Abstract

Toll receptors are involved in innate immunity of invertebrates. In this study, we identify and characterize two Toll genes (named HcToll4 and HcToll5) from triangle sail mussel Hyriopsis cumingii. HcToll4 has complete cDNA sequence of 3,162 bp and encodes a protein of 909 amino acids. HcToll5 cDNA is 4,501 bp in length and encodes a protein of 924 amino acids. Both deduced HcToll4 and HcToll5 protein contain signal peptide, extracellular leucine rich repeats (LRRs), and intracellular Toll/interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor domains. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis revealed that HcToll4 and HcToll5 were largely distributed in the hepatopancreas and could be detected in the gills and mantle. HcToll4 and HcToll5 expression could respond to Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) or Poly I:C challenge. RNA interference by siRNA results showed that HcToll4 and HcToll5 were involved in the regulation of theromacin (HcThe) and whey acidic protein (HcWAP) expression. Based on these results, HcToll4 and HcToll5 might play pivotal function in H. cumingii innate immune response.

Keywords: Hyriopsis cumingii, toll receptors, RNAi, innate immunity, anti-microbial peptides

Introduction

Innate immune system is the first line of host defense against inevitably encounter pathogens and is conserved throughout evolution. The activation of innate immune response requires the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by pathogen-recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Tolls/Toll-like receptors (TLRs), Nod-like receptors (NLRs), and RIG-like receptors (RLRs) (Bilak et al., 2003; Carty and Bowie, 2010). These PRRs can recognize the unique patterns of PAMPs as conserved molecular motifs on the surface of invading microbes (Imler and Zheng, 2004; Kawai and Akira, 2010) and subsequently trigger a series of rapid and effective immune responses, including the release of molecules and circulating humoral and cellular components (Medzhitov, 2007).

In Drosophila melanogaster, Toll pathways are the major regulators of the humoral and cellular immune responses, which control the expression of genes regulated by microbial infection (Hoffmann and Reichhart, 2002; Valanne et al., 2011). Gram-positive bacteria, fungi, or certain viruses activate the Toll pathway, thus leading to the systemic production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that kill infective pathogens in D. melanogaster (Beutler, 2009; Hetru and Hoffmann, 2009). The key components of the Toll pathway in Drosophila include the cytokine-like ligand Spätzle, receptor Toll, intracellular adaptor myeloid-differentiation-factor-88 (MyD88), adaptor protein Tube, protein kinase Pelle, and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)-family transcription factors such as Dorsal and Dorsal-related immunity factor (Dif). After Toll pathway activation, Dorsal or Dif translocates into the nucleus, leading to the expression of several AMP genes (Belvin and Anderson, 1996; Lemaitre and Hoffmann, 2007; Valanne et al., 2011).

In vertebrates, TLRs directly recognize and bind the PAMPs of multifarious pathogens and act as a bridge between the innate and adaptive immunity (Akira et al., 2001). Vertebrate TLRs have extracellular leucine rich repeat (LRR) domains that mediate the recognition of PAMPs; transmembrane and intracellular Toll/interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor (TIR) domains are required for downstream signal transduction (Bowie and O'Neill, 2000; Kawai and Akira, 2010). Since the identification of the first Toll protein in D. melanogaster (Belvin and Anderson, 1996), Tolls or TLRs have been identified in many vertebrates and invertebrates. Approximately 10 and 12 functional TLRs have been characterized in humans and mice, respectively; among these, TLR1–TLR9 are conserved in both species (Kawai and Akira, 2010). Approximately 222 and 72 TLR-related genes existed in sea urchin and amphioxus genomes, respectively (Satake and Sekiguchi, 2012). Seventeen different kinds of TLRs have also been found in fish (Palti, 2011), and 16 TLRs have been described in lamprey genome (Armant and Fenton, 2002). In mollusks, Toll genes have been isolated in some mussels, including Zhikong scallop Chlamys farreri (Qiu et al., 2007), mollusk oyster Crassostrea gigas (Zhang et al., 2011), noble scallop Chlamys nobilis (Lu et al., 2016), triangle-shell pearl mussel Hyriopsis cumingii (Ren et al., 2014), and mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis (Toubiana et al., 2013). Mollusca Toll receptors have an extensive and constitutive tissue-level expression and are closely involved in innate immune responses against pathogenic infection (e.g., bacteria, virus; Qiu et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2011; Toubiana et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2016).

This study aims to (1) identify new Toll genes in H. cumingii, (2) clone their complete nucleotide sequences, (3) investigate their phylogenic relationships, (4) measure their constitutive tissue-specific expression, (5) quantify their expression level following in vivo challenges with bacteria or virus, and (6) investigate their involvement in innate immune response by exploring their possible relationship with downstream immune related genes.

Materials and methods

Triangle-shell pearl mussels and immune challenge

Two hundred H. cumingii specimens (15 g mean weight) were obtained from Wuhu City, Anhui Province, China and were cultured in oxygenated freshwater at 25°C. Different tissues, including hemocytes, hepatopancreas, gills, and mantle from five normal mussels were collected, pooled, and then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until total RNA extraction. In the experimental groups, approximately 100 μl of Staphylococcus aureus (3 × 107 cells), Vibrio parahaemolyticus (3 × 107 cells), White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) (105 copies/ml), or polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid poly I:C (0.5 μg/μl) were injected into the adductor muscles of H. cumingii (each group contained 20 mussels) using a 1 ml syringe. The hepatopancreas and gills of five mussels were collected after 2, 6, 12, and 24 h for RNA isolation.

Molecular cloning and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from various samples using RNApure High-purity Total RNA Rapid Extraction Kit (Spin-column; Bioteke, Beijing, China). Two expressed sequence tag sequences similar to the Toll genes were identified after analyzing the transcriptome data of the hepatopancreas from H. cumingii (data unpublished) and were used to clone the full length of Toll cDNAs by Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) method using gene-specific primers (Table 1). The 5′- and 3′-RACE were performed on RNA extracted from hepatopancreas using the Clontech SMARTer™ RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Takara, Dalian, China) and an Advantage 2 cDNA Polymerase Mix (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR products were ligated into the pEASY-T3 vector (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), transformed into competent Escherichia coli DH5α cells, plated onto LB–agar Petri dishes, and incubated overnight at 37°C. Positive clones containing the insert with the expected size were identified by colony PCR, and the selected clones were sequenced.

Table 1.

Sequences of the primers used in the study.

| Primers name | Sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| HcToll4-F | CCATTCTCAATCACAAGCGAGGCACAG |

| HcToll4-R | ACAACCGTCTTTCTGCTGCGATGGATG |

| HcToll5-F | ATCGGTGTAGCAGCAACTCAACCTCAT |

| HcToll5-R | TGACGAAAACTGTCCCTCCTTTGCTTG |

| UPM | |

| Long | CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT |

| Short | CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC |

| 5′-CDS Primer A | T25VN |

| SMARTer II A oligo | AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACXXXXX |

| 3′-CDS primer A | AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTAC(T)30VN |

| HcToll4-RT-F | ATGGAAAGGACGAGAACA |

| HcToll4-RT-R | GGGTGGGACAATAATAGGA |

| HcToll5-RT-F | TCGTCAAGTCATAGAGCAGA |

| HcToll5-RT-R | GAAAGGAGAAACCAACAGAA |

| HcWAP-RT-F | TGTAATGTTGACGGGAGTG |

| HcWAP-RT-R | CTGTTTTGTTTTGATGGCT |

| HcThe-RT-F | CACAGTTGGTGGTTCAGTAA |

| HcThe-RT-R | CGAATCCTTCAGTAGATGGT |

| Hcactin-RT-F | GTGGCTACTCCTTCACAACC |

| Hcactin-RT-R | GAAGCTAGGCTGGAACAAGG |

X = undisclosed base in the proprietary SMARTer oligo sequence. N = A, C, G, or T; V = A, G, or C.

Bioinformatics analysis

cDNA and amino acid sequence similarity searches were performed using BLAST algorithm (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Protein prediction was performed using software at the ExPASy (http://web.expasy.org/). Signal peptide and domain organization were predicted with SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). The calculated molecular weight and predicted isoelectric point were determined by ExPASy (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/). Protein multiple alignment analyses were performed using MEGA 5.05 and GENDOC software. The phylogenetic relationship of HcToll4 and HcToll5 was analyzed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with the MEGA 5.05 program and bootstrapping of 1,000 replicates.

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the aforementioned samples. A total of 500 ng RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed with PrimeScript® First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Dalian, China) with the Oligo-d(T) Primer according to the protocol of the manufacturer. The synthesized cDNA samples were stored at −20°C prior to use in qRT-PCR assays. Primers were designed using the Primer Premier 5 software and are listed in Table 1. Melting curve was analyzed to select the optimum primer pairs. qRT-PCR was performed in a 10.0 μl of reaction mix containing 1.0 μl of cDNA sample, 5.0 μl of 2 × SYBR® Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara, Dalian, China), 0.2 μl of each primer (10 μM), and 3.6 μl of nuclease-free water. The qRT-PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 30 s. Finally, melting curve analysis was conducted. The expression of β-actin in tissues and cells is relatively constant, and it is highly conserved among different species, so it was adopted as a housekeeping gene for internal standardization. A negative control without any cDNA template was included in the qRT-PCR analysis. The sequences of HcToll4 and HcToll5 specific primers and β-actin primers used in qRT-PCR are shown in Table 1. All samples were analyzed in triplicate during the qRT-PCR analysis. The expression level of HcToll4 or HcToll5 in different tissues was calculated using the comparative CT method, in which the discrepancy (ΔCT) between the CT of the HcToll4 or HcToll5 and β-actin was firstly calculated. Then the expression level of HcToll4 or HcToll5 was calculated by 2−ΔCT. The relative expression levels after immune challenge were calculated using 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Data from the qRT-PCR experiments were expressed as the means ± SE.

Synthesis of siRNAs, RNAi assay, and detection of mRNA

Based on the sequences of HcToll4 and HcToll5, small interfering RNA (siRNA) was synthesized in vitro with a commercial kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Takara, Japan). The siRNAs used were HcToll4-siRNA (5′-GGUGGAGACUGAAGGACUU-3′), HcToll5-siRNA (5′-GCAAGAAGCUCGGAUGCAA-3′), and the sequence of siRNA was scrambled to generate the control HcToll4-siRNA-scrambled (5′-UGAGGGAAGCUGUAGCUGA-3′), HcToll5-siRNA-scrambled (5′-GACAUGAGAGCCGACAUAG−3′).

The RNA interference (RNAi) assay was conducted in mussels by injecting siRNA (40 μg) into each mussel using a 1 ml sterile syringe. In brief, 20 μg of siRNA and V. parahaemolyticus (3 × 107 cells) were co-injected into the mussel at a volume of 100 μl per mussel. At 16 h after the co-injection, 20 μg of siRNA (100 μl/mussel) was injected into the same mussel. Simultaneously, the siRNAs-scrambled (20 μg; 100 μl/mussel) and V. parahaemolyticus (3 × 107 cells) were co-injected into the mussel. At 16 h after the co-injection, the siRNAs-scrambled (20 μg; 100 μl/mussel) were injected into the same mussel. V. parahaemolyticus (3 × 107 cells; 100 μl/mussel) alone was included in the injections as a positive control.

After RNAi treatment, the expression of downstream immune effector genes, theromacin (HcThe) and whey acidic protein (HcWAP) were detected by qRT-PCR with gene specific primers (Table 1). Hcactin was amplified as the control in the qRT-PCR assay. The assays were biologically repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

The numerical data collected from three independent experiments were processed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Student's t-test was employed to test significant differences.

Results

Cloning of HcToll4 and HcToll5

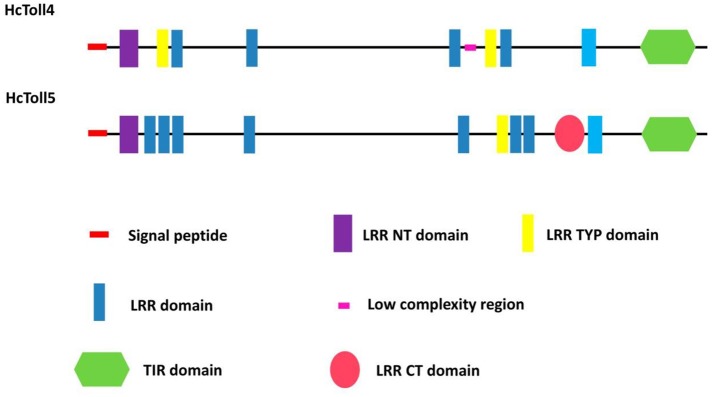

A 3,162 bp nucleotide sequence representing the complete cDNA sequence of HcToll4 (MG763893) was obtained (Figure S1A). The cDNA included a 111 bp 5′ untranslated region (UTR), a 3′ UTR of 321 bp with a poly (A) tail, and an open reading frame (ORF) of 2,730 bp. The ORF encoded a protein consisting of 909 amino acid residues with a predicted molecular weight of 104 kDa and a theoretical isoelectric point of 6.29. SMART analysis shows that HcToll4 contains a 17 amino acid (aa) signal peptide, a 37 aa Leucine rich repeat N-terminal (LRR_NT) domain, 2 24 aa LRRs, typical (most populated) subfamily (LRR_TYP) domains, 4 LRRs with aa length of 24–28, and a 141 aa intracellular Toll/interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor (TIR) domain (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Domain organization of HcToll4 and HcToll5 from mussel.

The full length HcToll5 (MG763892) cDNA contains 4,501 nucleotides, including an 138 bp 5′UTR, a 2,775 bp ORF that encodes a 924 amino acid protein, and a 1,588 bp 3′ UTR with a poly (A) tail (Figure S1B). Similar to HcToll4 domain organization, HcToll5 contains a 18 aa signal peptide, a 37 aa LRR_NT domain, 7 LRR domains with aa length of 23–28, a 24 aa LRR_TYP domain, a Leucine rich repeat C-terminal (LRR_CT) domain of 57 aa, and a 139 aa TIR domain (Figure 1). The predicted HcToll5 protein has a molecular mass of 105.6 kDa and an isoelectric point of 6.12.

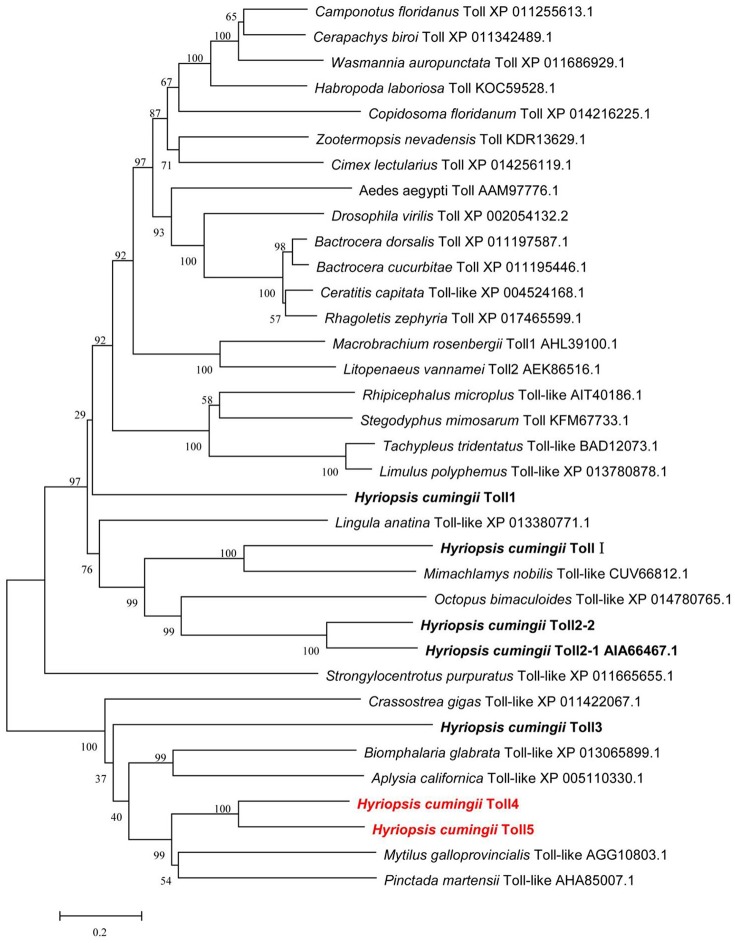

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple amino acid sequence alignments showed that HcToll4 and HcToll5 were highly conserved with each other, especially in the TIR motif (Figure S2). BLASTX result showed that HcToll4 was 35% identical with Toll-like receptor from M. galloprovincialis, 33% with Toll-like receptor 4 from Pinctada martensii, 32% with Toll-like receptor 4 from C. gigas, and 30% with Toll-like receptor 4 from Biomphalaria glabrata. HcToll5 shared 34% identity with C. gigas Toll-like receptor 2, 33% identity with M. galloprovincialis Toll-like receptor, 30% with P. martensii Toll-like receptor 4 and Aplysia californica Toll-like receptor 3. The phylogenetic tree based on amino acid sequences from multiple Toll families was constructed by the NJ method with the assistance of MEGA software 5.05 (Figure 2). HcToll4 and HcToll5 were clustered with other bivalve Toll family members from M. galloprovincialis and P. martensii and then grouped with gastropoda Tolls from B. glabrata and A. californica.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of HcToll4 and HcToll5 with other Toll receptors or TLRs. Phylogenetic tree was conducted with MEGA 5.05 using NJ method, and the reliability of the branching was tested by bootstrap resampling (1,000 pseudo-replicates).

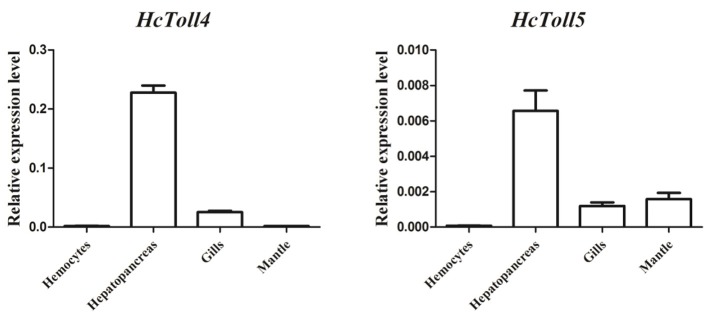

Tissue distributions of HcToll4 and HcToll5 mRNAs

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of various tissues including hemocytes, hepatopancreas, gills, and mantle showed the expression levels of HcToll4 and HcToll5 in H. cumingii (Figure 3). The highest HcToll4 transcript was observed in hepatopancreas, followed by in gills, but was absent in hemocytes and mantles. HcToll5 is largely distributed in hepatopancreas as compared in mantles and gills.

Figure 3.

qRT-PCR analysis of HcToll4 and HcToll5 in the hemocytes, hepatopancreas, gills, and mantle of H. cumingii.

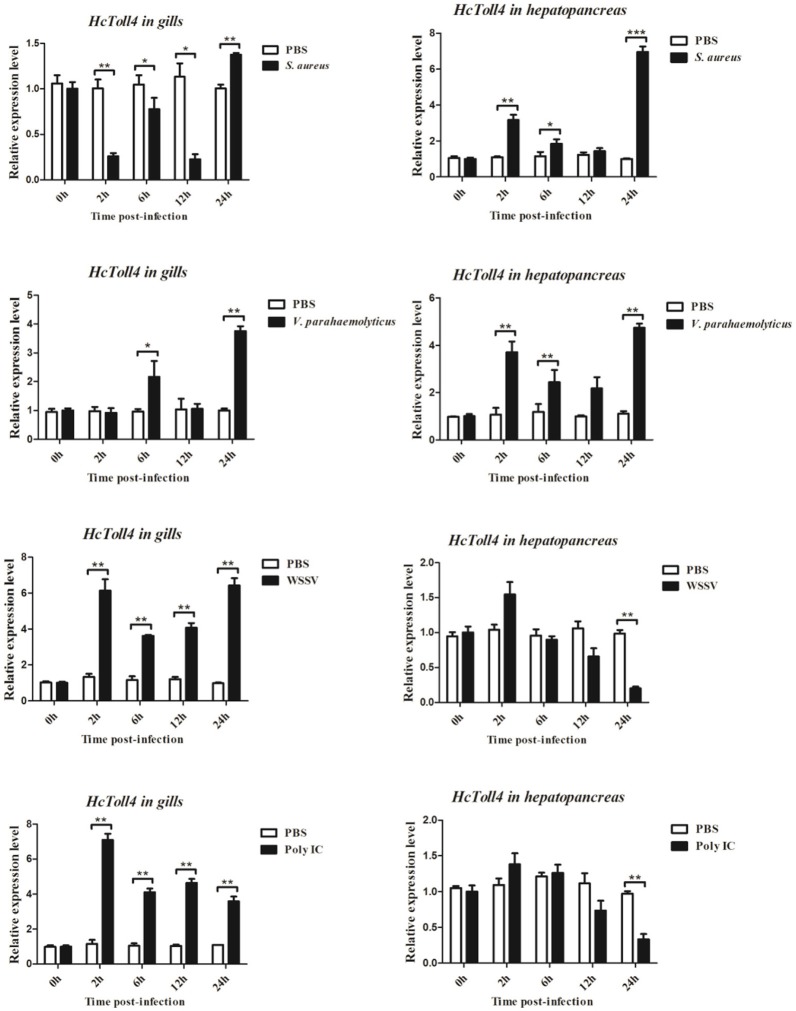

Transcriptional regulation of HcToll4 after immune challenge

The expression patterns of HcToll4 in gills and hepatopancreas under conditions of S. aureus, V. parahaemolyticus, WSSV or poly I:C challenge were observed using qRT-PCR to investigate the roles of HcToll4 on the anti-bacterial and anti-virus innate immunity of H. cumingii (Figure 4). After S. aureus stimulation, the mRNA expression level of HcToll4 in gills was down-regulated at 2–12 h and then up-regulated at 24 h compared with that in the PBS control group, HcToll4 in hepatopancreas was up-regulated at 2 h, slowly down-regulated from 6 to 12 h, and finally increased to the highest level at 24 h. After challenge with V. parahaemolyticus, HcToll4 expression in gills was increased at 6 and 24 h, whereas that in hepatopancreas was significantly up-regulated at 2 and 24 h. After a significant increase at 2 h post WSSV stimulation, the mRNA expression of HcToll4 in gills decreased at 6 h and then gradually increased from 12 to 24 h, whereas that in hepatopancreas was also increased at 2 h and then decreased from 6 to 24 h as compared with that in the PBS group. In poly I:C stimulated group, HcToll4 in gills was quickly increased at 2 h and then slowly down-regulated from 6 to 24 h, whereas that in hepatopancreas showed no significant changes from 2 to 12 h and was down-regulated at 24 h.

Figure 4.

Analysis of HcToll4 expressions in the gills and hepatopancreas from the mussels challenged with S. aureus, V. parahaemolyticus, WSSV, or Poly I:C using qRT-PCR methods. β-actin was used as a reference gene for internal standardization. Each bar represents the value from three independent PCR amplifications and quantifications. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) compared with that of the control.

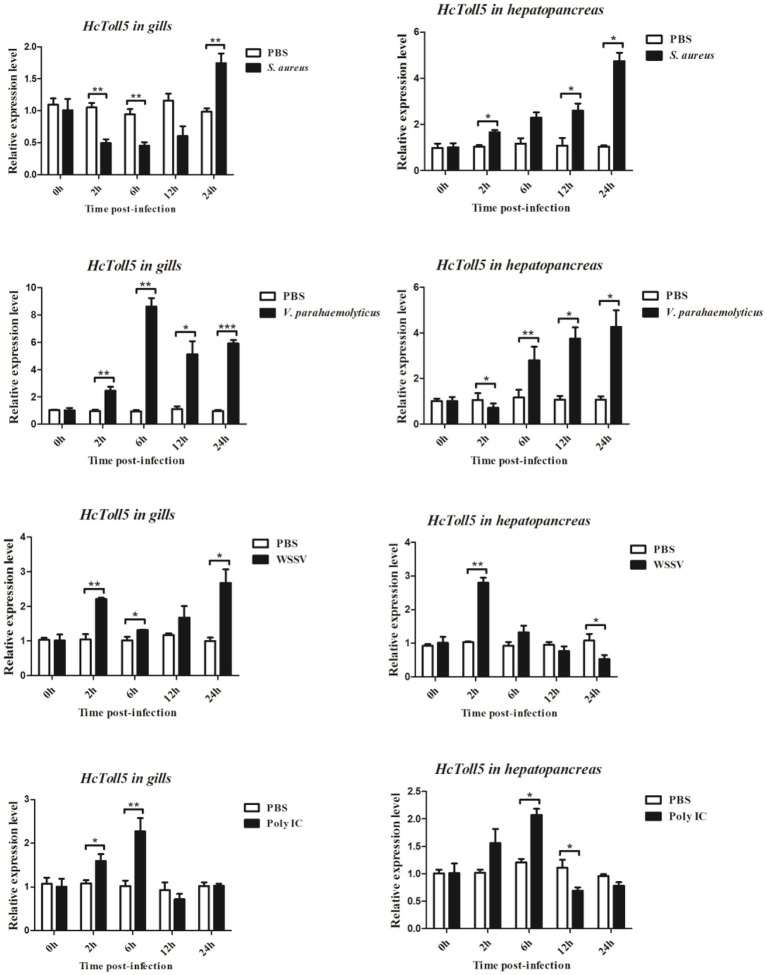

Time-course expression profiles of HcToll5 after immune challenge

The mRNA expression levels of HcToll5 in gills and hepatopancreas were investigated from 2 to 24 h after four immune challenges (Figure 5). After S. aureus challenge, HcToll5 mRNA in gills dropped to a low level from 2 to 12 h, then increased to its highest level at 24 h, whereas that in hepatopancreas was continuously up-regulated from 2 to 24 h. HcToll5 expression levels in gills increased to the highest level by 6 h after V. parahaemolyticus challenge and then slowly decreased from 12 to 24 h; whereas that in hepatopancreas began to decrease within 2 h, increased from 6 to 24 h, and reached maximum at 24 h. In WSSV stimulated group, HcToll5 mRNA in gills was increased at 2 h, and its expression level reached a second peak at 24 h; whereas that in hepatopancreas was significantly up-regulated at 2 h and then gradually decreased to the lowest level from 6 to 24 h. After poly I:C challenge, HcToll5 expression quickly increased to the highest level at 6 h both in gills and hepatopancreas and then decreased from 12 to 24 h to the control level.

Figure 5.

Analysis of HcToll5 expressions in the gills and hepatopancreas from the mussels challenged with S. aureus, V. parahaemolyticus, WSSV, or Poly I:C using qRT-PCR methods. β-actin was used as a reference gene for internal standardization. Each bar represents the value from three independent PCR amplifications and quantifications. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) compared with that of the control.

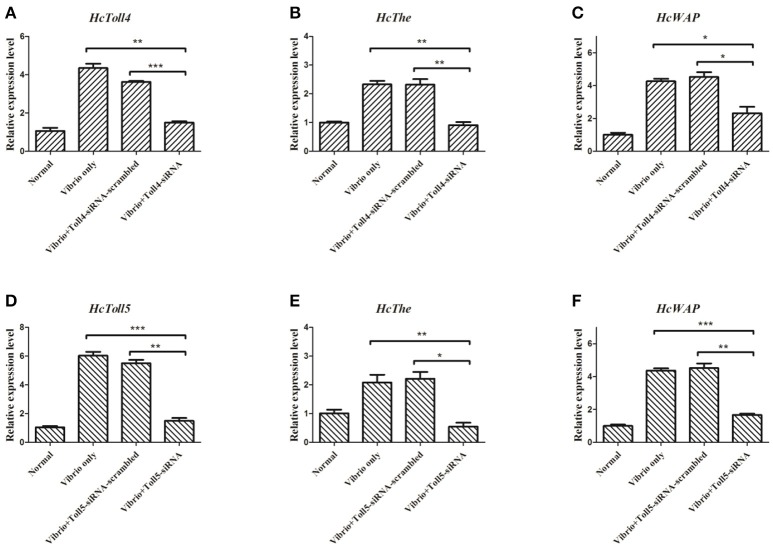

RNAi of HcToll4 or HcToll5 suppressed the expression of AMPs

Two sequences specific siRNAs (HcToll4-siRNA and HcToll5-siRNA) were respectively injected into mussels to silence the HcToll4 or HcToll5 expression and further reveal the role of HcToll4 and HcToll5 in vivo. HcToll4 or HcToll5 mRNA level was significantly down-regulated at 36 h in the gills of mussels by siRNAs as compared with that in the control groups (Figures 6A,D). After HcToll4 or HcToll5 was knocked down, HcThe (Figures 6B,E), and HcWAP (Figures 6C,F) mRNAs were significantly down-regulated as compared with those without RNAi treatments, suggesting that HcToll4 and HcToll5 might be involved in regulating AMP (HcThe and HcWAP) expression.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of HcToll4 or HcToll5 and detection of HcThe and HcWAP expressions. qRT-PCR analysis of the RNA interference efficiency of HcToll4 (A) or HcToll5 (D) in gills of H. cumingii. The experiments were divided into four groups (normal group, 36 h Vibrio challenge group, Vibrio 36 h plus Toll-scrambled-siRNA group, and Vibrio 36 h plus Toll-siRNA group). Expression of HcThe mRNA in mussels after injection with HcToll4-siRNA (B) or HcToll5-siRNA (E) at 36 h. Expression of HcWAP in mussels after injection with HcToll4-siRNA (C) or HcToll5-siRNA (F) at 36 h. Five mussels were used in each group in this assay. Different asterisks indicate significant differences between groups, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The experiment was repeated three times.

Discussion

As a significant class of proteins involved in the innate immunity of vertebrates, TLRs could provide the first step of defense against pathogens by recognizing PAMPs (Medzhitov, 2001). In invertebrates, Tolls are also involved in innate immunity by binding the ligand of Spätzle (Valanne et al., 2011). Many Toll genes were obtained from a de novo transcriptomic library of H. cumingii. In our previous study, we cloned and characterized five HcToll receptors, including HcToll1, HcToll-I, HcToll2-1, HcToll2-2, and HcToll3 (Ren et al., 2013, 2014; Cao et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). These HcTolls participate in H. cumingii innate immunity. Two other Toll (HcToll4, HcToll5) genes were identified in H. cumingii to study the diversity of Tolls in freshwater mussels. Compared with previously identified Tolls in H. cumingii, HcToll4 and HcToll5 have different domain structures. No LRR_CT domain could be found in HcToll4, whereas HcToll5 has only 1 LRR_CT domain. LRR_CT domain free Toll was rarely reported. In H. cumingii, HcToll3 also has no LRR_CT domain (Zhang et al., 2017). HcToll1 and HcToll2 both have two LRR_CT domains (Ren et al., 2013, 2014). Similar to HcToll3, HcToll4, and HcToll5 both have a LRR_NT domain located behind signal peptide (Zhang et al., 2017). From the phylogenetic tree, HcToll4 and HcToll5 showed closer relationship with HcToll3 than HcToll1, HcToll2s, and HcToll-I. TIR domain is an intracellular signaling domain found in IL-1 receptors, Toll receptors, and MyD88s and mediates the interactions between Tolls/TLRs and signal-transduction components. When activated, TIR domains recruit MyD88 and Toll interacting protein (Mitcham et al., 1996; Kawai and Akira, 2010). Similar to most found invertebrate Tolls, HcToll4, and HcToll5 both have one TIR domain located at the C-terminal of Tolls. In our previous research, we found a Toll with tandem TIR domains in the C-terminal (Ren et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2016). The genome of Pacific oyster contains two distinct loci encoding Tolls with 2 TIR domains; these Tolls were named as twin-TIR Tolls (Gerdol et al., 2017). Multiple Tolls found in H. cumingii suggested that the expansion and diversification of Tolls in H. cumingii genome.

Studying the expression level of functional genes in different tissues is useful to further understand their functions. Both HcToll4 and HcToll5 mRNA transcripts were most abundant in hepatopancreas. The hepatopancreas, which function for the fat body of insects and liver of mammals, are involved in humoral immune responses of invertebrates (Gross et al., 2001). The abundance of HcToll4 and HcToll5 in hepatopancreas may suggest their roles in the innate immune defense of H. cumingii. HcToll2 also showed high expression levels in hepatopancreas (Ren et al., 2014) but no expression in the hemocytes of H. cumingii. By contrast, the Toll genes from C. farreri (CfToll) and C. gigas (CgToll) are mainly expressed in hemocytes (Qiu et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2011).

In molluscas, hepatopancreas and gills are often used as target tissues to investigate the function of immune-related genes. In this study, hepatopancreas and gills were selected as our target tissues to investigate the expression pattern of HcToll4 and HcToll5 in H. cumingii presented with four different kinds of immune challenges. HcToll4 and HcToll5 transcripts showed different expression patterns with different immune challenges. In the gills or hepatopancreas with bacterial challenge, HcToll4 or HcToll5 was upregulated at one or more time points. However, HcToll4 in hepatopancreas was not upregulated at any time point of virus or virus analogs challenge and was down-regulated at 24 h virus or virus analog challenge. CfToll transcript was up-regulated 6 h after LPS challenge (Qiu et al., 2007). CgToll was induced by Vibrio splendidus challenge (Zhang et al., 2011). In hemocytes, C. nobilis CnTLR1 was induced by V. parahaemolyticus, LPS and Poly I:C challenges (Lu et al., 2016).

Vibrio is the most common bacterial pathogen in the mussel farming industry and is also used in immune challenge experiments (Tubiash et al., 1970). Vibrio injection could up-regulate the transcriptions of two AMP genes (HcThe and HcWAP). RNAi of HcToll4 or HcToll5 showed that the expression of HcThe and HcWAP was significantly inhibited. AMPs are one of the most important humoral factors that afford resistance to pathogen infection. Theromacin from H. cumingii possessed anti-bacterial feature, and its gene expression was up-regulated by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Xu et al., 2010). The WAP domain has diverse functions, including proteinase inhibition (Sallenave, 2000) and anti-microbial activity (Wiedow et al., 1998). Crustin is a cationic cysteine-rich AMP that contains a single WAP domain at the carboxyl terminus and acts against microbial pathogens via both anti-bacterial and agglutinative activities (Arockiaraj et al., 2013). Invertebrate WAP proteins are critical in the host immune response against microbial invasion (Li et al., 2013). Therefore, HcToll4 and HcToll5 might have important roles in anti-vibrio immune defense by regulating the expression of AMP genes.

Ethics statement

We declare that appropriate ethical approval and licenses were obtained during our research.

Author contributions

YH and QR: designed the experiments; YH, KH, and QR: carried out the experiments; YH and QR: wrote the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer SA and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Acknowledgments

The current study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31572647), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20171474), Natural Science Fund of Colleges and universities in Jiangsu Province (14KJA240002), and the Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.00133/full#supplementary-material

References

- Akira S., Takeda K., Kaisho T. (2001). Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2, 675–680. 10.1038/90609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armant M. A., Fenton M. J. (2002). Toll-like receptors: a family of pattern-recognition receptors in mammals. Genome Biol. 3:REVIEWS 3011. 10.1186/gb-2002-3-8-reviews3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj J., Gnanam A. J., Muthukrishnan D., Gudimella R., Milton J., Singh A. (2013). Crustin, a WAP domain containing antimicrobial peptide from freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii: immune characterization. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 34, 109–118. 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvin M. P., Anderson K. V. (1996). A conserved signaling pathway: the Drosophila toll-dorsal pathway. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 393–416. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B. A. (2009). TLRs and innate immunity. Blood 113, 1399–1407. 10.1182/blood-2008-07-019307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilak H., Tauszig-Delamasure S., Imler J. L. (2003). Toll and toll-like receptors in Drosophila. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 648–651. 10.1042/bst0310648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie A., O'Neill L. A. (2000). The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: signal generators for pro-inflammatory interleukins and microbial products. J. Leukoc. Biol. 67, 508–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Chen Y., Jin M., Ren Q. (2016). Enhanced antimicrobial peptide-induced activity in the mollusc Toll-2 family through evolution via tandem Toll/interleukin-1 receptor. R. Soc. Open Sci. 15, 3:160123. 10.1098/rsos.160123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carty M., Bowie A. G. (2010). Recent insights into the role of Toll-like receptors in viral infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 161, 397–406. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04196.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdol M., Venier P., Edomi P., Pallavicini A. (2017). Diversity and evolution of TIR-domain-containing proteins in bivalves and Metazoa: new insights from comparative genomics. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 70, 145–164. 10.1016/j.dci.2017.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross P. S., Bartlett T. C., Browdy C. L., Chapman R. W., Warr G. W. (2001). Immune gene discovery by expressed sequence tag analysis of hemocytes and hepatopancreas in the Pacific White Prawn, Litopenaeus vannamei, and the Atlantic White Prawn, L-setiferus. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 25, 565–577. 10.1016/S0145-305X(01)00018-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetru C., Hoffmann J. A. (2009). NF-κB in the immune response of Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1:a000232. 10.1101/cshperspect.a000232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann J. A., Reichhart J. M. (2002). Drosophila innate immunity: an evolutionary perspective. Nat. Immunol. 3, 121–126. 10.1038/ni0202-121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imler J. L., Zheng L. (2004). Biology of toll receptors: lessons from insects and mammals. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75, 18–26. 10.1189/jlb.0403160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T., Akira S. (2010). The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384. 10.1038/ni.1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B., Hoffmann J. (2007). The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 697–743. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Jin X. K., Guo X. N., Yu A. Q., Wu M. H., Tan S. J. (2013). A double WAP domain-containing protein Es-DWD1 from Eriocheir sinensis exhibits antimicrobial and proteinase inhibitory activities, PLoS ONE 8:E73563. 10.1371/journal.pone.0073563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Zheng H., Zhang H., Yang J., Wang Q. (2016). Cloning and differential expression of a novel toll-like receptor gene in noble scallop Chlamys nobilis with different total carotenoid content. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 56, 229–238. 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. (2001). Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1, 135–145. 10.1038/35100529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. (2007). Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature 449, 819–826. 10.1038/nature06246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitcham J. L., Parnet P., Bonnert T. P., Garka K. E., Gerhart M. J., Sims J. E. (1996). T1/ST2 signaling establishes it as a member of an expanding interleukin-1 receptor family. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5777–5783. 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palti Y. (2011). Toll-like receptors in bony fish: from genomics to function. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 35, 1263–1272. 10.1016/j.dci.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L., Song L., Xu W., Ni D., Yu Y. (2007). Molecular cloning and expression of a Toll receptor gene homologue from Zhikong Scallop, Chlamys farreri. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 22, 451–466. 10.1016/j.fsi.2006.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Q., Lan J. F., Zhong X., Song X. J., Ma F., Hui K. M. (2014). A novel Toll like receptor with two TIR domains (HcToll-2) is involved in regulation of antimicrobial peptide gene expression of Hyriopsis cumingii. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 45, 198–208. 10.1016/j.dci.2014.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Q., Zhong X., Yin S. W., Hao F. Y., Hui K. M., Zhang Z. (2013). The first Toll receptor from the triangle-shell pearl mussel Hyriopsis cumingii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 34, 1287–1293. 10.1016/j.fsi.2013.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallenave J. M. (2000). The role of secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor and elafin (elastase-specific inhibitor/skin-derived antileukoprotease) as alarm anti-proteinases in inflammatory lung disease. Respir. Res. 1, 87–92. 10.1186/rr18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake H., Sekiguchi T. (2012). Toll-like receptors of deuterostome invertebrates. Front. Immunol. 3:34. 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toubiana M., Gerdol M., Rosani U., Pallavicini A., Venier P., Roch P. (2013). Toll-like receptors and MyD88 adaptors in Mytilus: complete cds and gene expression levels. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 40, 158–166. 10.1016/j.dci.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubiash H. S., Colwell R. R., Sakazaki R. (1970). Marine vibrios associated with bacillary necrosis, a disease of larval and juvenile bivalve mollusks. J. Bacteriol. 103, 271–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valanne S., Wang J. H., Rämet M. (2011). The Drosophila Toll signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 186, 649–656. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedow O., Harder J., Bartels J., Streit V., Christophers E. (1998). Antileukoprotease in human skin: an antibiotic peptide constitutively produced by keratinocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 248, 904–909. 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Wang G., Yuan H., Chai Y., Xiao Z. (2010). cDNA sequence and expression analysis of an antimicrobial peptide, theromacin, in the triangle-shell pearl mussel Hyriopsis cumingii. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 157, 119–126. 10.1016/j.cbpb.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. W., Huang Y., Man X., Wang Y., Hui K. M., Yin S. W., et al. (2017). HcToll3 was involved in anti-Vibrio defense in freshwater pearl mussel, Hyriopsis cumingii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 63, 189–195. 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. L., Li L., Zhang G. F. (2011). A Crassostrea gigas Toll-like receptor and comparative analysis of TLR pathway in invertebrates. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 30, 653–660. 10.1016/j.fsi.2010.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.