ABSTRACT

Antibiotic resistance is a growing crisis and a grave threat to human health. It is projected that antibiotic-resistant infections will lead to 10 million annual deaths worldwide by the year 2050. Among the most significant threats are carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), including carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP), which lead to mortality rates as high as 40 to 50%. Few treatment options are available to treat CRKP, and the polymyxin antibiotic colistin is often the “last-line” therapy. However, resistance to colistin is increasing. Here, we identify multidrug-resistant, carbapenemase-positive CRKP isolates that were classified as susceptible to colistin by clinical diagnostics yet harbored a minor subpopulation of phenotypically resistant cells. Within these isolates, the resistant subpopulation became predominant after growth in the presence of colistin but returned to baseline levels after subsequent culture in antibiotic-free media. This indicates that the resistance was phenotypic, rather than due to a genetic mutation, consistent with heteroresistance. Importantly, colistin therapy was unable to rescue mice infected with the heteroresistant strains. These findings demonstrate that colistin heteroresistance may cause in vivo treatment failure during K. pneumoniae infection, threatening the use of colistin as a last-line treatment for CRKP. Furthermore, these data sound the alarm for use of caution in interpreting colistin susceptibility test results, as isolates identified as susceptible may in fact resist antibiotic therapy and lead to unexplained treatment failures.

KEYWORDS: Klebsiella, antibiotic resistance, clonal heteroresistance, colistin, heteroresistance

IMPORTANCE

This is the first report of colistin-heteroresistant K. pneumoniae in the United States. Two distinct isolates each led to colistin treatment failure in an in vivo model of infection. The data are worrisome, especially since the colistin heteroresistance was not detected by current diagnostic tests. As these isolates were carbapenem resistant, clinicians might turn to colistin as a last-line therapy for infections caused by such strains, not knowing that they in fact harbor a resistant subpopulation of cells, potentially leading to treatment failure. Our findings warn that colistin susceptibility testing results may be unreliable due to undetected heteroresistance and highlight the need for more accurate and sensitive diagnostics.

OBSERVATION

Antibiotic resistance is an increasingly urgent problem, predicted to cause 10 million annual deaths worldwide by the year 2050 (1). Klebsiella spp., including K. pneumoniae, are responsible for ~10% of nosocomial infections in the United States (2), including urinary tract, bloodstream, and soft tissue infections (3). Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) is one of the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), an emerging cause of antibiotic-resistant, health care-associated infections. CRE were listed as one of the most urgent antibiotic resistance threats by the CDC and WHO (4, 5). In part due to the difficulty of effectively treating infections with CRE, mortality rates can be as high as 40 to 50% (6). These infections are a worldwide problem, with recent reports indicating that CRE are widespread in the United States (7), Europe (8), and China (9). Unfortunately, resistance to “last-line” drugs, such as colistin, is emerging in CRKP strains, and in some cases, isolates are resistant to all antibiotics tested (10). Here, we describe the identification of two multidrug-resistant CRKP isolates exhibiting colistin heteroresistance, a phenomenon in which only a minor subpopulation of genetically identical cells is phenotypically resistant. Since the frequency of the resistant subpopulation is exceedingly low in these isolates, they are not detected as being colistin resistant by clinical diagnostic tests.

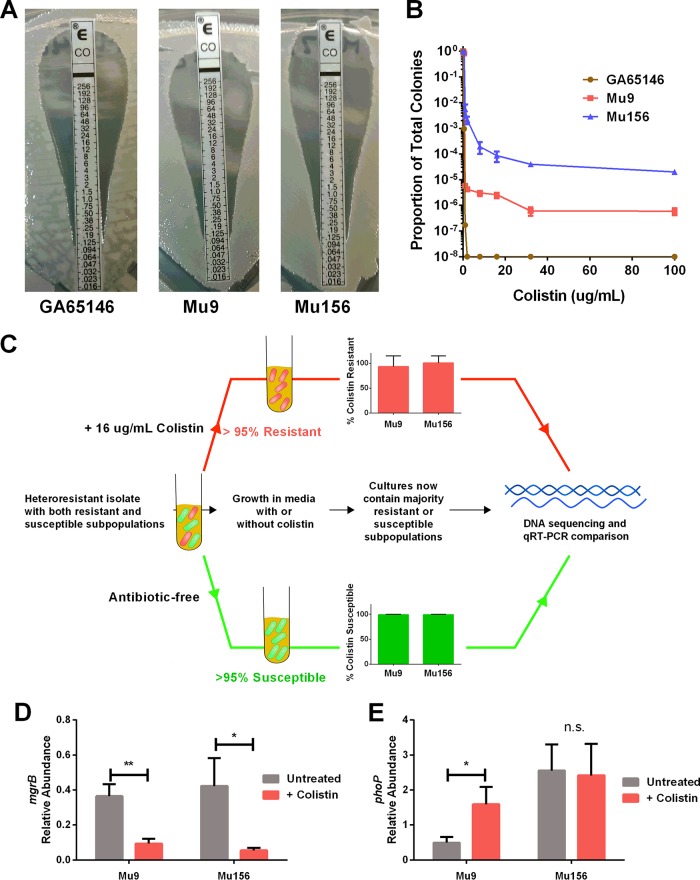

Two CRKP urine isolates (Mu9 and Mu156) were collected from different patients in Atlanta, GA, area hospitals as part of the Multi-site Gram-Negative Surveillance Initiative (MuGSI), a nationwide surveillance network for CRE hospital isolates. Isolates were grown from single colonies and frozen at −80°C prior to the study. Mu9 and Mu156 were confirmed as being genetically distinct by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (using XbaI-digested total DNA and separated by electrophoresis on a Chef-DR III apparatus [Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA] at 200 V [6 V/cm] with a 90-s switch time for 23 h) (data not shown). Both isolates were resistant to nearly all antibiotics tested, including all carbapenems and some aminoglycosides (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). PCR for various resistance genes revealed several beta-lactamases in each isolate, including Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) in both strains (Table S2). Colistin susceptibility testing by broth microdilution (11) in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) using colistin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (MIC of 0.5 µg/ml) and the colistin Etest (BioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France), performed on MH agar (Remel, San Diego, CA) (MIC = 0.125), classified both strains as susceptible to colistin (Fig. 1A). Subsequent examination for susceptibility was performed via population analysis profile (PAP) by plating serial dilutions of bacteria on MH agar (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing various concentrations of colistin. PAP revealed the presence of a minor colistin-resistant subpopulation in each isolate that actively grew on antibiotic up to a concentration of 100 µg/ml. The colistin-resistant subpopulation was present at between 1 in 1,000 and 1 in 1,000,000 CFU at doses of colistin ranging from 2 to 100 µg/ml (Fig. 1B). In contrast, PAP demonstrated that all the cells of a colistin-susceptible control isolate, GA65146, were killed by 2 µg/ml of colistin (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1 .

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae can harbor clinically undetected colistin-resistant subpopulations. (A) Colistin-susceptible isolate GA65146 and the colistin-heteroresistant isolates Mu9 and Mu156 were assayed for colistin resistance using the Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France) method. The MIC is represented by the highest concentration along the strip at which bacteria grow. (B) Population analysis profile of GA65146, Mu9, and Mu156. The proportion of total colonies is the number of CFU able to grow at each concentration of colistin on solid medium divided by the number growing on medium without drug. Heteroresistant isolates exhibit a minor subpopulation that is able to grow on concentrations of colistin above 4 µg/ml. (C) Workflow for genomic and transcriptomic analysis of colistin-susceptible and -resistant subpopulations. Cultures of Mu9 or Mu156 were grown for 18 h in MH broth with or without colistin as indicated. (D and E) Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of mgrB (D) and phoP (E) expression in resistant and susceptible subpopulations of Mu9 and Mu156. Resistant and susceptible subpopulations were enriched as shown in panel C. Relative abundance was calculated by normalizing the expression of each gene to the average expression of two housekeeping genes, 23S and rpsL (n = 6). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significantly different (unpaired t test).

Antibiograms of colistin-heteroresistant K. pneumoniae isolates. Results of MicroScan automated broth microdilution (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA) antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Mu9 and Mu156. MIC results are listed with the interpretive category (S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant) as defined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Antibiotics designated N/A have no defined CLSI MIC breakpoints for K. pneumoniae. Download TABLE S1, PDF file, 0.03 MB (34.7KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Beta-lactam resistance genes in K. pneumoniae isolates. PCR analysis was conducted on Mu9 and Mu156 for 9 common K. pneumoniae resistance genes. Positive genes were those that produced a band at the expected size as assayed by PCR. Download TABLE S2, PDF file, 0.02 MB (22.5KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

It was concerning that broth microdilution and the Etest were unable to detect the colistin-resistant subpopulations in these isolates. The recommended incubation time for both tests is 24 h (11, 12). Extension of the incubation time to 48 h resulted in the accurate identification of resistance by broth microdilution (Fig. S1A), likely because the minor resistant subpopulation had more time to grow out. In contrast, the increased incubation time had no effect on Etest results, which remained negative (Fig. S1B).

An increased broth microdilution incubation time facilitates the detection of colistin heteroresistance. (A, B) The colistin MIC was determined for heteroresistant K. pneumoniae by both broth microdilution (A) and Etest (B) at the recommended 24-h time point or after 48 h of incubation. The dashed line indicates the CLSI breakpoint for resistance to colistin at 4 µg/ml (11). n = 3. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.04 MB (37.4KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

We next studied the dynamics of the resistant subpopulation following colistin treatment. After treatment with 100 µg/ml colistin, the frequency of the resistant subpopulation was significantly increased in each isolate. Subsequent passage in an antibiotic-free medium greatly decreased the frequency of the resistant subpopulation (Fig. S2), suggesting that this population was phenotypically resistant and not the result of a stable genetic mutation. Additionally, this suggests that there is some disadvantage to maintaining a majority colistin-resistant subpopulation. Indeed, it has been previously shown that colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae confers a fitness defect (13). To directly assess whether the resistant and susceptible subpopulations were genetically homogenous, we isolated cultures with majority resistant or susceptible subpopulations by subculturing them in medium containing 16 µg/ml colistin or drug-free medium, respectively (Fig. 1C). This resulted in cultures containing >95% colistin-resistant cells or >95% colistin-susceptible cells (Fig. 1C). We then performed genomic sequencing on both populations using an Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencer for a depth of coverage of >1,000×, revealing that the resistant and susceptible subpopulations were indeed genetically identical, consistent with heteroresistance.

The frequency of the resistant subpopulation increases in the presence of colistin. Heteroresistant K. pneumoniae cells were grown without colistin (pretreatment), subcultured with 100 µg/ml colistin (colistin treated), and then subcultured again without colistin (drug-free subculture). The frequency of the colistin-resistant subpopulation was measured at each step. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.03 MB (31KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

To investigate the phenotypic differences between the resistant and susceptible subpopulations, we quantified the expression of two genes in the PhoPQ two-component system pathway, which is known to mediate colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae. MgrB is a negative regulator of PhoPQ signaling (14), and mgrB expression was lower in resistant cells cultured in colistin than in susceptible cells grown in drug-free medium (Fig. 1D). Additionally, expression of phoP, which is autoinduced when the PhoPQ system is active (15), was increased in colistin-resistant cells of Mu9 compared to its expression in susceptible cells, although this was not observed in Mu156 (Fig. 1E). Taken together, these data are consistent with involvement of the PhoPQ pathway in the resistant subpopulations of both Mu9 and Mu156.

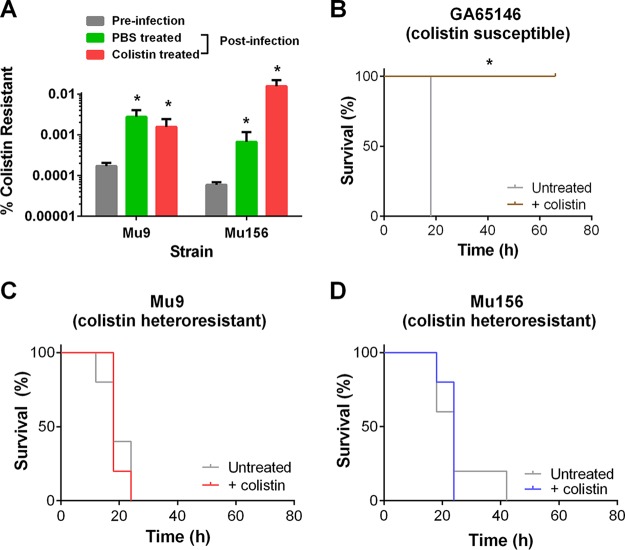

It was unclear whether the minor colistin-resistant subpopulations present in these isolates would have an effect on the outcome of colistin treatment during an in vivo infection. To assess the in vivo relevance of the colistin-resistant subpopulations, we used a mouse model of peritonitis (done in accordance with IACUC protocol #4000046). We infected mice (C57BL/6J; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) intraperitoneally with a lethal dose (3 × 108 CFU) of either of the heteroresistant K. pneumoniae isolates and subsequently left the mice untreated or treated them with colistin after 12 h (20 mg colistin methanesulfonate/kg of body weight [Chem Impex, Wood Dale, IL], given intraperitoneally every 6 h) to simulate infection and subsequent treatment upon clinical presentation. Interestingly, even in the absence of colistin, the frequency of the resistant subpopulations of both heteroresistant isolates increased following 24 h of in vivo infection compared to the frequency produced by the inoculum (Fig. 2A). This may be due to cross-resistance of these cells to host innate immune antimicrobials, such as antimicrobial peptides and reactive oxygen species, as has previously been demonstrated (16). We next assessed the impact of heteroresistance on colistin treatment outcome. Mice infected with the colistin-susceptible strain (GA65146) succumbed to infection in the absence of antibiotic but were rescued by colistin treatment (Fig. 2B). In contrast, mice infected with either of the heteroresistant isolates (Mu9 or Mu156) were unable to survive the infection, even in the presence of colistin (Fig. 2C and D). These data strikingly demonstrate that colistin heteroresistance can lead to in vivo colistin treatment failure for CRKP.

FIG 2 .

K. pneumoniae isolates lead to in vivo colistin treatment failure. (A) Mice were infected intraperitoneally with 3 × 108 CFU of Mu9 or Mu156, treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or colistin (20 mg/kg colistin methanesulfonate) at 12 and 18 h, and then sacrificed at 24 h. Peritoneal lavage fluid was collected and plated onto drug-free medium and medium containing 16 µg/ml colistin to assess percentages of colistin-resistant cells of the heteroresistant strains. The preinfection inoculum (input) was plated similarly (n = 5). *, P < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney test). (B to D) Mice were infected with the colistin-susceptible isolate GA65146 (B) or the colistin-heteroresistant isolate Mu9 (C) or Mu156 (D) and then treated with 20 mg/kg colistin methanesulfonate every 6 h starting at 12 h. Mice were monitored for survival and weight loss and were sacrificed if their weight fell below 80% of their starting weight (n = 5). *, P < 0.05 (Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test).

Concluding remarks.

This is the first report of colistin-heteroresistant K. pneumoniae in the United States. In highly resistant CRE isolates, colistin is a vital last-line treatment option. We show here that in a mouse model of infection, colistin-heteroresistant CRKP isolates fail colistin therapy. This stresses the need to assess the relevance of colistin heteroresistance on the outcome of colistin therapy in human infection, which has yet to be determined.

When highly resistant CRKP strains are isolated in the clinic, testing of last-line antibiotics identifies crucial treatment options. Colistin-heteroresistant isolates, such as the ones reported here, can be misclassified as colistin susceptible, a “very major discrepancy” according to FDA susceptibility testing guidelines (17). Subsequent treatment of these isolates with colistin may then lead to unexplained treatment failure, as was demonstrated in our in vivo mouse model. Thus, the misclassification of colistin susceptibility status wastes critical time and resources and may lead to further infection complications and patient mortality. Clinical laboratories should consider testing for heteroresistance to colistin if this last-line antibiotic is required for treatment. Unfortunately, the current standard test for heteroresistance, the population analysis profile, is time- and labor-intensive, and it is cumbersome for most clinical laboratories to implement. Our findings suggest that broth microdilution with an increased incubation time (48 h) may detect colistin heteroresistance. However, the increased incubation time is a downside in itself, and there is also an increased chance that a culture of susceptible bacteria will become contaminated or that de novo mutant cells will have the time necessary to grow out, leading to an inaccurate identification as resistant. Therefore, novel diagnostics that rapidly and accurately detect colistin heteroresistance are needed.

Taken together, these findings serve to sound the alarm about a worrisome and underappreciated phenomenon in CRKP infections and highlight the need for more sensitive and accurate diagnostics. We suggest that clinical microbiologists and clinicians alike use caution when treating CRKP infections with colistin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Emily Crispell and David Hufnagel for critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

D.S.W. is supported by a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease award and VA Merit award I01BX002788, which were used to fund all experiments. This work was also supported by the Georgia Emerging Infections Program.

Some isolates used in this study were collected as part of the Emerging Infections Program Multi-site Gram-Negative Surveillance Initiative. This work was supported by the Emerging Infections Program and the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Citation Band VI, Satola SW, Burd EM, Farley MM, Jacob JT, Weiss DS. 2018. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae exhibiting clinically undetected colistin heteroresistance leads to treatment failure in a murine model of infection. mBio 9:e02448-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02448-17.

Contributor Information

David A. Hunstad, Washington University.

Scott J. Hultgren, Washington University School of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2016. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, London, United Kingdom: https://amr-review.org/Publications.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, McAllister-Hollod L, Nadle J, Ray SM, Thompson DL, Wilson LE, Fridkin SK, Emerging Infections Program Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use Prevalence Survey Team . 2014. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med 370:1198–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podschun R, Ullmann U. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev 11:589–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization 2017. WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel G, Huprikar S, Factor SH, Jenkins SG, Calfee DP. 2008. Outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection and the impact of antimicrobial and adjunctive therapies. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 29:1099–1106. doi: 10.1086/592412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guh AY, Bulens SN, Mu Y, Jacob JT, Reno J, Scott J, Wilson LE, Vaeth E, Lynfield R, Shaw KM, Vagnone PM, Bamberg WM, Janelle SJ, Dumyati G, Concannon C, Beldavs Z, Cunningham M, Cassidy PM, Phipps EC, Kenslow N, Travis T, Lonsway D, Rasheed JK, Limbago BM, Kallen AJ. 2015. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae in 7 US communities, 2012–2013. JAMA 314:1479–1487. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grundmann H, Glasner C, Albiger B, Aanensen DM, Tomlinson CT, Andrasević AT, Cantón R, Carmeli Y, Friedrich AW, Giske CG, Glupczynski Y, Gniadkowski M, Livermore DM, Nordmann P, Poirel L, Rossolini GM, Seifert H, Vatopoulos A, Walsh T, Woodford N, Monnet DL, European Survey of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE) Working Group . 2017. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in the European survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE): a prospective, multinational study. Lancet Infect Dis 17:153–163. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang R, Chan EW, Zhou H, Chen S. 2017. Prevalence and genetic characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae strains in China. Lancet Infect Dis 17:256–257. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L, Todd R, Kiehlbauch J, Walters M, Kallen A. 2016. Notes from the field: pan-resistant New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae—Washoe County, Nevada, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2015. M100-S25 performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-fifth informational supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 12.bioMérieux 2012. Etest application guide. bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France: http://www.biomerieux-usa.com/clinical/etest. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi MJ, Ko KS. 2015. Loss of hypermucoviscosity and increased fitness cost in colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 23 strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6763–6773. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00952-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirel L, Jayol A, Bontron S, Villegas MV, Ozdamar M, Türkoglu S, Nordmann P. 2015. The mgrB gene as a key target for acquired resistance to colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:75–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin D, Lee EJ, Huang H, Groisman EA. 2006. A positive feedback loop promotes transcription surge that jump-starts Salmonella virulence circuit. Science 314:1607–1609. doi: 10.1126/science.1134930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Band VI, Crispell EK, Napier BA, Herrera CM, Tharp GK, Vavikolanu K, Pohl J, Read TD, Bosinger SE, Trent MS, Burd EM, Weiss DS. 2016. Antibiotic failure mediated by a resistant subpopulation in Enterobacter cloacae. Nat Microbiol 1:16053. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009. Class II special controls guidance document: antimicrobial susceptibility test (AST) systems. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Antibiograms of colistin-heteroresistant K. pneumoniae isolates. Results of MicroScan automated broth microdilution (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA) antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Mu9 and Mu156. MIC results are listed with the interpretive category (S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant) as defined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Antibiotics designated N/A have no defined CLSI MIC breakpoints for K. pneumoniae. Download TABLE S1, PDF file, 0.03 MB (34.7KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Beta-lactam resistance genes in K. pneumoniae isolates. PCR analysis was conducted on Mu9 and Mu156 for 9 common K. pneumoniae resistance genes. Positive genes were those that produced a band at the expected size as assayed by PCR. Download TABLE S2, PDF file, 0.02 MB (22.5KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

An increased broth microdilution incubation time facilitates the detection of colistin heteroresistance. (A, B) The colistin MIC was determined for heteroresistant K. pneumoniae by both broth microdilution (A) and Etest (B) at the recommended 24-h time point or after 48 h of incubation. The dashed line indicates the CLSI breakpoint for resistance to colistin at 4 µg/ml (11). n = 3. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.04 MB (37.4KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

The frequency of the resistant subpopulation increases in the presence of colistin. Heteroresistant K. pneumoniae cells were grown without colistin (pretreatment), subcultured with 100 µg/ml colistin (colistin treated), and then subcultured again without colistin (drug-free subculture). The frequency of the colistin-resistant subpopulation was measured at each step. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.03 MB (31KB, pdf) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.