Abstract

Tissue engineering has emerged as a viable approach to treat disease or repair damage in tissues and organs. One of the key elements for the success of tissue engineering is the use of a scaffold serving as artificial extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM hosts the cells and improves their survival, proliferation, and differentiation, enabling the formation of new tissue. Here, we propose the development of a class of protein/polysaccharide-based porous scaffolds for use as ECM substitutes in cardiac tissue engineering. Scaffolds based on blends of a protein component, collagen or gelatin, with a polysaccharide component, alginate, were produced by freeze-drying and subsequent ionic and chemical crosslinking. Their morphological, physicochemical, and mechanical properties were determined and compared with those of natural porcine myocardium. We demonstrated that our scaffolds possessed highly porous and interconnected structures, and the chemical homogeneity of the natural ECM was well reproduced in both types of scaffolds. Furthermore, the alginate/gelatin (AG) scaffolds better mimicked the native tissue in terms of interactions between components and protein secondary structure, and in terms of swelling behavior. The AG scaffolds also showed superior mechanical properties for the desired application and supported better adhesion, growth, and differentiation of myoblasts under static conditions. The AG scaffolds were subsequently used for culturing neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, where high viability of the resulting cardiac constructs was observed under dynamic flow culture in a microfluidic bioreactor. We therefore propose our protein/polysaccharide scaffolds as a viable ECM substitute for applications in cardiac tissue engineering.

Keywords: alginate, gelatin, collagen, biomimetic scaffold

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, tissue engineering has emerged as a new approach to treat disease or damage in tissues and organs. Tissue engineering strategies combine cells with biomaterial scaffolds in such a way that, under appropriate conditions, the growth of new healthy tissues can be supported and promoted. The therapeutic potential of engineered tissues is particularly significant for those tissues that cannot regenerate spontaneously or be replaced by synthetic prostheses, such as the ischemic myocardium.1,2 One of the key elements for the success of tissue engineering is the use of a scaffold, that hosts the cells and improves their survival, proliferation, and differentiation, thus functioning as an artificial extracellular matrix (ECM) until new tissue is formed by the residing cells.

In healthy human tissues, the ECM is a complex meshwork in which most of normal anchorage-dependent cells reside. This matrix provides structural support for the cells to attach, grow, migrate, and respond to signals, and may act as a reservoir to provide bioactive cues for regulation of cellular activities.3,4 For example, in the case of cardiac tissue, ECM serves as an anisotropic structural scaffold to guide aligned cellular distribution and organization. It accommodates contraction and relaxation of cardiomyocytes and facilitates force transduction, electrical conductance, intracellular communication, and metabolic exchange within the myocardial environment.

In this sense, it would be desirable that the 3D scaffolds used to repair the target tissues act as artificial ECMs mimicking the composition and functions of their native counterparts. In general, ECMs are mainly composed of proteoglycans, which are long-chain polysaccharides, and fibrous proteins, including collagen, elastin, fibronectin, and laminin.3,4 In particular, the cardiac ECM surrounds and supports myocardial cells, that is, cardiomyocytes cardiac fibroblasts, and vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. The main components include structural proteins such as elastin and collagen type I, adhesive proteins such as fibronectin, laminin, and collagen type IV, as well as anti-adhesive proteins and proteoglycans.5–7 It has been shown that the composition of the cardiac ECM may affect phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of cardiac cells.7

Polymers are widely investigated to produce scaffolds for tissue engineering. In particular, polymers of natural origin that are typical ECM components have been extensively adopted in scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering (CTE).8–12 Therefore, a scaffolding system where a protein component blends with a polysaccharide component, mimicking composition and interactions in the native ECM, would be a logical design to guide the division, growth, and development of residing cells. In the past few years, the design of scaffolds based on blends of proteins and polysaccharides, as surrogates of the native ECM, has emerged as a valuable strategy for tissue engineering applications. Scaffolds mimicking the chemical composition of native ECM have been investigated for the regeneration of skin,13 cornea,14 peripheral nerve,15 cartilage,16,17 bone,18,19 and for tissue engineering applications in general.20–22

Several tissue engineering studies have focused on fabricating biodegradable and biocompatible scaffolds mimicking the anisotropy and microarchitecture of their native counterparts.23–25 Materials based on blends of proteins and polysaccharides have been proposed as scaffolds as well.26–28 However, the properties of these systems have never been compared with their natural counterparts.

This work aimed at the development and characterization of a new type of protein/polysaccharide-based scaffolds for their use as cardiac ECM substitutes. These scaffolds mimicking the ECM composition were based on blends of a protein component, collagen or gelatin, with a polysaccharide component, alginate. In our previous research, a screening of alginate/gelatin (AG) blends with different weight ratios was performed.29 A blend with 20:80 weight ratio between polysaccharide and protein components showed the best results for application in CTE. Therefore, AG and alginate/collagen (AC) blends with a 20:80 weight ratio were used to produce porous scaffolds using a freeze-drying technique in the current work. The morphological, physicochemical, functional, mechanical, and biological properties of these scaffolds were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), infrared (IR) chemical imaging, swelling test, in vitro degradation assessment, and biological responses with a focus on myoblasts and cardiomyocytes. Comparisons were further carried out between our new scaffolds and the decellularized natural porcine myocardial tissue we had previously optimized.24

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Alginate (viscosity of 2% solution at 25°C = 250 cps), collagen type I, gelatin (type B from bovine skin), glutaraldehyde (GTA; 25% aqueous solution), phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and collagenase were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). Calcium chloride and acetic acid were purchased from Carlo Erba Reagenti (Milan, Italy). The reagents were all analytical grade and used as received.

Preparation of sponges

Aqueous solutions of alginate and gelatin 2% (w/v) were individually prepared at 50°C. Collagen was dissolved in 0.5 M acetic acid (pH = 2.5) under mild stirring in an ice bath, at 1% (w/v) concentration. The alginate solution was mixed with the gelatin or collagen solution under stirring at room temperature to produce AG and AC blends. Both blends had a 20:80 weight ratio between polysaccharide and protein components according to our previous optimization.29 Therefore, in the final forms, the weight percentages of the polysaccharide and the proteins were fixed to allow for comparisons. Before mixing with alginate, the collagen solution was conditioned with sodium hydroxide to pH = 6, to avoid the formation of a precipitate. The mixtures (10 mL) were poured into polystyrene Petri dishes and then freeze-dried to produce sponges.

The sponges were treated with GTA vapours to crosslink the protein component. Crosslinking was performed by affixing the sponges to the top of a sealed vessel, containing 30 mL of an 8% GTA (v/v) water solution at the bottom. The container was placed in an oven at 37°C for 8 h. Then the samples were treated with Ca2+ ions to crosslink the alginate component, by incubating them in 10 mL of a 2% (w/v) CaCl2 aqueous solution for 1 h. Subsequently, the samples were immersed for 16 h in a coagulation bath consisting of 0.5 M acetic acid solution at a pH value of 2.5, to promote the electrostatic interactions between the amino groups of the protein with the carboxylic groups of the polysaccharide. GTA and acetic acid may exert toxic effects on the cells, but it is known that the residual molecules of these agents can be effectively removed by extensive rinsing.30,31 The crosslinked sponges were therefore washed thoroughly with water to remove excessive GTA and acetic acid, until UV spectrophotometric and pH analysis of the wash did not reveal GTA and acetic acid traces. Finally, the sponges were dried again by freeze-drying.

Preparation of decellularized myocardial tissue samples

Small myocardium samples were excised and dissected from the mid-layer of the lateral wall of the left ventricle of a porcine heart. We followed a decellularization protocol from the literature.24 Briefly, the samples were washed three times for 45 min using a hypertonic solution (1.1% w/v NaCl). Three cycles of centrifugation in trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were carried out (40 min at 200 rpm; 60 min at 240 rpm; and 80 min at 350 rpm). An additional centrifugation step (50 min at 350 rpm) in a hypertonic solution (3% w/v NaCl) was subsequently performed. Finally, the samples were washed three times in a physiologic solution (0.9% w/v NaCl) for 20 min and freeze-dried.

Morphological analysis

Analyses of scaffold porosity and morphology were carried out by SEM (JSM 5600, Jeol Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) on samples sputter-coated with gold. The percentage of porosity and the average pore size were measured analyzing SEM images by the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The percentage of porosity was calculated from the ratio between the pore area and the total scaffold area.

IR chemical imaging analysis

An IR analysis was carried out with a Spectrum Spotlight 350 FT-NIR imaging system (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Attenuated total reflectance (ATR) Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was performed to evaluate the major absorption bands of the components in the scaffolds.32 All spectra were obtained at 2 cm−1, representing the average of 16 scans.

To analyze the chemical homogeneity of the samples, spectral images were acquired using an IR imager in the 4000–600 cm−1 range. The spatial resolution was 100 × 100 μm2 in the reflectance (μATR) mode and 6 μm in the transmission mode. Background scans were obtained from blank regions without samples. Infrared images were acquired with a liquid nitrogen-cooled mercury cadmium telluride line detector composed of 16 pixel elements. Spectra from the surface of a sample were collected by placing the ATR objective on the sample in contact mode. The Spotlight software was used for both acquisition and post-acquisition processing. The medium spectrum as defined by the instrument, which is the most representative spectrum of the chemical map, was recorded. Then, the correlation map was elaborated as the correlation between the chemical map and the medium spectrum. A correlation index close to 1 was considered indicative of the chemical homogeneity of the sample. Using the instrument software, second derivative spectra were also acquired, to study Amide I deconvolution.

Swelling test

Swelling tests were done by exposing the scaffolds to water vapor at 37°C. The swelling ratio of each sample was calculated using the equation: (Ws−Wd)/Wd×100, where Ws and Wd are the swollen weight and the dry weight of each sample, respectively. The experiments were continued until the samples reached constant weights, indicating equilibrium water uptake.

In vitro degradation

In vitro degradation was assessed in both PBS and in PBS supplemented with collagenase at 16 U/mL, in an agitated bath at 37°C. Weight losses of the scaffolds were measured. The percentage of weight loss was calculated according to the equation: (Wo−Wt)/Wo×100, where Wo is the starting dry weight and Wt is the dry weight at time t.

Mechanical characterization

Mechanical characterization of the scaffolds was carried out using a dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA8000, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). Scaffolds were cut in the form of rectangular strips (18 mm in length and 5 mm in width, thickness dependent on the material type). The thickness of the samples was measured at five different locations by using a caliper. The average value was used to assess the cross-sectional area. Since the scaffold should work in the human body in a moist environment, tests were performed under wet conditions. Before testing the samples, they were equilibrated for 3 h in PBS at 37°C and during the analysis they were maintained under wet conditions. The samples were further characterized in a bending configuration, the single cantilever mode. The storage modulus (E′) and the loss modulus (E″) were evaluated by performing a single strain (with an amplitude of 10 μm), multi-frequency (1, 3.5, and 10 Hz) test. These frequencies were chosen to reproduce healthy human heart rate (1 Hz, corresponding to 60 bpm), pathological human heart rate (3.5 Hz, corresponding to 210 bpm), and a fatigue condition with a supraphysiological pulse rate (10 Hz). The tests were carried out at 37°C.

Cell culture

C2C12 myoblasts were purchased from the European Collection of Cell Culture (London, UK). Sponges were sterilized using a standard protocol.29 Briefly, dry samples, cut into 1 cm2 squares, were washed with 70% ethanol followed by UV exposure for at least 15 min on each side. The sterilized scaffolds were placed in the individual wells of a 24-well plate and seeded with C2C12 cells at a density of 105 cells/well. The cells were also directly cultured in the wells of the plates as control. Cell proliferation test was performed using growth medium of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Cambrex, Italy) containig high glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, and penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL, all from Cambrex, Italy). Myogenic differentiation was induced by culturing the samples in DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum. Cultures were maintained in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C for up to 8 days. The medium was replaced every 2 days.

Proliferation and differentiation analyses

Cell numbers in the scaffolds were evaluated at 1, 3, and 7 days after seeding by staining the cells with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich). Cell differentiation was evaluated as actin filament elongation at 2, 5, and 8 days after seeding. Culture medium was removed and the scaffolds with attached cells were rinsed twice with PBS for 10 min each. The cells were immediately fixed by incubation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C. The fixed cells were first incubated with rhodamine-phalloidin in PBS (1:40) for 1 h and then washed three times with PBS. Subsequently, they were incubated with DAPI for 2 min to counterstain the nuclei. All these procedures were carried out in the dark. Images were obtained using a fluorescent microscope.

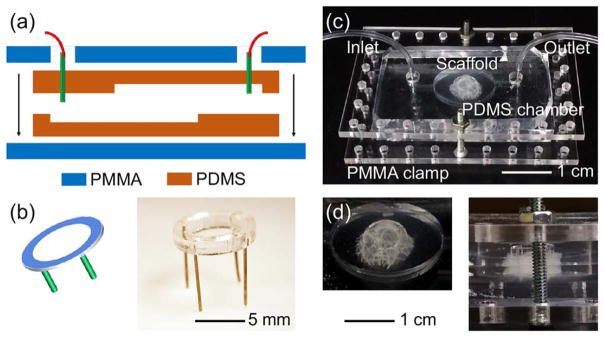

Construction of cardiac bioreactor

The scaffolds were cut into disks with a diameter of 10 mm and a thickness of 2 mm. Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were isolated from 2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats following our established protocol approved by the Institute’s Committee on Animal Care.33 The cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10 vol % FBS. Each scaffold was placed in a well of a 12-well plate and seeded with 4 × 106 cells by dropping a suspension of cells in 30 μL of medium. The medium containing the cardiomyocytes immediately wetted the scaffold via capillary action ensuring a uniform distribution of the cells inside the scaffold. Every 30 min, 10 μL of medium was introduced around the scaffold to maintain the moisture and prevent the cells from dehydration. The cells were allowed to attach to the matrix of the scaffold for 1 h, followed by addition of 1 mL of medium to cover the scaffold. The medium was changed every day during the first 3 days of culture.

The bioreactors were designed and fabricated according to our recently developed protocol.34 A laser cutter was used to cut off a poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) positive mold with an elliptical shape and a straight tail. The mold was taped to the bottom of a 10-mm petri dish, and filled with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) prepolymer mixture (10:1 ratio). After curing of PDMS at 80°C for 24 h, the elastomer was peeled off from the PMMA mold to achieve the negative chamber/channel complex. Two such PDMS structures were placed against each other to construct the bioreactor, where the inlet/outlet were punched for connection with external metal connectors and Teflon tubing. To prevent potential leakage, the PDMS device was further clamped in between a pair of PMMA slides held together by four screw/bolt sets. The scaffold was secured at the bottom of the chamber of a bioreactor by fixation using a custom-designed holder constructed from a ring of PMMA board with four metal legs. The bioreactors were filled with media and the tubing from the inlet/outlet was connected into a closed loop. A peristaltic pump was used to drive the liquid at a flow rate of 200 μL/h.

The viability of the cardiomyocytes inside the scaffolds under both static and dynamic conditions was evaluated at days 3, 7, and 14 post seeding using the Live/Dead viability kit (ThermoFisher, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analyses

Results were reported as means ± SDs. The Student’s t test was used to determine p values and to assess statistical significance. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05, p <0.01, and p <0.001.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Morphological analysis

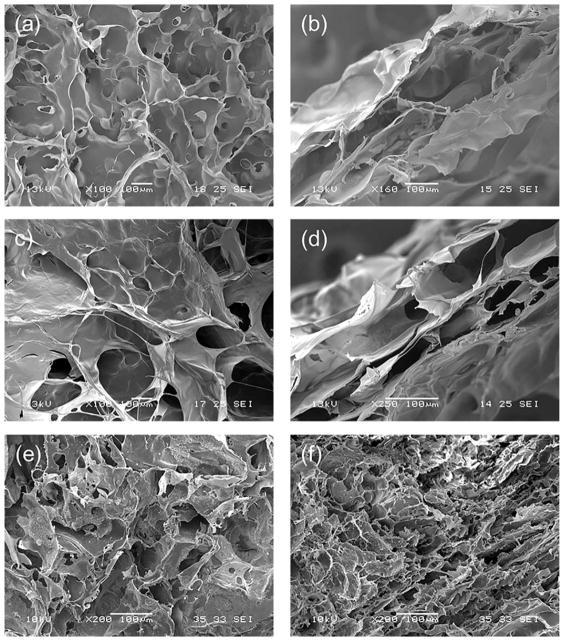

One of the main requirements for tissue engineering scaffolds is high porosity coupled with interconnectivity of pores, to promote cell seeding and growth, preserve tissue volume, and facilitate the circulation of nutrients and waste products.35 To evaluate the morphological characteristics of both sponges and decellularized porcine myocardium, SEM images were acquired. Both AC and AG sponges showed a highly porous and homogeneous structure with well-interconnected pores [Fig. 1(a,c)]. A very similar surface porosity was observed for the decellularized myocardium [Fig. 1(e)], while the interior pores were smaller for the native tissue [Fig. 1(f)] than for the prepared scaffolds [Fig. 1(b,d)]. The average pore sizes were 154 ± 24 μm for the AC sponges, 198 ± 58 μm for the AG sponges, and 56 ± 10 μm for the native tissue. The percentages of porosity, as calculated by ImageJ analysis of SEM images, was 49% for the AC sponges, 60% for the AG sponges, and 13% for the native tissue. The higher porosity of sponges with respect to native tissue can be considered an advantage for promoting cell infiltration and colonization, thus favoring tissue regeneration.

FIGURE 1.

SEM micrographs of: (a) surface and (b) cross-section of AC sponge; (c) surface and (d) cross-section of AG sponge; and (e) surface and (f) cross-section of decellularized porcine myocardium.

FT-IR chemical imaging analysis

Infrared analysis is an important tool to evaluate the chemical composition and homogeneity and to investigate interactions at the molecular level between scaffold components. Molecular interactions between proteins and polysaccharides in native tissues play important roles in the normal physiology of animals and humans.36 Similarly, molecular interactions within a scaffold have a significant impact on cellular response.37 Therefore, the study of these interactions is fundamental in the selection of the best components for the production of cell substrates with improved performance. The FT-IR spectra of AG and AC scaffolds were acquired and compared with the spectrum of the native tissue. Results are reported in Table I. The typical absorption peaks of pure polymers, used in the preparation of the scaffolds, are:

TABLE I.

FT-IR Analysis

| COO− (cm−1) | C-O-C (cm−1) | Amide I (cm−1) | Amide II (cm−1) | Amide III (cm−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | 1587 | 1027 | |||

| Collagen | 1636 | 1541 | 1236 | ||

| Gelatin | 1630 | 1539 | 1235 | ||

| AC scaffold | 1029 | 1632 | 1546 | 1234 | |

| AG scaffold | 1034 | 1634 | 1540 | 1240 |

Wavelength displacements in AC and AG scaffolds for the typical absorption bands of alginate, gelatin, and collagen.

1587 cm−1 (COO−) and 1027 cm−1 (C-O-C) for alginate;

1630 cm−1 (Amide I), 1539 cm−1 (Amide II) and 1235 cm−1 (Amide III) for gelatin;

1636 cm−1 (Amide I), 1541 cm−1 (Amide II) and 1236 cm−1 (Amide III) for collagen.38

Absorption peaks for gelatin and collagen are obviously similar since gelatin is obtained by collagen denaturation.

The FT-IR spectrum of the AG scaffolds showed the presence of the typical absorption peaks of both polymers. Moreover, in the AG blend some of the typical absorption peaks of alginate and gelatin were found to shift toward slightly higher frequencies compared with the pure components. This suggests the formation of hydrogen bonds between the protein and the polysaccharide, as reported in the literature.13,29,39 The FT-IR spectrum of the AC scaffolds confirmed the presence of both components as well. As detailed in Table I, small band displacements were observed only for Amide I and II typical absorption peaks. This suggests that in AG scaffolds gelatin, thanks to its higher conformational flexibility than collagen, can interact more easily with the polysaccharide component.

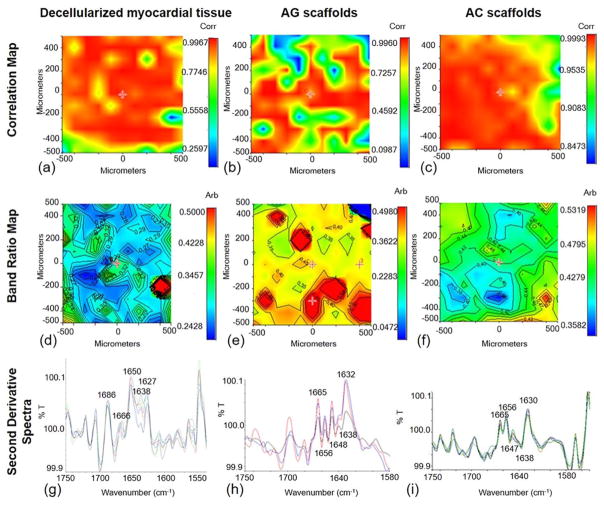

To evaluate the chemical homogeneity of AG and AC scaffolds and decellularized myocardial tissue, FT-IR chemical imaging analysis was carried out (Fig. 2). For each sample, the chemical map was acquired. From this map, the medium spectrum, which is the most representative spectrum of the chemical map, was recorded and the correlation map between the chemical map and the medium spectrum was elaborated. The correlation maps [Figs. 2(a–c)] showed correlation values close to 1, indicating a high chemical homogeneity of both natural tissue and sponges.

FIGURE 2.

FT-IR chemical imaging analyses. Correlation maps of (a) decellularized myocardial tissue, (b) AG scaffold, and (c) AC scaffold; maps in function of the band ratio between polysaccharide and Amide I absorption peaks, for (d) decellularized myocardial tissue, (e) AG scaffold, and (f) AC scaffold; second derivative spectra of (g) decellularized myocardial tissue, (h) AG scaffold, and (i) AC scaffold. Note that the scale bars in panels (a–c) and those in (d–f) are different because they are the result of calculations made by the instrument software (respectively, correlation and band ratio); therefore, direct comparisons of colors should not be made.

To investigate the balance between the polysaccharide and protein components, a band ratio map was elaborated for each sample. In particular, the ratio between the absorption peak due to the polysaccharide component and the Amide I absorption peak of the protein material was calculated [Fig. 2(d–f)]. The obtained value for the native tissue [Fig. 2(d)] was in the range 0.23–0.32. A value lower than 1 was expected, being the native cardiac ECM mainly composed by proteins. Similarly, for AG sponges the ratio between polysaccharide and Amide I absorption peaks was around 0.35 [Fig. 2(e)]. A few regions presented higher values of this ratio (up to 0.45), indicating the presence of alginate clusters. In the case of AC scaffolds, the values of polysaccharide/Amide I band ratio, between 0.40 and 0.49, were slightly higher than those of AG scaffolds and the native tissue [Fig. 2(f)]. This may be attributed to the lower flexibility of collagen, which reduces the interactions with alginate, thus inducing a higher polysaccharide surface deposition.

Second derivative maps of the samples were also acquired to investigate protein secondary structure [Figs. 2(g–i)]. It is well known that the deconvolution of Amide I band is relevant for the identification of polypeptide conformation.40 Spectra collected from the second derivative map of the native tissue [Fig. 2(g)] showed the presence of typical peaks, which pointed out the secondary structure of collagen proteins in natural cardiac ECM. The secondary structure was characterized by β-turn (1666 and 1627 cm−1), α-helix (1650 cm−1), and triple helix (1638 cm−1) structures. The Amide I deconvolution of AG sponge [Fig. 2(h)] showed the presence of bands due to β-turn conformation (1665 and 1632 cm−1), α-helix (1656 cm−1), disordered forms (1648 cm−1), and triple helix (1638 cm−1). The presence of the α-helix and triple helix typical peaks was particularly significant. It is possible that the interactions between the two polymeric components of AG sponges produced a partial reorganization of the gelatin secondary structure. Even though β-turn conformation and unordered forms were much more evident in the scaffold than in the native tissue, the two samples were very similar in terms of α-helix and triple helix contents. In the case of AC sponges, Amide I deconvolution [Fig. 2(i)] showed the bands due to β-turn conformation, α-helix, and disordered forms. When compared with the AG scaffolds, the α-helix band in the AC scaffolds was much more evident due to disordered forms.

Swelling test

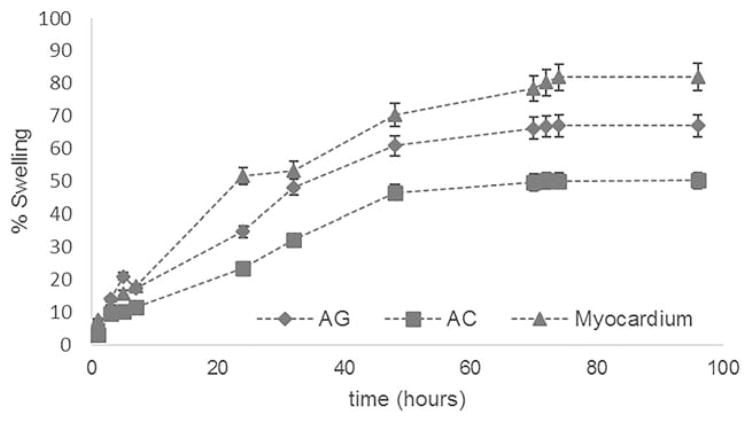

The water sorption capacity of the developed scaffolds and native tissue was determined by swelling test, as a measure of sample hydrophilicity. It is well known that substrate hydrophilicity influences cell adhesion.41 Moreover, when a scaffold is capable of swelling, its pores increase in diameter, thus promoting cell migration inside the scaffold during in vitro cell culture. Therefore, tissue-engineering scaffolds should ideally mimic the hydrophilicity of the native ECM, for a proper cell colonization. The swelling kinetics are reported for the AG and AC scaffolds, as well as for the native myocardium, in Figure 3. High values of water uptake were obtained. The equilibrium swelling value was reached after 72 h. The natural tissue showed a higher swelling percentage (swelling plateau at around 80%) than the scaffolds. The AG sponges were more hydrophilic (swelling plateau at around 70%) than the AC ones (swelling plateau at around 50%). The latter result was expected, since gelatin is a denatured form of collagen, more hydrophilic than pristine collagen.

FIGURE 3.

Swelling kinetics of AG and AC scaffolds, compared with native myocardial tissue.

In vitro degradation

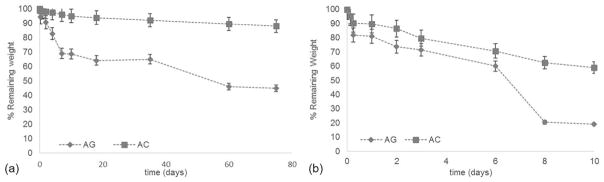

Alginate, collagen, and gelatin used in scaffold preparation are all biodegradable materials. However, both polymer blending and crosslinking treatments may have an impact on the degradation behavior. Therefore, degradation tests of the scaffolds were performed in vitro. Samples were maintained in PBS for 75 days for the hydrophilic degradation test and in a collagenase solution for 10 days for the enzymatic degradation test.

The hydrolytic degradation test [Fig. 4(a)] showed that the ionic and chemical crosslinking provides the sponges with a suitable stability in an aqueous environment. After 75 days of hydrolysis, the percentages of remaining weight were 88% for AC scaffolds and 45% for AG scaffolds. These results were in agreement with the swelling test: the more hydrophilic sample (AG) underwent a more rapid hydrolytic degradation, with a lower value of percentage remaining weight at the end of the test.

FIGURE 4.

(a) Hydrolytic degradation of the AG and AC scaffolds. (b) Enzymatic degradation of the AG and AC scaffolds.

The enzymatic degradation test showed that both scaffold types underwent a higher and more rapid weight loss compared with hydrolytic degradation when collagenase was added to PBS [Fig. 4(b)]. Comparing the results obtained in the two different tests, after the same time interval (10 days), the percentages of remaining weight during enzymatic degradation were 59% for AC scaffolds and 19% for AG scaffolds, while in the case of hydrolytic degradation they were 95% for AC scaffolds and 69% for AG scaffolds. The faster degradation of AG scaffolds could be attributed to the smaller molecular weights of gelatin molecules than collagen, consistent with the observed swelling behavior (Fig. 3). These results demonstrated that the chemical crosslinking, performed to provide a suitable stability to the scaffolds, did not prevent the degradation of the protein component in an aqueous environment.

Mechanical characterization

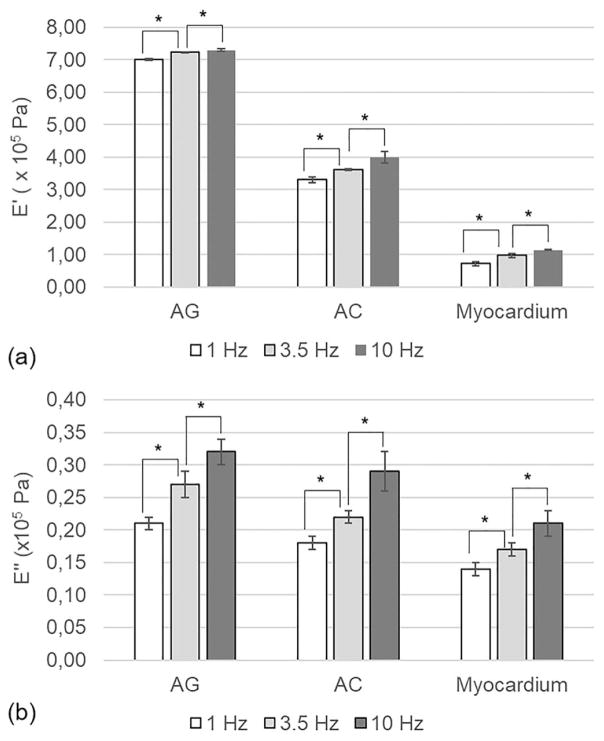

Adequate mechanical behavior of the scaffold is one of the main challenges in CTE.42 Mechanical tests were carried out on our scaffolds and on the native tissue, to determine their storage modulus (E′) and loss modulus (E″). The results are shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

(a) Storage (E′) and (b) loss (E″) modulus of AG sponges, AC sponges and decellularized myocardial tissue, measured by DMA at three different frequencies (1, 3.5, and 10 Hz). The data (n = 5; error bars= ± SD) were compared using Student’s t test and differences were considered significant when *p <0.05.

For all the analyzed samples, increasing the oscillation frequency resulted in increases of both E′ and E″ values. Moreover, for both the myocardium and the prepared scaffolds, the values of loss modulus were significantly lower than those of the storage modulus, indicating a predominant elastic behavior. These results were in agreement with the recent report discussing the viscoelastic properties of the myocardial tissue.43

Comparing the viscoelastic properties of the developed scaffolds with those of the decellularized myocardium, lower storage and loss modulus were observed for the native tissue. In addition, values of E′ and E″ were higher for the AG sponges than those for the AC ones. This result may be explained by the interactions between the protein and polysaccharide components in the AG sponges, as revealed by our FT-IR characterization. A CTE scaffold stiffer than the native myocardium may offer several advantages, including a reduction of infarct expansion, attenuation of left ventricle remodeling, and amelioration of global left ventricle function.44,45 Therefore, our mechanical characterization results suggested that both scaffolds developed in this work, and particularly the AG sponges, may improve the outcome of a CTE procedure by decreasing heart wall stress.46

Cellular responses

A preliminary assessment of cell behavior on the scaffolds developed in this work was performed to select the most bioactive type of scaffolds for subsequent dynamic analysis in microfluidic bioreactors. In vitro proliferation and differentiation tests were performed using C2C12 myoblasts, as a model of a possible cell source for myocardial regeneration. The C2C12 is a subclone from myoblast line established from normal adult C3H mouse leg muscle. Skeletal myoblasts have been explored as an alternative cell source to cardiomyocytes for cardiac repair.47,48 Skeletal myoblasts can offer advantages with respect to other cell sources: (1) autologous myoblasts can be easily obtained from patient muscle biopsies, thus requiring no immunosuppression; (2) as such, the donor availability issue is minimal; (3) the risk for malignant transformation is absent; and (4) skeletal muscle is much more resistant to ischemia than cardiac muscle.47,48 The efficacy of skeletal myoblasts for myocardial repair was demonstrated by clinically relevant studies in both small and large animal models,49–52 as well as by human clinical trials,53–55 thus justifying their choice in this study.

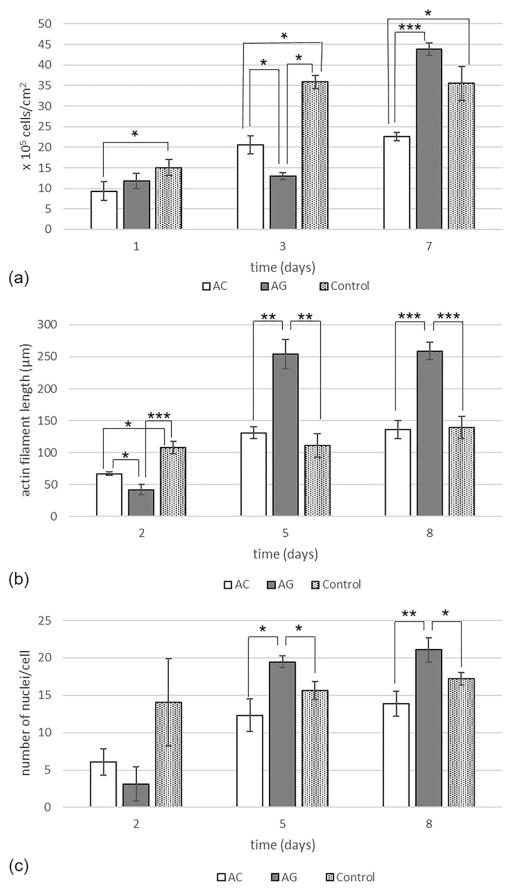

Results of C2C12 proliferation and differentiation assessments are shown in Figure 6. With regard to the cell proliferation assay [Fig. 6(a)], it was observed that, 7 days after seeding the level of cell proliferation on AG sponges was comparable to the positive control and significantly higher (p <0.001) than that observed on AC scaffolds.

FIGURE 6.

(a) Myoblast proliferation on the AC and AG sponges. (b) Myoblast differentiation (measured by actin filament length evaluation) on the AC and AG sponges. (c) Myoblast differentiation (measured by number of nuclei per cell evaluation) on AC and AG sponges. The data (n = 8; error bars = ± SD) were compared using Student’s t test and differences were considered significant when *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001.

Cell differentiation was also analyzed. As reported in literature, during C2C12 myoblast differentiation, the formation of multinucleated elongated myotubes is observed, reaching up to >20 nuclei per cell and a length of 100–600 μm.56 In this work, cell differentiation was evaluated by measuring two parameters, actin filament length and number of nuclei per cell.29,38 Starting from day 5 after seeding, both parameters were significantly higher on the AG sponges than on the AC sponges and on positive control [Fig. 6(b,c)].

Overall, the results of the morphological, physicochemical, functional, and cellular assessments carried out on the AC and AG sponges suggested a superior behavior of the AG scaffolds. A possible explanation for such observation is the stronger molecular interactions established between gelatin molecules and the polysaccharide component. Although collagen is a structural protein, gelatin has much smaller average molecular weight and is thus more flexible to interact with alginate. These improved inter-molecular interactions may subsequently influence the structural conformation of molecules in the AG samples. Indeed, as shown by the FT-IR analysis of the protein secondary structures, a conformational change of gelatin from random coil to an ordered structure occurred in the AG scaffolds. In particular, the conformation acquired by gelatin when blended with alginate is similar to that of non-fibrillar collagens.57 As reported in literature, non-fibrillar collagens play a key role during tissue development.58,59 Therefore, the reorganization of gelatin to a non-fibrillar collagen-like structure could explain the superior behavior of AG sponges than AC ones, as scaffolds for cell growth. AG sponges were therefore selected for all further investigation.

Cardiac bioreactor evaluation

To evaluate the cellular responses to the AG scaffolds under dynamic conditions, we further designed a microfluidic bioreactor for perfusion culture of cardiomyocytes seeded onto the scaffolds. Even though, as explained in the previous section, numerous studies have reported improvements in cardiac function using skeletal myoblasts, cardiomyocytes remain the ideal cell source for cardiac regeneration, thanks to their electrophysiological and contractile properties.46 Therefore, cell culture tests within the microfluidic bioreactor on the selected AG sponges were performed using neonatal rat cardiomyocytes.

As shown in Figure 7(a), a cardiac bioreactor was designed according to our recently published protocol.34 The bioreactor was composed of two pieces of PDMS elastomer containing opposing cavities, which when placed together will form a hollow chamber in the center with an inlet from the bottom left while outlet from the top right. The resealable design was adopted for convenient immobilization of the scaffold in the chamber. In addition, the fact that the inlet is at the lower layer of the fluidics and outlet at the higher layer resulted in easy effluence of gas bubbles generated inside the circulation, potentially minimizing the interference with optical imaging of the scaffold through the transparent window underneath.34 Two PMMA boards were then cut and used to clamp the PDMS microfluidic bioreactor in the middle via screw/bolt pairs to prevent any fluidic leakage during perfusion. In addition, a miniature fixation unit was fabricated from a PMMA ring fitted with four metal legs [Fig. 7(b)], such that it could be inserted into the PDMS bottom of the chamber to immobilize the scaffold in between, rendering it unaffected by the fluidic flow. An actual device hosting an AG scaffold is shown in Figure 7(c). It is clear that the scaffold could be tightly fixed in the center of the bioreactor chamber to allow for perfusion culture of the cells seeded inside [Fig. 7(d)].

FIGURE 7.

(a) Schematic diagram showing the design of the microfluidic cardiac bioreactor. (b) Schematic and photograph showing the design of the scaffolds fixation unit. (c,d) Photographs showing an assembled bioreactor and the magnified views of the chamber where the scaffold was hosted.

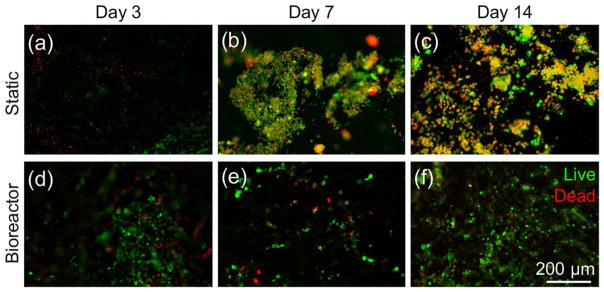

Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were seeded onto the AG scaffolds at a density of 4 × 106 per scaffold, and cultured under static conditions for 3 days. Afterwards, the cell-seeded scaffolds were divided into two groups, one transferred into the bioreactor for dynamic culture at a flow rate of 200 μL/h whereas the other group remained in static culture in the plates. The viability of the cells was evaluated for up to 14 days post seeding. Although the cells showed similar viability under both conditions at day 3 [Fig. 8(a,d)], the number of live cells significantly dropped over time during static culture where no media exchange was present, as indicated by gradually increasing ratio of overlaying staining of live and dead cells [Fig. 8(a–c)]. Under the dynamic culture however, the majority of the cardiomyocytes were able to stay alive due to significantly better nutrient transport provided by the perfusion. Interestingly, some samples in the bioreactor group showed spontaneously beating at later stages of culture.

FIGURE 8.

(a–f) Fluorescence micrographs showing the live/dead staining of the cardiomyocytes in the AG scaffolds at days 3, 7, and 14 under static and dynamic conditions, respectively.

These results demonstrated the importance of the dynamic flow exchange on the viability of cardiomyocytes cultured in the AG scaffolds, indicating that the AG scaffold could be potentially used as an enabling substrate to support CTE in combination with microfluidic bioreactors to improve the overall outcome.

CONCLUSIONS

Myocardial infarction is a progressive pathological process, characterized by cell death and ECM damage. Tissue engineering strategies try to combine cells with scaffolds, with the aim to promote myocardial infarction repair. The scaffold should temporarily replace the ECM of the native tissue, offering structural support to cells and promoting the healing process.

In the last few years, the design of scaffolds based on blends of proteins and polysaccharides, as surrogates of the native ECM, has emerged as a very promising strategy for several tissue engineering applications, including skin, cornea, peripheral nerve, cartilage and bone. In this work, we have developed and characterized a new class of 3D porous scaffolds based on polysaccharide/protein blends mimicking the natural ECM, for cardiac tissue regeneration. Sponges based on mixtures of alginate with collagen or gelatin, at 20:80 weight ratios, were produced by freeze-drying and subsequent ionic and chemical crosslinking procedures.

In native ECM, the chemical composition, as well as the degree and the type of interactions between components can influence several important properties, such as the hydrophilicity degree, as well as morphological, mechanical, and surface chemical properties. All these properties have impacts on cell responses. Therefore, we aimed to replicate within the scaffolds not only the chemical composition but also the molecular interactions, which are present in the native ECM.

Considering that the goal of this work was the development of scaffolds mimicking the native ECM and the lack of literature related with the characterization of the native myocardial tissues, a comparison was made between the produced scaffolds and the natural porcine myocardial tissue, all of which underwent the same sets of characterizations to enable direct comparison.

We proved that our scaffolds possessed highly porous and interconnected structures, and the chemical homogeneity of the native ECM was well-reproduced. Furthermore, the AG scaffolds better-mimicked the native tissue in terms of interactions between components and protein secondary structure, as well as the swelling behavior. The AG scaffolds also showed superior mechanical properties for the desired application and this could represent an advantage in reduction of infarct expansion, attenuation of left ventricle remodeling, and amelioration of global left ventricle function.

The produced scaffolds were also analyzed with in vitro cell cultures. The AG scaffolds supported better adhesion, growth, and differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts under static conditions and therefore they were subsequently used for culturing neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. High viability of the resulting cardiac constructs, under dynamic flow culture in a microfluidic bioreactor, was observed.

Our hypothesis to explain the better similarity with the native tissue and the overall superior behavior of the AG scaffolds with respect to the AC ones, is based on the stronger molecular interactions occurring between gelatin and alginate. In particular, as demonstrated by the IR analysis, these interactions could have resulted in gelatin acquiring a conformation similar to that of non-fibrillar collagens, which are known to play a key role during tissue development.

Overall, the results obtained in this work have suggested that our AG scaffolds can potentially function as a promising cardiac ECM substitute for tissue-engineering applications. Future work will concern the development of biomimetic scaffolds including a third polymeric component (elastin) and the reinforcement of the scaffolds by fiber structures to improve their suturability to facilitate further in vivo examinations.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; contract grant number: K99CA201603; Massachusetts Institute of Technology-University of Pisa Project (first call for Seed Funds, year 2013).

This work was partially supported by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology-University of Pisa Project (first call for Seed Funds, year 2013). Y.S.Z. acknowledges the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K99CA201603). E.R. and M.G.C. also would like to acknowledge Prof. Francesco D’Errico for his contribution to the final revision of the article.

References

- 1.Kelly D, Khan S, Cockerill G, Ng LL, Thompson M, Samani NJ, Squire IB. Circulating stromelysin-1 (MMP-3): a novel predictor of LV dysfunction, remodelling, and all-cause mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann DL. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: a combinatorial approach. Circulation. 1999;100:999–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby P, Lee RT. Matrix matters. Circulation. 2000;102:1874–1876. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.16.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czyz J, Wobus AM. Embryonic stem cell differentiation: the role of extracellular factors. Differentiation. 2001;68:167–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.680404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corda S, Samuel JL, Rappaport L. Extracellular matrix and growth factors during heart growth. Heart Fail Rev. 2000;5:119–130. doi: 10.1023/A:1009806403194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ju H, Dixon IM. Extracellular matrix and cardiovascular diseases. Can J Cardiol. 1996;12:1259–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson DG, Terracio L, Terracio M, Price RL, Turner DC, Borg TK. Modulation of cardiac myocyte phenotype in vitro by the composition and orientation of the extracellular matrix. J Cell Physiol. 1994;161:89–105. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041610112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akhyari P, Fedak PW, Weisel RD, Lee TY, Verma S, Mickle DA, Li RK. Mechanical stretch regimen enhances the formation of bioengineered autologous cardiac muscle grafts. Circulation. 2002;106:I137–I142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eschenhagen T, Didie M, Munzel F, Schubert P, Schneiderbanger K, Zimmermann W-H. 3D engineered heart tissue for replacement therapy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2002;97:I146–I152. doi: 10.1007/s003950200043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dar A, Shachar M, Leor J, Cohen S. Optimization of cardiac cell seeding and distribution in 3D porous alginate scaffolds. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2002;80:305–312. doi: 10.1002/bit.10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christman KL, Fok HH, Sievers RE, Fang Q, Lee RJ. Fibrin glue alone and skeletal myoblasts in a fibrin scaffold preserve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:403–409. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro L, Cohen S. Novel alginate sponges for cell culture and transplantation. Biomaterials. 1997;18:583–590. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(96)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saarai A, Kasparkova V, Sedlacek T, Saha P. On the development and characterisation of crosslinked sodium alginate/gelatine hydrogels. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2013;18:152–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tonsomboon K, Oyen ML. Composite electrospun gelatin fiber-alginate gel scaffolds for mechanically robust tissue engineered cornea. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2013;21:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harley BA, Spilker MH, Wu JW, Asano K, Hsu HP, Spector M, Yannas IV. Optimal degradation rate for collagen chambers used for regeneration of peripheral nerves over long gaps. Cells Tissues Organs. 2004;176:153–165. doi: 10.1159/000075035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Li K, Xiao W, Zheng L, Xiao Y, Fan H, Zhang X. Preparation of collagen–chondroitin sulfate–hyaluronic acid hybrid hydrogel scaffolds and cell compatibility in vitro. Carbohyd Polym. 2011;84:118–125. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balakrishnan B, Joshi N, Jayakrishnan A, Banerjee R. Self-cross-linked oxidized alginate/gelatin hydrogel as injectable, adhesive biomimetic scaffolds for cartilage regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:3650–3663. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Smith LA, Hu J, Ma PX. Biomimetic nanofibrous gelatin/apatite composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2252–2258. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barbani N, Guerra GD, Cristallini C, Urciuoli P, Avvisati R, Sala A, Rosellini E. Hydroxyapatite/gelatin/gellan sponges as nanocomposite scaffolds for bone reconstruction. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2012;23:51–61. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen ZG, Wang PW, Wei B, Mo XM, Cui FZ. Electrospun collagen–chitosan nanofiber: A biomimetic extracellular matrix for endothelial cell and smooth muscle cell. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:372–382. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sang L, Luo D, Xu S, Wang X, Li X. Fabrication and evaluation of biomimetic scaffolds by using collagen–alginate fibrillar gels for potential tissue engineering applications. Mat Sci Eng C. 2011;31:262–271. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarker B, Papageorgiou DG, Silva R, Zehnder T, Gul-E-Noor F, Bertmer M, Kaschta J, Chrissafis K, Detsch R, Boccaccini AR. Fabrication of alginate–gelatin crosslinked hydrogel microcapsules and evaluation of the microstructure and physico-chemical properties. J Mater Chem B. 2014;2:1470–1482. doi: 10.1039/c3tb21509a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engelmayr GC, Cheng M, Bettinger CJ, Borenstein JT, Langer R, Freed LE. Accordion-like honeycombs for tissue engineering of cardiac anisotropy. Nat Mater. 2008;7:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/nmat2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosellini E, Vozzi G, Barbani N, Giusti P, Cristallini C. Three-dimensional microfabricated scaffolds with cardiac extracellular matrix-like architecture. Int J Artif Organs. 2010;33:885–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kharaziha M, Nikkhah M, Shin S, Annabi N, Masoumi N, Gaharwar AK, Camci-Unal G, Khademhosseini A. PGS:Gelatin nanofibrous scaffolds with tunable mechanical and structural properties for engineering cardiac tissues. Biomaterials. 2013;34:6355–6366. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai XP, Zheng HX, Fang R, Wang TR, Hou XL, Li Y, Chen XB, Tian WM. Fabrication of engineered heart tissue grafts from alginate/collagen barium composite microbeads. Biomed Mater. 2011;6:045002–0410. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/6/4/045002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonnerman EA, Kelkhoff DO, McGregor LM, Harley BAC. The promotion of HL-1 cardiomyocyte beating using anisotropic collagen-GAG scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8812–8821. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bai X, Fang R, Zhang S, Shi X, Wang Z, Chen X, Yang J, Hou X, Nie Y, Li Y, Tian W. Self-cross-linkable hydrogels composed of partially oxidized alginate and gelatin for myocardial infarction repair. J Bioact Compat Pol. 2013;28:126–140. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosellini E, Cristallini C, Barbani N, Vozzi G, Giusti P. Preparation and characterization of alginate/gelatin blend films for cardiac tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;91:447–453. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramires PA, Milella E. Biocompatibility of poly(vinyl alcohol)-hyaluronic acid and poly(vinyl alcohol)-gellan membranes crosslinked by glutaraldehyde vapors. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2002;13:119–123. doi: 10.1023/a:1013667426066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saravanan S, Nethala S, Pattnaik S, Tripathi A, Moorthi A, Selvamurugan N. Preparation, characterization and antimicrobial activity of a bio-composite scaffold containing chitosan/nano-hydroxyapatite/nano-silver for bone tissue engineering. Int J Bio Macromol. 2011;49:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daniliuc L, De Kesel C, David C. Intermolecular interactions in blends of poly(vinyl alcohol) with poly(acrylic acid)-1. FTIR and DSC studies Eur Polym J. 1992;28:1365–1371. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khademhosseini A, Eng G, Yeh J, Kucharczyk P, Langer R, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Radisic M. Microfluidic patterning for fabrication of contractile cardiac organoids. Biomedical Microdevices. 2007;9:149–157. doi: 10.1007/s10544-006-9013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhise N, Manoharan V, Massa S, Tamayol A, Ghaderi M, Miscuglio M, Lang Q, Zhang YS, Shin SR, Calzonne G, Annabi N, Shupe T, Bishop C, Atala A, Dokmeci M, Khademhosseini A. A liver-on-a-chip platform with bioimprinted hepatic spheroids. Biofabrication. 2016;8:014101. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/8/1/014101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruder SP, Caplan AI. Bone regeneration through cellular engineering. In: Lanza RP, Langer R, Vacanti JP, editors. Principles of Tissue Engineering. California: Academic Press; 2000. p. 683696. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hileman RE, Fromm JR, Weiler JM, Linhardt RJ. Glycosaminoglycan-protein interactions: definition of consensus sites in glycosaminoglycan binding proteins. BioEssays. 1998;20:156–167. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199802)20:2<156::AID-BIES8>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens MM, George JH. Exploring and engineering the cell surface interface. Science. 2005;310:1135–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.1106587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosellini E, Cristallini C, Barbani N, Vozzi G, D’Acunto M, Ciardelli G, Giusti P. New bioartificial systems and biodegradable synthetic polymers for cardiac tissue engineering: a preliminary screening. Biomed Eng-App Bas C. 2010;22:497–507. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong Z, Wang Q, Du Y. Alginate/gelatin blend films and their properties for drug controlled release. J Membrane Sci. 2006;280:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segtnan VH, Isaksson T. Temperature, sample and time dependant structural characteristics of gelatin gels studied by near infrared spectroscopy. Food Hydrocoll. 2004;18:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horbett TA, Waldburger JJ, Ratner BD, Hoffman AS. Cell adhesion to a series of hydrophilic-hydrophobic copolymers studied with a spinning disc apparatus. J Biomed Mater Res. 1988;22:383–404. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820220503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen QZ, Harding SE, Ali NN, Lyon AR, Boccaccini AR. Biomaterials in cardiac tissue engineering: Ten years of research survey. Mater Sci Eng R. 2008;59:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramadan S, Paul N, Naguib HE. Standardized static and dynamic evaluation of myocardial tissue properties. Biomed Mater. 2017;12:025013. doi: 10.1088/1748-605X/aa57a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wall ST, Walker JC, Healy KE, Ratcliffe MB, Guccione JM. Theoretical impact of the injection of material into the myocardium: a finite element model simulation. Circulation. 2006;114:2627–2635. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.657270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wenk JF, Eslami P, Zhang Z, Xu C, Kuhl E, Gorman JH, Robb JD, Ratcliffe MB, Gorman RC, Guccione JM. A novel method for quantifying the in-vivo mechanical effect of material injected into a myocardial infarction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morita M, Eckert CE, Matsuzaki K, Noma M, Ryan LP, Burdick JA, Jackson BM, Gorman JH, Sacks MS, Gorman RC. Modification of infarct material properties limits adverse ventricular remodeling. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siminiak T, Kurpisz M. Myocardial Replacement Therapy. Circulation. 2003;108:1167–1171. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086628.42652.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leor J, Amsalem Y, Cohen S. Cells, scaffolds, and molecules for myocardial tissue engineering. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105:151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dorfman J, Duong M, Zibaitis A, Pelletier MP, Shum-Tim D, Li C, Chiu RCJ. Myocardial tissue engineering with autologous myoblast implantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:744–751. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)00451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor DA, Atkins BZ, Hungspreugs P, Jones TR, Reedy MC, Hutcheson KA, Glower DD, Kraus WE. Regenerating functional myocardium: improved performance after skeletal myoblast transplantation. Nat Med. 1998;4:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson SW, Cho PW, Levitsky HI, Olson JL, Hruban RH, Acker MA, Kessler PD. Arterial delivery of genetically labelled skeletal myoblasts to the murine heart: long-term survival and phenotypic modification of implanted myoblasts. Cell Transplant. 1996;5:77–91. doi: 10.1177/096368979600500113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyagawa S, Saito A, Sakaguchi T, Yoshikawa Y, Yamauchi T, Imanishi Y, Kawaguchi N, Teramoto N, Matsuura N, Iida H, Shimizu T, Okano T, Sawa Y. Impaired myocardium regeneration with skeletal cell sheets - a preclinical trial for tissue-engineered regeneration therapy. Transplantation. 2010;90:364–372. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e6f201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menasche P, Hagege AA, Vilquin JT, Desnos M, Abergel E, Pouzet B, Bel A, Sarateanu S, Scorsin M, Schwartz K, Bruneval P, Benbunan M, Marolleau JP, Duboc D. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for severe post-infarction left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1078–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hagege AA, Marolleau JP, Vilquin JT, Alheritiere A, Peyrard S, Duboc D, Abergel E, Messas E, Mousseaux E, Schwartz K, Desnos M, Menasche P. Skeletal myoblast transplantation in ischemic heart failure long-term follow-up of the first phase i cohort of patients. Circulation. 2006;114:I-108–I-113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawa Y, Miyagawa S, Sakaguchi T, Fujita T, Matsuyama A, Saito A, Shimizu T, Okano T. Tissue engineered myoblast sheets improved cardiac function sufficiently to discontinue lvas in a patient with dcm: report of a case. Surg Today. 2012;42:181–184. doi: 10.1007/s00595-011-0106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burattini S, Ferri P, Battistelli M, Curci R, Luchetti F, Falcieri E. C2C12 murine myoblasts as a model of skeletal muscle development: morpho-functional characterization. Eur J Histochem. 2004;48:223–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petibois C, Gouspillou G, Wehbe K, Delage JP, Deleris G. Analysis of type I and IV collagens by FT-IR spectroscopy and imaging for a molecular investigation of skeletal muscle connective tissue. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;386:1961–1966. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gelse K, Poschl E, Aigner T. Collagens-structure, function, and biosynthesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:1531–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shamhart PE, Meszaros JG. Non-fibrillar collagens: key mediators of postinfarction cardiac remodeling? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]