation between racial-affirmation and willingness was mediated by anger. Finally, although not predicted, racial-affirmation was also associated with reduced perceptions of discrimination, which in turn, predicted reduced anger and then reduced substance use willingness.

Figure 1.

Mediation by perceived discrimination and anger between racial-affirmation (vs. neutral) writing conditions and substance use willingness among excluded participants. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Discussion

Consistent with previous research, Black young adults who were excluded versus included by White peers reported higher levels of perceived racial discrimination (cf., Stock et al., 2011; 2013). Both exclusion and resulting perceptions of discrimination were associated with higher levels of anger. Our findings offer further evidence that anger mediates the relation between racial exclusion and willingness to use substances (Gerrard et al., 2017; Gibbons et al., 2010; Stock et al., 2011). In addition, the present study provides evidence that racial affirmation can counteract the negative effect of race-based exclusion on perceptions of discrimination, anger, and resulting substance use vulnerability. Therefore, in the face of discrimination involving a particular (racial) identity, affirming that same identity reduces the negative effects of racial exclusion. In contrast, self-affirmation was not more effective than a neutral writing at reducing use cognitions. Thus, affirmations based within the same domain that is being threatened can be protective against health-related threats. These findings are consistent with tenets from both self-affirmation and social identity theory: social threats based on one’s identity can lead to negative affect, however, this can be counteracted by making positive aspects of the identity salient (Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Tajfel & Turner, 1986).

Why is Racial-Affirmation Effective in Reducing Use Cognitions?

There are several reasons why racial-affirmation may be protective. First, as predicted, racial-affirmation was associated with lower levels of anger. Previous research has suggested that substance use reflects a coping effort to mute the anger and stress that results from discrimination (Gerrard et al., 2012). Secondly, in this study, racial-affirmation was associated with reduced attributions of exclusion to prejudice, which in turn, were associated with less anger. Although not hypothesized, this is potentially a meaningful finding in that few studies thus far have demonstrated that perceptions of discrimination can be reduced. One possible reason why is that affirmation might enhance attributions of negative treatment to more external factors (Crocker, et al., 1991). Focusing on positive aspects of one’s race and/or expanding positive self-view may reduce the extent to which the individual believes the exclusion was due to their race versus other factors (Branscombe et al., 1999; Neblett et al., 2012).

Another reason racial-affirmation might be effective is that, in general, RI is associated with more positive feelings about the self as a minority and enhanced feelings of connection and belonging (e.g., Phinney et al., 1997; Sellers & Shelton, 2003), which may facilitate maintaining a positive sense of self and feelings of support when faced with a race-based threat. Racial affirmations may enhance feelings of connectedness, support, pride, and psychological well-being via enhanced feelings of social identity (Greenaway et al., 2015). It may also be the case that when their racial group is made salient, Black young adults are motivated to present themselves as positive exemplars of their social group and debunk stereotypes of African Americans by not engaging in substance use (Pugh & Bry, 2007). Finally, affirmation processes, in general, and specific to enhancing group-based identity, may help counteract self-control depletion and feelings of a loss of personal control (Greenaway et al., 2015; Schmeichel & Vohs, 2009) that results from discriminatory experiences and are associated with increased substance use (Gibbons et al., 2012). Additional studies are needed to explore these relations. It is important to note that our participants’ affirmations, although all positive, varied in their focus to some degree. Our recent research suggests that Black young adults who are excluded by Whites, versus Blacks, report higher levels of perceived discrimination and substance use cognitions and that racial affirmation specific to positive Black role models is more effective than writing about general belonging in reducing this association. Future research could further examine whether racial affirmation is effective via enhancing collective self-esteem and if this is specific to racial versus general social exclusion (Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992). Nonetheless, there could be other situations in which self-affirmation is more effective; this empirical question is worth pursuing.

Intervention Implications

Our study suggests racial-affirmation techniques may be helpful in buffering against negative affect and substance use as coping that may result from experiences of racial exclusion among Black young adults. The current results also illustrate the potential importance of ethnic-based approaches to minority substance use prevention. The finding that RI affirmation is protective against the negative effects of racial exclusion suggests that enhancing and discussing positive feelings associated with one’s racial/ethnic identity can help reduce the pain and potential negative health consequences of rejection from the majority (Brondolo et al., 2009; Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002). Although prevention programs have not focused specifically on enhancing RI or affirming positive aspects of one’s identity, several programs include culture-promoting components that likely play a role in enhancing aspects of a positive RI (e.g., Stevenson, 2003). Substance prevention programs, such as SAAF, which encourage Black adolescents to be proud of their race, in part, because Black adolescents use substances less than Whites, can reduce positive attitudes toward use and also decrease willingness and, in turn, substance use over time (Brody et al., 2004; Gerrard et al., 2006). Having Black young adults engage in affirmation processes may be a feasible and effective strategy to use in future prevention/intervention efforts among those who share a common value or group identity.

Our results also indicate that researchers should continue to focus on malleable factors that can serve as targets of interventions, such as helping young adults engage in positive ways of coping with the negative affect that can result from discrimination experiences (Brody et al., 2006; Gibbons et al., 2012; Gonzales et al., 2014; Wills, et al., 2007). Several of these intervention programs include aspects of positive parenting and racial socialization. Both of these mechanisms have been associated with reduced feelings of anger and substance use vulnerability (Gibbons et al., 2012; 2015). The combination of positive racial socialization and identity mechanisms reduces the effects of discrimination on substance use vulnerability via decreasing anger and attributions of racism, enhancing positive feelings about the self and feelings of self-control, and increasing positive coping strategies (Neblett et al., 2010).

Limitations/Future directions

There are several limitations of the study that should be discussed, some of which suggest possible future research directions. First, discriminatory experiences outside of the lab may produce different reactions in conjunction with affirmation. These experiences can range in severity and are more chronic than acute. Thus, additional research is needed that extends racial-affirmation techniques and examines how these impact everyday experiences of identity threat. These interventions should also examine the most effective timing of the affirmations (e.g., before or after identity threat) and the effects of having differing numbers of affirmations completed over a longer period of time (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). In addition, longitudinal research is needed to explore whether “naturally occurring” affirmation experiences can also reduce the negative effects of identity threat. For example, many of our participants wrote about the election of President Obama in their racial-affirmation essay. Prominent and positive events regarding one’s social identity, especially when reflected upon, might be protective against identity-threats that might occur during time frames close to those events. On a related note, when given a choice, many participants chose to affirm in domains related to social relationships (Creswell et al., 2007) and there are several ways in which an individual might identify with their racial/ethnic group. Thus, a next step is to explore different forms of racial- affirmations.

Finally, previous studies suggest that feelings of racial-group belonging, affirmation, and positive affect and evaluations, may be more likely to act as a buffer than other dimensions of RI (Greene et al., 2006; Rivas-Drake et al., 2014; Stock et al., 2011). However, different dimensions may be influenced differently depending on the immediate social context and the outcomes being examined. For example, previous studies have suggested that programs focusing on RI affirmation and belonging may be especially effective for Black young adults in predominantly White neighborhoods or peer environments where they are more likely to report experiences of discrimination (Brody et al., 2006; Stock et al., 2013; Szalacha et al., 2003).

Conclusion

The present results provide experimental evidence that racial-affirmation can protect against increases in substance use vulnerability of Black young adults created by an experience of racial exclusion (perceived as racial discrimination). In addition, these results demonstrate that affirmed RI is protective against substance use cognitions, in part, because it can reduce perceptions of discrimination and feelings of anger. Self-affirmation did not have the same protective effects against substance use vulnerability among excluded participants. These findings are important for several reasons, including the fact that the negative consequences of anger-focused and use-as-coping cognitions can have long-term impacts on the health and well-being of Black young adults. These findings have implications for interventions, specifically, the utility and potential of (enhanced) RI in the face of perceived racial discrimination.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIDA/NIH (R21DA034290-02)

Footnotes

Participants in the racial-affirmation group tended to write about positive feelings, historical events, and experiences with being Black and part of the Black community. 42% wrote about a respected Black figure (e.g., President Obama, Martin Luther King Jr., in addition to positive feelings about their race). Another common topic was overcoming adversity both in the past and in present time. The most common topics in the self-affirmation condition were positive personal characteristics (e.g., self-identity and values), personal accomplishments (e.g., graduating high school or college, doing well at a job), and helping.

Participants were also asked about hard drug use (e.g., heroin, crack/cocaine, injection drug use). Only 4% reported using any drugs other than marijuana in the past 6 months.

We also included a measure of sadness. Excluded participants reported greater levels of sadness than did included participants (M = 2.15, SE = .08 vs. M = 1.44, SE = .08; F(1, 240) = 40.34, p < .001). In addition, self-affirmed participants reported significantly lower levels of sadness compared to those in the neutral condition (Ms 1.63 vs. 2.01; p < .05). Sadness levels did not differ between self-affirmed and racially-affirmed groups (ps >

We also had a measure of willingness to engage in risky “prosocial” behaviors (letting a friend cheat off you in class, speeding in your car to get a friend to the airport on time, and helping someone in danger). Excluded participants reported greater prosocial risky willingness. There were no significant effects between writing conditions (ps > .05).

When we examined potential gender differences in condition effects on our DVs, the only significant findings were with substance use willingness. Although the pattern of findings was the same for both genders, among the excluded participants, racial-affirmation (compared to the neutral and self-affirmation groups) was associated with significantly lower willingness among the males (ps < .05) and marginally lower willingness among the females (ps < .1).

Contributor Information

Michelle L. Stock, The George Washington University

Frederick X. Gibbons, University of Connecticut

Janine B. Beekman, The George Washington University

Kipling D. Williams, Purdue University

Laura S. Richman, Duke University

Meg Gerrard, University of Connecticut.

References

- Aklin WM, Moolchan ET, Luckenbaugh DA, Ernst M. Early tobacco smoking in adolescents with externalizing disorders: inferences for reward function. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;6:750–755. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Wallace JM., Jr Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between parental education and substance use among US 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students: Findings from the Monitoring the Future Project. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(2):279–285. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Jacobs DR, Williams DR, Pletcher MJ, Houston TK, Kiefe CI. Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adults Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;166(9):1068–1079. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(1):135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair L, Chen YF. The Strong African American Families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75(3):900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen YF, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, ver Halen NB, Pencille M, Beatty D, Contrada RJ. Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:64–88. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Hausmann LR, Jhalani J, Pencille M, Atencio-Bacayon J, Kumar A, Schwartz J. Dimensions of perceived racism and self-reported health: examination of racial/ethnic differences and potential mediators. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;42(1):14–28. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9265-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJ, Taylor BC, Phelan S, Spoont M, Ryn M, Hausmann LRM, Gordon HS. A brief self-affirmation study to improve the experience of minority patients. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2014;6(2):135–150. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading Causes of Death in Females, 2014. 2017 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/women/lcod/2014/black/index.htm.

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(2):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow RM, Tiedens LZ, Govan CL. Excluded emotions: The role of anger in antisocial responses to ostracism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44(3):896–903. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, Sherman DK. The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology. 2014;65:333–371. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, Garcia J, Purdie-Vaughns V, Apfel N, Brzustoski P. Recursive processes in self-affirmation: Intervening to close the minority achievement gap. Science. 2009;324(5925):400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1170769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JD, Lam S, Stanton AL, Taylor SE, Bower JE, Sherman DK. Does self-affirmation, cognitive processing, or discovery of meaning explain cancer-related health benefits of expressive writing? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:238–250. doi: 10.1177/0146167206294412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Voelkl K, Testa M, Major B. Social stigma: The affective consequences of attributional ambiguity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60(2):218–228. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, White HR, Mun EY, Cronley CC, Lee C. Racial differences in trajectories of heavy drinking and regular marijuana use from ages 13 through 24 among African-American and White males. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121(1–2):118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French K, Finkbiner R, Duhamel L. Patterns of Substance Use among Minority Youth and Adults in The United States: An overview and synthesis of national survey findings. Department of Health and Human Services; Fairfax, VA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Brody GH, Murry VM, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA. A theory-based dual-focus alcohol intervention for preadolescents: The Strong African American Families Program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(2):185–195. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Fleischli M, Cutrona C, Stock ML. Moderation of the effects of discrimination-induced affective responses on health outcomes. Psychology and Health. 2017 doi: 10.1080/08870446.2017.1314479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Stock ML, Roberts ME, Gibbons FX, O’Hara RE, Weng CY, Wills TA. Coping with racial discrimination: the role of substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):550–560. doi: 10.1037/a0027711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Stock ML. Perceived racial discrimination and health behavior: mediation and moderation. In: Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, editors. Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health. Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Finneran S. The prototype-willingness model. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting and Changing Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models. 3rd. Open Univeristy Press; Berkshire, UK: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Yeh H, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Cutrona C, Simons RL, Brody GH. Early experience with discrimination and conduct disorder as predictors of subsequent drug use: A critical period analysis. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Etcheverry PE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Kiviniemi M, O’Hara RE. Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: what mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99(5):785–801. doi: 10.1037/a0019880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, O’Hara RE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Wills TA. The erosive effects of racism: reduced self-control mediates the relation between perceived racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(5):1089–1104. doi: 10.1037/a0027404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Kingsbury JH, Weng CY, Gerrard M, Cutrona C, Wills TA, Stock M. Effects of perceived racial discrimination on health status and health behavior: A differential mediation hypothesis. Health Psychology. 2014;33(1):11–19. doi: 10.1037/a0033857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86(4):517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Lau A, Murry VM, Pina A, Barrera M. Developmental Psychopathology. 3rd. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. Culturally adapted preventive interventions for children and youth. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SA, Williams KD, Carter-Sowell AR. The psychological sting of stigma: The costs of attributing ostracism to racism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46(4):612–618. [Google Scholar]

- Gray CM, Montgomery MJ. Links between alcohol and other drug problems and maltreatment among adolescent girls: Perceived discrimination, ethnic identity, and ethnic orientation as moderators. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36(5):449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenaway KH, Haslam SA, Cruwys T, Branscombe NR, Ysseldyk R. From" we" to" me": group identification enhances perceived personal control with consequences for health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2015;109(1):53–74. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among African American, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(2):218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PR, Ferrer R, Klein WMP. The multifaceted role of affect in self-affirmation effects. In: Botti Simona, Labroo Aparna., editors. NA - Advances in consumer research. Vol. 41. Duluth, MN: Association for Consumer Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hartgerink CH, van Beest I, Wicherts JM, Williams KD. The ordinal effects of ostracism: A meta-analysis of 120 Cyberball studies. PloS One. 2015;10(5):e0127002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam SA, Jetten J, Postmes T, Haslam C. Social identity, health and well-being: an emerging agenda for applied psychology. Applied Psychology. 2009;58(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. PROCESS SPSS Macro [Computer Software and Manual] 2012 Available from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process.pdf.

- Jones SC, Neblett EW. Racial–Ethnic protective factors and mechanisms in psychosocial prevention and intervention programs for African American youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2016;19(2):134–161. doi: 10.1007/s10567-016-0201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Schaffran C, Hu MC, Thomas Y. Age-related differences in cigarette smoking among whites and African-Americans: evidence for the crossover hypothesis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118(2):280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Vo T, Wall MM, Caetano R, Suglia SF, Martins SS, Hasin D. Racial/ethnic differences in use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana: Is there a cross-over from adolescence to adulthood? Social Science & Medicine. 2015;124:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2016;61(4):1–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krank MD, Schoenfeld T, Frigon AP. Self-coded indirect memory associations and. Behavior Research Methods. 2010;42(3):733–738. doi: 10.3758/BRM.42.3.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN, Hager C. The CBHSQ Report: February 21, 2013. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2013. Need for and receipt of substance use treatment among Blacks. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhtanen R, Crocker J. A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18(3):302–318. [Google Scholar]

- Martens A, Johns M, Greenberg J, Schimel J. Combating stereotype threat: The effect of self-affirmation on women’s intellectual performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;42(2):236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Masten CL, Telzer EH, Eisenberger NI. An fMRI investigation of attributing negative social treatment to racial discrimination. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23(5):1042–1051. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Klein WM. Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self and Identity. 2006;5(4):289–354. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Kost-Smith LE, Finkelstein ND, Pollock SJ, Cohen GL, Ito TA. Reducing the gender achievement gap in college science: A classroom study of values affirmation. Science. 2010;330(6008):1234–1237. doi: 10.1126/science.1195996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(3):295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Smalls CP, Ford KR, Nguyên HX, Sellers RM. Racial socialization and racial identification: Messages about race as precursors to African American racial identity. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2009;38(2):189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Terzian M, Harriott V. From racial discrimination to substance use: the protective effects of racial socialization. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4:131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure a new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Cantu CL, Kurtz DA. Ethnic and American identity as predictors of self-esteem among African American, Latino, and White adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1997;26(2):165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh LA, Bry BH. The protective effects of ethnic identity for alcohol and marijuana use among African American young adults. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(2):187–193. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivis A, Sheeran P, Armitage CJ. Augmenting the theory of planned behaviour with the prototype/willingness model: Predictive validity of actor versus abstainer prototypes for adolescents’ health-protective and health-risk intentions. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11(3):483–500. doi: 10.1348/135910705X70327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, Yip T. Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development. 2014;85(1):40–57. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooke SE, Hine DW, Thorsteinsson EB. Implicit cognition and substance use: A meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(10):1314–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeichel BJ, Vohs KD. Self-affirmation and self-control: Affirming core values counteracts ego depletion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96(4):770–782. doi: 10.1037/a0014635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR. The internal and external causal loci of attributions to prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:620–628. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003:302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(5):1079. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SA, Chavous TM. Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2(1):18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Hartson KA, Binning KR, Purdie-Vaughns V, Garcia J, Taborsky-Barba S, Cohen GL. Deflecting the trajectory and changing the narrative: how self-affirmation affects academic performance and motivation under identity threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104(4):591–618. doi: 10.1037/a0031495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart Richman L, Leary MR. Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: a multimotive model. Psychological Review. 2009;116(2):365–383. doi: 10.1037/a0015250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, editor. Playing with anger: Teaching coping skills to African American boys through athletics and culture. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, Praeger; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stock ML, Gibbons FX, Walsh LA, Gerrard M. Racial identification, racial discrimination, and substance use vulnerability among African American young adults. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37(10):1349–1361. doi: 10.1177/0146167211410574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock ML, Gibbons FX, Peterson LM, Gerrard M. The effects of racial discrimination on the HIV-risk cognitions and behaviors of African American adolescents and young adults. Health Psychology. 2013;32(5):543–550. doi: 10.1037/a0028815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock ML, Gibbons FX, Beekman JB. Social exclusion and substance use cognitions and behaviors. In: Kopetz C, Lejuez C, editors. Frontiers in Social Psychology: Addiction. New York, NY: Routledge; 2015. pp. 76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Stock ML, Peterson LM, Molloy BK, Lambert SF. Past racial discrimination exacerbates the effects of racial exclusion on negative affect, perceived control, and alcohol-risk cognitions among Black young adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2017;40(3):377–391. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9793-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SurveyMonkey LLC. SurveyMonkey®. Palo Alto (CA): SurveyMonkey, LLC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA, Erkut S, Garcia Coll C, Fields JP, Alarcon O, Ceder I. Perceived discrimination and resilience. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 414–435. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin LW, editors. Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Thush C, Wiers RW, Ames SL, Grenard JL, Sussman S, Stacy AW. Apples and oranges? Comparing indirect measures of alcohol-related cognition predicting alcohol use in at-risk adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:587–591. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd J, Kothe E, Mullan B, Monds L. Reasoned versus reactive prediction of behaviour: A meta-analysis of the prototype willingness model. Health Psychology Review. 2016;10(1):1–24. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.922895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR, Hawi D, Van Laar C, Levin S. Cross-ethnic friendships, perceived discrimination, and their effects on ethnic activism over time: A longitudinal investigation of three ethnic minority groups. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2012;51:257–272. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lettow B, de Vries H, Burdorf A, van Empelen P. Quantifying the strength of the associations of prototype perceptions with behaviour, behavioural willingness and intentions: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review. 2016;10(1):25–43. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.941997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Murry VM, Brody GH, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Walker C, Ainette MG. Ethnic pride and self-control related to protective and risk factors: Test of the theoretical model for the Strong African American Families program. Health Psychology. 2007;26(1):50–59. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:425–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Cheung CK, Choi W. Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(5):748–762. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Stoolmiller M. The role of self-control in early escalation of substance use: a time-varying analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:986–997. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witbrodt J, Mulia N, Zemore SE, Kerr WC. Racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol-related problems: Differences by gender and level of heavy drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(6):1662–1670. doi: 10.1111/acer.12398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71(6):1197–1232. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]