Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

Previous studies have evaluated quality of life (QoL) in patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) for cholelithiasis. The purpose of this study was to evaluate QoL after index admission LC in patients diagnosed with acute cholecystitis (AC) using the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) questionnaire.

Methods

Patients ≥21 years admitted to Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore for AC and who underwent index admission LC between February 2015 and January 2016 were evaluated using the GIQLI questionnaire preoperatively and 30 days postoperatively.

Results

A total of 51 patients (26 males, 25 females) with a mean age of 60 years (24–86 years) were included. Median duration of abdominal pain at presentation was 2 days (1–21 days). 45% of patients had existing comorbidities, with diabetes mellitus being most common (33%). 31% were classified as mild AC, 59% as moderate and 10% as severe AC according to Tokyo Guideline 2013 (TG13) criteria. Post-operative complications were observed in 8 patients, including retained common bile duct stone (n=1), wound infection (n=2), bile leakage (n=2), intra-abdominal collection (n=1) and atrial fibrillation (n=2). 86% patients were well at 30 days follow-up and were discharged. A significant improvement in GIQLI score was observed postoperatively, with mean total GIQLI score increasing from 106.0±16.9 (101.7–112.1) to 120.4±18.0 (114.8–125.9) (p<0.001). Significant improvements were also observed in GIQLI subgroups of gastrointestinal symptoms, physical status, emotional status and social function status.

Conclusions

Index admission LC restores QoL in patients with AC as measured by GIQLI questionnaire.

Keywords: Acute cholecystitis, Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI), Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Acute cholecystitis (AC) is a common surgical condition. Index admission laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) up to 5 days from the onset of symptoms is the gold standard of care for mild to moderate AC.1,2 Index admission LC is safe, reduces overall length of hospital stay and reduces readmissions due to recurrent biliary events.2 Actual healthcare costs are decreased in patients who undergo index admission LC compared to those who undergo interval LC for AC.3

Quality-of-life (QoL) is influenced by health and healthcare interventions, and is an important end point in clinical trials for chronic illness and malignancy.4 Pain, both acute and chronic, is one of the main factors that negatively impacts QoL.5 Psychosocial, function and emotional dimensions of QoL are equally important but have been poorly studied and reported in acute care surgery. It is possible that an uncomplicated surgery may improve the pain-related short-term QoL outcomes; however effect of acute surgery on overall QoL cannot be assumed to be positively influenced by surgery. Hence, it is important to prospectively study the effects of urgent surgical treatment on QoL outcomes. The Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI)6 is one of the most widely used questionnaires for objective measurement of QoL in gastrointestinal surgery. It was first validated in LC in 1993,6 and has ever since been increasingly used for various other conditions. First developed in German and English,7 Spanish,8 Swedish9 and Chinese10 versions have subsequently been validated.

Previous studies have implemented the GIQLI score in evaluating QoL following elective LC for symptomatic10,11,12,13 and non-symptomatic cholelithiasis,8,9,12,13,14,15,16,17 chronic acalculous cholecystitis,18 laparoscopic versus open approach for cholecystectomy,15,19 factors predicting QoL benefits following LC,20,21,22,23 the appropriateness of LC24 and QoL difference between post-LC patient and the background population.25 However, no study to date has addressed whether index admission LC improves/restores QoL in AC. The present study was done to evaluate, quantify and determine whether index admission LC restores QoL in adult patients with AC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient inclusion criteria

This is a single center, prospective study. All adult patients (≥21 years on admission) with AC admitted under the hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) team at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore from February 2015 to January 2016 were included. The diagnosis and severity of AC was classified according to Tokyo Guidelines 2013 (TG13) diagnostic criteria.26 Patients unable to consent due to pre-existing mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia, dementia) were excluded. One patient with a contiguous liver abscess due to perforated cholecystitis was included in this study. Patients with AC and concomitant common bile duct stones were managed with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) and stone retrieval prior to LC and were included in the study.

This study is conducted by the HPB team of surgeons who practice index admission LC. We have adopted a policy of “universal cholecystectomy”, meaning that any surgically fit patient with an indication for cholecystectomy is unconditionally offered index admission LC, irrespective of the duration of symptoms. The patient is given the option to decline surgery at index admission if he/she so wishes. Universal cholecystectomy encompasses a wide range of indications including all grades of AC, mild to moderate cholangitis after biliary stone clearance and patients with mild to moderate acute biliary pancreatitis. A liberal use of ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography (MRCP) imaging aids in early and prompt decision making.

This study was not funded and was conducted with existing team resources. Because of this, it was deliberately truncated after 12 months.

Data collection

Junior doctors attached to the HPB team assisted in prospective data collection and ensuring adequacy and completion of the GIQLI questionnaire. Demographic and clinical data, including comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index and the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) score were collected. Blood investigation results, laboratory findings and imaging results were compiled. We recorded TG13 severity classification, operative records (surgical access, operation duration, intra- operative blood loss, and drain insertion), length of hospital stay, morbidity, mortality and readmission details. Length of hospital stay was defined from date of admission to discharge. Readmission was defined as readmission to hospital within 30 days after operation, irrespective of whether the issue on readmission was directly, indirectly or unrelated to the surgical procedure. Mortality was defined as death within 30 days of operation or during the current admission.

Operational data for best practice and audit purpose including pre-operative emergency department admission to operation time, post-operation to discharge time and hospitalization costs were analyzed.

GIQLI

GIQLI is a 36-question survey, with five response levels to each survey question (0–4, a higher value represents a better outcome). The questionnaire records the health status of a patient over the past two weeks and records the response as “all the time, most of the time, some of the time, a little of the time or never”. The data is then subcategorized into four subgroups: gastrointestinal symptoms (19 questions, total score 0–76), physical status (7 questions, total score 0–28), emotional status (5 questions, total score 0–20) and social function status (5 questions, total score 0–20). The questionnaire was administered pre-operatively at the time of consent. The default method of administration was self-administration, while interviewer-assisted administration was performed for patients who were illiterate or suffering from visual impairment. It is our routine clinical practice to follow-up all LC patients in the outpatient setting at 30-day post-operation and hence the post-operation questionnaire was administered in the same setting. The physician providing the questionnaire checked for completeness of all domains. No further patient contact was done.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 7.0 software. Paired t-test was used to compare pre-operative and post-operative total GIQLI scores, as well as subgroup analysis, with a p-value of <0.05 accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients

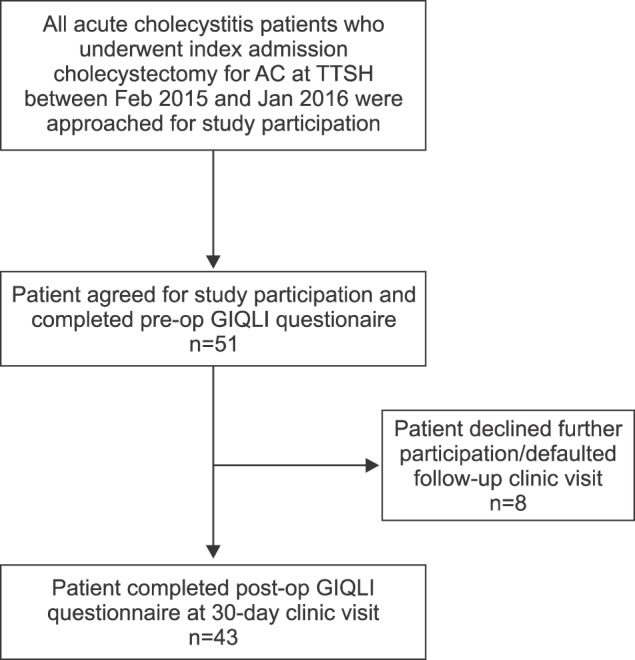

A total of 51 patients who met the inclusion criteria were agreeable for participation in our study pre-operatively and completed the pre-operative GIQLI questionnaire. Subsequently, eight patients declined continued participation or defaulted outpatient clinic follow-up. A total of 43 cases with complete pre-operative and post-operative GIQLI data were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Patient inclusion flowchart. AC, acute cholecystitis; TTSH, Tan Tock Seng Hospital.

Demographic and clinical profile

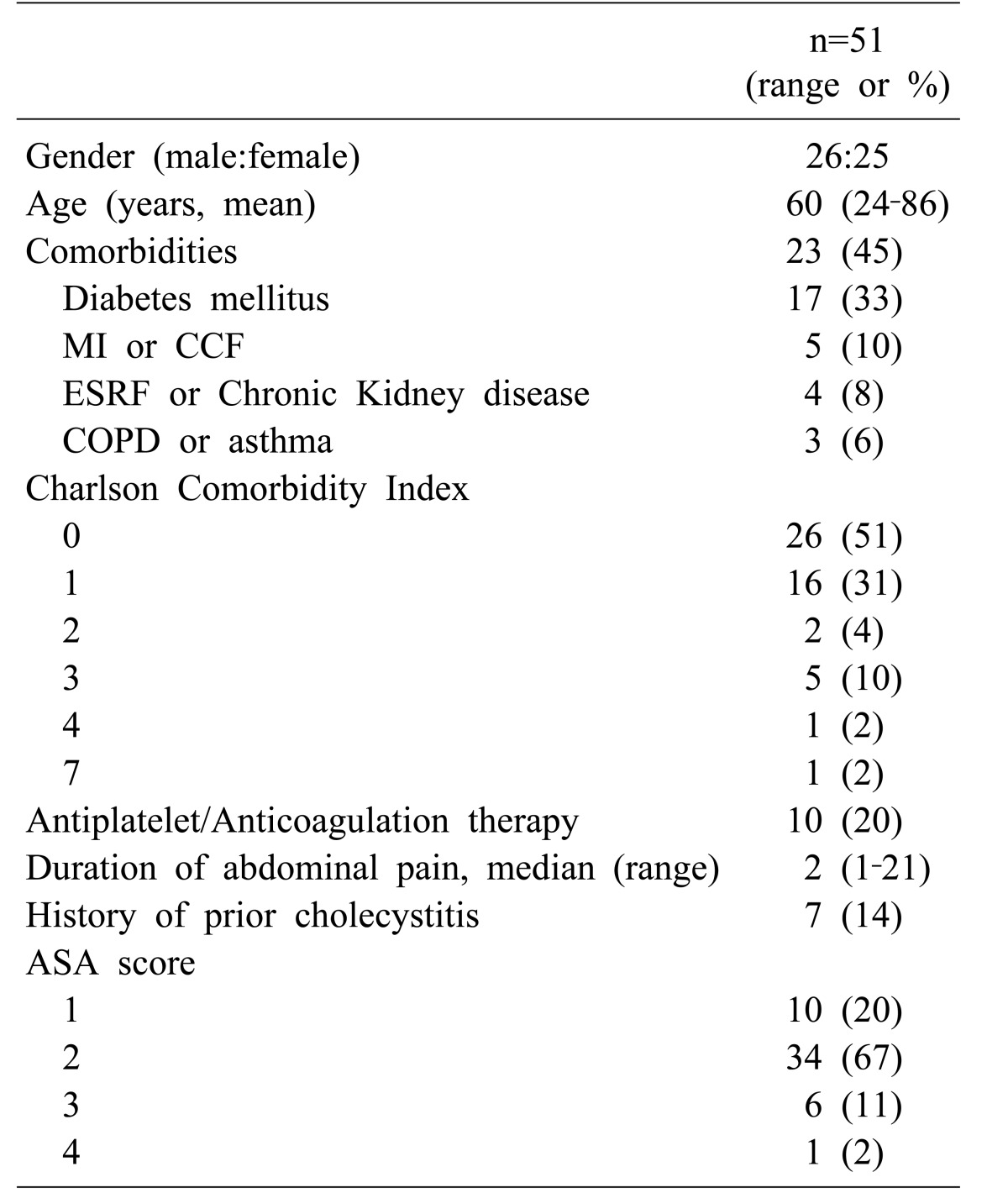

Demographic and clinical data of the 51 patients are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 60 (range: 24–86) years, with equivalent men and women (26 men, 25 women). Ten of 51 (20%) patients were ASA grade 1, 67% (34/51) were ASA grade 2, 11% (6/51) were ASA grade 3 and 2% (1/51) were ASA grade 4. With regards to the Charlson Comorbidity Index, 51% (26/51) scored 0, representing a previously healthy individual with no significant comorbidity of note, 31% (16/51) scored 1 and 4% (1/51) scored 2, representing mild comorbidity severity, while 10% (5/51) scored 3 and 2% (1/51) scored 4, representing moderate comorbidity severity. One patient scored 7 indicative of severe comorbidity; the patient had a complicated and prolonged hospital/intensive care unit stay. Among all patients, diabetes was the most common comorbidity (17/51, 33%). Median duration of abdominal pain on presentation was 2 days (1–21 days). Seven patients (14%) had previous episodes of AC. Abdominal tenderness; abdominal lump and guarding are time and treatment sensitive clinical variables with inter-observer variation and though clinically documented, are not reported.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical profile.

MI, myocardial infarction; CCF, congestive cardiac failure; ESRF, end-stage renal failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidential interval; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists

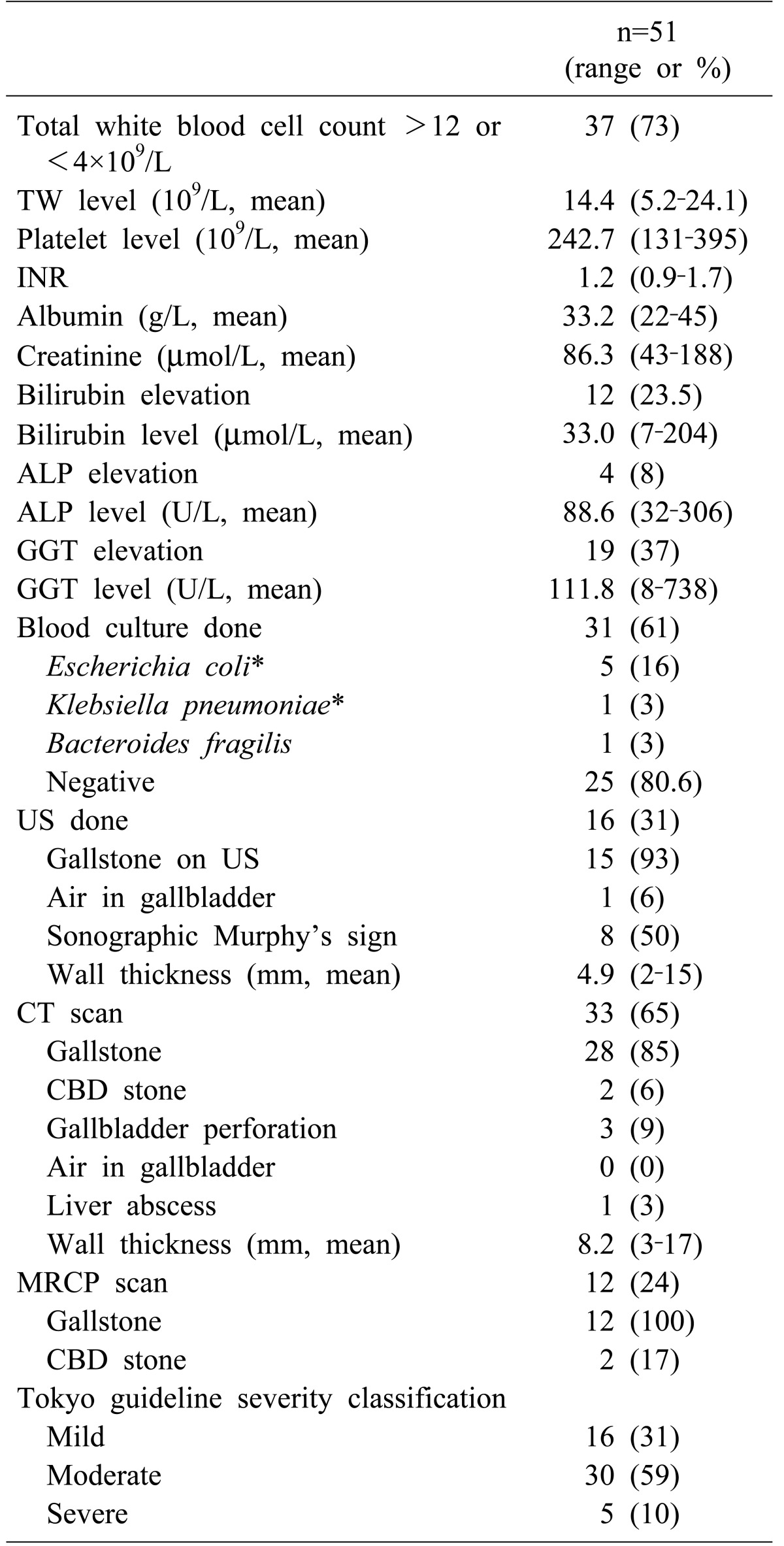

Laboratory and radiological data is shown in Table 2. Significant total white blood cell (TW) changes defined as >12 or <4×109/L were observed in 73% (37/51) patients. Blood culture was taken in 61% (31/51) of patients, with four patients growing Escherichia coli, with one patient growing both E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, one patient growing Bacteroides fragilis and no growth in the remaining 25 (80.6%) patients. Computed tomography (CT) scan was the most common radiological investigation performed (65%), followed by ultrasonography (31%) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) imaging (24%). According to TG13, 31% were classified as mild AC, 59% as moderate AC and 10% as severe AC.

Table 2. Laboratory and radiological findings.

TW, total white blood cell count; INR, international normalized ratio; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; US, ultrasonography; CT, computed tomography; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; CBD, common bile duct

*One case grew both Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in blood culture

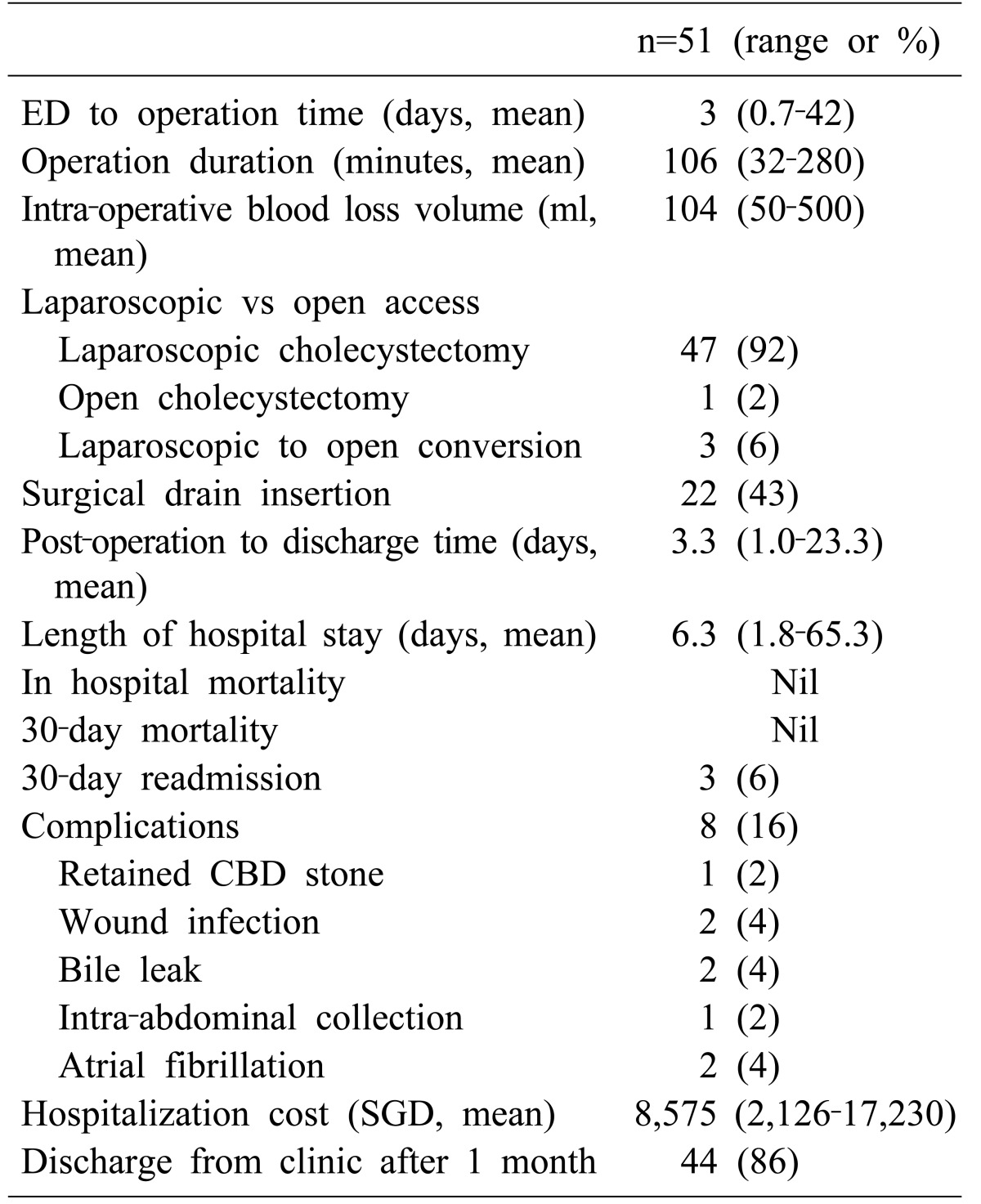

Most (92%) patients had successful LC. One patient had upfront open cholecystectomy and three laparoscopic-to-open conversions were performed due to technical difficulties in dissecting the Calot's triangle and delineating the biliary anatomy. Mean operative duration was 106 min (range: 32–280 min). Surgical drain was inserted in 43% of cases. Post-operative complications were observed in eight patients: one patient had retained common bile duct (CBD) stone, 2 patients had umbilical port site infection, 2 patients had postoperative bile leak, one patient had intra-abdominal collection and 2 patients had atrial fibrillation. In the patient with a retained CBD stone, ERCP was successfully done. The 2 patients with umbilical port site wound infection were managed with oral antibiotics. Two patients with bile leak were managed with observation as it was low volume and both resolved spontaneously. The patient with intra-abdominal collection was readmitted on post-operation day six with abdominal pain. A CT scan showed 3 cm intra-abdominal collection; he was treated with antibiotics and made an uneventful recovery. Many (86%) of patients were well with no complaints at the 30-day clinic visit and were discharged from our service. There was no mortality. Surgical and operational data are reported in Table 3. Mean pre-operative Emergency Department admission to operation was 3 days, while mean post-operation length of hospital stay was 3 days. The average cost of hospital stay was Singapore dollars (SGD) $8,575 ($2,126–$17,230).

Table 3. Surgical outcomes.

ED, Emergency department; SGD, Singapore dollars; POD, Post-Operation Day; CBD, Common bile duct

QoL assessment with the GIQLI questionnaire

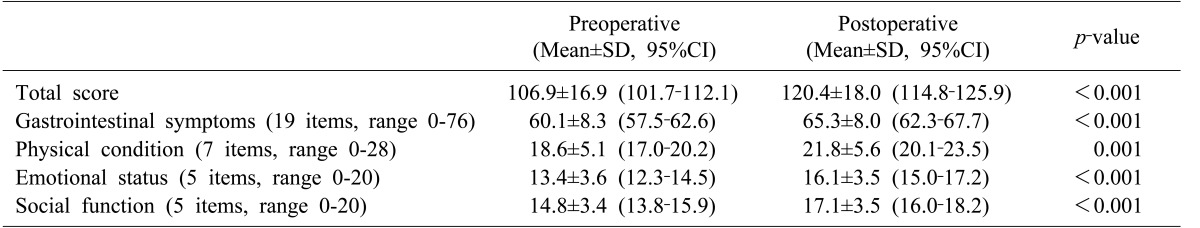

Fifty one patients completed the pre-operative GIQLI questionnaire and 43 completed the post-operative GIQLI questionnaire. Three patients with readmission had their clinic appointments rescheduled and did not complete the 1-month GIQLI questionnaire. One patient did not come for post-operative follow-up and four patients declined to complete the GIQLI questionnaire due to time constraints in outpatient clinic. In order to perform paired t-test analysis, only the data obtained from patients who completed both the pre-operative and post-operative GIQLI questionnaires was used. Table 4 summarizes pre-operative and post-operative GIQLI scores as well as paired t-test results.

Table 4. Preoperative and postoperative GIQLI score.

GIQLI, Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidential interval

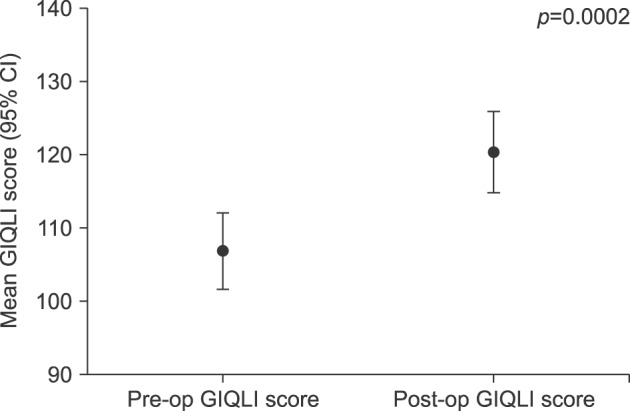

Of a total score of 144, mean pre-operative total GIQLI score was 106±16.9 (95% CI, 101.7–112.1), while post-operative total GIQLI score was 120.4±18.0 (95% CI, 114.8–125.9, p<0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Comparison of Pre-operative and Post-operative total GIQLI score. Pre-op, pre-operative; Post-op, post-operative; GIQLI, Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index.

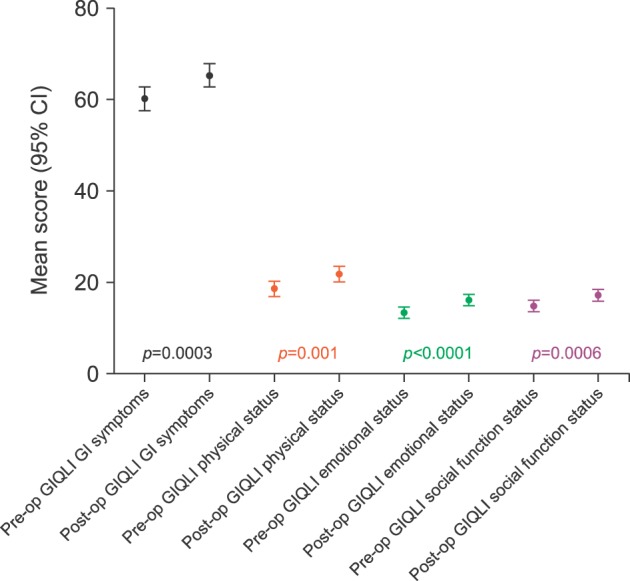

The GIQLI questionnaire can be subdivided into four categories: gastrointestinal symptoms, physical condition, emotional status and social function. Pre-operative mean gastrointestinal symptoms score was 60.1±8.3 (95% CI, 57.5–62.6), while post-operative mean gastrointestinal symptoms score was 65.3±8.0 (95% CI, 62.3–67.7, p<0.001). Similarly, statistically significant improvements were observed in the domains of physical condition, emotional status and social function (Table 4 and Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Subgroup comparisons of pre-operative and post-operative GIQLI score. Pre-op, pre-operative; Post-op, post-operative; GIQLI, Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index.

DISCUSSION

This is a prospective pre-and-post intervention QoL study in AC patients treated with index admission cholecystectomy. We demonstrated that QoL was restored at 30-day after index admission LC for AC. This restoration of QoL was observed individually in each of the four sub-domains of GIQLI questionnaire.

An ideal study design would compare QoL changes in AC patients managed by index admission LC and interval LC. However, in view of the established benefits of index admission LC, such a study would not be ethical. Furthermore, such comparison is of limited value due to multiple confounding factors, such as variable symptom duration, different patient cohorts with varying severity of AC and comorbidities, need for percutaneous cholecystostomy for severe AC as well as the duration to cholecystectomy. Patients who are not deemed suitable for index admission LC have existing comorbidities that preclude fitness for surgery, and as such require further work-up and optimization prior to surgery. Including this group of patients in the study would introduce a selection bias. Based on the available evidence, our hypothesis was that index admission LC would restore QoL and patient managed conservatively have potential that QoL may worsen if further complications ensue. It is possible that conservative management could restore QoL of AC patients. However, as our unit has a policy of index admission LC, we could not conduct a study to include this group. Hence a single arm prospective study was conducted.

One prior study included patients who underwent LC for AC in QoL analysis.27 Of 451 patients with various gallstones related diseases, 107 patients had cholecystectomy for AC or previous AC. They studied long-term QoL benefits from surgery and concluded that indication for LC together with gender was able to predict gastrointestinal symptoms after LC. Interestingly, 33.6% of patients with AC were treated with open cholecystectomy, which is not our experience. Furthermore, patients with index admission and interval cholecystectomy were analyzed together. Hence QoL restoration following index admission surgery remained to be established. We studied the short-term QoL outcome at 1 month as this is the earliest time for planned interval cholecystectomy. Also, it is routine practice to review patients at 1 month in the outpatient clinic and discharge if recovered. Further, it is highly unlikely if QoL was restored at 1 month it would worsen later unless interim complications occur. In our series, all complications revealed within 1 month.

We have shown that index admission LC restores QoL at 1 month. This is important in the acute setting as AC is associated with worse QoL compared to symptomatic cholelithiasis. Our study reports higher post-operative GIQLI scores and more significant improvement in QoL compared to a prior study.15 Mean improvement in pre-operative to post-operative total GIQLI score in our study was 13.5 points, whereas in the prior study an increase of 6.4 points at 5 weeks was reported in patients treated with elective LC for cholelithiasis/chronic cholecystitis.15 Thus, the magnitude of improvement of QoL is proportional to its worsening.11,12,28

QoL is a multi-dimensional tool and is not restricted to presence and severity of clinical symptoms alone. Hence it would be inaccurate to assume that index admission surgery would improve QoL in patients with AC. A systematic review including 38 studies and 9,903 patients reported that upper abdominal pain persisted in 33% of patients after cholecystectomy and a new onset de novo abdominal pain occurred in 14% of patients.29 The authors concluded that cholecystectomy is often ineffective with regards to symptoms. However, this review mostly included low quality studies, 26 studies with self-administered questionnaire, 15 studies with open cholecystectomy and variable follow up duration and hence the results should be interpreted with caution. Procedure related morbidity affects short term QoL negatively.4 In our study, severe morbidity was low and hence likely contributed to improved QoL outcomes. Furthermore, in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis, persistent abdominal pain is the most common reason for unsuccessful outcomes and in the acute setting, immediate pain relief is achieved by surgery and could have contributed to improve QoL.30 However, even the emotional status, social function and physical scores showed improvements. So, the benefits of index admission surgery cannot be attributed solely to improvement of abdominal symptoms. Further, GIQLI questionnaire has only one item on abdominal pain and hence overall impact of improvement in abdominal pain due to index admission surgery is unlikely to influence the GIQLI abdominal symptom score.

Index admission cholecystectomy has been established as a standard of care in patients with AC.31 TG13 recommends early cholecystectomy in mild and certain moderate AC.1 We have previously reported that TG13 can be restrictive and patients with moderate or severe AC can also be safely treated with index admission cholecystectomy.32 In our current study also more than two thirds of patients had moderate or severe AC. A Cochrane review reporting on six clinical trials including 488 patients with AC and comparing index admission LC with interval LC concluded that index admission LC does not positively influence bile duct injury, serious complications and conversion to open cholecystectomy.31 None of the trials studied QoL outcomes and the only benefit observed was in reduction in length of hospital stay. Reduced hospital stay directly benefits healthcare system and would only benefit patients if this translated to earlier return to work. Only one trial including 36 patients reported that index LC is associated with earlier return to work.33 In local practice, all patients with LC are provided with 14 days of hospitalization leave regardless of index or interval surgery. Furthermore, Gurusamy et al.31 reported that 18.3% of patients developed recurrent biliary event requiring emergency surgery with on open conversion rate of 45%. It is likely that QoL of these patients would be worse. QoL outcomes are the only potential outcomes that directly impact patient and hence earlier restoration of QoL is an important element of good clinical practice. Our study establishes that QoL can be restored by index admission cholecystectomy and benefits of index surgery are not restricted to financial gains but also directly reaped by patients.

The strength of our study is that it is the first prospective study to quantify QoL improvement in AC patients treated with index admission LC. It has a representative group of patients with differing severities of AC and spectrum of comorbidities.

Single center and small sample are the limitations of our study. It is possible that patients with severe comorbidity profile were not offered index admission surgery, so the results are not valid for patients treated with interval cholecystectomy. However, earlier restoration of QoL was observed and adds supporting evidence of benefits of index admission surgery. Eight patients did not complete the GIQLI questionnaire and it is possible that their QoL was possibly worse due to readmission or morbidity. However, five patients declined GIQLI questionnaire not due to morbidity but due to time constraints. This study was not funded and with existing team resources, 84.3% patients had both the pre and post-operative GIQLI questionnaires completed. This is comparable to a response rate of 80.9% at 12 weeks in a prospective study of 423 patients with symptomatic gallstones.11 The GIQLI questionnaire requries time to complete. The use of a more simplified QoL tool or web-based online survey might increase patient participation. However, the mean age of our patients was 60 years and web-based tools would not have reduced the dropout rates significantly, given that web participation of this age group is typically not as extensive as with younger people. Multiple measurements and measurement at longer duration than 1 month would have provided more information to our study. However, in local setting interval cholecystectomy is offered 4–6 weeks after the previous episode of AC. Thus, we decided to conduct the post-treatment QoL survey at 30 days. This was consistent with the scheduled planned post-operative follow-up visits and was feasible with existing team resources. Furthermore, delaying the QoL survey any longer would introduce bias by development of de novo symptoms, which could negatively influence QoL. Lastly, statistical significant improvement in QoL measurement may not be clinically relevant and it is important to quantify the tangible benefits to the patient.

In conclusion, our study is the first to demonstrate that index admission cholecystectomy restores QoL in patients with AC as measured by GIQLI score. Patients with all grades of severity of AC enjoy the QoL restoration and benefits of index admission cholecystectomy are directly reaped by the patient.

References

- 1.Miura F, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Pitt HA, Gouma DJ, et al. TG13 flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:47–54. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0563-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansaloni L, Pisano M, Coccolini F, Peitzmann AB, Fingerhut A, Catena F, et al. 2016 WSES guidelines on acute calculous cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2016;11:25. doi: 10.1186/s13017-016-0082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan CH, Pang TC, Woon WW, Low JK, Junnarkar SP. Analysis of actual healthcare costs of early versus interval cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:237–243. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed S, de Souza NN, Qiao W, Kasai M, Keem LJ, Shelat VG. Quality of life in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with transarterial chemoembolization. HPB Surg. 2016;2016:6120143. doi: 10.1155/2016/6120143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shelat VG, Eileen S, John L, Teo LT, Vijayan A, Chiu MT. Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life following a traumatic rib fracture. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2012;38:451–455. doi: 10.1007/s00068-012-0186-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eypasch E, Wood-Dauphinée S, Williams JI, Ure B, Neugebauer E, Troidl H. The Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index. A clinical index for measuring patient status in gastroenterologic surgery. Chirurg. 1993;64:264–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmülling C, Neugebauer E, et al. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg. 1995;82:216–222. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quintana JM, Cabriada J, López de, Varona M, Oribe V, Barrios B, et al. Translation and validation of the gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2001;93:693–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandblom G, Videhult P, Karlson BM, Wollert S, Ljungdahl M, Darkahi B, et al. Validation of Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index in Swedish for assessing the impact of gallstones on health-related quality of life. Value Health. 2009;12:181–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lien HH, Huang CC, Wang PC, Chen YH, Huang CS, Lin TL, et al. Validation assessment of the Chinese (Taiwan) version of the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index for patients with symptomatic gallstone disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:429–434. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamberts MP, Den Oudsten BL, Keus F, De Vries J, van Laarhoven CJ, Westert GP, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of symptomatic cholelithiasis patients following cholecystectomy after at least 5 years of follow-up: a long-term prospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:3443–3450. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3619-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamberts MP, Den Oudsten BL, Gerritsen JJ, Roukema JA, Westert GP, Drenth JP, et al. Prospective multicentre cohort study of patient-reported outcomes after cholecystectomy for uncomplicated symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1402–1409. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mentes BB, Akin M, Irkörücü O, Tatlicioğlu E, Ferahköşe Z, Yildinm A, et al. Gastrointestinal quality of life in patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic cholelithiasis before and after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1267–1272. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksen JR, Kristiansen VB, Hjortsø NC, Rosenberg J, Bisgaard T. Effect of laparoscopic cholecystectomy on the quality of life of patients with uncomplicated socially disabling gallstone disease. Ugeskr Laeger. 2005;167:2654–2656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Tao SF, Xu Y, Fang F, Peng SY. Patients' quality of life after laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2005;6:678–681. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2005.B0678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finan KR, Leeth RR, Whitley BM, Klapow JC, Hawn MT. Improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life after cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi HY, Lee KT, Lee HH, Uen YH, Chiu CC. Response shift effect on gastrointestinal quality of life index after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:335–341. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9760-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Planells Roig M, Bueno Lledó J, Sanahuja Santafé A, García Espinosa R. Quality of life (GIQLI) and laparoscopic cholecystectomy usefulness in patients with gallbladder dysfunction or chronic non-lithiasic biliary pain (chronic acalculous cholecystitis) Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2004;96:442–446. 446–451. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082004000700002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quintana JM, Cabriada J, Aróstegui I, López de, Bilbao A. Quality-of-life outcomes with laparoscopic vs open cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1129–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quintana JM, Arostegui I, Oribe V, López de, Barrios B, Garay I. Influence of age and gender on quality-of-life outcomes after cholecystectomy. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:815–825. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1259-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quintana JM, Aróstegui I, Cabriada J, López de, Perdigo L. Predictors of improvement in health-related quality of life in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1549–1555. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi HY, Lee HH, Tsai JT, Ho WH, Chen CF, Lee KT, et al. Comparisons of prediction models of quality of life after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a longitudinal prospective study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamberts MP, Kievit W, Gerritsen JJ, Roukema JA, Westert GP, Drenth JP, et al. Episodic abdominal pain characteristics are not associated with clinically relevant improvement of health status after cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1350–1358. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3156-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quintana JM, Cabriada J, Aróstegui I, Oribe V, Perdigo L, Varona M, et al. Health-related quality of life and appropriateness of cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2005;241:110–118. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000149302.32675.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wanjura V, Sandblom G. How do quality-of-life and gastrointestinal symptoms differ between post-cholecystectomy patients and the background population. World J Surg. 2016;40:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokoe M, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Mayumi T, Gomi H, et al. TG13 diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:35–46. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0568-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wanjura V, Lundström P, Osterberg J, Rasmussen I, Karlson BM, Sandblom G. Gastrointestinal quality-of-life after cholecystectomy: indication predicts gastrointestinal symptoms and abdominal pain. World J Surg. 2014;38:3075–3081. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2736-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lien HH, Huang CC, Wang PC, Huang CS, Chen YH, Lin TL, et al. Changes in quality-of-life following laparoscopic cholecystectomy in adult patients with cholelithiasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:126–130. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamberts MP, Lugtenberg M, Rovers MM, Roukema AJ, Drenth JP, Westert GP, et al. Persistent and de novo symptoms after cholecystectomy: a systematic review of cholecystectomy effectiveness. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:709–718. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinert CR, Arnett D, Jacobs D, Jr, Kane RL. Relationship between persistence of abdominal symptoms and successful outcome after cholecystectomy. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:989–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.7.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurusamy KS, Davidson C, Gluud C, Davidson BR. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for people with acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD005440. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005440.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amirthalingam V, Low JK, Woon W, Shelat V. Tokyo Guidelines 2013 may be too restrictive and patients with moderate and severe acute cholecystitis can be managed by early cholecystectomy too. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2892–2900. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, Lai EC, Wong J. Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1998;227:461–467. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]