Abstract

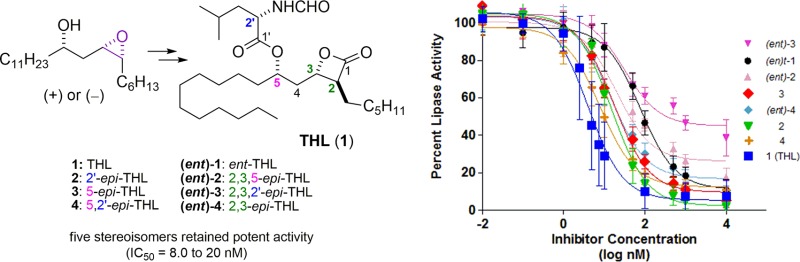

Tetrahydrolipstatin (THL), its enantiomer, and an additional six diastereomers were evaluated as inhibitors of the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl butyrate by porcine pancreatic lipase. IC50s were found for all eight stereoisomers ranging from a low of 4.0 nM for THL to a high of 930 nM for the diastereomer with the inverted stereocenters at the 2,3,2′-positions. While the enantiomer of THL was also significantly less active (77 nM) the remaining five stereoisomers retained significant inhibitory activities (IC50s = 8.0 to 20 nM). All eight compounds were also evaluated against three human cancer cell lines (human breast cancers MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, human large-cell lung carcinoma H460). No appreciable cytotoxicity was observed for THL and its seven diastereomers, as their IC50s in a MTT cytotoxicity assay were all greater than 3 orders of magnitude of camptothecin.

Keywords: tetrahydrolipstatin, pancreatic lipase, diastereomers, inhibitory activity, cytotoxicity, structure activity relationship

Tetrahydrolipstatin (THL, 1)1,2 is an FDA approved oral antiobesity drug that inhibits pancreatic lipase digestive enzyme.3−5 Inhibition of pancreatic lipase in the intestinal lumen results in the inability to digest dietary triacylglycerides (fat) and diacylglycerides to free fatty acids and monoacylglycerides that can be absorbed into the bloodstream and lymphatic system. Dietary fat and diacylglycerides are then eliminated as bodily waste without the caloric consequences of their taste and consumption. As part of an effort aimed at developing a novel treatment for pancreatitis, we became interested in structure activity space around THL (1). Pancreatitis is believed to result from the excessive release of active pancreatic digestive enzymes.6 As THL (1) is known to inhibit pancreatic lipase by covalent modification, it was identified as lead structure in our program aimed at capturing and removing excess pancreatic lipase.

THL (1) is known to be a potent inhibitor of porcine pancreatic lipase hydrolysis of triolein (fat) emulsion (IC50 of 360 nM).1 The mechanism of activity for THL (1) has been shown to occur via ring opening of the β-lactone by a lipase active site serine to form a stable ester.7−9 When the hydrolysis of the esterified serine is slow, this covalent modification of the lipase enzyme leads to essentially irreversible inactivation.

Previously, THL has been investigated in vivo for the treatment of pancreatitis by intravenous,10 intraperitoneal,11−13 and direct injection into pancreatic tissue.10−14 In addition, THL has been found to inhibit the thioesterase domain of fatty acid synthase (FAS)9,15,16 and has been investigated as anticancer chemotherapy.15−24 THL has been shown to inhibit the in vitro growth of Giardia duodenalis, a gastrointestinal parasite.25 THL may also have value as an antifungal agent against fungi that lack lipase enzymes and rely on free fatty acids for their nutrition and growth.26,27

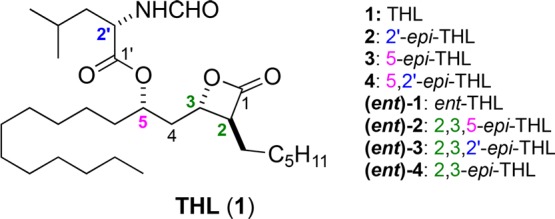

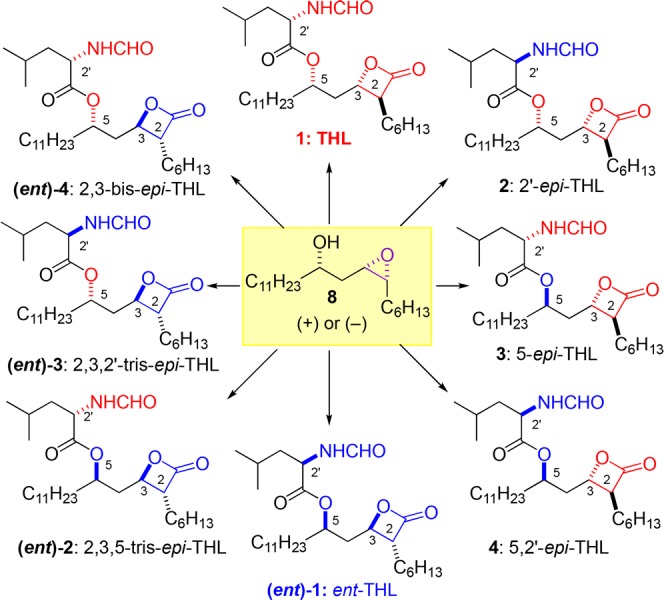

In an effort to find novel structures that covalently modified pancreatic lipase, we decided to explore the structural space around THL (1). While there had been some structure activity relationship studies (SAR) of the lipstatins, there have been fewer studies of its stereoisomers. The syntheses of some THL diastereomers have been reported (e.g., 2, 3, (ent)-2, (ent)-4, and the 3-epi-THL), along with a smattering of lipase activities (e.g., 2, 3, and the 3-epi-THL).16,23,28−30 For instance, the C2′ epimer 2, was reported to be less potent than THL (1) in a diacylglycerol lipase assay.29 Similarly, the cis-β-lactone isomer (3-epi-THL)23 has been evaluated for lipase inhibitory activity (IC50 = 15 nM). However, no systematic study of the trans-β-lactone stereoisomers has been reported. Thus, we identified seven trans-β-lactone stereoisomers of THL (2-4 and (ent)-1–4) as compounds for a convenient method to identify the structural space around the enzyme active site (Figure 1). Importantly, these types of comprehensive stereochemical-SAR studies (S-SAR) of natural products and their derivatives, require an asymmetric synthetic approach to the structure of interest.31−37

Figure 1.

Structures of THL (1) and seven diastereomers.

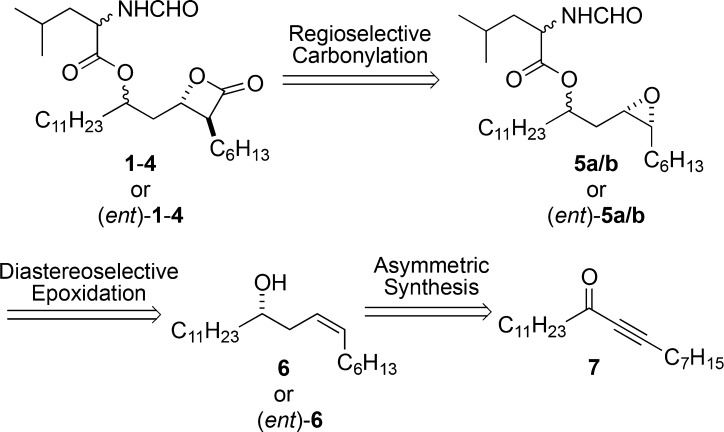

Over the years there have been numerous syntheses of THL and related molecules.38−41 Our own successful synthesis of THL was of the de novo asymmetric variety and as a result was stereodivergent in its approach. Specifically, it used a catalytic asymmetric reduction of achiral ynone 7 to install the initial stereocenter (Scheme 1), followed by a diastereoselective epoxidation of 6 and regioselective Coates carbonylation42−48 of 5 to afford either enantiomer of the four diastereomers (1–4).49 Key to the success of this stereodivergent approach was the recognition that all eight THL stereoisomers (1–4 and (ent)-1–4) could be diastereo- and regioselectively prepared from the homoallylic epoxide 8 and its enantiomer in only three steps (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1. Retrosynthetic Analysis for THL.

Scheme 2. Asymmetric Approach to THL and Seven Stereoisomers.

Herein we report the evaluation of the eight THL diastereoisomers (1–4 and (ent)-1–4). All the stereoisomers were evaluated for their lipase inhibitory properties using porcine pancreatic lipase (PPL). To ensure that the various stereochemical inversions on THL did not introduce any unwanted toxicities, the cytotoxicity of all eight stereoisomers were determined against three cancer cell lines (H460, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231).

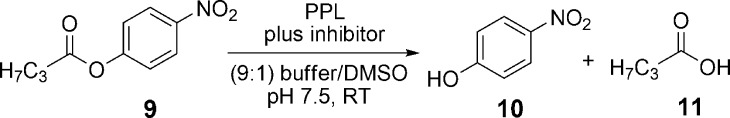

Porcine pancreatic lipase is frequently used,7,50,51 since the active site of the porcine lipase is highly homologous to the human lipase (Scheme 3).52 Porcine pancreatic lipase enzyme concentrations were varied between the range of 0.50 to 10.0 μg/200 μL in buffer solution to determine the optimal enzyme concentration of 5.0 μg/200 μL. This concentration was consistent with values used for a related assay.51 The concentration of the lipase substrate, p-nitrophenyl butyrate (p-NPB),53 in DMSO/buffer solutions were varied from 0.25 mM to 1.0 mM without any deleterious effects on IC50 values. Solubility issues became apparent at higher concentration, as such, all assays were run with a concentration of 0.25 mM p-NPB. A 10% DMSO concentration was used, which was found to be sufficient for maintaining homogeneous solutions at all assay concentrations. Using this assay, the Km (Michaelis–Menten constant) for our PPL was determined to be 2.41 mM (see Supporting Information) which corresponds well with a related assay.54

Scheme 3. Hydrolysis of p-Nitrophenyl Butyrate (pNPB) to p-Nitrophenol (pNP) by Porcine Pancreatic Lipase (PPL) in the Presence of Tetrahydrolipstatin and Its Diastereomers (1–4 and (ent)-1–4).

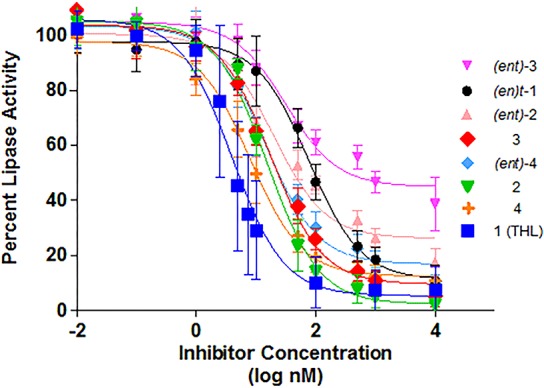

THL was found to be a very potent inhibitor of PPL with an IC50 of 4.0 nM, which correlates well with known IC50 from related assays with 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycerol as the substrate.23,29,51 None of the other seven diastereomers were more potent PPL inhibitors, with IC50 values ranging from 8.0 to 77 nM (cf, Figure 2, Table 1). One diastereomer, (ent)-3, did not show any significant inhibition of lipase activity below 100 nM, with an IC50 > 900. The error bars reflect 95% confidence limits for triplicate runs on three separate occasions (N = 9) and are consistent with slight variations in pH, enzyme concentration, and timing the start of the assays.

Figure 2.

IC50 curves for THL and seven stereoisomers against pancreatic lipase using inhibitor concentrations between 0.01 nM and 10 μM.

Table 1. IC50 of THL Diastereomers against Pancreactic Lipasea.

| Cpd | Epimerization | IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | THL | 4.0 (±1.3) |

| 2 | 2′-epi-THL | 15.4 (±2.6) |

| 3 | 5-epi-THL | 17.4 (±3.1) |

| 4 | 5,2′-epi-THL | 8.0 (±1.5) |

| (ent)-1 | ent-THL | 76.9 (±17.6) |

| (ent)-2 | 2,3,5-epi-THL | 20.0 (±7.2) |

| (ent)-3 | 2,3,2′-epi-THL | 930 (±340) |

| (ent)-4 | 2,3-epi-THL | 14.7 (±2.9) |

The results are an average of three independent triplicate experiments (N = 9). The 95% confidence limits are indicated in parentheses.

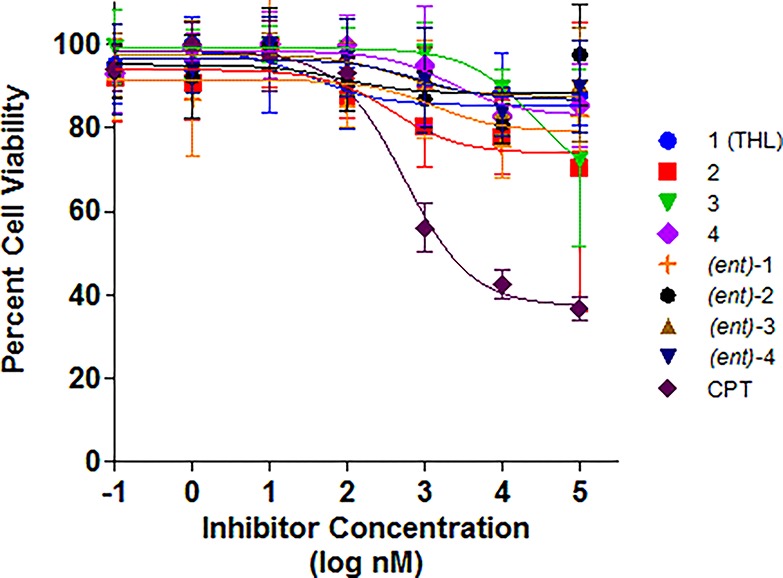

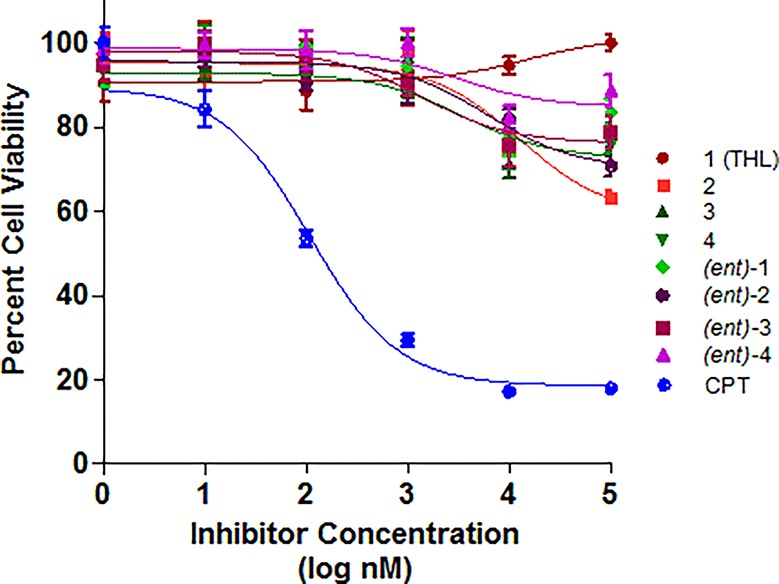

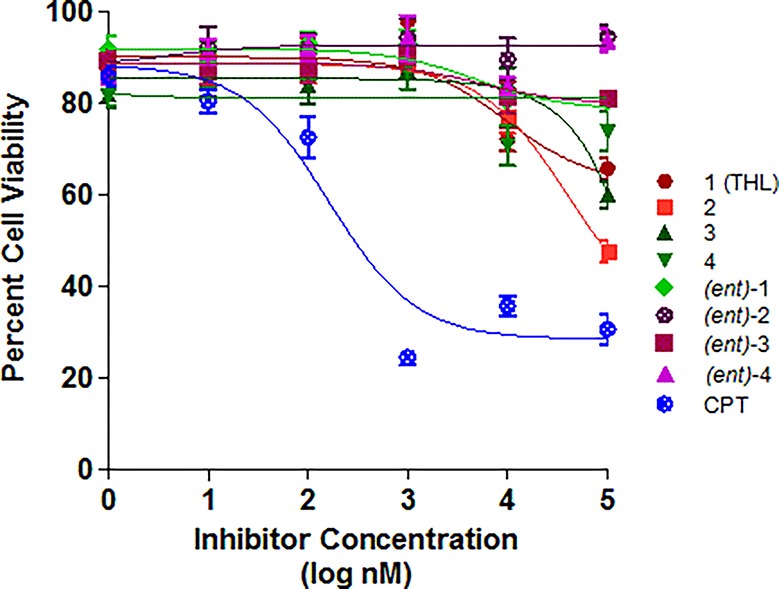

The eight stereoisomers were assayed for cytotoxicity against three human cancer cell lines: two human breast adenocarcinoma cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 and one human large-cell lung carcinoma cell line H460 (Table 2 and Figures 3–5). A standard 3-(4,5-dimethylthylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay of cell viability was used.55,56 The MDA-MB-231 was chosen as it has been previously used in several studies of THL cytotoxicities.16,23

Table 2. IC50 of THL Diastereomers against Cancer Cells (nM)a.

| compound | H460 | MDA-MB-231 | MCF-7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to (ent)-4 | >105 | >105 | >105 |

| camptothecin | 110 | 540 | 160 |

The cell line was grown in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cell/well for 12 to 16 h. IC50 values were determined via MTT assay from a 72 h drug treatment (0.1 nM to 100 μM), with untreated wells as controls. The viability was measured by UV absorbance at 570 nm. The dose-dependent experiment was performed in 2 replicate wells of each compound for a single concentration with three independent experiments (N = 6).

Figure 3.

IC50 curves for THL and seven stereoisomers against MDA-MB-231 cell line using inhibitor concentration from 0.1 nM to 100 μM. CPT = camptothecin.

Figure 5.

IC50 curves for THL and seven stereoisomers against H460 cell line using inhibitor concentration from 0.1 nM to 100 μM. CPT = camptothecin.

Of the three cell lines we tested, MDA-MB-231 was most sensitive to THL compounds. The IC50 value we observed for THL against the MDA-MB-231 was ∼100 μM, which was significantly higher than previously reported (IC50 13 μM).23 This difference may be due to variations in the culture method and assay.57−59 For the MCF-7 cell line, the IC50’s of all of the THL diastereomers were at or above 100 μM, with the lowest being for THL 2 (see Figure 4). In general, varying the stereochemistry of THL had little effect on the cytotoxicity. Interestingly, (ent)-3, the least potent PPL inhibitor, demonstrated no significant difference in cytotoxicity across the three cell lines.

Figure 4.

IC50 curves for THL and seven stereoisomers against MCF-7 cell line using inhibitor concentration from 0.1 nM to 100 μM. CPT = camptothecin.

In conclusion, synthetic THL and seven of its stereoisomers were evaluated in vitro as porcine pancreatic lipase inhibitors. This study found that the stereochemistry of THL plays a modulating role on inhibitory activity, with the IC50’s of THL and its diastereomers ranging from 4.0 to 930 nM. While THL proved to be the most potent inhibitor (4.0 nM), in this assay, several diastereomers retained significant inhibitory activity. Of these, diastereomers, (ent)-2 had the most surprising PPL-inhibitory activity (20 nM), as it is enantiomeric at the key β-lactone portion of the molecule. For comparison, the enantiomer of THL, (ent)-1, was much less active (77 nM). Interestingly, this systematic inversion of stereochemistry around the THL structure had no deleterious effects on the cytotoxicities of these molecules. These S-SAR findings suggest that there is potential for future medicinal chemistry around the β-lactone structural motif of THL. Our efforts along these lines will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Michael Mulzer and Brandon J. Tiegs for help with the Coates carbonylation. This work was supported by the NSF (Grant CHE-1565788 to G.A.O.)

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00050.

Experimental details for synthetic procedure and compound characterization (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ Co-first authors, the order is alphabetical.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hadvary P.; Hochuli E.; Kupfer E.; Lengsfeld H.; Weibel E. K.. Leucine derivatives. U.S. Patent 4,598,089, 1986.

- Hochuli E.; Kupfer E.; Maurer R.; Meister W.; Mercadal Y.; Schmidt K. Lipstatin, an inhibitor of pancreatic lipase, produced by Streptomyces toxytricini. II. Chemistry and structure elucidation. J. Antibiot. 1987, 40, 1086–1091. 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenway F. Obesity medications and the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 1999, 1, 277–287. 10.1089/152091599317198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippatos T. D.; Derdemezis C. S.; Gazi I. F.; Nakou E. S.; Mikhailidis D. P.; Elisaf M. S. Orlistat-associated adverse effects and drug interactions: a critical review. Drug Saf. 2008, 31, 53–65. 10.2165/00002018-200831010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M.; Lane P.; Lee K.; Parks D. An integrated analysis of liver safety data from orlistat clinical trials. Obes. Facts 2012, 5, 485–494. 10.1159/000341589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya C.; Navina S.; Singh V. P. Role of pancreatic fat in the outcomes of pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2014, 14, 403–408. 10.1016/j.pan.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadvary P.; Lengsfeld H.; Wolfer H. Inhibition of pancreatic lipase in vitro by the covalent inhibitor tetrahydrolipstatin. Biochem. J. 1988, 256, 357–361. 10.1042/bj2560357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadvary P.; Sidler W.; Meister W.; Vetter W.; Wolfer H. The lipase inhibitor tetrahydrolipstatin binds covalently to the putative active site serine of pancreatic lipase. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 2021–2027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemble C. W. I.; Johnson L. C.; Kridel S. J.; Lowther W. T. Crystal structure of the thioesterase domain of human fatty acid synthase inhibited by Orlistat. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 704–709. 10.1038/nsmb1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura W.; Meyer F.; Hess D.; Kirchner T.; Fischbach W.; Mossner J. Comparison of different treatment modalities in experimental pancreatitis in rats. Gastroenterol. 1992, 103, 1916–1924. 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91452-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paye F.; Presset O.; Chariot J.; Molas G.; Roze C. Role of nonesterified fatty acids in necrotizing pancreatitis: an in vivo experimental study in rats. Pancreas 2001, 23, 341–348. 10.1097/00006676-200111000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navina S.; Acharya C.; DeLany J. P.; Orlichenko L. S.; Baty C. J.; Shiva S. S.; Durgampudi C.; Karlsson J. M.; Lee K.; Bae K. T.; Furlan A.; Behari J.; Liu S.; McHale T.; Nichols L.; Papachristou G. I.; Yadav D.; Singh V. P. Lipotoxicity causes multisystem organ failure and exacerbates acute pancreatitis in obesity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 107ra110. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel K.; Trivedi R. N.; Durgampudi C.; Noel P.; Cline R. A.; DeLany J. P.; Navina S.; Singh V. P. Lipolysis of visceral adipocyte triglyceride by pancreatic lipases converts mild acute pancreatitis to severe pancreatitis independent of necrosis and inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 808–819. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgampudi C.; Noel P.; Patel K.; Cline R.; Trivedi R. N.; DeLany J. P.; Yadav D.; Papachristou G. I.; Lee K.; Acharya C.; Jaligama D.; Navina S.; Murad F.; Singh V. P. Acute lipotoxicity regulates severity of biliary acute pancreatitis without affecting its initiation. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 1773–1784. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kridel S. J.; Axelrod F.; Rozenkrantz N.; Smith J. W. Orlistat is a novel inhibitor of fatty acid synthase with antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 2070–2075. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson R. D.; Ma G.; Oyola Y.; Zancanella M.; Knowles L. M.; Cieplak P.; Romo D.; Smith J. W. Synthesis of novel β-lactone inhibitors of fatty acid synthase. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 5285–5296. 10.1021/jm800321h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez J. A.; Vellon L.; Lupu R. Antitumoral actions of the anti-obesity drug orlistat (XenicalTM) in breast cancer cells: blockade of cell cycle progression, promotion of apoptotic cell death and PEA3-mediated transcriptional repression of Her2/neu (erb B-2) oncogene. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 1253–1267. 10.1093/annonc/mdi239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little J. L.; Wheeler F. B.; Fels D. R.; Koumenis C.; Kridel S. J. Inhibition of fatty acid synthase induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 1262–1269. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho M. A.; Zecchin K. G.; Seguin F.; Bastos D. C.; Agos tini M.; Rangel A. L.; Veiga S. S.; Raposo H. F.; Oliveira H. C.; Loda M.; Coletta R. D.; Graner E. Fatty acid synthase inhibition with Orlistat promotes apoptosis and reduces cell growth and lymph node metastasis in a mouse melanoma model. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 123, 2557–2565. 10.1002/ijc.23835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling S.; Cox J.; Cenedella R. J. Inhibition of fatty acid synthase by Orlistat accelerates gastric tumor cell apoptosis in culture and increases survival rates in gastric tumor bearing mice in vivo. Lipids 2009, 44, 489–498. 10.1007/s11745-009-3298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P.-Y.; Liu K.; Ngai M. H.; Lear M. J.; Wenk M. R.; Yao S. Q. Activity-based proteome profiling of potential cellular targets of Orlistat - an FDA-approved drug with anti-tumor activities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 656–666. 10.1021/ja907716f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin F.; Carvalho M. A.; Bastos D. C.; Agostini M.; Zecchin K. G.; Alvarez-Flores M. P.; Chudzinski-Tavassi A. M.; Coletta R. D.; Graner E. The fatty acid synthase inhibitor orlistat reduces experimental metastases and angiogenesis in B16-F10 melanomas. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 977–987. 10.1038/bjc.2012.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry S.; Aubert G.; Cresteil T.; Crich D. Synthesis and bio logical investigation of the β-thiolactone and β-lactam analogs of tetrahydrolipstatin. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 2629–2632. 10.1039/c2ob06976h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Madrid D.; Duenas-Gonzalez A. Antitumor effects of a drug combination targeting glycolysis, glutaminolysis and de novo synthesis of fatty acids. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 34, 1533–1542. 10.3892/or.2015.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn J.; Seeber F.; Kolodziej H.; Ignatius R.; Laue M.; Aebischer T.; Klotz C. High sensitivity of Giardia duodenalis to tetrahydrolipstatin (orlistat) in vitro. PLoS One 2013, 8, e71597. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Saunders C. W.; Hu P.; Grant R. A.; Boekhout T.; Kuramae E. E.; Kronstad J. W.; Deangelis Y. M.; Reeder N. L.; Johnstone K. R.; Leland M.; Fieno A. M.; Begley W. M.; Sun Y.; Lacey M. P.; Chaudhary T.; Keough T.; Chu L.; Sears R.; Yuan B.; Dawson T. L. Jr. Dandruff-associated Malassezia genomes reveal convergent and divergent virulence traits shared with plant and human fungal pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 18730–18735. 10.1073/pnas.0706756104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khedidja B.; Abderrahman L. Selection of orlistat as a potential inhibitor for lipase from Candida species. Bioinformation 2011, 7, 125–129. 10.6026/97320630007125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier P.; Schneider F. Syntheses of tetrahydrolipstatin and absolute configuration of tetrahydrolipstatin and lipstatin. Helv. Chim. Acta 1987, 70, 196–202. 10.1002/hlca.19870700124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortar G.; Bisogno T.; Ligresti A.; Morera E.; Nalli M.; Di Marzo V. Tetrahydrolipstatin analogues as modulators of endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol metabolism. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 6970–6979. 10.1021/jm800978m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier A.; Pons J.-M.; et al. An asymmetric synthesis of (−)-tetrahydrolipstatin. Synthesis 1994, 1994, 1294–1300. 10.1055/s-1994-25684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuccarese M. F.; Wang Y.; Beuning P. J.; O’Doherty G. A. Cryptocaryol Structure Activity Relationship Study of Cancer Cell Cytotoxicity and Ability to Stabilize PDCD4. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 522–526. 10.1021/ml4005039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H.; Wang H.-Y. L.; Venkatadri R.; Fu D.-X.; Forman M.; Bajaj S. O.; Li H.; O’Doherty G. A.; Arav-Boger R. Digitoxin analogs with improved anti-cytomegalovirus active ity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 395–399. 10.1021/ml400529q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds J. W.; McKenna S. B.; Sharif E. U.; Wang H.-Y. L.; Akhmedov N. G.; O’Doherty G. A. C3′/C4′-Stereochemical Effects of Digitoxigenin α-L-/α-D-Glycoside in Cancer Cytotoxicity. ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 63–69. 10.1002/cmdc.201200465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.; Mulzer M.; Shi P.; Beuning P. J.; Coates G. W.; O’Doherty G. A. De Novo Asymmetric Synthesis of Fridamycin E. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 6592–6595. 10.1021/ol203041b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. Y. L.; Xin W.; Zhou M.; Stueckle T. A.; Rojanasakul Y.; O'Doherty G. A.; et al. Stereochemical Survey of Digitoxin Monosaccharides. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 73–78. 10.1021/ml100219d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisova S. A.; Guppi S. R.; Kim H. J.; Wu B.; Penn J. H.; Liu H. W.; O’Doherty G. A. De Novo Synthesis of Glycosylated Methymycin Analogues. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5150–5153. 10.1021/ol102144g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer A. K. V.; Zhou M.; Azad N.; Elbaz H.; Wang L.; Rogalsky D. K.; Rojanasakul Y.; O’Doherty G. A.; Langenhan J. M. A Direct Comparison of the Anticancer Activities of Digitoxin MeON-Neoglycosides and O-Glycosides: Oligosaccharide Chain Length-Dependant Induction of Caspase-9-Mediated Apoptosis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 326–330. 10.1021/ml1000933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Wang Y.; O’Doherty G. A. The Asymmetric Synthesis of Tetrahydrolipstatin. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2015, 4 (10), 994–1009. 10.1002/ajoc.201500240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Fidanze S. Asymmetric Synthesis of (−)-Tetrahydrolipstatin: An anti-Aldol-Based Strategy. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2405–2407. 10.1021/ol000070a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G.; Zancanella M.; Oyola Y.; Richardson R. D.; Smith J. W.; Romo D. Total synthesis and comparative analysis of orlistat, valilactone, and a transposed orlistat derivative: Inhibitors of fatty acid synthase. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4497–4500. 10.1021/ol061651o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venukadasula P.; Chegondi K. R.; Maitra S.; Hanson P. R. A concise, phosphate-mediated approach to the total synthesis of (−)-tetrahydrolipstatin. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1556–1559. 10.1021/ol1002913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getzler Y. D. Y. L.; Mahadevan V.; Lobkovsky E. B.; Coates G. W. Synthesis of β-lactones: a highly active and selective catalyst for epoxide carbonylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 1174–1175. 10.1021/ja017434u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan V.; Getzler Y. D. Y. L.; Coates G. W. [Lewis Acid]+[Co (CO)4]– complexes: a versatile class of catalysts for carbonylative ring expansion of epoxides and aziridines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2781–2784. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt J. A. R.; Lobkovsky E. B.; Coates G. W. Chromium (III) octaethylporphyrinato tetracarbonylcobaltate: a highly active, selective, and versatile catalyst for epoxide carbonylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11426–11435. 10.1021/ja051874u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church T. L.; Getzler Y. D. Y. L.; Coates G. W. The mechanism of epoxide carbonylation by [Lewis Acid]+ [Co (CO)4] – catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 10125–10133. 10.1021/ja061503t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J. W.; Lobkovsky E. B.; Coates G. W. Practical β- lactone synthesis: epoxide carbonylation at 1 atm. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3709–3712. 10.1021/ol061292x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley J. M.; Lobkovsky E. B.; Coates G. W. Catalytic double carbonylation of epoxides to succinic anhydrides: Catalyst discovery, reaction scope, and mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 4948–4960. 10.1021/ja066901a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church T. L.; Getzler Y. D. Y. L.; Byrne C. M.; Coates G. W. Carbonylation of heterocycles by homogeneous catalysts. Chem. Commun. 2007, 657–674. 10.1039/b613476a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulzer M.; Tiegs B. J.; Wang Y.; Coates G. W.; O’Doherty G. A. Total synthesis of tetrahydrolipstatin and stereoisomers via a highly regio- and diastereoselective carbonylation of epoxyhomoallylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 10814–10820. 10.1021/ja505639u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel E. K.; Hadvary P.; Hochuli E.; Kupfer E.; Lengsfeld H. Lipstatin, an inhibitor of pancreatic lipase, produced by Streptomyces toxytricini. I. Producing organism, fermentation, isolation and biological activity. J. Antibiot. 1987, 40, 1081–1085. 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M.; Bhatt S. R.; Sikka S.; Mercier R. W.; West J. M.; Makriyannis A.; Gatley S. J.; Duclos R. I. Jr. Assay and Inhibition of Diacylglycerol Lipase Activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4585–4592. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler F. K.; D’Arcy A.; Hunziker W. Structure of human pancreatic lipase. Nature 1990, 343, 771–774. 10.1038/343771a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedicord D. L.; Flynn M. J.; Fanslau C.; Miranda M.; Hunihan L.; Robertson B. J.; Pearce B. C.; Yu X.-C.; Westphal R. S.; Blat Y. Molecular characterization and identification of surrogate substrates for diacylglycerol lipase a. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 411, 809–814. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinou M.; Theodorou L. G.; Papamichael E. M. Aspects on the catalysis of lipase from porcine pancreas (type VI-s) in aqueous media: development of ion-pairs. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2012, 55, 231–236. 10.1590/S1516-89132012000200007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.-Y. L.; Wu B.; Zhang Q.; Rojanasakul Y.; O'Doherty G. A.; et al. C5′-Alkyl Substitution Effects on Digitoxigenin R-L-Glycoside Cancer Cytotoxicity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 259–263. 10.1021/ml100291n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.-Y. L.; Rojanasakul Y.; O’Doherty G. A. Synthesis and Evaluation of the α-d-/α-l-Rhamnosyl and Amicetosyl Digitoxigenin Oligomers as Antitumor Agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 264–269. 10.1021/ml100290d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavas-Obrovac L.; Jakas A.; Marczi S.; Horvat S. The influence of cell growth media on the stability and antitumour activity of methionine enkephalin. J. Pept. Sci. 2005, 11, 506–511. 10.1002/psc.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkhah M.; Strobl J. S.; Schmelz E. M.; Agah M. Evaluation of the influence of growth medium composition on cell elasticity. J. Biomechanics 2011, 44, 762–766. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler W. B.; Kelsey W. H.; Goran N. Effects of serum and insulin on the sensitivity of the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 to estrogen and antiestrogens. Cancer Res. 1981, 41, 82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.