Abstract

Introduction

Implementation fidelity is a challenge for the adoption of evidence-based home visiting programs within social service broadly and child welfare specifically. However, implementation fidelity is critical for maintaining the integrity of clinical trials and for ensuring successful delivery of services in public health settings.

Methods

Promoting First Relationships® (PFR), a 10-week home visiting parenting intervention, was evaluated in two randomized clinical trials with populations of families in child welfare. Seven providers from community agencies participated in the trials and administered PFR. Fidelity data collected included observational measures of provider behavior, provider records, and input from clients to assess training uptake, adherence to content, quality of delivery, program dosage, and participant satisfaction.

Results

In mock cases to assess training uptake, providers demonstrated an increase in PFR verbalization strategies and a decrease in non-PFR verbalizations from pre-to post PFR training, and overall this was maintained a year later (Mann-Whitney U’s = 0, p’s < .01). Adherence to content in actual cases was high, with M = 97% of the program elements completed. Quality of delivery varied across providers, indicated by PFR consultation strategies (Wilks’ Lambda F = 18.24, df = 15, p < .001) and global ratings (F = 13.35, df= 5, p < .001). Program dosage was high in both trials (71% and 86% receiving 10 sessions), and participant satisfaction was high (M = 3.9, SD = 0.2; 4 = “highly satisfied”).

Discussion

This system of training and monitoring provides an example of procedures that can be used effectively to achieve implementation fidelity with evidence-based programs in social service practice.

Keywords: home visiting, child welfare home visiting program, Promoting First Relationships, service fidelity, home visiting implementation, program quality, participant satisfaction

Introduction

The increase in evidence-based programs makes it possible for child welfare services (CWS) to select programs suited to their population and regional needs, with the caveat that many evidence-based programs have not been tested with CWS families (Lee, Aos, & Miller, 2008). After identification and selection of a program with evidence of effectiveness, an additional challenge is ensuring implementation fidelity. The purpose of this paper is to describe a manualized home-visiting program, Promoting First Relationships® (PFR: Kelly, Sandoval, Zuckerman, & Buehlman, 2008), that was evaluated in two randomized clinical trials with populations of CWS families. We describe tools and methods to increase implementation fidelity, including provider training and use of data to monitor adherence, quality, dosage, and participant satisfaction.

Promoting First Relationships®

PFR was first disseminated in the late 1990s to provide a relationship-based approach to home visiting services that is informed by infant mental health principles. The aim of PFR is to equip service providers with tools, skills, and knowledge necessary to help parents become more emotionally available to their children and increase their understanding of their children’s social and emotional needs. The training and 10-week program intervention have been disseminated to service providers including home visitors, counselors, early intervention providers, child care consultants, and primary care physicians. After this broad dissemination, PFR was evaluated through two randomized clinical trials. To maximize external validity, both trials were conducted in real-world contexts with families in the child welfare system.

The first clinical trial of PFR, which began in 2005, was designed as a community-based effectiveness trial for use with CWS infants and toddlers who had recently experienced a separation from their primary caregiver (Spieker et al. 2012). Known as the Fostering Families Project (FFP), this study was originally designed to test PFR’s effectiveness with foster parents. After input from community members and the local state child welfare agency, the research program was redesigned to include birth parents and kin providers. Thus, all children in the study had experienced a change in primary caregiver through a move to or away from a birth, foster, or kin home. The trial’s results indicated that PFR increased caregiver sensitivity and knowledge of child development (Spieker et al. 2012) and improved permanency for those children who received the program while with a foster or kin caregiver (Spieker et al. 2014). Evidence of some additional positive intervention effects were found among the subsample of reunified birth parents (Oxford et al. 2013, 2016a). In a small pilot study within FFP, children in the PFR condition showed an improvement in cortisol response relative to the control group (Nelson and Spieker 2013).

The second clinical trial, the Supporting Parents Program (SPP), began in 2010. The aim of SPP was to study the impact of PFR on families with parents under investigation by Child Protective Services (CPS) for a report of maltreatment with their infants or toddlers. Results of SPP indicated an improvement in parental sensitivity, an increase in parent knowledge of child development, and 2.5 times fewer subsequent foster care placements in the group receiving PFR (Oxford et al. 2016b). In a small pilot study within SPP, children in the PFR condition also showed improved emotional regulation relative to the control group, as measured by respiratory sinus arrhythmia (Hastings et al. 2017).

Implementation Fidelity

Implementation fidelity is related to outcomes for evidence-based programs (Durlak & DuPre, 2008), but fidelity often falls short in clinical trials that take place in real-world settings (Breitenstein et al., 2010). This may occur because: providers are not well nor uniformly trained; not all intervention components are covered in training, or are covered in an incomplete manner; providers deviate from the program’s protocols and key elements; the full dosage of the program is not delivered; the quality of program delivery lags; or participant responsiveness is low. These factors can combine and interact, reducing the impact of the intervention (Berkel, Mauricio, Schoenfelder, & Sandler, 2011). Thus, a system for ensuring implementation fidelity is crucial.

Fidelity has been defined as multidimensional (e.g., see Berkel et al., 2011). We follow Dane and Schneider’s (1998) identification of key components of implementation and focus on (1) adherence to the content of the program, (2) quality of delivery, (3) program dosage, and (4) participant satisfaction. We describe the system we developed for training program providers, a procedure used to measure training uptake in the SPP trial, and measures for monitoring implementation fidelity of PFR in both trials. We report data that were gathered as part of this system and describe how data were used to achieve implementation fidelity.

Methods

PFR Description

Promoting First Relationships® (PFR) is a program for caregivers with children under age three. It relies heavily on strengths-based video feedback. The standard version of PFR used in research studies consists of 10 weekly one-hour home visits conducted by service providers following a manualized curriculum and using specific consultation strategies. Each week has a unique theme. Each session includes: rapport building, specific PFR consultation strategies, video reflective feedback, parent-child activities, informational handouts, and “Thoughts for the Week” for the caregiver to consider between visits. The provider is trained in the PFR consultation strategies (positive feedback, positive and instructive feedback, and reflective questions and comments) to engage with the parent around the social and emotional needs of the child. During alternating weeks, the provider videotapes the caregiver and child playing. The caregiver and provider reflect on that unedited videotape in the following week’s session. This activity is hypothesized to increase parental confidence, competence and capacity to reflect on the child’s social and emotional needs. To support the providers as they implement the program, weekly reflective practice meetings occur with a PFR consultant.

Study 1: Fostering Families Project (FFP)

FFP recruited 210 toddlers (age 10–24 months) and caregiver dyads. Toddlers in the study had experienced a recent court-ordered placement that resulted in a change in primary caregiver. Caregivers needed to be conversant in English, have stable enough housing to do home visits, and live within a single CWS region in Western Washington. Caregiver-toddler dyads were randomly assigned to PFR or the control condition. Five providers delivering PFR were employees at four different community mental health agencies that volunteered to be a part of the project. Each provider devoted .25 FTE to the study. Four providers were trained at the beginning of the study and an additional provider was hired one year into the study to replace a provider who left. All providers were female, Caucasian, and had Master’s degrees in social work or counseling. The study was approved by the Washington State Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Study 2: Supporting Parents Program (SPP)

SPP enrolled 247 biological parents with children between the ages of 10–24 months who had active CPS cases for an investigation of maltreatment. Participants needed to be conversant in English, have stable housing, and live in the study’s selected ZIP code areas in Western Washington at time of enrollment. Caregiver-child dyads were randomly assigned to PFR or the control condition. SPP trained two community-based PFR providers who worked at a single agency. Both providers applied for the early childhood specialist – mental health therapist position at the agency, each stayed with the study throughout its entirety and devoted .5 FTE. Both were female, Caucasian, and had Master’s degrees in social work or counseling. The study was approved by the Washington State Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Training FFP and SPP Providers

Providers in both studies completed PFR training over the course of 5–6 months. Training involved approximately 77 hours, consisting of a three-day introductory workshop followed by conducting the 10 PFR home visits with three families while being mentored by a master trainer. In these mentored cases, the trainee progressively assumed more leadership in providing the intervention. After each session, trainee and master trainer would debrief, review the client’s videotape, reflect on the needs of the dyad, and plan the next session. To complete the training, trainees were required to demonstrate mastery of the PFR consultation strategies and core content in two video-recorded fidelity sessions.

Measures of Training Uptake and Implementation Fidelity

Training uptake

In the SPP study, we used a procedure to assess changes in how providers worked with families prior to and after training in PFR. We wanted to capture the change in verbal behavior over time, as we anticipated that providers would become more skilled in the use of PFR consultation strategies and relationship-focused practice. Prior to receiving PRF training, each provider trainee was videotaped conducting intervention sessions with actors playing the part of parents. Five of these “mock” sessions were conducted pre-PFR training, five immediately after PFR training, and a final five one-year post-training. Providers were given a videotape of an actual parent-child interaction, similar to one they would record during a PFR session, and a description of the parent and child including concerns about the dyad. A single PFR master trainer coded all of the mock sessions.

Adherence to content

In both FFP and SPP, providers completed a checklist that consisted of 54 PFR elements, separated into weekly segments with approximately five PFR elements (activities) each week. For example, each week began with a check-in, followed by videotaping or video viewing, discussing handout(s), and presenting a “Thoughts for the Week” worksheet to encourage the caregiver to reflect on the topic over the next week – each of these activities is a PFR element. The provider updated this checklist after each visit, documenting the providers’ adherence to delivering the PFR curriculum as intended. The checklist provided a fidelity check on the content of the delivery. For each provider, the indicator was the number of activities completed divided by the total number of activities in the protocol, based only on the PFR weekly sessions completed. Although this was a self-report measure and could be subject to bias, the providers knew that this was only used as a tool to document the intervention for research, did not affect their fidelity ratings, and was not shared with their employers.

Quality of delivery

In both the FFP and SPP studies, PFR providers videotaped themselves during the video feedback that occurred during session #8 with each dyad from their caseloads. The tapes averaged 20 minutes in length. The PFR master trainer reviewed these videotapes and coded them for quality of delivery in both studies. All provider utterances during these sessions were coded to create counts of each PFR consultation strategy: positive feedback, positive and instructive feedback, and reflective questions and comments. In addition, “other” talk was counted. “Other” talk included giving advice or talking about events that were not contained in the video. One measure of quality of delivery was based on the ratio of PFR verbalization strategies to “other” talk.

Another measure of quality was a global rating of the entire videotaped segment. The rating ranged from 1 = “no PFR strategies being used, provider not relationship-focused” to 5 = “provider using all PFR strategies, is solidly focused on the dyadic relationship, makes the reflective dialogue rich and meaningful for the caregiver”. The global rating reflected the judgment of the PFR master trainer. If a provider’s global rating fell below 4 for any single videotape, she was not assigned any new cases. The provider continued to serve the families on her caseload, and received additional one-on-one mentoring, including reviewing her videotapes with the master trainer. Areas of weakness were addressed explicitly in order to increase the provider’s fidelity to the program. She was assigned new cases again when a session received a global rating of 4 or greater.

Program dosage

In both FFP and SPP, dosage was captured by the number of sessions completed with caregivers. Program completion was 10 sessions.

Participant satisfaction

In SPP, parents were given a 10-item questionnaire during their last session and provided with an addressed, stamped envelope so that they could complete and return the questionnaire to the research office. Parents were informed that their feedback would be confidential and not shared in an identified manner with the providers. The items, rated on a 4-point scale (1= “NO!” to 4= “YES!”), measured aspects of satisfaction with and perceived usefulness of the program, as well as negative experiences (reversed coded). There was also an open-ended question for additional comments. The overall satisfaction score was the mean of the 10 items. The measure had adequate reliability (Chronbach’s α=.77). Participant satisfaction was not collected in FFP.

Results

Training uptake

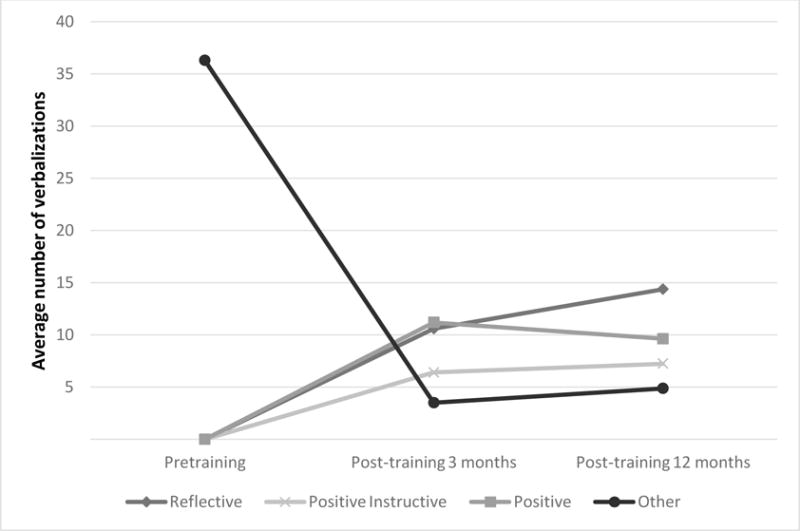

The results from the mock sessions conducted with SPP providers, which measured the uptake of training procedures, are shown in Figure 1. Verbalizations across all “mock” sessions were counted and averaged. The providers were not using any positive feedback, positive and instructive feedback, or reflective questions and comments prior to PFR training. Their talking consisted of “other” comments that were not relationship-focused PFR consultation strategies. After PFR training, providers used all three PFR verbal consultation strategies and greatly reduced their use of “other” comments. This general pattern was maintained over time. For both providers, differences between pre-training totals and both post-training and 12-month totals for each of the four consultation types were statistically significant at p=.008, based on the two-tailed exact p-values for a Mann-Whitney U test (U = 0).

Figure 1.

Quality of delivery: Mean count of PFR and “other” verbalizations in mock sessions, pre- and post-training

Adherence to content

In both FFP and SPP, results from the adherence checklists showed that almost all of the 5–6 weekly elements of the intervention were covered in each completed session (e.g., joining, videotaping, reflecting on the videotape, discussing handouts, viewing a PFR video, doing specified activities). The percent of elements completed was calculated for each case. In both studies, an average of 97% of the elements were completed by the seven providers (ranging from 78% to 100%).

Quality of delivery

Table 1 shows the average count of each PFR consultation strategy by provider in both studies based on the fidelity videos. Provider 5 had lower fidelity scores than the other six providers, consistently not reaching fidelity. While Provider 5 made frequent use of positive feedback and reflective questions, use of positive and instructive feedback was low and the provider engaged in more “other” talk. The average global rating of this provider was also below the expectations for the program. After a year of mentoring and close monitoring of her work with seven families, she was still unable to consistently reach fidelity. Based on mutual agreement, Provider 5 left the study.

Table 1.

The Average Count of the Number of PFR Verbal Consultation Strategies, “Other” Verbalizations, and Global Quality Ratings by Provider Based on Coding of Fidelity Tapes with SPP and FFP Participants

| Average Number of Verbalizations Representing PFR Strategies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive feedback | Positive + instructive feedback | Reflective questions | Non-PFR “other” comments | Ratio of PFR verbal strategies to “other” comments | Global rating | ||

| Provider | # of tapes | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| 1 | 42 | 7.3 (2.4) | 4.7 (2.3) | 8.6 (3.9) | 2.5 (1.3) | 13.4 (9.1) | 4.4 (0.7) |

| 2 | 49 | 7.0 (2.8) | 6.4 (2.7) | 6.0 (2.6) | 2.6 (1.4) | 11.5 (6.9) | 4.7 (0.5) |

| 3 | 21 | 12.1 (4.1) | 13.1 (5.1) | 12.6 (4.2) | 1.6 (1.2) | 29.7 (13.5) | 5.0 (0.0) |

| 4 | 20 | 14.6 (5.8) | 6.6 (2.9) | 9.2 (7.0) | 2.8 (2.9) | 16.8 (9.8) | 4.5 (0.5) |

| 5 | 6 | 10.0 (3.5) | 3.3 (3.3) | 12 (5.2) | 10.8 (4.4) | 2.6 (1.7) | 3.0 (0.6) |

| 6 | 21 | 9.6 (4.5) | 6.5 (4.1) | 7.4 (5.3) | 4.1 (3.8) | 9.1 (6.1) | 3.9 (0.9) |

| 7 | 43 | 4.3 (1.7) | 5.5 (2.3) | 4.8 (2.5) | .84 (.75) | 13.8 (4.4) | 4.1 (0.6) |

We ran a one-way MANOVA model to assess differences among PFR consultation totals (positive, positive and instructive, and reflective) on all providers except Provider 5, as that provider was an outlier. MANOVA results indicated that providers significantly varied in their use of the strategies (Wilks’ Lambda F = 18.24, df =15, p < .001). Post-hoc tests indicate that Provider 3 differed significantly from all other providers due to her high use of all PFR verbalization strategies, which is reflected in her very high ratio of PFR strategies to “other” talk.

The PFR global score is a more subjective rating than the count of verbalizations reported above. The global score captures the coder’s overall assessment of quality of service delivery. Scale points are anchored by descriptive statements. Based on analyses that excluded Provider 5, there was significant variation among providers in global scores (F = 13.35 df= 5, p <.001), with Provider 3 receiving a global quality score of 5 on all of her videotaped sessions.

Program dosage

In FFP, 71% of the 105 caregivers in the PFR condition received all ten sessions. This rate was higher in SPP with 86% receiving all ten sessions. Within each study, the individual providers did not deliver significantly different dosages. Attendance was lower in the FFP project because more families dropped out due to child placement changes. Most families enrolled in the studies had at least one PFR session and only 6% of FFP families and 7% of SPP families never began the intervention.

Participant satisfaction

Participant satisfaction was only measured in SPP. Eighty-four participants (78.5% of the families that completed the intervention) returned the evaluation forms and the ratings were very high (M=3.9, SD=0.2). Families reported positive feelings about the home visits, noted that the program was useful, and reported positive experiences with the providers. Table 2 presents some of the comments mentioned by parents in SPP.

Table 2.

Comments from PFR Participant Satisfaction Forms

| General Program Comments |

| “This program is/was great. I’d do it again. It helped immensely and I truly feel my provider listened and helped with understanding the communication between me and [my child].” |

| “I thought at first this program was going to be blah but [provider] made it very interesting and made me realize how much I enjoy my baby (kids). Thanks again!” |

| “I like how this program is set up to teach good parenting skills. Thank you. I learned a lot.” |

| Videotaping |

| “I love the fact that I get to see/watch videos of ‘bonding’ time w/my children and see who/how I interact w/them.” |

| “It’s more hands on it’s better being observed while interacting with your child then just some class where you talk” |

| “I think this program is wonderful and very import for children and parents. It’s really fun to watch the videos. I hope other families benefit as much as my family did. Thank you!” |

| “I think back to sitting on the floor with my [child] playing/and remembering the look on his face as if he was proud/happy that I was there taking the time to actually get down on the floor and play with him.” |

| “The videos help me step ‘outside’ the moment & gives me a chance to see room for improvement.” |

| Increased Confidence |

| “It helps me a lot to have someone else outside of my home to talk to and have someone who can relate to me. My children and I adore those quality times together and it makes me realize most things that I don’t see myself doing on a daily basis…” |

| “It made me feel better as a parent to understand and to help them.” |

| “Very useful program in helping a new mom to be sure on right path with communication with my little one. Along with many helpful ideas. Loved the support!” |

| Increased Awareness of Child’s Feelings and Needs |

| “I think this program help me to understand my child more, and I love my provider. She listens to me, and always seems interested in me & my kids. Thank for this program.” |

| “I think this program help build my relationship with my child for the better. It has help me understand him more as a child. I am glad I did this program.” |

| “I learned a lot about how I interact with my child. [Provider] was very helpful, a great listener, and extremely helpful. Would definitely recommend to other parents.” |

| “This program helped me realize how close my daughter is towards me. And my provider was a great listener and gave good advice.” |

| “This program has opened my ‘inner child’ and helped me remember what it was like to be young. I now have a better understanding of how to listen to my child and address his needs concretely.” |

| Use of PFR Principals with Other Relationships |

| “I love the way the program works. It has helped me also with my marriage & my older children. Thank you!!” |

| “We are going to miss [provider], she was wonderful! I love the positive changes in my family’s relationships since we started this program. Looking forward to where we will go from here.” |

| “Our family learned a lot on how to cope with the kids’ emotions. It’s amazing how this program can have one on one interaction with the families and hope that more families will be able to receive this opportunity that we got.” |

Discussion

Implementing a relationship-based intervention program for young children and their caregivers within CWS is challenging. Infancy and toddlerhood is a time of rapid development and families are attempting to balance competing priorities. Issues of intervention standardization and implementation are inherently complex, particularly so when families are facing stressful life circumstances. A degree of flexibility and accommodation is necessary to engage and retain stressed families throughout the course of an intervention. In turn, both instrumental and emotional supports are needed for providers doing the frontline work. In this report, we focused on issues of training and implementation. We described efforts to ensure high implementation fidelity, including the use of data to monitor adherence, quality, dosage, and participant satisfaction, as well as measuring training uptake.

When the focus is on supporting infant mental health in the context of a home-visiting program, clinicians need knowledge, skills, and tools to enhance a caregiver’s capacity to understand a child’s social and emotional needs. The PFR pre- and post-mock visit assessments show that training shifted the content of providers’ verbalizations to caregivers. This pre-post training shift demonstrated that providers gained skill in using PFR strategies to support caregivers’ strengths (through positive and positive-instructive feedback) and enhance capacities to reflect on the underlying feelings and needs of their children, while also considering caregivers’ own feelings and needs as parents (through reflective questions and comments). Providers were also able to use more of the challenging PFR verbalization strategies (reflective questions and instructive feedback) relative to the easier strategy, positive feedback.

One of the more intriguing findings is that the seven providers in the two studies varied considerably in their use of the PFR strategies, reflecting their unique styles. For example, Table 1 shows that Provider 1 used, on average, 4.7 positive instructive verbalizations while Provider 3 used more than twice that number; in both cases the providers maintained fidelity. The number and type of PFR strategies per visit is not predetermined; however, providers do need a global rating of 4 out of 5 to achieve fidelity. One provider consistently reached high fidelity while another did not due to her extensive use of “other” talk. A proscribed approach to service was not a good fit for her. This mismatch may be true of many providers, and is an area for future research. We expect variation in service delivery due to both the providers’ unique styles and the diverse needs of the families they serve. Understanding provider fit and developing self-assessment prior to training in a particular intervention strategy would improve our ability to select appropriate candidates.

PFR is designed to be used flexibly to meet the constantly shifting needs of families. Adherence to the intervention was conceptualized realistically and somewhat fluidly for the community-based implementation with families involved in CWS. Elements of PFR program delivery were tracked with the checklist. However, the sequence of delivery sometimes had to be adjusted to meet the needs of stressed families in crisis. To keep a family engaged, a provider needed to not only be attuned to covering the PFR elements but also responsive and sensitive to each family on her caseload. The quotes and survey data from participants indicated high levels of satisfaction with the program. Caregivers felt supported, listened to, and “seen” by providers, and they felt validated as important in their relationship with their child. Specific elements of the program, e.g., video feedback, resonated with parents as well, bolstering their feelings of confidence and competence.

Consistent across both studies was the importance of reflective practice to maintain fidelity and retain providers. At weekly group reflective practice with a non-supervisory consultant, providers checked in, got support, and reflected on the families in their caseloads. This provided space and time to be more purposeful with families and improve the quality of their work. Additional one-on-one mentoring was important when providers struggled with maintaining fidelity.

Both FFP and SPP trials were conducted in real-world settings where PFR was delivered by community-based providers to CWS-involved families–as it would be in practice as PFR becomes more widely disseminated. For both studies, providers came from agencies partnering with CWS and were newly trained in PFR for the trials. However, our description of implementation fidelity is based on only seven providers in two trials and measures of training uptake and participant satisfaction were only available in one of the trials. Ongoing monitoring of PFR implementation in different settings with larger numbers of providers is needed. In order to maintain fidelity, procedures must be put in place to ensure adequate training, adherence to the intervention, high quality of service delivery, and regular reflective consultation. The procedures used for our research can be applied in real world service settings to improve effectiveness and achieve desired outcomes.

Many factors cannot be controlled when training providers, implementing an intervention with at-risk populations, and evaluating outcomes. However, implementation fidelity and, ultimately, program effectiveness can be improved by training and supporting providers, measuring participant satisfaction, and collecting data to monitor the intervention.

Significance.

What is already known on this subject?

Implementation fidelity is essential to evaluate program effectiveness. Home visiting programs to support the parent-child relationship are growing in use but little is known about how these programs are implemented, and few have been successfully implemented in child welfare.

What does this study add?

This study demonstrates how a home visiting model was implemented in child welfare, how providers were trained, and how fidelity to the model was measured and maintained using data from two randomized clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of a brief 10-week home visiting program.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01HD061362 and U54HD083091, and from the National Institute of Mental Health under Award Number R01MH077329. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, Sandler IN. Putting the pieces together: An integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science. 2011;12(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Garvey CA, Hill C, Fogg L, Resnick B. Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Research in Nursing & Health. 2010;33(2):164–173. doi: 10.1002/nur.20373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dane AV, Schneider BH. Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18(1):23–45. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings P, Kahle S, Fleming C, Lohr M, Katz L, Oxford M. An intervention that increases parental sensitivity in families referred to Child Protective Services also changes toddlers’ parasympathetic regulation. 2017. (Submitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Sandoval D, Zuckerman TG, Buehlman K. Promoting First Relationships: A program for service providers to help parents and other caregivers nurture young children’s social and emotional development. 2nd. Seattle, WA: NCAST Programs; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Aos S, Miller M. Evidence-based programs to prevent children from entering and remaining in the child welfare system: Benefits and costs for Washington. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; 2008. (Document No. 08-07-3901) [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EM, Spieker SJ. Intervention effects on morning and stimulated cortisol responses among toddlers in foster care. Infant mental health journal. 2013;34(3):211–221. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford ML, Fleming CB, Nelson EM, Kelly JF, Spieker SJ. Randomized trial of Promoting First Relationships: Effects on maltreated toddlers’ separation distress and sleep regulation after reunification. Children and youth services review. 2013;35(12):1988–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford ML, Marcenko M, Fleming CB, Lohr MJ, Spieker SJ. Promoting birth parents’ relationships with their toddlers upon reunification: Results from Promoting First Relationships® home visiting program. Children and youth services review. 2016a;61:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford ML, Spieker SJ, Lohr MJ, Fleming CB. Promoting First Relationships®: Randomized trial of a 10-week home visiting program with families referred to child protective services. Child maltreatment. 2016b;21(4):267–277. doi: 10.1177/1077559516668274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieker SJ, Oxford ML, Kelly JF, Nelson EM, Fleming CB. Promoting first relationships: Randomized trial of a relationship-based intervention for toddlers in child welfare. Child maltreatment. 2012;17(4):271–286. doi: 10.1177/1077559512458176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieker SJ, Oxford ML, Fleming CB. Permanency outcomes for toddlers in child welfare two years after a randomized trial of a parenting intervention. Children and youth services review. 2014;44:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]