ABSTRACT

Background:

Life review therapy, used as part of a comprehensive therapy plan for increasing the quality of life of the elderly, helps them to resolve their past conflicts, reconstruct their life stories, and accept their present conditions. The present study aimed to explore the effectiveness of life review therapy on the quality of life of the elderly.

Methods:

The present study was a randomized controlled trial with a pre-posttest design during April to Aug 2014. The study was conducted on 35 members of the elderly day care centers in Shiraz, Iran, that were randomly assigned to two groups (experimental and control). The subjects in the experimental group attended 8 two-hour sessions of life review therapy. The quality of life of the elderly participants was evaluated before, immediately, one month, and three months after the intervention using the quality of life questionnaire (WHOQOL_BREF). Data analysis was conducted through SPSS version 22, using statistical tests including Chi-square, repeated measures test and T-test, with the significance level of 0.05.

Results:

The results of the study showed that life review therapy interventions significantly improved the quality of life of the elderly (P<0.05). Moreover, group interaction with passage of time was also significant, which indicates that the pattern of changes has been different between the two groups.

Conclusion:

The findings of the study confirm the research hypotheses, showing that the application of life review is effective and viable. It is recommended that all nursing homes and even the families of the elderly should employ this convenient, inexpensive, quick, and practical method.

Trial Registration Number: IRCT2015021621106N1

KEYWORDS: Elderly, Life, Quality of life, Review

INTRODUCTION

Aging is an expected physiological process in which the physical and mental strength of a person decreases suddenly and without rebound. During this aging process, there are some physical, mental and social changes that affect the quality of life of the elderly.1

Old age is becoming increasingly important all over the world; the ever-increasing population of the elderly is one of the most challenging issues in the domains of health and welfare.1,2 The growth of the elderly population has been so important that it has come to be described as the “silent revolution”.3 It is predicted that by 2016 the number of ageing population in Iran will rapidly increase. Among the countries with fast-ageing populations, Iran ranks the third across the world,4 i.e. ageing is a major present and future challenge in Iran.5 Considering the needs and issues of individuals at this life stage is a social necessity. Though the quality of life of the elderly is a very important factor, it is often neglected.6

Over the past two decades, the quality of life has been an important subject in clinical trials.7 The increase in the indexes of life span and life expectancy has caused the researchers and experts to pay more attention to the subject of how to spend one’s old age, or the elderly people’s quality of life.8 Considering the great urgency of the issue, it is necessary that appropriate healthcare programs be developed and implemented for this age group. One of the approaches to improving the quality of life and well-being of the elderly is group life review sessions.

The concept of life review was first introduced by Butler in his 1963 article.9 Butler proposed that life review is a natural process which we all resort to when we are approaching the end of our lives. He defined life review as a natural event in which an individual recalls his/her past experiences, evaluates them, and analyzes them in order to achieve a more profound self-concept.10 In 1974, by presenting a framework for this developmental task, Butler made the life review more purposeful and suggested it as a form of therapy.11

In life therapy, an individual’s forgotten, but influential, experiences are revealed; their negative experiences are analyzed logically; and their positive experiences are discussed in order to make them feel useful and important again.12 Life review addresses the subjects which, due to unresolved conflicts, are hard for a person to analyze alone without feeling upset, disgusted, or guilty.10 The roots of life review lie in Erikson’s developmental theory, in which, at the eighth stage, an individual tries to achieve integrity.13,14 In view of the above-mentioned facts about the importance and effectiveness of psychological interventions regarding certain psychological aspects of the elderly, and the lack of any research on the effects of life review on the quality of life of the elderly, the present study aimed to explore the effectiveness of life review therapy on the quality of life of the elderly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was a randomized controlled trial with a pre-posttest design, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (CT-92-6616). This study was conducted on 35 elderly members of the elderly day care centers of Shiraz. The subjects who met the inclusion criteria were divided into control and experimental groups, and for the sessions the males and females were separated in each group. The intervention consisted of eight two-hour sessions of life review which were held twice weekly. The independent and dependent variables were, respectively, life review and the subjects’ quality of life scores.

The sample size was calculated as 22 in each group based on the data of a similar study 14 using Med.Calc statistical software (power: 80%, α: 0.05, loss rate: 20%, d: 5.3, Ϭ: 4.7 and 5.6) and considering the following formula.

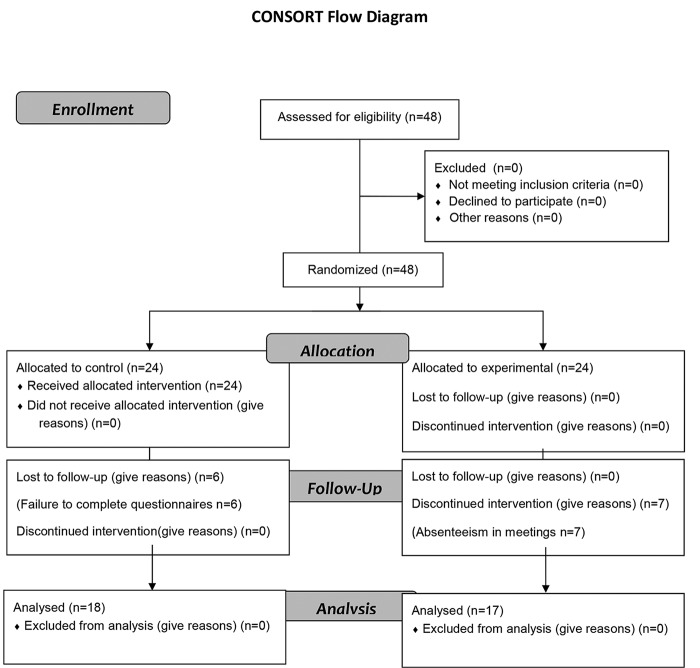

All the elderly members of the elderly day care centers of Jahandidegan and Soroush were the statistical population of the study. Those who had inclusion criteria entered the study (48 subjects). Based on a random number table, the subjects were randomly divided into the control and experimental groups. Finally, after attrition (Absenteeism in meetings n=7 and Failure to complete questionnaires n=6), the study was conducted on 35 subjects; 18 subjects were assigned to the control group and 17 to the experimental group. (figure 1)

Figure1.

CONSORT flowchart

The inclusion criteria were age between 60 and 78, ability to understand and speak Farsi, willingness to participate in the sessions, and conscious completion of the consent form. The exclusion criteria were attending similar educational classes, missing more than one session, and being unwilling to cooperate further for any reason. Having made a list of all the qualified subjects, the researchers explained the type and objectives of the study to the potential participants in a meeting before the intervention. The subjects who were willing to participate in the study and completed the written informed consent form were asked to complete the demographic questionnaire and a 26-item quality of life questionnaire.

The life review sessions were conducted by the researcher based on Haight and Webster’s life review therapy process:15 dealing with structure, evaluation, generality and individuality. Haight and Webster’s therapy model reviews an individual’s entire life cycle in 8 two-hour sessions which are held weekly. This form was developed by Haight in 1989 and is used for group therapies based on life review. The form consists of five separate parts and deals with important life events, such as an individual’s losses, major activities, descriptions and relationship with influential people and major developmental experiences, over childhood, adolescence, adulthood, middle-ages, and old age. The sessions included lectures, group discussions, and written assignments based on the questions raised in Haight and Webster’s model (Table 1). The control group continued their usual activities of life.

Table 1.

The Contents of the Sessions

| Session | Time | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 120 min | Introduction to the process and program rules, Familiar participants together and with therapists, create an agreement. |

| 2 | 120 min | Erickson’s Model in Childhood: the use of the life assessment form, efforts to increase trust in members. |

| 3 | 120 min | Erickson’s Model in young age: the use of form of life review, Increase member participation, Asking Questions and submit opinions. |

| 4 | 120 min | Erickson’s Model at home and family: the use of form of life review, Feedback support members. |

| 5 | 120 min | Erickson’s Model in adulthood: the use of form of life review, Criticism of the unique characteristic of life, A significant increase in the interaction of the group. |

| 6 | 120 min | Erickson’s Model (Perfection): by using of the life assessment form and counseling skills, Change the interactions in the group from leader to member to member form, Formation of group identity. |

| 7 | 120 min | Erickson’s Model (Coherence): by using of the life assessment form and counseling skills, check all items, sessions were spontaneously conducted by group members, re-evaluation of unresolved previous issues. |

| 8 | 120 min | Summarizing the provided content, completion of questionnaires. |

The data collection instruments in the present study consisted of two questionnaires: a demographic information questionnaire (age, gender, education, number of children, etc.), and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL_BREF) consisting of 26 five-point Likert scale questions. The WHOQOL-BREF is a shorter version of the original instrument (WHOQOL-100) that may be more convenient for use in large research studies or clinical trials. The latter investigates a person’s life in four health-related areas: physical well-being (7 items), psychological well-being (6 items), social relationships (3 items), and living environment (8 items). The first question is about the quality of life; the second one is a general question about health conditions; the next 24 questions evaluate the respondent’s quality of life in the four above-mentioned domains. Each item of the WHOQOL-BREF is scored from 1 to 5 on a response scale. Individual’s perception of the quality of life is measured by summing the total scores for each particular domain and overall quality of life (OQOL). The mean score of items within each domain is used to calculate the domain score. Initially, a raw score is obtained for each subscale, which must be converted to transformed scores through a formula. In this study, the overall quality of life score is calculated. All domain scores and OQOL are scaled in a positive direction (higher score indicate higher QOL). WHOQOL scale (questionnaire) is a highly valid instrument, and standardized in many countries. Cronbach alpha values for each of the four domain scores ranged from 0.66 (Social relationships) to 0.84 (Physical health), demonstrating good internal consistency. The test-retest reliabilities for the domains were 0.66 for physical health, 0.72 for psychological aspects, 0.76 for social relationships and 0.87 for environment.16 The questionnaire has been translated into over 40 languages, including Persian and was standardized and validated in Iran with a sample of over 30 years of age (5892 samples). For the total sample, the internal consistency of the domains was satisfactory to good, yielding Cronbach’s Alpha ranging from 0.78 for psychological health to 0.82 for social relationships; its reliability was confirmed with a Chronbac’s alpha of 0.86.17

Data collection in phase two (immediately after the intervention), phase three (one month after the intervention), and phase four (three months after the intervention) was performed after the subjects completed the quality of life questionnaire. Subsequently, the collected data were analyzed. To establish the blindness of the study, the questionnaires before the intervention was checked by a research assistant and data were analyzed by another researcher.

Data analysis was conducted through SPSS version 22, using statistical tests including Chi-square, repeated measures and t-test, with the significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

The present study was conducted on 35 members of the retirement centers of Shiraz, all of whom were aged between 60 and 78 years. In terms of gender distribution, 17 elderly participants were male and 18 were female. 82.4 percent and 66.7 percent of the participants in the experimental group and the control group were married, respectively. With regard to education, the majority of the subjects in the experimental group were high-school or college graduates 12 (70.6). The results of the Chi-square test showed that there were no significant differences between the distributions of the subjects in the control group and experimental group in age, gender, education, and marital status, and the two groups were homogeneous in terms of the above-mentioned variables (P>0.05). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic characteristics in the experimental and control groups

| Demographic Variable | Group | experimental group N=17 | Control group N=18 | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Age( year) | 60-66 | 6 (35.3) | 8 (44.4) | 0.45 |

| 67-72 | 10 (58.8) | 7 (38.9) | ||

| 73-78 | 1 (5.9) | 3 (16.7) | ||

| Gender | Male | 8 (47.1) | 9 (50) | 0.86 |

| Female | 9 (52.9) | 9 (50) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 3 (17.6) | 6 (33.3) | 0.44 |

| Married | 14 (82.4) | 12 (66.7) | ||

| Educational level | Illiterate | 1 (5.9) | 3 (16.7) | 0.27 |

| Primary education | 4 (23.5) | 2 (11.1) | ||

| Diploma | 7 (41.2) | 6 (33.3) | ||

| Higher education | 5 (29.4) | 7 (38.9) |

Chi-square test

In Table 3, p-values below 0.05 indicated a difference between the two phases of the quality of life. In the case of the control group, the time-group comparison showed that the results were significant after three months; however, the results were significance and decreased. As to the experimental group, the results were significant and increased, meaning that with the passage of time, the quality of life of the elderly participants increased.

Table 3.

Pairwise comparison of the control and experimental group’s quality of life at different phases

| Group | Quality of life | Mean difference | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Before | Immediately After | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| One months later | 0.06 | 0.17 | ||

| Three months later | 0.18 | 0.01 | ||

| Immediately after | One months later | 0.02 | 0.56 | |

| Three months later | 0.14 | 0.01 | ||

| One months later | Three months later | 0.12 | 0.03 | |

| Experimental | Before | Immediately After | -0.08 | 0.02 |

| One months later | -0.48 | 0.001 | ||

| Three months later | -0.67 | 0.001 | ||

| Immediately after | One months later | -0.40 | 0.001 | |

| Three months later | -0.59 | 0.001 | ||

| One months later | Three months later | 0.18 | 0.001 | |

Dependent t-test

In order to analyze the pattern of changes in the quality of life scores of the participants in the two experimental groups and the two control groups, the researchers used the repeated measures test and independent t-test. Based on the findings of the study, there was a statistically significant difference between the means of the quality of life scores as measured at the four evaluation phases, which proved the positive impact of the intervention on the quality of life of the subjects in the experimental group. Moreover, the results showed that the effect of time was significant, too (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the mean ±SD of quality of life scores at different times (before, immediately, one month, and three months after the intervention) in the experimental and control groups

| Group | Time | Before intervention Mean±SD | immediately after Mean±SD | 1 months after Mean±SD | 3 months after Mean±SD | P value** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Group | Time/group | ||||||

| Experimental group | 2.96±0.48 | 3.04±0.43 | 3.45±0.46 | 3.64±0.40 | 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.001 | |

| Control group | 3.17±0.44 | 3.13±0.40 | 3.11±0.30 | 2.99±0.28 | ||||

| P value* | 0.19 | 0.53 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | ||||

Independent t-test;

Repeated measures test

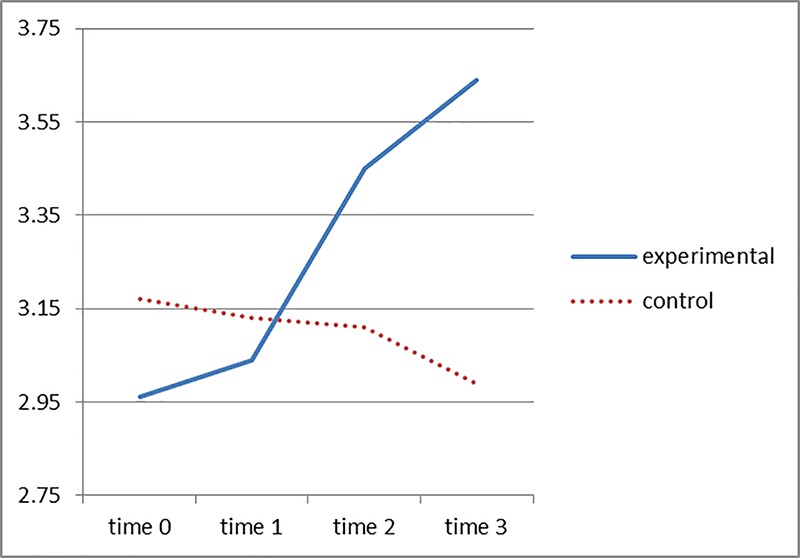

The results of Table 4 show that the trend of changes in the quality of life was significant (P<0.05). In other words, there is a statistically significant difference among the quality of life scores as measured at the four phases. Moreover, the time group interaction was also significant, which indicates that the pattern of changes has been different between the two groups. Too t-test results showed that the differences between the two groups in terms of quality of life were significant only at phases 3 and 4 (P<0.05). (Table 4)

As figure 2 shows, the means of the quality of life scores of the subjects in the experimental group had an upward trend, while in case of the control group, the trend was decreased. Since the time group interaction with passage of time was significant, the patterns of the changes must be analyzed separately for each group. Based on the findings of the study, there were no significant differences between the means of the quality of life scores in the control and experimental groups at 1 phase. (P=0.19)

Figure2.

The trend means of quality of life scores at different times in the experimental and control groups

The results of Table 5 show that the trend of changes in the quality of life of both groups was significant (P<0.001). In other words, there was a significant difference between the two groups’ quality of life results as obtained from the four evaluation phases.

Table 5.

A time-based comparison of the groups’ quality of life scores

| Source | The sum of squares | D f | Average of squares | F | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time changes in quality of life(control) | 0.33 | 1.85 | 0.18 | 5.49 | 0.01 |

| Error | 1.03 | 31.60 | 0.03 | ||

| Time changes in quality of life(experimental) | 5.31 | 1.54 | 3.43 | 61.63 | 0.001 |

| Error | 1.38 | 24.77 | 0.05 |

Repeated measures test

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to explore the effects of life review interventions on the quality of life of the elderly. The comparison of the changes in the means of the experimental group’s quality of life scores as obtained immediately, one month, and three months after the intervention proved the effectiveness of the intervention. The results of this study showed that the eight life review sessions had a positive impact on the quality of life of the elderly subjects. The literature review shows that there are no other studies similar to the present one; however, the results of the present study are in agreement with the findings of other studies that have investigated the effectiveness of life review therapy.18-20

The aim of science today is to develop proper programs for the elderly to improve their quality of life and make them equal with the rest of the society. The life review therapy is more efficient than the conventional clinical therapies. They are well acquainted with the content of their own lives and do not need to be taught any new skills.13 Comparing the effectiveness of reminiscence group therapy with other forms of group therapy, Veis (1993) discovered the former to be supeior.21

In the previous study, the researcher concluded that six-session spiritaually-oriented life review therapy improved the patients’ quality of life.22 Similarly, studying the effects of an eight-session life review group theray on 40 elderly patients with chronic pain, the researcher (2012) reported a considerable decrease in the patients’ pain and an increase in their quality of life.23 He states that in life review a counselor should create situations in which the elderly counselee can come up with new and better structured meanings for his/her past and present experiences and eventually reaches a positive picture of his/her life, which is consistent with the results of the present stduy.23

The two Iranian studies mentioned above were both conducted to examine the effects of life review on patients; the subjects of the present study, however, were not patients. Given the cultural and developmental differences between men and women, the researchers in the present study had the male and female participants attend separate classes. As with many other studies that prove the effectiveness of life review, the present study shows that life review can positively affect the quality of life of the elderly over time. For the first time in research on life review therapy, this study used the 26-item quality of life questionniare; the results show that as time passes, life review produces better results and positively affects the quality of life of the elderly. Yet, it should be noted that in two separate studies, Michiyo Ando et al. have studied the short-term effect of life review on the spiritual well-being and depresion of bereaved families and patients with terminal cancer and reported positive results.19,24 In a complicated subject with many different aspects, quality of life cannot be improved by short-term programs; yet, because of their special conditions, bereaved families and terminal patients can benefit from the effects of life review in the short run. The difference between the conditions of the subjects and objectives of the studies can explain the difference between the results.

One resaon for the significance of the results can be the effectiveness of life review therapy as mentioned; dedicating enough time to the process, considering an individuals’ entire life from birth to the present, and analyzing and integrating the memories of the subjects can be influential factors.

The results of the present study are in agreement with previous studies on the effects of life review on patients with PTSD,25 reporting that the effectiveness of life review is equal to other cognitive therapies.18 It can be concluded that life review therapy is in agreement with the processes of cognitive therapies, and reconstructing the counselees’ negative experiences is one of the responsibilities of the counselors in life review. Life review will be effective if it can help a patient recollect his/her positive and negative experiences and evaluate his/her life in a balanced manner.

In a previous study, the researchers26 report that life review positively affects the quality of life of the elderly; the results of their study show that group life review therapy can play an important role in increasing the quality of life of the elderly in the medium and long term. According to their study, the mean of the subjects’ quality of life scores increased one month and three months after the life therapy intervention. In life review therapy, an individual shares his/her memories with others, which increases social interactions and on’e sense of social value.

The results of the present study are also consistent with the previous studies,13,27-29 all of which confirm the positive impact of life review therapy or reminiscence therapy on different aspects of the life of the elderly; the results also verify the Butler’s first theory indicating that life review is a modified cognitive therapy.10

Due to the difficulty of conducting research on the elderly, the researchers in the present study used convenience sampling, which is one of the limitations of the study. Moreover, the study was limited to the members of the retirement centers, which limits the transferability of the results to other elderly groups.

The present study was conducted to provide preliminary proof of the effectiveness of life review; thus, there is a need for further research to verify the results of the present work and determine the stability of the results of this kind of intervention. To increase the accuracy of the research plans in future studies, it is suggested that researchers should compare the results of the current study with other existing programs.

CONCLUSION

The results showed that the eight-session life review program improved the subjects’ quality of life. According to the results of this study, clinical experts can use this therapeutic program to increase various components of psychology for the elderly, and nurses can use this effective and efficient way to provide care services, even in the area of prevention and adaptation. According to the experimental evidence of the positive effects of life review, it is recommended that all nursing homes and even the families of the elderly should employ this convenient, inexpensive, quick, and practical method.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The present study was extracted from Afsar Amirsadat’s M.Sc. thesis at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Grant No: 926616). The researchers’ thanks are due to the authorities of the university and the members of the elderly day care centers in Shiraz. The authors would like to thank the research deputy at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for financial assistance and also Center for Development of Clinical Research of Nemazee Hospital and Dr. Nasrin Shokrpour for editorial assistance.

Conflict of Interest:None declared.

REFRENCES

- 1.Senol V, Unalan D, Soyuer F, Argun M. The Relationship between Health Promoting Behaviors and Quality of Life in Nursing Home Residents in Kayseri. Journal of Geriatrics. 2014;2014:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadegh Moghadam L, Foroughan M, Mohammadi F, et al. Aging Perception in Older Adults. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2016;10:202–9. [In persian] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hesamzadeh A, Maddah SB, Mohammadi F, et al. Comparison of Elderlys” Quality of Life” Living at Homes and in Private or Public Nursing Homes. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2010;4:66–74. [In persian] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garousi S, Safizadeh H, Samadian F. The Study of Relationship between Social Support and Quality of Life among Elderly People in Kerman. Jundishapur Scientific Medical Journal. 2012;11:303–15. [In persian] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovell M. Caring for the elderly: changing perceptions and attitudes. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 2006;24:22–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee TW, Ko IS, Lee KJ. Health promotion behaviors and quality of life among community-dwelling elderly in Korea: a cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006;43:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuda S, Okamoto F, Yuasa M, et al. Vision-related quality of life and visual function in patients undergoing vitrectomy, gas tamponade and cataract surgery for macular hole. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009;93:1595–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.155440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kathleen MH, Getchell N. Life span motor development. 5th ed. Canada (USA): Human Kinetics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mastel-Smith BA, McFarlane J, Sierpina M, et al. Improving depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults: a psychosocial intervention using life review and writing. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2007;33:13–9. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20070501-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler RN. Life review: an interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 1963;26:65–76. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler RN. Succesful aging and the role of the life review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1974;22:529–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1974.tb04823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kazemian S. The effect of life review on the rate of anxiety in adolescent girls of the divorced families. Knowledge & Research in Applied Psychology. 2012;1:11–7. [In persian] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watt LM, Cappeliez P. Integrative and instrumental reminiscence therapies for depression in older adults: Intervention strategies and treatment effectiveness. Aging & Mental Health. 2000;4:166–77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haight BK, Gibson F, Michel Y. The Northern Ireland life review/life storybook project for people with dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2006;2:56–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingebretsen R. The Art and Science of Reminiscing: Theory, Research, Methods and Application. Ageing and Society. 1995;15:578–80. [Google Scholar]

- 16. The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Usefy AR, Ghassemi GR, Sarrafzadegan N, et al. Psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF in an Iranian adult sample. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;46:139–47. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haight B, Michel Y, Hendrix S. The extended effects of the life review in nursing home residents. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2000;50:151–68. doi: 10.2190/QU66-E8UV-NYMR-Y99E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ando M, Morita T, Okamoto T, Ninosaka Y. One-week Short-Term Life Review interview can improve spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2008;17:885–90. doi: 10.1002/pon.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haber D. Life review: implementation, theory, research and therapy. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2006;63:153–71. doi: 10.2190/DA9G-RHK5-N9JP-T6CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss JC. A comparison of cognitive group therapy to life review group therapy with older adults [thesis] Virginia (USA): University of Virginia; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taghaddosy M, Fahimifar A. Effect of life review therapy with spiritual approach on the life quality among cancer patients. FEYZ Journal. 2014;18:135–44. [In persian] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alizadehfard S. The effect of life review group therapy on elderly with chronic pain. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2012;7:60–7. [In persian] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, et al. Efficacy of short-term life-review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esmaeili M. Study the effectivness of life review therapy with emphasis on Islamic ontology on decreasing the symptoms PTSD. Culture Counseling. 2010;1:1–20. [In persian] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanaoka H, Okamura H. Study on effects of life review activities on the quality of life of the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2004;73:302–11. doi: 10.1159/000078847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frazer CJ, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. Effectiveness of treatments for depression in older people. Med J Aust. 2005;182:627–32. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson LA. A comparison of the effects of reminiscence therapy and transmissive reminiscence therapy on levels of depression in nursing home residents. Minnesota (USA): Capella University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharif F, Mansouri A, Jahanbin I, Zare N. Effect of group reminiscence therapy on depression in older adults attending a day center in Shiraz, southern Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:765–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]