State of knowledge

Nutrients and immune-inflammatory response in RA

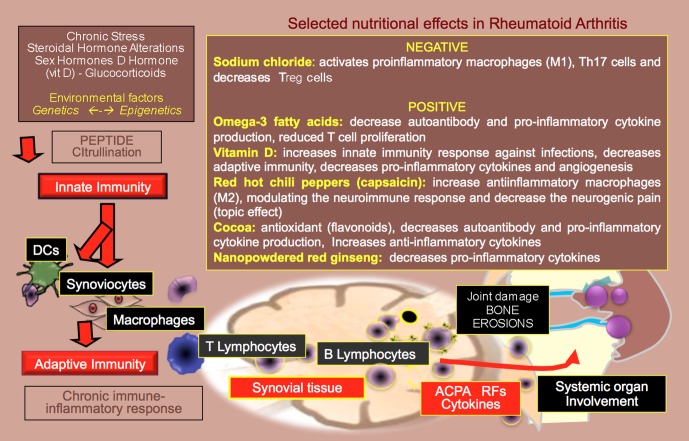

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is characterised by a systemic immune-inflammatory response, in genetically susceptible individuals exposed to environmental and endogenous triggers, including specific nutrients.1 The major pathways in RA are characterised by an intense inflammatory response, involving impaired immunoregulatory processes and the production of different proinflammatory mediators.2 Research on possible risk factors has traditionally focused on triggers setting off disease, such as microbial/viral agents, cigarette smoking and environmental pollution, hormonal imbalance and chronic stress, but with less focus in the past few decades on nutritional factors that can influence disease onset, progression and outcomes, possibly through epigenetic mechanisms.2

More recently, simple and daily dietary factors have been implicated in the development of RA, even directly through triggering inflammatory pathways: for example, the recent evidence that increased sodium chloride salt (figure 1), activates proinflammatory macrophages (M1), Th17 cells and decrease T-regulator cells, all crucial players in RA pathogenesis.3 In addition, sodium excretion was recently found higher in patients with early RA than in matched controls.4

Figure 1.

Cells and mediators of the immune-inflammatory ‘cascade’ leading to overt clinical rheumatoid arthritis are described. Selected nutritional effects on components of the ‘cascade also indicated. ACPA, anticitrullinated peptides autoantibodies; DCs, dendritic cells; RFs, rheumatoid factors.

Other interferences exerted by nutrients like cocoa, ginseng or capsaicin (pepper) on the RA pathways and mediators are reported in figure 1 and discussed in greater detail below.

Despite accumulating evidence over time, the important role that the diet plays on human health in general and more specifically in chronic conditions such as RA, has been subject to much controversy. This has had direct impact on the most important stakeholders, the patients, who are the most frequent active seekers and ‘consumers’ of this crucial information.

Evidence for the possible role of different ‘fatty diets’ in models and patients with RA

An important reason for rheumatologists needing to pay attention to nutrition is in order to help control inflammation by encouraging the use of anti-inflammatory diets and decreasing the use of proinflammatory ones. The notion of ‘inflammatory foods’ is becoming increasingly recognised across chronic diseases such as RA. The ‘modern diet’5 especially practised in Western cultures could be viewed as the greatest enemy of chronic inflammatory conditions like RA, whereby the increased consumption of refined carbohydrates, vegetable oils rich in omega-6 fatty acids and decreased consumption of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids represent ‘the perfect nutritional storm’.6 Supporting these observations, animal data have confirmed that a low ratio of n-6/n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) reduces adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats.7

Since the 1980s and early 1990s where health education initiatives advocated the consumption of antifat diets, in more recent times dietary fats have been increasingly recognised to have a positive impact on health and arthritis.8 Animal studies support that by inducing a collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), in a model of RA in mice consuming high-fat diet (HFD), a risk factor for RA, is related to inflammation but responds minimally to medication. HFD-CIA mice had a high level of α2-glycoprotein 1 (Azgp1), a soluble protein that stimulates lipolysis and fat los that causes increased IL-17; therefore, those mice showed more severe CIA. The same findings are observed in patients with RA.9 Of particular interest, a recent study showed that obese mice fed with HFD had an earlier onset of CIA compared with mice on regular diet, with even a more sustained joint inflammation in obese mice.10 As a matter of fact, despite established RA disease being unaffected by obesity, the early and the resolution phases of RA are impacted by obesity through different mechanisms. For example, conditioned media from RA adipose tissue can transform RA and wild-type naïve myeloid cells into M1 proinflammatory macrophages.10

On the other hand, the benefits of omega-3 fatty acids (figure 1) and of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) (key components of the Mediterranean diet) in controlling disease activity in RA have been published11 and also shown in human clinical trials.12 13 In addition, obesity, a global health problem, represents an important and rising comorbidity even on first presentation of RA14 and appears to be a key determinant of insulin resistance, even more so than circulating proinflammatory cytokines.15

What has been specifically shown for patients with RA and what has not

Further important nutritional aspects have been specifically shown for patients with RA. Taking a focus on the nutritional effects of RA pharmacotherapy, one cannot ignore the established side effects related to the disease-modifying treatments (DMARDs) including the anchor drug in RA, that is methotrexate,16 causing some kind of ‘iatrogenic malnutrition’, whether this is due to nausea, stomatitis, upset stomach, diarrhoea and other.

For some of the DMARDs, the gastrointestinal side effects can be particularly prominent with consequences on nutritional status and thus, indirectly, RA disease outcomes. Furthermore, the widespread and non-optimised use of glucocorticoids (GCs) (high dosages, at the wrong time and of prolonged duration) can be ‘blamed’ at least for the well assessed increased weight gain/body mass index and diabetes. The further interaction between some of these conditions adds to the disease burden in RA and requires specific dietary/pharmacological management.17 Therefore, as rheumatologists we should at the very least encourage reduction or elimination of carbohydrates and high sugar content foods and beverages in our patients with concomitant GC use.

Another important aspect in RA relates to the effects of pregnancy, where there exists strong evidence on the epigenetic/‘therapeutic’ effects of pregnancy states, due to the intense steroid hormonal changes; adherence to the Mediterranean diet during fetal development are key factors in the protection from metabolic syndrome (MS9.18 On the other hand, it is supportable, but not specifically shown, that omega-3 PUFA (n-3 PUFA) supplementation of the maternal diet in pregnancy may provide a non-invasive intervention with significant potential to prevent the development of allergic and possibly other immune-mediated diseases, including RA.19

Furthermore, revolutionary treatments for RA, such as the TNF inhibitors, are becoming standard practice for most of the 21st century and despite their impressive potential to reduce or even halt overexpression of proinflammatory cytokines, they are not effective by themselves, for example, in increasing muscle mass. In fact, they increase fat mass and related metabolic/nutritional consequences.20 21

Microbiome, diet and RA

The emerging role of the gut microbiome in RA must also be considered as evidence supports its impact on nutrition and disease progression.22 The human body contains millions of commensal bacteria (the microbiome), with the bowel being the most prevalent site of colonisation. The process of colonisation begins at birth, and despite interfering factors such as diet and drug use affecting the microbiome composition, by adulthood the gut bacteria are relatively consistent across local populations. Manipulation of the microbiome in inflammatory arthritis, both in animal and human models, offers a potential therapeutic target.22

For example, probiotics have been shown to lower the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 in RA, although how this translates to clinically apparent effects remains unclear, emphasising the need for high-quality trials to investigate these links and prove or disprove the effects on clinically apparent disease.23 Probiotics contain living healthy bacteria such as Bifidobacteria, Bacteroides-Porphyromonas-Prevotella, Bacteroides fragilis and the Eubacterium rectale-Clostridium coccoides species, that are significantly reduced in the gut microbiome of patients with RA. In contrast, bacteria such as Prevotella copri are found in 75% of people with new, untreated RA and are considered a possible risk factor for triggering disease.

A more a healthy diet (fibres) may lead to a more healthy gut microbiota, less active immune system and inflammatory reactions in the gut and finally leading to less inflammation systemically.24–27

As matter of fact, a healthy gut microbiota also releases food metabolites that are anti-inflammatory for the gut immune system and epithelium such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFA). The SCFA are regarded as one of the major microbial metabolites formed by microbial fermentation of dietary fibres, which can improve intestinal mucosal immunity,28

Therefore, recent randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs) seem to provide evidence that specific probiotic supplementation exhibits anti-inflammatory effects, helps to increase daily activities and alleviates symptoms in patients with RA.29

Why rheumatologists should care about diet in RA

Direct and indirect therapeutic effects of specific nutrients in RA

Referring to a recent example of potential therapeutic effects of nutrients in RA, red hot chili peppers (capsaicin) (figure 1) have been suggested to play anti-inflammatory roles by increasing anti-inflammatory macrophages (M2), modulating the neuroimmune response and decreasing neurogenic pain (topic effect).30 Recent research has focused on the evaluation of the efficacy of dietary antioxidants such as the phytomolecules31 and Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), an endogenous antioxidant,32 with positive effects. Cocoa (figure 1) represents another nutrient of increasing interest because of its antioxidant properties, which are mainly attributed to the content of flavonoids such as (-)-epicatechin, catechin and procyanidins.33 In addition, regulatory activity on the secretion of inflammatory mediators from macrophages and other leucocytes in vitro has been proven to be exerted by cocoa.

Interestingly, nanopowdered red ginseng (NRG) (figure 1) used together with methotrexate in arthritic mice significantly reduced cytokines including TNF-a, IL-6 and IL-1b and IgM and IgG1 and suggested the effectiveness of NRG at least in preventing type II collagen-induced RA in mice.34 Such observations about specific nutrients also trigger questions around the value of supplementation in chronic inflammatory diseases such as RA.

Keeping a focus on evidence-based medicine, one important nutritional aspect in chronic immune/inflammatory diseases such as RA is related to the role and level of vitamin D, or better-said, the D hormone, since it is a true steroid hormone synthesised in the skin from 7-dh-cholesterol under the action of the ultraviolet (UV) sun radiations.35 Since only 20% of the daily need of vitamin D can be obtained by the diet (80% from UV), vitamin D supplementation is a more accepted practice with important control (as steroid hormone) of both innate and adaptive immune response, especially with increasing recognition that vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency is a frequent observation in RA (figure 1).36

Patient-reported outcomes in RA appear to be of value in detecting/predicting by clinical symptoms, the effects of the epidemic deficiency of vitamin D/D hormone in Europe and especially during the winter.36 Further adding to the evidence base, data from a recent large study suggest that higher intake of dietary vitamin D as well as omega-3 fatty acids, during the year preceding DMARD initiation may be associated with better treatment results in patients with early RA.37

Rheumatoid cachexia

Another important reason nutrition should not be neglected in RA is in order to prevent and/or treat ‘rheumatoid cachexia’. Evidence suggests that any ongoing, uncontrolled and chronic inflammatory process in RA, involves adverse effects on body composition, including in particular reduced muscle and increased fat mass.37 38 Rheumatoid cachexia refers to these effects, which although rarely apparent, due to the loss of lean body mass being counter-balanced by the maintenance or gain in fat mass,38 is associated with poor prognosis.39

Evidence also suggests that nutrition should be part of routine care in patients with RA with muscle wasting disorders.40 More specifically, up to 75% of patients with RA believe that food and nutrition play an important role in their symptom severity, with 50% of patients with RA reportedly trying some form of dietary manipulation in an attempt to attenuate symptomology.39 40 A previous study investigated the effects of a daily mixture of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate, glutamine and arginine (HMB/GLN/ARG) protein 12-week supplementation in 40 patients with RA with rheumatoid cachexia.41 The results showed that both HMB/GLN/ARG and a control mixture of other non-essential amino acids (alanine, glutamic acid, glycine and serine) were both equally effective in increasing lean mass (~0.4 kg) and improving some measures of physical function and strength.42

In addition, common mental health comorbidities in RA such as depression and anxiety might influence the nutritional status by inducing anorexia-cachexia42 Mental health comorbidities can affect life style and nutritional status43 with detrimental outcomes. In this respect, supplements containing amino acids are believed to be beneficial, since they are converted to neurotransmitters which in turn alleviate depression and other mental health problems.44 These observations further highlight the value of personalising dietary regimes for patients with RA and their respective comorbidities.

Diet and cardiovascular risk in RA

Several clinical, epidemiological and experimental evidence suggest that consumption of the Mediterranean Diet reduces the incidence of pathologies related to the immune system, oxidative stress and chronic inflammation including atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

These reductions can be partially attributed to extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) consumption which has been described as a key bioactive food because of its high nutritional quality and its particular composition of fatty acids, vitamins and polyphenols.45 Indeed, the beneficial effects of EVOO have been linked to its fatty acid composition, which is very rich in MUFA, and has moderate saturated and PUFA.

Several RCTs to assess potential changes in RA inflammation and related cardiovascular (CV) risk after oral intake of ω-3 PUFA have come to light. A meta-analysis evaluating 20 RCTs, involving 717 patients with RA in the intervention group and 535 patients with RA in the control group was recently published. Despite the evidence of overall low quality trials, consumption of ω-3 fatty acids was found to significantly improve eight disease-activity-related markers. Regarding inflammation, only leukotriene B4 was reduced (five trials, P<0.001), whereas a significant amelioration was found for blood triacylglycerol levels (three trials, P=0.012). The beneficial properties of ω-3 PUFA on RA disease activity confirm the results of previous meta-analyses. On the other hand, a large recent study demonstrated that statin therapy is associated with a lower event rate of new-onset acute coronary syndrome in patients with RA, with the beneficial effect being dose-responsive.46

Prevention of metabolic effects of glucocorticoids in RA

Patients who are taking exogenous GCs might also be more susceptible to poor food choices; however, the effect of increased fat consumption in combination with elevated exogenous GCs has only recently been investigated.47 These studies have shown that the metabolic effects initiated through exogenous GC treatment are significantly amplified when combined with a HFD. Animal data confirm that rodents on a HFD and elevated GCs demonstrate more glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinaemia, visceral adiposity and skeletal muscle lipid deposition when compared with rodents subjected to either treatment on its own. Exercise has recently been shown to be a viable therapeutic option for GC-treated, high-fat fed rodents. Clinically, these mechanistic studies again underscore the importance of a low-fat diet and increased physical activity levels when patients, like in the case of patients with RA, are given a course of GC treatment. In fact, even at low doses, prednisolone exerts adverse effects on fat metabolism, which could exacerbate insulin resistance and increase CV risk.48

Conclusion

All these observations lead us to further stress and conclude that nutrition matters and importantly in RA, it plays a role in disease progression and outcomes. Although origins of our understanding of diet and disease stem back to paleontological times,49 the subject seems to be receiving some ‘revival’ in modern times. Despite this, nutrition and the impact on chronic musculoskeletal disease including RA remain a poorly taught subject, both in medical schools and in postgraduate rheumatology training. One would argue that addressing nutrition in our patients is not the ‘job’ of a rheumatologist, but instead of a dietician. Whereas this may be partly true, rheumatologists are the ones who come face to face with patients and their families and access to a dietician may not always be easily and readily available or at all possible. Similarly, working closely in a multidisciplinary team setting with dieticians is certainly optimal, but not always possible. We therefore advocate that at least some basic knowledge on the subject is warranted by rheumatologists in order to appropriately guide on the best ‘recipe’ for their patients with RA.

Acknowledgments

This editorial introduces the recent interest from EULAR to educate rheumatologists and postgraduate to the problem of nutrition in RMD. Supported by the EULAR study group on neuroendocrine immunology of rheumatic diseases (NEIRD).

Footnotes

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: data are elaborated by the authors

References

- 1. Jawaheer D, Seldin MF, Amos CI, et al. . Screening the genome for rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility genes: a replication study and combined analysis of 512 multicase families. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:906–16. 10.1002/art.10989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Edwards CJ, Cooper C. Early environmental factors and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol 2006;143:1–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02940.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van der Meer JW, Netea MG. A salty taste to autoimmunity. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2520–1. 10.1056/NEJMcibr1303292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marouen S, du Cailar G, Audo R, et al. . Sodium excretion is higher in patients with rheumatoid arthritis than in matched controls. PLoS One 2017;12 e0186157 10.1371/journal.pone.0186157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. G S, N R, H M, et al. . Modern Diet and its Impact on Human Health. J Nutr Food Sci 2015;05:1–3. 10.4172/2155-9600.1000430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sears B. Toxic fat : when good fat turns bad: Thomas Nelson, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yu H, Li Y, Ma L, et al. . A low ratio of n-6/n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids suppresses matrix metalloproteinase 13 expression and reduces adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Nutr Res 2015;35:1113–21. 10.1016/j.nutres.2015.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weinberg SL. The diet-heart hypothesis: a critique. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:731–3. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Na HS, Kwon JE, Lee SH, et al. . Th17 and IL-17 Cause Acceleration of Inflammation and Fat Loss by Inducing α2-Glycoprotein 1 (AZGP1) in Rheumatoid Arthritis with High-Fat Diet. Am J Pathol 2017;187:1049–58. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim SJ, Chen Z, Essani AB, et al. . Differential impact of obesity on the pathogenesis of RA or preclinical models is contingent on the disease status. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:731–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gioxari A, Kaliora AC, Marantidou F, et al. . Intake of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition 2018;45:114–24. 10.1016/j.nut.2017.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calder PC. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: from molecules to man. Biochem Soc Trans 2017;45:1105–15. 10.1042/BST20160474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsumoto Y, Sugioka Y, Tada M, et al. . Monounsaturated fatty acids might be key factors in the Mediterranean diet that suppress rheumatoid arthritis disease activity: The TOMORROW study. Clin Nutr 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.02.011 [Epub ahead of print 21 Feb 2017]. 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nikiphorou E, Norton S, Carpenter L, et al. . Secular Changes in Clinical Features at Presentation of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Increase in Comorbidity But Improved Inflammatory States. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:21–7. 10.1002/acr.23014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castillo-Hernandez J, Maldonado-Cervantes MI, Reyes JP, et al. . Obesity is the main determinant of insulin resistance more than the circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines levels in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia 2017;57:320–9. 10.1016/j.rbre.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nikiphorou E, Negoescu A, Fitzpatrick JD, et al. . Indispensable or intolerable? Methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective review of discontinuation rates from a large UK cohort. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:609–14. 10.1007/s10067-014-2546-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strehl C, Bijlsma JW, de Wit M, et al. . Defining conditions where long-term glucocorticoid treatment has an acceptably low level of harm to facilitate implementation of existing recommendations: viewpoints from an EULAR task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:952–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lorite Mingot D, Gesteiro E, Bastida S, et al. . Epigenetic effects of the pregnancy Mediterranean diet adherence on the offspring metabolic syndrome markers. J Physiol Biochem 2017;73:495–510. 10.1007/s13105-017-0592-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dunstan JA, Prescott SL. Does fish oil supplementation in pregnancy reduce the risk of allergic disease in infants? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;5:215–21. 10.1097/01.all.0000168784.74582.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marcora SM, Chester KR, Mittal G, et al. . Randomized phase 2 trial of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for cachexia in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:1463–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Metsios GS, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Douglas KM, et al. . Blockade of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in rheumatoid arthritis: effects on components of rheumatoid cachexia. Rheumatology 2007;46:1824–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jethwa H, Abraham S. The evidence for microbiome manipulation in inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology 2017;56:kew374 10.1093/rheumatology/kew374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mohammed AT, Khattab M, Ahmed AM, et al. . The therapeutic effect of probiotics on rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:2697–707. 10.1007/s10067-017-3814-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Catrina AI, Deane KD, Scher JU. Gene, environment, microbiome and mucosal immune tolerance in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2016;55:391–402. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hotamisligil GS, Erbay E. Nutrient sensing and inflammation in metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:923–34. 10.1038/nri2449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang X, Zhang D, Jia H, et al. . The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment. Nat Med 2015;21:895–905. 10.1038/nm.3914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vaahtovuo J, Munukka E, Korkeamäki M, et al. . Fecal microbiota in early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1500–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Han M, Wang C, Liu P, et al. . Dietary Fiber Gap and Host Gut Microbiota. Protein Pept Lett 2017;24:388–96. 10.2174/0929866524666170220113312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang P, Tao JH, Pan HF. Probiotic bacteria: a viable adjuvant therapy for relieving symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Inflammopharmacology 2016;24:189–96. 10.1007/s10787-016-0277-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deng Y, Huang X, Wu H, et al. . Some like it hot: The emerging role of spicy food (capsaicin) in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2016;15:451–6. 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bala A, Mondal C, Haldar PK, et al. . Oxidative stress in inflammatory cells of patient with rheumatoid arthritis: clinical efficacy of dietary antioxidants. Inflammopharmacology 2017;25:595–607. 10.1007/s10787-017-0397-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abdollahzad H, Aghdashi MA, Asghari Jafarabadi M, et al. . Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Inflammatory Cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) and Oxidative Stress in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Med Res 2015;46:527–33. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramiro-Puig E, Castell M. Cocoa: antioxidant and immunomodulator. Br J Nutr 2009;101:931–40. 10.1017/S0007114508169896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee YK, Choi KH, Kwak HS, et al. . The preventive effects of nanopowdered red ginseng on collagen-induced arthritic mice. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2017;10:1–10. 10.1080/09637486.2017.1358359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cutolo M, Paolino S, Sulli A, et al. . Vitamin D, steroid hormones, and autoimmunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014;1317:39–46. 10.1111/nyas.12432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vojinovic J, Tincani A, Sulli A, et al. . European multicentre pilot survey to assess vitamin D status in rheumatoid arthritis patients and early development of a new Patient Reported Outcome questionnaire (D-PRO). Autoimmun Rev 2017;16:548–54. 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Summers GD, Deighton CM, Rennie MJ, et al. . Rheumatoid cachexia: a clinical perspective. Rheumatology 2008;47:1124–31. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lourdudoss C, Wolk A, Nise L, et al. . Are dietary vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids and folate associated with treatment results in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis? Data from a Swedish population-based prospective study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016154 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Summers GD, Metsios GS, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, et al. . Rheumatoid cachexia and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010;6:445–51. 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stamp LK, James MJ, Cleland LG. Diet and rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2005;35:77–94. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marcora S, Lemmey A, Maddison P. Dietary treatment of rheumatoid cachexia with beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate, glutamine and arginine: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Nutr 2005;24:442–54. 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Norton S, Koduri G, Nikiphorou E, et al. . A study of baseline prevalence and cumulative incidence of comorbidity and extra-articular manifestations in RA and their impact on outcome. Rheumatology 2013;52:99–110. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rao TS, Asha MR, Ramesh BN, et al. . Understanding nutrition, depression and mental illnesses. Indian J Psychiatry 2008;50:77–82. 10.4103/0019-5545.42391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lakhan SE, Vieira KF. Nutritional therapies for mental disorders. Nutr J 2008;7:2 10.1186/1475-2891-7-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Casas R, Estruch R, Sacanella E. The Protective Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil on Immune-mediated Inflammatory Responses. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2018;18:23–35. 10.2174/1871530317666171114115632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huang CY, Lin TT, Yang YH, et al. . Effect of statin therapy on the prevention of new-onset acute coronary syndrome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Cardiol 2018;253:1–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dunford E, Riddell M. The Metabolic Implications of Glucocorticoids in a High-Fat Diet Setting and the Counter-Effects of Exercise. Metabolites 2016;6:44 10.3390/metabo6040044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Radhakutty A, Mangelsdorf BL, Drake SM, et al. . Effects of prednisolone on energy and fat metabolism in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: tissue-specific insulin resistance with commonly used prednisolone doses. Clin Endocrinol 2016;85:741–7. 10.1111/cen.13138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. David AR, Kershaw A, Heagerty A. Atherosclerosis and diet in ancient Egypt. Lancet 2010;375:718–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60294-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]