Abstract

NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenases (FDH, EC 1.2.1.2), providing energy to the cell in methylotrophic microorganisms, are stress proteins in higher plants and the level of FDH expression increases under several abiotic and biotic stress conditions. They are biotechnologically important enzymes in NAD(P)H regeneration as well as CO2 reduction. Here, the truncated form of the Gossypium hirsutum fdh1 cDNA was cloned into pQE-2 vector, and overexpressed in Escherichia coli DH5α-T1 cells. Recombinant GhFDH1 was purified 26.3-fold with a yield of 87.3%. Optimum activity was observed at pH 7.0, when substrate is formate. Kinetic analyses suggest that GhFDH1 has considerably high affinity to formate (0.76 ± 0.07 mM) and NAD+ (0.06 ± 0.01 mM). At the same time, the affinity (1.98 ± 0.4 mM) and catalytic efficiency (0.0041) values of the enzyme for NADP+ show that GhFDH1 is a valuable enzyme for protein engineering studies that is trying to change the coenzyme preference from NAD to NADP which has a much higher cost than that of NAD. Improving the NADP specificity is important for NADPH regeneration which is an important coenzyme used in many biotechnological production processes. The Tm value of GhFDH1 is 53.3 °C and the highest enzyme activity is measured at 30 °C with a half-life of 61 h. Whilst further improvements are still required, the obtained results show that GhFDH1 is a promising enzyme for NAD(P)H regeneration for its prominent thermostability and NADP+ specificity.

Keywords: Coenzyme regeneration, Gossypium hirsutum, Formate dehydrogenase, NADP+ specificity, Thermostability

Introduction

The formate dehydrogenases catalyze the oxidation of formic acid to carbon dioxide by generating two protons and two electrons and they are found in archaea, aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, yeasts, fungi and plants. There are several types of formate dehydrogenases, which differ in their subunit composition and they can be classified as NAD(P)-dependent/metal-independent, NAD(P)-dependent/metal-containing and NAD(P)-independent/metal-containing formate dehydrogenases (Yu et al. 2017; Shabalin et al. 2010). NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenases (FDH, EC 1.2.1.2) are widely found enzymes in methylotrophic microorganisms and higher plants. NAD+-dependent FDHs catalyze the oxidation of formate into CO2 concomitant with the reduction of NAD(P)+ to NAD(P)H, while it also catalyzes the reduction of CO2 into formate under appropriate conditions. Through this reversible reaction system, FDHs are industrially important enzymes in the regeneration of the NAD(P)H coenzyme and the reduction of CO2 to formate, which is a stabilized form of hydrogen fuel. Studies about the biotechnological usage of FDHs have been focusing on the methylotrophic yeasts (Abdellaoui et al. 2017; Junxian et al. 2017; Sungrye et al. 2014; Ordu et al. 2013) and extremophilic microorganisms (Fogal et al. 2015; Davies et al. 2016; Niks et al. 2016; Alissandratos et al. 2013). Now, however, due to developing next-generation sequencing technologies the number of plants which have complete genome sequence information is continuously increasing. Searching databases such as NCBI, EMBL and KEGG shows us that FDHs isolated from plants are only a small part of FDH gene records and the majority of them are hypothetical genes resulting in genomic studies.

While NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenase is involved in providing energy to the cell in the methylotrophic microorganisms, it is a stress protein in plants. The level of FDH expression increases during several environmental stress conditions such as drought, heavy metal, thermal discontinuity, hard ultraviolet, hypoxia and pathogen infection (Lou et al. 2016; David et al. 2010; Igamberdiev et al. 1999). Synthesis against such diverse stress factors suggests that FDH is a universal enzyme and it has a key role in the stress metabolism of higher plants. While there is a wealth of data for the effects of recombinant plant FDHs on plant growth under biotic and abiotic stress conditions, our understanding of kinetic and stability of plant-derived recombinant FDHs is less comprehensive (Lou et al. 2016; David et al. 2010; Alekseeva et al. 2011; Shiraishi et al. 2000). Only a few genes, isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana (Sadykhov et al. 2006), Glycine max (Alekseeva et al. 2012; Kargov et al. 2015) and Lotus japonicus (Andreadeli et al. 2009), give us limited information about the kinetic and stability properties of plant-derived recombinant FDHs. It is obvious that this is an important shortcoming and the biotechnological potential of plant-sourced FDHs need to be evaluated.

In the databases, there are two hypothetical FDH gene records from Gossypium hirsutum. In order to fill the gap between impractical sequence information of hypothetical genes and functional characterization of proteins and, consequently, to determine the utility of Gossypium hirsutum formate dehydrogenase (GhFDH1) in NAD(P)H regeneration and CO2 reduction systems, heterologous expression and characterization of the FDH enzyme from the cotton plant were performed for the first time in the present study.

Materials and methods

Growth conditions of Gossypium hirsutum

Gossypium hirsutum L. seeds were kindly provided from Guven Borzan, Agricultural Engineer, MSc. from East Mediterranean Transitional Zone Agricultural Research Institute, Kahramanmaras, Turkey. Surface sterilization of the seeds was performed with H2SO4, ethanol and sodium hypochlorite treatment based on the protocol of Bıçakçı and Memon (2005). Surface sterilized and uncoated seeds were transferred into magenta vessels containing Murashige and Skoog medium (1/2MS). Seeds were grown in a growth chamber under 16 h a day/8 h photoperiod with 96 µmolm−2s −1 irradiation, air humidity 60–70%, and day/night temperature of 25/23 °C for 21 days.

Bacterial strain and plasmid

Chemically competent Escherichia coli DH5α cells ([F2f80lacZDM15 D(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk 2, mk þ) phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 tonA]) (Invitrogen) were used in this study. Heterologous expression was performed with His-tagged pQE-2 expression vector (Qiagen TAGZyme vector).

Cloning and heterologous expression of formate dehydrogenase cDNA

Root tissues were harvested on the 21st day of growth and ground in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA isolation was performed with the protocol using CTAB, phenol/chloroform and ammonium acetate (Zhao et al. 2012). Purity and concentration of the isolated RNA were determined by micro-volume spectrophotometer (PCRmax Lambda). 1 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed with anchored-oligo (dT)18 primer using Transcriptor High Fidelity cDNA synthesis kit (Roche). Truncated GhFDH1 cDNA, lacking the mitochondrial signal peptide sequence at the N-terminus was amplified by PCR, as described by Andreadeli et al. (2009). Gh-Fwd (5′-CGTCATATGCAAATGATTGTTGGGGTGTTTTAC-3′) and Gh-Rev (ACCGAAGCTTACATCAAGTTCAAAGCACAAT) oligonucleotides, including NdeI and HindIII -sites, were designed. Total volume of 20 µl PCR was set up with 1× Phusion GC buffer, 0.2 mM of dNTP mix, 3% DMSO, 0.5 µM of each primers, 200 ng of first strand cDNA and 0.5 unit of Phusion High Fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB). Thermal conditions of the reaction were as follows: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s, 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 57 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 30 s and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min.

PCR amplicon and expression vector, pQE-2, were digested with 20 units of HindIII and 20 units of NdeI, sequentially. Following gel extraction of the fragments, ligation reaction was set up with T4 DNA ligase (Roche). Chemically competent E. coli cells were then transformed with ligation product and transformants were selected on Luria–Bertani agar containing 100 µg ml−1 ampicillin. Colony PCR was carried out with Taq PCR master mix kit (Qiagen) to select the recombinant pQE-2 harboring clones. Selected clone were grown in terrific broth (with 100 µg ml−1 ampicillin) at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm overnight. 50 ml of overnight culture was inoculated into 1 L of ampicillin containing terrific broth and grown at 37 °C until OD600 reached 0.6. Recombinant GhFDH expression was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG to the growth medium and cells were grown at 24 °C for 16 h, then collected by centrifugation at 4000×g for 20 min and stored at − 80 °C.

Protein purification

GhFDH1 protein from E. coli overexpressing clones was purified as described previously (Ordu et al. 2013). SDS-PAGE was performed with TGX Stain-Free™FastCast™ Acrylamide Kit, 12% (Bio-Rad) on a 1.0 mm thick gel using Mini-PROTEAN® Tetra Vertical Electrophoresis System. Protein bands were visualized with Vilber Lourmat ECX-F20.C transilluminator following 1 min activation under UV light. SDS-PAGE and UV light visualization showed the proteins to be > 95% pure after purification. Protein concentration was determined using the procedure of Quick Start™ Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) and expressed in terms of the monomeric protein concentration using monomer mass of 38650 Da.

Steady-state kinetics

The steady-state kinetic experiments were carried out by using Shimadzu 1800 double beam (10 mm path length) UV–VIS spectrophotometer at 25 °C. To determine the optimum pH of the formate oxidation and CO2 reduction, initial rates of each formate (0–50 mM sodium formate) and hydrogen carbonate (0–50 mM sodium hydrogen carbonate) consumption were determined at 340 nm by measuring the NADH production or depletion in the reactions containing 20 mM buffer, 1 mM NAD+, 0.4 μM enzyme (0.5 mM NADH and 4 μM enzyme for CO2 reduction). 20 mM of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6 and pH 7) and 20 mM of Tris buffer (pH 8 and pH 9) were used as reaction buffers.

Following determination of the optimum pH, kinetic parameters were measured for NAD+ and NADP+. Reactions were set up by adding 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7, 10 mM sodium formate, 0-2.5 mM NAD+ or 0-50 mM NADP+ and 0.4 μM enzyme. Specific activity of the recombinant enzyme was also determined using a reaction solution containing 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7, 10 mM sodium formate, 1 mM NAD+ and 0.4 μM enzyme. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 µmol of NADH per minute under standard conditions (Choe et al. 2014). All experiments were performed in duplicate and each measurement was repeated three times. Data were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation using Grafit 5.

Thermal denaturation

The enzymes were incubated at different temperatures between 30 and 70 by 5 °C intervals for 20 min in triplicate. Remaining activity measurements were performed at 25 °C in a reaction mixture containing 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7, 1 mM NAD+, 10 mM formate and 0.4 μM enzyme. The Tm value referring to the temperature required to reduce the initial activity by 50%, was determined from the plot of residual activity versus temperature using Grafit 5.

The stability of the enzyme against time was studied at the temperatures at which the enzyme gives the highest activity and at the midpoint of thermal inactivation. The aliquots of the purified enzyme in 20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7, were incubated at 30 and 53 °C. Experiments were duplicated and the remaining activity was measured at specific time intervals in triplicates.

Bioinformatic analysis and homology modeling

The constraint-based multiple alignment tool (COBALT) of NCBI was used for the multiple protein sequence alignment (Papadopoulos et al. 2007). Formate dehydrogenases from Candida boidinii (CbFDH, pdb code: 5DN9_A), Pseudomonas sp. 101 (PsFDH, pdb code:2NAD_A), Arabidopsis thaliana (AtFDH, pdb code: 3NAQ_A), and Glycine max (GmFDH, NCBI accession number, NP_001241141.1) were used for alignment. Alignment file and constructed model were uploaded into ESPript 3.0 and both the sequence similarities and secondary structure information were determined from the aligned sequences (Robert and Gouet 2014).

The structure of recombinant GhFDH1 was modeled with SWISS-MODEL homology modeling tool using the apo-form of NAD-dependent FDH from higher-plant Arabidopsis thaliana (AtFDH, pdb code: 3NAQ_A, resolution 1.70 Å) and ligand binds AtFDH (pdb code: 3N7U, resolution 2.0 Å), as template (Arnold et al. 2006).

Results and discussion

Cloning, expression, and purification of GhFDH1

In silico homology searches for plant formate dehydrogenase show that two predicted mitochondrial FDH genes of Gossypium hirsutum are localized on the chromosome 9 (XM_016891386.1) and chromosome 10 (XM_016894382.1) (Li et al. 2015). The FDH gene length on chromosome 10 is 3108 bp and the mRNA sequence is 1639 bp, whereas the FDH gene length on chromosome 9 is 2824 bp and the mRNA sequence is 1535 bp. Six exons and five introns are identified, with introns occurring at the same positions for both predicted FDHs. The only difference is the size of the 5th intron: 487 and 307 bp for chromosome 10 and chromosome 9, respectively. These two FDH proteins have 99% homology and are different only for two amino acids except for the signal peptide sequence. Pro65 and Glu357 residues on chromosome 10 are substituted with glutamine and aspartate amino acids on chromosome 9. In the case of Glu357Asp substitution, no functional difference is expected as negatively charged Glu and Asp amino acids are very similar in terms of structure and electrostatic charge. Although Pro residue has a nonpolar side chain changed with Gln with polar side chain at the position 65, this position is not related to anywhere on the catalytic, NAD+ binding or ligand binding sites or dimerization interface. The N-terminal peptide sequence of FDH on chromosome 10 has MAM motif at position 1–3, similar to a number of plant FDHs such as GmFDH and LjFDH (Alekseeva 2011), while the FDH on chromosome 9 has MQQ motif at the same position (uniprot/A0A1U8PF82 and A0A1U8P6Y5). The mitochondrial signal sequence-truncated and heterologously expressed FDH has 100% identity with the FDH on chromosome 10 and it was designated as GhFDH1 in the present study. Like all plant FDHs, GhFDH1 has a signal peptide sequence at the N-terminus directing it to mitochondria. Since there is no mitochondria in E. coli, we cleaved the sequence, encoding the signal peptide from the cDNA as described in Andreadeli et al. (2009), to be able to express recombinant GhFDH1.

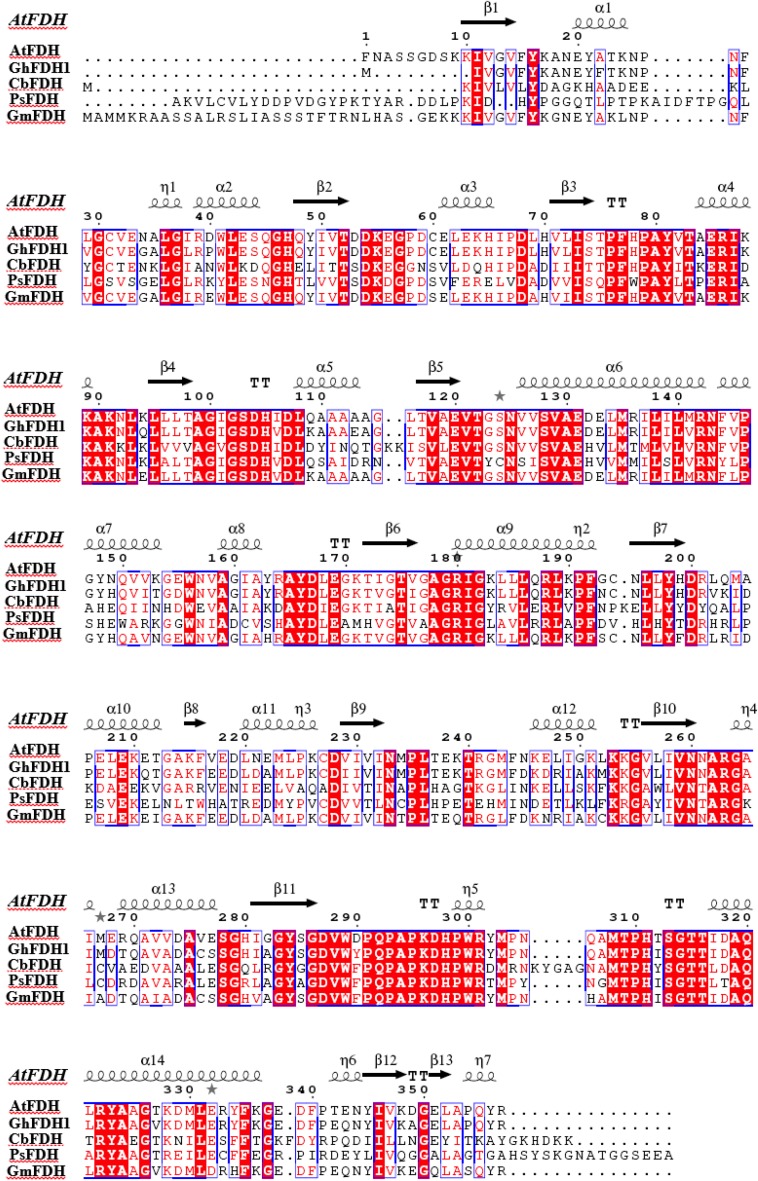

Truncated GhFDH1 gene, without His-tag, contains an open reading frame of 1044 bp, coding for a polypeptide of 348 amino acid residues with a theoretical molecular mass of 38.65 kDa and isoelectric point (pI) of 6.08. Figure 1 shows the amino acid sequence alignments of GhFDH1 resulting from Blast with FDHs from methylotrophic yeast Candida boidinii (CbFDH), prokaryote Pseudomonas sp. 101 (PsFDH) and plants Arabidopsis thaliana (AtFDH) and Glycine max (GmFDH). In addition to the sequence alignment in Fig. 1, GhFDH1 reveals sequence identities of 90%, with predicted mitochondrial FDHs from Herrania umbratica and Theobroma cacao.

Fig. 1.

Amino acid Blast analysis of GhFDH1: sequence alignments of GhFDH1 with other FDHs which have knowledge of crystallographical structure (Arabidopsis thaliana FDH (AtFDH), Pseudomonas 101 sp. FDH (PsFDH), Candida biodinii FDH (CbFDH), and Glycine max FDH (GmFDH) were determined). Conserved residues are highlighted in red and blue frames and indicate that more than 70% of the residues are similar according to physico-chemical properties

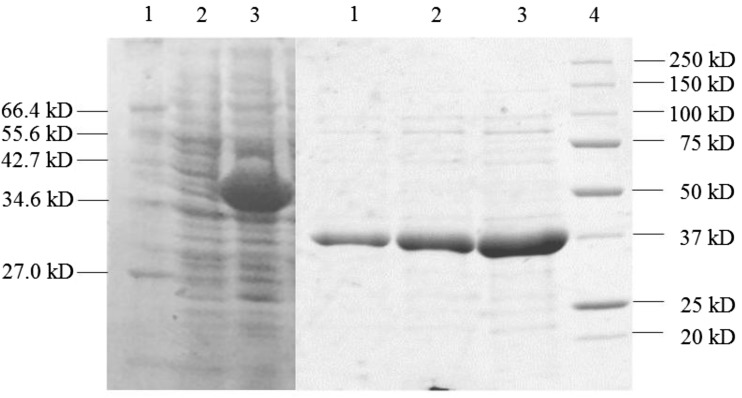

Because the mitochondrial FDHs constitute a small part of all soluble proteins in the cell, direct isolation of the active FDH enzymes from plant tissue cannot be performed in sufficient quantity. Hence, heterologous expression of plant-sourced FDHs is a prerequisite to characterize the function of these enzymes. To determine whether the predicted G. hirsutum protein was a functional FDH, the truncated form of the cDNA lacking the N-terminal signal peptide was amplified by PCR and about 1100-bp length amplicon was obtained. Reaction product was cloned into the pQE-2 expression vector, based on the T5 promoter transcription–translation system for high level expression of the N-terminal 6× His-tagged proteins. Then, E. coli DH5α cells were transformed with pQE-2 expression vector containing His-tagged GhFDH1 cDNA and the enzyme was overexpressed after confirmation of the fdh gene sequence. The soluble GhFDH1 expression in E. coli has been proved, since the crude extract of the E. coli transformants showed a specific activity of 0.046 U/mg protein, as observed in the signal peptide-truncated Lotus japonicus FDH (0.05 U/mg) (Andreadeli et al. 2009) (Fig. 2). The level of expression was raised by incubation at a lower temperature, 24 °C. His-tagged GhFDH1 enzyme was efficiently purified by using nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni–NTA) metal-affinity chromatography. GhFDH1 was purified 26.3-fold and 87.3% of all soluble proteins in the cell was obtained as active formate dehydrogenase (Fig. 2, Table 1). The percentage of purified protein showed that the expression of plant FDH from G. hirsutum in E. coli DH5α cells was successfully performed and its yield was higher than that of FDHs from G. max and A. thaliana (40%) reported in the literature before (Alekseeva 2011).

Fig. 2.

Overexpression and His-tag purification of GhFDH1: expression of GhFDH1 in E. coli DH5αT1. 1. unstained protein marker, broad range (2-212 kDa; NEB); 2. crude extract from uninduced cells; 3. crude extract from induced cells (a). Purified protein with Ni–NTA resin, 1. Elute #3, 2. Elute #2, 3. Elute #1; 4. precision plus unstained protein standards (10-250 kDa; Bio-Rad)

Table 1.

Purification table of GhFDH1 from crude extract

| Purification step | Volume (ml) | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (Units) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Purification (fold) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 7.00 | 121.10 | 5.54 | 0.046 | 1.00 | 100.00 |

| Ni–NTA resin | 2.25 | 4.02 | 4.83 | 1.20 | 26.15 | 87.28 |

Following purification, recombinant protein was characterized for its ability to catalyze formate oxidation, CO2 reduction and thermostability.

Kinetic analysis and the pH effect on the GhFDH1 activity

To determine the pH at which the GhFDH1 enzyme shows optimum activity, the kinetic properties of the recombinant enzyme were investigated over the pH range, 6–9. Results showed that GhFDH1 has optimum activity at pH 7 when the substrate is formate. Catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) at pH 7 is 1.2-, 3.2- and 1.6-fold higher than at pH 6, pH 8 and pH 9, respectively (Table 2). Therefore, steady-state kinetic analyses were performed at pH 7 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Kinetic properties of the recombinant GhFDH1 over pH 6–9, when the substrate is formate

| PH 6 | PH 7 | PH 8 | PH 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (mM) | 1.048 ± 0.10 | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 2.25 ± 0.60 | 1.1 ± 0.60 |

| kcat (s−1) | 0.314 ± 0.00 | 0.295 ± 0.00 | 0.281 ± 0.00 | 0.273 ± 0.00 |

| kcat/Km | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters of GhFDH1 for different substrates at pH 7

| Formate | NAD | NADP | Hydrogen carbonate | NADH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (mM) | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 1.98 ± 0.40 | n.o. | n.o. |

| kcat (s−1) | 0.295 ± 0.00 | 0.759 ± 0.00 | 0.0083 ± 0.00 | n.o. | n.o. |

| kcat/Km | 0.39 | 12.65 | 0.0042 | n.o. | n.o. |

n.o. not observed

The pH of the medium affects the catalytic activity of the enzyme due to the altered ionization of the charged groups in the protein globule. Even a single group’s ionization can cause conformational changes in the protein (Tishkov et al. 2010). Here, the Km of GhFDH1 at pH 9 is lower than the Km at pH 8, whereas kcat did not change at different pHs (pH 6–9); it is thought that the substrate binding affinity changed according to the medium pH and pKa values of the ionizable groups of amino acids. The CO2 reduction activity of the recombinant GhFDH1 enzyme was also tested and any measurable activity was not recorded at all pHs (under the conditions defined in the ‘Materials and methods’ part), when the substrate and coenzyme were sodium hydrogen carbonate and NADH.

The Km values for formate, NAD+ and NADP+ were determined as 0.76 ± 0.07, 0.06 ± 0.01 and 1.98 ± 0.4 mM, respectively. The GhFDH1 has the highest affinity for formate (0.76 mM) more than other recombinant plant FDHs (Table 4), providing an important characteristic for industrial applications. Although FDHs exhibit absolute specificity towards the NAD+ coenzyme generally, GhFDH1 also exhibits activity towards NADP+ similar to plant and some bacterial FDHs (Table 4) such as AtFDH, GmFDH, Burkholderia stabilis FDH (BstFDH) and Granulicella mallensis FDH (GraFDH) (Fogal et al. 2015). However, the catalytic efficiency of GhFDH1 is about 3000 times higher for NAD+ than for NADP+, proving that GhFDH1 is highly specific for NAD+ compared to NADP+ (Table 3). It is known that NAD+ specificity is caused by Asp residue, which is located at the conserved fingerprint sequence GXGXXGX17–18D (Andreadeli et al. 2009). In the GhFDH1 protein, this conserved Asp residue (Asp191) is located at the 18 residue downstream from the Gly residue at the end of the GXGXXGX motif located between the 168th and 173th residues. It is thought that NAD+ specificity is due to interaction between the side chain of this Asp191 and the 2′- and 3′-OH groups of adenosine ribose (Andreadeli et al.2009). Until now, only NAD+-dependent type FDHs (EC 1.2.1.2) have been reported in plants and Asp191 residue is highly conserved in these NAD+ specific FDHs. Differently, in BstFDH (K+mNADP 0.16 mM) and GraFDH (K+mNADP 0.85 mM), which have a high affinity for NADP+, Asp residue at the homologous position of 191, is substituted with glutamine and alanine, respectively (Fig. 1). However, it is thought that the presence of Arg residue in the next position with respect to the conserved Asp191 of GhFDH1 may confer slightly NADP+-dependent activity beside NAD+ specificity, because of Arg residue at this position of BstFDH and GraFDH which have high affinity for NADP+(Fogal et al. 2015). As a result, wild-type recombinant GhFDH1 having the 1.98 mM Кm value for NADP+ is a promising candidate to change the specificity towards NADP+ via coenzyme engineering studies. Changing the coenzyme specificity of oxidoreductases is an important research area. Because changing the coenzyme preference from NAD+ ($ 140 per g) to NADP+ ($ 1000 per g) has a much higher price than that of NAD, it is important to develop systems for NADPH regeneration, which is an important coenzyme used in many biotechnological production processes (Adreadeli et al. 2008; You et al. 2017).

Table 4.

Comparison of kinetics and thermostability parameters of the most reported recombinant FDHs from isolated plants and microorganisms

| FDH source | Km formate (mM) | Km NAD (mM) | Km NADP (mM) | Km hydrogen carbonate (mM) | Km NADH(mM) | Kcat (s−1) | PH | Tm (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gossypium hirsutum FDH | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 1.98 ± 0.40 | n.d. | n.d. | [a] 0.295 ± 0.00 [b]0.759 ± 0.01 [c] 0.008 ± 0.00 |

7.0 | 53 (R.A.) | This study |

| Lotus japonicus FDH1 | 6.1 ± 1.10 | 0.026 ± 0.00 | 29.5 ± 3.20 | n.d. | n.d. | [a] 1.3 ± 0.1 [b] 1.2 ± 0.1 [c]0.01 ± 0.00 |

7.5 | ND | (Andreadeli et al. 2009) |

| Glycine max FDH | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 13.3 ± 0.80 | 1 | n.d. | n.d. | [a] 2.9 ± 0.1 [b] 2.92 [c] n.d. |

7.0 | 57.1 (DSC) | (Alekseeva 2011; Kargov et al.2015) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana FDH | 2.8 | 0.02 | 10 | n.d. | n.d. | [a] 3,8 [b] n.d [c] n.d |

7.0 | 64.9 (DSC) | (Alekseeva 2011) |

| Granulicella mallensis FDH | 80 | 6.5 | 0.85 | n.d. | n.d. | [a] n.d. [b] 5.77 [c] 3.96 |

7.0 | 53 (DSC) | (Fogal et al. 2015) |

| Burkholderia stabilis FDH | 55.50 | 1.43 | 0.16 | n.d. | n.d. | [a] 1.7 ± 0.10 [b] 1.66 [c] 4.75 |

7.0 | ND | (Fogal et al. 2015) |

| Pseudomonas sp. 101 FDH | 6.5 ± 0.20 | 0.065 ± 0.00 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | [a] 7.3 ± 0.20 [b] 7.15 [c] 1.3 ± 0.10 |

7.0 | 67.6 (DSC) | (Alekseeva et al. 2015; Tishkov et al. 2015) |

| Candida boidinii FDH | 5.9 | 0.045 | >38 | 31.30 ± 8.10 | 0.50 ± 0.20 | [a] 3.7 [b] 3.6 [c] n.d. |

7.0 | 64.5 (DSC) | (Sadykhov et al. 2006) (Choe et al. 2014) |

|

Candida

methylica FDH |

4.75 ± 0.30 | 0.62 ± 0.30 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | [a] 1.13 ± 0.10 [b] 0.2 ± 0.10 [c] n.o. |

8.0 | 58 ± 0.81 (R.A.) | (Ordu et al. 2013) Özgün et al. 2015) |

| Thiobacillus sp. FDH | 16.24 ± 5.39 | 0.28 ± 0.08 | n.d. | 9.23 ± 3.98 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | [a] 1.77 [b] 1.77 [c] n.d. |

6.5 | 52.5 | (Choe et al. 2014) (Nanba et al. 2003) |

| Myceliophthora thermophila FDH | 7.20 ± 1.50 | 1.20 ± 0.20 | n.d. | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.003 ± 0.00 | [a] 0.3 ± 0.02 [b] 0.76 ± 0.05 [c] n.d |

10.5 | 48 (R.A.) | (Altaş et al. 2017) |

n.d. not determined, R.A. residual activity, DSC differential scanning calorimetry

[a]: kcat value for formate, [b]: kcat value for NAD, [c]: kcat value for NADP

Thermal stability analysis of GhFDH

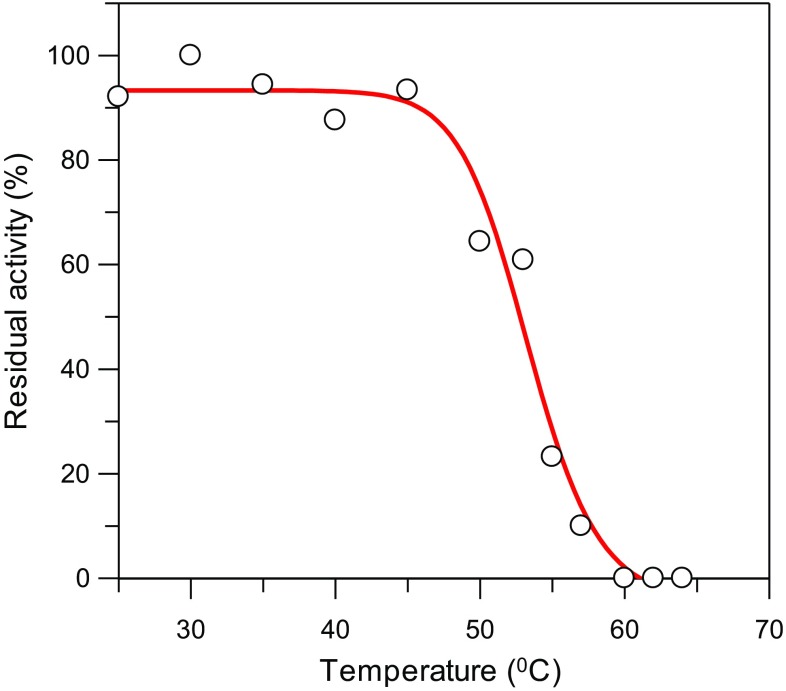

The thermal stability of GhFDH1 was assessed by measuring the midpoint of thermal inactivation (Tm). The enzyme was incubated at a series of temperatures for a period of 20 min, followed by measurements of the residual activity at 25 °C. The activity of the GhFDH1 enzyme reached the highest level at 30 °C (1.06 ± 0.015 U/mg). At temperatures ranging from 25 to 50 °C, GhFDH1 showed the over 60% of the maximum activity. The activity decreased sharply after 55 °C and was lost above 60 °C. The Tm value for GhFDH1 was calculated as 53.3 °C using Grafit 5 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Heat inactivation of GhFDH1: the midpoint of thermal inactivation (Tm) value was determined from the plot of residual activity versus temperature and determined as 53.3 °C. 100% residual activity value is 1.06 ± 0.015 U mg−1

While it is known that the thermal stability of bacterial and yeast enzymes is higher than that of plant FDHs (Sadykhov et al. 2006), the thermostability of GhFDH1 is higher than the FDHs isolated from some extremophilic microorganisms (Choe et al. 2014; Altaş et al. 2017; Ding et al. 2011) (Table 4). When compared with previously reported plant FDHs, and taking into consideration the Tm values obtained from the residual activity and DSC measurements, it is considered that GhFDH1 isolated from cotton, which is a hot climate plant, has a higher thermostability (53.3 °C) among plant FDHs.

Thermal inactivation studies against time were performed by applying the temperature at which the enzyme gives the highest activity (30 °C) and at the midpoint of the thermal inactivation (53 °C). During the incubation at 30 °C, GhFDH1 enzyme activity increased by 12 and 22% at the end of the first and second hour, respectively. The highest activity was measured at the end of the second hour. Thermal inactivation was almost negligible over 24 h at 30 °C. Enzyme activity was over 60% of the maximum activity until the 48th hour and the half-life of the enzyme was 61 h at 30 °C. At the midpoint of thermal inactivation, the enzyme was inactivated in 100 min and showed a half-life of 38 min.

Molecular modeling

ESPript 3.0 was used to determine the secondary structure and to align the sequence of recombinant GhFDH1 with the sequences of some formate dehydrogenases from plants, fungi and bacteria, whose structures were identified by crystallographic techniques (Fig. 1). Soybean FDH (GmFDH) was also included in the alignment, since the SmartBLAST service of NCBI found that GmFDH was among the closest relatives to GhFDH1 (data not shown). Secondary structure elements were depicted based on the structure of AtFDH. Conserved residues are highlighted in red and blue frames and indicate that more than 70% of the residues are similar according to physico-chemical properties. BLASTP 2.6.1 search against the PDB protein database showed that GhFDH1 has 88% sequence identity with AtFDH, 52% identity with CbFDH and 51% sequence identity with FDH from Pseudomonas sp. 101. Furthermore, SmartBLAST analysis of the query showed that GhFDH1 shared 88% identity with GmFDH. Consistent with other plant FDHs, the similarity between the GhFDH1 enzyme and bacterial FDHs was approximately 50%, whereas the homology level between the plant enzymes was above 80% (Aleekseva et al. 2011). Residues located in the substrate and NAD+ binding sites, Ile92, Asn116, Asp191, and Asp278, and also two important residues for catalytic activity, Arg254 and His302 are conserved in the aligned sequences of the enzymes. These amino acids are also conserved among different plant FDHs from Lotus japonicus, Solanum tuberosum and Hordeum vulgare (Andreadeli et al. 2009).

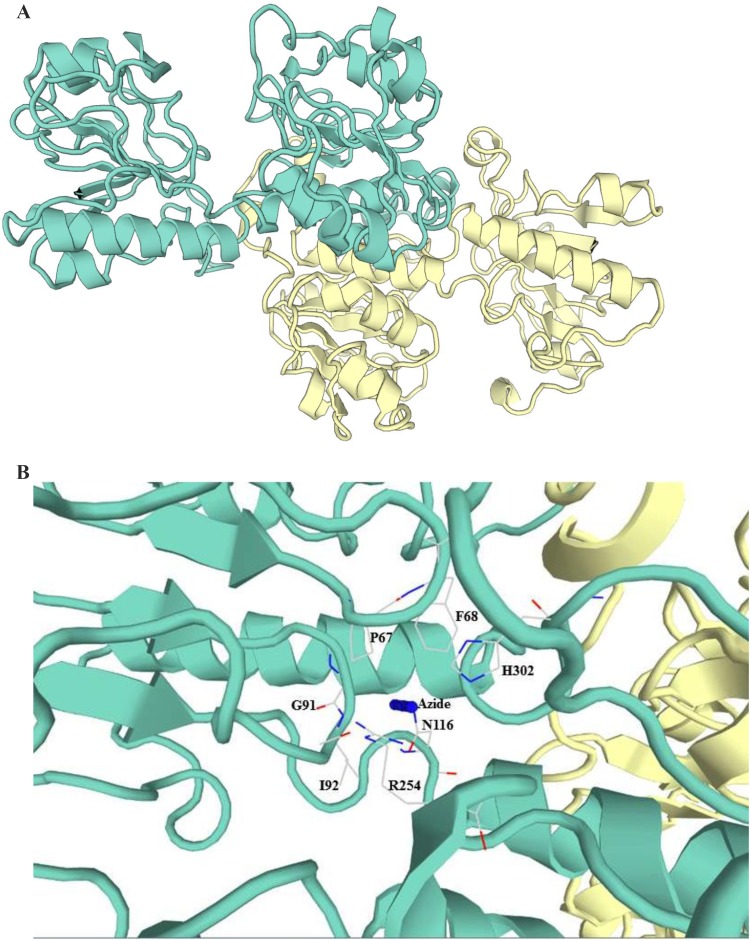

The 3D structure of recombinant GhFDH1 was modeled with SWISS-MODEL homology modeling tool using the apo-form of NAD-dependent Arabidopsis thaliana (AtFDH, pdb code: 3NAQ_A, resolution 1.70 Å) with 87.6% sequence identity to GhFDH, as template (Arnold et al. 2006). Global Model Quality Estimation score which is a quality estimation by combining properties from the target-template alignment, is 0.97 and QMEAN which stands for Qualitative Model Energy Analysis, value is 0.58 (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Homology model of truncated GhFDH1: apo-form of GhFDH1 constructed using AtFDH (pdb code: 3NAQ_A) as template (a). Important residues that are involved in substrate binding at the active site of GhFDH1 are shown on the model constructed using ligand bound AtFDH NAD+–azide ternary complex (pdb code: 3N7U) as template. Azide mimics the substrate (formate) in the transition state of the reaction (b)

Analysis of the truncated GhFDH1 3D-structure revealed that the critical residues in the substrate binding sites of the enzyme are Ile92 and Asn116 residues, whereas NAD+ binding sites are Asp191, Asn252 and Asp278 amino acids. As reported by earlier studies, Arg254 and His302 are important residues for the catalytic activity of the enzyme (Arnold et al. 2006; Labrou et al. 2001). Arg254 stabilizes the negative charge of the migrating hydride ion from formate to NAD+, while it destabilizes the positively charged NAD+. Steric and electrostatic properties of His302 make this residue important for catalytic function of the enzyme (Labrou et al. 2001). UniProtKB analysis also reported that the nucleotide binding regions of GhFDH1 are located on Arg171 and Ile172; Pro226 and Lys230 and also His301 and Gly305 residues (The UniProtConsortium 2017).

Furthermore, the 3D model (GMQE: 0.96, QMEAN: 0,84), constructed using A. thaliana FDH (pdb code: 3N7U, resolution 2.00 Å,) as template, showed that Pro67, Phe68, Gly91, Ile92, Asn116, Arg254 and His302 residues are important for ligand binding (Fig. 4b).

Conclusions

The lack of protein thermostability is a limiting factor for the development of biotechnological or industrial biotransformation processes. Because microbial-sourced FDH enzymes do not meet the expected stability during industrial synthesis and as the mutants obtained via protein engineering studies still need to be improved, plant-sourced FDHs are worthy of recombinant production and of being investigated as industrial biocatalysts.

The difference between the temperature response and thermal stability of homologous enzymes from different species is known to be directly related to the geographic climate temperature to which the organisms are adapted (Somero 1995). For instance, it is reported that activase enzyme isolated from hot climate plants such as cotton and tobacco, is more thermotolerant than activase from moderate climate plants such as spinach (Salvucci and Crafts-Brander 2004). Therefore, in the present study we characterized the catalytic efficiency, coenzyme specificity and thermal stability of FDH from cotton (GhFDH1), which needs higher temperatures, reaching to 35–40 °C, especially during the development period of the cones. The results obtained from this study showed that in addition to having thermostability higher than the recombinant FDHs isolated from some microorganisms, GhFDH1 has remarkable affinity to formate and NAD(P)+ among other FDHs reported before. In conclusion, even though further improvements are required, GhFDH1 is considered as a novel candidate for NAD(P)H regeneration and agronomic researches by its promising thermostability and NADP+ specificity.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK), Project No. 216Z052.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in the publication.

References

- Abdellaoui S, Chavez MS, Matanovic I, Stephens AR, Atanassov P, Minteer SD. Hybrid molecular/enzymatic catalytic cascade for complete electro-oxidation of glycerol using a promiscuous NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase from Candida boidinii. Chem Commun. 2017;53:5368–5371. doi: 10.1039/C7CC01027C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekseeva AA, Savin SS, Tishkov VI. NAD + -dependent formate dehydrogenase from plants. Acta Naturae. 2011;3:38–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekseeva AA, Serenko AA, Kargov IS, Thiskov VI. Engineering catalytic properties and thermal stability of plant formate dehydrogenase by single-point mutation. Prot Eng Des Sel. 2012;25:781–788. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzs084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekseeva AA, Fedorchuk VV, Zarubina SA, Sadykhov EG, Matorin AD, Savin SS, Tishkov VI. The role of Ala198 in the stability and coenzyme specificity of bacterial formate dehydrogenases. Acta Naturae. 2015;7:60–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alissandratos A, Kim HK, Matthews H, Hennessy JE, Philbrook A, Easton CJ. Clostridium carboxidivorans strain P7T recombinant formate dehydrogenase catalyzes reduction of CO2 to formate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:741–744. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02886-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altaş N, Aslan AS, Karataş E, Chronopoulou E, Labrou NE, Binay B. Heterologous production of extreme alkaline thermostable NAD + -dependent formate dehydrogenase with wide-range pH activity from Myceliophthora thermophila. Process Biochem. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Andreadeli A, Platis D, Tishkov V, Popov V, Labrou NE. Structure-guided alteration of coenzyme specificity of formate dehydrogenase by saturation mutagenesis to enable efficient utilization of NADP+ FEBS J. 2008;275:3859–3869. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreadeli A, Flemetakis E, Axarli I, Dimou M, Udvardi MK, Katinakis P, Labrou NE. Cloning and characterization of Lotus japonicus formate dehydrogenase: a possible correlation with hypoxia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794:976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bıçakçı E, Memon AR. An efficient and rapid in vitro regeneration system for metal resistant cotton. Biol Plant. 2005;49:415–417. doi: 10.1007/s10535-005-0018-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H, Joo JC, Cho DH, Kim MH, Lee SH, Jung KD, Kim YH, Yong HK (2014) Efficient CO2-reducing activity of NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase from Thiobacillus sp. KNK65MA for formate production from CO2 Gas. PLoS ONE 10.1371/journal.pone.0103111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- David P, des Francs-Small CC, Sévignac M. Thareau V, Macadré C, Langin T, Geffroy V (2010) Three highly similar formate dehydrogenase genes located in the vicinity of the B4 resistance gene cluster are differentially expressed under biotic and abiotic stresses in Phaseolus vulgaris. Theor Appl Genet. 121: 87–103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davies J, Clarke T, Butt J, Richardson D. Carbon fixation via the formate dehydrogenases of Shewanella. New Biotechnol. 2016;33:S110. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2016.06.1104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding HT, Liu DF, Li ZL, Du YQ, Xu XH, Zhao YH. Characterization of a thermally stable and organic solvent–adaptative NAD + -dependent formate dehydrogenase from Bacillus sp. F1. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;111:1075–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogal S, Beneventi E, Cendron L, Bergantino E. Structural basis for double cofactor specificity in a new formate dehydrogenase from the acidobacterium Granulicella mallensis MP5ACTX8. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:9541–9554. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6695-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igamberdiev AU, Bykova NV, Kleczkowski NA. Origins and metabolism of formate in higher plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1999;37:503–513. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(00)80102-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Junxian Z, Taowei Y, Junping Z, Xu M, Zhang X, Rao Z. Elimination of a free cysteine by creation of a disulfide bond increases the activity and stability of Candida boidinii formate dehydrogenase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1128/AEM.02624-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargov IS, Kleimenov SY, Savin SS, Tishkov VI, Alekseeva AA. Improvement of the soy formate dehydrogenase properties by rational design. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2015;28:171–178. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzv007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrou NE, Rigden DJ. Active-site characterization of Candida boidinii formate dehydrogenase. Biochem. J. 2001;354:455–463. doi: 10.1042/bj3540455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Fan G, Lu C, Xiao G. Genome sequence of cultivated upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum TM-1) provides insights into genome evolution. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:524–530. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou HQ, Gong YL, Fan W, Xu JM, Liu Y, Cao MJ, Wang MH, Yang JL, Zheng SJ. Rice bean VuFDH functions as formate dehydrogenase that confers tolerance to aluminum and low pH. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:294–305. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanba H, Takaoka Y, Hasegawa J. Purification and characterization of an α-haloketone-resistant formate dehydrogenase from Thiobacillus sp. strain KNK65MA, and cloning of the gene. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:2145–2153. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niks D, Duvvuru J, Escalona M, Hille R. Spectroscopic and kinetic properties of the molybdenum-containing, NAD(+)—dependent formate dehydrogenase from Ralstonia eutropha. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:1162–1174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.688457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson BJS, Skavdahl M, Ramberg H, Markwell J. FDH in Arabidopsis thaliana: characterization and possible targeting to the chloroplast. Plant Sci. 2000;159:205–212. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00337-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordu EB, Karaguler NG. Improving the purification of NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenase from Candida methylica. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2007;37:333–341. doi: 10.1080/10826060701593233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordu EB, Sessions RB, Clarke AR, Karaguler NG. Effect of surface electrostatic interactions on the stability and folding of formate dehydrogenase from Candida methylica. J Mol Catal B-Enzymatic. 2013;95:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2013.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Özgün G, Karagüler NG, Turunen O, Turner NJ, Binay B. Characterization of a new acidic NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenase from thermophilic fungus Chaetomium thermophilum. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2015;122:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2015.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos JS, Agarwala R. COBALT: constraint-based alignment tool for multiple protein sequences. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1073–1079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert X, Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucl: Acids Res; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadykhov EG, Soinova NS, Uglanova SV, Petrov AS, Thiskov VI. Comparable study of thermal study of FDHs from microorganisms and plants. Applied, Biocem Microbiol. 2006;42:236–240. doi: 10.1134/S0003683806030021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salvucci ME, Crafts-Brandner SJ. Relationship between the heat tolerance of photosynthesis and the thermal stability of rubisco activase in plants from contrasting thermal environments. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1460–1470. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.038323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalin IG, Serov AE, Skirgello OE, Timofeev VI, Samygina VR, Popov VO, Tishkov VI, Kuranova IP. Recombinant formate dehydrogenase from Arabidopsis thaliana: preparation, crystal growth in microgravity, and preliminary X-ray diffraction study. Crystallogr Rep. 2010;55:806–810. doi: 10.1134/S1063774510050159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi T, Fukusaki E, Kobayashi A. Formate dehydrogenase in rice plant: growth stimulation effect of formate in rice plant. J Biosci Bioeng. 2000;89:241–246. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(00)88826-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somero GN. Proteins and temperature. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:43–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sungrye K, Min Koo K, Sang Hyun L, Yoon S, Jung KD. Conversion of CO2 to formate in an electroenzymatic cell using Candida boidinii formate dehydrogenase. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B-Enzymatic. 2014;102:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2014.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:158–169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishkov VI, Uglanova SV, Fedorchuk VV, Savin SS. Influence of ıon strength and pH on thermal stability of yeast formate dehydrogenase. Acta Naturae. 2010;2:82–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishkov VI, Goncharenko KV, Alekseeva AA, Kleymenov SY, Savin SS. Role of a structurally equivalent phenylalanine residue in catalysis and thermal stability of formate dehydrogenases from different sources. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2015;80:1690–1700. doi: 10.1134/S0006297915130052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You C, Huang R, Wei X, Zhu Z, Zhang YP. Protein engineering of oxidoreductases utilizing nicotinamide-based coenzymes, with applications in synthetic biology. Synthetic Syst Biotechnol. 2017;2:208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Niks D, Mulchandani A, Hile R. Efficient reduction of CO2 by the molybdenum-containing formate dehydrogenase from Cupriavidus necator (Ralstonia eutropha) J Biol Chem. 2017;292:16872–16879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.785576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Ding Q, Zeng J, Wang FR, Zhang J, Fan SJ, He XQ. An improved CTAB-ammonium acetate method for total RNA isolation from cotton. Phytochem Anal. 2012;23:647–650. doi: 10.1002/pca.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]