Abstract

Background and aim

Thoracic radiation therapy (XRT) for cancer is associated with the development of significant coronary artery disease that may require coronary artery bypass grafting surgery (CABG). Contemporary acute surgical outcomes and long-term postoperative survival of patients with prior XRT have not been well characterised.

Methods

This was a retrospective, single-centre study of patients with a history of thoracic XRT who required CABG and who were propensity matched against 141 controls who underwent CABG over the same time period. The objectives were to assess early CABG outcomes and long-term survival in patients with prior XRT.

Results

Thirty-eight patients with a history of previous thoracic XRT underwent CABG from 1994 to 2013. The median time from XRT exposure to surgery was 7.9 years (IQR: 2.5–18.4 years). Perioperative adverse events were similar in the XRT group and controls; however, there was a trends lower utilisation of internal mammary artery (IMA) grafts in the XRT group (89%vs98%, P=0.13). After a median postoperative follow-up of 5.4 years (IQR 0.9–9.4 years), no difference in long-term all-cause mortality was observed.

Conclusion

Patients with prior thoracic XRT who undergo CABG have similar long-term all-cause mortality compared with controls. Isolated CABG after thoracic XRT is not associated with higher perioperative complications, but IMA graft use may be limited by prior XRT.

Keywords: coronary artery bypass graft surgery, external beam radiation therapy, radiotherapy, radiation heart disease

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Thoracic radiation is known to accelerate the development of coronary, pericardial and valvular heart disease. Conflicting data have been published on the impact of previous radiation on the outcomes of cardiac surgery, but these data may be confounded by the need for combined coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and valvular surgery and patient comorbidities.

What does this study add?

This was a propensity-matched study of patients undergoing isolated CABG without the confounding impact of combined valve surgery. When compared with controls, patients with previous radiation exposure did not experience an increase in surgical complications and had similar long-term survival. However, there was a non-significant trend towards fewer internal mammary artery (IMA) grafts.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Previous radiation did not increase postoperative complications or long-term mortality in isolated CABG patients, but fewer IMA grafts were used. The survival benefit of CABG is driven by IMA to left anterior descending artery grafts. Preoperative IMA angiography should be performed, and if a suitable IMA is not identified, percutaneous revascularisation should be considered as it has been proven safe and effective in this population. Furthermore, this population is at increased risk for later development of valvular disease, and by avoiding an early sternotomy for coronary revascularisation, the risk of subsequent valve surgeries may be lessened.

Introduction

External beam radiation therapy (XRT) is used for a wide range of malignancies and has substantially improved cancer survival.1 2 As cancer survival has improved, the long-term sequelae related to radiation heart disease are becoming more prevalent. Radiation heart disease is associated with a high incidence of ischaemic heart disease that requires revascularisation.3 4 Coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) improves long-term survival in patients with obstructive left main coronary artery or triple vessel disease.5–8 However, in patients with previous thoracic XRT, cardiac surgery has been associated with increased perioperative complications and higher long-term mortality.9–13 The contemporary performance of isolated CABG in the XRT population has not been adequately assessed, and given recent trial data supporting the role of percutaneous interventions in treating three vessel and left main coronary disease, it is critical to establish the relative risks and benefits of surgical revascularisation in this potentially high-risk population.7 14–16 Therefore, the aim of our study was to determine long-term outcomes following CABG in patients with prior thoracic radiation.

Materials and methods

Study population

This was a single-centre, retrospective study of patients who received thoracic XRT and isolated CABG at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota). The study was conducted without external funding, and all patients provided written consent to participate in this institutional review board-approved study. Radiation patients were cross-referenced with our institution’s Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database from 1994 to 2013 to identify individuals who underwent thoracic XRT prior to CABG. Thirty-eight patients were identified who received XRT treatment for thoracic cancer prior to CABG. Propensity-matched controls were selected from CABG patients treated over the same time period but without previous thoracic XRT exposure. Propensity-score matching was performed on multiple clinical and procedural factors (online supplementary table 1). All patients had a history of cancer and were treated with standard XRT or intensity-modulated radiotherapy (table 1). All CT XRT simulation plans were reviewed by a radiation oncologist, and cardiac involvement in the radiation field was confirmed. Patients treated with palliative intent XRT and those in whom the XRT field did not involve the heart were excluded. Patients undergoing combined CABG and valvular surgery were also excluded to avoid the introduction of significant confounders. Patients treated with combined CABG and pericardiectomy were included as we have not found the addition of pericardiectomy to increase operative risk. Radiation patients more frequently require combined CABG and valve replacement when compared with controls, which would introduce selection bias into the matching process due to greater comorbidity and increased operative morbidity and mortality in those with radiation valve disease.

Table 1.

Location and type of cancer in the study cohorts

| Cancer type | n (%) |

| Breast | |

| Left side | 6 (16) |

| Right side | 7 (18) |

| Bilateral | 0 |

| Unspecified | 7 (18) |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 7 (18) |

| Lung | 6 (16) |

| Oesophageal | 2 (5) |

| Mediastinum | 2 (5) |

| Stomach | 1 (3) |

| >1 type of cancer | 0 |

The primary outcome of this study was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included procedural characteristics such as the number of diseased coronary vessels, number of vessels bypassed, number of internal mammary artery (IMA) grafts used and periprocedural adverse events including death, bleeding, infection, sternal dehiscence, neurological complications, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction (MI), atrial fibrillation, renal failure and length of stay. Surgical outcomes data were collected using our institution’s STS database. Institutional all-cause mortality is updated monthly using hospital registration data. To ensure patients who died at outside institutions are also captured, patients are cross-referenced annually with publicly available national death records using Accurint (LexisNexis, Dayton, Ohio).

Statistical methods

Continuous variables are summarised as mean±SD. Discrete variables are summarised as a frequency and percentage. Tests of difference for continuous variables were performed with a paired t-test for normally distributed data and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normally distributed data. When calculating descriptive statistics, weighting was used to account for the different number of referent subjects matched to each XRT case. A propensity score was created using logistic regression. Optimal variable matching was used with up to four reference subjects matched to each XRT patient.17 Reference subjects were chosen according to age (within 5 years), sex, date of operation (within 2 years) and propensity score (within 1/4 of the SD of the propensity score distribution). Conditional logistic regression was used to test the difference between XRT subjects and their matched controls. Among patients with previous XRT exposure, risk factors for mortality were assessed using univariate Cox proportional hazards to estimate HRs and their associated 95% CIs. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate all-cause mortality. To test differences in survival, Cox proportional hazards models were applied with a frailty term for each set of matched subjects. Follow-up time is measured starting from the date of CABG to date of death or censor. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.3 or higher. All hypotheses tests were two sided with a 0.05 significance level.

Results

A total of 38 patients underwent CABG after thoracic XRT (XRT group: median XRT to CABG interval 7.9 years, IQR: 2.5–18.4 years). We identified 141 matched control subjects with CABG who had not been treated with XRT. Baseline clinical characteristics for the study population are in table 2. XRT-treated patients and matched controls were similar. Controls were more likely to have isolated CABG compared with the study population (99% vs 84%, P=0.002), driven by pericardiectomy in five XRT patients. Of the five XRT patients undergoing pericardiectomy, two were performed for constrictive pericarditis and three were performed prophylactically due to the intraoperative finding of pericardial thickening. One control patient underwent pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis. The number of diseased vessels, prevalence of triple vessel disease and number of bypassed vessels was similar in XRT subjects and matched controls. Despite these similarities, there was a trend towards lower utilisation of IMA grafts in the XRT group (89% vs 98%, P=0.13). The incidence of periprocedural adverse events was similar between XRT group and controls (table 3). Antecedent XRT exposure did not result in higher rates of sternal dehiscence, bleeding, infection or atrial fibrillation.

Table 2.

Baseline clinical characteristics at time of CABG

| Variable, n (%) | XRT group (n=38) |

Control group (n=141) | P value |

| Age, years | 67.9±11.4 | 67.5±11.0 | 0.54 |

| Male gender | 14 (37) | 52 (37) | 1.00 |

| Body mass index (mean±SD) | 28.6±7.0 | 29.7±5.5 | 0.22 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (21) | 39 (28) | 0.41 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 34 (89) | 127 (90) | 0.78 |

| Hypertension | 30 (79) | 121 (86) | 0.25 |

| Congestive heart failure | 5 (13) | 13 (9) | 0.47 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (mean %±SD) | 56.4±11.3 | 54.0±13.7 | 0.31 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 7 (18) | 35 (25) | 0.56 |

| Prior PCI | 9 (24) | 30 (21) | 0.78 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5 (13) | 35 (25) | 0.09 |

| Pre-CABG creatinine (mean±SD, mg/dL) |

1.1±0.3 | 1.1±0.4 | 0.65 |

| Current or former tobacco use | 17 (45) | 76 (54) | 0.33 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 7 (18) | 24 (17) | 0.71 |

| Left main disease | 18 (47) | 62 (44) | 0.78 |

| Aortic cross clamp time (mean±SD) | 48±21 | 49±21 | 0.52 |

| Estimate STS risk (mean %,±SD) | 2.9±3.8 | 2.7±2.2 | 0.99 |

| Angina | 0.99 | ||

| No angina | 11 (29) | 41 (29) | |

| Stable angina | 19 (50) | 71 (50) | |

| Unstable angina/acute coronary syndrome | 8 (21) | 30 (21) | |

| Procedure | 0.002 | ||

| CABG only | 32 (84) | 139 (99) | |

| CABG plus ASD or PFO repair | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| CABG plus pericardiectomy | 5 (13) | 1 (1) | |

| Urgency of CABG | 0.76 | ||

| Elective | 19 (50) | 64 (45) | |

| Urgent | 17 (45) | 74 (53) | |

| Emergent | 2 (5) | 3 (2) |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; XRT, radiation therapy; ASD, atrial septal defect; PFO, patent foramen ovale.

Table 3.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics and outcomes at the time of CABG

| Variable | XRT group (n=38) |

Control group (n=141) | P value |

| Number of diseased vessels (mean±SD) | 3.8±0.5 | 3.7±0.5 | 0.76 |

| Number of vessels bypassed (mean±SD) | 2.9±1.0 | 3.0±0.9 | 0.99 |

| Number of IMA grafts used, n (%) |

34 (89) | 137 (98) | 0.13 |

| Pedicled harvest* | 26 (74) | 100 (78) | 0.74 |

| Length of stay, days, (mean±SD) |

7.3±4.6 | 6.9±3.3 | 0.71 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | |||

| Bleeding | 2 (5) | 5 (3) | 0.59 |

| Infection (any) | 5 (13) | 12 (9) | 0.41 |

| Superficial infection of the venous harvest site | 0 | 3 (2) | |

| Urinary tract infection | 4 (10) | 9 (6) | |

| Bacteraemia | 1 (3) | 0 | |

| Sternal infection | 0 | 0 | |

| Sternal dehiscence | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Neurological complication | 0 | 6 (5) | 0.08 |

| Permanent stroke | 0 | 2 (1) | 0.34 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 0.34 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Atrial fibrillation | 11 (29) | 45 (32) | 0.60 |

| Renal failure | 1 (3) | 2 (1) | 0.90 |

| Inhospital death | 0 | 1 (1) | 0.50 |

*Harvest method was unavailable in three subjects in the XRT group and 12 in the controls.

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; IMA, internal mammary artery; XRT, radiation therapy.

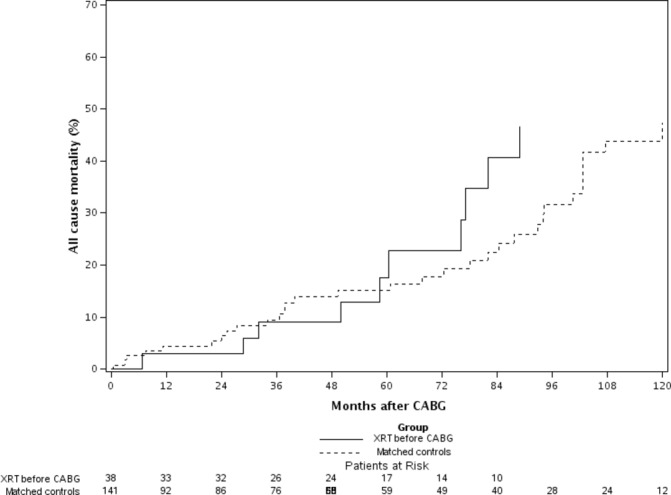

After a median postoperative follow-up of 5.4 years (IQR 0.9–9.4 years), there was no difference in all-cause mortality between the XRT group and controls (figure 1). Eleven deaths occurred in the XRT group, and 32 deaths occurred in the controls.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve. HR: 1.13; 95% CI 0.57 to 2.27; P=0.72. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; IMA, internal mammary artery; XRT, radiation therapy.

Using unadjusted Cox proportional hazards models none of the baseline variables were found to be significantly associated with increased mortality (table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of the effect of previous external beam radiation on mortality in patients treated with CABG

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.86 (0.54 to 1.38) | 0.535 |

| Gender (male) | 0.87 (0.26 to 2.98) | 0.826 |

| BMI (per 5 kg/m2) | 1.03 (0.68 to 1.55) | 0.901 |

| Diabetes | 0.87 (0.20 to 3.82) | 0.859 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 0.48 (0.07 to 3.37) | 0.458 |

| Hypertension | 0.67 (0.18 to 2.49) | 0.555 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.66 (0.45 to 6.12) | 0.449 |

| LVEF (per 10%) | 0.69 (0.43 to 1.11) | 0.123 |

| Prior MI | 0.72 (0.12 to 4.35) | 0.725 |

| Prior PCI | 0.65 (0.11 to 3.90) | 0.637 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.35 (0.22 to 8.16) | 0.743 |

| Pre-CABG creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.23 (0.02 to 2.63) | 0.235 |

| Current/former smoker | 2.32 (0.68 to 7.89) | 0.179 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2.64 (0.67 to 10.4) | 0.165 |

| Left main disease | 2.73 (0.74 to 10.1) | 0.131 |

| STS risk (per 5%) | 1.50 (0.88 to 2.56) | 0.139 |

| Harvest-skeletonised | 0.24 (0.01 to 5.05) | 0.361 |

BMI, body mass index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

We did note a trend towards decreased utilisation of IMA grafts in XRT patients versus controls despite having an equal incidence of triple vessel disease and three vessel bypass. Of the XRT patients who did not receive an IMA (n=4, (11%)), all four had obstructive left main or left anterior descending artery disease that would warrant IMA grafting. In two of these patients, the left IMA was documented in the operative note as being unusable due to luminal fibrosis and occlusion. In the remaining two patients, the operative note does not mention the reason the IMA was not used. In the control population, three (2%) patients did not receive IMAs; reasons included isolated right coronary disease, severe subclavian stenosis and severe osteoporosis with concern for sternal dehiscence. In no control was the IMA itself compromised. In both the study and control population who did not receive IMA grafts, there is no documentation in the operative note as to why a right IMA or radial arterial graft was not used.

Discussion

We observed no difference in all-cause mortality for XRT patients who later received CABG when compared with control subjects. Additionally, thoracic radiation exposure did not increase perioperative adverse events. These findings contrast with those of Wu et al, where increased mortality was observed in radiation patients treated with cardiac surgery.9 Importantly, Wu et al examined a heterogeneous group of patients, only 14% of whom underwent isolated CABG. The remaining patients underwent replacement of ≥1 cardiac valves with or without combined CABG or pericardiectomy. In our population, patients undergoing valve replacement were excluded to facilitate an unbiased match with controls and to better answer the specific question of how XRT impacts surgical revascularisation outcomes. In this population of CABG patients without significant valvular heart disease, procedural outcomes and long-term mortality were similar to controls, suggesting that XRT itself does not increase surgical revascularisation risk.

Multiple studies have documented an adverse effect of XRT on IMA integrity and this likely accounts for the observed difference in IMA utilisation.12 13 18 19 In a 1992 study of 10 patients undergoing CABG after XRT, seven patients received IMA grafts and three patients were revascularised with vein grafts only.18 In two of the three patients with venous only conduits, histological examination of the IMAs was performed and demonstrated fibrosis occluding the arterial lumen, a finding that may have been demonstrated on preoperative angiogram had it been performed. A 1999 series of 47 XRT patients undergoing CABG by Handa et al 13 found in 5 of the 26 patients who received a saphenous vein graft to the left anterior descending artery (LAD), the IMA was unusable due to mediastinal fibrosis. This contrasts with Gansera et al 11 where a similar incidence of histological fibrosis was seen on IMA specimens taken from XRT and control patients. However, it is important to note the low utilisation of IMAs for both the XRT and control groups in the Gansera study, with 16% of patients receiving no IMA grafts. In our study, 11% of XRT patients did not receive an IMA despite having an indication for IMA grafting. In the controls, 2% did not receive an IMA; however, these patients either had no indication for an IMA graft or had a contraindication to using the IMA. The low utilisation of IMA grafts in XRT patients has significant clinical implications as the IMA has been demonstrated to provide the greatest survival benefit to patients undergoing CABG.20–22 In XRT patients without a viable IMA, consideration should be given to alternative arterial conduits such as a free radial artery or right gastroepiploic artery. If a viable arterial conduit is not available, PCI revascularisation should be considered as it is associated with fewer complications and a shorter recovery time. Several trials have supported the safety and efficacy of PCI in treating left main and triple vessel disease.14 15 We have previously reported our institutional experience showing similar rates of acute procedural complications, late stent failure, cardiac mortality and all-cause mortality after PCI in patients with prior XRT compared with control patients without prior XRT.23 24 Furthermore, many radiation patients go on to develop significant valvular disease that may necessitate additional cardiac surgeries at a later date.13 By avoiding an early sternotomy for coronary revascularisation, the risk of subsequent valve surgeries may be lessened. The IMAs are typically not injected during preoperative angiography as they are nearly always patent in the non-XRT population. However, in patients with thoracic XRT exposure, routine preoperative IMA angiography should be considered to assess patency and thereby guide the revascularisation strategy.

An additional concern in XRT patients is the long-term patency of IMA grafts. In a 2008 study of 25 patients with previous chest XRT undergoing postoperative angiography, 32% of IMAs had ≥70% stenosis at 2.2-year follow-up.12 Despite this, late survival was superior in patients with an IMA graft to LAD when compared with patients with venous conduits only. These findings suggest that if the IMA is viable, it should be used for LAD grafting, a finding that has been well demonstrated in the non-XRT population.

Limitations

This research has several important limitations; primary among them is the exclusion of patients who were treated with radiation outside of our institution. We sought to include only patients in whom cardiac involvement within the radiation field could be confirmed, and therefore, patients who received XRT therapy elsewhere were excluded. This resulted in higher quality of data but a smaller sample size. An additional limitation is the heterogeneity in the amount and type of radiation delivered to individual patients. Before the late 1980s, radiation doses of 35–41 Gy were administered to patients with Hodgkin’s disease. Modern regimens now employ 20–30 Gy delivered to smaller volumes.25 Unfortunately, doses of 45–50 Gy are still employed in locally advanced breast cancer, although often through beams passing tangentially through the distal ventricles.26 These differences in XRT exposure by type of cancer and year of treatment may confound our results as the incidence and severity of radiation heart disease is proportionate to dose exposure.10

Additionally, we were unable to differentiate cardiac and non-cardiac mortality. For surgical patients, mortality data are obtained from institutional medical records and using publicly available death certificates that do not record the cause of death. The cause of death was available in the medical record for only a small minority of patients who died at a Mayo Clinic Hospital and therefore was not reported. Clearly, for patients with XRT-associated heart disease, we are most interested in long-term cardiac prognosis. That being said, all-cause mortality is inclusive of cardiac mortality and would be prone to over-represent mortality in the XRT-treated cohort due to the high prevalence of secondary cancers. However, despite this potential confounder, no difference in all-cause mortality was observed.

Conclusions

Our study has demonstrated that in patients with prior thoracic XRT exposure, surgical revascularisation in the contemporary era can be performed with a safety profile similar to control patients. In this cohort, radiation did not increase surgical complications but may limit IMA use. The survival advantage of CABG is driven by IMA to LAD grafts, and therefore, preoperative IMA angiography should be considered. If a viable IMA is not identified, consideration for fully percutaneous revascularisation should be entertained.

openhrt-2017-000766supp001.docx (14.4KB, docx)

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Contributors: All participants made substantive contributions to the research project and writing of this article and are included as authors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Retrospective study. Patients signed institutional consent forms at the time medical care was provided.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available. Requests for data sharing will be reviewed by the institution and granted in accordance with Mayo Clinic’s data sharing policies.

References

- 1. Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. . Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;366:2087–106. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Specht L, Yahalom J, Illidge T, et al. . Modern radiation therapy for hodgkin lymphoma: Field and Dose guidelines From the International lymphoma radiation oncology Group (ILROG). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;89:854–62. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P, et al. . Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:987–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Galper SL, Yu JB, Mauch PM, et al. . Clinically significant cardiac disease in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma treated with mediastinal irradiation. Blood 2011;117:412–8. 10.1182/blood-2010-06-291328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. . 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2011;124:e652–735. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823c074e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Park SJ, Ahn JM, Kim YH, et al. . Trial of everolimus-eluting stents or bypass surgery for coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1204–12. 10.1056/NEJMoa1415447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, et al. . Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2009;360:961–72. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, et al. . Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1607–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa1100356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu W, Masri A, Popovic ZB, et al. . Long-term survival of patients with radiation heart disease undergoing cardiac surgery: a cohort study. Circulation 2013;127:1476–84. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chang AS, Smedira NG, Chang CL, et al. . Cardiac surgery after mediastinal radiation: extent of exposure influences outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:404–13. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gansera B, Schmidtler F, Angelis I, et al. . Quality of internal thoracic artery grafts after mediastinal irradiation. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:1479–84. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown ML, Schaff HV, Sundt TM. Conduit choice for coronary artery bypass grafting after mediastinal radiation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;136:1167–71. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Handa N, McGregor CG, Danielson GK, et al. . Coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with previous mediastinal radiation therapy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;117:1136–43. 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70250-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stone GW, Sabik JF, Serruys PW, et al. . Everolimus-eluting stents or bypass surgery for left main Coronary Artery disease. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2223–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1610227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mäkikallio T, Holm NR, Lindsay M, et al. . Percutaneous coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass grafting in treatment of unprotected left main stenosis (NOBLE): a prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016;388:2743–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32052-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park SJ, Kim YH, Park DW, et al. . Randomized trial of stents versus bypass surgery for left main coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1718–27. 10.1056/NEJMoa1100452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ming K, Rosenbaum PR. Substantial gains in bias reduction from matching with a variable number of controls. Biometrics 2000;56:118–24. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Son JA, Noyez L, van Asten WN. Use of internal mammary artery in myocardial revascularization after mediastinal irradiation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992;104:1539–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hicks GL. Coronary artery operation in radiation-associated atherosclerosis: long-term follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;53:670–4. 10.1016/0003-4975(92)90331-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cameron A, Davis KB, Green GE, et al. . Clinical implications of internal mammary artery bypass grafts: the Coronary Artery Surgery Study experience. Circulation 1988;77:815–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.77.4.815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Loop FD, Lytle BW, Cosgrove DM, et al. . Influence of the internal-mammary-artery graft on 10-year survival and other cardiac events. N Engl J Med 1986;314:1–6. 10.1056/NEJM198601023140101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cameron AA, Green GE, Brogno DA, et al. . Internal thoracic artery grafts: 20-year clinical follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;25:188–92. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00332-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liang JJ, Sio TT, Slusser JP, et al. . Outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention with stents in patients treated with thoracic external beam radiation for cancer. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:1412–20. 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fender EA, Liang JJ, Sio TT, et al. . Percutaneous revascularization in patients treated with thoracic radiation for cancer. Am Heart J 2017;187:98–103. 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eichenauer DA, Engert A, André M, et al. . Hodgkin’s lymphoma: ESMO clinical practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014;25(Suppl 3):iii70–5. 10.1093/annonc/mdu181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Højris I, Overgaard M, Christensen JJ, et al. . Morbidity and mortality of ischaemic heart disease in high-risk breast-cancer patients after adjuvant postmastectomy systemic treatment with or without radiotherapy: analysis of DBCG 82b and 82c randomised trials. Radiotherapy Committee of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. Lancet 1999;354:1425–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02245-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2017-000766supp001.docx (14.4KB, docx)