Abstract

Introduction

Much of the efforts to develop a vaccine against the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have focused on the design of recombinant mimics of the viral attachment glycoprotein (Env). The leading immunogens exhibit native-like antigenic properties and are being investigated for their ability to induce broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs). Understanding the relative abundance of glycans at particular glycosylation sites on these immunogens is important as most bNAbs have evolved to recognize or evade the dense coat of glycans that masks much of the protein surface. Understanding the glycan structures on candidate immunogens enables triaging between native-like conformations and immunogens lacking key structural features as steric constraints limit glycan processing. The sensitivity of the processing state of a particular glycan to its structural environment has led to the need for quantitative glycan profiling and site-specific analysis to probe the structural integrity of immunogens.

Areas covered

We review analytical methodologies for HIV immunogen evaluation and discuss how these studies have led to a greater understanding of the structural constraints that control the glycosylation state of the HIV attachment and fusion spike.

Expert commentary

Total composition and site-specific glycosylation profiling are emerging as standard methods in the evaluation of Env-based immunogen candidates.

Keywords: HIV, vaccine design, mass spectrometry, glycosylation, envelope, Env, glycomics, glycoproteomics

1. The extensively glycosylated viral spike is the focus of rational vaccine design

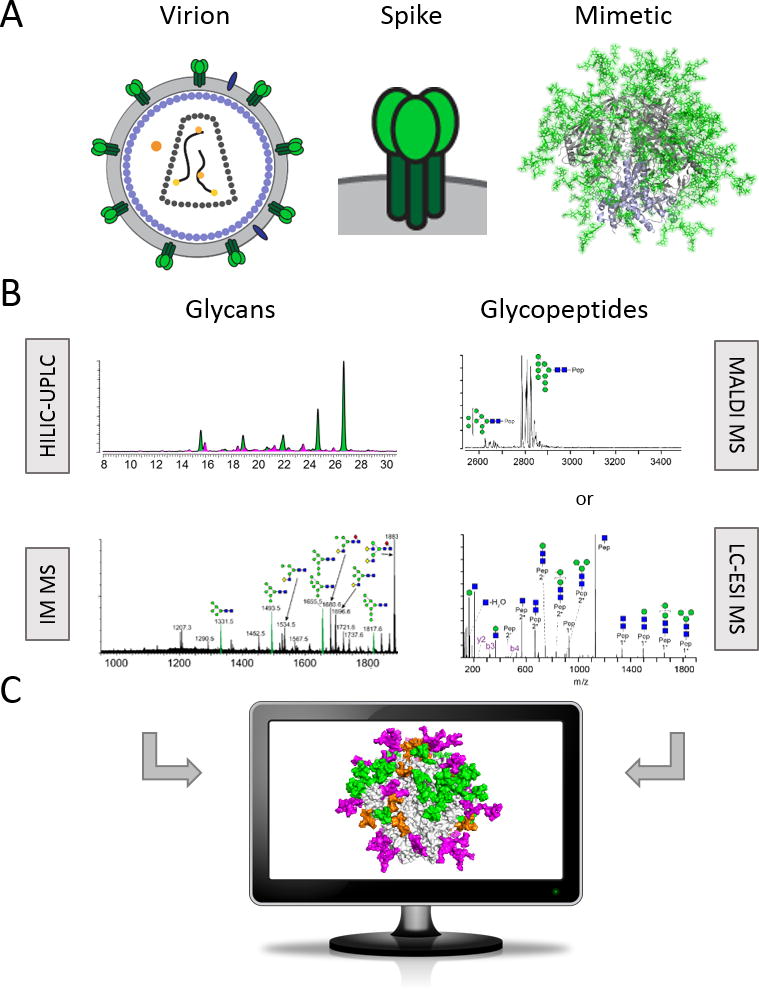

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) remains one of the major health challenges worldwide. While the development of antiretroviral treatments has significantly improved the life of those who have access to medication, an effective vaccine is the desirable solution in controlling the pandemic. The envelope spike (Env) is the sole viral protein on the virion surface and has a crucial role in mediating host cell infection (Figure 1A). Due to its exposed location, it is the main target for HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) elicited by the immune system and thus a main focus for antibody-based vaccine design [1,2]. Over the last years, great progress has been made in designing soluble, recombinant Env-mimicking immunogens that brought us a bit closer to the final aim of the elicitation of bNAbs through vaccination [3].

Figure 1. Methods for HIV Env immunogen glycosylation analysis by glycomics and glycoproteomics.

(A) The trimeric envelope spike is the sole viral protein on the HIV virion surface. Soluble, recombinant, native-like mimics of Env are being developed as immunogens in antibody-based HIV vaccine design. The leading candidate and the basis for further development strategies are trimers of the SOSIP design. On the right is a fully glycosylated model (glycans in green sticks) of the Env mimic BG505 SOSIP.664 based on PDB ID 5ACO [19]. Thorough analysis of the glycans and glycopeptides (B) allows mapping of the site-specific processing state on the trimer surface (C).

Env is a trimer of gp120 and gp41 heterodimers that are generated by proteolytic cleavage (typically by furin) of the pro-protein gp160. It is extensively glycosylated with glycans accounting for a significant proportion of the glycoprotein’s mass [4]. The largely conserved glycans shield the underlying, highly mutative protein surface from the immune system. They further contribute to protein folding, interact with host cell receptors such as DC-SIGN and are indispensable for viral infectivity [5–7]. The majority of Env-targeting bNAbs incorporate glycans into their epitopes [8], which highlights the importance of the glycans to be considered and included in rational immunogen design [9,10]. The particularly dense glycans impose steric constraints on early glycan trimming enzymes i.e. ER and Golgi α-mannosidases that lead to a large abundance of underprocessed, oligomannose-type (Man5‐9GlcNAc2) glycans on the surface of Env [11–17]. These particularly cluster around the outer domain of gp120 and at the trimer interfaces [18,19]. The apex and base of Env generally show more variable processing profiles, with some sites containing a large microheterogeneity of cell type-specific, complex glycans [19]. It is also becoming increasingly evident that Env glycosylation profiles can serve as an indication for native-like protein folding of recombinant Env mimics. Several uncleaved, non-native ‘pseudotrimeric’ Env glycoproteins, for example, show a much higher abundance of complex-type glycans compared to their correctly, uniformly folded counterparts [12,18] (Figure 2). Several different design strategies of soluble, native-like recombinant Env immunogen mimics were recently reviewed by Sanders and Moore [3] and a detailed description is beyond the scope of this review. Of note is that both fully cleaved and uncleaved, linker-based recombinant trimers have been developed that show native-like properties of the viral spike. These linker-based constructs need to be differentiated from the previous generation of uncleaved, sometimes foldon-stabilzed, ‘pseudotrimeric’ gp140 Env constructs [3].

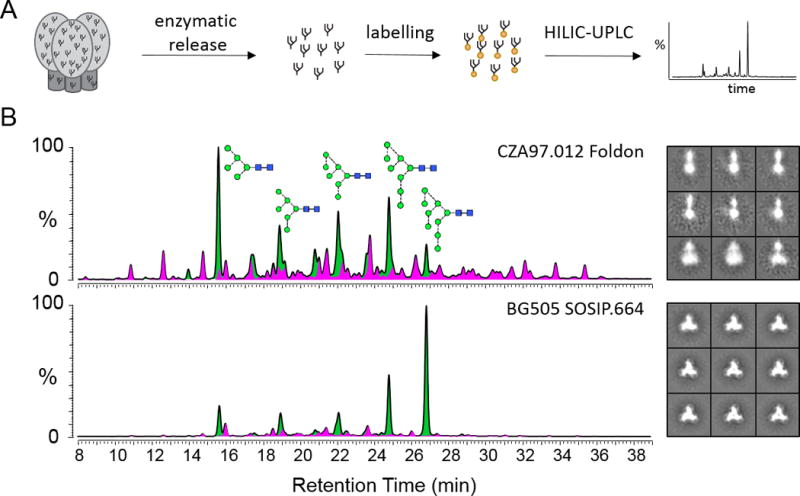

Figure 2. Glycan profiling as a strategy to assess Env immunogen quality.

(A) Glycans are enzymatically released, fluorescently labelled and then quantitatively assessed by HILIC-UPLC. (B) Glycan profiles from two different HIV Env trimer-based immunogens (CZA97.012 Foldon and BG505 SOSIP.664) and the corresponding negative stain electron microscopy images [12]. Green, oligomannose-type and hybrid-type glycans; pink, complex-type glycans, as determined by digestions with Endo H.

While we and others have recently reviewed the viral spike architecture and the structural principles controlling HIV-1 glycosylation in great detail [18,20–22], the following sections focus on the techniques and workflows that facilitate a comprehensive characterization of the Env glycan shield (Figure 1) – a particularly challenging target due to the large number of N-glycosylation sites (around 90 over the trimeric complex). Env glycosylation is shaped by structural constraints around glycosylation sites and it is therefore important to consider immunogen glycosylation when evaluating emerging immunogens [12,23]. We discuss a variety of analytic methods for assessing immunogen glycosylation from accessible chromatographic methods to those requiring sophisticated mass spectrometers.

2. Global profiling of the overall Env glycosylation fingerprint

Quantitative profiling of the overall N-glycosylation pool of candidate immunogen Env mimics can provide a valuable insight into protein quality and preserved native-like features of the glycan shield [12,18]. Envelope glycosylation is characteristically dominated by oligomannose-type glycans. The abundances of oligomannose-type glycans of so far characterized soluble, recombinant, trimeric Env mimics such as e.g. BG505 SOSIP.664, BG505 SOSIP.v4.1, B41 SOSIP.664 and AMC008/11 SOSIP.664 typically range from ~60 % to ~70 % [18,19,24–29]. The most prominent structure is usually the most underprocessed glycan Man9GlcNAc2 with a relative abundancy of ~20 % to ~40 % compared to other glycoforms (Figure 2B).

Accurate quantification of the relative abundancies of individual glycan structures/species on envelope is best achieved by glycan release followed by labelling of the reducing end with a functional tag and chromatographic separation. In general, glycans can be released from the underlying protein through chemical and enzymatic methods. Enzymatic release by peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) is the most common way of releasing mammalian N-linked glycans and allows for subsequent labelling with a fluorophore due to the generation of a reducing glycan end that contains hemiacetal functionality. Fluorophores such as 2-aminobenzoic acid (2-AA) and 2-aminobenzamide (2-AB) stably label glycans in a 1:1 ratio by reductive amination [30] and thus allow quantification via detection of fluorescence [31]. More recently, procainamide emerged as an alternative tag to 2-AA and 2-AB labelling, which has a higher fluorescence quantum yield and is thus more sensitive and improves detection of minor glycan species [32]. Labelled Env glycans can be nicely resolved by (ultra-/) high-performance liquid chromatography (U/HPLC) using, for example, amide-based hydrophilic-interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) and monitored by fluorescence detection (Figure 2A). Noteworthy, HILIC-UPLC has the potential to separate glycan isomers [33–35].

This outlined approach can be combined with endo-exoglycosidase digestions to assign glycan structures and to determine the abundances of oligomannose- and hybrid- vs. complex-type glycans [12]. The relative quantification of oligomannose-type glycans is of considerable interest when analyzing candidate Env immunogens and is emerging as part of their routine quality control. Digestion of the labelled glycan pool with Endoglycosidase H (Endo H) removes oligomannose-type and hybrid-type glycans. Integration of the relevant glycan peak areas in the HILIC-UPLC profiles before and after Endo H digestion allows for the determination of the percentage abundance of the oligomannose-series glycans Man5-9GlcNAc2 [12,36].

Profiling of O-glycosylation can generally be more challenging than N-glycosylation in that there is not a defined amino acid consensus sequence and also the lack of a universal enzyme to remove all O-glycan structures. It is therefore necessary to employ chemical release methods, such as reductive β-elimination or hydrazinolysis. However, the role of O-glycosylation in Env glycobiology is uncertain and currently there is little supporting evidence for a significant functional or structural role [37]. Studies have previously identified O-glycans on recombinant Env at positions T499 and T606 [13,16,38,39], although a quantitative study also showed that T499 on a native-like trimer mimic was less than 1 % occupied with O-glycans [18]. While native viruses are weakly neutralized by anti-Tn and anti-sialosyl-Tn antibodies [40], glycoproteomics studies on these have led to conflicting results as to whether O-glycans are present [39,41]. Overall, the oligomannose-dominated N-glycosylation fingerprint of Env is an intrinsic feature of the protein, whereas the presence of O-glycosylation likely depends on the producer cell of the virus and is thus presumably less important for the evaluation of Env glycoprotein immunogens.

3. Mass spectrometry of released glycans

Mass spectrometry (MS) is the leading method for structural characterization of released Env glycans. The most common ionization technique used is electrospray ionization (ESI), which is often coupled to liquid chromatographic (LC) separation, helping separate isomeric structures prior to MS detection. Ionization of glycans can be influenced by a range of factors, in particular the presence of charged residues, such as sialic acids, which influence the efficiency of ion formation during ESI. Correspondingly, quantification by ESI-MS is not as reliable as HPLC methods as discussed above and should therefore be carefully considered. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) of permethylated glycans has also been used in Env analysis and benefits from the prevalence of singly charged ions that aids in evaluating relative glycan amounts [17,39,42]. Additionally, permethylation overcomes a well-known problem of sialic acid residue loss that occurs on underivatized glycans during MALDI. However, while the presence of sialylated glycans was shown to be important for the recognition of Env by a number of bNAbs [43–45], the overall abundance of sialic acids on recombinant Env mimics is generally rather low [19]. In both ESI and MALDI approaches, collision induced dissociation (CID) of glycan parent ions delivers detailed structural information on the oligosaccharide composition and glycosidic linkages [46]. CID of negative ions yields extensive A-type cross-link fragments which are more informative as compared to less informative B- and C-type fragments across glycosidic bonds which predominate in positive ion analyses (Figure 3). Overall, well-established glycomics workflows based on LC-ESI MS/MS and MALDI MS/MS are principally applicable and provide detailed evaluation of Env glycans.

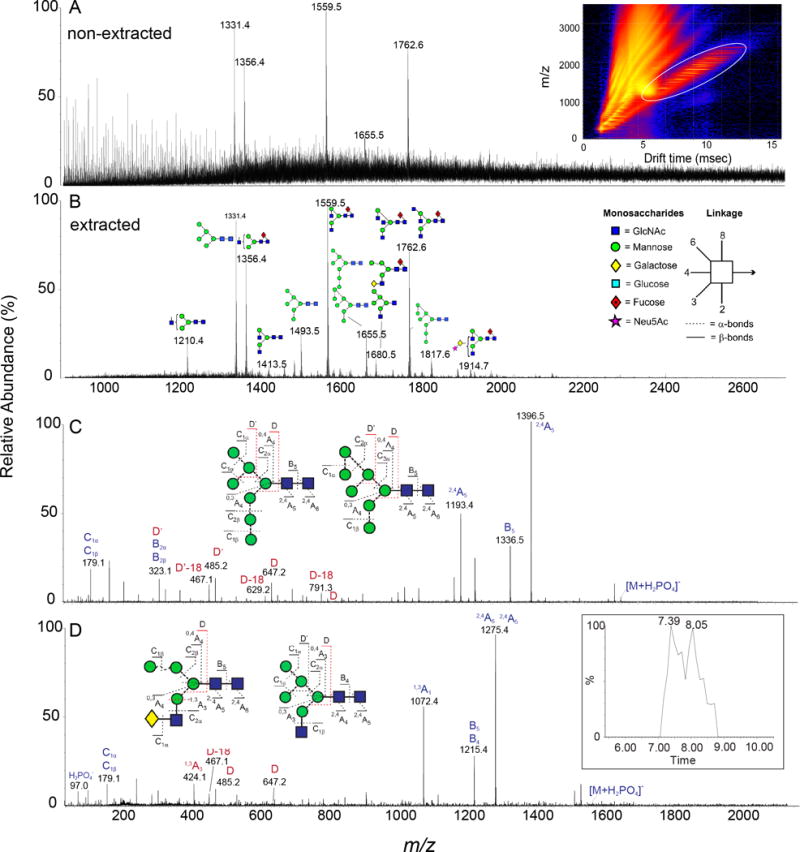

Figure 3. Env glycosylation analysis by ion mobility mass spectrometry.

Spectrum of released glycans from BG505 SOSIP.664 before (A) and after (B) ion mobility extraction. The inset in panel A shows the DriftScope image (m/z against drift time) with singly charged ions encircled with a white oval. (C-D) Collision-induced dissociation spectra for two isobaric structures derived from the transfer region of the Synapt G2Si instrument [19]. The insets in panels C and D show the corresponding glycans as well as the numbering of the fragments. Fragments used to differentiate the two underlying structures are labelled in red. The inset in panel D shows the chromatographic separation of the two structures after ion mobility extraction. Symbols are as explained in (B).

More recently, ion mobility (IM) MS has emerged as a powerful method for structural characterization of released glycans in its ability to rapidly separate oligosaccharide ions and boost sensitivity [47–52] (Figure 3). In IM, gas-phase glycan ions travel through a neutral gas, typically nitrogen or helium, under a weak electric field and are separated based on their size, shape and charge. Glycan ions are usually singly and doubly charged and have distinct three-dimensional structures leading to diverse IM drift times. These drift times can be used to calculate the rotationally averaged collision cross section (CCS), which is an intrinsic property of each individual glycan structure.

In general, the benefit of IM for Env glycan analysis (and equivalent reports of oligomannose type structures) is through the ability to extract N-glycan spectra from non-carbohydrate contaminants in a sample [49,50] and secondly, the capacity to separate isomers thereby improving structural assignments [47,48]. Oligosaccharides IM drift times are unique compared to lipids, peptides and nucleotides [53] and therefore can be isolated and evaluated from complex mixtures (Figure 3A and 3B). In this way, glycan sensitivity is increased addressing a key challenge in glycomics. Additionally, oligomannose Env glycan isomers can effectively be separated by IM in both positive ([M+Na]+) and negative mode ([M+H2PO4]+) [47,48]. In this report, the CCS values were determined in both He and N2 and showed that isomers have characteristic IM drift times, particularly structures with mannose substituted on the 3-arm. For oligomannose glycans, it is important to consider the type of adduct examined as [M-H]− ions adopt noticeable gas-phase anomers and/or conformers, which may be easily misinterpreted as isomers, leading to false positive identifications [54]. Additionally, the ability to predict glycan CCS values is increasing difficult and presently for deprotonated species unattainable making theoretical calculations of gas-phase doubtful [55]. However, IM holds tremendous potential for glycan analysis and already IM has proven advantageous for Env glycan analysis and will continue to gain popularity as instruments develop and separation resolution advances.

4. Site-specific glycosylation analysis

Total glycan profiling is limited in that it does not provide information on the sites of N-glycan attachment. Defining the composition and microheterogeneity of Env glycosylation on individual glycan sites is important for understanding bNAb epitopes, for guiding rational vaccine design and for thorough evaluation of potential Env immunogens. However, site-specific N-glycosylation analysis of Env, which typically requires protease digestion and glycopeptide analysis, can be difficult due to the high number of N-glycosylation sites. Nevertheless, multiple studies have so far been performed on recombinant monomeric Env [13,14,18,23,56–59], uncleaved gp140 [16,18,23,38,60–64], fully cleaved, trimeric Env [18,19,23,65], membrane-associated Env [16,23] and virion-derived gp120 [17,41]. Broadly speaking, glycans of complex or mixed processing states are mainly localized at trimer base and apex in the C1, V1/V2, V4 and gp41 region of the trimer. Oligomannose-type glycans cluster at the outer domain of gp120 and near the trimer interface in the C2, V3 and C3 regions [18,20].

Glycoproteomics studies (analysis of glycopeptides) of Env typically involve reduction, alkylation and protease digestion of the target protein – followed by analysis of the glycopeptides by mass spectrometry. Analytics is challenging because of the glycan micro- and macroheterogeneity and the lower proportion of glycopeptides compared to peptides in protease-digested samples accompanied by ion suppression effects [66]. Hence, multiple strategies have been developed to improve analysis of glycopeptides. Among them are glycopeptide enrichment by lectin affinity chromatography, hydrazide-capture, boronic acid-based chemistry, graphitized carbon, size-exclusion chromatography and HILIC separation [66,67]. While some of these strategies, like lectin affinity chromatography, bind to specific glycan structures, methods based on general chemical and physical properties of glycopeptides are more valuable for unbiased enrichments. An example for a robust, unbiased stationary phase for glycopeptide enrichment is zwitterionic-HILIC (ZIC-HILIC), which leads to the separation of compounds based on weak electrostatic interactions and portioning of the hydrophilic glycopeptides between the zwitterionic phase and the aqueous portion of the mobile phase [66,68]. Similar to the above described glycomics methodologies, glycoproteomics on Env have been performed using both MALDI MS and LC-ESI MS.

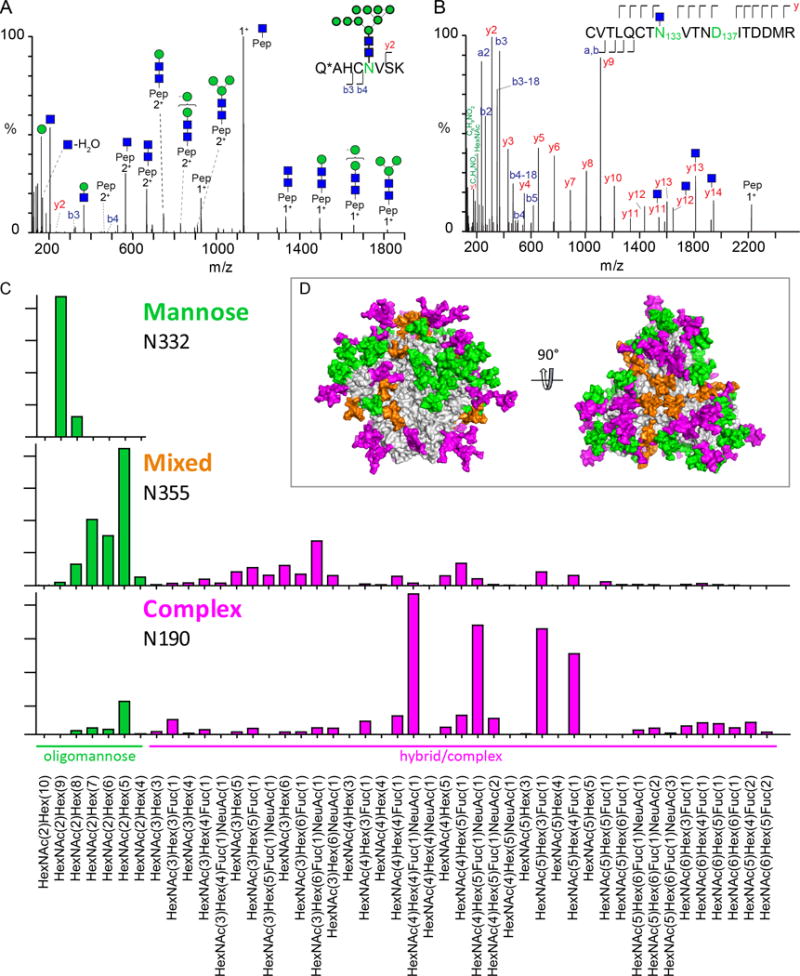

The glycan moiety and the peptide backbone of glycopeptides differ in their chemical properties and thus fragment under different conditions in tandem mass spectrometry. The two main fragmentation types to consider in tandem MS experiments are collision-induced dissociation (CID) and electron-transfer dissociation (ETD). CID predominantly leads to glycosidic bond cleavages of the B- and Y-type (nomenclature by Domon and Costello [69]) and also creates characteristic ‘reporter’ low-molecular-weight oxonium ions (fragment ions originating from the glycan moiety) that can serve as diagnostic ions for glycopeptides [70]. Peptide backbone fragments such as b- and y-type ions are typically of lower abundance but can be increased by the usage of higher collision energies ([71]). Higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD) fragmentation is a beam-type version of CID, where fragmentation occurs external to the ion trap in an ion routing multipole, but leads to quite similar fragmentation ions. Figure 4A shows an HCD fragmentation spectrum of a glycopeptide containing a Man9GlcNAc2 glycosylated Asn332 of Env – the so-called ‘supersite of immune vulnerability’ [72].

Figure 4. Quantitative site-specific N-glycosylation analysis by LC-ESI MS.

(A) HCD fragmentation of a tryptic glycopeptide containing N332 (reproduced from [19]). (B) HCD fragmentation spectrum of a glycopeptide sequentially deglycosylated with Endo H followed by PNGase F. (C) Quantitative site-specific N-glycosylation profiles obtained for an oligomannose (N332), a mixed (N355) and a complex (N190) glycan site of BG505 SOSIP.664 [19]. (D) Model of a fully glycosylated soluble BG505 SOSIP.664 trimer. Glycans are coloured according to their oligomannose content, with 100 % - 80 % green; 79 % to 40 % orange; 39 % - 0 % pink [18,19].

ETD selectively creates peptide bond fragments through the transfer of gas-phase electrons from singly charged anions to multiply charged protonated peptides [67]. Peptide backbone fragments are predominantly c’ ions and z· radical ions resulting from cleavage of the N-Cα bond and thus allow the determination of the peptide backbone as well as the site of glycosylation. Therefore, tandem MS experiments using both CID and ETD can accurately assign the glycan moiety and the peptide backbone of a glycopeptide.

Tandem LC-ESI MS experiments have also been employed to successfully identify the N-glycan(s) on peptides carrying two potential N-glycosylation sites (PNGS). In one example, shown in Figure 4B, the HCD fragmentation spectrum of a doubly occupied Env glycopeptide was sequentially digested with Endo H, followed by PNGase F. The fragmentation ions allowed the determination of the glycan site containing an oligomannose-type glycan (a single GlcNAc after Endo H digestions) and that of a complex-type (or spontaneously deamidated) glycan, identified due to the conversion of asparagine to aspartate by PNGase F.

MALDI MS/MS is another powerful technique for the analysis of glycopeptides that has been employed to analyze Env glycosylation analysis previously [19,56,60]. Unlike electrospray ionization, MALDI solely creates singly charged ions and thus makes spectra interpretation and relative quantitation possible. Fragmentation of N-glycopeptides by MALDI MS/MS leads to a set of cleavages at or near the innermost GlcNAc with all resulting fragment ions retaining the peptide backbone [67]. Among the typically observed fragment ions are a [Mpeptide+H-17]+, [Mpeptide+H]+, the0.2X ion [Mpeptide+83+H]+ and the Y1-ion [Mpeptide+203+H]+, which enable the determination of the mass of the peptide portion due to very characteristic peak patterns [67].

When determining the microheterogeneity of N-glycosylation sites, it is not only important to identify the individual glycoforms but also to gain information on their relative abundance. In a label-free quantification approach, the abundance of individual glycoforms is assessed by the relative abundance of signal intensities in the mass spectrum compared to other glycoforms attached to the same N-glycosylation site on the same proteolytic peptide. This is rationalized by the fact that ionization (protonation) of glycopeptides occurs on the peptide backbone and not on the glycan moiety. Hence, ionization efficiency of glycopeptides depends mostly on the peptide sequence and not on the type of glycans [73]. A multi-institutional study by the HUPO Human Disease Glycomics/Proteome Initiative generally assessed label-free quantification as reliable, especially for neutral glycans [74]. Encouragingly, when compared directly in a side-by-side study using an Env mimic, both MALDI MS and LC-ESI MS yielded highly similar quantitative site-specific analysis results [18]. Figure 4C shows example results from quantitative site-specific analysis obtained by LC-ESI MS analysis of oligomannose, mixed and complex-type glycan sites of the Env mimic BG505 SOSIP.664 [18]. This study used IM MS-generated sample-specific glycan libraries as the basis for the site-specific glycopeptide analysis. Together, about 50 different glycans were present on these three sites, highlighting the remarkable complexity and microheterogeneity of Env glycosylation. When mapped on the surface of Env (Figure 4D) the non-random clustering of oligomannose-type glycans becomes obvious.

An aspect that we did not address here, but that has been addressed in other reviews, is the challenge of glycan and glycopeptide data analysis [75–77]. Steadily improving analytical techniques lead to the need of adequate software in order to fully cope with the generated complex data sets. Noteworthy, there are useful data interpretation software solutions that have been successfully employed for the quantitative site-specific glycosylation characterization of Env immunogens [18,19].

5. Assessment of glycan site occupancy

An important aspect when analyzing the microheterogeneity of glycoproteins, especially also with regard to immunogen design, is the level of occupancy on the individual PNGS. Sample preparation workflows that include glycopeptide enrichment steps do not provide information on occupancy since unoccupied peptides are discarded [19]. As it is difficult to reconcile all aspects of interest into one analytical strategy, the determination of the glycan site occupancy of recombinant Env constructs thus relies on alternative methodologies. Recently, intact mass spectrometry of metabolically engineered gp120 was used to assess global occupancy by measuring the entire glycoprotein [78]. This study showed a very high occupancy level of recombinant gp120 N-glycosylation sites, however, the effect of metabolic engineering on protein occupancy during biosynthesis is unknown. A methodology to assess occupancy on a site-specific level has been developed and applied to various Env strains [79]. Here, protease-generated (glyco)peptides are first treated with Endo H and then digested with PNGase F in O18-water. Conversion of Asn to Asp by PNGase F leads to a mass difference of +3 Da due to the incorporation of O18; spontaneous deamidation shows a mass difference of +1 Da and unoccupied sites show no mass shift. Furthermore, it is important to consider that the degree of glycan site occupancy is likely influenced by the producer cell line and also whether or not a protein is codon-optimized [80].

Encouragingly, both of these studies identified the glycan site occupancy level on recombinant Env to be very high. Cao et al., reported that almost all sites are more than 90 % occupied on soluble Env trimers of 6 different strains [79].

Conclusion

The emergence of mass spectrometric methods for glycopeptide analysis and quantitative UPLC approaches for the assessment of the total glycan pool have proven to be powerful tools in the evaluation of HIV immunogens. It has become apparent that HIV immunogens are particularly susceptible to the scrutiny these methods offer as their glycan status changes significantly when processing is not constrained by native-like architecture. It is believed that the presentation of native-like viral spike will be an important component of any successful vaccine that elicits broadly neutralizing antibodies to conformationally sensitive and glycan-dependent epitopes.

Expert Commentary

The processing of glycans during glycoprotein folding and secretion is highly sensitive to the local steric environment of any individual glycan. In this way, glycosylation analysis can be a powerful tool in assessing the protein for native-like folding. This is particularly valuable in the HIV immunogen design field as there has been extensive debate about the degree to which various oligomeric recombinant glycoproteins mimic the native viral spike. This is an essential design feature as it is believed that a successful vaccine is likely to contain conformationally sensitive and glycan-dependent epitopes.

Significant progress has been made in the triaging of candidate immunogens by cryo-electron microscopy. Ward and colleagues have shown that leading immunogens of the SOSIP format exhibit almost entirely native-like folds which cluster into ordered class averages [22,81]. In contrast, candidates based on uncleaved gp140 structures show minimal native like folds and are dominated by highly disordered oligomeric assemblies (Figure 2B). Glycan analysis by UPLC has proven to complement this structural work by providing a measure of native-like folding by the accurate determination of the percentage of oligomannose-type glycans within the released glycan pool. In addition, the advent of relative quantitative mass spectrometric-based glycoproteomics has extended the quality control parameters to that of the glycan composition at individual glycosylation sites.

Given the role of glycosylation in shaping the epitopes of bNAbs, glycan analysis and glycoproteomics have been a key tool in the understanding of the epitopes. This has led to a revised understanding of the glycan targets and has guided the design of new immunogens. For example, many patients that develop bNAbs have circulating virus missing key glycans. It has been hypothesized that the induction of bNAbs could be achieved by the use of immunogens primers that help expand B-cell linages corresponding to the desired bNAbs [82–86]. Glycosylation analytics have shown that deletion of multiple glycans has minimal effect of neighboring glycans and potentially multiple holes can be incorporated into a single immunogen without adversely affecting the remaining glycan-dependent epitopes [79]. Overall, glycan, glycopeptide and intact glycoprotein analytics have emerged as an indispensable tool in the evaluation of immunogens against HIV-1 and in the understanding of the epitopes of broadly neutralizing antibodies.

Five-year view

The ability to distinguish individual glycan structures (microheterogeneity) and overall peptide site occupancy (macroheterogeneity) remains a key challenge in glycoprotein analysis. Recent advances in mass spectrometry techniques are emerging, capable of delivering these information at low levels of sample material. Particularly, ion-mobility separation has now been demonstrated to be able to reveal the presence of mixed population of N-linked glycan isomers on small peptide backbones [87]. Importantly from the perspective of HIV immunogen design, isomers of oligomannose-type glycans - which are often targeted by bNAbs - have been shown to be resolvable with these methods. We envisage that developments in ion mobility resolution will enable the isomeric discrimination and assignment of larger and more complicated glycopeptides. Additionally, high-resolution mass spectrometry of intact glycoproteins is highly informative in both occupancy and glycan composition which has been demonstrated on a range of complex samples [88–90]. Correspondingly, we also envisage that continued software development will enhance the assignment and quantitation of glycopeptide data, analysis of glycan IM results and interpretation of sophisticated intact MS spectra. However, we believe there will be a continued role for the use of orthogonal methods, namely exoglycosidase digests in the assignment of saccharide identity and glycosidic linkages in most glycomics/glycoproteomics methods. Yet, we envisage that this will become enhanced by the development of miniaturized sample handling and automated technologies. There is also a role for these enzymatically assisted assignments to be complemented by developments in selective chemical modification of glycosidic motifs. The continued development of glycoproteomic and glycomic technologies mean that many problems in HIV immunogen design that are currently inaccessible, such as the analysis of native and clinically-derived virions, will be brought under full experimental scrutiny.

Key issues.

Understanding the complex architecture of the HIV-1 glycan shield has important implications for vaccine design.

Glycomics and glycoproteomics strategies for HIV Env immunogen analysis are now widely accepted as valuable tools to assess protein quality and to understand neutralizing antibody responses.

Misfolded, non-native trimeric HIV-1 immunogens show a higher abundance of complex-type glycans compared to native-like trimer mimics – a feature than can be readily assessed by overall glycan profiling by HILIC-UPLC.

Ion mobility mass spectrometry can provide highly detailed structural glycan information allowing a deep insight into the cell-directed glycosylation profiles of Env immunogens.

Site-specific N-glycan analysis workflows provide valuable information on site microheterogeneity and antibody epitopes, as well as occupancy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. David Harvey, Prof. Dennis Burton, Prof. Ian Wilson FRS, and Prof. Raymond A. Dwek FRS for their support and helpful discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Scripps Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology and Immunogen Discovery (1UM1AI100663) and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) and the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center CAVD grant (Glycan characterization and Outer Domain glycoform design; OPP1084519). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No. 681137.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

A.-J. Behrens is a recipient of a Chris Scanlan Memorial Scholarship from Corpus Christi College. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed

References

- 1.Burton DR, Ahmed R, Barouch DH, et al. A Blueprint for HIV Vaccine Discovery. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(4):396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haynes BF, Mascola JR. The quest for an antibody-based HIV vaccine. Immunol Rev. 2017;275(1):5–10. doi: 10.1111/imr.12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders RW, Moore JP. Native-like Env trimers as a platform for HIV-1 vaccine design. Immunological reviews. 2017;275(1):161–182. doi: 10.1111/imr.12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lasky LA, Groopman JE, Fennie CW, et al. Neutralization of the AIDS retrovirus by antibodies to a recombinant envelope glycoprotein. Science. 1986;233(4760):209–212. doi: 10.1126/science.3014647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer PB, Collin M, Karlsson GB, et al. The alpha-glucosidase inhibitor N-butyldeoxynojirimycin inhibits human immunodeficiency virus entry at the level of post-CD4 binding. Journal of Virology. 1995;69(9):5791–5797. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5791-5797.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassol E, Cassetta L, Rizzi C, Gabuzda D, Alfano M, Poli G. Dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3 grabbing nonintegrin mediates HIV-1 infection of and transmission by M2a-polarized macrophages in vitro. Aids. 2013;27(5):707–716. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cfc82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W, Nie J, Prochnow C, et al. A systematic study of the N-glycosylation sites of HIV-1 envelope protein on infectivity and antibody-mediated neutralization. Retrovirology. 2013;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCoy LE, Burton DR. Identification and specificity of broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV. Immunological reviews. 2017;275(1):11–20. doi: 10.1111/imr.12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scanlan CN, Offer J, Zitzmann N, Dwek RA. Exploiting the defensive sugars of HIV-1 for drug and vaccine design. Nature. 2007;446(7139):1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature05818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crispin M, Doores KJ. Targeting host-derived glycans on enveloped viruses for antibody-based vaccine design. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;11:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonomelli C, Doores KJ, Dunlop DC, et al. The glycan shield of HIV is predominantly oligomannose independently of production system or viral clade. PloS one. 2011;6(8):e23521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.Pritchard LK, Vasiljevic S, Ozorowski G et al. Structural constraints determine the glycosylation of HIV-1 envelope trimers. Cell Reports. 2015;11(10):1604–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.017. Pritchard et al. Cell reports, 2015 First study to show that structural constraints control the glycosylation of candidate immunogens. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Go EP, Liao H-X, Alam SM, Hua D, Haynes BF, Desaire H. Characterization of host-cell line specific glycosylation profiles of early transmitted/founder HIV-1 gp120 envelope proteins. Journal of Proteome Research. 2013;12(3):1223–1234. doi: 10.1021/pr300870t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.Leonard CK, Spellman MW, Riddle L, Harris RJ, Thomas JN, Gregory TJ. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265(18):10373–10382. Leonard et al. 1990 J. Biol. Chem. First study analysing the site-specific N-glycosylation of gp120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doores KJ, Bonomelli C, Harvey DJ, et al. Envelope glycans of immunodeficiency virions are almost entirely oligomannose antigens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2010;107(31):13800–13805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006498107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Go EP, Herschhorn A, Gu C, et al. Comparative analysis of the glycosylation profiles of membrane-anchored HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimers and soluble gp140. Journal of Virology. 2015;89(16):8245–8257. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00628-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17**.Panico M, Bouche L, Binet D. Mapping the complete glycoproteome of virion-derived HIV-1 gp120 provides insights into broadly neutralizing antibody binding. Scientific reports. 2016;6:32956. doi: 10.1038/srep32956. Panico et al. 2016, Sci. Rep. A study of the site-specific N-glycosylation of virion-derived gp120 by mass spectrometry showing the dominance of oligomannose-type glycans on almost all N-glycosylation sites. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behrens AJ, Harvey DJ, Milne E, et al. Molecular architecture of the cleavage-dependent mannose patch on a soluble HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimer. Journal of Virology. 2017;91(2):e01894–01816. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01894-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19**.Behrens A-J, Vasiljevic S, Pritchard LK, et al. Composition and antigenic effects of individual glycan sites of a trimeric HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Cell Reports. 2016;14(11):2695–2706. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.058. Behrens et al. 2016 Cell Rep. A quantitative and detailed site-specific study of an Env mimic that employs an ion mobility generated glycan library for subsequent analysis by MALDI MS and LC-ESI MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behrens AJ, Seabright GE, Crispin M. In: Targeting glycans of HIV Envelope glycoproteins for vaccine design. Tan Z, Wang L-X, editors. Royal Society of Chemistry; UK: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behrens AJ, Crispin M. Structural principles controlling HIV envelope glycosylation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;44:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward AB, Wilson IA. The HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein structure: nailing down a moving target. Immunological reviews. 2017;275(1):21–32. doi: 10.1111/imr.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23*.Go EP, Ding H, Zhang S, et al. A glycosylation benchmark profile for HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein production based on eleven Env trimers. Journal of Virology. 2017 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02428-16. Go et al. J. Virol, 2017 An extensive study supporting the conclusion that the processing of many glycosylation sites on recombinant Envs are not affected by the expression system of construct design. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Gils MJ, van den Kerkhof TL, Ozorowski G, et al. An HIV-1 antibody from an elite neutralizer implicates the fusion peptide as a site of vulnerability. Nature microbiology. 2016;2:16199. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Taeye SW, Ozorowski G, Torrents de la Pena A, et al. Immunogenicity of stabilized HIV-1 envelope trimers with reduced exposure of non-neutralizing epitopes. Cell. 2015;163(7):1702–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sliepen K, van Montfort T, Ozorowski G, et al. Engineering and Characterization of a Fluorescent Native-Like HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein Trimer. Biomolecules. 2015;5(4):2919–2934. doi: 10.3390/biom5042919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart-Jones GB, Soto C, Lemmin T, et al. Trimeric HIV-1-Env Structures Define Glycan Shields from Clades A, B, and G. Cell. 2016;165(4):813–826. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medina-Ramírez M, Garces F, Escolano A, et al. Design and crystal structure of a native-like HIV-1 envelope trimer that engages multiple broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1084/jem.20161160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torrents de la Pena A, Julien JP, de Taeye SW, et al. Improving the Immunogenicity of Native-like HIV-1 Envelope Trimers by Hyperstabilization. Cell Rep. 2017;20(8):1805–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bigge JC, Patel TP, Bruce JA, Goulding PN, Charles SM, Parekh RB. Nonselective and efficient fluorescent labeling of glycans using 2-amino benzamide and anthranilic acid. Analytical biochemistry. 1995;230(2):229–238. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anumula KR, Dhume ST. High resolution and high sensitivity methods for oligosaccharide mapping and characterization by normal phase high performance liquid chromatography following derivatization with highly fluorescent anthranilic acid. Glycobiology. 1998;8(7):685–694. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.7.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozak RP, Tortosa CB, Fernandes DL, Spencer DI. Comparison of procainamide and 2-aminobenzamide labeling for profiling and identification of glycans by liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection coupled to electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2015;486:38–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahn J, Bones J, Yu YQ, Rudd PM, Gilar M. Separation of 2-aminobenzamide labeled glycans using hydrophilic interaction chromatography columns packed with 1.7 microm sorbent. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2010;878(3-4):403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takegawa Y, Deguchi K, Ito H, Keira T, Nakagawa H, Nishimura S. Simple separation of isomeric sialylated N-glycopeptides by a zwitterionic type of hydrophilic interaction chromatography. J Sep Sci. 2006;29(16):2533–2540. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200600133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruhaak LR, Zauner G, Huhn C, Bruggink C, Deelder AM, Wuhrer M. Glycan labeling strategies and their use in identification and quantification. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry. 2010;397(8):3457–3481. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3532-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pritchard LK, Spencer DI, Royle L, et al. Glycan clustering stabilizes the mannose patch of HIV-1 and preserves vulnerability to broadly neutralizing antibodies. Nature Communications. 2015;6:7479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Termini JM, Church ES, Silver ZA, Haslam SM, Dell A, Desrosiers RC. HIV and SIV Maintain High Levels of Infectivity in the Complete Absence of Mucin Type O-Glycosylation. J Virol. 2017 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01228-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Go EP, Hua D, Desaire H. Glycosylation and disulfide bond analysis of transiently and stably expressed clade C HIV-1 gp140 trimers in 293T cells identifies disulfide heterogeneity present in both proteins and differences in O-linked glycosylation. Journal of Proteome Research. 2014;13(9):4012–4027. doi: 10.1021/pr5003643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stansell E, Panico M, Canis K, et al. Gp120 on HIV-1 virions lacks O-linked carbohydrate. PloS one. 2015;10(4):e0124784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansen JE, Jansson B, Gram GJ, Clausen H, Nielsen JO, Olofsson S. Sensitivity of HIV-1 to neutralization by antibodies against O-linked carbohydrate epitopes despite deletion of O-glycosylation signals in the V3 loop. Archives of virology. 1996;141(2):291–300. doi: 10.1007/BF01718400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang W, Shah P, Toghi Eshghi S, et al. Glycoform analysis of recombinant and human immunodeficiency virus envelope protein gp120 via higher energy collisional dissociation and spectral-aligning strategy. Analytical chemistry. 2014;86(14):6959–6967. doi: 10.1021/ac500876p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stansell E, Canis K, Haslam SM, Dell A, Desrosiers RC. Simian immunodeficiency virus from the sooty mangabey and rhesus macaque is modified with O-linked carbohydrate. Journal of Virology. 2011;85(1):582–595. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01871-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amin MN, McLellan JS, Huang W, et al. Synthetic glycopeptides reveal the glycan specificity of HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature Chemical Biology. 2013;9(8):521–526. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pancera M, Shahzad-Ul-Hussan S, Doria-Rose NA, et al. Structural basis for diverse N-glycan recognition by HIV-1-neutralizing V1-V2-directed antibody PG16. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2013;20(7):804–813. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Falkowska E, Le KM, Ramos A, et al. Broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies define a glycan-dependent epitope on the prefusion conformation of gp41 on cleaved envelope trimers. Immunity. 2014;40(5):657–668. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harvey DJ. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry of carbohydrates. Mass spectrometry reviews. 1999;18(6):349–450. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2787(1999)18:6<349::AID-MAS1>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harvey DJ, Scarff CA, Edgeworth M, et al. Travelling-wave ion mobility mass spectrometry and negative ion fragmentation of hybrid and complex N-glycans. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jms.3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harvey DJ, Scarff CA, Edgeworth M, et al. Travelling-wave ion mobility and negative ion fragmentation of high-mannose N-glycans. Journal of mass spectrometry. 2016;51(3):219–235. doi: 10.1002/jms.3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harvey DJ, Sobott F, Crispin M, et al. Ion mobility mass spectrometry for extracting spectra of N-glycans directly from incubation mixtures following glycan release: application to glycans from engineered glycoforms of intact, folded HIV gp120. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2011;22(3):568–581. doi: 10.1007/s13361-010-0053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pritchard LK, Harvey DJ, Bonomelli C, Crispin M, Doores KJ. Cell- and protein-directed glycosylation of native cleaved HIV-1 envelope. Journal of Virology. 2015;89(17):8932–8944. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01190-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harvey DJ, Crispin M, Bonomelli C, Scrivens JH. Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry for Ion Recovery and Clean-Up of MS and MS/MS Spectra Obtained from Low Abundance Viral Samples. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;26(10):1754–1767. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1163-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bitto D, Harvey DJ, Halldorsson S, et al. Determination of N-linked Glycosylation in Viral Glycoproteins by Negative Ion Mass Spectrometry and Ion Mobility. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1331:93–121. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2874-3_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fenn LS, Kliman M, Mahsut A, Zhao SR, McLean JA. Characterizing ion mobility-mass spectrometry conformation space for the analysis of complex biological samples. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;394(1):235–244. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2666-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Struwe WB, Benesch JL, Harvey DJ, Pagel K. Collision cross sections of high-mannose N-glycans in commonly observed adduct states - identification of gas-phase conformers unique to [M - H]− ions. The Analyst. 2015;140(20):6799–6803. doi: 10.1039/c5an01092f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Struwe WB, Baldauf C, Hofmann J, Rudd PM, Pagel K. Ion mobility separation of deprotonated oligosaccharide isomers - evidence for gas-phase charge migration. Chemical communications (Cambridge, England) 2016;52(83):12353–12356. doi: 10.1039/c6cc06247d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu X, Borchers C, Bienstock RJ, Tomer KB. Mass spectrometric characterization of the glycosylation pattern of HIV-gp120 expressed in CHO cells. Biochemistry. 2000;39(37):11194–11204. doi: 10.1021/bi000432m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cutalo JM, Deterding LJ, Tomer KB. Characterization of glycopeptides from HIV-I(SF2) gp120 by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2004;15(11):1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pritchard LK, Spencer DI, Royle L, et al. Glycan microheterogeneity at the PGT135 antibody recognition site on HIV-1 gp120 reveals a molecular mechanism for neutralization resistance. Journal of Virology. 2015;89(13):6952–6959. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00230-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Z, Lorin C, Koutsoukos M, et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Reference Standard Lots of HIV-1 Subtype C Gp120 Proteins for Clinical Trials in Southern African Regions. Vaccines. 2016;4(2) doi: 10.3390/vaccines4020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Irungu J, Go EP, Zhang Y, et al. Comparison of HPLC/ESI-FTICR MS versus MALDI-TOF/TOF MS for glycopeptide analysis of a highly glycosylated HIV envelope glycoprotein. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2008;19(8):1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Go EP, Irungu J, Zhang Y, et al. Glycosylation site-specific analysis of HIV envelope proteins (JR-FL and CON-S) reveals major differences in glycosylation site occupancy, glycoform profiles, and antigenic epitopes’ accessibility. Journal of proteome research. 2008;7(4):1660–1674. doi: 10.1021/pr7006957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Go EP, Chang Q, Liao H-X, et al. Glycosylation site-specific analysis of clade C HIV-1 envelope proteins. Journal of proteome research. 2009;8(9):4231–4242. doi: 10.1021/pr9002728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Go EP, Hewawasam G, Liao H-X, et al. Characterization of glycosylation profiles of HIV-1 transmitted/founder envelopes by mass spectrometry. Journal of Virology. 2011;85(16):8270–8284. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05053-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64*.Pabst M, Chang M, Stadlmann J, Altmann F. Glycan profiles of the 27 N-glycosylation sites of the HIV envelope protein CN54gp140. Biological Chemistry. 2012;393(8):719–730. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0148. Pabst et al. Biol. Che, 2012 Comprehensive mass spectrometric analysis of the site-specific glycosylation of gp120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guttman M, Garcia NK, Cupo A, et al. CD4-induced activation in a soluble HIV-1 Env trimer. Structure (London, England : 1993) 2014;22(7):974–984. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ongay S, Boichenko A, Govorukhina N, Bischoff R. Glycopeptide enrichment and separation for protein glycosylation analysis. J Sep Sci. 2012;35(18):2341–2372. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201200434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wuhrer M, Catalina MI, Deelder AM, Hokke CH. Glycoproteomics based on tandem mass spectrometry of glycopeptides. Journal of chromatography. B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences. 2007;849(1-2):115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Di Palma S, Boersema PJ, Heck AJR, Mohammed S. Zwitterionic hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (ZIC-HILIC and ZIC-cHILIC) provide high resolution separation and increase sensitivity in proteome analysis. Analytical chemistry. 2011;83(9):3440–3447. doi: 10.1021/ac103312e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Domon B, Costello CE. A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugates. Glycoconjugate Journal. 1988;5(4):397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mechref Y. Use of CID/ETD mass spectrometry to analyze glycopeptides. Current protocols in protein science. 2012:11–11. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps1211s68. Chapter 12, Unit 12(11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cao L, Tolic N, Qu Y, et al. Characterization of intact N- and O-linked glycopeptides using higher energy collisional dissociation. Analytical Biochemistry. 2014;452:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kong L, Lee JH, Doores KJ, et al. Supersite of immune vulnerability on the glycosylated face of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2013;20(7):796–803. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wada Y. Glycan profiling: label-free analysis of glycoproteins. Methods in molecular biology. 2013;951:245–253. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-146-2_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wada Y, Azadi P, Costello CE, et al. Comparison of the methods for profiling glycoprotein glycans–HUPO Human Disease Glycomics/Proteome Initiative multi-institutional study. Glycobiology. 2007;17(4):411–422. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walsh I, Zhao S, Campbell M, Taron CH, Rudd PM. Quantitative profiling of glycans and glycopeptides: an informatics’ perspective. Current opinion in structural biology. 2016;40:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Woodin CL, Maxon M, Desaire H. Software for automated interpretation of mass spectrometry data from glycans and glycopeptides. The Analyst. 2013;138(10):2793–2803. doi: 10.1039/c2an36042j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dallas DC, Martin WF, Hua S, German JB. Automated glycopeptide analysis–review of current state and future directions. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2013;14(3):361–374. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Struwe WB, Stuckmann A, Behrens A-J, Pagel K, Crispin M. Global N-glycan site occupancy of HIV-1 gp120 by metabolic engineering and high-resolution intact mass spectrometry. ACS chemical biology. 2017;12(2):357–361. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79**.Cao L, Diedrich JK, Kulp DW, et al. Global site-specific N-glycosylation analysis of HIV envelope glycoprotein. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14954. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14954. Cao et al. 2017, Nat. Comm. This study presents a workflow using sequential glycosidase digestion and H2O18-labelling for the site-specific characterization of Env immunogens into complex-/mannose- or hybrid or unoccupied N-glycosylation sites. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Honarmand Ebrahimi K, West GM, Flefil R. Mass spectrometry approach and ELISA reveal the effect of codon optimization on N-linked glycosylation of HIV-1 gp120. Journal of Proteome Research. 2014;13(12):5801–5811. doi: 10.1021/pr500740n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee JH, Ozorowski G, Ward AB. Cryo-EM structure of a native, fully glycosylated, cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2016;351(6277):1043–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bonsignori M, Zhou T, Sheng Z, et al. Maturation Pathway from Germline to Broad HIV-1 Neutralizer of a CD4-Mimic Antibody. Cell. 2016;165(2):449–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haynes BF, Kelsoe G, Harrison SC, Kepler TB. B-cell-lineage immunogen design in vaccine development with HIV-1 as a case study. Nature biotechnology. 2012;30(5):423–433. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malherbe DC, Doria-Rose NA, Misher L, et al. Sequential immunization with a subtype B HIV-1 envelope quasispecies partially mimics the in vivo development of neutralizing antibodies. Journal of Virology. 2011;85(11):5262–5274. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02419-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ota T, Doyle-Cooper C, Cooper AB, et al. Anti-HIV B Cell lines as candidate vaccine biosensors. Journal of immunology. 2012;189(10):4816–4824. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Medina-Ramirez M, Garces F, Escolano A, et al. Design and crystal structure of a native-like HIV-1 envelope trimer that engages multiple broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in vivo. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1084/jem.20161160. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Glaskin RS, Khatri K, Wang Q, Zaia J, Costello CE. Construction of a Database of Collision Cross Section Values for Glycopeptides, Glycans, and Peptides Determined by IM-MS. Anal Chem. 2017;89(8):4452–4460. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang Y, Liu F, Franc V, Halim LA, Schellekens H, Heck AJ. Hybrid mass spectrometry approaches in glycoprotein analysis and their usage in scoring biosimilarity. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13397. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang Y, Barendregt A, Kamerling JP, Heck AJ. Analyzing protein micro-heterogeneity in chicken ovalbumin by high-resolution native mass spectrometry exposes qualitatively and semi-quantitatively 59 proteoforms. Anal Chem. 2013;85(24):12037–12045. doi: 10.1021/ac403057y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leney AC, Rafie K, Van Aalten DMF, Heck AJR. Direct monitoring of protein O-GlcNAcylation by high-resolution native mass spectrometry. ACS Chem Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]