Abstract

African HIV serodiscordant couples often desire pregnancy, despite sexual HIV transmission risk during pregnancy attempts. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduce HIV risk and can be leveraged for safer conception but how well these strategies are used for safer conception is not known. We conducted an open-label demonstration project of the integrated delivery of PrEP and ART among 1,013 HIV serodiscordant couples from Kenya and Uganda followed quarterly for 2 years. We evaluated fertility intentions, pregnancy incidence, the use of PrEP and ART during peri-conception, and peri-conception HIV incidence. At enrollment, 80% of couples indicated a desire for more children. Pregnancy incidence rates were 18.5 and 18.7 per 100 person years among HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected women, and higher among women who recently reported fertility intention (adjusted odds ratio=3.43, 95% CI 2.38-4.93) in multivariable GEE models. During the 6 months preceding pregnancy, 82.9% of couples used PrEP or ART and there were no HIV seroconversions. In this cohort with high pregnancy rates, integrated PrEP and ART was readily used by HIV serodiscordant couples, including during peri-conception periods. Widespread scale-up of safer conception counseling and services is warranted to respond to strong desires for pregnancy among HIV-affected men and women.

Keywords: Discordant couples, safer conception, PrEP, ART, pregnancy, Africa

Background

For HIV serodiscordant couples in which one partner is living with HIV and one partner is HIV-uninfected, pregnancy attempts may be accompanied by sexual and perinatal HIV transmission risk. Many studies among HIV serodiscordant couples have demonstrated that knowledge of HIV serodiscordancy does not change desires for pregnancy and these desires often outweigh fears of HIV transmission (1,2). Multiple strategies that are compatible with fertility desires exist to greatly reduce HIV transmission risk. Recent public health efforts utilize a harm reduction framework to encourage “safer conception” to minimize the risk of sexual transmission during pregnancy attempts. Safer conception strategies include antiretroviral therapy (ART) to suppress HIV viremia in the partner living with HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to protect the HIV uninfected partner, reserving condomless sex for days with peak fertility, medical male circumcision, self-insemination, and diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STI) (3). Interventions to optimize fertility and reduce the number of condomless sex acts, such as ovulation prediction, fertility screening, fertility treatment, and medically assisted reproduction, are also available in some settings and can be used when in line with couple and individual values and preferences (3,4).

HIV prevention counseling offers opportunities to initiate discussion about reproductive plans and encourage the use of effective contraception or safer conception strategies based on individual or couple goals. For HIV serodiscordant couples considering medication-based prevention, an integrated approach with PrEP use limited to the time prior to ART-induced HIV viral suppression in the HIV-infected partner, can virtually eliminate sexual HIV transmission and can be used when pregnancy is desired (5,6). We recently conducted the Partners Demonstration Project, an open-label study of the integrated delivery of PrEP and ART among high-risk HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda. Within this study, we explored fertility intentions, pregnancy, and evaluated the use of PrEP and ART as peri-conception HIV risk reduction strategies.

Methods

The Partners Demonstration Project was an open-label study of the integrated delivery of PrEP and ART among mutually-disclosed high risk HIV serodiscordant couples recruited from four sites: Thika and Kisumu, Kenya and Kampala and Kabwohe, Uganda (6). From November 2012 to August 2014, we recruited couples at high risk of HIV transmission, using a validated scoring tool that prioritizes the inclusion of younger couples with few children (7). Additional eligibility criteria for HIV-uninfected participants included having normal renal function with estimated creatinine clearance >60mL/min and no Hepatitis B infection. Partners living with HIV had not yet initiated ART and had no history of being WHO stage 3 or 4. All participants were age ≥18 years. HIV-uninfected women were ineligible if pregnant because there were no guidelines at the time for initiating PrEP during pregnancy; women living with HIV could be pregnant at enrollment.

Both members of the couple were scheduled for study visits 4 weeks after enrollment, 12 weeks after enrollment, and quarterly thereafter up to 24 months. At each visit, participants received couples-based HIV prevention counseling (8) and couples were asked about their fertility desires and counseled about safer conception or contraception as appropriate. At all quarterly visits, HIV-uninfected participants were counseled and tested for HIV and received PrEP prescriptions and PrEP adherence counseling. Participants living with HIV were referred to receive ART following national guidelines, which initially required a CD4 count <350 cells/μL or symptomatically advanced HIV disease, either on-site or at a public health clinic of their choice. In 2014, Kenyan and Ugandan ART guidelines were expanded to recommend use for all persons with HIV-uninfected partners, regardless of clinical indications. PrEP was provided to HIV-uninfected participants prior to and for a limited time following ART initiation by their HIV-infected partner; specifically, PrEP discontinuation was encouraged once the partner living with HIV had used ART for at least 6 months, a sufficient duration to achieve HIV viral suppression in most individuals following ART initiation (9). However, PrEP was continued beyond 6 months of ART use based on clinician discretion, especially in cases with clearly unsuppressed virus, when the couple was attempting pregnancy, or if the HIV-uninfected partner had a new partner with unknown HIV or ART status. For couples reporting an immediate desire for pregnancy, safer conception counseling included discussion of all safer conception strategies, including the available safety data on PrEP and ART use during peri-conception and pregnancy, how to time condomless sex to days with peak fertility, and referrals were given for couples to see fertility care providers if they desired. The strategies primarily recommended for each couple were tailored to their situation and preferences.

Urine pregnancy testing was conducted for all women during the screening process and as clinically indicated (e.g. with missed menses) during follow up visits. STIs were managed syndromically. Participants living with HIV were monitored for CD4 count and viral load and HIV-uninfected participants were monitored for creatinine clearance every 6 months. Sexual behavior and fertility intentions were assessed via standardized interviewer-administered surveys at each quarterly visit. Fertility desires were assessed by asking, “How many more children would you like to have now or in the future?” and responses of ≥1 were followed by “When do you plan to have your next child?” to assess the desired timing of the next pregnancy. Pregnant women were asked in a sensitive manner if their pregnancy was intended.

Statistical methods

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the fertility intentions, pregnancy incidence, and use of PrEP and ART during the peri-conception period, defined as the 6-month period preceding pregnancy. Consistent PrEP use was defined based on pharmacy records of PrEP refills and ART use was defined by participant self-report. We calculated pregnancy incidence as the number of pregnancies per 100 person years when women were not pregnant. Data from women living with HIV who entered the study pregnant were censored until the completion of the pregnancy. The start date of a pregnancy was assigned to be the start date of the last menstrual period but if this was unknown, it was estimated based on the known pregnancy end date and duration of the gestation.

We used general estimating equations to determine the association between women's fertility intention (currently attempting pregnancy versus no intention or intention at a later time) and the occurrence of pregnancy at the next quarterly visit. A priori, we adjusted these models for age and use of effective contraception. We considered additional demographic, medical, and behavioral factors as potential confounders and maintained those that substantially changed the point estimate (by >10%) in final models. SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) and R survey package version 3.0.2 were used for all analyses.

The Human Subjects Division at the University of Washington and ethical review committees for each study site approved the study protocol. Each participant provided written informed consent in English or his or her preferred language.

Results

Participant characteristics at enrollment

Of the 1013 HIV serodiscordant couples who were enrolled, 67% were couples in which the woman was living with HIV and the man was HIV-uninfected, nearly all were married, and the median duration of their partnership was 2.3 years for couples with HIV-infected women and 5.9 years for couples with HIV-infected men (Table I). Couples had a median of 2 children (interquartile range [IQR] 1-3) and 56% of couples had no children together. The median age of women and men was 27 years (IQR 22-32) and 32 years (IQR 27-39), respectively. Couples had a median of 5 sex acts (IQR 3-10) per month and 64% reported at least one condomless sex act within the past month. Half of women were using no contraception and 80% of couples indicated a desire for more children in the future, including 9% who reported currently trying to conceive.

Table I. Characteristics of HIV serodiscordant couples at enrollment into the Partners Demonstration Project.

| Couples where the woman was HIV-infected (N=679) | Couples where the man was HIV-infected (n=334) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-infected women n=679 | HIV-uninfected men N=679 | HIV-uninfected women n=334 | HIV-infected men n=334 | |

| Median (IQR) or N (%) | ||||

| Couple characteristics | ||||

| Partnership duration (years) | 2.3 (0.9-6.0) | 5.9 (1.9-11.6) | ||

| Married to study partner | 636 (93.7) | 322 (96.4) | ||

| Have no children together | 443 (65.2) | 128 (38.3) | ||

| Individual demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 26 (22-30) | 30 (26-37) | 29 (24-35) | 35 (30-42) |

| Number of children | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-3) | 2 (1-3) | 3 (1-5) |

| Number of sex acts with study partner (past month) | 6 (3-12) | 6 (3-12) | 5 (3-8) | 4 (2-8) |

| Condomless sex with study partner (past month) | 453 (66.7) | 458 (67.5) | 198 (59.3) | 190 (56.9) |

| Additional partners (past month) | 7 (1.0) | 79 (11.6) | 5 (1.5) | 32 (9.6) |

| Contraceptive use | ||||

| Highly effective method (injectable, oral, implant, IUD, tubal ligation/hysterectomy) | 159 (23.4) | 115 (34.4) | ||

| Condoms | 65 (9.6) | -- | 30 (9.0) | |

| Other/Post-menopausal | 2 (0.3) | -- | 6 (1.8) | |

| Using no contraception | 318 (46.8) | -- | 185 (55.4) | -- |

| Currently pregnant* | 141 (20.8) | -- | -- | -- |

| Fertility desire | ||||

| Wants no more children | 130 (19.2) | 120 (17.7) | 125 (37.5) | 116 (34.7) |

| Currently pregnant (self of partner) | 141 (20.1) | 141 (20.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Currently trying to get pregnant | 47 (6.9) | 40 (5.9) | 23 (6.9) | 22 (6.6) |

| Within the next three years | 201 (29.6) | 230 (33.9) | 108 (32.4) | 115 (34.4) |

| More than three years from now | 47 (6.9) | 35 (5.2) | 14 (4.2) | 17 (5.1) |

| Don't know | 113 (16.6) | 113 (16.6) | 63 (18.9) | 64 (19.2) |

| Individual medical characteristics | ||||

| Treated for genital tract infection | 69 (10.2) | 8 (1.2) | 18 (5.4) | 8 (2.4) |

| Circumcised (men only) | -- | 454 (67.0) | -- | 148 (44.3) |

| CD4 count cells/mm3 | 451.5 (285-660) | -- | -- | 404.0 (225-595) |

| Viral load (log10 copies/ml) | 4.38 (3.65-4.88) | -- | -- | 4.82 (4.33-5.26) |

HIV-uninfected women were not eligible to enroll if pregnant.

Fertility intentions

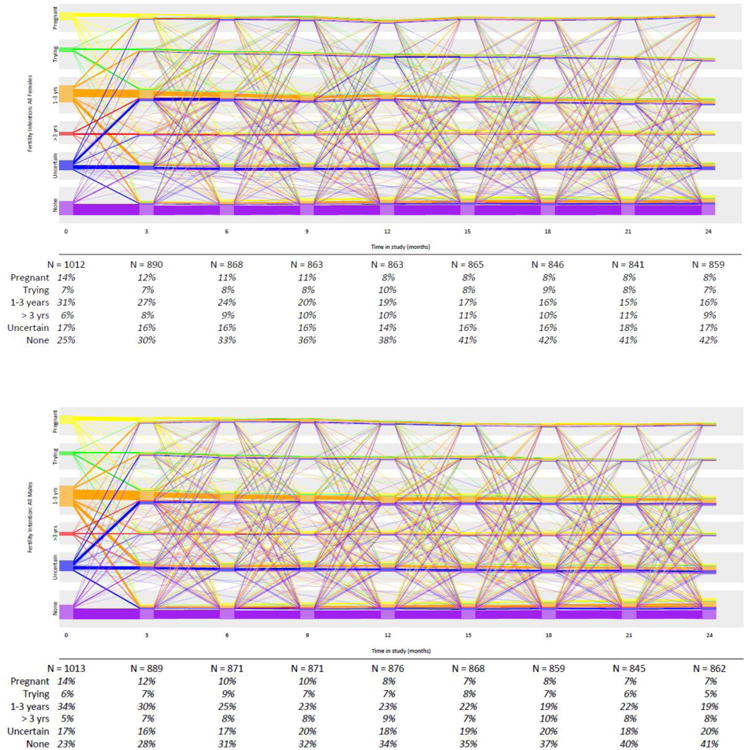

Self-reported fertility intentions fluctuated often during the two year follow up period for women and men, with the exception of those who declared a desire for no more children at enrollment who tended to maintain that response (Figure Ia). For example, 70 women (7%) indicated that they were “currently trying” to become pregnant at enrollment. Three months later, 52.9% of these women reported still trying, while 28.6% desired a child in ≥1 year, 5.7% no longer desired a future child, 7.1% had become pregnant, and 5.7% reported their desire as “unknown”. There were similar patterns of fluctuation among women who initially indicated desiring a child in ≥1 year or being uncertain about their desire. The pattern of pregnancy desires was similar among men (Figure Ib) and when disaggregated by HIV status (data not shown).

Figure I. Fertility intentions reported by a) women and b) men during quarterly follow up visits for the Partners Demonstration Project.

Each line represents data from one person and line color represents the fertility intention at baseline and is carried throughout follow up time. Lines move up or down to reflect changes in fertility intentions from one quarterly visit to the next. The individual lines have been arranged to depict consistency in fertility intention so that people with the same intention throughout the study are represented in straight lines. When multiple people maintain the same fertility intention throughout the entire study, the graphic depicts individuals' lines as a thicker block of lines. Percentages in the lower table show the aggregate number of people with the designated fertility intention at each quarterly time period and do not reflect past fertility intention.

Pregnancy incidence

During follow up, 156 women living with HIV and 88 HIV-uninfected women had at least one incident pregnancy, including 28 women living with HIV and 7 HIV-uninfected women who had two pregnancies each. The overall pregnancy incidence was 18.5 per 100 person years among HIV-uninfected women (95% confidence interval [CI] 15.0-22.7) and 18.7 per 100 person years among women living with HIV (95% CI 16.0-21.6, Table II).

Table II. Association of fertility intention with pregnancy.

| Pregnancy incidence rate* (Pregnancies/person time in follow up) | % quarterly intervals with pregnancy | OR (95% CI) p-value | Adjusted** OR (95% CI) p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women living with HIV | ||||

| With immediate fertility intention | 76.6 (51/66.6) | 12.4% (51/411) | 5.08 (3.58, 7.21) p<0.0001 | 3.43 (2.38, 4.93) p<0.0001 |

| Without immediate fertility intention | 14.5 (133/918.9) | 2.7% (133/4900) | ||

| HIV-uninfected women | ||||

| With immediate fertility intention | 55.7 (20/35.9) | 9.0% (20/221) | 3.43 (2.11, 5.60) p<0.0001 | 2.06 (1.22, 3.49) p=0.007 |

| Without immediate fertility intention | 15.7 (75/476.8) | 2.8% (75/2663) | ||

per 100 person years.

Adjusted for age, number of children, partnership duration, use of effective contraception.

Among women living with HIV, reporting an immediate fertility desire was strongly associated with becoming pregnant within the subsequent 6 months (occurring 12.4% of the time when immediate desire was reported and 2.5% of the time when no immediate desire was reported); this finding was similar for HIV-uninfected women. Women living with HIV were 3 times as likely (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.43, 95% CI 2.38-4.93) and HIV-uninfected women were twice as likely (adjusted OR 2.06, 95% CI 1.22-3.49) to be pregnant at the quarterly visit subsequent to reporting an immediate fertility intention relative to women without immediate intention (including intention in 1-3 years, ≥3 years, never or unknown). Of the 279 incident pregnancies, 25.4% were preceded by a report of immediate fertility intention during the preceding 6 months. Retrospectively, however, women reported that 70.8% of their pregnancies were intended.

Use of PrEP and ART during the peri-conception period

Uptake and adherence to the integrated PrEP and ART strategy was very high in the cohort overall, reflected in the estimated 96% reduction in HIV incidence.(6) When participants were using ART, 90% had viral load <400 copies/ml, consistent with high adherence. In the 6 months preceding pregnancy, 82.9% of couples used either PrEP or ART, 14.5% used some ART and/or PrEP but with inconsistent use, and 2.6% used neither PrEP nor ART (Table III). Of 189 couples consistently using either PrEP or ART prior to pregnancy, 31.7% concurrently used PrEP and ART, 21.7% used PrEP only, and 46.6% used ART only. Among the 81 couples who were using ART only (61 couples with HIV-infected women and 20 with HIV-infected men), 91.2% of the HIV-uninfected partners had discontinued PrEP due to sustained (i.e., >6 months) ART use by their partner living with HIV, consistent with the protocol-defined strategy for PrEP use to be integrated with ART use. ART or PrEP was used during 98% of periods when couples had an immediate pregnancy intent, which tended to be a greater frequency than periods with other pregnancy intentions (chi-square p<0.0001).

Table III. Use of PrEP and ART during 6 months preceding pregnancy.

| Couples with HIV-infected women N=161 | Couples with HIV-uninfected women N=67 | All couples N=228 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PrEP or ART used consistently within couples, N (%) | 131 (81.4) | 58 (86.6) | 189 (82.9) |

| ---PrEP and ART consistently used within couple, N (%) | 40 (24.8) | 20 (29.4) | 60 (26.3) |

| ---PrEP only used within couple | 30 (18.6) | 11 (16.4) | 41 (18.0) |

| ---ART only used within couple | 61 (37.8) | 27 (40.2) | 88 (38.6) |

| PrEP and/or ART prescribed but not consistently, N (%) | 25 (15.5) | 8 (11.9) | 33 (14.5) |

| Neither PrEP nor ART used within couple, N (%) | 5 (3.1) | 1 (1.5) | 6 (2.6) |

Restricted to pregnancies that occurred at least 6 months after study enrollment.

Among couples who became pregnant during the study, (36/262) 13.7% reported having ever used medically assisted reproduction (including sperm washing and intrauterine insemination) and (57/262) 21.8% reported using self-insemination at any point prior to the pregnancy being identified. Data on whether these techniques were associated with incident pregnancies during the study were not collected.

HIV incidence

There were a total of 4 incident HIV seroconversions during the study (3 women and 1 man), none of which occurred during the 6 months preceding pregnancy. One woman seroconverted for HIV after becoming pregnant unintentionally. She had no detectable tenofovir at her seroconversion visit and had previously reported ending her relationship with her study partner prior to her pregnancy and beginning a relationship with a new partner whose HIV status was unknown to her.

Discussion

In this open-label delivery study of a scalable model of integrated PrEP and ART implementation for high risk HIV serodiscordant couples, we saw high pregnancy incidence of 18% per person per year and frequent use of an integrated PrEP and ART strategy prior to pregnancy. There were no HIV transmissions in the six months preceding pregnancy. PrEP and ART were feasible safer conception strategies used by most of the couples who became pregnant.

Attempting pregnancy is a reproductive right and the ability to choose between effective HIV risk reduction strategies when family building is desired is an important accompanying right, including access to adoption and sperm and gamete donation. Early in the HIV epidemic, fertility experts began leveraging the technology of sperm washing coupled with intrauterine insemination in order to facilitate pregnancy without sexual HIV transmission within HIV serodiscordant couples (10). This technique was first adopted as a safer conception strategy in the early era of HIV treatment when antiretrovirals were not yet optimized and the HIV prevention benefit of ART to suppress HIV viremia was unknown. Now that antiretrovirals are widely recognized as powerful and recommended HIV prevention strategies, they provide a more accessible and affordable option to HIV-affected couples with normal fertility that desire pregnancy. In addition, since conception with medically assisted techniques (including sperm washing) requires careful observation of the menstrual cycle and pre-conception fertility workups, these options may actually prolong the time to conception for couples with normal fertility and their availability is limited in lower resource settings (11,12). Nonetheless, a substantial proportion of couples reported experience with these techniques and/or self-insemination and they remain important services to promote with realistic expectations of success rates and costs, when they align with couple preferences (13).

When conducted under a framework of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care, HIV prevention counseling offers opportunities for provider-initiated discussions about fertility intentions, contraception, and planning for pregnancy. In our study among HIV serodiscordant couples who had been together for several years on average and who met with HIV prevention counselors and care providers every 3 months, more than half of the pregnancies occurred without any prior declared pregnancy intention or sooner than preferred. Worldwide, 40% of pregnancies are estimated to be unintended and while the resulting children are often wanted, more pregnancy preparation can yield better pregnancy outcomes (14). Guidance for providers to integrate discussions about fertility desires into HIV prevention counseling and balance this important area with other priority health topics is urgently needed to foster explicit discussions within couples and to increase the use of PrEP and ART during the peri-conception period. In our study, only a quarter of pregnancies were preceded by a declared immediate fertility intention, highlighting a role for providers to initiate discussion repeatedly and set a positive tone about safer conception, even when pregnancy intent is not immediate. In addition, a paradigm shift that encourages people to consider their pregnancy desires and plan pregnancies can improve the uptake of sexual and reproductive health care, including the uptake of including safer conception, when warranted.

The provision and promotion of safer conception services for HIV serodiscordant couples is an opportunity to test and evaluate delivery strategies in a population with known, and socially expected, pregnancy desires. As couples-based safer conception programs are implemented, it is important to adapt and extend them to HIV-affected individuals with fertility desires who may not seek couples-based services. Providing opportunities for HIV-affected young women and men to plan pregnancies and discuss options with a provider will strengthen their ability to discuss HIV prevention with partners, disclose HIV status to partners, and incorporate HIV risk reduction strategies, as demonstrated in multiple clinics in South Africa and Uganda (15-17). In addition, integration of HIV and reproductive health services offers opportunities to expand contraceptive services, by offering highly effective reversible contraception and meeting the needs of couples and individuals who express desire to prevent pregnancy.

The tools to support individuals and couples affected by HIV to fulfill their pregnancy desires without HIV transmission are known and multiple tools are widely accessible. Demonstration projects, such as this one, have shown great success in the implementation of safer conception services with high rates of pregnancy and no peri-conception HIV transmissions. It is time to encourage demand for safer conception services among the community and promote holistic discussion of reproductive goals among people affected by HIV. Widespread scale up of sexual and reproductive health services that are integrated with HIV prevention is imperative to ensure that individual and couple goals for family building are safely met.

Acknowledgments

We thank the couples who participated in this study for their motivation and dedication and the referral partners, community advisory groups, institutions, and communities that supported this work.

Funding: This work was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R00HD076679). The Partners Demonstration Project was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1056051), the National Institute of Mental Health of the US National Institutes of Health (R01 MH095507) and the United States Agency for International Development (AID-OAA-A-12-00023). This work is made possible by the generous support of the American people through USAID; the contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, NIH, or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Partners Demonstration Project Team: Coordinating Center (University of Washington) and collaborating investigators (Harvard Medical School, Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital): Jared Baeten (protocol chair), Connie Celum (protocol co-chair), Renee Heffron (project director), Deborah Donnell (statistician), Ruanne Barnabas, Jessica Haberer, Harald Haugen, Craig Hendrix, Lara Kidoguchi, Mark Marzinke, Susan Morrison, Jennifer Morton, Norma Ware, Monique Wyatt

Project sites: Kabwohe, Uganda (Kabwohe Clinical Research Centre): Stephen Asiimwe, Edna Tindimwebwa

Kampala, Uganda (Makerere University): Elly Katabira, Nulu Bulya

Kisumu, Kenya (Kenya Medical Research Institute): Elizabeth Bukusi, Josephine Odoyo

Thika, Kenya (Kenya Medical Research Institute, University of Washington): Nelly Rwamba Mugo, Kenneth Ngure

Data Management was provided by DF/Net Research, Inc. (Seattle, WA). PrEP medication was donated by Gilead Sciences.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals: All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Washington institutional review board, national research ethics committees for each study site, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Ngure K, Baeten JM, Mugo N, et al. My intention was a child but I was very afraid: fertility intentions and HIV risk perceptions among HIV-serodiscordant couples experiencing pregnancy in Kenya. AIDS care. 2014;26(10):1283–1287. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.911808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pintye J, Ngure K, Curran K, et al. Fertility Decision-Making Among Kenyan HIV-Serodiscordant Couples Who Recently Conceived: Implications for Safer Conception Planning. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2015 Sep;29(9):510–516. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthews L, Mukherjee J. Strategies for harm reduction among HIV-affected couples who want to conceive. AIDS and behavior. 2009;13(Supplement 1):S5–S11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heffron R, Davies N, Cooke I, et al. A discussion of key values to inform the design and delivery of services for HIV-affected women and couples attempting pregnancy in resource-constrained settings. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18(6 Suppl 5):20272. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.6.20272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Guideline on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baeten JM, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, et al. Integrated delivery of antiretroviral treatment and pre-exposure prophylaxis to HIV-1-serodiscordant couples: A prospective implementation study in Kenya and Uganda. PLoS medicine. 2016 Aug;13(8):e1002099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahle EM, Hughes JP, Lingappa JR, et al. An empiric risk scoring tool for identifying high-risk heterosexual HIV-1-serodiscordant couples for targeted HIV-1 prevention. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2013 Mar 1;62(3):339–347. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e622d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morton JF, Celum C, Njoroge J, et al. Counseling Framework for HIV-Serodiscordant Couples on the Integrated Use of Antiretroviral Therapy and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2017 Jan 01;74(1):S15–s22. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Aug 11;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semprini AE, Levi-Setti P, Bozzo M, et al. Insemination of HIV-negative women with processed semen of HIV-positive partners. Lancet. 1992 Nov 28;340(8831):1317–1319. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semprini AE, Macaluso M, Hollander L, et al. Safe conception for HIV-discordant couples: insemination with processed semen from the HIV-infected partner. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 May;208(5):402.e401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Carli G, Palummieri A, Liuzzi G, Puro V. Safe conception for human immunodeficiency virus-discordant couples: the preexposure prophylaxis for conception alternative. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 Jan;210(1):90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngure K, Kimemia G, Dew K, et al. Delivering safer conception services to HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya: perspectives from healthcare providers and HIV serodiscordant couples. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2017 Mar 08;20(Suppl 1):52–58. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.2.21309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korenbrot CC, Steinberg A, Bender C, Newberry S. Preconception care: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2002 Jun;6(2):75–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1015460106832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies N. AIDS 2016. Durban, South Africa: 2016. Uptake and clinical outcomes from a primary healthcare based safer conception service in Johannesburg, South Africa: findings at 7 months Abstract #THPDC0105. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaida A. AIDS 2016. Durban, South Africa: 2016. High planned partner pregnancy incidence among HIV-positive men in rural Uganda: implications for comprehensive safer conception services for men Abstract #THPDC0106. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yende N. AIDS 2016. Durban, South Africa: 2016. Clinical outcomes and lessons learned from a safer conception clinic for HIV-affected couples trying to conceive Abstract #THPDC0104. [Google Scholar]