Abstract

Background

The transitional period from late adolescence to early adulthood is a vulnerable period for weight gain, with a twofold increase in overweight/obesity during this life transition. In the United States, approximately one-third of young adults have obesity and are at a high risk for weight gain.

Purpose

To describe the design and rationale of a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) sponsored randomized, controlled clinical trial, the Healthy Body Healthy U (HBHU) study, which compares the differential efficacy of three interventions on weight loss among young adults aged 18–35 years.

Methods

The intervention is delivered via Facebook and SMS Text Messaging (text messaging) and includes: 1) targeted content (Targeted); 2) tailored or personalized feedback (Tailored); or 3) contact control (Control). Recruitment is on-going at two campus sites, with the intervention delivery conducted by the parent site. A total of 450 students will be randomly-assigned to receive one of three programs for 18 months. We hypothesize that: a) the Tailored group will lose significantly more weight at the 6, 12, 18 month follow-ups compared with the Targeted group; and that b) both the Tailored and Targeted groups will have greater weight loss at the 6, 12, 18 month follow-ups than the Control group. We also hypothesize that participants who achieve a 5% weight loss at 6 and 18 months will have greater improvements in their cardiometabolic risk factors than those who do not achieve this target. We will examine intervention costs to inform implementation and sustainability other universities. Expected study completion date is 2019.

Conclusions

This project has significant public health impact, as the successful translation could reach as many as 20 million university students each year, and change the current standard of practice for promoting weight management within university campus communities. ClinicalTrial.gov: NCT02342912

Keywords: social media, weight loss, college, university, young adults, SMS

1. Introduction

Young adulthood is a public health risk period for weight gain. The greatest incidence of major weight gain (defined by >=5kg or more) occurs among those aged 25–34 years (1). When examining national data, there is an increasing trend in obesity prevalence by age with 17% of children and adolescents (ages 2–19) having obesity, compared with 32.3% of young adults (ages 20–39) and 40.2% of adults (ages 40–59) (2). When including overweight, the trend indicates an almost doubling of obesity risk: the prevalence of overweight/obesity among 12–19 year olds averages about 33.6% (3), while prevalence among 20–39 year olds averages 63.5% for men and 59.5% for women(4). The health effects of obesity are well documented and range from increased risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes(5) to depression and stigmatization(6). Metabolic risks are largely unstudied among young adults; however, undiagnosed cardiometabolic dysfunction is of primary concern (7). Among college students, 26–40% had at least one abnormal component of the Metabolic Syndrome(7, 8). Young adulthood appears to be a potent time-frame for early intervention to address overweight and other risk factors for chronic disease (1, 7).

Digital strategies, such as social media, are broadly used and accepted as forms of communication among college students (9–12). There are over 1.7 billion active Facebook users worldwide, which is more than Gmail, Yahoo, and Hotmail combined (13, 14). According to 2015 data, approximately 80% of young adults were Facebook users (15). Text messaging among young adults was also high: 100% of those ages 18–29 years and 98% those ages 30–49 years reported using their phone to text (16). Among those aged 18–49 years, text messaging was used more frequently than email, voice calling and video calling (16). This high use indicates that social media might be a good channel for reaching young adults. Indeed, digital strategies have been shown to deliver effective weight loss programs and have included channels such as the Internet (17–19), Twitter (20, 21), self-weighing with electronic feedback (22), and personal digital assistants (PDA’s) (23–25). However, none of these studies were designed specifically for young adults. Pilot work by the investigative team demonstrated short term efficacy of a personalized weight loss program delivered to college students via Facebook and text messaging, with weight losses of 2.4kg at 8 weeks (26). This pilot study was designed to use popular digital channels for delivering weight loss information to extend the reach of programming to young adults.

University campus communities offer a range of health and mental health services. Approximately 20 million students are enrolled in an undergraduate or post-baccalaureate program (27, 28). Yet, obesity treatment and prevention efforts have lagged behind other health-related programming on campuses (29). For example, of the 10 universities with the largest student enrollment, only 3 offered weight loss programming specific for undergraduates, on campus at no additional cost, and delivered by university-funded treatment providers. In comparison, all of these schools offered no-cost and continual enrollment programming for the other high-risk health needs, including alcohol and other drug services and eating disorders (29). University settings could provide sustainable locations for the identification of health risks, such as overweight and obesity, and provide additional offerings for health related programming, such as evidence-based weight loss programs.

2. Overview/Primary research goals

The aim of this randomized controlled trial is to examine the efficacy of two 18-month weight loss treatments compared with an 18-month contact control group, with intervention content delivered via Facebook and text messaging. In this trial, 450 students (ages 18–35) with overweight/obesity will be recruited from two sites: The George Washington University (GWU) and University of Massachusetts-Boston (UMB). Ages 18–35 was selected as a target range for young adults, which consistent with other US-based (e.g., (30, 31) and International trials(32). Social media as an intervention tool was chosen in that it is technology that the students are already accustomed to and it does not require face-to-face intervention sessions. Assessments are conducted at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months post baseline, with the primary outcome being weight loss at 18 months. The secondary aim is to evaluate changes in metabolic risk factors among those participants who have maintained at least 5% weight loss at 18 months. Finally, additional formative work is being conducted to evaluate the implementation feasibility of this intervention on university campuses, including an assessment of costs as well as the sustainability infrastructure using the PRISM (Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model) (33) model as a guide.

3. Study Design/Methods

3.1. Settings

The recruitment sites for this study are The George Washington University and the University of Massachusetts-Boston, with Institutional Review Board approval being obtained from both sites. While those two universities were the primary target, students within the greater Washington DC and Boston areas were eligible to take part in the study.

3.2. Participants and enrollment

Participants are enrolled in cohorts, beginning in May 2015, and continuing through December 2017. A total of 450 students (225 at each site) are randomized into one of three treatment arms. Enrollment occurs across multiple cohorts throughout the year. Several methods are used to recruit and enroll participants in the study, including mass emails, listserv emails, classroom talks, flyers, tabling events, health and wellness fair presentations, shuttle bus posters, Facebook advertisements, and local and college newspapers. Mass emails and listserv emails are proving to be the most effective methods of recruitment. The study was titled, Healthy Body Healthy U, or HBHU for short, and the recruitment materials place an emphasis on it being a research study to interested individuals. The recruitment materials also place an emphasis on helping to promote a healthier lifestyle via social media so that it is convenient for participants.

Individuals are eligible if they are aged 18–35 years, have a BMI of 25–45 kg/m2, attend a college/university in the Greater DC/Boston area, are active Facebook users (logged in within the last month), fluent in English, and had regular text message access. Participants are excluded if they reported currently trying to gain weight, using steroids, a history of weight loss surgery, or are participating in another weight loss or physical activity study. Additional exclusion criteria are based upon participant safety for a weight loss program, or causing unintentional weight change making study effects difficult to determine. Health-care provider clearance is required prior to participation for those individuals who endorsed “yes” for any Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) (34) questions, and any reported diagnosis of untreated hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, or heart disease. Specific inclusion/exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria |

|---|

|

|

|

| Exclusion Criteria |

|

Participants who receive health-care provider consent may be eligible to participate in study

Potential participants complete an online screening questionnaire, which is then reviewed by trained study team members. Study team members contact individuals by phone for further screening, and those who meet criteria are scheduled for an in-person screening visit (Pre-Enrollment Visit). At the Pre-Enrollment session, the following steps are taken: 1) verify eligibility criteria, including height, weight, and blood pressure measurements, 2) explain the study in more detail prior to obtaining written consent, 3) provide participants with an ActiGraph accelerometer, access to the online ASA-24 food recall system and to the online survey to complete psychosocial measures, and 4) schedule the participant for his/her second baseline visit (First Checkpoint Visit). Pre-Enrollment sessions last approximately 40–50 minutes.

Participants return for their First Checkpoint Visit no less than 7 days after their Pre-Enrollment visit, allowing sufficient time for participants to complete the ActiGraph wear-time, online dietary recalls, and psychosocial surveys. At this visit, body weight and abdominal circumference are measured by trained research assistants, and a fasting blood sample is obtained for the determination of glucose, insulin, lipid profile including triglyceride concentrations. See Table 2 for an overview of all measures and their administration time points, which are discussed in more detail in Section 4. Once all measures have been completed and verified by study staff, participants are randomized into one of three treatment groups using a computer-based algorithm through the REDCap software system: 1) targeted content (Targeted); 2) tailored or personalized feedback (Tailored); or 3) contact control (Control), identified to participants as, Green, Purple and Blue, respectively.

Table 2.

Data collection schedule by Time Point in the Study

| Data Collected | Collection Time Point

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 Months | 12 Months | 18 Months | |

| Anthropomorphic | ||||

| Weight (Primary Outcome) | X | X | X | X |

| Height | X | X | X | X |

| Abdominal Circumference | X | X | X | X |

| Body Mass Index | X | X | X | X |

| Medical | ||||

| Blood Pressure | X | X | X | X |

| Fasting Blood Sample | X | X | X | |

| Medication Use | X | |||

| Medical Events (via monthly check-in texts) | X | X | X | X |

| Health Expense Form | X | X | X | |

| Behavioral and Cognitive | ||||

| PAR-Q – PA | X | |||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) | X | |||

| Physical Activity (ActiGraph) | X | X | X | X |

| Diet (ASA-24 On-Line Log) | X | X | X | X |

| Sleep | X | X | X | X |

| Physical Activity (IPAQ) | X | X | X | X |

| Physical Activity Self-Efficacy | X | X | X | X |

| Weight Management Social Support Survey (WMSI) | X | X | X | X |

| Interpersonal Support (informational, emotional, communication) | X | X | X | |

| Cigarettes, E-Cigarettes (use, perceptions, weight control) | X | X | X | X |

| Social Media Engagement | X | X | X | X |

| Social Networking | X | X | X | X |

| Social Norms | X | X | X | X |

| Weight Self-Efficacy | X | X | X | X |

| Psychological Assessment | ||||

| Bipolar & Schizophrenia (Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Based Bipolar Disorder Screening Scale) | X | |||

| Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS) | X | X | ||

| Perceived Stress | X | X | X | X |

| Stress Management | X | X | X | X |

| Body Image Quality of Life | X | X | X | X |

| Other Questionnaires | ||||

| Demographics | X | |||

| Contact Information | X | X | ||

Randomization is stratified by BMI (<30 or ≥30 kg/m2) to ensure balance between each of the three treatment groups. Following randomization, participants are sent a “friend” request for an invitation to join their respective “secret” Facebook groups (i.e., a private group that only researchers can invite members to join) and given appropriate informational print materials corresponding to their group assignments to ensure they understand their group and are able to connect to the online intervention materials. Handouts also cover important exercise safety and calorie, weight, and physical activity goals. The randomization occurs at the First Checkpoint visit which lasts approximately 40–50 minutes. Intervention begins for all three groups in one cohort at the same time, within 8 weeks of participant’s First Checkpoint visit. Follow-up visits occur at three time-points (6, 12, and 18 months after randomization). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Intervention and Assessment Schedule

| Time Point | Event |

|---|---|

| 0 | Recruitment and Screening |

| Days Later | Pre-Enrollment |

| 1 Week Later | First Checkpoint (Randomization) |

| Months 1–6 | Weekly Content Delivery |

| Month 6 | Month 6 Checkpoint Visit |

| Months 7–9 | Bi-Weekly Content Delivery |

| Months 10–12 | Monthly Content Delivery |

| Month 12 | Month 12 Checkpoint |

| Months 13–18 | Bi-Monthly Content |

| Month 18 | Final Checkpoint |

Italics = assessments

Non-italicized = program content delivery

3.3 Intervention

3.3.1. Targeting and Tailoring Health Interventions

Health communication delivery of messaging can occur in a variety of forms. Targeted messages are those that are applicable to a broad audience who are similar in some way (35), for example college students or women. Tailored communication strategies are personalized on pre-determined variables (36) and tend to be more efficacious compared with targeted interventions (37). A meta-analysis of 57 studies also reported that tailored interventions for health behavior change outperform generic or targeted interventions (38). However, this level of personalization requires both staff and participant burden in order to appropriately tailor messages to one’s individual psychosocial and behavioral characteristics. It is hypothesized that the tailored intervention would be more efficacious; however, we acknowledge that a tailored intervention with extra text message inquiries and responses could lead to a burden that makes the intervention less desirable despite the known advantages to tailoring an intervention Additionally, of importance are both the cost and potential reach and sustainability of a program on university campuses, both of which are important factors in future program implementation.

3.3.2. Theoretical Framework

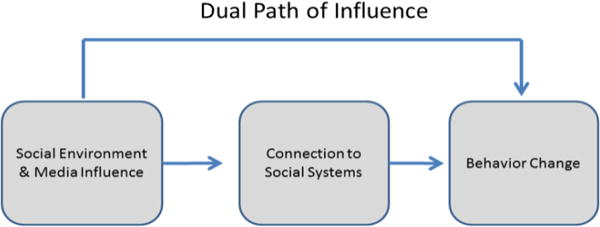

This program is informed by an integrated theoretical framework incorporating Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)(39) and behavior change principles(40–42). The Model of Triadic Reciprocal Causation(43, 44), emphasizes the importance of environmental, cognitive/personal, and behavioral skills in behavior change. Behavioral skills addressed (i.e., self-monitoring, planning, and goal setting) are often termed self-regulatory processes and are important components of behavior change as they influence self-efficacy (45). Bandura proposed a model to describe how technology can enhance the impact of health promotion programs via the use of tailoring and individualized feedback (46). While the social environment and media (in our case college campus and Facebook), can directly promote behavior change, enhancing social support input and connections to social systems via texting and posts on Facebook, also has a pathway to promote behavior change (i.e., weight loss). This Dual Path of Influence Model (46) (see Figure 1) posits that it is both the support and guidance provided by the social system, and the level of connection to that system that is important for behavior change. This study is utilizing and testing this framework.

Figure 1.

3.3.3. Intervention Content & Delivery

Delivery of intervention content has been controlled for mode and type, such that all participants receive information through the same three channels: Facebook, text messaging, and summary reports. Thus, while the mode of delivery is controlled for, the content that is delivered varies by group assignment. All content was pre-programmed so that delivery via Facebook and SMS Text Messages could be automated and standardized for all cohorts.

Targeted Group

The Targeted group receives materials that are based on content delivered in an 8-week intervention for weight loss among young adults (26). For that pilot study (26), evidence-based weight loss protocols (47, 48) were adapted to include a focus on students and young adults and to be delivered via the Facebook channel.

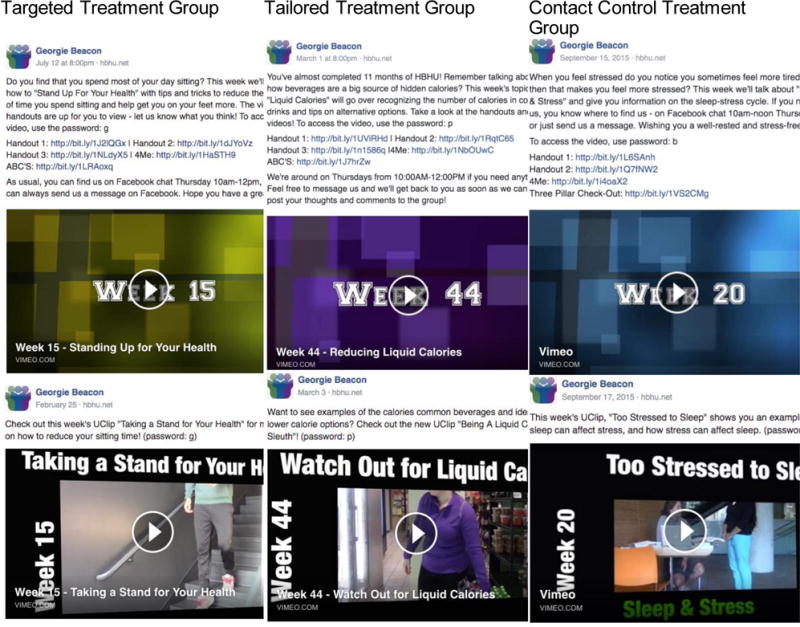

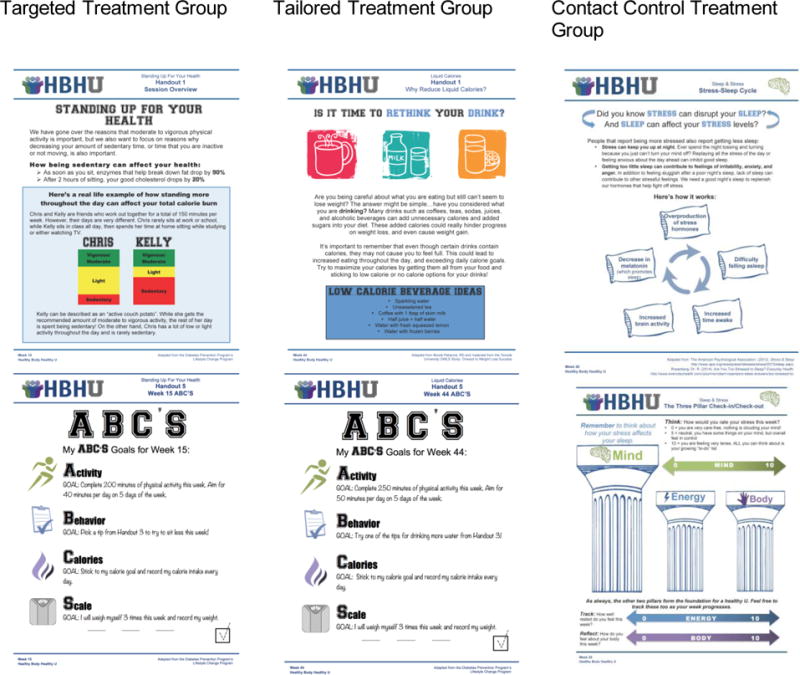

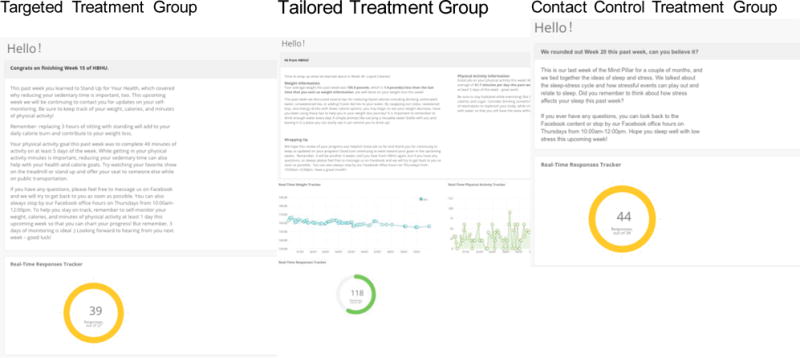

For this larger trial, the Diabetes Prevention Program (49, 50) content was used as an overall framework for program content, and the pilot materials that were targeted to university students served as a guide for adapting the DPP to the student population. Each week, participants receive access to handouts and two videos, one video is a didactic lesson of the week from their peer HBHU student coach, and the other video is of peers modeling a behavioral tip that was covered in the handouts and in the video for the week (UClip; see Figure 2. The same peer HBHU student coach appeared in all of the standardized pre-recorded didactic videos for each treatment arm and across both study sites. The handouts, adapted from the DPP program, were designed to be appealing to university students in terms of content and look and feel (see Figure 3). Similarly, the videos were also created to be relevant to typical university student situations, such as juggling school, homework, friends, and family; making good choices in the cafeteria; and living with roommates. Input on content was obtained from undergraduate and graduate student members of the study team. See Table 4 for weekly intervention topics.

Figure 2.

Sample screen-shots of didactic and peer-lead videos for participants

Figure 3.

Participant Handouts by Treatment Group

Table 4.

Intervention Topics by Week in the Program and Group Assignment

| Intervention Topic | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Week in Program | Targeted/Tailored Treatment Group | Contact Control Treatment Group |

| Week 1 | Welcome to the Program | Welcome to the Program |

| Week 2 | Self Monitoring and Effective Goal Setting | Pillar 1: Mind |

| Week 3 | Physical Activity: Getting Started | Pillar 2: Energy |

| Week 4 | Making Over Your Meals | Pillar 3: Body |

| Week 5 | Ways to Eat Healthy | The Science of Stress |

| Week 6 | Tip the Calorie Balance | Sources of Stress |

| Week 7 | Being Active – A Way of Life | Signs of Stress |

| Week 8 | Take Charge of What’s Around You | Time Management |

| Week 9 | Talk Back to Negative Thoughts | How Much Sleep is Enough |

| Week 10 | Making Social Cues Work For You | Sleep Overview |

| Week 11 | Jumpstart Your Activity Plan | What Disrupts Sleep |

| Week 12 | Choosing Healthy Options When Eating Out | Naps: Good or Bad |

| Week 13 | Planning and Taking Charge When Eating Out | Body Attitude Best Practices |

| Week 14 | Problem Solving | Power of Body Attitude |

| Week 15 | Standing Up For Your Health | Body Attitude in the Media |

| Week 16 | The Slippery Slope of Lifestyle Change | Building Body Attitude |

| Week 17 | Managing Stress | Stress & the Immune System |

| Week 18 | Ways to Stay Motivated | Mindfulness |

| Week 19 | More Volume, Fewer Calories | Procrastination |

| Week 20 | Strengthen Your Exercise Program | Sleep & Stress |

| Week 21 | Time Management and Sleep | Sleep & Energy Balance |

| Week 22 | Time and Sleep Strategies | Hydration & Dehydration |

| Week 23 | Mindful Eating | Caffeine & Energy Drinks |

| Week 24 | Body Attitude | Technology & Your Sleep |

| Week 25 | Handling Holidays, Vacations, and Special Occasions | Protect the Skin You’re In |

| Week 26 | Taking It One Meal At A Time | Ideal vs. Real |

| Week 28 | Assertiveness | Mindfulness 2 |

| Week 30 | Lifestyle Activity | 7 Sectors of Wellness |

| Week 32 | Eating Favorite Foods | Waking Up Energized |

| Week 34 | What if the Scale Doesn’t Budge | Energy Fluctuations |

| Week 36 | Social Support | Society and Body Attitude |

| Week 40 | Smart Snacking | Context & Body Attitude |

| Week 44 | Liquid Calories | Mind focused Mindfulness |

| Week 48 | Stress And Your Weight | Mindfulness (Energy) |

| Week 52 | Reasonable Weight Goals | Mindfulness *Body) |

| Week 60 | Relapse Prevention | Wrap Up of the Mind Pillar |

| Week 68 | Long Term Weight Management Strategies | Wrap Up of the Energy Pillar |

| Week 76 | Congratulations! | Wrap Up of the Body Pillar |

The participants receive a friend request from a generic name and invitation to join a “secret” Facebook group. This group serves as the portal to access the intervention content and a platform for social support and connectivity. See Figures 2 and 3 for sample videos and handouts. To ensure confidentiality, this Facebook group is private and has a generic name. Participants are instructed on the highest level of security for their Facebook profiles to ensure the friend list remains private, if so desired. Participants recruited from each site are in groups separated by their random assignment. These postings include polls, posts, and announcements standardized across each campus. In addition to polls to encourage engagement within the social network, announcements (e.g., local farmer’s markets, stress management events) are posted to encourage engagement outside the social media environment. See Table 5.

Table 5.

Intervention Active Ingredients for first 6 months of the program by group and communication type

| Targeted Treatment Group | Tailored Treatment Group | Contact Control Treatment Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Ingredient | Communication Type (Number of posts) | |||

| Total messages per week | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | |

| Videosa | Adapted DPP Weight Loss Content | Adapted for young adult university students (n=2) | Adapted for young adult university students (n=2) | Adapted for young adult university students (n=2) |

| Handoutsb | Adapted DPP Weight Loss Content | Adapted for young adults university students (n=2) | Adapted for young adult university students (n=2) | Adapted for young adult university students (n=2) |

| Reminders | Reminder to view content and report | Adapted for young adults university students (n=2) | Adapted for young adult university students (n=2) | Adapted for young adult university students (n=2) |

| SMS Text Messagingc | Total outgoing messages per week | n=7 | n=15 | n=7 |

| High-risk behaviors related to weight loss and PA | General tips (n=2) | Personalized tips (n=2) | General tips (n=2) | |

| Reminder to self-monitor/Prompt for calorie, weight, PA data | Reminder to monitor (n=3) Prompt for data (n=3) | |||

| Feedback on number of self-monitoring days completed | N/A | General (n=1) | N/A | |

| Importance of self-monitoring | Related to weekly content (n=1) | Related to weekly content (n=1) | Related to weekly content (n=1) | |

| General monitoring info | General (n=1) | General (n=1) | General (n=1) | |

| Inquiry if monitored | Weight/PA (n=1) | Weight/PA (n=2) | 3 Pillars (n=1) | |

| Reminder to review content | General (n=2) | General (n=2) | General (n=2) | |

| Weekly Reportd | Summative (n=1) | Personalized (n=1) | Summative (n=1) | |

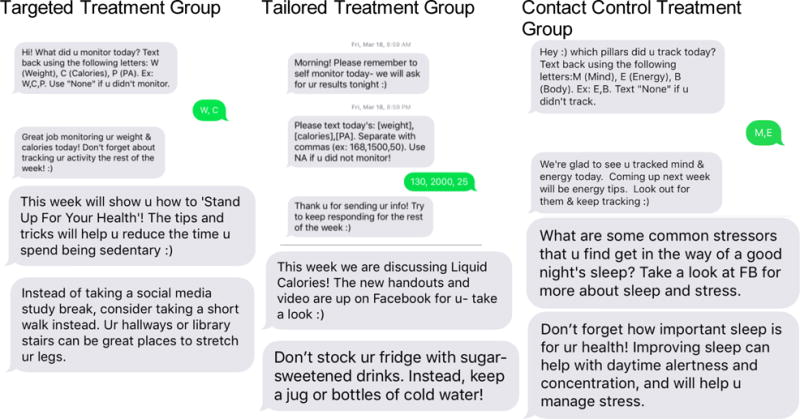

Text Messaging

Targeted participants receive generic tips and queries regarding which behavior(s) were monitored. See Table 5 and Figure 4. Targeted participants receive text messages daily (n= 7), which include both content-related tips and queries (See Table 5). Tips include topics identified as potential barriers (or high risk behaviors) related to weight loss, These high risk topics include late night snacking, meal skipping, liquid calories, lack of fruit and vegetable intake, eating/ordering out, portion control, inactivity, lack of time for exercise and/or healthy eating, stress, and being sedentary. Targeted participants receive randomly selected tips during each content week.

Figure 4.

Sample text messages by Treatment Group

Weekly Report

Each week, participants receive a summative report. A link to this report is sent via text message and participants use their Facebook login information for validation. Participants can track their overall response rate on this online report, with a tracker that gives them a percentage of texts to which they responded. Targeted group participants receive a report that summarizes the key concepts for the week (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sample screen-shots of participant weekly reports

At the First Checkpoint Visit, each participant receives intervention materials, including a tote bag with study logo and water bottle as well as digital scales (Camry, Model EB7006).

Tailored Group

All of the weight loss content delivered to the Targeted group mentioned above is also delivered to the Tailored group; their weight loss intervention content is identical in this respect. The delivery of the Facebook materials is also identical to the targeted group.

Text Messaging

Rather than receiving generic tips and queries regarding the monitored behaviors, the Tailored weight loss group receives personalized tips based on their stated barriers to weight loss chosen from the list of 10 high risk behaviors at each checkpoint, and queries for self-monitoring data. Tailored participants receive more text messages (n=15) than the targeted group in order to gather the data for the personalized feedback report and to deliver the personalized weight loss tips. These texts include both content-related tips and queries (See Table 5).

Weekly Report

As with the Targeted group, participants receive a summative report via a text message link and participants use their Facebook login information for validation. However, for the Tailored group, this report is personalized based on the information they sent via text message on their weight, physical activity, calorie monitoring. The feedback report contains personalized sections, graphs on self-reported weight change and physical activity, and a real-time tracker of text response rates (Figure 5). Tailoring was based on performance relative to the previous week and included feedback on current values for both weight and minutes of physical activity, a reminder of weekly content and goals as related to current values, and suggestions for improvement when participants were not meeting goals. Given the variability in self-monitoring, calorie feedback each week was given based on self-reported weight change translated into calories.

Tailored group participant receive the same intervention materials as Targeted participants including a tote bag with study logo and water bottle as well as digital scales (Camry, Model EB7006) to obtain calibrated weights.

In summary, differences between the Tailored and Targeted group include: personalized text message tips based on their stated barriers to weight loss, as selected from the list of high risk behaviors listed in section, text messages requesting tracking information on weight, calories, and physical activity; and a weekly personalized report that summarizes key progress based on information sent.

Healthy Body Weight Contact Control

The third intervention arm (Control) focuses on wellness topics and behaviors. To minimize differential attrition, the wellness educational topics chosen can relate to body weight such as stress, sleep, mood, and body image so that all three groups would have some information regarding a healthy body weight. These were called the three pillars of health (Body, Mind, and Energy) and were chosen based on their relation to healthy weight maintenance. The contents were delivered in an educational, rather than behavior change, format. The Control group also received no direct weight loss information nor calorie goals, this group was not a weight loss intervention. See Table 4 for weekly topics.

The delivery of the intervention content on Facebook was identical to the other two groups. Each week, participants receive access to handouts and two videos, one is a didactic video from their peer HBHU student coach that is the lesson for the week, and one that is of peers modeling a behavioral tip that was covered in the handouts and video for the week (UClip). See Figures 2 and 3.

Text Messaging

Contact control participants receive generic tips and queries regarding which behavior(s) were monitored. See Table 5 and Figure 4. The frequency of these texts matched that of the Targeted group.

Weekly Report

Just as in the other groups, each week, participants receive a link to a summative report. The link is sent via text message and participants use their Facebook login information for validation. Participants can track their overall response rate on this online report, with a tracker that gives them a percentage of texts responded to. The contact control participants receive a report that summarizes the key concepts delivered via Facebook for that week (Figure 5).

Similar to the two groups above, each participant receives intervention materials, including a tote bag with study logo and water bottle. Participants also receive a stress ball.

3.3.4. Intervention Fidelity and Engagement

Protocols were created in order to track each participant’s engagement with the program content. The three main components assessed for engagement include: 1) accessing the Facebook group, 2) response to text message, and 3) viewing weekly reports. Participants received a score of 0 (did not complete) or 1 (completed) for each of the aforementioned components. To ensure intervention fidelity, study staff contact participants who did not engage in all three components for the first three weeks of the program. As the intervention progresses, subsequent engagement blocks have less stringent total score requirements to allow participants to engage with the content as they see fit, but still ensure engagement and fidelity. Contacting participants to improve engagement also is a method employed for preventing attrition and early disengagement. Participants are also asked via text message on a monthly basis to estimate the percentage of content reviewed. Additionally, the engagement scores calculated will be utilized in future analyses when considering program dose-received, social media engagement, and participant outcomes.

4. Measures

Assessments occur at baseline (two visits), and at 6, 12, and 18 months post baseline/randomization. Participants’ anthropometric measurements of height, weight, and abdominal circumference are collected, as well as blood pressure, and psychosocial measures via survey at each assessment visit (checkpoint visit). Fasting blood samples are collected via capillary and venipuncture at baseline and months 6 and 18, for glucose, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), insulin, and lipids. Participants are reimbursed up to $25 at each checkpoint visit, with an additional $25 for those visits requiring a blood sample. See Table 2 for the schedule of measurements.

4.1. Clinic based measures

All study measurements, including clinic-based measures, are conducted by certified and trained study personnel, including a certified phlebotomist for the venipuncture blood draw. Detailed protocols and procedures were developed and deployed across recruitment sites, accompanied by training videos and online tutorials. Trained graduate and undergraduate research assistants perform data collection, with the research coordinator being present for the majority, if not all, of the data collection. If any measurement falls outside of pre-defined range, an additional measurement is recorded. The measurement classified as the outlier will be removed prior to calculation of average measurement.

4.1.1. Weight, Height, Body Mass Index (BMI)

Weight and height are measured in duplicate during each checkpoint visit, using a digital scale (Seca Model 769) and standard portable stadiometers. Participants are asked to remove bulky outer clothing and shoes prior to all measurements. Alternating between weight and height measurements, weight is recorded to the nearest 0.2 kg, while height is recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. Averages for both the height and weight measurements are calculated and recorded at each assessment time point. Body Mass Index (BMI) is calculated using the aforementioned averages (weight (kg)/height (m2)) for each checkpoint visit.

4.1.2. Blood pressure

Blood pressure measurements are taken in triplicate using a digital blood pressure monitor, OMRON HEM-907XL, with appropriately sized cuff (bladder length encircling 80–100 percent of participant’s upper arm). Participants are asked to remain seated quietly in a chair for five minutes with feet flat on the floor, back supported by the chair, with right arm unclothed and supported at heart level with right palm facing up. Three measurements are taken and recorded at two-minute intervals, from complete deflation of cuff. An average blood pressure measurement is calculated for each checkpoint visit. These protocols were adapted from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009 Health Tech/Blood Pressure Procedures Manual (51).

4.1.3. Waist Circumference

Waist circumference measurements are taken in triplicate using a cloth tape measure, rounded to the nearest 0.1 cm, and averaged. Participants are asked to remove bulky outer clothing, and to remove their shirt or expose the abdomen. The measuring tape is placed on participant’s unclothed skin at the umbilicus, ensuring the tape remained parallel with the floor and untwisted. The umbilicus was chosen as the measurement site for this trial, as it is an easily identifiable and reproducible landmark (52). A team of research assistants perform abdominal circumference measurements to ensure proper placement of the measuring tape. Each measurement is recorded upon exhale, to ensure participant is relaxed and abdominal muscles are relaxed.

4.1.4. Blood samples

Venous and capillary blood samples are obtained after an overnight fast of at least 8 hours (8–12 hours). Serum samples are handled according to assay specifications and stored at −80° C until analyzed at the end of the 18-month intervention. Point of care values are measured at each visit for HbA1c and glucose. At the end of the trial, serial samples for each participant will be analyzed for insulin, and lipid profile including triglyceride concentrations.

4.2. Physical Activity and Dietary Behaviors

4.2.1. Physical Activity

An objective measure of physical activity is obtained at baseline prior to randomization, and in association with each in-person checkpoint visit, through the wearing of an ActiGraph activity monitor (wGT3X-BT) for a 7-day period. The 7-day period occurs prior to randomization at baseline, and in the assessment window for the follow-up assessments, which may occur prior to or after the assessment visit based on scheduling availability of the participant. Each participant wears the monitor on his/her waist, at the tip of the iliac crest of the right hip. ActiGraph wear-time is validated by trained research assistants. A target is set for valid wear-time, which is considered at least 600 minutes per day (waking hours). Only data that reached this threshold are counted. Additionally, a target of four out of seven days was set (53). If a participant failed to wear the device for the minimum required time, the participant repeated an additional wear-time period prior to being randomized into the study. A self-report measure of physical activity, the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) (54, 55) is also administered at each timepoint.

4.2.2. Dietary Behaviors

Prior to randomization and at each checkpoint visit, participants are prompted on three randomly selected days, via text message, to log into the Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour (ASA-24) Dietary Assessment Tool (Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute) (56) online platform and complete a midnight-to-midnight recall of all food and beverage consumed in the prior 24 hours. At least one ASA-24 must be completed prior to randomization and for each subsequent checkpoint visit.

4.3. Demographics and Questionnaires

Participants complete surveys at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months post randomization via computer, using REDCap electronic data capture (57). At baseline, demographic variables collected include sex, age/date of birth, gender, race/ethnicity, school and year in school, and type of housing. Participants respond to additional validated survey measures at all assessment time points, as outlined and described in Tables 2 and 6.

Table 6.

Survey measures and descriptions for behavioral, cognitive, and psychological assessment

| Construct | Survey Description |

|---|---|

| Perceived Stress (78) | A 10-item questionnaire assessing global measure of perceived stress, using a Likert-type scale (0 = never, 4 = very often). |

| Stress Management(79) | A 9-item survey with yes-no responses to assess stress management habits, adapted from the APA Stress in America report. |

| Sleep(80) | A scale assessing sleep initiation (how long to fall asleep), duration (average hours per night), and 10 questions assessing quality of sleep used in the Medical Outcomes Study (1 = none of the time, 6 = all of the time). |

| Physical Activity(54, 55) | International Physical Activity Questionnaires (IPAQ) Short Form to measure health-enhancing physical activities in daily life, assessing intensity, frequency, and duration. |

| Physical Activity Self-Efficacy(81) Weight Management Social Support(82) |

A 5-item Likert-type scale used to assess an individual’s confidence in own ability to exercise in varying situations. Using the Weight Management and Support Inventory (WMSI), this 26 item questionnaire assessed the frequency and subjective helpfulness of supportive behaviors for weight loss for participants (1 = never/not at all helpful, 5 = daily/extremely helpful). |

| Interpersonal Support(83) | Measures informational and emotional support, as well as communication styles, through 24 questions (8 per construct) with participants using a Likert scale of (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). |

| Metabolic Risk(8) | A 5-question (yes/no) survey to assess whether participants know about metabolic risk and about specific aspects of metabolic risk, as described by Huang et al. |

| Cigarettes/Tobacco Use and Weight Control (84, 85) | Cigarette use was assessed with the questions from the 2014 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, with an additional 3 questions from the Weight Control Smoking Scale (WCSS) to assess tobacco use and weight control (1 = not at all, 4 = very much so). |

| E-Cigarette Use, Perceptions, and Weight Control (84–86) | E-cigarette use was assessed based on items from the Wave 1 Adult Instrument from the Population Assessment on Tobacco and Health (PATH), with 3 questions adapted from the WCSS to assess e-cigarette use and weight control (1 = not at all, 4 = very much so). Additionally 11 questions were included from the PATH to assess perceptions of e-cigarettes (yes/no). |

| Social Media Engagement(87) | This 21-question survey assesses Facebook and SMS text message usage with a Likert scale for 11 questions based on Ellison et al. (2007) (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) and additional questions assessing Facebook group utilization. |

| Social Networking(88) | A three-question survey assessed the number of social contacts trying to lose weight (1 = none, 4 = all). |

| Social Norms(88) | A 8-item survey assessed social norms for obesity and obesity-related behaviors, including social acceptability of being overweight (1 = very unacceptable, 4 = very acceptable), frequency of contacts within networks encouraging and providing weight loss information (1 = never, 4 = often), and role models for healthy eating and activity. |

| Weight Self-Efficacy(89) | Participants reported on weight self-efficacy using the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire (WEL), a 20-question survey on confidence for situational factors related to weight loss (0 = not confident, 9 = confident). Situational factors include negative emotions, availability, social pressure, physical discomfort, and positive activities. |

| Body Image and Quality of Life(90) | The Body Image Quality of Life Inventory, a 19-question survey, assessed feelings about physical appearance (−3 = very negative effect, 3 = very positive effect). |

4.4. Sustainability and Implementation Metrics

Aim 3 of the project is to examine implementation feasibility and sustainability infrastructure on the campus communities. This portion of the project is informed by the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) (33) as the conceptual framework, which posits the public health potential of research clinical trials is incomplete without incorporating implementation outside the research study. This framework takes into consideration key features: 1) the Intervention from an Organizational perspective; 2) the Intervention from a Patient perspective; 3) the External Environment; 4) the Implementation and Sustainability Infrastructure (33). We have adapted the PRISM model (33) and will conduct qualitative interviews to assess how each applies to our program.

To examine implementation feasibility, we will evaluate implementation costs

Data collection will focus on intervention costs from a provider and participant perspective (58, 59). We anticipate these are the most relevant for decision makers contemplating adopting this intervention across college campus communities (60, 61). These perspectives allow us to evaluate the total costs to the provider (i.e., college) adopting the program, and to the consumer (i.e., student). Provider costs will be calculated by summing the total direct costs of delivering the intervention (e.g., personnel, program materials, text messaging fees) (58, 62). Individually attributable costs will be tracked by the participant (e.g., time spent in program activities, record keeping) (59, 62, 63). Indirect costs (e.g., space, utilities, technology development) of the intervention will be tracked separately and allocated post-hoc commensurate with the direct resources employed (64, 65). Coyle’s (66) recommendations and Public Health Service guidelines (67) will be used to guide our analytic plan.

4.5. Consumer Satisfaction

This measure, developed originally for use in the social media pilot RCT (26) was adapted for this trial. It includes a rating of participants’ satisfaction with the program, treatment materials, and duration and frequency of intervention delivery. Participants will rate the degree to which the program was helpful useful for meeting weight-related targets.

5. Participant Safety

The following steps and safeguards are being implemented to monitor the safety of the participants.

As baseline and all follow-up time points participants’ weight and general health status are entered into a secure online database. Notes are made by the project team regarding any out-of-range values for which health provider clearance is needed.

Given the online nature of the intervention delivery, we implemented a few safeguards related to weight loss that is too rapid. For example, an automatic alert is triggered to the study team if a Tailored research participant loses (or gains) more than 3 pounds in a week. Upon receipt of a weight change alert, a member of the research team reviews the participant’s profile, including time in study, weight change history, and sends an applicable response based on the magnitude of change and frequency of alerts. Since the Targeted participants are not texting specific weight loss numbers on a weekly basis, a series of monthly texts were implemented as an additional safeguard. Participants in the two weight loss groups are asked to report on whether their weight loss meets, exceeds, or is less than the study goals of 1–2 pounds per week.

On a monthly basis, participants respond to a text as to any changes in their health status over the last month. The study team receives an alert to check in with those participants who indicate yes.

During weekly project meetings, study staff discusses the alerts and the appropriate staff member and action to be followed. Participant history and study progress are reviewed as needed.

At the 6, 12, and 18 month follow-up visits, participants’ weight change progress is assessed and new goals are set as needed. Study participant questionnaires, are reviewed as part of the wrap up protocol for the visits.

During the screening process, both the AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification test)(68) alcohol tool is administered as is an inquiry about history of substance dependence or abuse. Participants indicating harmful or concerning use are provided with appropriate resources.

At the beginning of the trial (as part of the screening process), and at the 18 month follow-up, the Eating Disorders Diagnostic Scale (69) is administered. Any concerns related to severe eating pathology are reported to the PIs, and relevant resources are sent to the participant.

Weekly monitoring, training, and protocol review occurs within and cross-site with any issues related to data collection, or safety reported to the PIs.

On at least a quarterly basis, study investigators meet to discuss any data collection and/or safety issues.

6. Analytic Plan

The first primary statistical hypotheses are that relative weight loss over the 18-month follow-up will be greater for the Tailored group compared with the Targeted group, and that both groups will show greater weight loss than the Control group. This will be tested using mixed linear models for longitudinal data. Change is not expected to be linear through the follow-up. For example, there may be a pattern of weight loss followed by regain. Therefore, graphical and statistical approaches to curve-fitting will be used to identify a transformation, such as a polynomial model, that provides a reasonably good fit to individual time trends. This analysis will be blinded to study group to avoid biased selection of transformations that would maximize between group differences. In the event of very poor fit for both linear and non-linear transformations, the primary hypotheses will be tested using analysis of covariance, repeated for the 6, 12, and 18-month follow-up times. Study site, baseline BMI, school year, and sex will be included as covariates. Also, season will be included as a time-varying covariate for longitudinal models. Pairwise contrasts among the three groups will be tested using the Bonferroni adjustment.

The primary statistical tests will use the intent-to-treat principle. Although this provides a strong test of the study hypotheses, it tends to underestimate the treatment effect for compliers. Thus, a secondary analysis will estimate the effect of each social media treatment for participants who were mostly compliant with their intervention. This will use the “complier average causal effect” (CACE) methodology and will be estimated through a two-stage least squares model (70). Participants will be classified as either low or medium-to-high compliers based on an index to be developed derived from percent of materials accessed and percent of text messages receiving a response. Because the CACE approach may have some degree of violation of the “exclusion restriction” assumptions related to the chosen cut point, a sensitivity analysis will examine how effect sizes change with different cut points.

For our second aim, testing the association between weight loss and change in metabolic risk factors, participants will be divided into one group who achieve a 5% weight loss at 6 and 18 months and a second group who do not achieve and maintain that weight target at both of those time points. For each risk factor at each time point, we will compare those who achieve the 5% weight target to those who do not meet this threshold and hypothesize that the first group will have significantly lower triglycerides, higher HDL cholesterol, and lower blood pressure than the second group. A repeated measures analysis of covariance for each outcome will test for both mean differences between these two groups and a Group × Time interaction, while controlling for treatment group and study site. Given the potential independent effect of physical activity on both weight loss and/or changes in these metabolic risk factors, further analyses will explore the association of physical activity with these outcomes.

For our third aim, related to the cost analyses, the average cost estimates per participant will be derived using a combination of stochastic and deterministic costing. The distribution of participant-level costs will be examined and transformed, as needed to approximate a normal distribution. Estimates of participant costs will be combined with provider costs to determine the cost of intervention implementation. Decision analytical models will be created using the estimated cost inputs, trial efficacy results, and other assumptions about program implementation (67, 71, 72). To compare the incremental benefit of being assigned to the Targeted or Tailored intervention, the Contact Control arm will be used as the reference group for calculating increments in treatment effectiveness (expressed in kg of weight loss and percentage of weight loss from baseline to 18 months) and cost (in dollars). Calculations of marginal costs per participant and per effect (e.g., cost per person, achieving thresholds of weight loss [5%]) will be done using the TreeAge Healthcare software package,(73) which permits modeling of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER), and Monte Carlo simulation to generate confidence intervals around the cost-effectiveness estimates. Confidence intervals will be estimated using both bootstrap and Fieller theorem methods.(74) We will conduct sensitivity analyses to determine the impact on cost estimates due to variability in key parameters (e.g., intervention development costs, wages, participant time).(75)

Statistical power for the primary aim was approximated through an analysis of covariance model where each outcome is measured at the follow-up time and the baseline measure is included as a covariate. Power analysis parameters were chosen based on estimates from our pilot study within the context of clinically meaningful losses. Calculations assumed a desired power of .80, a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of .016 for each contrast of two groups, 2-sided tests, a baseline to follow-up correlation of .91, and an unadjusted standard deviation of 12 kg. Although we would expect a mean weight advantage of at least 5 kg compared with the Contact Control Group at some follow-up timepoints, we have estimated power to detect a smaller difference at the 18 month timepoint, which would likely correspond to the timepoint with the most weight regain. The 2.1 kg difference would correspond to a difference, for example, in the Tailored treatment group of 4.2 kg (approximately 5% of body weight, a clinically meaningful difference) compared with 2.1 kg in the Targeted group and the control group remaining weight stable. To detect a difference of 2.1 kg between any two groups, the resulting sample size per group was 121. With a projected attrition rate of 19% at 18 months, based on previous studies (76, 77), we will need to recruit 450 participants.

Differential attrition by study group is a threat to the validity of any clinical trial. The standard mixed model growth model approach we proposed as the primary analytic method for the first aim will allow for incorporation of all available follow-up data points and produce unbiased estimates of treatment effect under the Missing at Random assumption. It is possible this assumption will be violated if, for example, participants who gain a lot of weight drop out because of embarrassment or disenchantment with the study. Therefore, we will carefully examine missing data patterns, and supplement the mixed model approach with sensitivity analyses.

7. Discussion

Healthy Body Healthy U is a randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of two weight loss interventions compared to a contact control across two university settings. University students between the ages of 18–35 are randomly assigned to one of the three treatment arms. All three arms of the study receive their content via Facebook, text messaging, and weekly reports via pre-programmed, automated feedback. The two weight loss arms, Tailored and Targeted, both receive the same weight loss content. Tailored arm receives additional personalized feedback including text messages based on their own high-risk behaviors related to weight loss, as well as text message inquiries the responses to which populate their personalized, tailored feedback report. The Targeted group also receives a feedback report but it contains summative, not personalized, information. The Contact Control group receives wellness content related to maintaining a healthy body weight (body image, energy, and stress management information) via the same delivery channels as the Tailored and Targeted arms.

Thus, the primary aim is to evaluate the efficacy of the interventions for weight loss. It is hypothesized that the Tailored intervention will realize greater weight loss than the Targeted intervention and that both the Tailored and Targeted interventions will lose more weight than the Contact Control group. The secondary aim is to evaluate changes in metabolic risk factors among those participants who have maintained at least 5% weight loss at 18 months. The third aim is to conduct formative work to evaluate the feasibility of implementing the interventions on college campuses, including an assessment of costs as well as the sustainability infrastructure using the PRISM model (33). The automation of the intervention content, which includes both posting content to Facebook as well as pre-programmed text messages allows for this type of program to be scalable. While there is an upfront cost related to platform development, this will be examined in future analyses related to cost, particularly if there is a threshold needed of number of participants to recoup costs, as well as cost per unit of weight improvement.

Programs to promote healthy body weight during young adulthood are critical in that young adulthood represents a window of increased risk for overweight/obesity and all of the health sequelae, such as an increased risk for cardiometabolic dysfunction, which can accompany such increases in weight (1–4, 7, 8). This period of young adulthood is also marked by high engagement in and use of social media (13–15). Thus, creating a weight loss intervention for young adults utilizing delivery channels with which they are already familiar and are already incorporated into their daily life, could be an effective means of reaching these emerging adults. We will reach students through their university campuses, giving the social media platforms an environmental context that could enhance social networking with peers in the programs.

The design has numerous noteworthy strengths. First, the three-group design will allow for comparisons between active weight loss interventions as well as between a contact control. Second, the intervention is grounded in evidence-based interventions in that it was based on a successful pilot (26), as well as adapting the Diabetes Prevention Program (49, 50) for university students. Third, strength to the study design is that HBHU uses theory-based strategies for behavior change. Specifically, the social cognitive theory principles of self-monitoring, planning, goal setting and feedback, all of which influence self-regulatory skills and are designed to create mastery experiences to increase self-efficacy (45) or healthy eating, portion control, and physical activity. In addition, HBHU is utilizing and testing the Dual Path of Influence Model (46) from Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (39), which proposes that behavior change can be influenced by one’s use of social media technology in the environment and social support. Fourth, the delivery of the evidence-based programs is done via social media which allows the students to engage with the content on their own time in their own way rather than coming to scheduled in-person group meetings. Fifth, we are also collecting venous and point of care blood measures to test the little known metabolic health and effectiveness of weight loss interventions in university students. Sixth, the automated aspects of this intervention allow the development of content that mirrors a face-to-face intervention in the quality of the content presented. However, unlike face-to-face interventions this automation reduces person-power so that it has the potential to be disseminated more easily if found to be effective. Finally, another important aspect to the study design is that we will be testing the cost, feasibility, and sustainability of the program within the university setting. Thus, we will determine if the added cost and participant burden to tailor materials to the individual are cost effective for the weight loss outcomes. It could be that the Targeted intervention could have a larger public health impact if it is found to be easier to deliver and therefore easier to disseminate.

In summary, Healthy Body Healthy U, offers an eHealth approach to weight loss for technology savvy young adults who are at risk for increased weight gain and the resulting health effects in this critical window. The intervention materials are evidence-based, adapted to university students, theoretically sound and will test if tailoring of materials outperforms targeting and if both weight loss groups outperform a contact control. In addition to this rigorous design, the HBHU study will be examining important issues of translation and sustainability of the program through cost effectiveness analyses and qualitative interviews so that more is known about how to successfully implement effective weight loss programs in the university setting.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the undergraduate and graduate student research assistants who contributed to the project, in particular: Denise Aske, Breanne Dowdie, Heather Harker-Ryan, Katrina Hufnagel, Mira Kahn, Madeline Kirch, Juliet Schear, Jennifer Schindler-Ruwisch, Caitlin Sirianni, Judith Tauriac, Lauren Winters. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01DK100916. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Williamson DF, Kahn HS, Remington PL, Anda RF. The 10-year incidence of overweight and major weight gain in US adults. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(3):665–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(219):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obesity Reviews. 2004;5:4–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang TT, Shimel A, Lee RE, Delancey W, Strother ML. Metabolic Risks among College Students: Prevalence and Gender Differences. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2007;5(4):365–72. doi: 10.1089/met.2007.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang TT, Kempf AM, Strother ML, Li C, Lee RE, Harris KJ, et al. Overweight and components of the metabolic syndrome in college students. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):3000–1. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greaney ML, Quintiliani LM, Warner ET, King DK, Emmons KM, Colditz GA, et al. Weight management among patients at community health centers: The “Be Fit, Be Well” study. Obesity and Weight Management. 2009;5(5):222–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenhart A. Cell phones and American adults: They make just as many calls, but text less often than teens. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center; 2010. [Available from: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Cell-Phones-and-American-Adults.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pew Internet Research. Cell Phone Data Set. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2010. [Available from: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Cell-Phones-and-American-Adults.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aleman AM, Wartman KL. Online Social Networking on Campus: Understanding what matters in student culture. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Facebook. Do you know what’s up? Check out these 2013 social media statistics. 2013 [updated January 27. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/notes/up-creative-inc/do-you-know-whats-up-check-out-these-2013-social-media-statistics/470970089631080.

- 14.Statistica. Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide as of 3rd quarter 2016. 2016 [Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/

- 15.Pew Internet Research. Mobile Messaging and Social Media 2015. 2015 [Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/19/mobile-messaging-and-social-media-2015/

- 16.Pew Internet Research. US Smartphone Use in 2015. [Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015/

- 17.Tate DF, Wing RR, Winett RA. Using Internet technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(9):1172–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tate DF, Zabinski MF. Computer and Internet applications for psychological treatment: update for clinicians. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;60(2):209–20. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neve M, Morgan PJ, Jones PR, Collins CE. Effectiveness of web-based interventions in achieving weight loss and weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2010;11(4):306–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagoto SL, Waring ME, Schneider KL, Oleski JL, Olendzki E, Hayes RB, et al. Twitter-Delivered Behavioral Weight-Loss Interventions: A Pilot Series. JMIR research protocols. 2015;4(4):e123. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner-McGrievy G, Tate D. Tweets, Apps, and Pods: Results of the 6-month Mobile Pounds Off Digitally (Mobile POD) randomized weight-loss intervention among adults. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e120. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinberg DM, Tate DF, Bennett GG, Ennett S, Samuel-Hodge C, Ward DS. The efficacy of a daily self-weighing weight loss intervention using smart scales and email. Obesity. 2013;21(9):1789–97. doi: 10.1002/oby.20396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yon BA, Johnson RK, Harvey-Berino J, Gold BC. The use of a personal digital assistant for dietary self-monitoring does not improve the validity of self-reports of energy intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(8):1256–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke LE, Wang J, Sevick MA. Self-Monitoring in Weight Loss: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(1):92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spring B, Duncan JM, Janke E, et al. Integrating technology into standard weight loss treatment: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173(2):105–11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Napolitano MA, Hayes S, Bennett GG, Ives AK, Foster GD. Using Facebook and text messaging to deliver a weight loss program to college students. 2013;21(1):25–31. doi: 10.1002/oby.20232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Center for Education Statistics. Postbaccalaureate Enrollment [Internet] 2016 [cited November 3, 2016]. Available from: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_chb.asp.

- 28.National Center for Education Statistics. Undergraduate Enrollment [Internet] 2016 [cited November 3, 2016] Available from: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cha.asp.

- 29.Lynch S, Hayes S, Napolitano M, Hufnagel K. Availability and Accessibility of Student-Specific Weight Loss Programs and Other Risk Prevention Health Services on College Campuses. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2(1):e29. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svetkey LP, Batch BC, Lin PH, Intille SS, Corsino L, Tyson CC, et al. Cell phone intervention for you (CITY): A randomized, controlled trial of behavioral weight loss intervention for young adults using mobile technology. Obesity. 2015;23(11):2133–41. doi: 10.1002/oby.21226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tate DF, LaRose JG, Griffin LP, Erickson KE, Robichaud EF, Perdue L, et al. Recruitment of young adults into a randomized controlled trial of weight gain prevention: message development, methods, and cost. Trials. 2014;15:326. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allman-Farinelli M, Partridge SR, McGeechan K, Balestracci K, Hebden L, Wong A, et al. A Mobile Health Lifestyle Program for Prevention of Weight Gain in Young Adults (TXT2BFiT): Nine-Month Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(2):e78. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(4):228–43. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Candadian Society for Exercise Physiology. PAR-Q and You. Gloucester, Ontario, Canada: 1994. Gloucester, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(Suppl 3):S227–32. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Glassman B. One size does not fit all: the case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(4):276–83. doi: 10.1007/BF02895958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skinner CS, Campbell MK, Rimer BK, Curry S, Prochaska JO. How effective is tailored print communication? Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(4):290–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02895960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):673–93. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentiss-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinto AM, Gokee-Larose J, Wing RR. Behavioral approaches to weight control: a review of current research. Women’s Health (London, England) 2007;3(3):341–53. doi: 10.2217/17455057.3.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foster GD, Makris AP, Bailer BA. Behavioral treatment of obesity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;82(1 Suppl):230S–5S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.230S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wing R. Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity. In: Bray G, Bouchard C, editors. Handbook of Obesity: Clinical Applications. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare; 2008. pp. 147–68. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandura A. The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist. 1978;33(4):344–58. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. The American Psychologist. 1989;44(9):1175–84. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, Makris AP, Rosenbaum DL, Brill C, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:147–57. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00005. United States. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foster GD, Borradaile KE, Sanders MH, Millman R, Zammit G, Newman AB, et al. A randomized study on the effect of weight loss on obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes: the Sleep AHEAD study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1619–26. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The Diabetes Prevention Program Resarch Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2165–71. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The Diabetes Prevention Program. Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(4):623–34. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Examination Protocol. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, Kelley DE, Leibel RL, Nonas C, et al. Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: a consensus statement from Shaping America’s Health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, The Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(5):1197–202. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matthews CE, Hagstromer M, Pober DM, Bowles HR. Best practices for using physical activity monitors in population-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(1 Suppl 1):S68–76. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182399e5b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hagstromer M, Oja P, Sjostrom M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(6):755–62. doi: 10.1079/phn2005898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2003;35(8):1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Cancer Institute. Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Recall (ASA24)-2014 [Internet] National Cancer Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krukowski RA, Tilford JM, Harvey-Berino J, West DS. Comparing behavioral weight loss modalities: incremental cost-effectiveness of an internet-based versus an in-person condition. Obesity. 2011;19(8):1629–35. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hernan WH, Brandle M, Zhang P, Williamson DF, Matulik MJ, Ratner RE, et al. Costs associated with the primary prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(1):36–47. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gold MR, Siegel J, Russell LB, Weinstein MC, editors. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drummond MF, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perri MG, Limacher MC, Durning PE, Janicke DM, Lutes LD, Bobroff LB, et al. Extended-Care Programs for Weight Management in Rural Communities. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(21):2347–54. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tate D, Finkelstein E, Khavjou O, Gustafson A. Cost effectiveness of internet interventions: review and recommendations. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;38(1):40–5. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9131-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaplan RS, Atkinson AA. Advanced Management Accounting. 3rd. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baker JJ. Activity-Based Costing and Activity-Based Management for Health Care. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publication; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coyle D. Statistical analysis in pharmacoeconomic studies. A review of current issues and standards. Pharmacoeconomics. 1996;9(6):506–16. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199609060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gold MR, Siegel J, Russell LB, Weinstein MC. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M, World Health Organization AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stice E, Telch CF, Rizvi SL. Development and validation of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: a brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(2):123–31. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stuart EA, Perry DF, Le HN, Ialongo NS. Estimating intervention effects of prevention programs: accounting for noncompliance. Prev Sci. 2008;9(4):288–98. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0104-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petitti DB. Meta-analysis, decision analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis: Methods for quantitative synthesis in medicine. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hayes SC, Brownstein AJ, Haas JR, Greenway DE. Designing and conducting cost-effectiveness analyses in medicine and health care. Instructions, multiple schedules, and extinction: Distinguishing rule-governed from schedule-controlled behavior. J Exp Anal Behav. 1986;46(2):137–47. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1986.46-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.TreAge Healthcare Module. Williamstown, MA: Treeage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Polsky D, Glick HA, Wilke R, Schulman K. Confidence intervals for cost–effectiveness ratios: a comparison of four methods. Health Economics. 1997;6:243–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199705)6:3<243::aid-hec269>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]